Tour 3: Markets and Museums

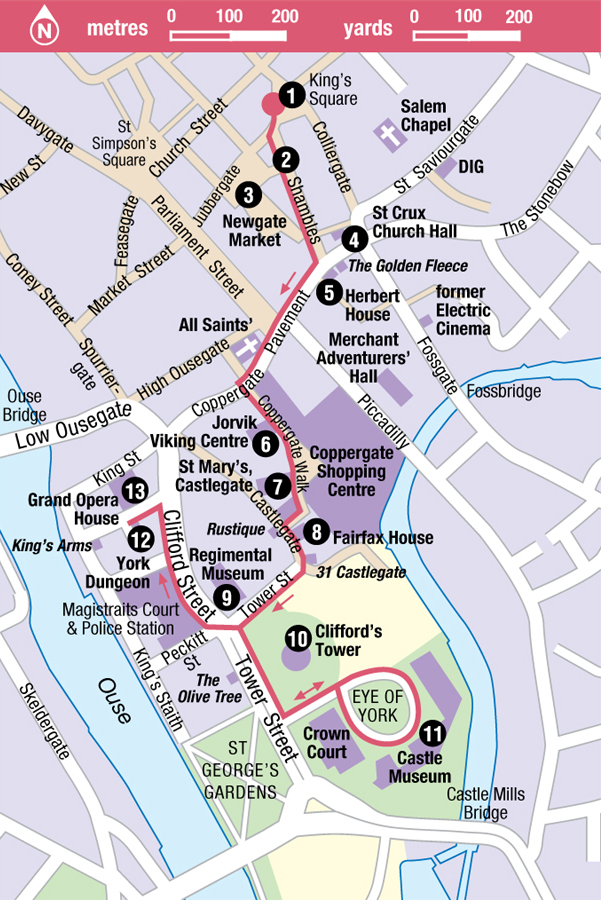

This 1½-mile (2.4km) tour starts in the busy heart of the city and takes in the picturesque Shambles and fascinating Jorvik Viking Centre – all in around half a day

Highlights

A stroll along the Shambles is a ‘must’ on any trip to York. This much-photographed shopping street was mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 and is characterised by its pleasing jumble of timber-framed buildings. The shops may now be firmly aimed at the tourist trade, but the Shambles’ charm is undiminished.

Newgate Market.

APA William Shaw

Even earlier times are recalled at the ever-popular Jorvik Viking Centre, which manages to make history engaging to all ages, without stinting on accuracy or detail. Children will love it – and are also sure to appreciate the Castle Museum, with its reconstructed Victorian street, which you reach later on this tour. Finish the walk with a drink at the King’s Arms pub on the banks of the Ouse.

THE SHAMBLES

King’s Square 1 [map] is the place to be in summer, particularly at lunchtime. Jugglers, acrobats and pavement artists provide some of the best busking entertainment in the north of England. A royal Viking court is thought to be responsible for the name, but the square only came into existence in 1937 when the ancient church of Holy Trinity, King’s Court, was pulled down. Old tombstones from the graveyard are set into the square’s pavements. The square is also home to the city’s newest attraction, York’s Chocolate Story.

The Shambles 2 [map] starts in the southeast corner of the square and gives an immediate impression of what York must have looked like in the 15th century, but without the squalor and the smells. This is one of the bestpreserved and oldest medieval streets in the whole of Europe, although the shop fronts have been restored.

The name Shambles derives from the medieval term for bench or booth, ‘shamel’, on which goods were sold. It was also called Fleshammels (the street of the butchers), for this is where animals were both slaughtered and butchered. The broad window sills are a legacy of the shelves on which meat was displayed – blood and offal would drain away along channels in the cobbled street.

The half-timbered houses lean inwards and are so close that neighbours could shake hands with each other across the street: living in such close proximity meant that outbreaks of the plague could spread rapidly. The butchers’ shops have long gone. Instead there are gift and craft shops and the only odours (all pleasant) come from a pizza restaurant. The old Butchers’ Hall is at No. 41. At No. 35 there is a shrine to Margaret Clitherow – though she probably lived at No. 10. She was a butcher’s wife who was pressed to death in 1586 for harbouring Jesuit priests. She was canonised as St Margaret of York in 1970.

Around the Shambles

Three narrow alleyways on the right lead into the Newgate Market 3 [map], open daily with stalls selling everything from fish to fashions. York’s medieval markets were so famous and grew so large that city-centre property had to be demolished to accommodate them. It is much more modest now, but Henshelwood’s Delicatessen is one of many fine food shops trading here with its tempting array of cheeses, chutneys, oils, olives, pasta and cakes.

Shambles Shops

Although it’s a magnet for visitors, shops on the Shambles aren’t limited to souvenirs. Bag-lovers should head to Cox’s Leather Shop. Incallajta imports Fair Trade bags, woollens and jewellery from Bolivia, Lily Shambles offers contemporary jewellery and W. Hamond, superb Whitby jet. Sweet-toothed nostalgics will love the old-fashioned John Bull Fudge and Toffee Makers. Chocaholics can make for Chocolate Heaven, while savoury lovers shouldn’t miss Ye Olde Pie and Sausage Shoppe.

At the end of the street on the left is St Crux Church Hall 4 [map] (there is no saint called Crux – the name means Holy Cross). What was once the finest medieval church in York was declared unsafe and demolished in 1887 and the church hall built from the stones. Inside are some of the memorials from the original church. The hall is used by various charitable groups for fundraising, so between Tuesday and Saturday you might find homemade cakes, books or bric-a-brac for sale.

Pavement – the first paved street in the city – was the main market area, the place for executions and where ‘minor’ punishments such as whippings and pillorying took place. Overlooking the street is the richly carved Herbert House 5 [map], the finest black and white half-timbered building in the city, now home to a shoe shop. Christopher Herbert, Lord Mayor of London, bought a house on this site in 1557, and it was altered and extended over the years. His great-grandson, Sir Thomas Herbert, was born here in 1606 and became a valet to Charles I. It’s possible that the king was entertained here on a royal visit to York in 1639. He later attended the king on his way to execution and was given the cloak that Charles 1 removed from his shoulders on the scaffold.

JORVIK VIKING CENTRE

Continuing along Pavement towards the tower of All Saints, pass the church to your right and then turn left into Coppergate Walk. This was the site of a sweet factory before it became an archaeological dig often visited by British and Scandinavian royalty in the late 1970s. It was here that the wooden house walls and wicker fences of Viking Jorvik were discovered standing shoulder-high. On the spot where they were found (beneath the new shops), the discoveries have been given a new lease of life in the Jorvik Viking Centre 6 [map] (tel: 01904 615505; www.jorvik-viking-centre.co.uk; daily 10am–5pm, 10am–4pm in winter, pre-booking advised during peak periods; charge, joint tickets available with DIG). This highly popular attraction had a £1 million redevelopment in 2010, and takes account of continuing research into the Viking city that was found on the site.

Learn all about Viking life at the Jorvik Viking Centre.

Jorvik Cenre

You first enter a room with a glass floor, beneath which you can see some of the original archaeological site, while displays on the walls explain the Viking civilisation. ‘Time cars’ then whisk visitors back to a reconstructed Viking world which displays the life and smells of the Viking city. Each house stands on the site of an original Viking property, and the ride features animatronic characters based on archaeological evidence from the Coppergate dig. Market craftsmen are at work, and characters chatter at you in old Norse as you pass. Studies of plant and animal remains in the original dig threw new light on the diet and hygiene of the inhabitants of this huge Viking town as they set about the more peaceful occupations of farming and trade (there were plenty of human fleas and lice in their homes, for example). The time-car ride ends in a gallery filled with exhibits of finds and explains archaeological techniques.

A new, reassessed image of the Vikings emerges, but it is the established reputation of rapists and pillagers that probably attracts the crowds. This rough and ready image still dominates Jorvik’s Viking Festival held every February, which features ferocious battles and have-a-go kids’ sword combat – although poetry and crafts also get a look-in.

Next door is St Mary’s, Castlegate 7 [map] (free). This predominantly 15th-century building has Saxon origins but was declared redundant in 1958 and was bought by the city council for a nominal five pence in 1972. It has the tallest spire in York at 154ft (47m) high, and is now used to house an annual site-specific installation and temporary exhibitions from the York Art Gallery.

Life with the Vikings

At Jorvik there are lots of activities for children, in addition to the journey on the ‘dark ride’. They can also see the skeleton of a Viking killed in battle, handle replicas of tools and objects found in the original dig, and use touchscreens to get a more in-depth insight into the daily life of the Vikings in York. They’re sure to be fascinated by some of the insalubrious details – such as the fact that remains of human faeces were found in toilet pits.

Fairfax House was brought back to grandeur by the York Civic Trust.

APA William Shaw

FAIRFAX HOUSE

Behind St Mary’s continue along Castlegate towards Clifford’s Tower and on the left is Fairfax House 8 [map] (tel: 01904 655543; www.fairfaxhouse.co.uk; mid-Feb–end Dec, Tue–Sat 10am–5pm, Sun 12.30–4pm; guided tours Mon 11am and 2pm only; charge). One of the finest Georgian houses in England, it was rescued from decay by the York Civic Trust. It was purchased in 1762 as a dowry for Anne Fairfax, the only surviving child of Viscount Fairfax, and it has been refurbished to look very much as it would have in its 18th-century heyday.

The stunning interiors conjure up an elegant, forgotten world and the ceilings are all original. The dining room, for instance, where the Fairfax family entertained, has a table laid with fine silverware and porcelain, while the library contains a stunning walnut longcase clock. The furniture and clocks were donated by Noel Terry, the great-grandson of the founder of the Terry’s confectionery business in York. Items on display upstairs include a fine walnut bureau with secret drawers.

The ascent to Clifford’s Tower is rewarded with great views.

APA William Shaw

You enter the house through the former St George’s Cinema – its Greek-style entrance from 1911 is regarded as a piece of early 20th-century architectural history in its own right. The cinema foyer is now the entrance and gift shop of the house.

In Tower Street is the Regimental Museum 9 [map] of the 4th and 7th Royal Dragoon Guards and the Prince of Wales’s Own Regiment of Yorkshire (Mon–Sat 9.30am–4.30pm; charge). The museum has displays of regimental colours, uniforms, medals and models of battles fought all over the world by the two regiments. There are also oil paintings and watercolours, including works by the WWII artist Edward Payne. Contemporary soldiers’ clothing is also displayed, as well as modern ration packs, with their vacuum-sealed meals and water purification tablets.

CLIFFORD’S TOWER

The huge mound facing the visitor at the end of Castlegate and topped by Clifford’s Tower ) [map] (tel: 01904 646940; www.english-heritage.org.uk; daily Apr–Sept 10am–6pm, Oct 10am–5pm, Nov–Mar 10am–4pm; charge) was hurriedly thrown up by William the Conqueror two years after the Battle of Hastings to keep the north country under control. The northern English, helped by the Danes, burned down the wooden castle on the mound within a year. Another wooden keep was built during William’s ‘harrowing of the north’, but was burned down again in anti-Jewish riots in 1190. Some 150 Jews took their own lives when they were trapped in the tower by a mob – it’s thought that the tower was then set alight to try to erase all trace of the horror. There is a plaque to their memory at the foot of the mound.

The stone tower, completed in 1270, was heavily fortified and then wrecked in 1684 when a fire – some say started deliberately – set off the powder magazine and blew off the roof, leaving the structure as it is today.

Towering Views

The ramparts of Clifford’s Tower offer some great views of the city – and although not as spectacular as those from the tower at York Minster, the climb is less arduous. The views are panoramic, so you have the chance to take striking photographs at various times of day. However, you won’t get any summer sunsets, as the tower closes at 6pm.

The tower’s name might well have derived from the powerful Clifford family, hereditary constables in the area, or it could be a reference to Sir Richard Clifford, who was hanged there in 1322 after a failed rebellion.

One of York citizens’ earliest attempts at conservation came in 1596 when Robert Redhead, a jailer, began to pull down the tower intending to burn the masonry for lime. He was stopped after petitions to the government claiming that the tower was ‘an especial ornament for the beautifying of this city’. There are information panels inside the tower.

YORK CASTLE MUSEUM

Beyond the tower mound can be seen what 18th-century travellers regarded as ‘the finest gaol in Britain if not in Europe’. The former Debtors’ Prison (with a clock on the roof) and adjoining Female Prison now house the city’s Castle Museum ! [map] (tel: 01904 687687; www.yorkcastlemuseum.org.uk; daily 9.30am–5pm; charge), named after York Castle, which once stood on this site.

The museum is constantly evolving from its original display, which sprang from a collection of ‘everyday things’ gathered together by Dr John Kirk, a Pickering country doctor, during his rounds in rural North Yorkshire. He saw a way of life slowly disappearing and was determined to keep mementoes of its passing.

As a result of a recent £1.7 million project much of the original display has been updated and reorganised. You can view more than 400 years of York’s past, with social and military history covered on a large scale, together with more intimate and personalised objects. Amongst many fascinating items in the collection is a faded and battered cocoa tin. This was taken to the Antarctic in 1908–9 by Shackleton in his failed attempt to reach the South Pole. It was never used, as Shackleton and his team had to turn back before reaching the Pole. Every period is vividly brought to life, including a tribute to the swinging ’60s, complete with mopeds and miniskirts.

York Castle Museum is one of Britain’s leading museums of everyday life, recreating rooms, shops, streets – and even prison cells.

APA William Shaw

Dick Turpin

Born in Essex in 1706, Dick Turpin was the son of an innkeeper, but far from the romantic figure of legend. He joined a gang of thieves, then became a highwayman in 1735. He later shot a man and escaped to Yorkshire, with a price on his head. He changed his name to John Palmer, but was soon arrested again for horse-stealing. He was imprisoned in York Castle Prison. His real identity was revealed when he wrote to his brother for help, signing himself John Palmer. His brother wouldn’t pay the postage, so the letter was returned to the post office, where it happened to be seen by Turpin’s former teacher – who recognised the handwriting. The teacher was asked to travel to York, where he formally identified Turpin. The highwayman was hanged in 1739 and is buried in St George’s churchyard.

Kirkgate

The covered courtyard became the impressive Kirkgate, a cobbled street created from original 19th-century shop fronts and filled with the samples of Victoriana collected by the doctor. Every shop is now based on a real York business from the period 1870–91. Trades represented include grocer, saddler, taxidermist, draper, pawnbroker and more. Of particular interest is John Saville’s chemist shop at the corner of the newly created backstreet, the poverty-stricken Rowntree Snicket, whose occupants used the chemist’s skills as they could not afford a doctor.

The museum eventually expanded in 1952 into the Debtors’ Prison next door. Turn right when you enter and you’ll come to the exhibition, York Castle Prison. It illustrates the harsh conditions that would have been experienced by prisoners in these buildings. Dick Turpin was imprisoned here – he was tried at the Assize Courts next door.

Assize Courts

The Assize Courts, which extend like a wing from one side of the Debtors’ Prison, were built in the years 1773–7. The Courts, which were designed by John Carr, have an Ionic pillared entrance and a figure of Justice carrying scales and a spear on the roof. Restoration work revealed that Justice had not always been even-handed – her scales had been balanced with small coins put into the weighing cups. Courts still sit in the two Georgian courtrooms, each set beneath an ornately decorated dome. Apart from Dick Turpin’s, the famous trials held here have included such social causes célèbres as the Luddites in 1812 and the Peterloo rioters in 1820.

Eye of York

Together with the museum, the buildings constitute three sides of a square. Between them lies a sizeable, circular grassed area called the Eye of York. County elections used to be held here, proclamations were read, and prisoners executed. What so impressed the Georgians was the spaciousness of the exercise yard in front of the Debtors’ Prison, where prisoners could walk and talk to friends through the yard railings. A verse scratched on the yard wall is preserved behind glass:

The picturesque setting of the King’s Arms pub along the Ouse.

York Tourist Board

This prison is a house of care, a grave for man alive

A touchstone to try a friend, no place for man to thrive.

The poet was Thomas Smith, aged 28, who was imprisoned here for sheep-stealing and hanged in 1820.

York Dungeon

Retrace your steps back to the entrance and turn right to go down Tower Street and onto Clifford Street. The York Dungeon @ [map] (tel: 01904 632599; www.thedungeons.com/york; Feb–Oct daily 10.30am–4.30pm (until 5.30pm Easter and summer school holidays), Nov–Jan 11am–4pm; charge) is the city’s own chamber of horrors – complete with blood, groans and mutilations. Dick Turpin, Guy Fawkes, Vikings and witches all feature in this thoroughly ghoulish attraction.

opera house

The nearby Grand Opera House £ [map] (www.grandoperahouseyork.org.uk) opened in 1902 as a music hall rival to the Theatre Royal. It was converted from two buildings: an old warehouse and corn exchange by the London theatre architect John Briggs. It ‘went dark’ in 1956, reopened in 1956 for roller skating, dancing and bingo, and after another period of gloom it is again operating as a theatre, with performances for everything from comedians to musicals. Backstage tours are available in which you learn about the theatre’s history, see the dressing rooms and go on stage. To book, call 0844 847 2322 (charge).

Walk down the street on the left to King’s Staith where, in summer, picnic tables are set out on the riverbank in front of the King’s Arms. This frequently photographed pub often features in the news when floodwater from the Ouse invades its cellars and drinking areas.

The buildings that comprise the Grand Opera House were not originally intended to be a theatre but York’s corn exchange and an adjoining warehouse.

Courtesy The Grand Opera House

Eating Out

31 Castlegate

31 Castlegate; tel: 01904 621404; www.31castlegate.co.uk; Tue–Sun 11am–3pm, 5.30–9.30pm.

Situated beside Fairfax House, this restaurant offers a diverse menu with dishes that can vary with the seasons. During the day, pop in for salads, filled baguettes, or a homemade burger with bacon and cheese. In the evening, mains might include slow roast free-range belly of pork, pan fried sea bream, or assiette of venison. ££

The Golden Fleece

16 Pavement; tel: 01904 625171; www.thegoldenfleeceyork.co.uk; food served: Mon–Fri noon–3pm, 5–8pm, Sun noon–8pm.

York’s oldest and supposedly most haunted pub, it certainly has the old-world wow factor. Stop here for a drink in the beer garden, or a meal cooked using locally sourced ingredients in the cosy dining room. Good wholesome pub fare includes steak and ale pie and fish and chips. Gluten-free meals available. ££

The Olive Tree

10 Tower Street; tel: 01904 624433; www.theolivetreeyork.co.uk; daily noon–2pm and 5.30–10pm.

You get stunning views of Clifford’s Tower at this sleek little restaurant, which sits just across the road from the imposing fortification. The food is modern Mediterranean, and local produce is used whenever possible. There are pizzas and pasta dishes, as well as main courses such as chargrilled fillet of salmon or Yorkshire beef. Desserts might include a rich chocolate orange brûlée cheesecake, served with caramel sauce, or panna cotta with strawberries. ££

Rustique

28 Castlegate; tel: 01904 612744; www.rustiqueyork.co.uk; Mon–Sat noon–10pm, Sun noon–9pm.

This cosy restaurant, tucked away on Castlegate, serves delicious French fare. The three-course set menu is good value. Dishes are French favourites such as moules marinière for starters, with mains like pork with apples and French cider, or fillet of beef with truffles. Save some space for dessert and choose from the classic tarte tatin, traditional crème brûlée or an indulgent pot au chocolat. ££