CHAPTER 16

Sistine Chapel installations

An obvious objection to the idea that The Last Judgement was planned to function as part of a spectacle that took place only a few times during the Holy Week is that it had to be kept in place year round. A brief look at the activities in the Sistine Chapel over the liturgical year is therefore of interest. The Renaissance chapel was by no means only a place for quiet contemplation. Visiting preachers were at times disrupted or laughed at, and the congregation could be so loud and talkative that the sermons could hardly be heard: ‘This phenomena of noise and other misbehaviour in the chapel reveals’ that ‘despite an ideal of order and elegance … these were in many ways still turbulent days, even ceremonially.’401 The style of preaching was in itself ambiguous. Aiming for both pleasurable form and sound, it had a close affinity to poetry and at times also incorporated singing.402 Besides the special ceremonies for the installation of new Popes and Cardinals (and their funerals) about forty congregations were held in the chapel each year.403 Normally Mass was celebrated, but also Vespers and Matins, while more exclusive occasions would call for especially elaborate arrangements. Many of the more important feasts brought larger congregations and took place outside the Sistine Chapel, though. The celebrations for the Virgin were often held in Santa Maria Maggiore and those of St John in St John Lateran, Advent was largely celebrated in Cappella Paolina, and Christmas always in St Peter’s. When Mass was celebrated in the Sistine, it was still not obligatory for the Pope to be present; on some occasions, such as the Feast of the Circumcision, the Master of Ceremonies officiated instead. It is noteworthy that even in the eighteenth century there was no specific music for such services.404 When the Pope was present, on the other hand, Mass was usually complemented with the singing of motets, a musical genre distinct from more ‘genuinely liturgical works’ and one that gave an artistic touch to the ritual—but that seems not to have been much appreciated by the Masters of Ceremonies.405

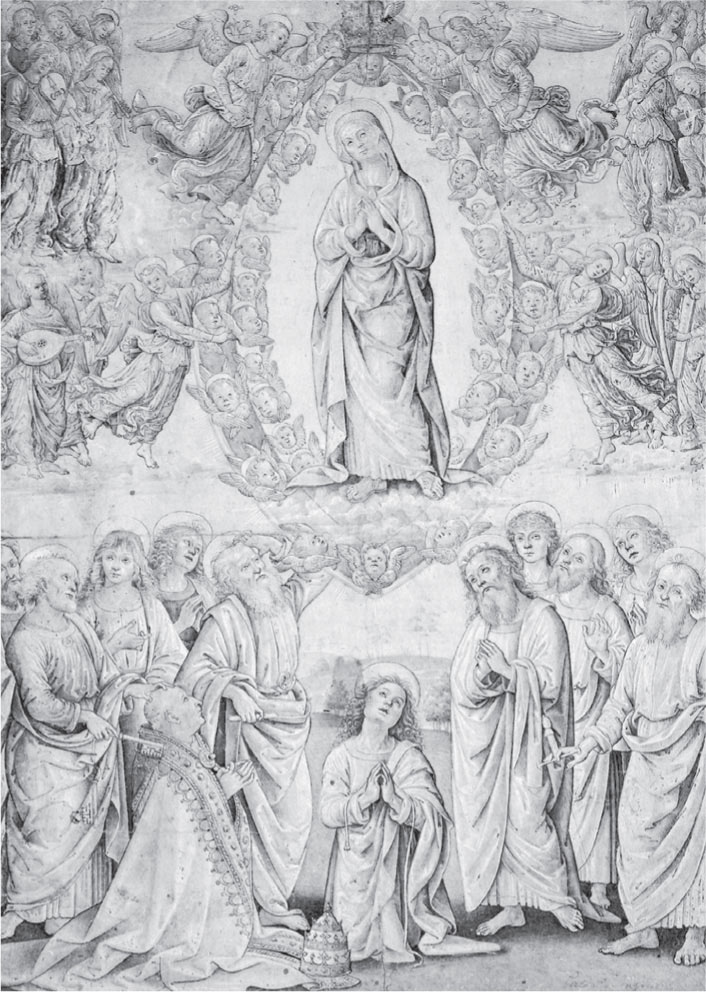

Fig. 16.1 a. Unknown artist after Perugino, Assumption of the Virgin, c.1480. Albertina, Vienna. Pen drawing. (Photo: Albertina)

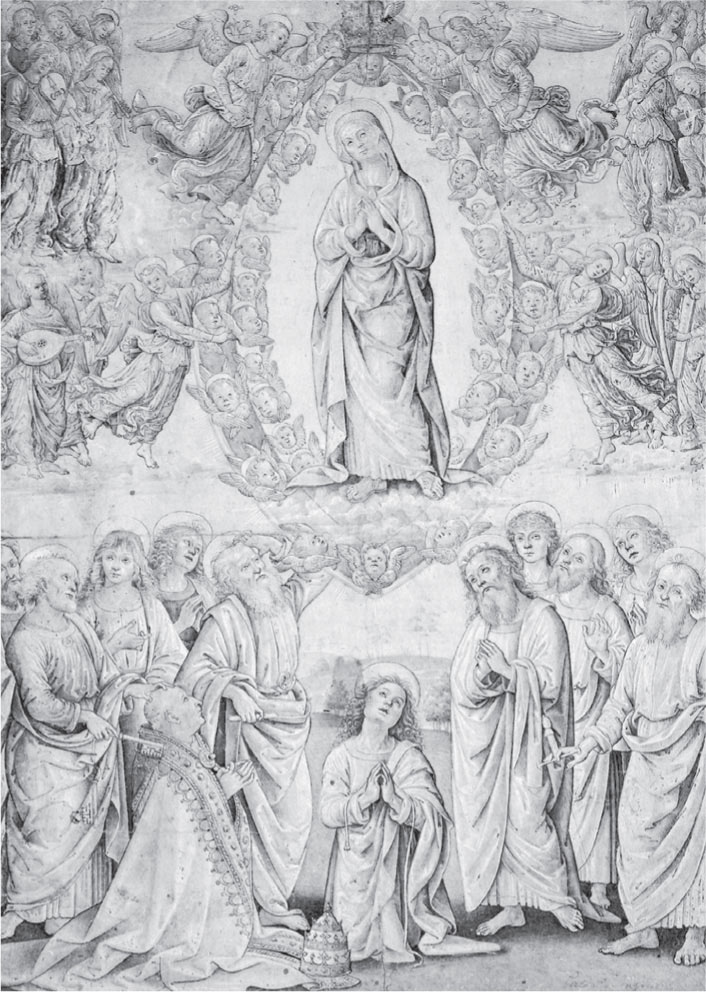

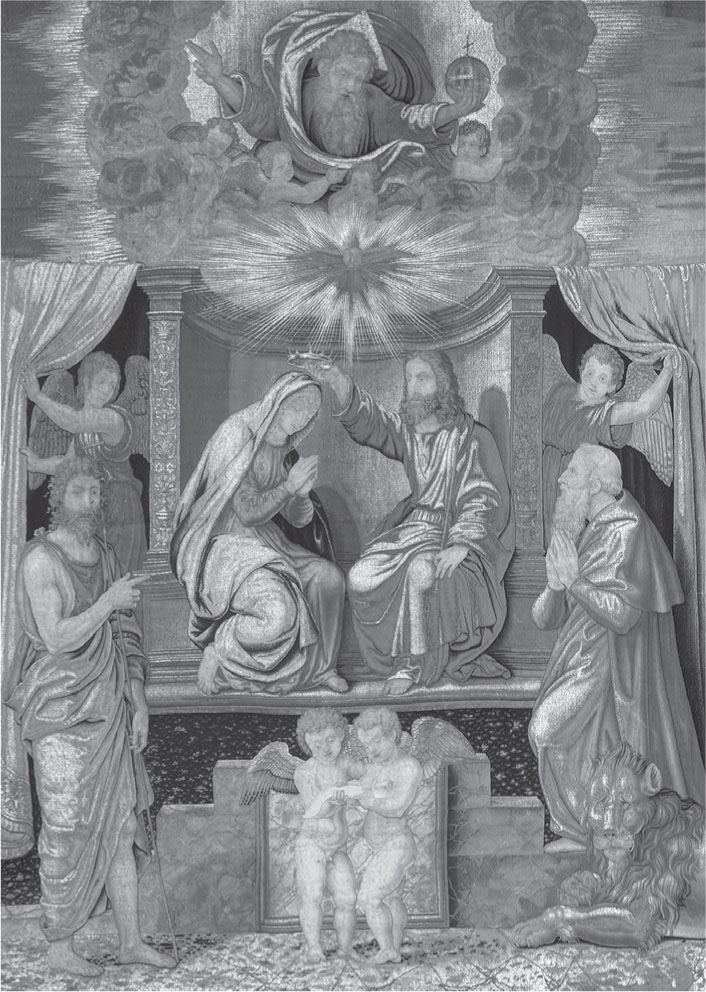

Fig. 16.1 b. School of Raphael, Coronation of the Virgin, c.1540. Vatican Museums, Rome. Tapestry. (Photo: Vatican Museums)

The most important feast celebrated by the Pope in the Sistine Chapel was without doubt Easter, from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. This was also the only time of year when the whole of The Last Judgement was visible. On Good Friday, in order to underline the severe character of proceedings, the chapel was kept ‘tota nuda, sedes nudae, altare nudum’, and as the Master of Ceremonies noted as early as the 1480s, during Tenebrae ‘nuda fuit tota capella pape’.406 For this ceremony only, the chapel was bereft of its fine tapestries and altar decorations—normally, as most of the illustrations of the Chapel from the sixteenth century onwards show, there was a baldachin above the altar, covering the scene with the grotto (Fig. 5.2).

In the early sixteenth century, the altar was decorated with a painting by Perugino of The Assumption of the Virgin. A small drawing survives that is believed to reproduce this painting accurately (Fig. 16.1 a).407 Assuming the proportions to be correct, it is possible to make an informed guess as to its position on the altar. With its border it would have been about 3.4 metres by 2.6 metres wide.408 After the painting was destroyed when work on Michelangelo’s fresco began, it seems that it was replaced by a tapestry of the Raphael School—still in the Vatican collection—of The Coronation of the Virgin (Fig. 16.1 b).409 In iconography and composition it is very close to a drawing by Raphael now in Oxford. The tapestry was only slightly larger than the original altarpiece, 3.55 metres by 2.93 metres wide. On special occasions, it was possible to hang very different tapestries on the altar. For example, Stendhal, who visited the chapel several times, noted that at one point there was a tapestry after Federico Barocci’s painting of The Annunciation above the altar.410 In the mid seventeenth century a series of tapestries were produced for the altar after cartoons by Carlo Maratta’s workshop.411

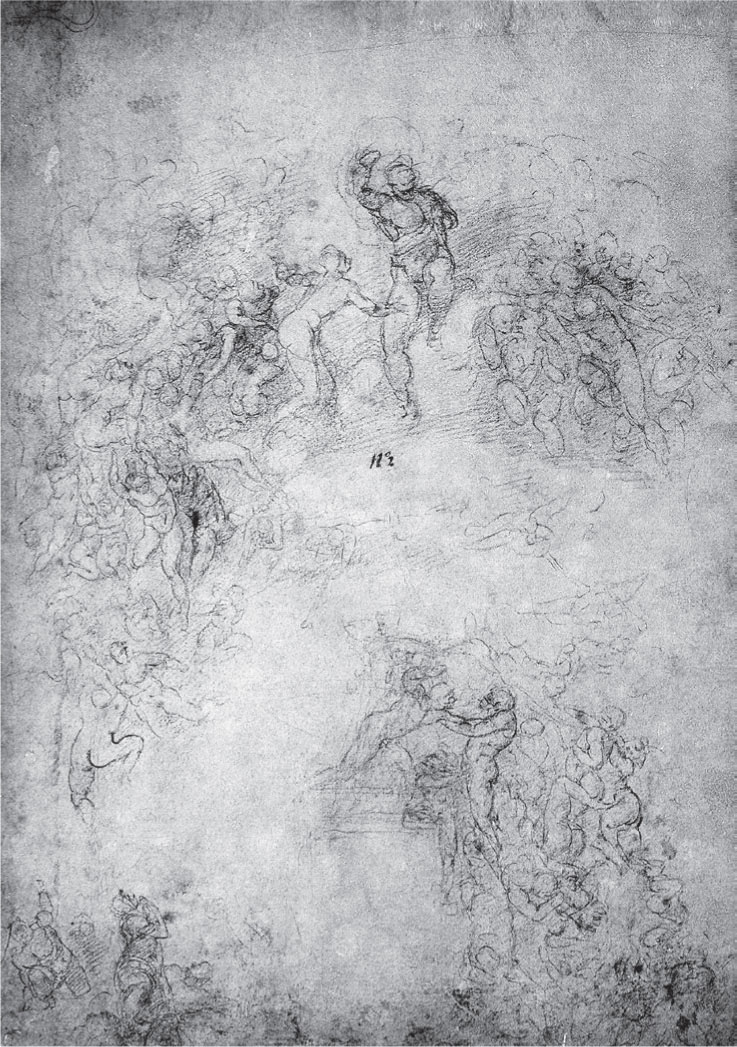

There is a drawing by Michelangelo in Casa Buonarroti in Florence that should be mentioned here (Fig. 16.3). It is one of the few preparatory drawings that have survived. As an early sketch for the lower part of the composition, it has at times puzzled scholars because it seems to show the presumably destroyed painting by Perugino on the altar.412 Interestingly, Michelangelo’s figures adjust perfectly to its framework, subordinating and relating their gestures and gazes to its presence. It would be wrong to assume that Perugino’s altarpiece was still in place, however; Michelangelo’s figures, more likely, relate to the general presence of a baldachin over the altar, just like the one usually there—even though the motifs might vary according to the Church calendar. Even in the final version, there is a clear horizontal structure to the composition, so that the tapestry could be put in place without disturbing the scene or cutting figures in half. The altar setting would cover the little grotto and an otherwise peculiarly empty part of the fresco. Above it would be seen the trumpeting angels, heralding the Madonna, the Child, or whichever saint was currently on display on the altar. The drawing shows that Michelangelo did consider the fact that his fresco would be covered by other works of art on occasion, and that he responded creatively to that premise.

During the more important celebrations, the chapel was usually hung with the famous Raphael tapestries, produced in Brussels from the cartoons he made in 1515–16. The display of the tapestries in the chapel has been reconstructed and debated by several scholars, most authoritatively by John Shearman.413 However, there is a problem with these reconstructions—besides the severe ‘tone of certitude’ that often distinguishes them—in that they presuppose that all of Raphael’s tapestries were necessarily hung in the chapel at the same time (or perhaps at all times).414 The catch is that there is every likelihood that there were more than the ten Raphael tapestries we have today—a contemporary witness who saw them in the workshop in Brussels speaks of sixteen.415

Fig. 16.2 a. Pieter van Aelst after Raphael, Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1515–1516. Vatican Museums, Rome. Tapestry. (Photo: Getty Images)

Fig. 16.2 b. Pieter van Aelst after Raphael, Conversion of Saint Paul, 1515–1516. Vatican Museums, Rome. Tapestry. (Photo: Vatican Museums)

Furthermore, the Vatican had plenty of other tapestries, used on many different occasions and not only in the Sistine Chapel. An inventory of 1518 mentions forty-seven tapestries acquired by Leo X to be used in the chapel.416 For the ten surviving Raphael tapestries to fit, one has to assume that they were hung on both sides of the chancel screen. An ocular inspection of the walls shows that there are plenty of hooks and the like suitable for this purpose on the principle side of the screen, where the pope and cardinals would have been seated, but none at all on the other side of the screen. Moreover, even if hung on both sides, the ten tapestries would not fill the available space particularly well. The obvious conclusion seems to be that the Raphael tapestries known today were not meant to hang together in a certain order or programme in the Sistine Chapel, and probably they were not all meant to be there at the same time. This means that there is little possibility of knowing precisely how the chapel was decorated at different stages of the liturgical year, or how that changed over its history. There seems to have been room for both variation and improvisation. That said, it is still possible to learn more about the altar wall, which is of central importance in the present context.

According to Shearman, Raphael’s tapestry The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, in which St Peter featured prominently, was originally placed to the right of the altar (Fig. 16.2 a). This seems reasonable, not only because of its dimensions, but because of the tradition of placing St Peter and St Paul closest to the altar. Shearman suggests the tapestry of The Stoning of St Stephen was on the left of the altar, his solution to the problem of fitting this somewhat oddly sized tapestry (4.50 by 3.70 metres) on the walls next to the larger ones. More likely, it was used at the altar during the feast of St Stephen, one of the more important feasts celebrated in the chapel. A more probable candidate for the left-hand side of the altar is The Conversion of St Paul (Fig. 16.2 b). This would correspond better both in size and iconography with the St Peter tapestry.417 The tapestries together would have covered the lower part of the fresco, the tapestry with St Paul being 5.30 metres wide, The Coronation 2.93, and the one with St Peter 5.12, or 13.35 metres in all, neatly corresponding with the 13.4 metres of the wall. The tapestries to the sides are both 4.92 metres high, while the tapestry above the altar is much lower, only 3.55 metres, leaving space for the full 1.3 metres of the altar, making a total 4.85 metres.418 What can be said for certain, then, is that when the Pope celebrated Mass in the Sistine Chapel, the walls and the altar would have been decorated with tapestries with suitable motifs. Above the altar, covering the lower part of The Last Judgement, there was often a tapestry representing the The Coronation of the Virgin, and to the sides there was space for Raphael’s tapestries of St Peter and St Paul (Fig. 16.2). These tapestries would already have been available to hang there when Michelangelo began work on the altar wall.419

Interestingly, it seems there was an initiative in the late sixteenth century to commission new tapestries to be hung during Easter, since the ones by Raphael were considered too splendid and best fit for ‘tempi allegri’.420 This plan was never realized, and instead an extraordinary collection of vestments was produced in the 1590s for the occasion, which survive to this day in the Vatican, and were probably those mentioned by Wennerberg as ‘splendid’.421 They were designed by Allessandro Allori as a gift from Ferdinand I de’ Medici to Clement VIII, specifically to be used during Easter celebrations in the Sistine Chapel. The vestments had pictorial embroideries that included the Passion, the Sacrifice of Abraham, and Lazarus. An altar frontal was also produced, so that below the grotto of Michelangelo’s fresco one would have seen the dead Christ in the tomb, accompanied by two angels, and at the sides of the altar Christ in Limbo and Christ appearing to the Madonna (Fig. 16.2). Allori also did a small painting on copper on the theme of the dead Christ in a strong Tenebrae setting, now in Budapest. During Festa’s and Michelangelo’s time these vestments were yet to be thought of, of course. When Tenebrae was celebrated in 1538, for example, it was instead noted that the Pope was wearing a white garment with a fine purple cape.422

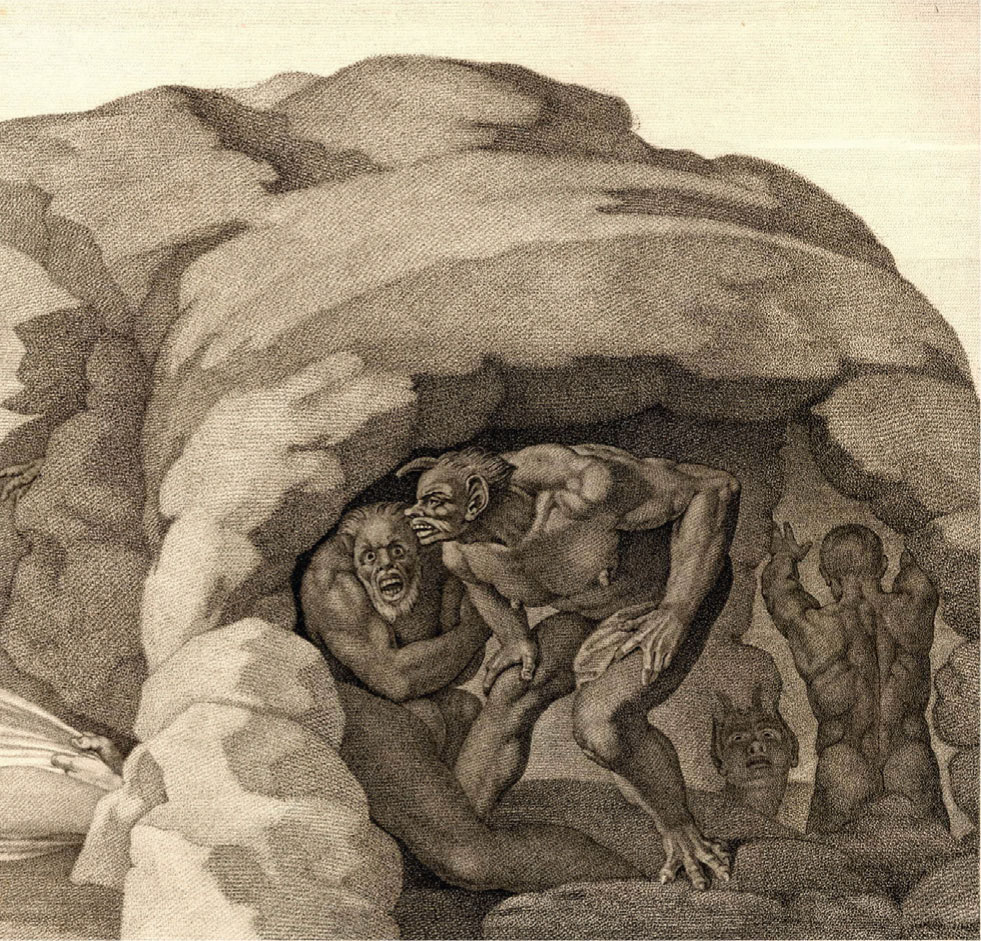

Finally, there is an intriguing relationship between Raphael’s tapestries and Michelangelo’s fresco. The tapestry showing St Paul being thrown from his horse was replaced by Michelangelo’s image of the dead rising from their graves. The tapestry thus corresponds with the general theme of the altar wall painting, showing men and women struggling with the gravity of death and sin, striving upwards towards the divine.423 On the other side of the altar, the removal of Raphael’s scene with the fishermen in their little boat, being called on by Jesus to learn to fish for human souls, was replaced by Charon in his boat, carrying the damned to the torments of Hell. The effect is so striking that it might have been a reason for using the passage from Dante as part of The Last Judgement’s iconography. Michelangelo’s fresco was thus partly modelled upon Raphael’s tapestries, but as a counterpart to them rather than an addition, as an emulation rather than an imitation.

Fig. 16.3 Michelangelo, Study for the Last Judgement, c.1535. Casa Buonarroti, Florence. Red chalk drawing. (Photo: Alinari Archives)

From this it is evident that the Sistine Chapel site in the sixteenth century was not a place of permanence, but of process and change. The liturgical year had a constant outline, but the ceremony, music, and decoration would change abruptly and were under continual reconsideration. This should not come as a surprise in view of the radical changes that are already so well known: the amazing new works of art, produced in a relatively short period of time at the Vatican, show that there was a readiness for change that went far beyond the commonplace. The interplay of works of art, music, and ceremony and the constant reconfigurations of the site made it in many ways more fascinating than any permanent display could ever be. Regarding Michelangelo’s works there, they must be seen as sensitive interactions within a constantly changing interplay of artistic, theological, and ideological activities beyond anyone’s full control. It was not yet known that his contributions would be the ones that would endure, and that they were charged with an attractiveness as silent solitaries that would make them all the more important the more time passed, while other works and their relation to the Sistine Chapel would fade into oblivion.

Fig. 16.4 Conrad Martin Metz, Detail from the lower part of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, 1803. Print. (Photo: British Museum)