AUTHOR’S NOTE

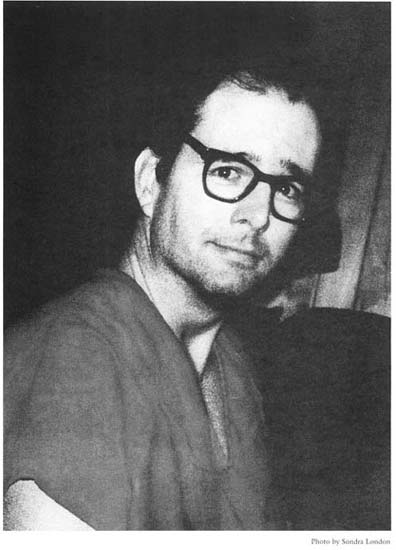

BY SONDRA LONDON

It has taken three and a half years to complete the story of how Danny Rolling became a serial killer. During that time, as he underwent the process of presenting the various facets of his personality to me, he developed insight into the pathology that had controlled and baffled him his whole life. By the time the book was finished, he was no longer overwhelmed by the dark forces that had driven him in the past. He continues to struggle to overcome his tendency to fragment into incomplete personalities under stress. To the extent that he has learned to distinguish his own different voices, and to allow himself to express those thoughts and emotions that had been forbidden, his core personality has become more diffuse, and arguably, more healthy. All he ever wanted was to “just be Danny,” and be loved and accepted, without having to keep his most crucial secrets hidden in the darkness.

My nonjudgmental approach, tempered with my prior experience with serial killers, encouraged him to gradually trust me enough to reveal himself more and more. He could not understand himself, but he could tell me bits and pieces of his story and then as if waking from a dream, turn to me and ask, “What were my words?” Seeing his true self mirrored in my eyes, he began for the first time to come to grips with the disturbed emotions and traumatic memories that had been controlling him from his unconscious mind.

If writing about the fatal process, if drawing its imagery, has not entirely demystified it, at least it has brought it down a notch from the realm of the utterly incomprehensible. Danny had always run from the knowledge of what was going on in his own mind, until he found himself at that ultimate dead end in the house of steel and stone at the end of Murder Road—where he ran into me.

I had my doubts at the beginning. When Danny first started writing to me, he had zero self-esteem, and only a desperately spurious sense of self-confidence.

He had been alone with his secrets his entire life. He was not proud of what he had become. He was very much aware of me as a female from the beginning. Even before our relationship became more personal, he was in a courtship mode, wanting to please me. But this was a whole new situation. He had always had to fabricate a presentable front to be accepted, but now the only way he could capture the attention of this female was to candidly examine his weaknesses and failures, and reveal what was wrong with him. He wanted to open up to me, but he really didn’t know how. He wanted me to know all about him, but he was intimidated by what he felt to be my superior writing skills. “When it comes to writing, baby, you’re like a Porsche,” he wrote. “I’m more like a go-cart.”

Once Danny Rolling became involved in the interactive process of accounting for his life and crimes, he was surprised at the quality of what he was able to compose. The creativity he has exhibited for me had been obscured, repressed by the weight of layers of self-hatred he had accumulated since birth. The grime of those layers of anger, fear and hatred could only be washed away by tears of genuine remorse, followed by forgiveness, sympathy, encouragement, and love.

It was considerably difficult for me to persevere with studying this complex and troubled man under the given conditions, until together, we could reach the point where he was able to ask himself: “Why, Danny, why did you kill those beautiful people?” Although he wanted to confess, the manner in which it was done became a matter of great concern to all parties.

It’s one thing for an author to stand back at a safe distance and compose a fictionalized account of a seriously disturbed, recently apprehended serial rapist and murderer. It’s another thing to actually get involved with such an individual in real life. Having stayed the course, I can now say that it is a path even angels should fear to tread. State’s attorneys and prison authorities have attempted to defeat our purpose. Family members and friends on both sides have pressured us to cease and desist. Rival journalists have been at their wits’ end to steal our story, even going so far as having thousands of pages of my correspondence released, so they could be incorporated into their own stories. Victims’ families who had sold the rights to their stories publicly threatened to kill me if I sold our story.

Nor has it been easy for Danny Rolling to keep pressing onward with the task at hand, long after being served notice by the State of Florida that he would not be allowed to divert any of the profits from publishing his story to his brother, Kevin, as he had originally intended—at least until the United States Supreme Court affirms the decision they made in 1991 that the so-called Son of Sam laws are unconstitutional. When Danny saw the State intended to prevent him from telling his story by hijacking the proceeds from the publication of any accounts of crimes that he might write in the future, he voluntarily relinquished all of his rights and assigned them to me. State of Florida v. Rolling, London, et al., a civil suit intended to block the publication of his confessions, is entering its third year of litigation at the time of publication of this book.

I remain confident that some day the egregious-ness of this unconstitutional action against Danny Rolling and myself will be affirmed, and through due process, my lawyer will see that my fee is returned, setting an important legal precedent about freedom of speech along the way. Meanwhile, having to fight for the right to write does have that proverbial “chilling effect” that would have provided the decisive disincentive, if our motivation had only been financial gain. Given the conditions under which we have had to work, there have been many times when it seemed impossible for one or the other of us to continue. Still, we managed to press forward toward the goal that has bound us together, ever since the summer of 1992, when Danny asked me to help him explain himself to the world.

As we composed bits and pieces of this story, I compiled them into a series of scrapbooks called The Rolling Papers, which became an impressionistic kaleidoscopic self-portrait comprising all of our graphic and written material in the order of its composition. Along the meandering course of its development, I periodically copyrighted it to protect it from being raided, a fear that was not unjustified, as it eventually did occur.

In 1994, after Danny completed his murder confessions, the material previously compiled in The Rolling Papers was revised, finally emerging after another year’s work as The Making of a Serial Killer. The considerable drama surrounding our personal and professional relationship falls outside the scope of this book, as my own account of the Rolling case appears separately in All the Fallen Angels. There is also a more imaginative work in progress, a series of fables written and illustrated by Danny Rolling on Death Row, collected under the tide Legends of the Black Marsh.

In The Making of a Serial Killer, I have focused on delivering the promise of the title, by staying within the framework of Danny’s point of view, and including only material that contributes to the overall understanding of how a little boy from a law-abiding Christian home could grow up to become his own worst nightmare.

Throughout his entire life, Danny has had to deal with the destructive impulses and behavior arising from the troubled parts of his mind that at times become so vividly differentiated that he appears to actually become another person. While the psychiatrists who examined him for court carefully skirted the “multiple personality disorder” diagnosis for his damaged psyche, instead they concluded that he suffered from a half-dozen noxious syndromes, from “borderline personality disorder” to a form of dissociation known as “possession disorder.”

In writing about his life and crimes, the way he expresses himself varies widely. He is not consciously trying to convey an impression of dissociation. He is still experiencing shifts in behavior and perception. He just writes from wherever he may be, and whatever phase he is in at the moment shapes the style of his story as it unfolds. The book was written over a period of three and a half years, and the man who started out in 1992 writing about his last arrest was not the same one who wrote about the murders in the summer of 1994. It should come as no surprise that a man who could attend church seven days a week in the daylight and rape and rob and stab strangers to death in the night might be capable of quite a range of literary styles as well.

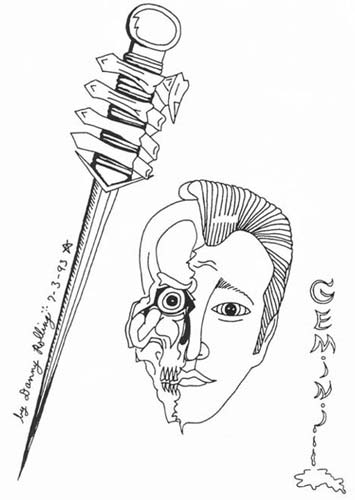

In trying to clarify the confusion of his own mind, he has given names to the two main alter-egos he has experienced. As I have come to know them, the one he calls Danny is his own natural original self—gentle, artistic, bright, polite and devout. But although the original Danny has many fine innate qualities, he would never become a man. At a very young age, as he puts it, “something died.” Because the Danny side of him would always be immature and inadequate in many ways, the Ennad side developed into all that Danny could never be. Ennad is daring, sexually aggressive—a thrill-seeking scofflaw and a stand-up convict. While Danny Rolling is comfortable with these two aspects of his makeup, Gemini, on the other hand, dismays and frightens him.

He describes a serious struggle with rapidly alternating personalities in “Close Call,” an account of an attempted murder in Colorado that Gemini was in the midst of perpetrating when a shocked Danny recoiled from the attack, apologized to the victim and urged her to run for her life from the murder demon that still fought to control him.

The people he robbed after the shootout with his father described him as a “Jekyll and Hyde,” telling People magazine, “He would turn sweet and put the gun down, then he would get mad over something and pick it up.”

In this book I have standardized the shifting and blending of many different voices of Danny Rolling into three type styles. Predominantly, we have the straight narrative text, where Danny Rolling relates his own experiences, speaking of himself as he most often does, in the third person.

The straight narrative text is also used for those portions of the story that were written by myself, relating material revealed at trial, including statements made by his relatives and friends, psychiatrists, and the people he socialized with in Sarasota, Florida, right before the murders.

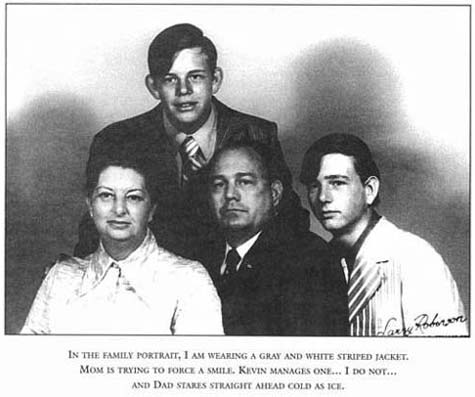

In describing the abuse he suffered as a child, it is of considerable significance that his own memory of the most traumatic events was blocked. When he wrote “Nightmare, on Canal Street,” a year before he heard his childhood described by family and friends at trial, he could remember nothing at all before the age of eight. The more serious abuse, such as being handcuffed and beaten with his father’s police belt, remained buried in his memory until revived by testimony. Of course, he still has no conscious memory of the numerous incidents of witnessed spousal abuse when his mother was carrying him, or his traumatic forceps delivery, or being kicked across the room as an infant. The descriptions of his childhood included here, then, include both his own memories and those recounted at trial.

Secondarily, but growing more predominant toward the end, are the indented sections where the author steps out of the narrative mode and turns toward the audience; you encounter the man himself, sitting on Death Row today in Starke, Florida, speaking directly to you.

Awww, come on, guys…there’s nothing wrong with me that a good piece of pussy and a fifth of tequila wouldn’t cure.

And finally, we have the versification that runs through everything Danny Rolling writes. Granted, it is a bit unsettling to have your hard-core crime scenes laced with chants from Spirits of the Night. But that’s the way it really is. This propensity for rhyming and emoting is an essential component of Danny’s makeup. Hearing or dreaming up these little snatches of song is similar to his visual artwork, in that it is one of the ways he experiences a form of dissociation. A tendency toward schizophrenia runs in his family as well, and that may account for some of Danny’s rhyming, sing-song voices. Gemini likes to versify, but Danny does too.

The use of three alternating type styles provides a fair approximation of what the mind of this serial killer is really like. At times, one style will cut in on the other, or even take issue with an opposing point of view. Other times, you can see one identity through the eyes of another.

Danny’s out, I’m in…Danny’s out, I’m in…

Let’s go hunting…my hopeless friend

While I have noticed clearly differentiated, recognizable personalities, there have also been overlapping and merging of these, as well as the forming and reforming of minor, transitional splinter personalities with names ranging from Cowboy and Michael Kennedy to Maniac and Max Man.

My challenge as his coauthor was to preserve the unique multiplicity of these voices, without either skewing the overall impression by failing to incorporate all parts, or confusing the reader with an unmanageable array of voices. The stylistic mutability of the text is really another manifestation of what this book is all about.

While the bulk of The Making of a Serial Killer was written by Danny Rolling, it has been my responsibility to edit and polish the fragments, arranging and composing them to enhance the narrative flow of the story. While more aggressive editorial intervention was necessary in his early efforts, by the time he wrote about the murders, his skills had matured to the point that the three chapters relating the Gainesville murders could be published word for word, verbatim, exactly as he wrote them. He did say that he put these three chapters through at least five drafts each before sending them to me.

There was a lot more to it than just writing, though. This has been an intensely personal encounter. I have instructed and inspired Danny; probed and cajoled him; encouraged and sympathized with him; provoked him and given him my love. I have explored with him his deepest and strangest secrets, and while there is still much I do not know about this darkly fascinating man, he thanks me for helping him put together the broken pieces of his mind and tells me, “You are the only one who ever really knew me at all.”