Why, they couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.

Union commander General Sedgwick just before he was mortally wounded by

Confederate sharpshooter Sergeant Grace at the Battle of Spotsylvania in 1864.

The word ‘sniping’ or ‘sniper’ is generally believed to have originated in eighteenth-century India where British officers tested their shooting prowess hunting a small, fast bird known as a Snipe. To hit this swift-flying creature with the rifles available at the time took exceptional skill. The use of these terms prior to the First World War was uncommon and, even then, primarily restricted to Britain and her colonies. Elsewhere, in places such as Europe, in British colonial conflicts and in the United States, ‘sharpshooting’, ‘sharpshooter’ or ‘marksman’ were more common descriptions of the accurate firing of a rifle or of a well-trained rifleman. Following the Allied landings at Gallipoli in 1915, English and Australian newspapers began referring to the exchange of fire between the troops as ‘sniping’. As the war progressed sniping became more associated with a specialist skill acquired through formal training — the trained sniper whose job it was to hunt down and kill high-value enemy targets as a priority over shooting any exposed adversary.

The history of sniping is also the history of the development of weapons technology. The earliest firearms were muzzle-loaded with lead ball projectiles fired at low velocity. For ease of loading, musket balls were smaller than the barrel’s diameter, rammed down with a piece of paper, cloth or leather, and would often bounce off the sides of the barrel when fired. This meant that the shooter had little control over the path of the ball from the barrel, leading to poor accuracy and short range. The rifling of firearms — the process of inserting grooves in the barrel to allow the projectile to spin (gyroscopically stabilise) — improved aerodynamic stability and thus enhanced accuracy. While rifled weapons first appeared in the late fifteenth century, the technology did not become generally available in small arms until the eighteenth century. Arguably the first use of a sniper as we know it today was by the Prussian states in the Seven Years War (1756–63). Experienced hunters or Jägers were employed with rifled weapons to act as marksmen, skirmishers and scouts. Their short, heavy and large-calibre (around .75 inch or 19 mm) rifles could out-distance any of their enemy’s muskets.

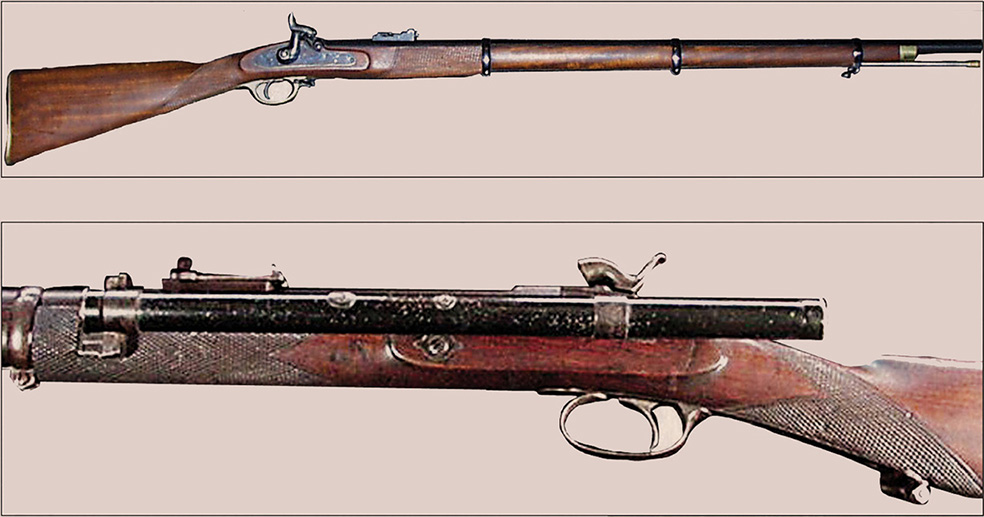

The British Brown Bess musket (top) was routinely outclassed by the new American long rifles (bottom) (AHU weapons library image; long rifle image courtesy of James Blound).

American War of Independence (1775–83)

Among the first to adopt and improve on the German-style Jäger rifles was the American frontiersman. Using German designs, the Americans adapted the rifle by lengthening the barrel and reducing the calibre to .40 and .45 inch (10–11.5 mm), thereby improving the accuracy and velocity of the rifle. By the time of the American War of Independence, a marksman equipped with one of these rifles, such as the Kentucky and Pennsylvanian long rifles, could consistently hit (and sometimes kill) a man-sized target at 300 metres. By comparison, the Brown Bess, Britain’s Land Pattern smooth-bore musket, was rarely accurate beyond 100 metres. One British officer commented acidly that an enemy ‘soldier must be very unfortunate indeed who shall be wounded by a common musket [Brown Bess] at 150 yards [137 metres].’

The American War of Independence provided numerous examples of Americans performing previously unheard of feats of marksmanship with their long rifles. One such feat occurred in October 1777 at Freeman’s Farm, New York, when a lone Kentucky rifleman reputedly shot and killed British officers Sir Francis Clerke and General Simon Fraser at a distance of over 400 metres. There are similar examples of Americans picking off British infantry and artillerymen at distances considered ‘safe’ by the British officers. Indeed on one occasion a colonial marksman, working on the British side as a scout, is reported to have refrained from shooting an exposed American officer in the back out of a sense of chivalry. Had he pulled the trigger, American history may have been fundamentally altered as the officer was one George Washington.

During the American War of Independence one of the British Army’s prime infantry tactics was the employment of lines of infantrymen (‘Redcoats’) firing disciplined volley fire over relatively short distances. This tactic saw their fire resemble something akin to an ‘area weapon’ as individual soldiers were trained to fire in the general direction of the enemy rather than at a particular target. The failure of this tactic against American sharpshooters, armed with the new long rifle and operating in pairs or individually from vantage points and cover, taught the British the value of rifled weapons and highlighted the need for improved tactics.

The First Industrial Revolution in England in the late eighteenth century produced a number of innovations that directly contributed to the production of more accurate and reliable weapons. Advances in metallurgy, for example, led to the production of higher quality and cheaper steel. While many sectors of the British economy benefited from this new steel-producing process, weapons manufacturing was also a major beneficiary. Improved steel and weapons-manufacturing processes, combined with the British Army’s search for a more accurate rifle, eventually led to the development of a new British Army rifle, the Baker rifle.

Advances in technology and the need for new tactics saw the introduction into service of the Baker rifle, in numerous variants, from 1800. Loosely based on the German Jäger rifle, the Baker proved reliable under combat conditions and more accurate at longer ranges than the standard British musket of the time, the Brown Bess (AHU image).

The Baker rifle proved accurate and reliable, and allowed a trained British rifleman to select higher value targets at greater distances than ever before. During the Napoleonic War, British skirmishers armed with the Baker rifle routinely targeted French officers, non-commissioned officers and artillery crews at distances beyond 200 metres. The extraordinary value of this level of accuracy was clearly demonstrated when, in 1809, Rifleman Thomas Plunkett of the 1st Battalion, 95th Rifles, is recorded as having shot French General Colbert at a distance of over 500 metres. A second shot, over a similar distance, also killed one of the general’s aides, thereby proving that the first shot had not simply been a fluke. One British officer, Captain Shore, wrote of the ‘fear and admiration’ of the French for the British rifleman. Indeed, the commander of the French Army in Spain, Marshal Soult, wrote to his Minister of War in 1813 expressing his concern that ‘the loss of prominent and superior officers [was] disproportionate to that of the rank and file’.

Prior to the introduction of the Baker rifle, artillery crews were generally considered immune from rifle fire. They were usually employed too far back on the battlefield to be effectively targeted, except by enemy artillery and, even if they somehow found themselves subjected to a surprise attack by cavalry or advancing infantry, they could protect themselves using deadly canister shot. Canister was similar to a large shotgun shell and fired a mass of lead or iron balls. While devastatingly effective against massed infantry or cavalry at short range, usually less than 350 metres, the canister rounds could not protect artillery crews against British riflemen with Baker rifles. These riflemen could lie outside canister range and fire on the unprotected crews at will. The impact of this tactic was not lost on the enemy artillery commanders and it was not long before French artillery began to acquire protection in the form of hastily erected shields and barriers.

Interestingly, many of the British riflemen at this time worked in pairs. The Baker rifle’s main disadvantage was that, as a rifled weapon, it took longer to load than a musket due to the resistance of the rifling to the ball. A smooth-bore musket could be loaded two or three times faster, a distinct advantage in a fight. Partly for this reason, cost considerations, and a traditionally conservative British Board of Ordnance, the Baker rifle did not replace the standard British musket, the Brown Bess, in the Napoleonic Wars. Instead, the Baker rifle was issued initially to the rifle regiments of the light infantry. These regiments also wore a green uniform (‘Green Jackets’) that afforded better camouflage than the standard red infantry jacket. Clearly military thinking, technology and tactics were evolving to make the individual rifleman more effective than at any time in the past, lessons the British had learnt at great cost during the American War of Independence.

It is also noteworthy that sniping was common in sea battles during this period. One famous victim of a sniper was Admiral Lord Nelson who was felled by a French musketeer aloft in the rigging of the French ship Redoubtable during the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. While the engagement was conducted at close range and was thus ideal for sharpshooting, this event also demonstrated the value of deploying specialist riflemen against high-value targets, another tactic quickly realised and applied to good effect by the British Army in its land battles.

Crimean War (1853–56)

While the First Industrial Revolution at the end of the seventeenth century produced advances in metallurgy and manufacturing processes that directly benefited the British Army, the Second Industrial Revolution (mid-nineteenth century) also nurtured the evolution of rifle production. Accurate weapons could now be mass produced at an affordable cost to allow the relatively inexpensive re-equipping of armies, something most of the major powers were attempting in the second half of the nineteenth century. Related advances in chemistry, paper and metal production also created new technologies and processes for cartridge and bullet manufacture. So too did the development of glass and optical devices, the first of which were affixed to firearms as sights by the middle of the century.

One of these advances was the development of the hollow-base Minié ball. The Minié or Minnie ball expanded on firing to seal the projectile to the bore of the rifle and engage the rifling. This provided improved accuracy and allowed faster loading.

The development of the Minié ball (left) represented a major advance in military ammunition production. As the Minié ball was smaller than the diameter of the rifle barrel in which it was loaded, it could be loaded more quickly and did not require wadding to ‘jam’ it into the barrel, as was the case with musket balls. In addition, while musket balls usually bounced off the sides of the barrel and had relatively poor aerodynamics, the design of the Minié ball allowed it to expand in the barrel and engage the rifling, providing improved stability once it left the barrel. The move from musket balls to Minié ball ammunition thus allowed faster loading and greater accuracy (AHU images).

Another outcome of the Second Industrial Revolution was the production of the Enfield Pattern 1853 rifle-musket. This weapon represented the dawn of a period of serious improvement in marksmanship. Innovations such as a three-groove rifled barrel, a superior percussion lock, a ramp and ladder backsight and improved manufacturing technology, together with Enfield’s production excellence and experience, produced a weapon of unequalled accuracy and lethality. Rushed into service for the Crimean War, the Pattern 1853 rifle-musket proved accurate, long-range, durable and quick to reload. As with the Baker rifle, British skirmishers equipped with the new rifle found that they could engage enemy infantry beyond the enemy’s musket range, and even kill enemy artillery crews beyond the artillery’s canister round range. Equipped with Minié ball ammunition, the Enfield also afforded greater accuracy, range and reliability than the Baker, and was faster to reload. Importantly, due to improved production processes, the British Ordnance Board considered the Enfield affordable as a replacement rifle for the Army. Up to this time, most British regiments were still equipped with smooth-bore muskets.

During the Crimean War, a number of British units experimented with their new rifles and developed effective sniping pairs — one observing and the other shooting. However, while these new mass-produced rifles could fire beyond 1000 metres, the rifleman often had difficulty sighting a target at this distance. While the first British patents for telescopic sights coincided with British experience in the Crimean War, most British commanders were slow to realise the potential of this new weapon; many still relied on massed volley fire. This tactic was soon to change, and both the weapons and the tactics of skilled marksmen were set to feature in dramatically different forms of warfare.

British .577 inch Pattern

1853 Enfield rifle-musket

The .577 inch Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket (AHU image).

The Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket heralded the arrival of a period of skilled marksmanship and proved a weapon of unequalled accuracy and lethality. Not only employed as a standard infantry rifle, it also proved an excellent sniper or sharpshooter rifle. Indeed its accuracy was such that, during testing, it proved capable of hitting targets at distances greater than 1000 metres — targets that were beyond the average soldier’s ability to see. This created a need for some form of optical aid to enable the sniper to extend his normal visual range. Produced in a series of four models, each of which included cavalry and artillery carbines and short rifles, the Enfield had an extended life as a result of its conversion to a breech-loading rifle with the adoption of the Snider mechanism. Known as the Snider-Enfield, this improved version continued to serve as the British Army’s standard infantry rifle until superseded by the Martini-Henry rifle in 1871. A number of Australian colonial regiments were also equipped with the Pattern 1853 Enfield and over a million were sold to the armies of both the North and the South during the American Civil War, where the British Army’s experience with the rifle in the Crimea was put to good effect.

By the time of the outbreak of the American Civil War, both the Union and Confederate armies had access to a range of mass-produced rifles with the latest technological innovations, including rifled barrels, percussion caps and Minié ball ammunition. These rifles included the highly sophisticated and proven British Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle-musket, the accurate American Sharps rifle and the exorbitantly expensive but long-range and extremely accurate British Whitworth rifle. The European conflicts, including the Crimean and colonial wars, provided sobering lessons and the basis for new tactics which were eventually adopted by both the Union and Confederate armies. These lessons and tactics were integrated with a range of technological developments to raise the lethality of the battlefield to a new level. One clear lesson from these earlier wars was the value of using snipers or sharpshooters armed with modern firearms.

However, in the early years of the war, both sides were slow to understand the impact of technology on the military rifle. Officers continued to lead from the front as they had at Waterloo in 1815, artillery accompanied the infantry without protection from sharpshooters and the infantry continued to rely on standing, densely packed ranks of men firing volley shots at the enemy at close range using large-calibre weapons. But there were officers who appreciated the damage a few sharpshooters could do. The Union Army’s 1st Regiment of Sharpshooters was formed in 1861 and comprised marksmen equipped with the accurate Sharps single-shot breech-loader rifle and trained for sniping and scouting. These marksmen were soon nicknamed Berdan’s Sharpshooters after their commander, Colonel Hiram Berdan. Berdan’s Sharpshooters were usually attached to Union infantry brigades as scouts or skirmishers and were often very effective in this role. At the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, Berdan’s Sharpshooters significantly delayed two Confederate attacks, effectively stalling an advance by the Confederate Alabama Brigade on Seminary Ridge.

The Confederate Army also employed trained sharpshooters and equipped them with a variety of rifles including the Sharps, Enfield and even the Whitworth rifle. Because of the cost of importing the Enfield and Whitworth rifles from Britain, and the fact that the importers had to run a Union blockade, the Confederacy never had sufficient modern firearms to equip all its regiments, or even to field an entire regiment of sharpshooters. Nor did the Confederates have the ammunition or technical support for weapon repairs and maintenance enjoyed by the Union. Only the best marksmen were issued the highly sought after sniper rifles and employed as specialist sharpshooters or snipers. To some extent this explains why it was the South that first adopted and developed the sniping tactics from the Crimean War and other recent conflicts.

A British Whitworth rifle (top) and early telescopic sight bottom) as used by the Confederate forces in the American Civil War (AHU images).

Looking to improve on the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle, the British Board of Ordnance commissioned engineer Joseph Whitworth to develop an enhanced version of the rifle. The resulting Whitworth rifle was .451 inch calibre, smaller than the Enfield’s .577 calibre, with an unusual hexagonal bore and bullet shaped to fit. While the Whitfield was significantly more accurate over greater distances, it proved to have two significant disadvantages. It was up to four times more expensive to produce than the Enfield (mainly due to the unusual hexagonal barrel) and it was also prone to fouling. As a result the Whitworth was not adopted by the British Army, but a number were sold by the French Army to the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Also illustrated above is the side-mounted telescopic sight. While this sight magnified objects to four times their original size (that is, a four-power scope) and represented a technological advance in weapon design, tactics and the use of optical devices in war, it was difficult to maintain a zero, would fog up in wet weather and was easily damaged by rough handling, a feature of general military field use. Given the Whitworth’s significant recoil, the attached telescopic sight could also give the unwary firer a nasty black eye.

Confederate sharpshooters were generally attached to regular infantry regiments and allowed a degree of freedom to roam the battlefield ahead of their unit in search of high-value targets. Some Confederate sharpshooters claimed kills at distances beyond 1000 metres. During the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, two Confederate sharpshooters working on Little Round Top killed two Union generals, badly wounded a third, then killed a colonel and up to four other senior officers. In another example of extraordinary marksmanship, during the battle of Spotsylvania in 1864, Confederate Sergeant Grace is credited with killing Union commander General Sedgwick. Sergeant Grace was equipped with a British Whitworth rifle and reportedly fired over a distance of 800 yards (730 metres). General Sedgwick had just told his men, ‘Why, they couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.’ So troublesome were Confederate snipers that at least one senior Union commander, General Rosecrans, ordered his officers to wear smaller badges of rank to make it more difficult for enemy sharpshooters to pick them out.

During the American Civil War both sides realised the importance of optical aids to extend the range of their sharpshooters. The optical industry had expanded in the early nineteenth century and new forms of telescopes were available by the time the American Civil War erupted. By 1860, telescope-equipped rifles had become popular in sporting clubs and were becoming much more accepted than in Europe. While the North was best placed to benefit due to its industrial strength, the Confederate Army also obtained and fitted an unknown number of telescopic sights. While there are numerous examples of remarkable shooting on both sides, there were relatively few military rifles equipped with an optical sight. Those that did exist were usually placed in the hands of the best marksmen. One such Confederate soldier described the training he was given in estimating range, the selection of targets, and how ‘one [man] only from each infantry brigade [was selected] because of his special merit as a soldier and as a marksman … They sent these bullets fatally 1200 yards [1100 metres].’

Many of the sniper tactics developed during the American Civil War would later be applied by Germany and, to a lesser extent Britain, over the next 50 years. German observers were known to have closely followed the performance of imported German technology in metallurgy and optics during the American Civil War. These were observations that were put to good use during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. The British Army, hamstrung by convention and a conservative Board of Ordnance, failed to fully realise the potential of the scoped rifle and continued to teach volley fire by massed ranks of infantry. This would work against them in the Second Afghan War (1878–80), the Boer War (1899–1902) and the early years of the First World War (1914–18).

Technological advances in the closing years of the nineteenth century

Prior to the end of the nineteenth century, a number of additional technological advances occurred in munitions and armaments production. These included the invention of smokeless powder which was more reliable and did not foul the gun barrel. This improvement gave the sniper who wished to remain concealed from the enemy a distinct advantage over any rifleman still using black powder, which produced a signature white cloud when fired. Another key development was the manufacture of the metallic cartridge. Prior to this innovation, a rifleman would have to stand, or at least kneel, to load his weapon with ball and powder, while trying to keep it dry in inclement weather, and prime his rifle or musket with a percussion cap. The use of the cartridge, with breech-loading and magazine-fed rifles, meant that the rifleman could now reload much faster, in any weather, even in the lying or prone position.

So important were these advances that in the closing decades of the nineteenth century numerous major powers attempted to keep abreast of these developments by introducing into their armies a series of new rifles to replace their obsolescent black powder single-shot rifles. In the last 30 years of the nineteenth century Britain, for example, moved from the Enfield Pattern 1853 rifle-musket to the .45 calibre Martini-Henry in 1871, then on to the .303 calibre Lee-Metford from 1888 and finally, in 1895, to the .303 calibre Lee-Enfield, usually referred to as the Magazine Lee-Enfield (MLE) or the ‘Long Lee’. Germany, after employing a series of Mauser or Mauser-style rifles, finally settled on the excellent 7.92 mm Mauser Model 98, with the United States moving to the Model 1892 Krag-Jorgensen rifle.

This new generation of magazine-fed, bolt-action and highly reliable rifles also enhanced the range, accuracy and lethality of the weapon. This was to prove a great leveller, as the second Boer War was to demonstrate, enabling a small, highly mobile armed force to challenge the military might of one of the largest professional armies in the world, that of Great Britain.

Boer War (1899–1902)

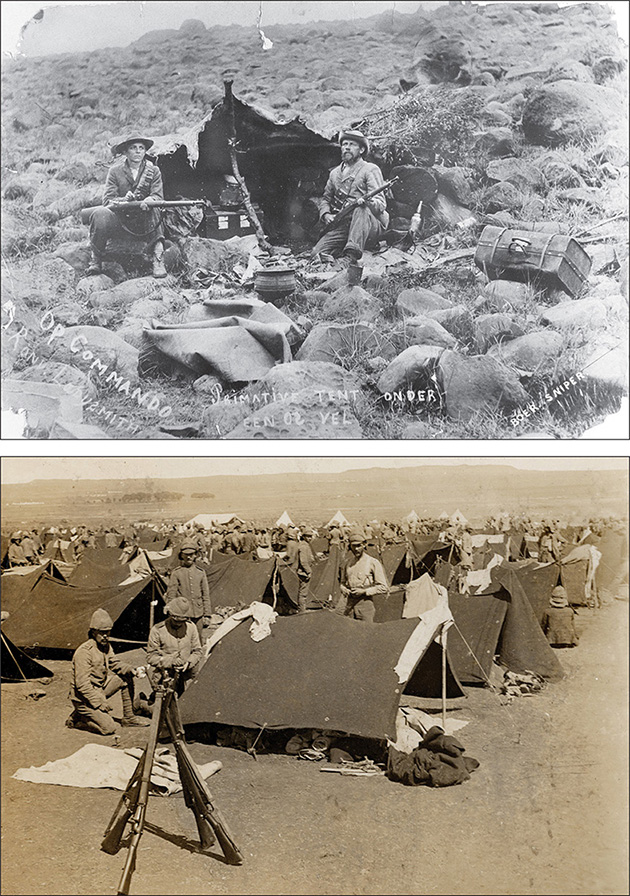

Boer commandos in the field. Nearly all are armed with the excellent Mauser M98 (AWM 129017).

British forces training to charge a Boer position. Note the contrast in the Boer and British Army dress, and the tight formation of the British troops which would have provided an excellent target for the Boer snipers (AWM P00413.032).

The first real test of the capability of these new weapons came during the second Boer War (1899–1902) which saw the British Lee-Enfield pitted against the German Mauser employed by the Boers. While both were excellent weapons and reflected the technological developments in the rifle over the past century, it was the Boer who was able to best adjust his tactics to suit the capabilities of the new weapon. It was also the Boers, rather than the British Army, who were first to employ sniper tactics.

The British Army continued to rely on the firepower of troops massed in formation in open terrain. Little importance was placed on individual marksmanship, long-range shooting or sniping. While the British Army had replaced its red-coated uniforms of the last century, many regiments continued to wear white webbing against their khaki tunics and officers still commonly carried swords and wore unique items of uniform which made excellent aiming marks for the Boers.

These images show the contrast between the way the British forces and the Boers fought. Top is a typical Boer commando makeshift camp which portrays how well the Boers could live off the land (note the annotation in the bottom right of the photograph labelling the image ‘Boer snipers’). The bottom image is of a British tented camp during the Boer War (AWM P00093_007, P00295.061).

The Boers adopted the relatively new doctrine of irregular warfare and possessed an intuitive knowledge of fieldcraft, together with the practical skills of both marksmanship and horsemanship. These skills came from having to adapt to the realities of living in a harsh, unforgiving environment where sheer survival often relied on an ability to hunt, shoot and live off the land. Rejecting the linear tactics of the British, the Boer was more mobile, wore inconspicuous natural colours to blend into the environment and excelled at camouflage. A common tactic of the Boer in initiating an engagement, such as at Spion Kop (Spioenkop) in January 1900, was to use natural cover, carefully select an individual target and engage at long range, often having placed painted rocks at fixed distances as range markers. They were also cunning in deciding when to shoot and when to hold their fire, unwilling to risk exposing their position unless there was a good chance of a kill while also maximising their chance of escaping. In this way the Boers could pick off British officers and non-commissioned officers with impunity at distances of 600 to 800 metres, even killing or wounding the drivers and stokers of British supply trains.

In his 1942 book on sniping, Australian author Ion Idriess wrote that, during the Boer War, ‘the actual out and out snipers were, fortunately for us, comparatively few’. However, with their natural use of camouflage, fieldcraft and marksmanship, and their targeting of high-value targets such as officers at long distance, the Boers were employing typical sniper tactics — tactics that were to be refined to a deadly art in the First World War.

The 100 years between the end of the Napoleonic War and the commencement of the First World War witnessed a revolution in the development of the rifle. Moreover, these new rifles enabled a change in infantry tactics that some forces, such as the Boers, were quick to adopt while others, such as the British Army, were slow to appreciate. Sniper tactics had also been trialled by a number of nations with some, including Germany, formally adopting snipers as members of the Army establishment and creating tactics, techniques and procedures for their employment. By late 1915 both Germany and Britain had adopted a number of sniper tactics developed in the American Civil War. These tactics included the use of telescopic sights attached to a rifle, deployment into a sniper’s ‘hide’ in darkness and remaining hidden from view until firing, experimenting with dummies or various ruses to attract enemy fire and to detect the location of the firer, and the use of artillery to counter enemy snipers. During the four years of the First World War the sniper became an essential specialist in an army’s arsenal as both the Allied and Central Powers fought for dominance on the battlefield. In many ways it was the First World War that gave birth to the modern military sniper.