During the morning the hot sniping fire of the Germans on the plateau … continued. For its part the 6th Brigade had also sent forward nine pairs of snipers, who from allotted positions picked off the enemy, especially during the first two hours after dawn when movement was free. They claim 57 hits; word came a week or two later from Fourth Army Headquarters that German prisoners spoke of the deadliness of the Australian.

C.E.W. Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Vol. VI, The AIF in France, Chapter IV, describing a 16th Australian Infantry Brigade attack on 19 May 1918.

Germany develops a sniper force

When Germany swept into Belgium in 1914 a swift victory was anticipated. By the end of that year, however, her drive to Paris had been halted, the combatants had dug in and a seemingly interminable stalemate had developed that resulted in a series of defensive works running from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Neither side appeared to have an answer to this hiatus, although it was clear that Germany held the strategic advantage. The static nature of the front line during the winter of 1914 saw Germany in possession of over a quarter of France, much of it resource-rich and highly industrialised, and around 90% of Belgium. Arguably, Germany and her allies now only needed to hold their ground.

Germany adapted far more quickly to this new form of warfare than her enemies, Britain and France. One aspect of the German change in tactics was the employment of the largest sniper force (scharfschützen) ever deployed. These snipers, estimated at over 20,000 in number, were selected from men with hunting experience, who were then issued with telescope-equipped rifles. The principal reason for the raising of this force appears to have been to reduce their enemy’s ability and will to attack. This was to be achieved by first denying their enemy observation of the German front line by the targeting of artillery forward observers, trench periscopes and any look-outs in the forward trench-line. Second, the snipers were to disrupt their enemy’s command structure, thereby causing confusion in the enemy ranks, by specifically targeting officers and non-commissioned officers. And finally, by killing any man who stuck his head above the parapet for more than a few seconds, the German snipers would adversely affect the morale of their enemy, thereby reducing their will to attack. Deploying rifles with telescopic sights gave the Germans an ability to selectively pursue these high-value targets, particularly in poor light — an ability that neither the French nor the British troops enjoyed at this time of the war. From 1915, the German establishment for snipers was six per rifle company, or 24 in each infantry battalion. German snipers were excused from all other tasks except sniping. They were also entitled to wear a sniper’s badge of two crossed oak leaves.

This image was copied from a postcard taken from a German prisoner. Based on the German’s dress, it was possibly taken during the winter of 1915–16. The rifle is a Mauser Gew 98 sniper rifle with the scope removed. Note that the bolt handle does not stand out perpendicular to the rifle, as with a standard Gew 98, but has been bent down. This is a clear indication that it is a Mauser Scharfschützen (sniper) Gewehr 98 (AWM C02402).

The ability of Germany to field so many sophisticated rifles is often claimed to have been due to both the popularity of hunting and the foresight of the Duke of Ratibor who, at the beginning of the war, appealed to the German public for telescope-equipped hunting rifles to equip the German Army. Certainly hunting and the use of telescope-equipped hunting rifles were common in Germany before the war. For example, the number of hunting licenses on issue to the public in the State of Prussia in 1915 was estimated to be over 200,000. While the Duke of Ratibor’s campaign received wide publicity at the time and enjoyed a degree of patriotic support, it is likely that Germany’s industrial might was the main reason so many telescope-equipped rifles could be supplied so quickly to the German Army. By 1914 Germany was the leading producer of optical equipment and, therefore, telescopic sights. Companies such as Zeiss, Hensoldt and Voigtlander were producing the best hunting scopes in the world. In addition, both Germany and Austria had a long history of producing leading sporting or Jäger rifles from foremost manufacturers such as Mauser, Mannlicher, Walther and Anschütz. In 1915 the German Army was able to tap into this manufacturing capability and purchase a large number of hunting rifles from commercial dealers and even manufacturers.

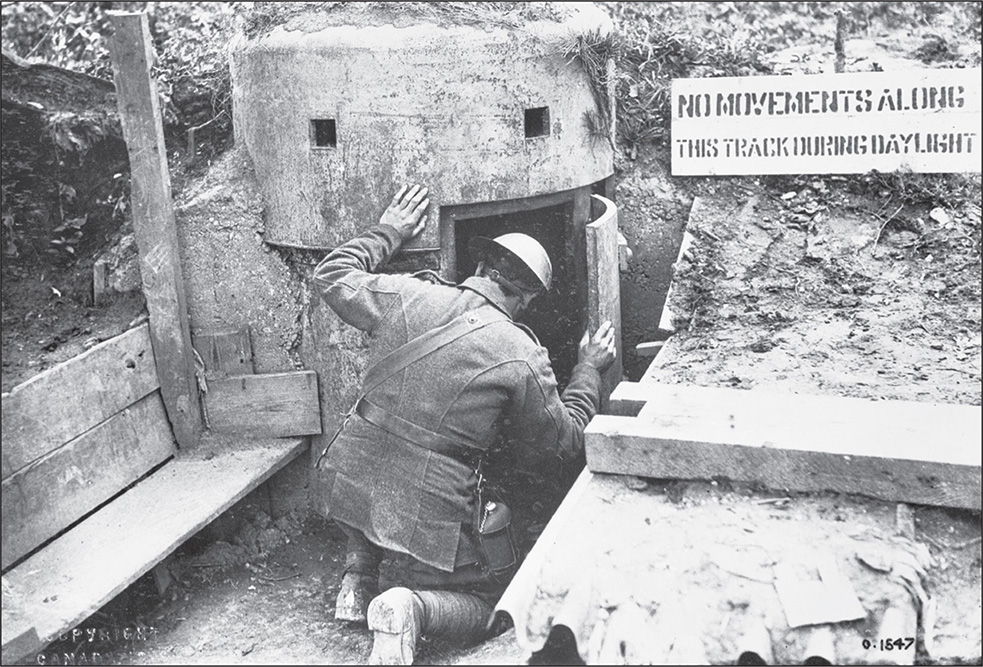

An Allied soldier inspects a recently captured German sniper’s post constructed with three-inch Krupp steel (AWM H06929).

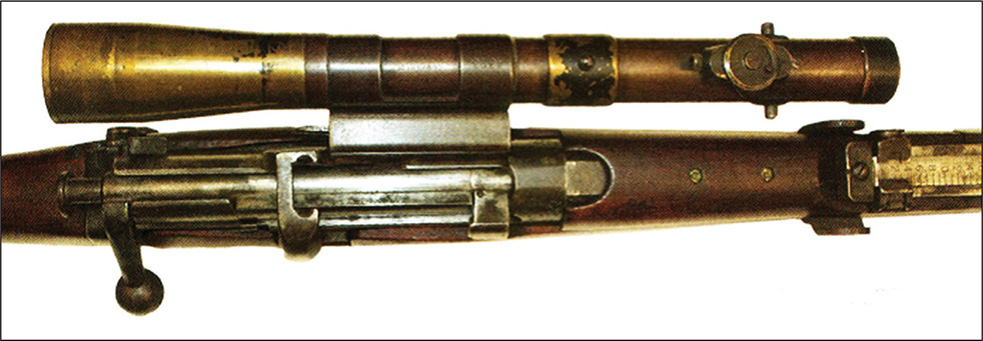

These sporting rifles were only ever considered a stop-gap measure until a standard military sniper rifle could be fielded. There were too many logistical and instructional issues associated with the very wide range of sporting rifle models and calibres in use in 1915. Again, it was the ability of the German arms industry to quickly produce a sniper variant of the infantry rifle, the Mauser Scharfschützen Gewehr 98 sniper rifle, that was to provide the edge. These rifles began to arrive at the front in late 1915 and were arguably unsurpassed for accuracy, field of view and ease of use. Rifles for sniping were selected from the manufacturer’s production line, with only those that could deliver a one minute of angle level of accuracy [that is a one-inch (25mm) group at 100 metres, two inches at 200 metres, etc] or better, selected for sniper conversion. Even without a scope attached, it is normally simple to identify a Gew 98 converted for sniper use: the bolt handle that normally protrudes at a right angle to the body is bent down in the sniper version so that it does not strike the scope when cocked, and a section of the wood removed to cater for the new position of the bolt handle.

The standard Gew 98 infantry rifle had a straight bolt handle (right), whereas the version adapted for sniper use had its bolt handle bent down to prevent it striking the telescope, and a section of the wood cut from the stock (AHU images).

The scopes were generally three or four power with a range drum on the upper body and were manufactured by a variety of commercial companies such as Ziess, Goerz, Luxor and Hensoldt. Each rifle and scope was factory-zeroed in 100-metre increments out to 1000 metres, the scope’s range drum marked accordingly and the rifle’s serial number engraved on the barrel of the scope. Both telescope and rifle were then matched and were not designed to be interchangeable with another weapon or scope. By concentrating on the Mauser Gew 98 for their sniper rifle, the Germans were able to standardise their sniper training, tactics, supply and repair systems, making the scharfschützen even more deadly.

These sniper rifles were issued to the battalion’s snipers and it was up to the sniper non-commissioned officer or Scharfschützen Gefreiter to both sign for the rifles and ensure that they were allocated to men trained in their use. Initially, the men chosen as snipers were most often those with hunting experience who possessed a level of fieldcraft, such as game wardens and forest guards. However, the pool of applicants was soon increased to include others who were not only good shots but had also proven intelligent, patient and steady under fire. In the first few months of 1915, sniper instruction was minimal, with snipers often relying on the manufacturer’s instruction booklet that accompanied the telescopic sights. By 1916 training was becoming more formal with specialist sniping schools established both behind the front and in each of the major infantry training centres, and mentors appointed in some divisions to pass on their experience to neophyte snipers.

Early in the war one of the main tactics of the German scharfschützen was to creep into no man’s land during the hours of darkness, establish a hide and wait for dawn. The telescope-equipped rifle proved particularly useful for firing in poor light such as at dawn or dusk. Allied soldiers, unaware of the use of sniping rifles by the Germans at this time, did not realise that they could be seen and would often expose themselves when repairing their parapets, collecting firewood or just moving about the trench without the usual daylight caution. Some British soldiers reported that, during dawn or dusk, even an exposed luminous watch dial was enough to attract the attention of a German sniper. Indeed, the German Army continued to emphasise shooting during dusk, dawn and at night where practicable throughout the war and developed a number of unique night-firing aids, including special ‘twilight sights’ designed to maximise available light.

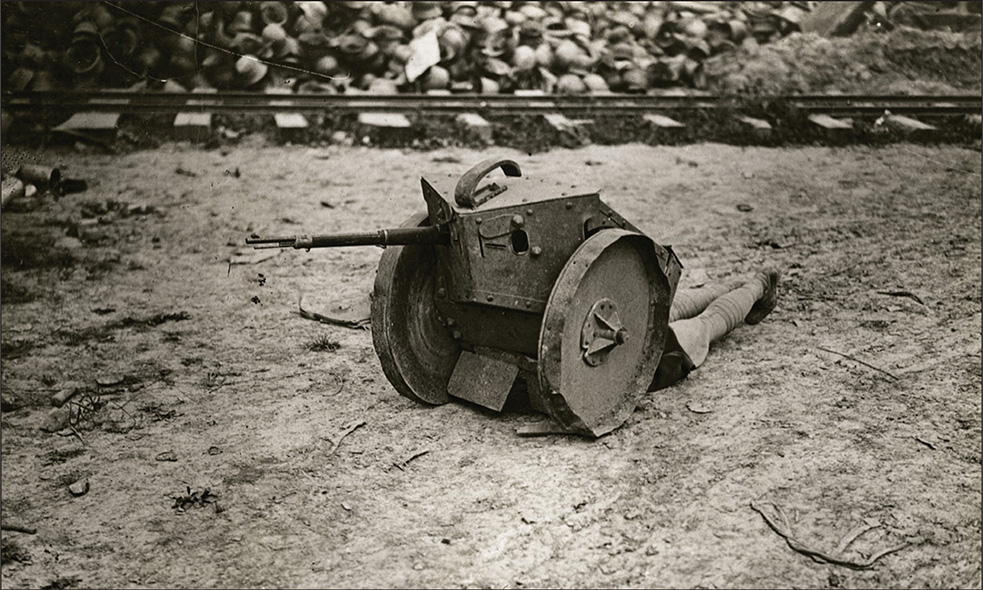

German snipers were innovative and constantly tested new equipment and tactics. Not all worked. This armoured mobile sniping post was designed to enable the sniper to move while remaining protected. Movement would have been extremely difficult in the cluttered, often muddy and uneven terrain of no man’s land (AWM H07304).

Another innovative sniper tactic adopted by the Germans was the use of a system of roving snipers. This system saw a lone sniper allocated responsibility for a section of trench, usually between 500 and 800 metres, and it was the duty of sentries in each section to identify targets for him. Later in 1915, as British counter-sniping increased in effectiveness, the Germans would deploy some of their snipers in teams of three, with one sniper supported by another on each of his flanks. This system was designed to assist in the detection of targets and enemy snipers and provide mutual support to the main sniper. During 1915 the German scharfschützen also began to use armour-piercing bullets to destroy British parapets, machine-guns and observation posts. The German armour-piercing round, known as the Spitzgeschoss mit Stahlkern (S.m.K), had a 178-grain projectile that travelled at a velocity of 2600 feet (800 metres) per second and was capable of penetrating 11 millimetres of metal plate at 100 metres. This was generally thicker than any of the loophole plates the British were using in 1915 and even during most of 1916. At the time, the British Army had access to similar ammunition.

Later in 1915, and into 1916, the British began to effectively counter the threat from the German and Austrian scharfschützens. One of the most notable features of the German sniper was his ability to quickly change tactics: as the British and French learnt to counter one approach, the scharfschützen would adopt a new method. For example, German trenches generally contained camouflaged loopholes reinforced with metal plate. As the British located these loopholes and began to use high-powered ammunition to penetrate them, more false loopholes would be constructed and increased camouflage applied to the real sniper locations which were positioned to cover these fake sites. Attracting British fire to the false loopholes afforded the German sniper the advantage; it would betray the location of the British snipers while placing the scharfschützen in a good position to return fire. While both the Turkish and Australian snipers experimented with ways to camouflage their positions and bodies at Gallipoli and during the Palestine campaign, including the use of face veils and covering exposed parts of their rifles, the Germans were the first to apply this in a systematic way on the Western Front. Their rifles were often either ‘pattern-painted’ or wrapped with strips of cloth. Various camouflage suits were trialled to better blend the sniper into his surroundings. The Germans were also first to use elaborate sniper hides such as metal tubes made to look like a tree, or deep bunkers off which several sniper positions could be developed using ingenious ruses and camouflage.

Using such tactics the German sniper proved even more lethal than his Turkish ally. An exposure of under three seconds was often enough to be fatal. In 1915 a British battalion in a relatively quiet sector could lose up to 18 men a day from enemy sniping.

Britain responds to the German sniper threat

Britain had no sniper-qualified infantry at the time war broke out in 1914, nor did the British Army possess any telescope-equipped rifles. The emphasis in the British Army remained fixed on rapid, controlled fire to ‘create a beaten zone through which nothing could live’. While experience from the Boer War exposed the British Army’s vulnerability to sniping, the lessons had not been fully appreciated and Britain deployed to France with the standard SMLE rifle and basic infantry musketry training. Soon after the Battle of the Marne in September 1914, which finally stopped the German advance and paved the way for four long years of static trench warfare, the German Army introduced its scharfschützen to the battlefield. Neither the French nor the British armies initially realised that the Germans were using telescope-equipped rifles; they had assumed that the numerous men killed by head-shots had been hit by stray rounds. By the end of 1914 the mounting toll of Allied losses and the interrogation of German prisoners provided overwhelming evidence of the use of German snipers. Nevertheless, Britain and France were slow to respond.

This John Rigby Mauser-Oberndorf commercial magnum action sporting rifle is typical of the type used by both the British and German armies in the early years of the First World War. The Mauser-Oberndorf action was arguably the most common in European sporting rifles in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, with more than 80,000 having been produced. While Rigby held the exclusive British distributorship for Mauser sporting rifles, very similar rifles were available throughout the continent. This example fires a .400/350 NITRO round, which was considered ideal for penetrating metal loophole plates. A number of these rifles found their way to both British and German trenches in 1915–16 (AHU image).

Just as the Germans had done following the Battle of Marne, the British Army eventually pressed into service numerous civilian sporting rifles fitted with telescopic sights. These included a number of privately held sporting and hunting rifles and commercially purchased rifles. Some of these were large-calibre weapons that were often referred to as either ‘elephant guns’, due to their use in hunting big game, or ‘express rifles’, named after an express train due to their large initial velocity and relatively flat trajectory. They came from a variety of manufacturers, including Purdey, Gibbs and Greener, and were available in various sizes from .600 calibre down to .400 calibre. One example is the Rigby .416 which used a solid shot. Just as the Germans had discovered, the wide variety of these civilian sporting rifles in the firing line created logistical problems with which the British ordnance system was not equipped to cope. For example, there was no repair or replacement system for damaged rifles, and these commercial rifles soon proved too fragile for trench warfare. Parts were not interchangeable and difficult to source, ammunition varied by make and model, and the scopes quickly lost focus and zero. By mid-1915, however, a small number of telescope-equipped SMLE rifles had begun to arrive at the front.

The need for snipers in the British Army was not universally accepted. Some commanders considered it ‘unsporting’ and ‘not the British way of fighting’, while others passionately supported the requirement and pushed for a formal establishment and training system for snipers. As a result, the creation, training and operation of sniping sections in the British Army in 1915 were very ad hoc. Some battalions formed sniper sections of 18 men; others had none. Several battalion commanding officers sought out men with hunting experience to train their snipers; in other units there was no training at all.

Even after the arrival of telescope-equipped rifles the British Army was initially very poorly trained or prepared for a sniper war. Rifles and scopes were often issued without any instruction or user manuals and provided to men who were not capable of understanding the more technical aspects of sniping. Official estimates indicate that six out of every ten British sniping rifles issued in this manner were rendered useless shortly afterwards. In addition, there were no sniper screens or metal loopholes, and no instruction was provided in concealment. All this meant that the early British sniper became an easy mark for the German scharfschützen.

Eventually a small sniper school was established in the Third Army early in 1915 and proved very successful, although resistance from a number of senior British officers made progress slow and ensured the Germans’ continued domination of the sniper war throughout 1915. By the time the Australians began to arrive in France from March 1916, the British were still in the early stages of organisation; most of the British Army formations had either established, or were in the process of establishing, SOS schools.

The AIF arrives in France

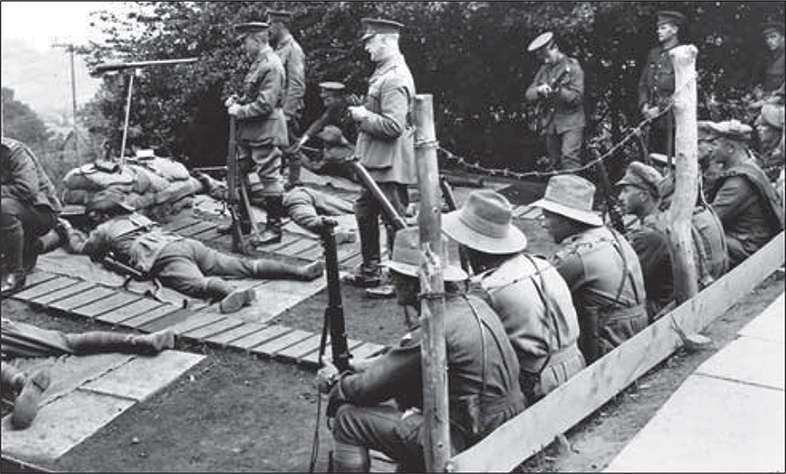

Australian soldiers at one of the British Army’s SOS courses in France (AHU image).

Prior to arriving in France in early in 1916, the AIF was substantially expanded and reorganised. Most of the infantry battalions were split in two, the resulting halves brought up to strength with recently arrived reinforcements from Australia. The 1st and 2nd Divisions and the New Zealand Division were formed into I ANZAC Corps under the command of General Birdwood, while II Anzac Corps, comprising the newly formed 4th and 5th Australian Divisions, was commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Alexander Godley. Both corps contained ‘old hands’ from Gallipoli as well as reinforcements.

Formation of the Australian sniping teams

In their first few months in France the AIF was exposed to new ideas, equipment, tactics, training and establishments based on the British Army’s experience of fighting in the trenches of the Western Front during 1914–15. Many of the Australian officers were immediately struck by the fact that the war in France was far more complicated and technical than their experience of the fighting at Gallipoli. Charles Bean noted that the war ‘had been more and more entrusted to specialists’. Sniping was no exception.

Following changes to the British Army’s establishments, each of the Australian infantry battalions formed a scout platoon under the battalion intelligence officer who was usually a senior captain. The conduct of the platoon’s training and day-to-day operations was the function of the platoon sergeant. While the platoon’s establishment was for 30 men, it was rare for this number to be available, particularly later in the war. Bean described the scout platoon as consisting of ‘expert observer snipers, and scouts, all specially chosen’, and their duties as the ‘location and subduing of enemy snipers, the location of enemy machine-guns and observing posts, general observation, and the reporting of progress or otherwise of work on the enemy’s front and support trenches.’

Sergeant David Mortimer of the 14th Battalion, shown here as a corporal, was one of the AIF’s first snipers in France. He attended the Second Army’s SOS School in June 1916, after which he commanded the scout and sniper platoon in his battalion. Sergeant Mortimer was critically wounded in the fighting around Pozières later that year and was repatriated to Australia (image courtesy of Mr Donald Leys).

Initially the members of the scout platoon, the scouts, observers and snipers, were tasked to perform three separate functions. The scouts were trained to gather intelligence and feed this back to their battalion intelligence officer. As such, they were regular members of the various patrols that would be mounted each night, particularly reconnaissance patrols. Their aim was to gain as much intelligence on the enemy as possible. Observers were equipped with a telescope and primarily supported the sniper by assisting him to locate targets and by directing his fire. A good observer was very alert to changes in his environment and able to assess their meaning. For example, a small alteration in the enemy’s parapet might indicate a new sniper hide. The sniper was the crack shot who, equipped with a sniper rifle where one was available, sought out the targets identified by the scout and located by the observer. By late 1916, these three functions had become largely interchangeable and, as the war progressed, the terms ‘sniper’, ‘scout’ and ‘observer’ usually referred to a specialist capable of all three tasks, as had already applied to the AIF in the light horse units serving in the Palestine campaign. For the first year, however, the battalion snipers came from the sniping section of the scout platoon. This section contained 18 men, broken down by rank as one sergeant section commander, one corporal second-in-command and 16 privates. With 18 men the sniper section could field up to nine sniper pairs. While this was fewer than the 24 snipers in a German standard infantry battalion, the Australian snipers could be brigaded together in larger numbers for short periods to support an attack, dominate a section of the front in a counter-sniping role, or collect intelligence on the enemy’s positions, particularly the location of machine-gun and observation posts.

Changes to the battalion’s establishment in February 1917 saw the scout platoon remain while the basic infantry platoon was now to consist of four specialist sections: one section of bombers, one section of Lewis gunners, one of rifle bombers and one of riflemen. In this last section, the riflemen were often ‘picked shots, scouts and bayonet fighters’. This changed again in 1918, when each rifle company headquarters was allocated an establishment for four scout/snipers, and ‘it was considered desirable that every [infantry] section should maintain a pair of men who had some [scout and sniping] training’.

Where the battalion held men with proven sniping ability and experience from Gallipoli, these formed the first sniper teams. Others formed their sniper section from men who had qualified as marksmen and had shown their potential in training. Gallipoli experience had proven that a good sniper was not necessarily just a good shot; patience, keen observation, fieldcraft and intelligence were also key characteristics. As for shooting, at Gallipoli some of the best snipers were also excellent snap shooters — able to identify a target and successfully engage it, all within a couple of seconds. Trooper Billy Sing excelled at snap shooting, and Australian kangaroo shooters proved to be among the best snap shooters and snipers at Anzac. On the Western Front, however, sniping was more complex. This required even the ‘old hands’ from Gallipoli to learn new tricks.

Australian sniper —

Private Caleb Shang

Private Caleb Shang, 47th Battalion (Wikipedia Commons image).

While Trooper ‘Billy’ Sing is arguably Australia’s best known sniper, another Chinese-Australian soldier from Queensland was also a celebrated First World War sniper. Caleb (Charlie) Shang, Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) and Bar, Military Medal, was born in Brisbane in 1884, the son of a Chinese father and Australian mother. Almost 32 years old, Caleb enlisted in the AIF in June 1916, arriving at his unit, the 47th Battalion, in France in March 1917, quickly learning his trade in the battles of Bullecourt, Messines, Menin Road, Polygon Wood and Passchendaele Ridge before the end of that year.

Serving as a battalion scout and sniper, Shang distinguished himself in battle, becoming one of his battalion’s most decorated soldiers. Charles Bean acknowledged Shang’s actions in mid-1917 with the following entry in his notebook:

[Shang] acted as a runner, signaller, scout, L[ewis] Gunner … He went out on patrol after snipers & got through without a scratch. Every time he came to Bn HQ he carried some information, disc or paybook. Every time he went out he carried water, ammunition and sniped in the intervals.

Shang’s citation for the DCM reads in part:

He acted as runner continuously for four days through barrages and fire-swept areas, carrying water, food and ammunition to the front line. He attacked enemy snipers in broad daylight and accounted for them. In addition to this, he constantly volunteered for dangerous patrols into enemy country, where he gained valuable information as a scout.

In April 1918 he was awarded a Bar to his DCM for ‘his wonderful powers of endurance, intrepidity and utter contempt for danger’. The citation describes how Shang volunteered to remain in an advanced observation post during a German attack while continually sniping on the enemy. The 47th Battalion’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Imlay, valued Shang’s work as a scout, including a number of his field sketches in the war diary. During the August 1918 Allied offensive Shang was wounded and evacuated to the United Kingdom. The war ended while Shang was convalescing in a British hospital and he returned to Australia later that year.

Although suffering from poor health, Caleb Shang served as a member of the Volunteer Defence Corps in Cairns during the Second World War. He died in Cairns in 1953.

Training the British/Australian sniper

While the Australians arriving in France in 1916 had a number of good shots, sporting shooters, hunters, bushmen and experienced snipers from Gallipoli among their ranks, they had not previously experienced an enemy as technologically sophisticated as the German Army. By 1916 the German sniper was experienced, trained, well equipped and knew his ground. The Australians were confident, even cocky, but had a lot to learn. It took some time for the men to realise that the German scharfschützen was different to the Turkish snipers they were used to dealing with. Where the Turk was accurate over short distances and quick to fire, the German snipers were slow to shoot, but methodical, extremely hard to detect, and deadly over extreme ranges. As the battalion diaries show, large numbers of men were killed or wounded before they could learn how to deal with this new threat. Sniper Private George Bennet of the 28th Battalion was one of Australia’s first casualties in France when he was killed in an observation post on 8 April 1916. The following month many more men fell to enemy sniper fire. The 4th Battalion’s diary for 12 and 13 May 1916 contains the following entries which highlight the danger of looking over the parapet at either dusk or dawn when the German snipers were particularly alert. Other battalion diaries contain similar entries:

May 12, 7 p.m. Private Smith shot through head while looking over parapet.

May 13. 4 a.m. Private Matthews shot through head while observing over parapet.

Even in August 1916, during their attack on Mouquet Farm, the Australians’ lack of experience in dealing with German snipers led to their assault being delayed by ‘very accurate and effective sniper fire’ which caused numerous casualties. However the Germans did not have it all their own way. According to the historian of the 21st Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment, which was deployed opposite an Australian brigade, ‘of eighteen men lost by [the] 1st Battalion between May 15th and 20th [1916] fifteen were sniped or hit by machine-guns.’

Fortunately, the AIF was initially billeted in a relatively quiet rear area which allowed the men to access the large number of British schools of instruction that had been established. These included schools for trench mortars, artillery, bombing, gas warfare, machine-guns and sniping. By early 1916, the British Army had established several SOS schools to train the new battalion sniper non-commissioned officers. The Australians were encouraged to send the sniper section commanders, usually of sergeant or corporal rank, and junior officers, particularly the battalion intelligence officer, to the SOS School. For the young officers, the course was designed more to convince them of the value of the sniper and teach them how to employ the sniper section in battle. For the non-commissioned officers the aim was to teach the art of sniping and equip them to then pass this knowledge to their sniper section. The entry requirement for the sniping schools was expressed in terms of ‘men who had proved excellent infantrymen, were of above average intelligence and education, physically fit and good marksmen’.

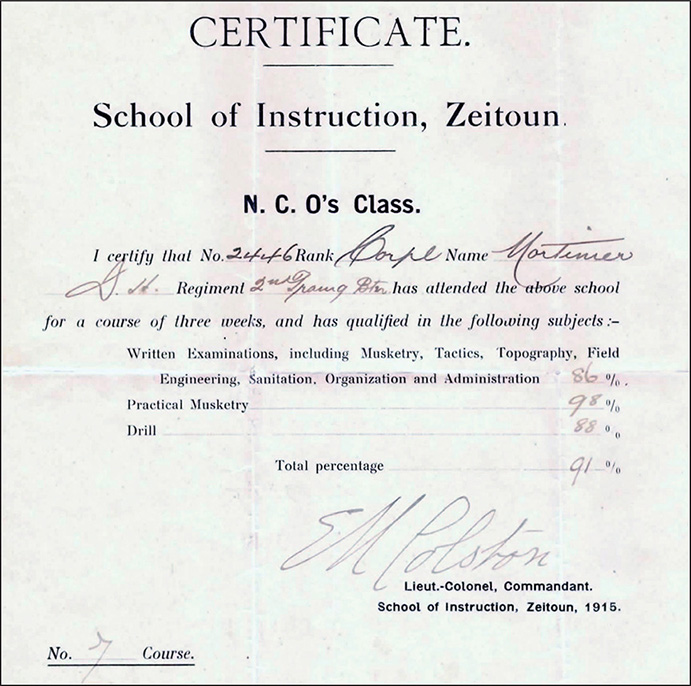

Men who had been identified as having the potential to be non-commissioned officers were often selected for attendance at the various British Army schools of instruction. Dave Mortimer’s score of 98% for ‘Practical Musketry’ earned him the marksman’s crossed rifles badge. It was probably this qualification and his promotion potential that led to his attending the Second Army’s sniper course the following year in France (image courtesy of Mr Donald Leys).

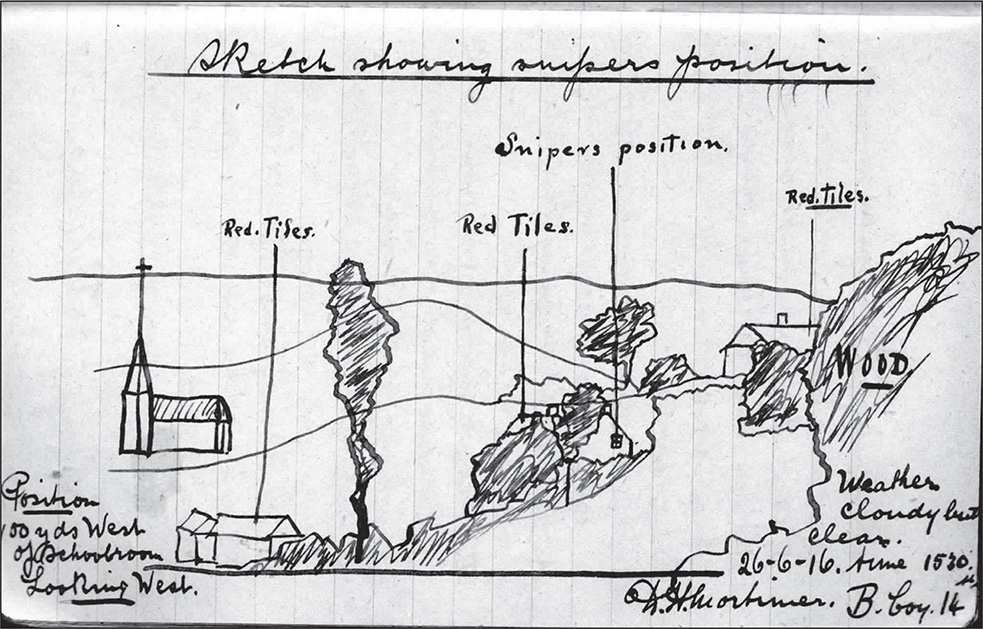

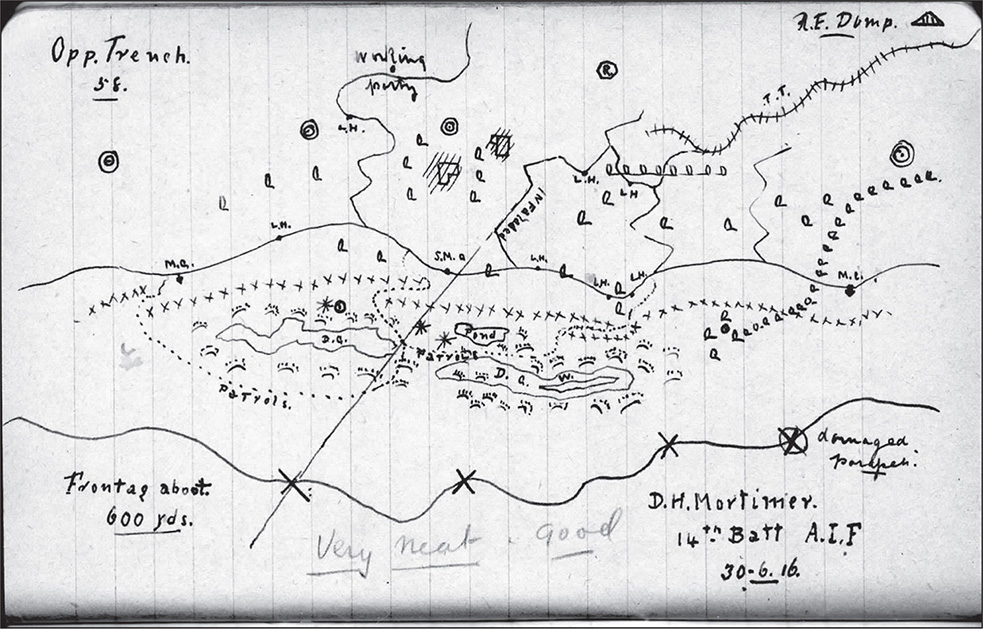

The SOS course was up to 17 days’ duration and covered marksmanship, camouflage, use of the observer’s telescope, estimation of distance, patrolling and map reading, field sketching and fieldcraft, sniper hides, intelligence-gathering and shooting under various conditions. Author and sniping historian Martin Pegler notes that the course ‘was very thorough. … Even some of the old Anzac hands, who had been snipers at Gallipoli, learnt new tricks.’ Australian snipers initially attended the Second Army schools at Acq and Mont des Cats in France. The Commandant of the Second Army Sniper School, Major Crum, who was an experienced sniper in his own right, considered the Australians ‘the best natural snipers’. When the AIF later moved to the Fourth Army, Australians also attended the Fourth Army’s sniper school.

Sergeant Dave Mortimer of the 14th Battalion was one of the AIF’s first snipers in France and among the first to receive specialised training in sniping. The 24-year-old Mortimer was an active member of the Wodonga Rifle Club which had a range close to the family farm in north-eastern Victoria. The men in the family were keen shots and Dave often trained with and competed against his brother-in-law Alf Boyes, a Queen’s Shot medal winner. Dave was also considered a good shot in his own right, having achieved a marksmanship rating at the British Army’s school of instruction in Zeitoun, Egypt, in 1915, and would have been exposed to the art of sniping during his relatively short service at Gallipoli as a corporal. Promoted to lance sergeant after the evacuation from Gallipoli at the end of 1915 when his battalion received a large number of reinforcements, he was allocated to the battalion scout platoon with one of his first tasks the creation of a sniping section for service in France. Mortimer attended the Second Army’s SOS course at Mont des Cats, France, in June 1916. His diary and detailed instructional notes provide a clear insight into the training, operations and routine of the Australian and British sniper in the First World War. Sergeant Mortimer was critically wounded while commanding his scout platoon during the fighting around Pozières in early August 1916. A shrapnel wound to his back caused paraplegia and he was repatriated to Australia early in 1917. Charles Bean makes mention of Mortimer and the action in which he was wounded in the third volume of his Official History. Mortimer eventually recovered from his wound and led a full and active life until his death in 1974.

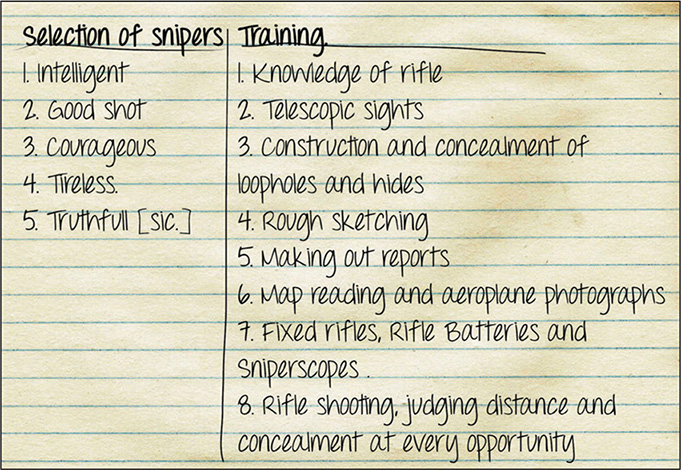

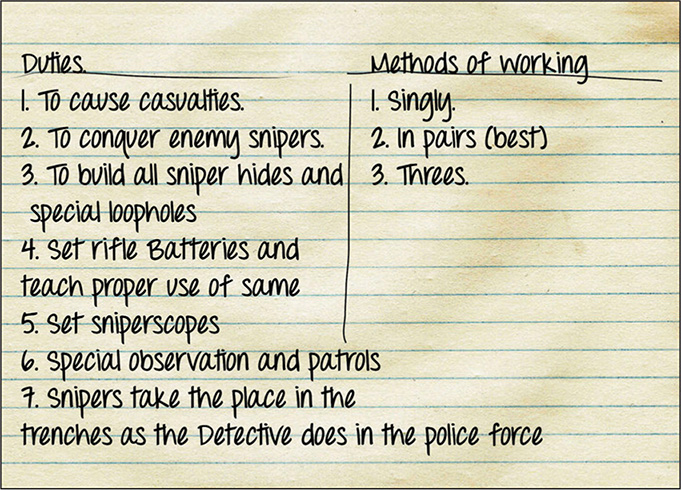

Sergeant Mortimer’s diary records what was considered the criteria for the selection and training of a sniper in 1916 (image courtesy of Mr Donald Leys).

By the end of 1916, the British sniper training, sniper experience and logistical support to the sniper were beginning to deliver results. On the Australian sections of the front, the AIF snipers were starting to dominate. By mid-1917, sniper schools were operating within every British Army area and the questioning of German prisoners showed that the enemy snipers facing the Australians tended to adopt a more cautious approach and seldom ventured into no man’s land. However, this dominance could be challenged by the Germans at any time. Private Laurence Willey of the AIF’s 46th Battalion noted in his diary in January 1917 that the fire from German snipers was very accurate and commented that the Australians seemed to be able to do very little about it. The Australians still had a lot to learn about sniping, as is evident from one battalion’s sniper selection methods. Twenty-one-year-old Private Cassim Mahomet was an Australian of Indian descent. On his arrival in France as a reinforcement for the 10th Battalion in mid-1917, he was immediately selected as a battalion sniper. In a circa 1935 edition of Reveille, the magazine of the then Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia, Private Mahomet wrote:

We ‘rainbows’ [coloured men] were lined up, and the RSM picked out two aborigines and myself. … we were detailed to become snipers. I said to the instructing corporal, ‘Why pick on me for a sniper?’ He replied, ‘All you aborigine boys have a great sense of seeing, hearing and smelling’.

A sniper post in France (AHU image).

British sniper rifles

The Australian snipers were soon issued with new SMLE Mk. III or Mk. III* rifles capable of firing the newer Mk. VII ammunition and equipped with optical sights. These sights were not all telescopic; initially a number of them were the older Lattey, Neill or Martin Galilean sights. The rifles, however, were factory tested for accuracy before being issued for use as sniper rifles. As at Gallipoli, some Australians had equipped themselves privately with commercially available peep sights used in their rifle clubs before the war, while others had telescopic sights which they fitted to their rifles. Some soldiers even used their own rifle club version of the SMLE with the permission of their commanding officers. These were retained for use in France and many of these men became the first to join the battalion sniping sections.

Recognising the limitations of the SMLE as a sniper rifle, Australian and British snipers also used captured German Mausers and, in late 1916, began to receive the British Pattern 1914 rifle. The Rifle No. 3 Mk. I* or P14 was based on the Mauser action and successfully trialled as a replacement for the SMLE before the First World War. The declaration of war saw the project shelved due to competing demands on Britain’s industry. However, by early 1915 it became obvious that a replacement for the SMLE rifle for long-range sniping was desperately needed and two American gun manufacturers, the Remington Arms Company and Winchester, produced the P14 under contract. Limited numbers of the P14 were issued to the infantry battalions, including Australian battalions, in the second half of 1916. It was highly regarded as a sniper rifle, even without a telescopic sight, which was not introduced until close to the end of the war. The P14 had a strong Mauser-style action and a heavy profile barrel with a flatter trajectory. From late 1917, some Winchester-made P14s had a fine vertical adjustment backsight fitted which was then designated the Pattern 1914 Mk. I* (F). So successful was the addition of this new rear sight that the P14 became more highly rated by snipers than the telescope-equipped SMLE sniper rifles then in service.

While the Pattern 1914 Rifle No. 3 Mk. I* or P14 was successfully trialled by the British Army prior to the First World War, competing demands on Britain’s industry from 1914 onwards precluded full-scale production. The need for a replacement for the SMLE rifle for long-range sniper fire saw limited numbers of the P14 issued to battalions, including Australian battalions, from 1916. A full sniper variant, with telescopic sights [Rifle No. 3 Mk. 1* W (T)] was not introduced until close to the end of the war (Wikimedia Commons image).

Apart from the SMLEs, P14s and Mausers used by British and Australian snipers in 1916, a number of the larger calibre sporting rifles remained in service. As armour-piercing ammunition was not available to the British Army until late in the war, these large-bore rifles proved necessary to penetrate many of the German steel sniper and observation plates, and to destroy machine-guns and some emplacements. While they were reasonably effective at this task, they were quickly nicknamed ‘suicide rifles’ as their distinctive sound and muzzle blast attracted the enemy’s attention, particularly the German artillery and trench mortars. Snipers armed with these rifles were, therefore, very unpopular with the infantry in that section of the trench-line. The ammunition used by the Australian and British snipers was standard ball; no high-grade sniper ammunition was produced. The sniper would zero his weapon whenever he received a new batch of ammunition and jealously guard his own stash.

British/Australian World War I sniper rifle

Rifle MK. III SMLE

An SMLE Mk. III rifle equipped with an Aldis No. 4 scope (AHU image).

Early in the First World War, British and Commonwealth troops were troubled by snipers and adopted various tactics in an attempt to counter what were assumed initially to be just ‘bloody good shots’. At Gallipoli, the Anzacs found themselves under intense and accurate sniper fire from the first day of the landing. However, this fire was mainly from Turkish riflemen armed with variants of the German Mauser (Models M93 and M98) fired over open sights. It was a different story when Australians began to arrive on the Western Front in early 1916. By then the German Army had developed a specialist sniper rifle, the Scharfschutzen Gewehr 98. Some Australians had equipped themselves privately with commercially available peep sights used in their rifle clubs before the war, and even a few telescopic sights, and fitted them to their standard army rifle, the Mk. III SMLE. Some soldiers even brought private rifle club SMLE rifles with them, their commanding officers turning a blind eye to the practice. But it took some time for both British and Commonwealth forces to be equipped officially with an equivalent of Germany’s Scharfschutzen.

As with Germany, Britain eventually settled on its standard infantry rifle to develop into a sniper variant. Affectionately known as the ‘Smelly’ by the Australians (after its abbreviation SMLE), it compared well to the German Mauser with its fast bolt action, larger magazine and smoother trigger action. However, unlike the Mauser, it was not designed for accurate long-range shooting. Britain also had difficulty sourcing and fitting a suitable scope, with many different variations appearing in the early years. Australians in particular disliked the scopes fitted offset to the barrel, as opposed to the German sniper rifle that was over-bore mounted. The offset scopes made it almost impossible to use most British sniper rifles in the normal trench steel loopholes as the narrow aperture significantly restricted vision. In addition, left-handed shooters found such sights virtually impossible to use. Nevertheless, as the war progressed the weapon developed into a reasonable sniper rifle, but never reached the standard of the Mauser equivalent.

During 1916 a number of the Australian snipers on the Western Front were issued with scope-mounted SMLE rifles and even captured German Mauser sniper rifles. The British government had purchased almost 3000 telescopic sights in late 1914 and early 1915. Without an optical industry as advanced as that of Germany, Britain basically procured almost anything that was available. These included German Zeiss, Goerz and Voigtlanders sights and British Watts, Aldis, Rigby, Evans and Winchester scopes, all of which were fitted to a variety of commercial and military rifles. So desperate was Britain to acquire these scopes that negotiations were opened with Germany in the hope that supplies could be secured from German manufacturers in exchange for rubber. Eventually, in late 1915, given the difficulties that had been experienced with commercial sporting rifles in the trenches, the British Army focussed on converting Mk. III and Mk. III* SMLE rifles to sniper rifles. These rifles were equipped and tested by a variety of prominent British gunmakers who fitted an assortment of telescopic sights. By late 1916, however, the various types of scopes were standardised in the Periscopic Prism Company (PPCo), Aldis Brothers and Winchester telescopes, although some Evans, Watts and Son, Gibbs, Zeiss and other telescopes remained in circulation.

Interestingly, most scopes fitted to the SMLE rifle early in the war were mounted offset to the left-hand side of the barrel. This was not necessarily unusual; a number of the German scopes were also mounted offset. However, in the German Army an offset mounted scope was more the exception, with the majority fitted in line with the rifle’s bore. In the British Army an offset mount was the norm. This was apparently due to a requirement by senior officers who were keen for the solder to be able to use the weapon’s open sights, allow charge loading (in which five rounds could be quickly loaded into the magazine from the top of the breech) and thus retain the capability to provide high-volume fire. Major Hesketh-Pritchard, a well-known sniping instructor and a leading exponent of sniping in the First World War, claimed that the decision to offset the sights on the SMLE rifle ‘shows nothing short of incredible ignorance’. He added that this decision was ‘one of the greatest difficulties’ to beset the British and Commonwealth snipers throughout the war.

This image shows a Periscopic Prism Company telescope fitted offset to an SMLE Mk. III rifle. Such a mounting was typical of British sniper rifles from 1915 to early 1918. They were awkward to use and unpopular with snipers (AHU image).

The offset scopes made it difficult for the rifle to be used in the British metal loopholes. This meant that the aperture in the plate had to be enlarged to accommodate the sniper rifle, making it easier for a German sniper to shoot through the hole. An offset scope was also impossible for a left-handed firer to use and awkward even for a right-handed shooter, as it was difficult for the firer to obtain the all-important ‘cheek-weld’ in which the firer’s cheek fits tightly into the stock of the rifle to allow a correct sight picture. Some men could only use the rifle with their left eye, an unnatural position for a right-handed firer who would normally use his right eye. After continued complaints a number of over-bore mounts were eventually made available.

Due to the large number of gunmakers contracted to fit scopes to the SMLE sniper rifle, and with each of these gunmakers using his own fittings and mounts, support and repair in the field became difficult, particularly as the various parts were generally not interchangeable. This was complicated by the fact that there was never any officially approved pattern of telescopic sight for the SMLE rifle and a number of the manufacturers produced various patterns of scopes during the First World War. For example, the Aldis Bros. telescope, probably the most popular British scope, was produced in four patterns over the course of war.

All of the scopes of this period had their limitations. Most fogged up easily, would often require adjustment after a few rounds were fired, had limited fields of view and were not always ‘soldier proof’, proving fragile in the field. Germany continued to make superior scopes throughout the war and, eventually, even Britain used a German Hensoldt Wetzler scope to design and produce the best scope of the war, the Pattern 1918. By the end of the war some 13,000 scope-equipped sniper rifles had been delivered to the British Army, including the Australians. Around 90% of these were equipped with PPCo, Aldis or Winchester telescopes. These were by no means cheap. With the average price of an SMLE rifle around £3/10, the PPCo and Aldis scopes cost about £11/10 to supply, fit and test.

Breastworks, camouflage and ruses

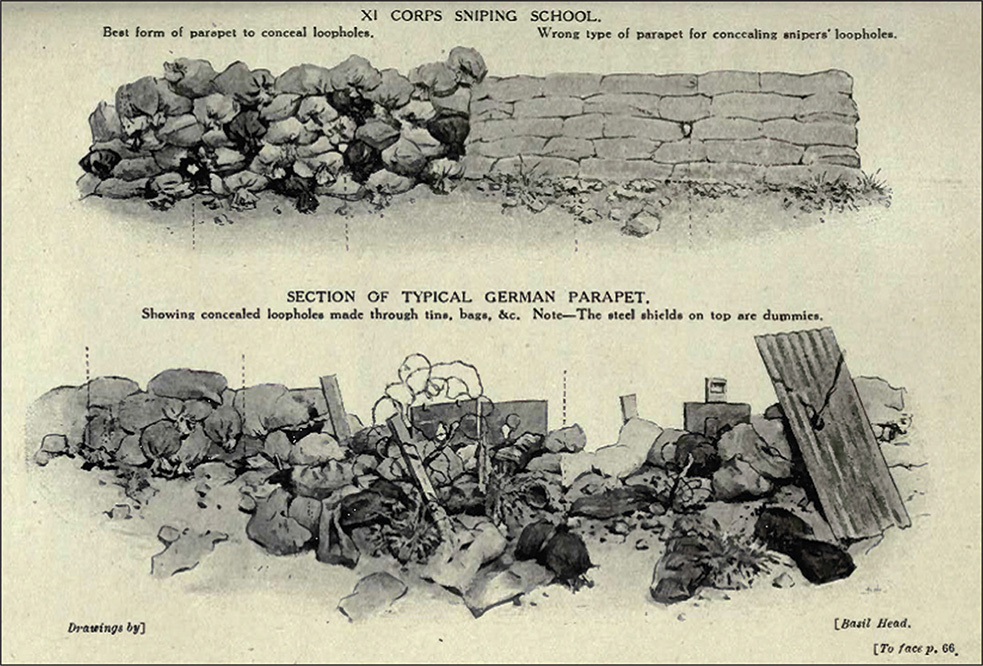

A number of Australian soldiers’ diaries from 1916 comment on how well the British trenches in France were organised and prepared. While the Kiwis were generally more fastidious in preparing, maintaining and upgrading their trenches at Gallipoli, the Australians gained a reputation for being ‘somewhat slipshod and untidy’. In comparison with the Australian trench-lines at Gallipoli, the British trenches in France were, according to historian Peter Senich, ‘marvellously neat and organised’. The apparent disorganisation of the German trench-line was viewed with disdain by the British soldier. It appeared a mess of old tin and limber, sporadically reinforced with sandbags and earth works. They were soon to learn that that this apparent ‘disorganisation’ was simply a means of hiding sniper loopholes and trench observation posts. The clean, straight lines of the British parapets tended to highlight any movement to the enemy and made locating the British loopholes an easy task.

In 1916 British trenches and parapets were well organised, neat and tidy (top right). However, these were the worst type of parapets for the hiding of sniper loopholes. Over time they looked more like the example at top left, but rarely met the standard achieved by the Germans (bottom image) in the degree of ‘planned disorganisation’ of their parapets (Sniping in France by Major Hesketh-Pritchard).

The Australians, never the neatest troops in the trench-line, saw the value in presenting a disorganised parapet to their enemy. This was reinforced as Australian officers and marksmen returned from the British Army’s SOS courses. Over time, the Australian parapets came to resemble those of the Germans, complete with hidden loopholes and sniper and observation posts. As the Australians and British became expert at hiding their sniper locations and locating German positions, so the Germans changed their trench-lines. German sniper loopholes were positioned deeper into their parapets, making them more difficult to locate, and were often sited in enfilade with interlocking arcs of fire with other such loopholes. So difficult did it become to locate German snipers by late 1916, that the British and Australians were forced to resort to various ruses to trick the German snipers into firing.

One innovative ruse employed to detect a German sniper’s location was to raise a lifelike dummy head on a stake that had measurements marked on it. When the German sniper’s bullet struck the head it would leave two holes — an entry and exit hole. Placing a stick through the two holes and using the marked stakes to determine height, it was possible to ascertain the location of the sniper. Some even gave the dummy a lifelike appearance by placing a cigarette in the dummy’s mouth and smoking it through a rubber tube. This proved very effective with one trial of the use of dummy heads in the First Army’s area of operations in 1916, when 67 German snipers were located. Factories were soon established in France for the production of lifelike papier-mache heads. So successful was this system that the Germans began to imitate it.

Men of the Australian 53rd Battalion waiting to go into action at Fromelles in July 1916. Note the straight lines of the trench’s parapet and its relatively neat appearance (AWM A03042).

Both sides went to some effort to disguise their sniper positions while exposing those of their enemy. Here a British counter-sniping team attempts to attract German sniper fire by using a lifelike dummy head (Sniping in France).

As soon as one side developed a system to locate an enemy sniper’s location, conceal their own positions or protect a sniper, counter-systems emerged. For example, loopholes were initially very primitive, comprising little more than an opening in the trench wall or parapet through which to fire a rifle. As these sites became compromised, the actual loopholes were covered with a sandbag, wood or other material, the area behind it cordoned off with a blanket, not unlike a simple photographer’s dark room, and the whole area camouflaged. This was designed to prevent the enemy locating the position by detecting either light shining through the loophole or a shadow cast over the loophole by a rifleman moving behind it. Metal plates were included to afford a level of protection to the sniper, with these plates progressively increased in thickness as the British used their high-powered sporting rifles to defeat the German plates, and the Germans in turn used armour-piercing ammunition, and even their 13 mm Mauser anti-tank rifle or T-Gewehr for the same purpose. Some snipers were known to establish sniper possies behind dead men and animals, or in camouflaged metal stands made to look like trees, destroyed buildings behind the front line or even a horse’s hide stuffed with straw.

Sniper posts established in the trenches had strict rules governing entry and use. A cover or blanket was used to prevent light shining through the actual loophole, thereby betraying the sniper’s position (Sniping in France).

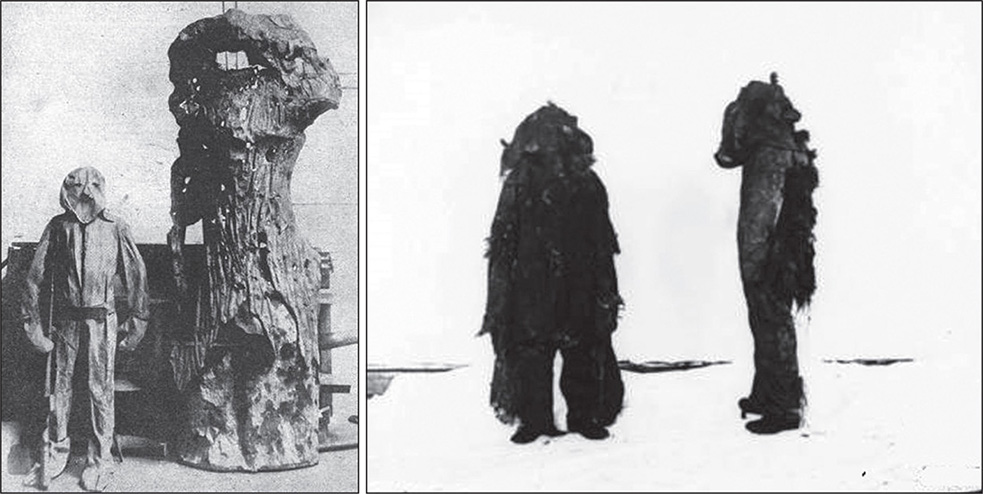

In addition to moving sniper hides and loopholes and using various ruses, both sides also developed camouflage suits for their snipers and other forms of concealment. The idea was to enable the sniper to blend more effectively into his environment by breaking up the ‘five S’ of camouflage: shape, shine, shadow, silhouette and spacing. The Germans were the first to systematically employ camouflage suits for their snipers, which generally consisted of a large overcoat with strips of cloth attached. A hood, gloves and netting covered the face and exposed parts of the sniper’s rifle. Numerous variations existed, some made of canvas, boiler suits or simple netting and even painted hessian.

The British Army’s Lovat Scouts, consisting mainly of Scottish Highlanders, had employed a camouflage suit known as a ‘ghillie suit’ since their formation during the Boer War. A ‘ghillie’ was a Gaelic word for someone who assisted in a hunt, and the ghillie suit had been developed and used by Scottish gamekeepers as an aid to hunting since the eighteenth century. There was no set form for the ghillie suit. Some were relatively simple devices made from hessian, burlap and sacking. Others incorporated local vegetation and scrim, similar to that used to cover artillery positions. However, these ghillie suits were not widely used throughout the British Army, even after manufactured specialist sniper clothing such as the Symien sniper suit became available from stores from around 1917.

As was discovered at Gallipoli, enemy sniping in France could have a devastating effect on the troops. Apart from the obvious cost in casualties, other problems included a loss of morale, limitations on movement and observation and, according to at least one soldier’s diary, a sense of being ‘under siege with no bloody way of responding’. Charles Bean observed that the scout platoon in each of the Australian infantry battalions was exempt from normal fatigue duties, a range of additional tasks soldiers performed in addition to fighting, such as repairing and digging trenches and bunkers, ferrying supplies to the front and forming various other work parties. Bean described the scout platoon as consisting of ‘expert observer snipers, and scouts, all specially chosen’, and listed their duties as ‘the location and subduing of enemy snipers, the location of enemy machine-guns and observing posts, general observation, and the reporting of progress or otherwise of work on the enemy’s front and support trenches.’ Sergeant Mortimer noted both the sniper’s duties and the various methods of deploying snipers as follows:

(image courtesy of Mr Donald Leys).

Initially the killing of enemy snipers was the most important task and also the most dangerous. As the British and other Commonwealth Army snipers began to achieve a level of parity across no man’s land, the location and destruction of machine-gun posts and artillery observers was deemed of equal importance, particularly in the period prior to an Allied attack. The killing of machine-gun crews proved very difficult as they were generally well protected behind thick steel loopholes. It was easier to aim at the machine-gun itself, although the SMLE’s .303 calibre round did not have the penetration power to completely destroy the weapons and the Germans seemed able to quickly repair their guns and redeploy them. Express rifles were of more benefit in piercing the loopholes and killing the machine-gun crew, but even this became difficult as the Germans increased the thickness of their plates. The introduction of armour-piercing rounds in 1918 finally gave the Allied snipers the ability to completely destroy machine-guns by targeting their breech mechanisms.

A metal ‘tree’ used as a sniper post, and ‘ghillie’ camouflage suits for snipers (Left: AHU image; right: AWM EZ0185).

The German sniper in France often operated as a ‘lone wolf’ or in conjunction with several other individual snipers to coordinate operations. Martin Pegler quotes one German sniper as commenting: ‘In the line I worked with a comrade who had binoculars, but often when I was in No Man’s Land or concealed behind the lines I worked on my own. I believed there was less risk of discovery if I worked alone.’

The Australians continued with the tried and proven method of sniper deployment that they had employed at Gallipoli, that of operating in teams of two: one spotter with telescope and one shooting. A trained observer was a critical member of the sniper team. Armed with a Signaller’s or Trench Telescope, the observer would scan a sector of the enemy’s trench-line identifying targets and changes in the enemy’s routine and environment. Having identified a target he would provide directions to the sniper next to him using pre-determined fixed points on their range card to orient the sniper. Once the sniper had fired, the observer would watch for the fall of shot and either indicate a hit or provide corrections. An experienced observer could tell if a man was hit. One sniper indicated that he always knew when a man was hit as he would fall immediately, ‘as though his knees were loosened’. Usually both sniper and observer were cross-trained so that they could share duties. Some, however, found it worked best if they maintained their separate and individual roles as, according to one sniper, ‘you formed an almost psychic bond with your mate [the observer] and could just about read his mind … we developed a kind of short-hand language to identify targets and directions, so I could get onto and fire at a target within a couple of seconds.’

A sniper on the Western Front usually engaged targets at distances of less than 200 metres. However, some were known to be able to shoot accurately out to 700 metres. There were generally three areas in which the snipers operated in the First World War. The first was the front-line trench. The majority of the Australian and German snipers fired from this point, particularly in the early days of the war. For the Australian sniper, however, the front line trench presented some difficulty as, for most of the war, the Australian trenches were generally lower than those of the Germans. This made observation of, and fire onto the German trenches more difficult, affording the enemy an advantage. The second area was no man’s land. This area was preferred by the enemy rather than the Australians. The Australian snipers only occasionally used no man’s land, for example to eliminate a high-value target. But it was generally considered too dangerous; extraction was difficult, it was easier to be located by the enemy and movement was severely limited if targeted by artillery or trench mortar fire. Some Germans used no man’s land as they preferred to fire over shorter distances.

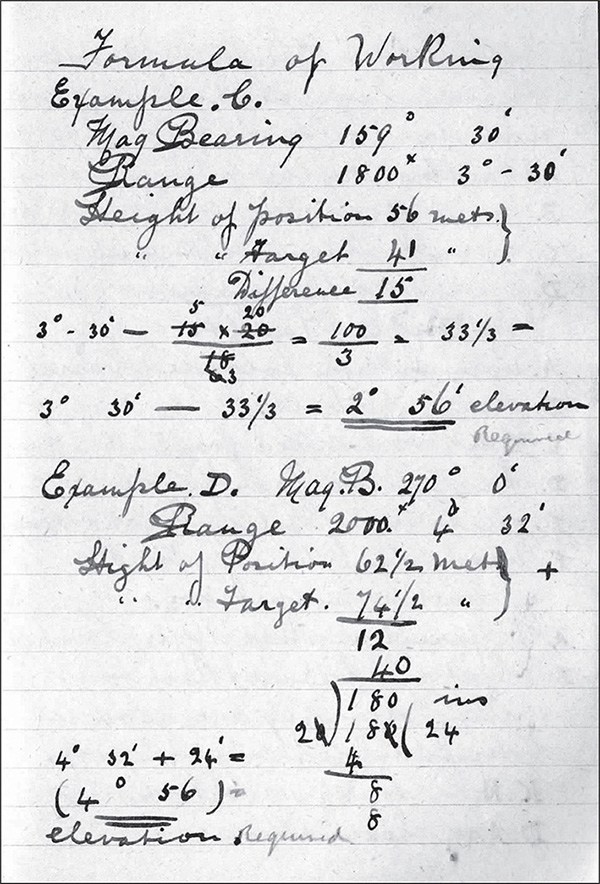

This extract from Sergeant Mortimer’s sniper course notebook includes two examples of how the sniper would calculate his ‘Formula of Working’ or what today is referred to as a Firing Solution or DOPE (Data on Previous Engagement). Often the snipers would fire onto a pre-determined target or fixed object such as a fence post or an enemy loophole, adjust their fire until they hit the target, then mark their firing solution on their range card (eg. range, elevation, wind and ammunition batch number). This would increase their chance of a first round hit at or near that target point at a later time. Men needed not only to be good shots but also possess a basic level of mathematics to pass the sniper’s course and operate as a sniper in France (image courtesy of Mr Donald Leys).

Finally, rear area positions were used, particularly by 1918 as movement became more fluid. Some veteran snipers on both sides, and others who were exceedingly good shots, would give up 100 or even 300 yards (91–274 metres) in order to gain a better field of fire and improved observation. Initially, partially destroyed buildings and even trees were used, but these proved too dangerous as they were readily noted for their potential and then easily located by enemy snipers and artillery. Usually a sniper team would prepare a position in the open during the hours of darkness and then sit it out during daylight, withdrawing that evening. Even if they had not fired a shot they would not return to the same position the next day. Routine was often the killer of the sniper.

Whatever the position used, snipers would operate from a series of hides. As they had quickly learnt at Gallipoli, a sniper who operated predominately from one location simply did not last long. Each hide had its own range card which identified key landmarks such as known or likely enemy positions, sniper hides, and observation and machine-gun posts. Where there was an opportunity to do so, a number of these landmarks were fired on and the data for a correct shot (DOPE) recorded on the range card. During night patrols of no man’s land the scouts would place distance markers, such as star pickets marked with white paint on their rear sides, or place pieces of white cloth on barbed wire to indicate wind. These too were marked on the range card, as were relevant ranges, wind and weather conditions such as the direction of the prevailing wind. It was also common for a Diary of Events to be left with the range card. This was a simple notebook which detailed such mundane events as enemy shift changes, when they threw their waste water over the parapet, the time and location of morning fires etc. All these events enabled the sniper to look for changes in the environment which might indicate a changeover of enemy battalions or preparation for an attack.

Two simple examples of range cards used by Australian snipers. Both were drawn by Sergeant Mortimer while attending his sniper course in 1916. Note the pencil remarks at the bottom of one: ‘Very Neat. Good’. These comments were from his sniper instructor (image courtesy of Mr Donald Leys).

Initially, largely due to a lack of understanding of how to best employ their snipers on the Western Front, the Australians reverted to their practice at Gallipoli and integrated the battalion’s snipers into the forward platoons or companies. However, by so doing these snipers would often be caught up in the fighting, allocated their share of fatigue duties to perform and have their area of operations restricted to that of the platoon or company. It was only through experience and the training afforded by the sniper schools, that snipers came to be recognised as a valuable resource that should be held at and tasked by battalion headquarters. This soon proved its worth as the snipers, who also became trained observers, started to pass battlefield intelligence back to the battalion intelligence officer under whom they worked. Lance Corporal Albert ‘Alby’ Lowerson, a sniper with the 21st Battalion, was recommended for a Military Medal for his ‘gallant and skillful work’ patrolling and providing intelligence ‘during operations at Armentieres and Pozieres’ where ‘his reports were valuable and reliable’. Alby did not receive this award but, as an infantry platoon sergeant in 1918, he received a Victoria Cross for his work during the 21st Battalion’s attack at Mont St Quentin.

The intelligence provided by the sniper sections was generally low grade, such as the identity of enemy units, their movements and trench routine; visible changes in the enemy’s line; gaps in the wire; or the timing of the enemy’s rotation of companies through the rear and forward trench-lines. Together with the snippets of intelligence from the other battalion snipers, observers and patrols, a picture was constructed at brigade and divisional level that helped inform such events as the timing of trench raids and patrols and harassing artillery fire, and assisted in determining weak points against which to direct an infantry attack.

One example of the value of the intelligence afforded by the scouts is provided by Bean when describing an action in May 1918. The scouts were observing a section of enemy trench that held a headquarters’ latrine. This latrine was no longer in use due to its targeting by Australian snipers. Instead, the Germans were relieving themselves in ‘the trench, from which a bottle or tin was thrown out at intervals’. One hot, drowsy day it was noticed that no container had been thrown out for some time and a raid was instantly organised which, even in broad daylight, captured several dozen sleeping Germans.

While it took some time for commanders to determine how best to employ their snipers, eventually a clear role for these men was included in the planning for operations. In the attack snipers were commonly placed on the flanks and used to destroy enemy machine-gun, observation and command posts in support of the general attack. At the sniping schools, both the snipers and their officers were warned that sending out ‘snipers or their rifles or telescopic sights in the front wave of a frontal attack can only be wasteful.’ After a successful attack, snipers were valuable in assisting in the consolidation of the position and preparing for the inevitable counter-attack by observing and reporting any movement of enemy troops, counter-sniping, interference with enemy reinforcement and acting as guides to friendly forces.

Sergeant Lowerson, 21st Battalion, won a VC during his battalion’s action at Mont St Quentin on 1 September 1918 when he and a small group of men captured 12 enemy machine-guns and took 30 prisoners. As a lance corporal in 1916, while serving as a battalion sniper, he was recommended for a Military Medal for his observation and intelligence collection at Pozieres. Early in the Second World War he was a weapons instructor at the newly formed Guerrilla Warfare School in Victoria (AHU image).

The Australian actions in May, August and September 1918 provide excellent examples of the use of the sniper during an attack. For example, immediately after an attack by the 6th Brigade on 19 May 1918, the brigade ‘sent forward nine pairs of snipers, who from allotted positions picked off the enemy, especially during the first two hours after dawn when movement was free. They claim 57 hits; word came a week or two later from Fourth Army Headquarters that German prisoners spoke of the deadliness of the Australian shooting.’

In August that year, during their attack at Hamel, the Australian sniper sections were initially used to gather intelligence on the enemy positions, particularly the location of machine-guns and other strongpoints. Immediately prior to the attack they targeted the German machine-guns using armour-piercing ammunition. During the attack they supported the advance by outflanking strongpoints and coordinating their operations with the battalion’s Vickers machine-gun company. Together ‘their fire was of great value in conjunction with the Lewis gunners in keeping down the enemy during consolidation.’

In the defence snipers were usually allocated an area of operations across the front. Sometimes the snipers were grouped together directly under the brigade intelligence officer, such as where an enemy attack was expected. For example, during the German spring offensive between March and July 1918, the Australian snipers formed part of the brigade’s defence in depth plan. The snipers were allocated ‘zones of control’ and given as their priority task ‘to pick off the leaders, and members of machine-gun and flamenwerfer [flame-thrower] detachments’. Each pair of snipers also had alternative positions ready to enable them to snipe into their own trenches should they become occupied by the enemy — ‘they will thus be in a position to inflict heavy losses upon the new occupants’.

These tactics were largely developed through trial and error, and after many lives had been lost. In July 1916, during the Australian attack on Pozières, German snipers were a particular problem as they were well positioned in the ruined buildings of the village and proved exceptionally hard to dislodge. One enterprising platoon commander in the 9th Battalion, Lieutenant White, broke his men into a number of sniper-hunting teams which were armed with grenades and white phosphorus bombs. While White met with some success, his mounting casualties forced him to send a despatch to his battalion headquarters: ‘Am doing best but request presence of more and senior officers. Snipers are pretty bad in old buildings of Pozieres.’ He was eventually ordered to stop his advance ‘as many [of his men] were shot’. While White and his men were fighting through the village with difficulty, the snipers of the German 86th Reserve Infantry Regiment were focussed on the Australian trench mortar crews and preventing Australian reinforcements moving into the village, while others were causing casualties in the 25th Battalion. According to Bean, one of the companies of the 25th Battalion was held up by a lone sniper: ‘The men [were] cowered by an enemy sniper. The company commander, Captain R.J. Lewis, had just been shot through the brain while looking over the parapet, and the same fate had befallen the man who took his place.’

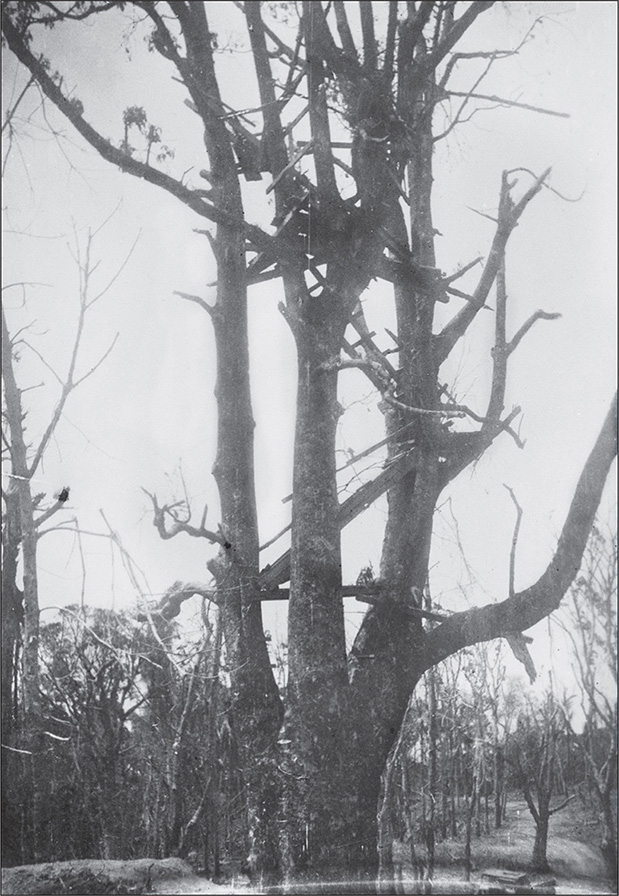

An Australian inspects a deserted sniper’s post in a tree at Retaliation Farm in the Ypres sector in October 1917. Note the duckboard path in the foreground which would have afforded ease of passage for the sniper in the muddy terrain (AWM E00953).

A number of historians have indicated that, by 1918, the Allies dominated the enemy snipers. Certainly Allied snipers could achieve a local dominance for a time; however, according to Charles Bean, the German sniper was never completely defeated, certainly not to the level of ‘mastery approaching that gained and held over the Turks in Monash Valley.’ This is evident in the battles as late as 1918. In April of that year the 2nd Australia Division moved into trenches above Dernancourt and suffered numerous casualties to German snipers. To deal with these snipers the forward two brigades, the 6th and 7th, organised their own snipers into teams, each under the command of an officer. These Australian sniping teams initially focussed on destroying the German trench periscopes to deny them observation and, within three weeks, claimed to have hit 127 enemy soldiers and made the German snipers so cautious that they rarely fired. In addition, interviews with captured Germans along the breadth of the Australian Corps front line emphasised the accuracy of the Australian sniping. The histories of the German 9th, 31st, 97th, 232nd and 265th Reserve Infantry Regiments, which held positions opposite the AIF around this time, note the problems the Australian snipers caused them by preventing any movement by day, minimising their observation of the Australian positions and reducing the effectiveness of either direct or indirect fire. In the 31st Reserve Infantry Regiment communication was reduced due to the loss of ‘our splendid dogs Else and Wolf. … The Australian snipers often caught sight of the dogs, which had to run the gauntlet of their bullets, and at least one was shot and one (at Villers-Bretonneux) captured.’

As the war continued, actual shooting took up much less time than intelligence-gathering. Apart from their sniping rifle, snipers often now also carried binoculars, telescope or trench periscope, a marked-up map or sketch of their section of the front, and also wore a revolver as a secondary arm.

First produced in 1870s by Webley & Son of Great Britain, the Webley and Scott Mk. VI revolver was adopted for British military service in 1887. It was a break-top, six shot, double action revolver, which launched a heavy (18 grams) lead bullet at relatively slow muzzle velocity (180 metres/second). The Webley revolver evolved through several marks, with the Mk. VI the standard sidearm of the British Empire forces in the First World War. It remained so for the duration of the war and was issued to officers, airmen, trench raiders, machine-gun teams, tank crews and snipers as a secondary arm. It proved a very reliable and hardy weapon, well suited to the mud and adverse conditions of trench warfare (AHU image).

The end of the First World War

By the end of the war the sniper had proven his worth on both sides of no man’s land and had evolved from an infantryman who happened to be a good shot, to a highly trained and experienced specialist within a more complex military machine than was ever imagined in 1914. As with other specialisations within the Army, including machine-gunners, bombers, tunnellers and observers, the British, German and Australian armies developed doctrine, tactics, techniques and procedures to fully integrate the sniper into their battle plans, with specific roles depending on the phase of war or the terrain encountered.

This German sniper was killed by a bullet through the neck while in the act of shooting. When discovered by the Australian official photographer, his personal kit and equipment were intact; his finger was still on the trigger, and the magazine of his rifle partly full. In a leather satchel by his side were several important papers and a letter to his wife and child written the night before. In his letter he wrote that he was positioned opposite the Australians who were terrible fighting men, who sneaked out through the grass and stole his men from their posts. He hoped he would soon be relieved and go to another sector where there were no Australians (AWM E02955).

According to the official historians and contemporary records, the Australian sniper proved equal to the task and even better than some. Major Hesketh-Pritchard, a leading British sniper advocate during the First World War, and the Commanding Officer of the 1st Army’s School of SOS, assessed the various national Army snipers as follows:

Of the Germans … with certain brilliant exceptions, they were quite sound, but rather unenterprising … the Bavarians were better than the Prussians, while some Saxon units were really first rate. … The English were sound, exceedingly unimaginative, and very apt to take the most foolish and useless risks … The Welsh were very good indeed … The Americans were also fine shots, and they thoroughly enjoyed their work … The Canadians, the Anzac and the Scottish regiments were all splendid, many units showing an aggressiveness which had the greatest effect on the morale of the enemy.

The Australian citations for awards, following British practice, do not generally identify a soldier’s specialisation. As such, it is almost impossible to determine whether snipers received awards while serving in infantry units. Three, however, stand out due to their extraordinary actions. The first is Trooper, later Private William (Billy) Sing, who was Mentioned in Despatches and awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his service as a sniper at Anzac, and the Belgian Croix de Guerre, possibly for his work in dealing with German snipers.

Another is Private Walter October Rabey, who was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal when, as a sniper in the 17th Battalion, he captured ten Germans and a machine-gun during the First Battle of Passchendaele. Finally, the only Victoria Cross attributed to an Australian sniper was awarded to Sergeant Albert Lowerson of the 21st Battalion for his actions at Mont St Quentin in September 1918. We may not be able to identify all those snipers who received formal recognition for their work, but we do know that the cost in casualties was high. While there are no records of Australian snipers killed on the Western Front as casualties are also listed by unit rather than speciality, estimates for British Army sniper casualties during 1918 are around 50%. Given that the Australian Army was integrated into the British Army throughout the war it is reasonable to expect that our casualties were at least similar.

Regardless of the good work of the Australian snipers during the First World War, most of their expertise and ‘lessons learnt’ were lost by 1939 when Australia was again at war with Germany, followed by Italy and later by Japan.