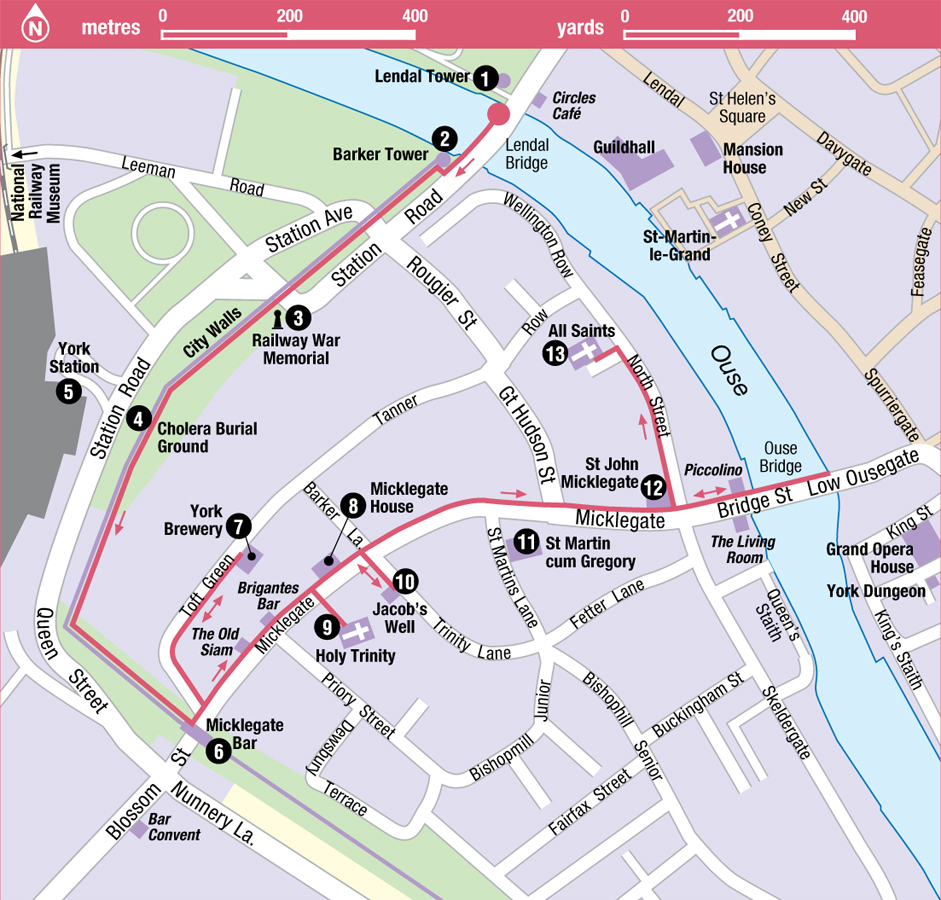

Tour 4: An Aerial View of York’s Railway History

This 1¾-mile (2.8km) walk takes a couple of hours, starting along the City Walls, looking down on scenes of York’s rail-way past, then returns along the old main road from London

Highlights

This gentle walk gives you the opportunity to appreciate the beauty of York’s riverside setting, taking you over the Ouse for a stroll along the city’s superbly preserved walls. You get a reminder of the exuberant optimisim of the Victorian age, with great views of the 19th-century railway station – a cathedral to steam which established a fast link between York and London. There are also reminders of the religiosity of the medieval era, as you pass churches such as All Saints. You could end the walk with a wander along Queen’s Staith, which runs right beside the river. Warehouses here have been converted into apartments and hotels.

Handsome Lendal Bridge crosses the Ouse.

Fotolia

Up the walls

Lendal Bridge was built in 1863 to cope with the extra traffic attracted to the city’s first railway station located south of the river inside the bar walls. Previously there had only been a rope ferry at this point. Work began in 1860, but in 1861 the structure collapsed and several workmen were killed. A new architect was brought in, Thomas Page, designer of Westminster Bridge in London, and a new bridge boasting Gothic-style features opened in 1863. Tolls were imposed until 1894 in order to pay for the cost and compensation to the ferryman.

Lendal Tower 1 [map], on the north bank and once part of the city’s med-ieval defences, was in 1677 given to a London businessman on a 500-year lease and for a peppercorn rent on condition he supplied piped water to the city within three years. He did so through pipes made of hollowed-out elm tree trunks – each half of the city getting water for three days a week in turn. During assizes and busy race weeks water-carriers were drafted in to supply the whole city. It is now a private residence.

City Walls Walk

York’s City Walls make a great walking route. At 2 miles (3.2 km) long, they take around two hours to walk and offer fine views of iconic structures like the Minster – as well as peeks into pretty gardens and courtyards. However, don’t think that the Romans or Vikings strolled around the city in this fashion. The walkway was only constructed in Victorian times – allowing ladies and gentlemen to make an elegant promenade.

Barker Tower

Cross over the river to where the medieval City Walls start again from Barker Tower 2 [map] on the far riverbank. An iron chain once hung between the two towers so that waterborne traders could not avoid tolls. Barker Tower was used as a mortuary in the 19th century for bodies recovered from the river. More recently it has housed a variety of shops and is now a café.

Railway War Memorial

The walls run southwards from here, following the line of the defences which the Romans put around their civil settlement. Walk along the parapet over the top of the busy road leading to the station and below to the left is the white obelisk on the Railway War Memorial 3 [map], commemorating the 2,236 men of the North Eastern Railway who died in WWI. It was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, also responsible for the Cenotaph in London. Behind the memorial are the former headquarters offices of the North Eastern Railway, built in 1906. They now house a five-star hotel. Outside the wall is an area of grass, trees and gravestones – the Cholera Burial Ground 4 [map], where 185 victims of an epidemic in 1832 are interred. Superstitious fears of reawakening the disease are said to have preserved the area from development.

Two towers mark the ends of Lendal Bridge, Barker Tower to the west and Lendal Tower to the east.

APA William Shaw

Barker Tower.

APA William Shaw

Look back along the parapet to enjoy a postcard-perfect view of York Minster across the river. Beyond the city, you can also see one of the city’s finest Victorian buildings, the Royal York, formerly the Station Hotel.

RAILWAY station

Below is York’s ‘new’ Railway Station 5 [map], dating from 1877 and regarded as one of the finest examples of Victorian railway architecture. The plain brick entrance belies the magnificence within – a gracefully curved ‘train shed’ covering four lines of through traffic with the curved roof supported on iron Corinthian pillars.

The roof arches are pierced with quatrefoil patterns and the spandrels decorated with the Rose of York and the coats of arms of the three companies which amalgamated to form the North Eastern Railway in 1853. A £900,000 refurbishment of the entrance area was completed in 1984, giving the outer concourse a more welcoming appearance and adding a decorative old North Eastern Railway semaphore signal. The station is now a listed building.

All railways come to York

York’s first railway station was a temporary affair sited outside the medieval wall near where it turns at a right angle. This station was quickly found to be inadequate, so an archway was punched through the city ramparts (which you walk over) and the railway line came under the walls to a purpose-built station inside – an area now occupied by offices. These were the golden days of York’s Lord Mayor and railway ‘king’, George Hudson, whose proud boast was to ‘mak’ all railways cum t’York’. The new Lendal Bridge and a new road, George Hudson Street, helped more and more railway passengers to get to his station, but the site was too cramped. The terminus was moved back outside the walls to the ‘new’ station on its present site. Although George Hudson fell into disgrace in a shares scandal, York continued to be a geographical and administrative focal point for railways.

A masterpiece of Victorian railway architecture.

APA William Shaw

Under the wall and earth mound at this point was a railway control room for keeping the region’s railways running during WWII. It came into its own when the station was badly bombed during the Baedeker raid on the city in 1942. In the entrance to the station is a restored 19th-century trackside railway signal. It was only taken out of service in 1984.

Changing Faces

Near the railway station, just outside the City Walls, is a statue to George Leeman. A lawyer and politician, Leeman was also a rival of George Hudson, the York ‘railway king’ who at one time co-owned a third of Britain’s railways. He was a major influence in investigating Hudson’s shady share dealings – which led to the latter’s downfall. Leeman then became chairman of the powerful North Eastern Railway Company. This statue was originally of Hudson, but after his demise the head was replaced with Leeman’s. A humiliation indeed.

MICKLEGATE

Leave the rampart walk at the royal entry point to the city, Micklegate Bar 6 [map]. The imposing southern entrance to the city was erected in the 12th–14th centuries, probably over an ancient track from the south leading down to the River Ouse. A succession of kings and queens of England have traditionally entered York here. Although restored in 1737, the barbican – two protective walls extending in front of the gate – was pulled down in 1839 despite the protests of Sir Walter Scott. His offer to walk from Edinburgh to York if the council would change their minds went unheeded. This was another gateway which was often ‘decorated’ with spiked heads, most famously that of the Duke of York in 1460 during the Wars of the Roses. Queen Margaret in Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 3 put the incident succinctly:

Off with his head, and set it on York gates

So York may overlook the town of York.

The last heads to be displayed here were those of Jacobites captured after the Battle of Culloden in 1745. Spectators on these walls in 1644 saw the disastrous aftermath of the Battle of Marston Moor, when fugitives and wounded royalist survivors clamoured for admission with the Roundheads hot on their heels. Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh were welcomed here by pageantry and fanfare when they formally sought entry to the city as part of the York’s 1,900th anniversary celebrations in 1971. A museum in the bar portrays the social history of this ancient gate.

Red-brick Micklegate House.

APA William Shaw

Micklegate Bar Museum

Now under the umbrella of the York Archaeological Trust, this museum reveals the history of the city’s walls, in its exhibition Ring of Stone. Delve into York’s bloody history represented in the Ring of Steel display, featuring Viking invasions, rebellions and civil war. Micklegate Bar was also a home until 1918 and the story of the residents is brought alive in the Life in the Bar exhibition (tel: 01904 615505; www.micklegatebar.com; daily Apr–Oct 10am–4pm, Nov–Mar 11am–3pm, closed Dec; charge).

A wealthy street

Micklegate was York’s most important street – it led to the only bridge in the city over the River Ouse and was part of the long road between London and Edinburgh. Its importance attracted the richer residents of the city and medieval merchants, and leading Georgian businessmen built their townhouses here.

Apart from passing traffic business, Micklegate was close to the quays and the lucrative river trade. Look above today’s shop fronts to see the character and quality of what were once fine town residences. In modern times the street has entered local folklore for the Micklegate Run, a pub crawl from the top of the hill to the bottom. If you turn left, into Toft Green, you can visit York Brewery 7 [map] (tel: 01904 621162; www.york-brewery.co.uk; tours Mon–Sat at 12.30pm, 2pm, 3.30pm and 5pm; charge). This is a local, independent brewer which started in 1996 – the first brewery in York since the 1950s. If you join a tour you’ll see how they use traditional methods to brew the beer – and then have a sample pint.

The Royal Gate

Every monarch from William the Conqueror onwards has passed through Micklegate Bar to enter York – except Henry VIII and Queen Victoria. Tradition has it that they asked permission to enter from the Lord Mayor. Victoria apparently visited York twice, once as princess and later as queen. Both times her visit was said to have co-incided with a cholera outbreak in the city – so after the second episode she apparently remained on the royal train whenever she passed by – pulling the curtains in her carriage so she didn’t have to see the offending city.

Return to Micklegate and you’ll soon pass Micklegate House 8 [map]. Thought to have been built for John Bourchier (1710–59), it is probably the best of the townhouses. Bour-chier’s ancestor, Sir John Bourchier, was one of the signatories to the execution of Charles 1.

Medieval Churches

Opposite Micklegate House is Holy Trinity Church 9 [map]. A church has stood here for 900 years, and it is the only monastic foundation that’s a place of worship to survive in York. In medieval times the pageant wagons performing the religious Mystery Plays started their tour of the city from here.

Outside the church is a replica of the stocks, which were used as a form of punishment and stood here from the 16th century until 1858. The originals are now inside the church in a glass case. Also inside is a memorial to Dr John Burton, a historian on whom Laurence Sterne is said to have modelled Dr Slop in Tristram Shandy. Equally of note is the Walker family memorial, honouring the parents and four brothers of Dorothy, who survived them all and erected the stone. Three of the brothers died in WW1 – another had already died before the war started. The church has an interactive exhibition on the lives of the monks who once lived here. Off Micklegate down Trinity Lane is Jacob’s Well ) [map], a 15th-century timber-framed house with a canopied porch.

Inside Holy Trinity Church.

APA William Shaw

The much-rebuilt Ouse Bridge spans the eponymous river.

APA William Shaw

St Martin cum Gregory

The hill down Micklegate towards the river was a severe test for horse-drawn traffic, and until living memory had stone sets to give horses a better grip. St Martin cum Gregory ! [map], first mentioned in records in 1170, was enlarged in the 14th century but is no longer used for services. It is now a centre for stained glass and events and workshops are held here (www.stainedglasscentre.org; by appointment only). Roman masonry from a Temple of Mithras nearby can be seen in the tower plinth. The medieval Butter Market used to be held outside the church, with produce being brought in from country areas for weighing and testing. William Peckitt, the glass-painter (1731–95), is buried in the chancel.

Jacob’s Well detail.

APA William Shaw

Off on the left is George Hudson Street, formerly Railway Street and before that George Hudson Street – the original name being reinstated in 1971 when the city officially forgave Hudson for the disgrace he brought on York. His rehabilitation continues with the council planning to commemorate his life with a monument.

St John Micklegate @ [map] is a mainly 14th- and 15th-century church, saved from decay by finding a new use in modern times – first as the Institute of Advanced Architectural Studies, then as an arts centre and now as a gastropub.

OVER THE OUSE

Ouse Bridge was built in 1810–21 and is the latest of at least three on the same site. The first had six arches and housed, along its entire length, public privies, a chapel, a toll booth and a prison. It appears early in the city’s historical records because of a ‘miraculous disaster’. So many people crowded on to it in 1154 to welcome Archbishop William into the city that it collapsed. No one died in the accident, so it was hailed as a ‘miracle’ and William went on to become a saint.

Another stone bridge, just as crowded with buildings including a Council Chamber, had its two central arches and the houses above carried away in a flood in 1564. The repaired bridge still had houses on it up to the early 18th century. When there was need for further repairs the city tried in vain to raise money by petitioning the House of Commons for permission to dismantle the City Walls and to use the stone and proceeds for bridge-building.

Looking downstream there is King’s Staith on the left and Queen’s Staith on the right – once the city’s main dock area and still used by barge traffic supplemented by holiday craft. Corn and other bulky commodities came up river to this point to be unloaded by the ‘common crane’. Queen’s Staith was the despatch centre for the butter trade coming from the Butter Market in Micklegate.

In the 17th century some of the trade was not so savoury, as barges parked here to carry away night-soil and dung. Regulations had to be imposed to ensure that cargoes were shifted as soon as they were loaded.

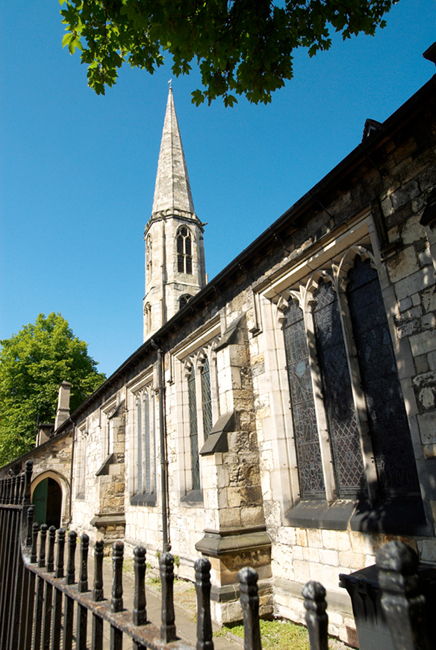

ALL SAINTS church

Retrace your steps and on the upstream side of the bridge take the new elevated riverside walk by Piccolino restaurant and past the Park Inn Hotel to All Saints, North Street £ [map] (www.allsaints-northstreet.org.uk; Mon–Sat 10am–6pm summer, 10am–3pm winter), famous for its stained glass and 120ft (37m) spire, a striking landmark on the river frontage. Although there is Roman stonework in the structure and documentary references to All Saints in 1116, the main style of the church is 15th-century, when the spire was added. Softening the intrusion of the modern hotel across the road is a row of timber-framed cottages to its north side.

The riverfront All Saints Church.

APA William Shaw

Anchoress of All Saints

Dame Emma Raughton was anchoress of All Saints for many years – she was mentioned in documents dated 1421 and 1436. Anchoress comes from the Greek anachoretes – one who lives apart. Her home beside the church contained a couple of ‘squints’ – small openings that allowed her to see church services from her little cell, without joining the congregation. Rules for anchoresses of the time included one forbidding them from wearing linen next to the skin (unless made of coarse flax), another stating that their hair should be cut four times a year, and another which said the only animal they could keep (unless compelled to by need) was a cat.

The wise woman of All Saints

All Saints had a live-in anchoress in the 15th century. She was Dame Emma Raughton, a wise woman who was said to be able to foretell the future and who received visions of the Virgin Mary – the best documented in medieval Europe. She was consulted by the kingmaker Earl of Warwick, and was said to have foretold the dual coronation of Henry V1 – which took place in both France and Britain. Her prophecies were of huge political importance – no doubt why they were so well documented. She was thought to have received her visions at a large statue of the Virgin, unusually depicted without the Child; a shrine with a recreated carving of the original statue and replica medieval flooring is the focus of present-day devotion to the Virgin. In 1910, an anchorite’s cell in mock Tudor style was attached to the southwest corner of the church, with one upstairs room and an outside toilet. At least three women lived there as anchoresses, and later Brother Walter moved in – living there for some years until the early 1960s.

Superb stained glass

There was controversy in 1977 when the carvings in the church roof were restored in medieval colours, making the angels, according to some critics, look like glove puppets. The colours are now more subdued. The church windows are from the 14th and 15th centuries. The East Window of the chancel depicts John the Baptist, St Christopher and St Ann showing the Virgin how to read. Other windows illustrate the Last Days of the World, legends taken from a version of The Prick of Conscience, a 14th-century poem telling of the horrors and pain of the last fifteen days of the world in earthquakes and fire. Another window shows the six Corporal Works of Mercy as set out in St Matthew and are said to be the only complete example of this subject in stained glass in England. It shows a wealthy man visiting the sick, clothing the naked and feeding the hungry.

Among the angels in the glass in the South Choir Aisle is a medieval man wearing glasses – only two other examples of medieval spectacles appearing in stained glass are known, one in the southwest of England and the other in France. Some think that it might be a self-portrait of the glazier.

Looking across the river, there is a view of the Guildhall.

Eating Out

Bar Convent

17 Blossom Street; tel: 01904 643238; www.bar-convent.org.uk; Mon–Sat 8am–4pm.

Just outside the walls, the café inside this working convent serves breakfast until 11am and light lunches with a choice of salads, jacket potatoes, soups, sandwiches and cakes. It’s also licensed, so you can have a beer or a glass of wine too, plus there is a lovely garden. £

Brigantes Bar & Brasserie

114 Micklegate; tel: 01904 675355; www.markettowntaverns.co.uk; Mon–Fri noon–2.30pm, 6pm–9pm, Sat noon–9pm, Sun noon–8pm.

Choose from sandwiches, paninis and light lunches to chargrilled mains, washed down with an excellent pint of ale. ££

Circles Café

East Lodge, Lendal Bridge; tel: 07549 125325; Mon–Sat 10am–4.30pm, Sun 11am–4pm.

Opposite Lendal Tower, this café may be tiny but it’s big on flavour and atmosphere. The lunch menu includes excellent nachos, paninis and sandwiches – try the brie, rocket and cranberry on granary. Good coffee and excellent hot chocolate. £

The Living Room

1 Bridge Street; tel: 01904 461000; www.thelivingroom.co.uk; Mon–Wed, Sun 11am–midnight, Thu–Sat 11am–1am.

Pop in this relaxed bistro for a New York-style salt beef sandwich, or some hearty Whitby cod and chips. Also on the menu: steaks, burgers and quite a few veggie options. ££

The Old Siam

126 Micklegate; tel: 01904 635162; www.theoldsiamyork.co.uk; Tue–Sat noon–2pm, 6pm–1am, Sun–Mon 6–10pm.

Located just beyond Micklegate Bar, this friendly restaurant offers visitors and locals alike an authentic Thai experience. Choose from sharing platters to start with to a huge range of curries, stir fries and set menus for mains. ££

Piccolino

18 Bridge Street; tel: 01904 521155; www.individualrestaurants.com/piccolino; Mon–Sat noon–11pm, Sun noon–10.30pm.

This smart Italian restaurant is one of a chain offering a good range of dishes. On top of pizza and pasta, they also offer mains cooked in a wood oven, such as branzino – seabass cooked with lemon, garlic and parsley. You’ll also find charcoal-grilled chicken and steak. Desserts include tiramisu and panna cotta. ££