The Turks were excellent shots and sniped on the Anzacs with deadly accuracy from heights overlooking Monash Valley. They “bled” on day by day; their tally grew to grisly proportions … No one, from private to general, was safe from the sniper.

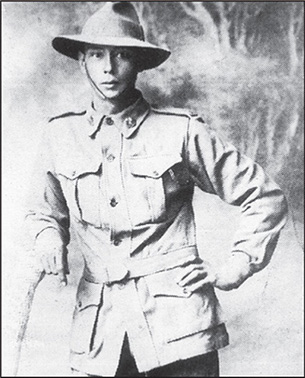

Trooper Ion Idriess, 5th Light Horse Regiment

Training in Egypt

The arrival of the Australians and New Zealanders in Egypt in December 1914 marked a period of intense administration, organisation and training. Lord Kitchener appointed Lieutenant General William Birdwood to command the troops and one of his first tasks was to organise these disparate forces into the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, later to be simply referred to as ANZAC.

According to Charles Bean, most of the Australians had received around six weeks’ training in Australia, a similar period on the voyage to Egypt and almost four months’ training following their arrival. The exception was the second Australian contingent consisting of the 4th Infantry Brigade and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade which did not arrive until late January 1915. As a consequence their training was more hurried. Training generally included subunit (section/squad, platoon/troop and company/squadron), unit (battalion/regiment) and formation (brigade) level training. Bean wrote that,

Almost from the morning of arrival training was carried out for at least eight hours, and often more, every day but Sundays. The infantry marched out early in the morning, each battalion to whatever portion of its brigade area had been assigned to it. There they split into companies. All day long, in every valley of the Sahara for miles around the Pyramids, were groups or lines of men advancing, retiring, drilling, or squatted near their piled arms listening to their officer.

Importantly, this training included extensive musketry and marksmanship practice with each battalion or regiment containing a number of qualified musketry instructors. No records remain of the number of men in each battalion who qualified as marksmen prior to their deployment to Gallipoli. Anecdotally, however, it is likely that those battalions that contained a higher proportion of country lads also held some of the best shots. Sergeant David Mortimer of the 14th Battalion, later to be employed as a sniper in France, was one of these country lads. A 24-year-old grazier from Leneva near Wodonga, a keen shooter and member of the Wodonga Rifle Club before the war, he was soon classified as a marksman after his initial musketry training and acknowledged as one of the best shots in his battalion. In the notebook he kept in 1916, he comments that almost all the ‘crack shots’ he came across were from the country areas of Australia.

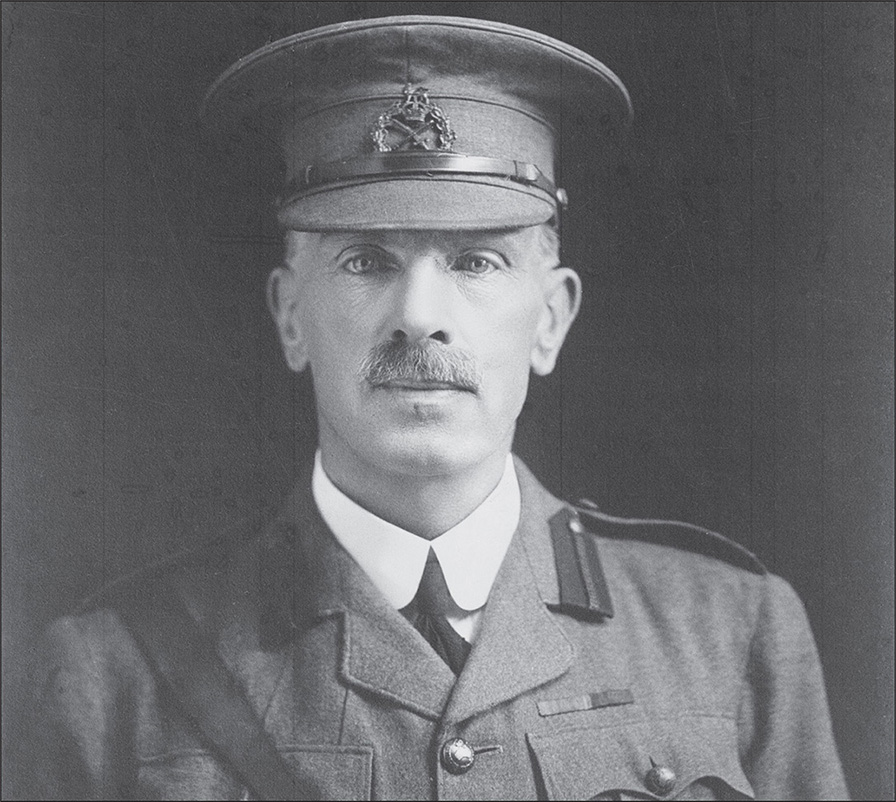

Appointed to command the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps in December 1914, Lieutenant General William Birdwood was an experienced and able officer who earned the respect of the Anzacs at Gallipoli (AWM P03717_009).

The AIF conducted extensive training in the desert before embarking for Gallipoli. In this photograph, taken in February 1915, members of an Australian machine-gun section train with their .303 inch Maxim machine-guns under the watchful eye of two machine-gun instructors, identified by the ‘MG’ badges on their sleeves. Musketry instructors wore crossed rifles above their rank on their right sleeve (AWM P01854_001).

The threat from the Turkish sniper

From the first day of the landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, soldiers’ reports and letters home often mention the ability and accuracy of the Turkish sniper. Certainly the Turkish rifleman surprised and impressed the Australians with his excellent shooting. As Trooper Ion Idriess wrote in his diary, ‘no one was safe from the [Turkish] sniper’. A number of Australians fell to Turkish fire even before they had disembarked from their landing boats. Others were shot by Turks either hiding in the scrub around the landing sites or on the high ground above the beaches. Lance Corporal Clarence Stillman of the 5th Battalion, in a letter home to his mother, wrote that ‘The chief danger of the Australians comes from snipers. These were there in hundreds. Some had holes dug under bushes and fired at Australians as they went past. Some were in trees, and these were the worst of all.’ (The Argus, 1 November 1915.)

This reference to ‘snipers’ by the Anzacs generally referred to ordinary Turkish infantry rather than the specialist that we associate with the term today. However, the Turkish Army did employ some specialist snipers before the concept was accepted by either the British or Anzac forces. A large percentage of the Turkish infantry facing the Anzacs was recruited from country areas, many from around the Gallipoli region. Predominantly farmers, these men were often good hunters, used to handling a rifle and were excellent shots. During their basic training the best shots were often identified and formed into sniper sections by their parent battalions. While the precise organisation, training and operation of these Turkish snipers is unclear, one assumption is that, as the Turkish Army’s structure and training was heavily influenced by German experience and doctrine, Turkish Army snipers were organised along German Army lines which, by 1915, included 24 snipers in each infantry battalion. The Turkish sniper was also provided additional marksmanship training, often by German non-commissioned officers. This training, while basic compared to that of the German sniper, included the use of camouflage and hides (sniper positions), stalking, range estimation and shooting. As these men used the standard infantry Mauser rifle without optical devices, they were trained to fire accurately to around 400 metres and were often afforded freedom of movement throughout their battalion’s area of operations.

Major General Bridges raised the AIF and commanded the 1st Australian Division at Gallipoli. He was killed by a Turkish sniper early in the campaign and became the only Australian killed in the First World War to have his remains returned to Australia. He is buried at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, in Canberra (AWM A02867).

Both private soldiers and officers, even senior officers, were equally vulnerable to the Turkish sniper. Lieutenant Colonel Lancelot Clarke, Commanding Officer of the 12th Battalion, was ‘killed by a sniper’ within hours of the landing. Colonel Henry MacLaurin, Commander of the 1st Brigade, was also ‘shot and killed by a Turk sniper’ on 27 April, his Brigade Major, Major Irvine, having been killed in similar fashion only ten minutes earlier. The highest ranking Australian casualty of a Turkish sniper was the Commander of the Australian 1st Division, Major General William Throsby Bridges. On 15 May, General Bridges and several of his officers were walking up Shrapnel Gulley towards General Chauvel’s headquarters. On the way they met an officer who warned them ‘Be careful of the next corner, sir. I have lost five men there to-day – a sniper!’ Running between sandbag barriers that were specifically built as protection against enemy snipers, Bridges was hit in the thigh by an enemy bullet which punctured his femoral artery. He died three days later and became the only Australian killed in the First World War to have his remains returned to Australia. He is buried at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, in Canberra.

So highly skilled was the Turkish sniper that some Australians were shot through the very small apertures in the Anzac loopholes, an opening that measured a mere 15 x 10 centimetres. Captain Corley, a well-liked and respected officer of the 11th Battalion, was reportedly shot as he passed one of the battalion’s loopholes on 17 September. At the same spot just a few days later, Private Camden was also hit, although he was more fortunate than Captain Corley and lived to tell the tale.

The danger from Turkish snipers was not restricted to the front line. Many of the rear areas, including most of the beaches, were under Turkish observation. Private Herbert Reynolds of the 1st Field Ambulance wrote in his diary on 21 June 1915:

The enemy snipers who have been enfilading Brighton beach with rifle fire have been very active lately and have succeeded in wounding half a dozen during the last few days. The range at which they have to fire makes accurate shooting impossible, but never the less they manage to bag an occasional victim and make the beach unsafe while they are at it.

Few Turkish snipers survived capture at Anzac. This enemy sniper appears to be hooded as he is led to the prisoner-of-war cage on the beach (AWM P01094_002).

In the first few weeks following the landing Turkish riflemen dominated no man’s land and the valleys and gullies used to supply the Anzac front line. They appeared to fire into Anzac’s rear areas with impunity. Soldiers even removed the wire hoop inside the caps they were issued in Egypt to flatten them, as they thought they were providing the Turkish snipers with an easy target.

Numerous diaries and letters from the Anzac soldiers describe the toll the Turks were taking on their mates. Trooper Ion Idriess wrote in his diary:

26 May. Snipers shot fifteen Aussies this morning …

29 May. The Turks have a small trench up there [above Monash Valley] which commands our road. Their trench is filled with snipers, splendid shots, who have killed hundreds of our men on this road.

28 May. Snipers got fifteen … It’s wrenched to think of so many men getting killed and maimed when they are not in the firing line.

Another light horseman, Sergeant Francis Godlee, noted in his diary for 13 May that Turkish snipers accounted for ‘10 of our 3 LH [3rd Light Horse Regiment] pals’. On 15 May he wrote, ‘This morning Turkish snipers were very severe on our chaps there were about a dozen wounded severely.’

Charles Bean recorded in his Official History that, in the first few weeks at Anzac, Turkish riflemen managed to penetrate the Australian and New Zealand positions after every attack. During a strong enemy assault on 1 May he wrote:

[an enemy party] crept along the side of Russell’s Top into the large bare watercourse … in the heart of the Australian position. Individual snipers probably stole even further, and men on the slopes in the rear of the line in Monash Valley were still shot dead from behind. The snipers were sometimes found and ki1led. As late as May 1st parties were sent to clear them out with the bayonet. But even with Russell’s Top free of them, the Turks on The Nek and the Chessboard still looked into the back of the line from Quinn’s to MacLaurin’s Hill, while those upon Dead Man’s Ridge stared at point-blank range down the valley.

Bean cites a report from the Commanding Officer of the 3rd Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel E.S. Brown, who ‘affirmed that one such sniper was found to be a Turk in civilian clothes’. Other reports mention the Turkish ‘snipers wearing Australian uniforms’ or being ‘dressed in green clothes, with face and hands stained the same colour.’ One newspaper article (The Northern Miner, 22 November 1915) describes the discovery of a Turkish sniper’s hide sited inside the Anzac perimeter, its ‘pit … found to be supplied with provisions and water … together with two thousand rounds of cartridges and three rifles’.

The Turkish soldier was initially underestimated by the British and Commonwealth forces. It was widely expected that the Turkish Army would simply run away at the sight of the Allied force massed against it. The Turkish soldier quickly proved as proficient a fighter as his Anzac opponent and, armed with his Mauser rifle, was acknowledged as an excellent marksman. The Anzacs were surprised to find in the Mehmets many of the characteristics they took pride in themselves: courage, comradeship, proficiency and marksmanship (artwork by Jeff Isaacs).

Within days of the landing it was clear that the constant threat from Turkish snipers had begun to affect the morale of the troops. Charles Bean noted that,

One sign of the strain was the seeing of spies and snipers everywhere … snipers were imagined in every gully. Most of the bullets which fell behind the lines came from the Turkish front trenches, either in sight or over the hills; but wherever a bullet fell, a sniper was suspected.

Major Richard Casey observed in his diary on 2 May that ‘Everyone has got snipers on the brain – all “overs” and stray shots come from snipers!’ Charles Bean used the term ‘sniper mania’ in his diary entry for 28 April. Contemporary newspaper articles at home, such as The Argus and The Northern Miner, referred to these ‘wild exaggerated claims of snipers’ as ‘sniperitis’.

In an attempt to counter the sniper menace, soldiers could be seen constantly ‘bush bashing’ in groups with bayonets fixed in search of hidden snipers. Others, such as Private William Greenwood of the 8th Battalion, went on ‘Jacko sniper hunts at night to capture or kill them’ — ‘Jacko’ and ‘Abdul’ were epithets the Allies gave their Turkish enemy. Another, Private William Curnow of the 16th Battalion, recalled capturing a Turkish sniper who was thought to have killed around 100 Anzacs. If a Turk was captured and suspected of being a sniper, he was generally bayoneted or shot immediately. Few were brought in for questioning, despite orders from headquarters for captured enemy soldiers to be brought in for interrogation. Private George Mitchell wrote on 7 May, ‘The Turk gets very little mercy from us. Whenever a sniper is caught he is put to the bayonet immediately.’

A few diaries held by the Australian War Memorial, such as those of William Small, a civilian merchantman, and Private Errol Devlin of the 18th Battalion, refer to the Turks employing female snipers at Anzac. While this story quickly swept through the trenches, it has never been substantiated. It was most likely one of the thousands of rumours or ‘furphys’ that continued to race the length and breadth of Anzac.

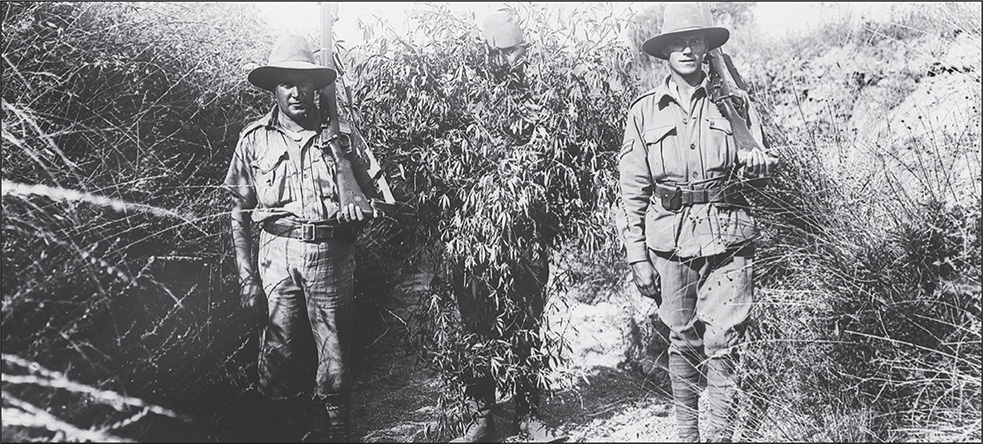

Two Anzac soldiers stand either side of a captured Turkish sniper. This scene could depict the capture of a Turkish sniper described in a letter from Private Greenwood, 8th Battalion, when he wrote ‘That Black you see in the picture was concealed in the scrub … [he] had been hiding in scrub for some time … getting a lot of our men.’ However Charles Bean described this photograph as ‘a complete fake. It was taken at Imbros. The Australians are from the Field Bakery, and the Turk is a prisoner from the camp there.’ (AWM G00377)

When the AIF was initially raised in late 1914, the establishment or structure of the force was based on the British Army’s War Establishment – 1914. This establishment did not include a position for snipers within either the infantry battalions or the light horse regiments. Both did, however, contain a platoon in each infantry battalion, or a troop in each light horse regiment, to act as the unit scouts. The scouts were considered the ‘eyes and ears’ of the unit, usually scouting ahead of the main body and reporting to unit headquarters with intelligence on enemy movements and strength, water locations and wells (primarily for the light horse) and terrain. For the landing at Gallipoli, the battalion scouts of the Covering Force (the 3rd Brigade’s 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th Battalions) were among the first ashore. Based on Boer War experience, the scouts were often country lads with excellent fieldcraft and marksman skills, and horsemanship in the light horse. Sergeant Harry Bostock, a scout with the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, wrote that ‘the scouts were bushmen with keen eyes and good shots’. At Gallipoli, while every man who was a good shot was often described as a sniper, sharpshooter or marksman, it was the scouts who formed the initial cadre of what we would later refer to as snipers, and these men were soon serving in a vital counter-sniping role.

By June it was generally accepted that action had to be taken to address the problem posed by Turkish snipers. Both Shrapnel Gully and Monash Valley, the key ‘highways’ at Anzac for the movement of supplies and reinforcements to the front and the return of casualties, had become almost impossible to traverse in daylight. The origins of a plan to deal with the sniper menace are generally attributed to Lieutenant Colonel William Malone of the New Zealand Wellington Battalion. Malone and his battalion occupied a critical but precarious position at Courtney’s Post along the lip of Monash Valley. According to Charles Bean, Malone appointed a well-known sportsman in his battalion, Lieutenant Tom Grace, ‘to organise the local snipers for the purpose of subduing this fire’. So successful were Grace’s efforts that, according to Bean, a ‘few days later this officer was placed by Colonel Chauvel in charge of a detachment of picked riflemen, who were to be responsible for the general safety in Monash Valley’. Some of these men had adopted their enemy’s Mauser rifle and ammunition ‘on account of the flat trajectory’, an action that would normally have contravened regulations, but allowances were made if they produced results.

Based on the success of Grace’s snipers, Headquarters Anzac Corps ordered each of the battalions and light horse regiments across the Anzac front to duplicate Grace’s work. Unit scouts and other marksmen were selected and paired with a spotter, the latter issued with an observer’s telescope. Men used to hunting in either the Australian bush or New Zealand countryside coached others in the selection and maintenance of hides and the stalking of ‘game’. At least one newspaper at home reported that ‘All the skilled shots have been marshalled for this service, and many men whose names have figured in the prize-lists [for shooting] are now turning their knowledge to the advantage of the Empire from a more electric firing point than the King’s Prize.’ The King’s Prize was a highly prized shooting trophy. All across the Anzac position hides were chosen and sniper pairs tasked with concentrating on a short section of the enemy’s trench-line or other positions from which Turk snipers were thought to operate. Bean noted that the observer was trained to ‘detect the whirl of dust below the muzzle of the enemy’s rifle’.

Gallipoli sniper —

Trooper Alan Campbell

Australian sniper pair at Gallipoli (AWM P01531_015).

Trooper Alan Campbell was a 20-year-old grazier from Cunnamulla, Queensland, and was among the first to enlist in the AIF in December 1914. Allocated to the 2nd Light Horse Regiment (2nd LHR), he moved to Gallipoli with his unit in May 1915 and served for three months as part of a sniper team of six operating from Pope’s Post.

The 2nd LHR snipers established a series of sniper ‘possies’ in the scrub away from their main trench. These positions were located between 200 and 300 yards (183–274 metres) from the Turks’ forward trenches across The Nek, with access via dead ground from Pope’s Post. Campbell wrote:

We worked in permanent pairs with one man spotting with a telescope who directed his mate’s fire. It was marvellous how quickly we understood each other’s directions and how accurate we could control the fire of our mate. This was one good reason why our pairs were permanent, that understanding was preserved.

Each of the three pairs of snipers soon developed a routine that involved two hours on duty with four hours off, day and night. Both men in the pair alternated shooting and spotting, and usually carried spare rifles as ‘with the heavy shooting the rifle would lose its accuracy when hot’. Apart from sniping at the Turks themselves, on occasions they used their .303 rifles to destroy Turkish parapets. This became difficult when the Turks began to use concrete blocks. For this, ‘we tended to clip off the nose of our bullets, but that tended to upset the accurate flight of the bullet. As this was against the “Rules of War” we never carried such bullets about … you were likely to be shot on the spot if captured.’

After the major Allied offensive in August, Campbell and his mates were able to see, but not reach, many of the dead Australians lying out in no man’s land: ‘From our sniper possie we had a full view of those bodies. We were able to shoot many Turks, crawling on their bellies like gonnanas [sic], looting the bodies. It was good, easy shooting.’

Campbell and the other snipers were often ‘asked to try out new ideas to help shooting, particularly the telescope sights that were being invented’. Campbell used his own Galilean optical sights, brought with him from Australia, and which he later donated to the museum of the 6th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment.

Alan Campbell was wounded in a bomb blast in 1917 during the Sinai and Palestine campaign and repatriated to Australia, returning to his home state of Queensland. Post-war he was active in both state and federal politics and died in 1982.

Not all the new ‘snipers’ operated as part of an organised plan; a number of men simply took it on themselves to ‘bag a Turk’. Corporal Herbert Hitch was the 11th Battalion’s postmaster. Finding himself with some spare time in between mail runs, and being a good shot, Hitch would regularly sneak out into no man’s land early in the morning and lie in wait. Using a captured Turkish Mauser and ammunition, he would sometimes remain hidden in no man’s land for a day or two at a time. He was so successful that soon other members of the 11th Battalion were seeking his help to eliminate particularly troublesome enemy snipers.

By late June 1915, sniping and counter-sniping had become so important at Gallipoli that they were incorporated into the local commander’s tactical plan for his sector of the front, and these actions coordinated with flanking units. Sniper pairs would coordinate their activities with the battalion intelligence officer, who would advise on recent enemy sniping locations and movements. The men were relieved of all other duties and fatigues to allow them to concentrate on the task of sniping. Moving into their hides before first light each day, and watching and waiting for the enemy to make an appearance, the sniper pairs generally formed a close bond and working relationship. This tactic proved very successful, as Charles Bean describes:

Each observer lay all day with his telescope, and beside him the sniper with his rifle, watching some small area of the enemy’s trench or territory so closely that they could eventually mark the least alteration in it. … Within a few weeks the enemy’s sniping had been so completely suppressed that traffic in the valley went uninterrupted throughout the day. … Grace’s snipers, posted throughout the valley, placed a barrier as impenetrable as any earthwork between the traffic in Monash Valley and the Turks whose trenches overlooked it. Thenceforward, provided the snipers were first warned, even a convoy of mules could go to the supply depot near the head of the gully at midday without a shot being fired at it. The conditions were so reversed that, whereas the track had previously been dangerous only by day and safe by night, it now became safe by day and dangerous only after dark; for the enemy’s snipers, silenced during daylight, now laid their rifles on to certain points in the hope of catching wayfarers at night.

The success of the Anzac snipers forced the Turks to increase their use of periscopes and loopholes, which were usually protective barriers of brick or steel with a small slot cut through which a rifle extended. According to Bean, ‘whenever a Turkish periscope appeared it was immediately shot through.’ Within a few weeks easy targets for the Anzac snipers had become rare. Men were forced to resort to extreme measures to entice the Turks to fire at them. Private Baker from the British Royal Naval Division, which was for a time allocated a section of the Anzac front line, describes how, in order to locate a Turk sniper, an Australian ran the length of the forward trench with a dummy on his back. All in the trench then waited for the Turk to fire in order to spot his muzzle flash. It worked and the sniper was killed. Others took to holding up large targets for the Turks ‘to have a crack at’, thereby revealing their position to the Anzac snipers.

The sniper/observer’s telescope

The Signaller’s Telescope Mk. IV (top) as used by Australian snipers in World War I, and the Scout Regiment Telescope of World War II (image courtesy of Mr Brad Hedges).

The telescope was, and remains, a vital item of equipment for the Australian sniper. Various versions of the Signaller’s Telescope were employed by British forces in the First World War, and were replaced by the Scout Regiment Telescope during the Second World War. The latter scope was in almost continual use by the Australian Army until it was replaced in the late 1980s.

The Signaller’s Telescope, also know as the Straight Telescope, or jokingly referred to as ‘Nelson’s Scope’ by Australians, was originally based on a naval telescope (the Telescope, Admiralty Pattern) adopted for use by British signallers, and then adapted and developed by Army snipers. First issued to Australian sniper pairs at Gallipoli in 1915, the telescope’s twenty-power magnification provided the sniper and his observer with an invaluable aid to observation. It was simple to construct and operate, consisting of several metal tubes supporting optical lenses and leather grips. Although provided with a leather protective carry case, it was easily dented, making it difficult to close and carry, and it commonly fogged up in wet weather. The lenses were made of very soft glass which was easily scratched. Considering that neither the Turkish nor Australian snipers at Gallipoli were armed with telescopic sights for their rifles, the Signaller’s Telescope gave the Australians a very real edge in target spotting and identification. This remained the case on the Western Front, even though both the German and Australian snipers had, by late 1916, been issued with telescopic-sighted rifles. The German sniper preferred to operate as a ‘Lone Wolf’ (alone) with binoculars, while the Australians continued to work in pairs. A sniper pair produced better results as the evidence suggested that one man could not effectively observe and shoot at the same time. In addition, a lone sniper can rarely observe the fall of his shot, where an observer generally can, while also providing any required corrections and a degree of protection for the sniper, especially during movement. The Signaller’s Telescope was also far superior to German binoculars in identifying targets, particularly camouflaged targets.

The Scout Regiment Telescope Mk. II illustrated here was introduced into the Australian Army in late 1939. Its design was an improvement on the Signaller’s Telescope as it offered a wider field of view and was lighter. However, it remained a relatively fragile device and would fog up in the tropical areas that characterised the Pacific campaign.

The Australian Army replaced the SRT with the Swift Telescope in the 1980s. The current official Australian sniper stalking scope is the Nikon Fieldscope ED II, although both the Swarfski and Leica spotting scopes remain in service in some battalions.

News of the Anzacs’ reputation as marksmen and their success in reducing, if not eliminating the threat from the enemy snipers in their area, eventually reached General Sir Ian Hamilton, the Commander-in-Chief of Allied forces at Gallipoli. Charles Bean wrote that Hamilton promised the hapless General Stopford, Commander of the British IX Corps, ‘a hundred picked Australians, New Zealanders, and Gurkhas to keep down the Turkish snipers, who, Stopford feared, would embarrass his troops’ in his planned attack on the village of Krithia. To support Stopford’s Second Battle of Krithia during the August offensive, a number of Australian and New Zealand snipers were sent immediately to IX Corps. ‘Within two or three days this was increased to one-hundred and their assistance was greatly valued. They returned to their own units at the end of the month [August].’

Despite the success of the Anzacs’ counter-sniping tactics, the danger from Turkish snipers had not been eliminated. While snipers had been suppressed in certain areas, the Turk took every opportunity to reassert his dominance over a section of the front. During the August offensive, for example, the recently arrived 7th Gloucestershire Regiment had its officers picked off by Turkish snipers on the high ground near Chunuk Bair as the Regiment attempted to dig in. According to author and academic David Cameron in The August Offensive, ‘this rattled the raw recruits of Kitchener’s New Army, and this part of the line quickly disintegrated.’ In the build-up to and during the Allied August offensive in the Anzac area, the Turkish snipers also targeted Australian and New Zealand officers. So deadly was their fire that some regiments formed squads of ‘marksmen’ to ‘keep the Turk’s heads down’. Sergeant William Cameron’s diary relates that he was ‘placed in charge of the Regtl [9th Light Horse Regiment] Sharp Shooters’ to support the 3rd Light Horse Brigade’s attack at The Nek on 7 August.

Certainly the Turks proved as inventive as the Anzacs and adjusted their tactics to match those of their enemy. They adopted various ruses to find the position of the Anzac snipers and employed their own marksmen and snipers to kill them. For example, they displayed numerous dummy periscopes along their trenches to trick the Anzac snipers into firing. Men were positioned on the flanks to spot the enemy rifle flashes and return fire. According to Bean, some Turks even took the extreme measure of ‘standing for a moment breast high above the parapet in order to tempt the Australian and New Zealand snipers to fire and disclose themselves’.

Throughout any war, technical options are often found to solve a military problem. The First World War was no exception — nor was Gallipoli. With the front line as close as 30 metres in sections such as Quinn’s Post, and the Turks always occupying the high ground, life for the Anzacs in the trenches was literally deadly. Anyone who put his head above a trench parapet for as little as a few seconds was extremely lucky not to be shot. Obviously this made aimed and therefore accurate rifle fire very hazardous. A number of innovations assisted the Anzacs and, in turn, the Turks. The first was what became known as the periscope rifle.

one Shot KillS: A history of Australian Army Sniping The periscope sight, also referred to as the periscope rifle, was a major innovation that enabled the men to return fire without exposing themselves to the enemy’s rifle fire. While Charles Bean claimed that it was an Australian invention at Anzac, patents had been submitted in London as early as December 1914, based on initial experience on the Western Front. It is likely, however, that the Anzac version was developed independently. Little information and few ‘lessons learnt’ from the British Army’s experience on the Western Front appear to have reached Gallipoli. These images portray a periscope sight and a locally produced viewing periscope (right) (artwork by Jeff Isaacs).

Charles Bean described the first use of the periscope rifle in his diary:

On May 19th Major Blamey, going round the front trench of the Pimple during the last hours of the Turkish attack, had observed two men of the 2nd Battalion [with a wooden frame] attached to a rifle, which they were endeavouring to lay on the parapet. “An arrangement so that you can hit without being hit,” one of them explained. It was a device for aiming a rifle by means of a periscope so fixed that the upper glass looked along the sights, while the sniper gazed into the lower one. Blamey believed that the device might be valuable, and the inventor, Lance-Corporal Beech, was afterwards brought to headquarters to apply it to a number of rifles. By May 26th a factory was started on the Beach. The first periscope rifle had been taken into Quinn’s on the previous day, the man who carried it up the path remarking to the puzzled onlookers, “I’m tired of fightin’ Turks; I’m goin’ to play them at cricket.” It was tested at many posts, and at ranges up to 200 or 300 yards was found to be an accurate and deadly weapon. From that time it was constantly used by the Anzac troops wherever the trenches were close. … at Quinn’s, where previously the garrison could scarcely fire a shot by day, it helped to beat down the enemy’s sniping, so that it became possible to fire from the loop-holes and even, for a few seconds at a time, to look over the parapet.

Periscope rifles were often zeroed at the ‘factory’ at Gallipoli before they were sent forward to the line. Here one man rests the rifle on his shoulder while another makes adjustments to the lower mirror (AHU image).

The periscope rifle was also adopted by the British regiments in the south of the peninsula and by the Turks, but Bean asserts that neither made much use of the device. At Anzac it was an immediate success with literally thousands produced and used. It was not long before almost every naval vessel had been stripped of any glass that could be used to make the periscopes, with more ordered from Cairo. Stores packing boxes were used for the wooden frames of the device. Ion Idriess described using the periscope rifle when operating as a sniper, commenting on how parts of the trench were so close to the enemy that they could not use their loopholes in daylight for fear of attracting a fusillade of bullets for their trouble. The periscope rifle was ideal in these sections of the front as it was very accurate and easy to use over short distances up to around 150 metres. For longer range sniping, the periscope was often used by the observer to locate targets with the firer having to ‘snap shoot’ — adopt a firing position, locate the target and fire, all within about three seconds. While Bean claimed that the periscope rifle was invented by an Australian, Lance Corporal Beech, at Gallipoli in 1915, applications for patents had been submitted for similar devices in late 1914. It is likely, however, that Beech invented the Anzac version independently simply to fill a critical need.

Gallipoli snipers of the 5th Light Horse Regiment

Wilson and Wetherell’s 1926 publication The History of the 5th Light Horse Regiment includes a highly descriptive account of the operation of snipers in the 5th Light Horse Regiment’s area of operations at Gallipoli:

This Regiment occupied the extreme right flank on Harris Ridge, [southern sector of the Anzac line] and special attention was given to the matter of sniping and breaking in of the enemy’s loop-holes. Special men were set off as snipers, and taken off other duties to enable them to give exclusive attention to their special job. … To prevent enemy sniping, attention was given to the Turkish loop-holes. These loop-holes on our front were made of green bricks, that is, bricks unburned, but dried in the sun, about 12 in. x 8 in. x 4 in. [30cm x 20cm x 10cm]. As soon as these loop-holes were made or repaired within a distance of 400 yards, snipers were put on to them. The heads of the bullets were filed or rubbed off. Such a bullet hitting a brick would smash it to pieces. Five or six shots usually broke up the four bricks forming the loop-hole, which then collapsed and became useless. This procedure was carried on to such an extent that sometimes there was not a serviceable enemy loop-hole facing Chatham’s Post within 400 yards of that place. Special attention was also given to the Turkish periscopes. The moment they appeared they were fired on, and smashed. This smashing of loop-holes and breaking of periscopes resulted in our people being almost free from enemy snipers. It might be mentioned that this sniping could not have been carried out without the aid of the telescopes which we had constantly in use. These were the telescopes that were originally issued to the regimental signallers. Without these telescopes the enemy movement would not in most cases be seen. The following is a divisional memo. of 11th August 1915: “From captured diaries and other sources of information it is apparent that the enemy has been suffering steady losses from the fire of our snipers. Commanding and other officers will explain to the men the value of thus establishing a fire superiority and encourage continual effort.”

Trooper Ion Idriess, also of the 5th Light Horse Regiment, described sniping at Gallipoli in several diary entries:

28 May 15 – This trench sniping is intriguing. I am a crack shot, and was put on sniping. Not seeing any Turks I blazed away persistently at one of their loopholes. The invitation was presently answered. … The sandbags along the trench are all spattered with bloodstains …

29 Aug 15 – I’ve just been indulging in a duel with a Turk, shot for shot. I’d fire, and the dust would fly up against his loophole. … and his bullet would plonk into the sandbag above my loophole. Then my turn. … It was thrilling. I waited for each of my turns with every sense keyed to concert pitch, thrilled through and through. No doubt Johnny the Turk felt the same.

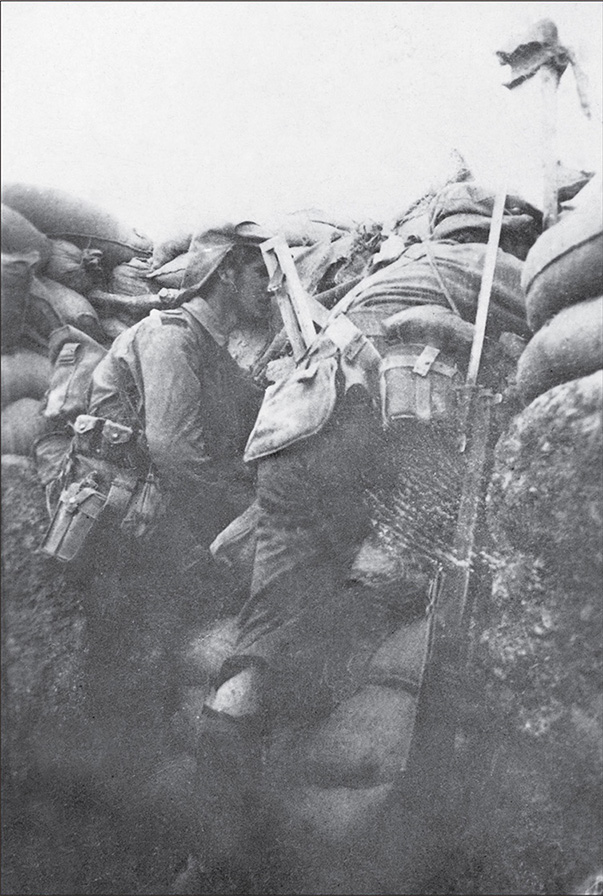

A sniper pair in action at Gallipoli in August, 1915. An observer looks through a periscope for targets while the sniper waits at the ready. Note the soft cloth caps worn by both diggers to help camouflage their position (AWM A05765).

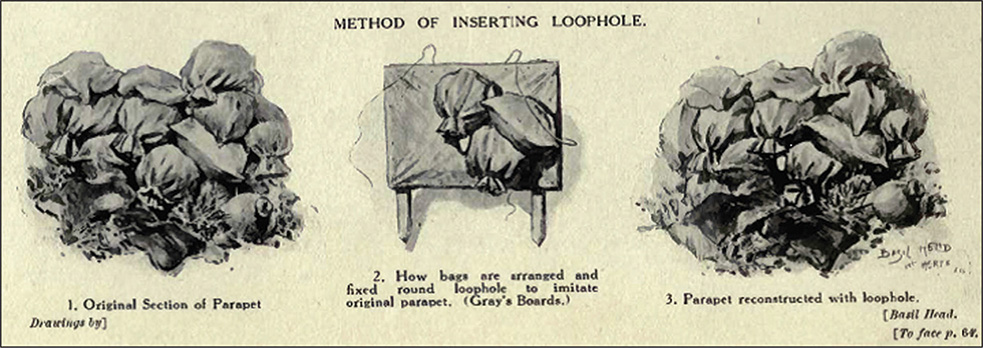

Methods of building a sniper’s loophole in a trench and concealing it from the enemy (Sniping In France by Major Hesketh-Pritchard, 1920).

A similar aid to sniping at Anzac was ‘Charley’s Wallaby Rest’. While no photograph of this device appears to have survived, the unit history of the 5th Light Horse Regiment, published in 1926, describes it in some detail. The device was the invention of Major Charley of the 6th Light Horse Regiment and consisted of a steel plate with a loophole, through which a rifle barrel protruded, and two arms to secure the rifle and allow accurate measurements to be taken, not unlike a rifle sight: ‘The idea was in the day time to register an enemy loop-hole and take notice of the lateral and horizontal graduations, then at night one could, with the aid of the register, fire at the same loop-hole, and possibly catch enemy snipers or observers.’ The unit history adds that, while ‘the principle was good’, the size of the loophole required to operate the rifle was so large that ‘the enemy’s bullets soon found their way through this large hole.’ The metal of the shield also proved too soft as ‘the enemy’s bullets perforated it like cheese. It was almost committing suicide to operate one of these machines, so not much benefit was derived from them.’

While the Anzac sniper pairs operated from a wide variety of positions or ‘possies’, often away from the forward trench-line, within the trenches it was common to find loopholes throughout each battalion’s position. These could be as simple as a protective barrier of some form, such as the cement and bricks typical of the Turkish loopholes, or the iron plates preferred by the Anzacs. Each barrier would have a hole large enough to allow a rifle to be aimed and fired. The Royal Navy supplied many of the iron or boiler plates from which the Anzacs fashioned their loopholes. Initially these were rather crude devices and offered only limited protection; the Turks soon learnt to target the actual holes in the metal plates. Since most of the Anzac trenches were so close to the enemy’s, this often made using such a device a lethal undertaking. Eventually these loopholes became far more sophisticated. Some were moved back to make them a much more difficult target for the Turk while still affording the user a level of protection and observation. Others were built into the trench-line, camouflaged and covered so that daylight would not show through when someone entered the loophole’s hide. Rules and instructions were issued regarding the use of these hides, such as who could enter, how to enter and the method of operation when inside. These rules were strictly enforced.

Australia’s most famous sniper

The most famous Australian sniper during the Gallipoli campaign, and arguably since, was Trooper W.E. (Billy) Sing of the 5th Light Horse Regiment. Nicknamed ‘The Assassin’ or ‘The Murderer’ by his regiment, Sing was a horse breaker and kangaroo and rabbit shooter from Clermont in central Queensland and a keen member of the Proserpine Rifle Club before the war. Unusual in the AIF, Sing was also part Chinese. His shooting prowess was recognised soon after his arrival at Gallipoli and he was put to sniping duties in the vicinity of Chatham’s Post at the extreme southern edge of the Anzac position. Sing’s brigade commander, Brigadier Granville Ryrie, wrote:

There is a champion sniper in the 5th regiment called Sing, he is a half bred Chinaman and has shot 119 Turks since we have been here. He lies all day and every day in a sniping position with a telescope and rifle and if they show their heads at all, he has them. He says the silly fellows will put their heads up. Between May and September 1915, Sing was credited with an official tally of one-hundred and fifty enemy killed, meaning that these ‘kills’ were confirmed by a witness. Others have put the unofficial number above two hundred. The Anzac Commander, General Birdwood, referred to Sing as his ‘pet sniper’ and remarked to Lord Kitchener that if his troops could only match the capacity of the Queensland sniper the Allied forces would soon be in Constantinople.

General Sir William Birdwood (at right with back to camera), talking to the famous Gallipoli sniper Trooper William (Billy) Sing (left) of the 5th Light Horse Regiment. Sing, nicknamed ‘The Murderer’, was reputed to have shot over 150 Turkish soldiers at Gallipoli between the months of May and September 1915 (AWM P01778_004).

Sing used a standard SMLE Mk. III, possibly fitted with an aperture sight, and usually operated with an observer. Trooper Ion Idriess was paired with Sing for a time and recorded in his diary that he ‘spotted awhile for Billy Sing this morning. … He does nothing but sniping. … He has a splendid telescope and through it I peered across at a distant loophole, just in time to see a Turkish face framed behind the loophole.’ Another of Sing’s regular observers was Trooper Tom Sheehan. Both Sheehan and Sing were wounded by a Turkish marksman when an enemy bullet passed through Sheehan’s telescope and mouth before lodging in Sing’s shoulder. His wounds saw Sheehan eventually repatriated to Australia, while Sing took a week off to recover.

Sing preferred not to restrict his activities to a single position. Several hides were established around Chatham’s Post at distances from the enemy of between 150 and 400 metres. His tried and proven method was to move into position under cover of darkness, having usually reconnoitred his position a few days before, remain very still in this hide all day, regardless of whether he fired a shot or not, returning to his unit after dark. He would always have an alternative position ready, with access via a covered route in case he felt that his location had been compromised. The unit history of the 5th Light Horse Regiment attributed Sing’s success to his ‘good eyesight and to his patience. He would remain for long periods with his eye along the sights of his rifle, whereas other men would not have the patience to do so. Sing’s operations were far in excess of those of any other member of the Regiment.’ Billy’s best confirmed tally for one day was nine.

In his book The Desert Column, Ion Idriess tells a story reminiscent of a Hollywood film, describing how Billy Sing’s reputation grew to such a point that the Turks brought in their best sniper to kill him. Sing, in the finest Hollywood tradition, promptly shot and killed his Turkish opponent. While this story is reproduced in several books, it is not verified and is likely to be an example of the mythology that often surrounds the sniper. Idriess may have been one of Australia’s better known authors after the war, but he was also known to occasionally embellish his story.

Birdwood formally recognised Billy’s prowess as a sniper when he issued an order on 23 October 1915 acknowledging Sing’s tally of 201 kills. This acceptance of the unofficial but higher score was most likely used to boost the flagging moral of the Anzac troops. Sing was later Mentioned in Despatches and awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his work at Anzac. After Gallipoli he was transferred to the 31st Infantry Battalion and moved with his new unit to France in 1916. There is some evidence that, for a time, he continued to be employed to locate and kill enemy snipers as he was recommended for a Military Medal for this work, but it was never awarded. However, he did receive the Belgian Croix de Guerre, which was probably also awarded for his work dealing with German snipers.

Billy Sing survived the war and returned to Proserpine with a new bride. But, like so many, he had a troubled post-war life plagued by alcoholism, unemployment and poverty. He died alone and almost penniless in a Brisbane boarding house in 1943.

Trooper Billy Sing is remembered today in the annual trophy for the best sniper pair in Division 1 (qualified snipers/sniper instructors) at the Australian Army Skill at Arms Meeting. In this image Lieutenant Colonel Russell Linwood, co-winner in 1988 with Sergeant Gary Ryan, presents what is now known as the Billy Sing Trophy to Sergeant Cal Hayden in 1991 (image courtesy of Russell Linwood).

Gallipoli as a sniper training ground

Trooper Sing was not the only ‘gun sniper’ at Anzac. Almost every battalion had its crack shots. Private Jim Campbell of the 20th Battalion and Private Arthur Greenwood of the 8th Battalion, for example, became renowned as snipers in their respective battalions. Lance Sergeant Percy Thurlow and Private Reg Ilett from the 22nd Battalion were regarded by their battalion mates as ‘the best of the best’ when, using a cricket analogy, it came to ‘hitting Jacko for a six’. Percy Thurlow was a former King’s Medal winner for shooting, and reputedly used a 1914 Aldis telescope on his rifle, a very rare occurrence at Gallipoli as there are no known images of telescopic sights being used during the campaign. However, Charles Bean noted that, during the period September to December 1915, ‘sniping was rendered even keener than before by the provision of telescope-rifles, magnifying sights, silencers for fitting to rifle muzzles’, and locally invented devices.

Gallipoli scout/sniper

Sergeant Wykeham

Henry ‘Harry’ Freame

Sergeant Harry Freame (AWM G01029A).

Like other exceptional Australian snipers in the First World War such as ‘Billy’ Sing and ‘Charlie’ Shang, Sergeant Harry Freame was of mixed Asian-Australian blood. Born in Osaka, Japan, in or around 1885, of an Australian father and Japanese mother, Harry was a well-educated adventurer who spoke English and Japanese and had allegedly fought in a native uprising in German East Africa in 1904 and in the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Enlisting in the AIF in 1914, he was allocated to the 1st Battalion and soon promoted to lance corporal in the battalion scouts.

Somewhat idiosyncratic, Harry became famous in his battalion for his exploits as a scout. Modifying his uniform with elbow and knee pads to aid crawling through the scrub, he also wore a brace of pistols and a small concealed pistol, carried a Bowie knife and wore a bandanna. However, he was a courageous and tenacious fighter, earning a Distinguished Conduct Medal in the early fighting at Gallipoli, with the Official Historian, Charles Bean, writing that Harry deserved the Victoria Cross. During this period he had been wounded twice, captured by the Turks and escaped by shooting his captors.

Over the next few months Harry’s fame as a scout and patrol leader increased. A 1931 edition of the Returned Servicemen’s magazine Reveille, described how Harry could:

Silently, but surely, … move about in the darkness, often up to the very brink of the enemy trench, even into it, and it is related of him that, on one occasion, he lay so close to the Turks that he could follow a game of cards in which a number of them were engaged.

He was also a sniper of some renown and could often be found manning a sniper hide on the front line. Charles Bean photographed Harry on 8 June 1915 in one of his sniper hides, commenting that ‘There are sniper’s holes looking down the valley to the north of J. [Johnston’s] Jolly. I took a couple of photos through the loopholes, and two of Freame sitting inside them.’ Bean described Freame as ‘probably the most trusted scout at Anzac’.

During the August offensive Harry was seriously wounded in the Battle of Lone Pine and eventually repatriated to Australia. In the late 1930s he was recruited as an undercover agent for the Australian government and tasked with infiltrating the Japanese community in Sydney. Later he was sent to Japan as a member of the Australian legation where Harry believed that he had been ‘found out’ and was apparently garroted by agents of Japanese military intelligence. He was admitted to a Tokyo hospital and returned to Australia, but died a few days later.

While there are no images of Turkish rifles equipped with telescopic sights, some newspaper articles mention captured enemy snipers being equipped with aiming aids. For example, an article in the Northern Miner of 22 November 1915 describes the Turkish rifles as ‘not the regulation pattern Mauser or Mannlicher, but match weapons of fine finish, fitted with every aid to accurate aim. Some had telescopic sights, and very few were without the “peep” and wind-gauge, with vernier elevation screw. One was fitted with a silencer.’ Many newspaper articles of this time contained wild exaggerations of the fighting at Gallipoli, sometimes provided by less than ethical newspaper reporters who had accompanied the troops. There is also little evidence of the Turks using anything other than the standard issue Mauser rifle. However, just as the Australians were beginning to receive improved British sights and aiming devices by late in the campaign, it is also possible that the Turks obtained optical sights — if not actual sniper rifles — from their German military suppliers.

Bean’s diary highlights the enthusiasm with which the diggers at Gallipoli took to sniping, almost treating it as a sport. Numerous instances are recorded of ‘friendly’ competition between the AIF and the Turks, including the presentation of marksmanship targets and the use of pointers to indicate a score or to ‘wave-off’ a miss. These target-shooting competitions involved the creation of a suitable target and each side taking turns to score hits. Feedback was provided as to how well the opposing side shot. Apart from the usual Bulls-eye Targets, the Australians also painted more inventive images for the Turks to shoot at, such as the face of the Kaiser or various parts of anatomy.

Men sometimes saw sniping simply as a way of relieving the boredom of trench life. Even storemen, officers and cooks would at times ‘partake in a bit of sport with Jacko across the sights of my Smelly [SMLE].’ Men such as Sergeant Brennan, a cook in the 7th Light Horse Regiment, would wander up to the line after preparing the men’s breakfast and ‘bag a few Turks’. Another soldier, Private McCowan, wrote in his diary that sniping was ‘an exciting game, far more so than football’.

While some men may have regarded sniping as a bit of a lark or a form of sport, it helped to train and prepare a generation of Anzacs for the arguably even more deadly role of sniping on the Western Front. Successful tactics were developed, such as the sniper pair, the use of the signaller’s telescope, preparation of hides and snap shooting. A brutal form of natural selection ensured that only the best snipers survived to train others and to hone the skills that would be required for survival against the German Army. It also helped to identify the qualities of a good sniper; by the time of the evacuation from Gallipoli, it was clear that a good sniper was not simply a good shot. While the sniper certainly needed a high degree of marksmanship, patience and intelligence were also regarded as essential characteristics. The surviving Gallipoli snipers formed a cadre of men who helped to refine the art of sniping in the Australian Army and who saw it develop into one of the key military specialisations that emerged during the First World War.

A day in the life of a Gallipoli sniper

A back view of a sniper, probably Lieutenant A.J. Shout of the 1st Battalion (later VC and MC), and two observers at a sandbagged post at Anzac Cove. Note the clips of cartridges and boxes near the kit bag on the right and the range card in front of the centre observer (AWM A03301).

Men officially allocated to sniping duties were normally exempted from the endless list of menial duties known as fatigues. They were also excused sentry duty due to the need for their eyesight and reflexes to be sharp for the gruelling effort of maintaining a visual vigil for long periods, either as an observer or as the firer. The daily routine of the Gallipoli sniper would have commenced the night before, when he would work fastidiously through a checklist or series of activities to prepare for the day ahead. His top priority would have been his weapon, including any secondary or spare rifle or revolver that was often taken into a sniper’s hide. These would be thoroughly cleaned and checked for damage. The barrel would be initially cleaned with oil, but then all oil would have been removed as any residue tended to generate blue-grey smoke from the muzzle when fired. Ammunition would have been inspected round by round, polished with a rag and the magazine loaded just before he headed off. Snipers would not have kept their magazine intended for sniping next day loaded overnight as this tended to weaken the magazine spring, potentially leading to stoppages. Spare rounds would have been carried, probably in the top right shirt pocket and wrapped in a clean rag so he could reach them to reload with very little movement. Usually he would have a stash of ammunition from the same production batch as it would be of a similar quality and likely to fire consistently.

Every sniper would have kept his rifle finely zeroed, and if he had any suspicion that the zero might have been ‘knocked’, he would have visited the beach to fire confirmatory groups and adjust. It is highly likely that no-one else was allowed to even touch the sniper’s rifle, except the unit armourer if he required a barrel to be changed, a sight repaired or the seer filed down or slightly polished to minimise tension during the trigger pull. He would certainly have updated his camouflage, probably using lint or a cut-up hessian bag which was also placed around the rifle to disguise its shape but not inhibit the working parts or sights. Any shine on the weapon would be dulled with shoe polish or charcoal. He would know the colour of the background earth of the hide positions he had chosen and, just before moving out before dawn, would apply that same colour to his personal camouflage. This measure was designed to reduce his chances of being spotted by Turkish binoculars or trench periscopes.

The sniper would have eaten as much as possible the night before, noting the need to cope with dysentery and the likelihood that he would not be able to eat much once deployed in the morning; in summer he certainly would not have wanted to attract any flies to his ‘possie’ which tended to interfere with observing and aiming. He might have contrived a ‘canvas’ drink container of sorts with a flexible pipe/hose similar to that used by modern soldiers with ‘back pack’ drink container and filled the night before from a reliable source of water — sometimes boiled water with a small amount of tea. Minimal movement in a hide was crucial to survival, so he would also have taken care of toiletry needs before he moved in, and if he could not, then he simply would have endured the consequences until it was safe to vacate the hide.

Snipers routinely called on their battalion intelligence officer to be allocated an area for the day’s sniping, to coordinate their efforts with the other snipers and receive a detailed briefing of known or suspected enemy sniper positions or other relevant information. Having been allocated an area, the sniper would identify several locations in which to establish his hides and the best routes for ingress and egress from each site. Most likely all of this would have occurred in collaboration with his observer. Ideally, he would not fire repeatedly from the same position, although this did occur from within trench positions or when the target opportunity necessitated.

Finally, the sniper and his observer would have retired early as they would need to be settled into their first hide well before daybreak. Their day was generally marked by lengthy periods of inactivity, interspersed with moments of extreme tension and danger. Both would be fully aware that, somewhere to their front, an enemy sniper was looking for them.