CHAPTER 17

Coda

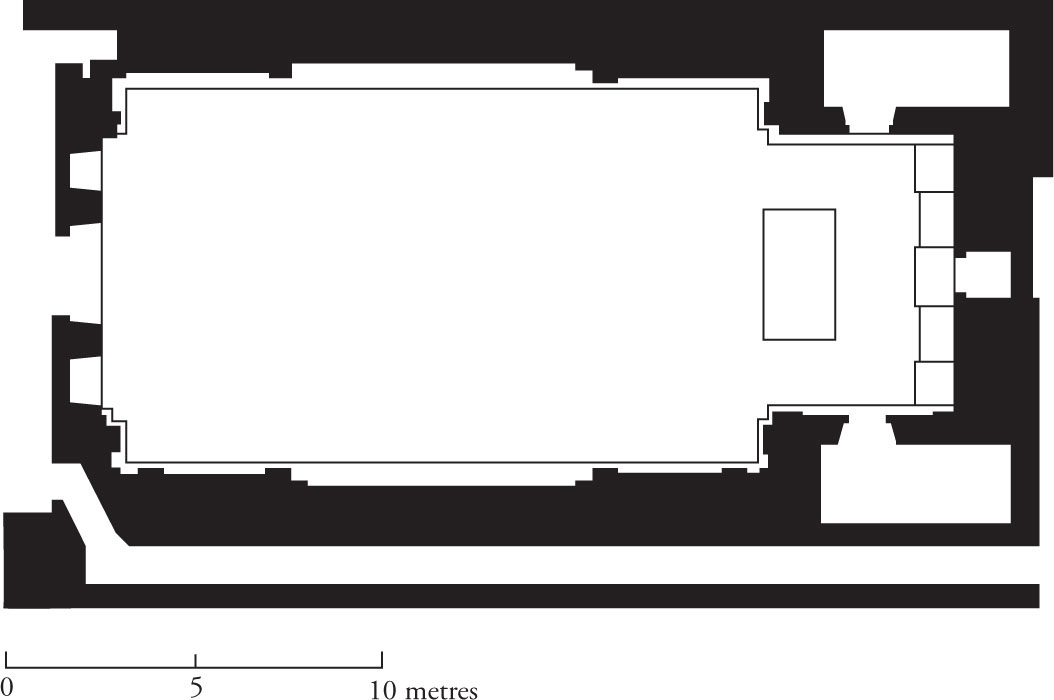

After completing The Last Judgement, Michelangelo received a commission for yet another set of frescoes in the Vatican Palace, which turned out to be his last paintings. For the newly built Cappella Paolina he painted a pair of images representing St Paul and St Peter. The chapel was designed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger in the late 1530s, and the frescoes were executed between 1542 and 1550. Sangallo’s construction was originally only about 16.6 metres long and 10.6 metres wide, but the choir was rebuilt and extended somewhat during the seventeenth century.424 The frescoes are comparatively large for such a modestly sized chapel, both paintings being almost square in format (6.3 by 6.6 metres). A drawing by Sangallo suggests that the altar in the sixteenth-century chapel was free-standing, facing the congregation and with a deep recess behind it, much as in the Medici Chapel (Fig. 17.1). When the chapel was later rebuilt the altar was kept, but was attached to the wall.

The major study of the Michelangelo paintings is Leo Steinberg’s Michelangelo’s Last Paintings from 1975.425 Steinberg was a pioneer in art history in recognizing the importance of spectatorship and site specificity for the artistic designs of the Renaissance and the Baroque, and the suggested viewing of the images in the narrow chapel played an important part in the study.426 Its soundscape ramifications, however, remain to be considered.

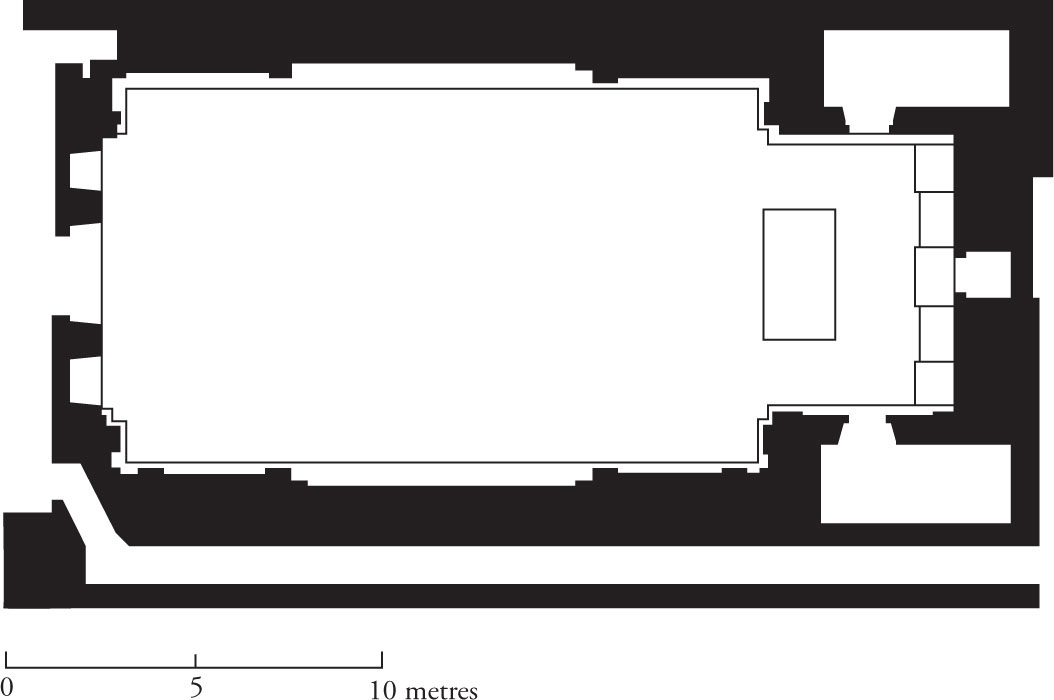

The first fresco painted was the Conversion of St Paul (Fig. 17.2). It shows the scene of this event in accordance with the Acts of the Apostles (9:3–9, my emphasis):

And as he journeyed, he came near Damascus: and suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven: and he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me? And he said, Who art thou, Lord? And the Lord said, I am Jesus whom thou persecutest: it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks. And he trembling and astonished said, Lord, what wilt thou have me to do? And the Lord said unto him, Arise, and go into the city, and it shall be told thee what thou must do. And the men which journeyed with him stood speechless, hearing a voice, but seeing no man. And Saul arose from the earth; and when his eyes were opened, he saw no man: but they led him by the hand, and brought him into Damascus. And he was three days without sight, and neither did eat nor drink.

Fig. 17.1 Ground plan of Cappella Paolina, c.1540. (Figure: Petter Lönegård)

The scene captured by Michelangelo is a detailed image of chaos and turmoil, with the scattered figures going in every direction and even the angels in the sky, appearing together with the Lord, in a frenetic disorder. Paul himself is thrown to the ground by his unruly horse and is at the very bottom of the composition with his back to his companions. Wölfflin and others have claimed that Paul could not possibly see Christ above him from this extreme position, but Steinberg argues that he probably sees him better than the spectator looking at the painting: ‘Paul indeed would see the Christ undiminished, in full, were he not at this moment blinded by this same vision.’427 Three important points connect the figures of the composition: Christ— St Paul—the spectator. With the painting on the left-hand wall of the chapel, the spectator will enter into a direct relation with the saint as he falls, and this will be the path that directs the viewer’s gaze towards the divine on high. The relationship between real and aesthetic space is thus blurred and intermingled.428

Steinberg’s focus is very much on the figure of St Paul, which he describes as ‘one of Michelangelo’s riches creations; a body so activated that its motion fans out all ways—left and right, forward and rearward, to the earth, to the light’. Further, he takes the saint to be a self-portrait, a notion that has won some acceptance.429 Of the two men at the right of the composition, clasping their hands over their heads, he comments: ‘Surely the tightest seam in the history of painting runs between those two at the right to whom the voice of Christ comes as an ear-splitting din: the brazen giant and, partially overlapped, the turntail with the trailing left leg.’430 Still, Steinberg does not recognize that this was an image just as much about hearing as of seeing Christ’s appearance. It is only Paul who sees the light, while all others only hear his voice (or the sound of him, as some translations have it).431 It is the soundscape, the terrifying voice of the Lord, that holds the composition together, or rather, breaks it up into clusters of figures and bodies of sound, scattered in all directions. Those who are looking, directing their eager gaze towards the sound they hear in the sky above them, nevertheless do not see anything. St Paul himself is blinded by the light, thrown into darkness in order to see more clearly the divine truth. What is important is not blindness in itself; it is the insights that it makes possible. It is the commotion of the Lord, the message of the thundering voice, which becomes all-important. Listening is the principle theme here, not looking.

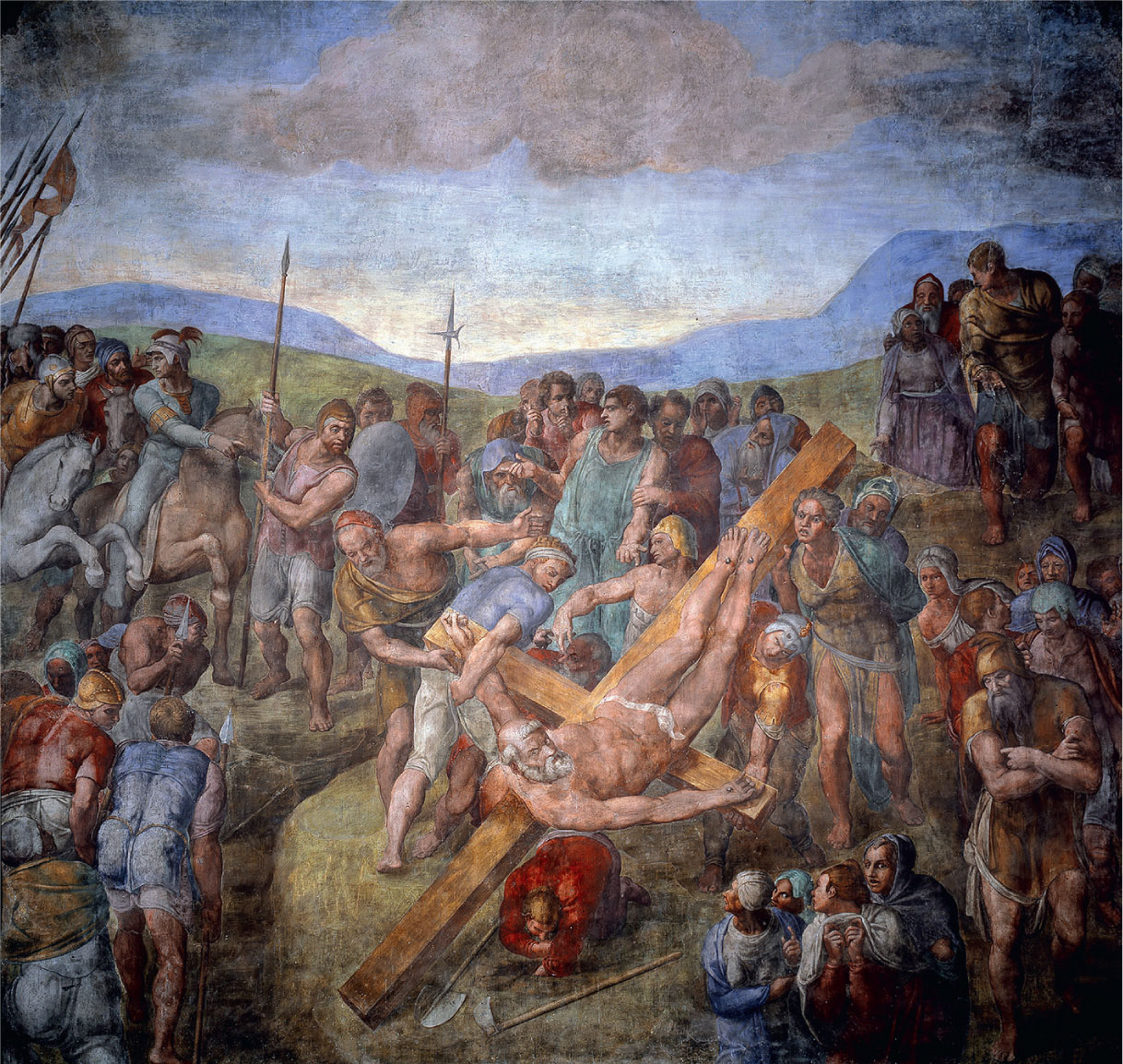

The fresco of the Crucifixion of St Peter (1546–1549), at the right-hand side of the chapel, is no less astonishing (Fig. 17.3). It shows the apostle being crucified in accordance with legend, head down. It was said that when sentenced he did not protest, but instead asked to be put upside down, not being worthy of the same treatment as Christ himself. Like St Paul he is placed at the bottom of the scene and facing the spectator rather than the crowds around him.

Steinberg is again occupied mostly with the exchange of gazes, and how St Peter’s gaze ‘nails’ the approaching viewer:

Fig. 17.2 Michelangelo, Conversion of Saint Paul, 1542–1545. Cappella Paolina, Rome. Fresco. (Photo: Getty Images)

Peter himself, by a fanatic contraction of the abdominal muscles, lifts and projects his trunk towards the beholder, rousing and twisting his upper body in order to see; never has human body summoned such strength for the exertion of looking—not to fix his executioners, not to regard his friends, but to engage every newcomer, every approach.432

As with the St Paul fresco, Steinberg’s analysis is very much in line with the present one—but still not altogether satisfying. The central text here is from the Legenda Aurea:

when Peter came to the cross, he said: ‘Because my Lord came down from heaven to earth, his cross was raised straight up; but he deigns to call me from earth to heaven, and my cross should have my head toward the earth and should point my feet toward heaven. Therefore, since I am not worthy to be on the cross the way my Lord was, turn my cross and crucify me head down!’ So they turned the cross and nailed him to it with his feet upwards and his hands downwards. At the sight of this the people were enraged, and wanted to kill Nero and the prefect and free the apostle, but he pleaded with them not to hinder his martyrdom. Hegesippus and Linus say that the Lord opened the eyes of those who were weeping there … According to the same Hegesippus, Peter began to speak from the cross. ‘I chose to imitate you, Lord, but I had no right to be crucified upright. You are always upright, exalted, and high. We are children of the first man, who lowered his head to the earth, whose fall is signified by the manner of man’s birth, for we are born in such a way that we seem to be dropped prone upon the earth. Conditions are changed, and the world thinks that right is left and left is right. You, Lord, are all things to me. All that you are, and nothing else but you alone, is all there is to me. I give you thanks with the whole spirit by which I live, understand, and call upon you.’433

Fig. 17.3 Michelangelo, Crucifixion of Saint Peter, 1546–1550. Cappella Paolina, Rome. Fresco. (Photo: Getty Images)

St Peter takes the opportunity, then, to turn the moment of his death into a resounding sermon dedicated to the Lord. First, he demands to be crucified upside down, then he stops the angry mob from preventing his death, and finally he praises and calls upon the Lord, explaining the allegorical meaning of his head being ‘lowered to the earth’ as signifying ‘the manner of man’s birth’.

There is, as noted by Steinberg, a quality of stillness to this fresco, compared to the other one in the chapel. The congregation gathered around St Peter is silent, listening to his words and gesturing towards him. A central figure above the saint puts a finger to his mouth to silence any distraction or opposition to the sermon. There is reason, then, for St Peter’s intense look. Those behind him are already listening, he knows; now he wants the attention of the chapel’s visitors. All in all, this is an image of gathering a congregation and preaching the word of God—complementing the listening figure of St Paul on the opposite wall.

The Pauline Chapel was built with specific functions in mind, like the other rooms of the palace that were connected with the church of St Peter’s.434 The consecrated Host was kept and displayed here, and several specific events related to its functions. Thus on Maundy Thursday, after Mass in the Sistine Chapel, the host was taken to the Pauline Chapel to be symbolically buried. The chapel was also used during the conclave and the cardinals would gather here to cast their votes. There were other functions as well, each of which can be linked to the painting’s iconography in a very general sense. St Peter and St Paul, as is well known, were central to anything that took place within the chapel; their overturning, so to speak, may have been seen as fitting images for a chapel of transition, where cardinals and popes were assigned. The underlying theme of divine voices has to be explained otherwise.

The Pauline Chapel was also the papal singers’ chapel, where their daily masses were sung and Divine Office was performed.435 The singers were to assemble in their chapel ‘when they heard the ringing of the palace bells’ and there they ‘performed all the antiphons, responsories, hymns etc.’436 Often these routine events took place without the presence or interference of Church dignitaries. It has been suggested that these were the occasions when the most important musical development of the sixteenth century took place, from simple Gregorian plainchant to advanced polyphony and the introduction of extraliturgical elements, such as the motet, leading up to the birth of opera in around 1600.437 Even more so than the Sistine Chapel, the Pauline Chapel represented the Renaissance’s shift away from larger to smaller musical spaces and the establishment of chamber music ideals—modest reverberance, aural clarity, and intimacy.438 The most significant innovations in the Vatican thus took place outside the officially important events of the church. The Pauline Chapel was the site where the most skilled musicians and composers of the Catholic world gathered, until the rise of the opera houses in the eighteenth century made other careers more interesting. Free from the interference of the ecclesiastical and princely authorities, music was performed to honour God only and with few other considerations, so that it can be said that this music is best understood ‘as a sort of sacred chamber music’.439

During these creative exercises, the singers had before their eyes the frescoes of Michelangelo showing the powerful voice of Christ, the ecstatic attentiveness of St Paul, and the preaching of St Peter; images showing how the sounding voice alone—the spirited air, as Ficino would have it—can frighten, convert, and convince even the most unrepentant.440

In the final decades of his long life Michelangelo was much occupied with architectural projects, mainly the building of St Peter’s but also the construction of the Capitoline palaces, the Palazzo Farnese, San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, and the Porta Pià. Unfortunately, it is not within the scope of the present study to go into these projects in detail, nor how problems of spectatorship, site specificity, and soundscape affected his plans. It will have to suffice to say that for many of them, as the later adjustments, changes, and rebuildings show, these factors were always close at hand in Michelangelo’s work.

At St Peter’s it seems that he insisted on a central church plan and that his work was largely focused on this issue.441 The most important contributions by Michelangelo were the cupola and the crossing, in its original conception an enormous acoustic chamber for the production of echoing soundscapes and voices, floating in the bright, powerful structure. Later, Bernini changed the concept of the building into a more rhetorical structure, beginning with the ethereal light surrounding the dove of the Holy Spirit, converting into the empty chair of St Peter, and passing into the architectural structure of the basilica and reaching all the way out to the gesturing angels of Ponte Sant’Angelo.442 Michelangelo’s concept for St Peter’s is best appreciated when standing at the end of the present nave, contemplating the tomb of St Peter below and looking up at the massive cupola above, and experiencing its immense and heavy impact. What is known of Michelangelo’s ideas for San Giovanni dei Fiorentini and Santa Maria degli Angeli points in a similar direction: the construction of dramatically enclosed rooms for strong acoustic sensations, rather than platforms and scenes for rhetorical preachers or performers.

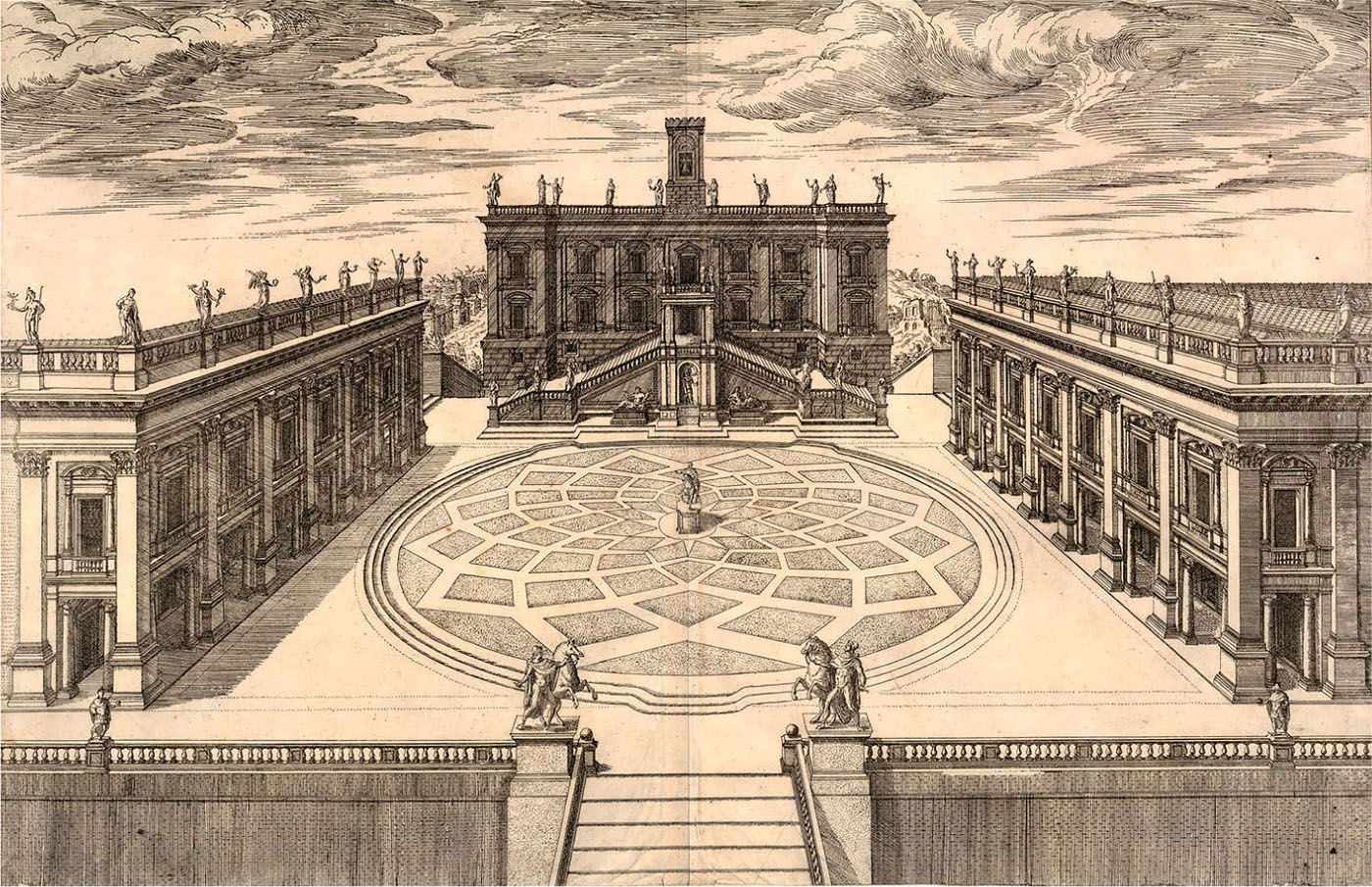

Fig. 17.4 Michelangelo, Palaces and Piazza of the Campidoglio, 1537. Rome. (Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg)

The Capitoline buildings, meanwhile, continue to adjust to their exceptional siting, welcoming and transporting visitors in endless streams down the centuries (Fig. 17.4). Most reach the Piazza del Campidoglio by the cordonata designed by Michelangelo—a long, ramped stairway flanked by two black Egyptian lions at the start and a balustrade with sculptures representing the Dioscuri, the emperors Constantine I and II, a pair of antique trophies, and two columns at the top. Strolling up the hill, the statue of Marcus Aurelius gradually appears, almost as if in motion. The sense of symmetry and of being surrounded by architectural wonders becomes even stronger as the visitor reaches the piazza, with the two large palaces on each side. It is the statue of Marcus Aurelius that departs from this system, confronting rather than adapting to the visitor. The site shows that architecture is not only about constructing buildings, but just as much about the creation of space and environment. Michelangelo pushes the buildings away from the spectator and makes them appear, not as the heavy blocks that they really are, but as interactive scenery. The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, on the other hand, acts aggressively on spectators and surroundings. Through its appearance and gesture it commands and controls the piazza, its architecture, and its visitors: ‘There could be no clearer demonstration of architecture as environment and sculpture as act. Between the two, the world is shaped for human behavior and is made to describe and encourage it.’443 Thus, the Campidoglio sets up a logic of its own, firmly structured but open for interaction with visitors.

When in the late 1530s Michelangelo was commissioned to design the Campidoglio, most Romans already had a long-established relationship to the place.444 What he was asked to do was not merely to construct something out of nothing, but rather to pull the place together in a representative fashion. The site itself was already legendary, because of the ancient temple to Jupiter that once stood on the hilltop, the piazza’s function as a meeting place for the Roman Senate since the High Middle Ages, the crowning of Petrarch here in 1341, and so on. The artist himself lived close to the foot of the hill, and the Campidoglio was where he received his Roman citizenship just a few years before he was given the commission to redesign the place.445 Besides such preconceptions and traditions, Michelangelo was asked to fit in a number of practical functions, most importantly the offices of a number of guilds, a prison, and a large bell in a bell-tower.446 This was the bell of the Roman people that marked out city life. In addition to many routine and often solemn events, the bell with its sonorous clang also signalled the beginning of the Roman carnival and other important occurrences.447 Michelangelo had it removed to its present central position. No less important were the splendid classical sculptures that had been placed here, not only the Marcus Aurelius given by Paul III in 1537, but also several other works donated since the time of Sixtus I, who in 1471 made the first important donation of antiques to the Roman Senate.

The choice of Marcus Aurelius as a centerpiece for the Campidoglio has been discussed many times, and has been seen as representing both the Pope and the Emperor, as well as the Roman people: ‘It is difficult to explain the choice of Marcus Aurelius, not because the meaning of the transfer is unclear but because it had so many meanings’, as James Ackerman exclaimed in 1970 after years of debating the iconographical issues.448 In searching for a site-specific meaning instead of a political or literary one, new possibilities appear. It is not only that the statue is extraordinarily functional as a component of the site, in its integrations and relationships with the overall design, it was that Marcus Aurelius himself was at the time of this particular donation already associated with the site, the Capitoline Hill. About twenty years earlier, in 1515, Pope Leo X had donated a series of reliefs of the triumph of Marcus Aurelius (Fig. 17.5). In the background of one can be seen the temple to Jupiter on the ancient Capitoline Hill. As this is the only known representation of the Capitol from the classical period, it is probably the reason why it was decided to move the reliefs to their present location.449 The reliefs were first on the walls of the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori and were then moved to the staircase in 1572. With the emperor having become so firmly associated with the Campidoglio site, it was logical to place the equestrian statue there too. It functioned as a reference to the importance of the site rather than to the person represented; this is a place where down the centuries even emperors had come for political reasons and to celebrate.

Michelangelo thus had to adapt his design to a number of features beyond his own or anyone else’s control, from the natural shape of the hilltop to historical events long past to various donations by important rulers. He probably knew well that he would never see the designs realized in his own lifetime. It took centuries for the Campidoglio to be completed, and when Michelangelo died, not even the main facades of the palaces were built. The present paving of the site was only laid in 1940. For its completion, later architects and designers have relied heavily on the prints by Etienne Dupérac made from Michelangelo’s models and drawings (Fig. 17.6). Michelangelo’s creative contribution lay very much in an understanding of the site and what it already was, and in transforming it through a creative intervention that involved the coming generations. It tells us a great deal about Michelangelo the artist. His genius consisted in his ability to see better than others what was possible to achieve at a certain site, and how to both maintain and revolutionize it. He had an informed and highly strategic relationship to his predecessors, and he knew how to successfully launch artistic ideas into the future. In the making of one of the most successful sites in the history of art and architecture, Michelangelo would not rely solely on his own artistic capacity, showing that he knew how to draw on what was already in place and to strategically relate it to the shape of things to come.

Fig. 17.5 Unknown artist, The Triumph of Marcus Aurelius, c.180. Capitoline Museums, Rome. Marble relief. (Photo: Alinari Archives)

The design of the Campidoglio and other similar works show clearly how aware Michelangelo was of the important relationship between construction, place, and visitor. All the sites he built seem imbued with his own unique style and fashion. They enhance an awareness of both the senses and the intellect. At the Campidoglio, spectators are encouraged to relate more fully than usual to the built environment, to sense the wind blowing through the arcades and the piazza, to listen more attentively to the soundscape, and to have their bodies choreographed by stairs, sculptures, buildings, and inscriptions.

Fig. 17.6 Étienne Dupérac, Palaces and Piazza of Campidoglio, 1568. Engraving. (Photo: British Museum)

This essay, in conclusion, points to the importance of siting Michelangelo’s art—as well as the visual arts in general—and how works of art interact with their sitings, integrating spectators and soundscapes with their appearances. An example, closely related to the one with which I began this essay, drawn from outside Michelangelo’s art is informative here. It concerns the goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini.

Judging from his autobiography, Cellini was a villain—a rapist and a murderer. Nevertheless, it is possible that it was on false grounds that in the 1530s he was thrown into one of the deepest and darkest subterranean prison cells of Castel Sant’Angelo, with a guard in command who was little short of a manipulative maniac.450 In his despair, Cellini took to prayer for the first time in his life. Using a piece of charcoal he found on the ground, he sketched on the prison wall a representation of Christ rising from the dead, surrounded by angels. He directed his prayers and singing to this image, among other songs a Miserere. A gifted draughtsman and trained singer since childhood, there is every reason to believe that the performance was of the highest quality; a private version of the grander ceremony that Gunnar Wennerberg watched three hundred years later. All alone and with the simplest of means, Cellini recast the prison cell as a sacred site.

In many ways such testimonies bring the art of the Renaissance closer to our own time than Cellini’s well-preserved bronzes and works as a goldsmith. Together they bring out the complexity of the art historical enterprise, how ancient works of art can influence and instruct us today, and how modern life affects our understanding of the past.

Leaving a site behind can be a somewhat unsatisfactory experience; it is not the same thing as reaching a definite conclusion or the final sentence of a written narrative. Instead, visitors take with them half-unarticulated memories and impressions. For a long time afterwards they may still be attempting to piece them together. The site is not yet exhausted and the process of siting continues. As for Michelangelo’s work, there is above all the Sistine Chapel, where both the ceiling and the wall fresco must be understood as site-specific interventions just as much as natural extensions of what was already in place; there is the embracing Medici Chapel, where the statues are actively calling attention to their delicate site specificity; and, in yet another variation, there is the site-specific distribution of sculptures in the tomb of Julius II. In all three instances, it is striking how spectatorship and soundscapes have been site specifically related to. The displacement of statues such as the Roman Pietà or Bacchus reminds us of the importance of the siting for every experience of a work of art. The many unfinished statues point to Michelangelo’s continuous struggle with carrying individual works over into conceptualized and site-specific objects. Many of them appear even today as still-to-be-sited. The Campidoglio appears as a masterpiece of site specificity for the ages. In all this, Michelangelo was not primarily a narrator or maker of precious objets, but a developer of extraordinary sites, a carver of particular ambiences, and a shifter of things already in place. In that sense he was not only forward-looking, but someone who intensively interacted with the past and constantly discovered and defined new aspects of it. As a master of the site he was knowledgeable about what was still undefined; in order to control the thetic, he made himself fully aware of the chora. In line with the philosophy of via negativa, his works are reductions and refinements of what was always and already somehow at hand.

Finally, it is time to acknowledge the ideological and didactic advantages of an art history that pays closer attention to siting. As a complement to historicism and narratological approaches, this can result in new ways of writing about and understanding art. The concept of siting has equally philosophical and artistic foundations, being rooted in art history just as much through the works of Jaques Derrida as of Eva Hesse. While much scholarly activity has made itself dependent on mediated information and reproduction, siting brings any investigation closer to a direct encounter with works of art. Such an attitude serves to encourage greater attentiveness towards the presence of the world as well as the human senses; it acknowledges not only the material objects, but soundscapes and abstraction as well. It weakens the dichotomy between body and intellect. Focusing not only on works of art as such but on their siting as a process—both for artists and for audience—such art history resists the commodification of artistic and aesthetic objects and promotes an understanding of art as part of a lived experience.