Preparing for the First World War

Kill one man, terrorize a thousand.

Chinese proverb

Raising the AIF

While sniping was used sporadically by Australians during the Boer War, it was not until the First World War that the Australian military accepted this particular skill as one of the necessary military arts and specialisations. Official acceptance eventually led to the provision of sniper training, the creation of sniper positions on the Army’s establishment tables and the development of a set of tactics, techniques and procedures to integrate the sniper into each of the infantry battalions.

Fortunately for the AIF, the military organisation raised by the Australian government for service overseas in the First World War, a number of its recruits had received a level of military training and were proficient in the use of firearms. The Australian Official Historian, C.E.W. Bean, wrote that ‘the force was to be drawn, as far as possible, from men who had undergone some training.’ Indeed, Australia was the only English-speaking country which had a system of peacetime compulsory military training at that time. Under the Universal Military Training Scheme, which was introduced in 1911, Australian males aged from 12 to 26 years were obliged to undertake various levels of military training. Youngsters aged from 12 to 17 joined the cadets, while those between 18 and 26 years were members of the militia. In addition, under the Defence Acts of 1903 and 1904, all male Australian citizens between the ages of 18 and 60 years were liable for service in the Australian military forces in time of war, although this obligation only referred to military service within Australia and her territories.

These changes encouraged the development of a culture of competitive rifle-shooting that began to emerge from around the middle of the nineteenth century. Rifle clubs, supported by the federal government, became very popular in the years prior to the First World War and existed even in some of the more remote parts of Australia. These clubs, particularly in remote areas, enabled men to meet their Universal Military Training Scheme obligations by simply attending an annual range practice at their local rifle club, although this usually applied only to those men who had served in the Militia for a certain period. All men were encouraged to practise marksmanship and to compete in local and even international sporting shooting events. By the end of 1914, several hundred Australians had qualified as marksmen. In addition, a substantial number of men in the AIF came from the country or outback areas of Australia and were regular users of small arms. These men included kangaroo shooters, miners, farmers, timber-getters and cattle station workers.

AIF recruits being trained in signalling at the Broadmeadows Army Camp near Melbourne, Victoria, April 1915 (AWM DAOD0947).

The AIF’s rifle

The standard military rifle of the AIF was the short-magazine Lee-Enfield or ‘Smelly’ as it was often referred to by the troops due to its acronym, SMLE. At the outbreak of war there were over 87,000 British-made charger-loading Lee-Enfields and SMLEs on issue to the militia in Australia. These were returned and issued to the AIF, with the relatively new Australian Small Arms Factory at Lithgow in NSW increasing production of the SMLE to replace older model rifles.

During the second Boer War, the British Army issued several types of rifles or carbines including the Lee-Metford Mk. II, the Lee-Enfield Mk. I* (MLE or ‘Long Lee’) and the shorter Lee-Enfield Cavalry Carbine Mk. I*. Experience in the Boer War identified several deficiencies in these rifles, prompting the British Small Arms Committee to recommend a new rifle. The result was an evolution in the Lee-Metford and Long Lee designs. While maintaining many of the advantages of the older models, such as their simplicity of operation, robustness and reliability, the new rifle incorporated an improved pattern of sights, reduced weight and barrel length, and a stronger magazine with a charger loading system to quickly load two 5-round clips. From 1904 the British Army — and therefore a number of the Commonwealth armies including the Australian Army — began to replenish its arsenals with the new SMLE.

Australia’s military rifle

in World War I

The rifle, short, magazine, Lee-Enfield (SMLE) Mk. I, one of the most successful military rifles ever produced (AHU image).

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), the British Army was equipped with a variety of service rifles including the Lee-Metford, the Lee-Enfield (or ‘Long Lee’), and cavalry and artillery carbine versions of these rifles. Some form of rationalisation of the different types of rifles was considered necessary by the British Small Arms Committee, as was the need for a new rifle that incorporated some of the lessons from the Boer War. A shortened Lee-Enfield, with improved sighting, a sliding charger guide mounted on the bolthead for easier loading, and long-range volley sights was selected. In 1904 the first version was produced and designated the Rifle, Short, Magazine, Lee-Enfield Mark I (SMLE Mk. I). Small production changes resulted in the Mk. II being introduced in 1906 and the Mk. III from 1907.

While Australia had established its own small arms factory at Lithgow in NSW in 1912 which made the SMLE Mk. III under license, insufficient numbers of this locally made weapon were available at the commencement of World War I. Consequently, the AIF was initially issued with SMLE Mk. I rifles, of which over 87,000 had been returned from militia units for re-issue to the departing troops.

Most Australian troops replaced their older SMLEs with the latest SMLE Mk. III* from 1916 and were also issued improved ammunition. It was this mark that continued to serve the Australian Military Forces until it was replaced by the Self Loading Rifle L1A1 (a derivative of the FN rifle) in 1959. In 1926 the nomenclature of various versions of the SMLE was changed. The above rifle is today more correctly referred to as the Rifle, SMLE No. 1 Mk. I.

With the establishment of the new Australian small arms factory at Lithgow in June 1912, the Army’s SMLE Mark I rifles were gradually replaced with a newer model, the SMLE Mk. III. However, relatively few Mk. III rifles had been produced prior to the AIF’s embarkation for the battlefields of World War I. Consequently, the AIF was largely equipped with the SMLE Mk. I, while some units managed to receive batches of new Mk. IIIs. A change in the nomenclature of the Lee-Enfield in 1926 saw these rifles later referred to as the SMLE No. 1 Mk. I and SMLE No. 1 Mk. III. For simplicity, this book uses the naming conventions in place at the time of the weapon’s issue.

AIF trainees receiving instruction in the SMLE rifle at Mitcham Camp, Adelaide, South Australia (AWM H13827).

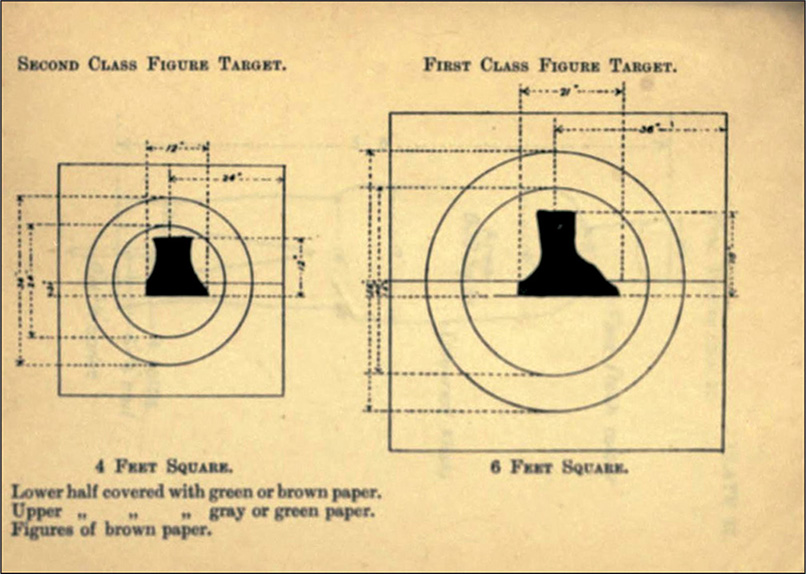

Despite the evolution of the SMLE from Mk. I to Mk. III* during the period of the First World War, it never equalled its rival, the German Mauser, in long-range accuracy. There were a number of reasons for this, not the least of which was that the new SMLE rifle was designed as a battle rifle. This meant that its primary purpose was the provision of a high volume of aimed fire out to 600 yards (550 metres) rather than highly accurate, long-range individual fire. In other words, it was not designed as a sniper rifle. While a reasonably competent shot would be able to hit a six-foot square (1.8 metre) 1st Class, or even a four-foot square (1.2 metre) 2nd Class Figure Target at 600 yards, only a marksman was likely to reliably hit the centre ‘bull’ or central area of the target (see images of these targets below). Essentially the SMLE was only accurate for individual fire out to 400 yards (366 metres), while a marksman could extend this out to 600 yards. Its short barrel, rear-locking bolt and lack of heavy, free-floating barrel made the SMLE less accurate than the Mauser at longer ranges. This was not such an issue for normal infantry use, and the high-volume and rapid fire of the SMLE in many ways compensated for its drop in accuracy over 400 yards. The relatively short distances involved in sniping at Gallipoli obscured the SMLE’s shortcomings as a sniper rifle. It was not until the AIF arrived in France in 1916 that this became problematic, as it had already become for the British Army.

The Australian government’s small arms factory at Lithgow, NSW, circa 1912, just before its official opening on 8 June that year (AHU image).

Prior to Federation, all Australian military equipment had been imported from the United Kingdom. After Federation in 1901, the new Commonwealth of Australia identified a need for a small arms factory to meet the growing requirements of the Army and to complement the existing munitions factory in Melbourne. The decision to establish such a facility was finally taken in 1907, and the site chosen was in the town of Lithgow, approximately 150 kilometres north-west of Sydney. Influencing this decision was Lithgow’s proximity to coal and steel supplies, access to road and rail transport networks, the availability of a semi-skilled workforce and the town’s location, which was sufficiently far from the coast to protect it from enemy bombardment.

An international competition, held to select a company to construct the facility, was won by American company Pratt & Whitney. The Commonwealth Small Arms Factory, covering two acres and employing 250 workers, was officially opened on 8 June 1912. Its first batch of 40 SMLE Mk. III rifles was delivered to the Commonwealth in May 1913. On the outbreak of the First World War production increased to 1600 rifles per week, with a number of early batches exported for use by the hard-pressed British Army. The peak production at Lithgow was 30,460 SMLEs in the financial year 1915–16.

The small arms factory continued to supply the Australian Defence Force during the Second World War, Korean War and Vietnam War. Its production also extended to machine-guns, sub-machine guns and both the SMLE and the L1A1 Self Loading Rifle, which replaced the SMLE in 1959. A total of 640,000 SMLEs were produced.

The Commonwealth Small Arms Factory was privatised in 1995 and became a facility within Australian Defence Industry’s Weapons and Engineering Division. The factory was sold to Thales Australia in 2006 and the now Thales Lithgow Factory continues to supply small arms to the Australian Defence Force.

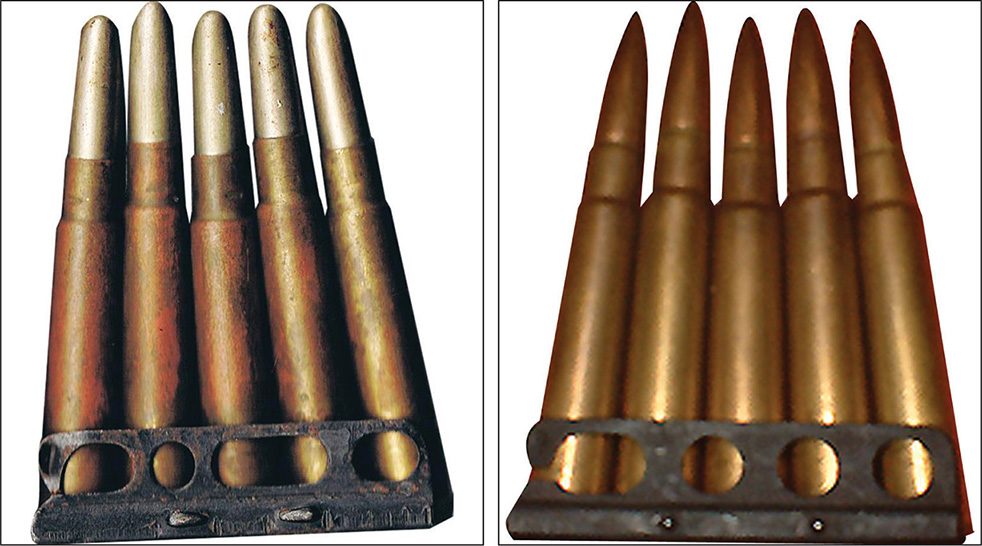

During the first few years of the war, the SMLE also performed poorly at longer ranges because of the type of ammunition employed. The SMLE rifles issued to the AIF were designed for the .303 inch Mk.VI cartridge. This cartridge had been used in the Lee-Metford and Long Lee rifles and had a distinctive round-nosed bullet weighing 14 grams and containing two grams of Mk. I cordite as its propellant. It had also proved unstable at ranges beyond about 500 metres. By 1908 trials were underway to find a cartridge with a flatter trajectory, greater penetrating power and enhanced accuracy at longer distances. In November 1910, the .303 inch S.A. (Small Arms) Ball Cartridge Mk. VII was introduced into service with the British Army. With an 11 gram pointed-nose bullet and 2.4 grams M.D.T. (modified cordite) propellant, it was also lighter than the Mk. VI. The flatter trajectory of the Mk. VII cartridge required the sights of the SMLEs to be altered before this new ammunition could be used, with a small adjustment to the magazine also necessary due to the different shape of the cartridge. Several factors delayed the introduction of the new cartridge in Australia: Army stores held a substantial war supply of the Mk. VI cartridge, the Colonial Ammunition Company in Victoria had not been converted to manufacture the Mk. VII cartridge, and all the Army’s rifles were configured to take the older Mk. VI ammunition. Thus the AIF continued to be issued with the older Mk. VI cartridge. The plan was to either adjust the SMLE Mk. I and Mk. III rifles for the newer ammunition, or exchange them for newly modified rifles at a later date as the Small Arms Factory adjusted production to meet wartime demands and the Colonial Ammunition Company began to produce Mk. VII ammunition. From 1916 the AIF’s original SMLEs were exchanged for modern rifles capable of firing the MK. VII rounds from both British and Australian supplies. The ammunition itself came from the British Army’s supply system as Australia’s Colonial Ammunition Company did not commence manufacturing the newer ammunition until 1918.

.303 inch Mk. VI (left) and VII cartridges (Treatise on Ammunition, British War Office, 1915).

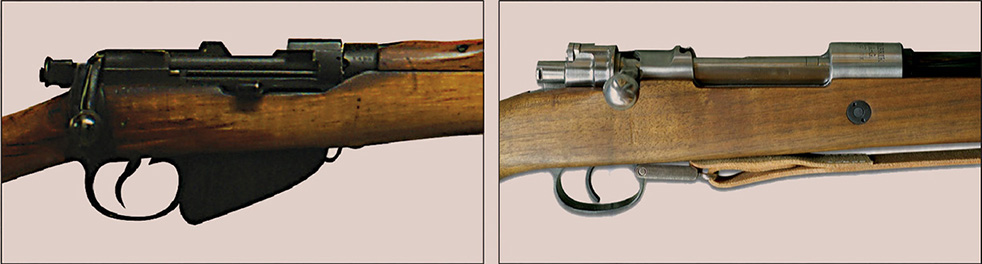

SMLE bolt action (left) and Mauser bolt action (right) (AHU images).

The German Mauser proved a superior sniper rifle to the SMLE during the First World War for several fundamental reasons:

Bolt action: ‘Headspace’ is the distance between the face of the bolt and the rear of the cartridge when it is chambered. The larger the headspace the more room there is for the cartridge, on having its primer struck, to expand backwards as well outwards against the inside of the barrel. The SMLE has a rear-locking lug which holds the bolt in position until it is manually re-cocked. The face of the bolt, which touches the base of the rimmed cartridge, moves backwards slightly when the bullet is fired. A Mauser action rifle on the other hand, has a forward-locking lug, which means that the bolt is more tightly held in place, forcing the rimless cartridge case to expand during firing with very little movement and less variation than the SMLE. As a result, there is very little difference between successive shots from a Mauser, as the amount of gas and the pressure it operates under to propel the projectile down the barrel is largely constant. However, with the SMLE, the greater variation in pressure from shot to shot caused by the bolt’s action results in a loss of accuracy. The best bolt action sniper rifles today still use a Mauser action.

Barrel and ammunition: The Mauser rifle’s manufacturing and steel quality was superior to that of the SMLE and it also had a longer barrel (29.15” and 25.19” respectively). These features, along with the number of twists inside the barrel (3 four-groove twists over barrel length and 2.5 five-groove twists respectively), contributed to greater accuracy over long distances. Twists are grooves inside the barrel that cause a projectile to spin. The more twists, the greater the ballistic stability of the projectile in flight. SMLE ammunition also caused greater erosion and corrosion to the barrel than that of the Mauser and ammunition differences further contributed to the variation in accuracy.

Telescopic sights: Germany had a clear advantage in telescopic sights at the beginning of First World War due to the excellence of the German optical industry. German rifle telescopic sights generally had greater magnification, clearer sight reticules (usually cross hairs compared to the clumsy post sight in most British scopes), a wider field of view and were made of highly durable quality glass. The fact that one of the best telescopic sights produced by Britain during World War I, the Pattern 1918, was based on the German Hensoldt-Wetzler scope, is testament to German superiority.

Both the SMLE and Mauser were extremely durable rifles in most other respects. In the case of snipers, the quality of preparatory formal training further contributed to the initially superior performance of the German snipers. This reality was largely repeated in the Second World War.

Marksmanship training before the war

The Boer War had taught the British and Commonwealth armies some hard lessons concerning musketry and marksmanship. While some of these were incorporated into the design of the British Army’s new rifle, the SMLE, others influenced the training of the infantry soldier. The requirement for the British soldier to be able to shoot as well as the Boer commando was finally acknowledged by senior British commanders. Field Marshal Lord Roberts was partly responsible for this change when, in a speech at Bisley in July 1901, he stressed the ‘necessity of making soldiers good shots’ and urged the people of Great Britain to support the establishment of sporting shooting ranges throughout the country. The Musketry Regulations, which were effectively the ‘Bible’ for British Army small arms training, were updated in 1909 and 1910. These now stated that ‘every soldier should become proficient up to 600 yards [550 metres] at a small object, and a proportion of them to extend this distance to 1,000 yards [914 metres] and 1,200 yards [1097 metres]’, while continuing to maintain the need for ‘continuous fire on the frontage occupied by a body of men’.

In order to deliver this level of proficiency the training syllabus for rifle training and advanced marksmanship was revised to include an extensive series of individual and collective training. At the recruit level, the emphasis was on basic rifle handling, individual fire and rapid group fire. The more advanced practices emphasised individual marksmanship, including timed and moving targets and distance estimation. Having successfully completed this course of musketry, companies moved to a series of collective live fire practices.

Basic musketry training involved four range practices known as parts. This included a total of 27 shooting serials from 100 to 600 yards (from 91 to 550 metres) with each part more challenging than the previous. A soldier had to pass each part in turn before proceeding to the next, but could repeat each practice at the discretion of his company commander until he reached the required standard. For obvious reasons these practices were more challenging for the infantry and light horse units than they were for service corps personnel such as drivers, cooks and storemen.

The targets used were 1st and 2nd Class Elementary (Bulls-eye) and Figure Targets. These targets contained a centre ring or bullseye, and two concentric circles. Each practice was scored and points awarded — four points for a bullseye, three for a hit in the inner circle, two for a hit within the outer circle, and one point for a hit anywhere else on the target. The practices were very competitive with soldiers individually graded as Marksman First Class Shot, Second Class Shot or Third Class Shot. In addition, the combined score of each company was recorded and reported in Standing Orders, leading to intense rivalry between units and sub-units.

The 1st and 2nd Class Figure Target and the 1st and 2nd Class Elementary (Bulls-eye) Target were among the most common targets employed to instruct the AIF’s recruits in basic musketry. The 1st and 2nd Class Bulls-eye targets were of the same dimensions as the Figure Target, but with a solid black centre or bullseye (Musketry Regulations, 1910).

Men who qualified in the above practices would proceed to Part V — Individual Field Practice and Part VI — Collective Field Practice. While the individual field practices were restricted to 600 yards (550 metres) or less, the collective field practices were designed for controlled command fire at longer distances. Both practices involved movement, the use of the contours of the land, available shelter and obstacles, camouflage, and distance and wind estimation. A variety of targets were used in these practices including hidden and falling metal plates, spinning cloth targets and moving targets. Apart from honing individual skills, both types of practice prepared sections for firing as a team and gave the non-commissioned and junior officers much-needed experience in issuing fire orders and commanding men in simulated battle conditions.

There was also extensive use of miniature and sub-calibre ranges where the SMLE rifle was adapted to take .22 calibre ammunition. The Musketry Handbook described these practices as ‘a useful and economical preparation for service shooting — especially where range accommodation is distant or altogether lacking’. Indeed the current Officers’ Mess at Victoria Barracks in Melbourne was used as a small-bore indoor range for the Australian Military Forces between 1881 and 1920. While company and battalion commanders were allowed considerable latitude in devising their program of instructional practices, all soldiers were required to complete the basic course of weapons instruction and meet the requirements of the qualification shoot.

Notwithstanding these changes and an apparent higher standard of marksmanship training, a surprising number of members of the militia failed to achieve the required grade or were not trained at all. According to the Musketry Return for 1907, for example, while over 14,000 troops passed their compulsory annual musketry course in that year, almost 4000, or some 25%, did not complete the course. This situation did not necessarily improve over the following years. The Musketry Return for the year 1910–11, compiled by the Commandant of the new Australian Musketry School established at Randwick, NSW, states that around 33% of the militia had failed to be ‘fully exercised in musketry’, and an unacceptable number of men who did complete their training had failed to qualify. In Victoria, for example, 35% failed to achieve the required standard.

The standard of training was not necessarily any better for those men who had already attended their musketry course but were required to conduct an annual shoot at their local rifle club. In July 1914, reports showed that there were some 45,000 ‘rifle club members duly sworn in the Commonwealth’. However, in the preceding year only around 14,000 had been classed as ‘efficient’. To be deemed ‘efficient’, a man need only turn up at the range and fire at a target. Even if he failed to hit the target with a single shot he was considered to have met his obligation. While there were men who were clearly unable to attend a rifle range given the remote areas in which they lived and worked, this did not explain the enormous disparity in numbers and called into question the effectiveness of the scheme, particularly as within a few months Australia would be at war.

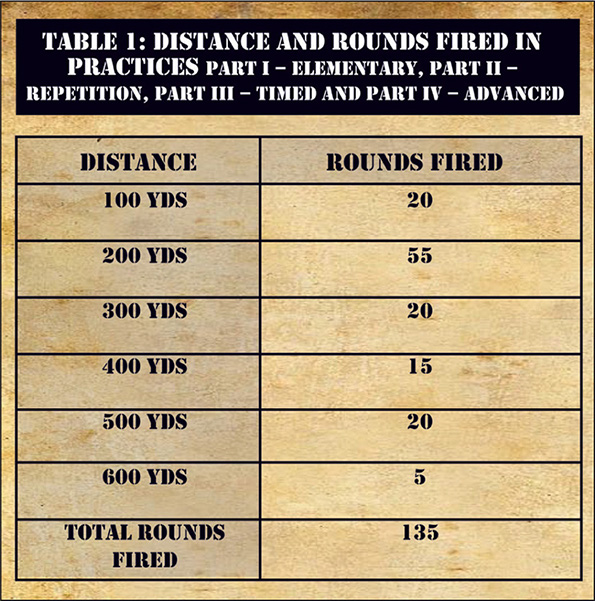

Analysis of range practice data also tells the story of a change in emphasis from high-volume volley fire at extended distances to shorter ranges. This is particularly the case in data from range practices conducted in the years prior to the First World War. As indicated in the table below, more than half the total number of rounds fired were at 200 yards (180 metres) or less, with only five rounds fired at the longest distance of 600 yards (550 metres). This change in emphasis was reinforced in The Musketry Handbook which stated that

… on account of the difficulty of observation 600 yards may be taken as the limit of effective fire of this nature against small targets … Only exceptional targets and very favourable atmospheric conditions will justify soldiers in opening individual fire at distances beyond about 600 yards.

Distances over which rounds were fired during range practices, pre-World War I (Musketry Regulations, 1910).

However high-volume controlled fire was not abandoned altogether. In the foreword to Major Reynolds’ seminal work on the .303 rifle, Lieutenant Colonel Lord Cottesloe wrote that ‘with the highest training and skill thirty-seven shots could be fired at a target in [one minute] by a man in full Service equipment.’ The men nicknamed this the ‘mad minute’. Trials in 1912, which tested the SMLE against the Mauser, recorded 28 rounds per minute fired from the SMLE, far superior to the Mauser’s 14 or 15 rounds. Lord Cottesloe further describes the enormous benefits of this training in the early period of the war when ‘the impact of their rapid fire during the German invasion of France was so great that the Germans believed the British Army to be using machine-guns.’ This is reinforced in a report by the British Army entitled Notes on Experience Gained at the Front, dated 1915, which quotes German officers captured at the front extolling the virtues of British musketry, stating that it was ‘so straight and so quick’ that the German Army had ‘never been able to [attack successfully] over open ground against the British’. While the ‘mad minute’ training appears to have been beneficial in the early years of the war in France, and the focus of firing over distances out to 200 yards worked reasonably well for most Australians at Gallipoli, the lack of sniper and counter-sniper training over longer distances was to prove disastrous by the time the Australians arrived in France in early 1916.

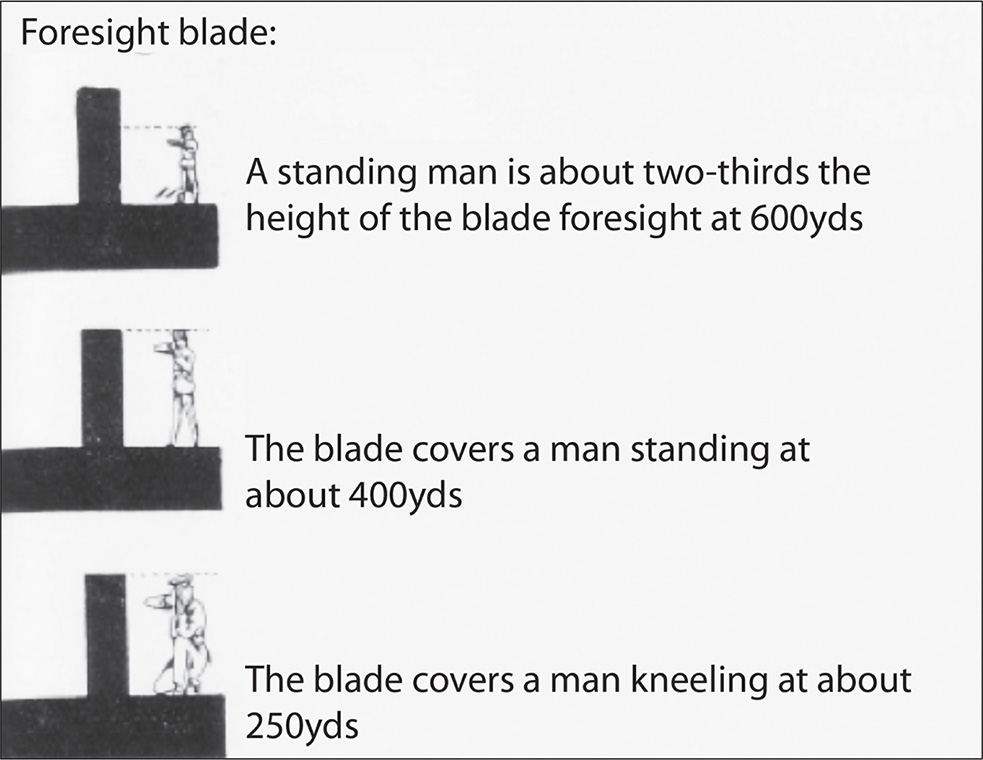

This image, taken from an official Australian Military Forces musketry pamphlet of 1916, shows the typical sight pictures when aiming an SMLE over open sights at 600 yards (550 metres), 400 yards (365 metres) and 250 yards (230 metres). The difficulty in hitting the target at 600 yards is clearly illustrated (Visual Training and Judging Distance, School of Musketry, Randwick, 1916).

The Army-issued SMLE had an open sight, which was typical of almost all military rifles of the period. This open, or combat sight, consisted of a foresight close to the muzzle of the rifle and a backsight towards the rifle’s bolt. The SMLE’s foresight, known as a ‘barleycorn’ sight, was a dark, bold, broad blade designed to stand out against the background of the target. It could be adjusted at the factory or by an armourer to one of three positions in its block to achieve the correct elevation.

The backsight was a sliding leaf design with adjustments for windage; that is, it could be moved left or right to allow for the prevailing wind and for range. The range could be quickly adjusted in 50-yard (46-metre) increments from 100 yards out to 2000 yards (1.8 kilometres) using one hand without losing aim or sight picture — without taking the eye off the target. If necessary, it was also possible to adjust the sight in 25-yard (23-metre) increments. In the cap at the rear of the backsight a ‘V’ notch for the Mk. I or ‘U’ notch in the Mk. III was cut, through which the firer aligned his foresight with the target.

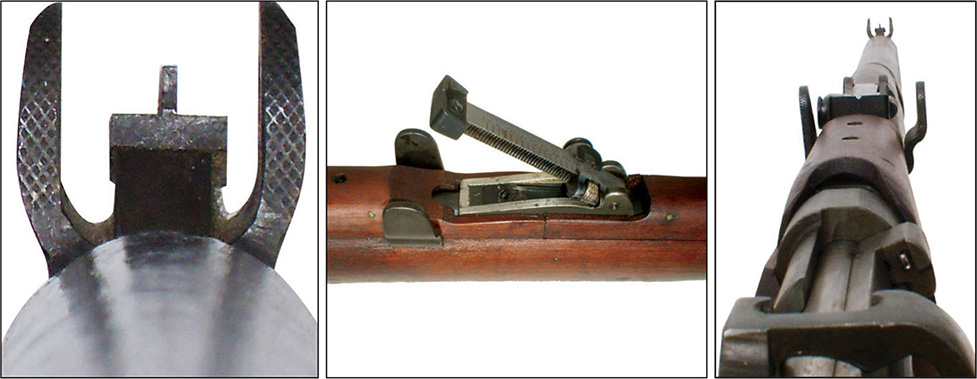

The SMLE’s foresight (left), sliding leaf backsight (middle), with range gradations every 100 yards out to 2000 yards, and the view from the firer’s position (right) (images courtesy of Peter Bruem and Rex Wigney).

An interesting aspect of the early SMLE Mk. I was the long-range volley sights. These sights were copied from the original Lee-Enfield rifle and contained a forward rotating dial sight on the left-hand side of the rifle, paired with an aperture rear sight. They were designed to enable a formed body of men, from a company to a battalion, to theoretically coordinate their fire onto a visible fixed point such as a road junction, building or advancing enemy formation, out to 2800 yards (2.6 kilometres). The 1915 version of Musketry Instructions issued by the School of Musketry in Randwick states that the ‘advantages of Long Range sights for 1600 yards and over [are that they are] (a) Quicker. (b) Equally accurate [compared to normal rear sights]. (c) Less strain to neck muscles while aiming.’ While each rifleman’s fire may have been inaccurate, the joint effect of the body of men firing together could be very effective in breaking up an enemy attack and, before the days of the machine-gun, offered the ability to target enemy troops at extreme range. It also required the firing unit to be densely packed so that the fall of shot was not broadly dispersed and, therefore, less effective. The use of the volley sights had proven generally impractical during the Boer War. The Boer commando rarely presented a suitable target, and if a British unit attempted to stand in formation to effect such fire they became a far more favourable target for the Boer riflemen. Early experience in the First World War in France and Gallipoli, where the troops soon learnt that dispersal improved survival, confirmed the Boer War experience and the volley sights were removed in late 1915 with the arrival of the SMLE Mk. III*.

The SMLE Mk. I long-range volley forward sight (left) and rear aperture sight. The volley sight was designed for wars of the past and proved generally impractical in both the Boer War and in the trenches of the First World War (AHU images).

This image shows an SMLE Mk. III from 1916 with an aperture sight fitted. In this instance the rear leaf sight has been removed, a practice which would not have been approved by the services. Aperture sights were preferred by many members of the AIF as they were in common use in rifle clubs around Australia and offered the user a sharper image of the target. While adopted for the Pattern 1914 rifle and considered for the SMLE, they were never incorporated in any of the First World War SMLE marks. A number of soldiers brought their own to Gallipoli, and some were issued in France for use on the SMLE Mk. III* in an attempt to counter German snipers (AWM REL19666).

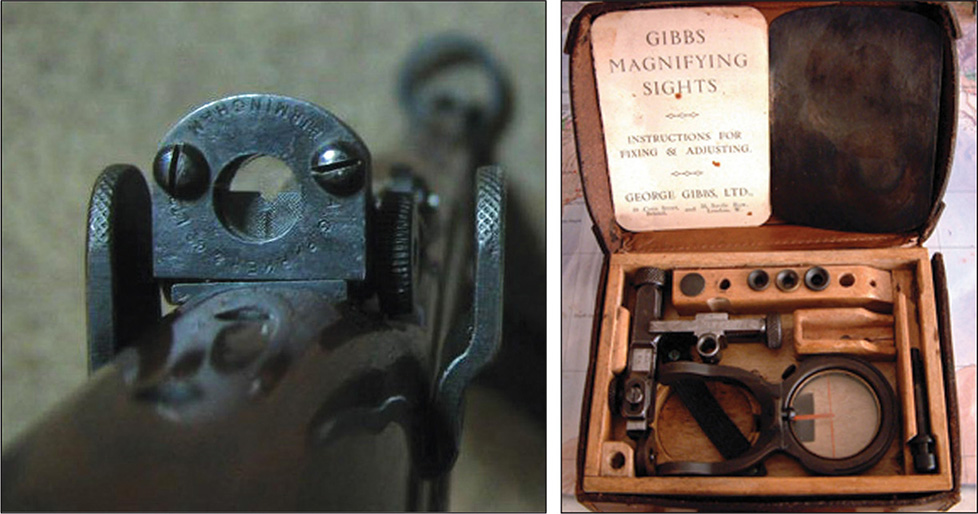

Due to the popularity of competitive shooting immediately prior to the war, numerous other types of rifle sights were trialled, tested and debated. Telescopic sights were expensive, not approved for competition shooting and, therefore, rare. However, aperture and Galilean optical sights were common. Aperture sights gave the shooter a sharper image of the target than the SMLE’s normal open or combat sights, and were approved for use in competitions in 1908. Numerous brands were available, including several from local Australian gunsmiths. While they were not an approved item of Army equipment, a number of Australians clearly took their own aperture sights with them to Gallipoli as the Official Historian, Charles Bean, commented on their use at Anzac. They were easily and quickly fitted to the SMLE and afforded the user a greater focal length and improved sight picture.

The Galilean optical sight, named after the inventor Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), was easily clipped onto the SMLE without impacting the existing open sights and operated in a similar fashion to modern, cheap, low-power binoculars often sold as children’s toys. They generally magnified the image of the target with a two-power optical view which was considered ideal for competition shooting. Unfortunately, their very limited field of vision, fragility in field conditions, impaired vision caused by moisture settling on the foresight, and the problem of a blurred target image when used on the SMLE meant that they were not particularly successful in combat. The limited field of view and blurred target image was a particular problem for the sniper as it made it very difficult to locate and track targets. Consequently, at Gallipoli most men preferred either the SMLE’s standard combat sight or aperture sights. Several versions of the optical sight were available in Australia before the war, including the Neill (also referred to as the Barnett or Ulster sight), Martin and Gibbs sights. However the Lattey sight was by far the most common. From 1916, improved versions of the Galilean sight, which were optimised for use on the SMLE, were issued to British and Commonwealth troops, primarily for counter-sniping. Approximately 75,000 of these sights were issued during the war at an average cost of between seven and eight shillings, compared with around £5 to £11 for a telescopic sight.

By the time the AIF departed Australia in 1914, a marksman equipped with an SMLE Mk. I or Mk. III rifle and .303 Mk. VI ammunition firing over open sights was expected to be able to shoot a four-inch group (101 millimetres) at 100 yards (91 metres). In other words, he was expected to place five shots within a four-inch circle on his target at 100 yards. As aperture and Galilean sights were not approved service equipment in 1914–15, there was no formal Army qualification for the use of these sights. Successful competition shooters, however, could achieve far superior results using these sights than when firing over open sights. But, as the men were to discover, conditions on a rifle range in Australia were substantially different to those experienced by the troops in combat, particularly in the theatres in which the AIF would fight its war.

The Galilean optical sights (right), as with the Lattey and Gibbs sights (left) shown in these images, consisted of two lenses, the larger of which was fixed near the foresight while the smaller lens fitted on the backsight. The Australian War Memorial holds several images of First World War SMLE rifles that were used at Gallipoli. A number of official records and soldiers’ letters also refer to their use early in the war (AHU images).