CHAPTER 6.

The Second World War

What indeed is the human animal in war but a special variety of soft-skinned dangerous game?

Lord Cottesloe, 1944

Between the wars

While the First World War saw the birth of Australian military sniping, by the 1920s the capability had effectively died. Cutbacks in military spending and a new wave of pacifist optimism meant that the art of sniping had not been maintained, nor had sniping doctrine, tactics, techniques, procedures, training or establishments. With the reorganisation of the Australian Army in 1921, the emphasis returned to the basics of soldiering and a reliance on part-time militia forces supplemented by a cadre of regular Army staff and instructors. Many of the specialist skills developed during the First World War were neglected, if not ignored altogether. Sniping was largely regarded as irrelevant, as many senior commanders in the British and, therefore, the Australian armies, considered it applicable only to static warfare, as experienced on the Western Front, and the strategic wisdom of the time was that Australia would not involve herself in such a war again.

Early sniper rifles

Fortunately, Australia continued to place priority on musketry training and, in the post-war period, took two decisions that would allow the Australian Army to eventually redevelop its sniper capability. The first was to obtain from Britain a number of Enfield Pattern 1914 (P14) sniper rifles, their correct designation Rifle No. 3 Mk. I* W (T) (the ‘W’ indicating the manufacturer, Winchester, and the ‘T’ that it was equipped with a telescopic sight). In April 1918, the P14 rifle, equipped with a Pattern 1918 scope on overbore mounts, had been approved as the British Army’s standard pattern sniper rifle. Testing showed that it could produce a 1.5-inch (3.81 cm) group at 100 yards (91.44 metres). Snipers had to achieve 3-inch (7.62 cm) groups or less at this range. Few P14s had reached the front before the end of the First World War, with most either going into storage or being offered to Dominion military forces, including Australia. It was this rifle that would become the Australian Army’s primary sniper rifle during the Second World War. A few of these rifles were also fitted with refurbished and offset Aldis or PPCo telescopes from older First World War SMLE sniper rifles still held in military stores. Few of these composite rifles survived to the war’s end due to the problems experienced in obtaining spare parts for the older scopes and the fact that the Australian soldier never favoured offset scope mounts.

British/Australian World War II

sniper rifle

Enfield Pattern 1914 [Rifle No. 3 Mk. I* W (T)]

A Pattern 1914 Enfield No. 3 Mk. I* (T) sniper rifle with a Pattern 1918 telescopic sight (AWM REL06068.001).

The shortcomings of the SMLE as a sniper rifle were well known by the time the Second World War erupted and alternatives were quickly sought. One of these was the .303 Enfield Pattern 1914 (P14), later designated Rifle No. 3 Mk. I*. An earlier version of the P14 (based on the P13) had been successfully trialled by the British Army prior to the First World War. However, Britain’s entry into the war, competing demands on its domestic industry and technical difficulties with the specialised ammunition meant that no full-scale production facility was established. Instead, Britain placed orders with three companies in the United States. Winchester was the principal supplier, using a variant of its M1917 and concepts from the P13, producing the P14 in .303 calibre. A distinguishing brass circular plate was affixed to the right side of the butt given the differences in calibre when the US Army deployed to France in 1917 with the M1917.

Compared to the SMLE, the P14 included a stronger Mauser-style action, a heavier profile barrel, longer sighting radius with a folding aperture backsight, a one-piece stock, a five-round internal magazine, and was simpler to manufacture. The new rifle proved extremely accurate and, by the end of the war, sniper variants were being produced for the British Army.

The shortage of sniper rifles in Australia at the outbreak of the Second World War saw the P14 rifle given a new lease of life. A number were stripped and rebuilt as sniper variants by the Small Arms Factory at Lithgow. These were fitted with a locally produced Pattern 1918, three-power, overbore, high claw-mount telescope and designated the Rifle Enfield No. 3 Mk. I* W (T), ‘W’ for Winchester, and ‘T’ for telescope. The P14 served as an important stop-gap measure while another sniper rifle could be developed and produced, which did not occur until late in the war. In the early years of the war, one British officer was very impressed with the Australian snipers who were using the P14, remarking that ‘these kangaroo shooters’ in the Army were ‘really remarkable shots … In Timor one of these … was credited with 47 Japanese killed, but with characteristic modesty claimed only 25 certainties, remarking: “In my game you can’t count a ’roo unless you see him drop and know exactly where to go and skin him”.’

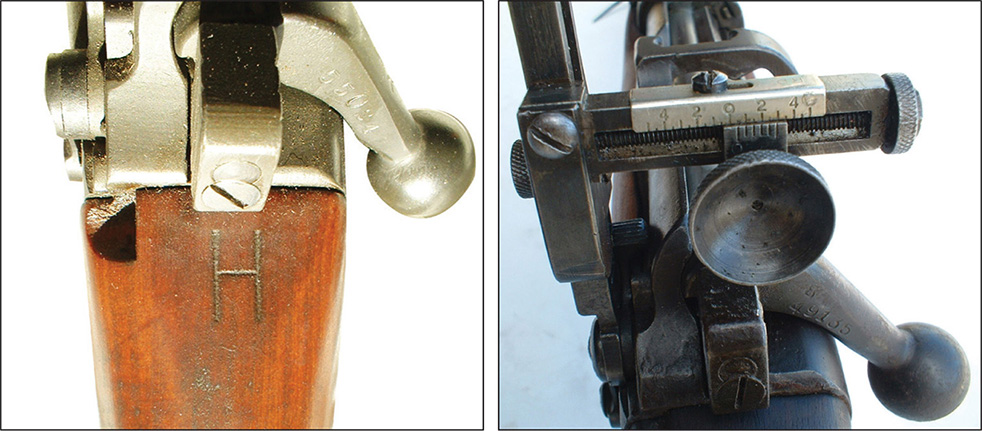

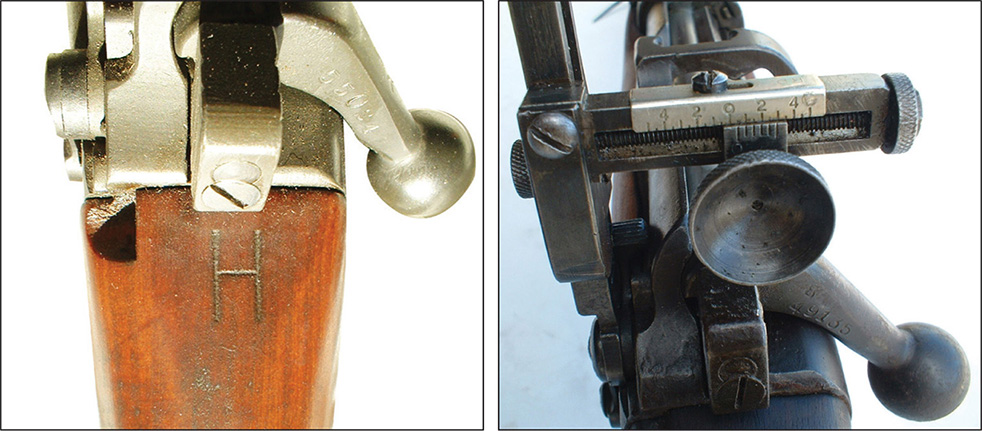

The second important decision by the Australian Army was to have the Lithgow Small Arms Factory examine options to improve the accuracy of the SMLE. The First World War had highlighted the shortcomings of the SMLE, particularly its accuracy over longer distances when compared to the German Mauser or Mauser-type actions. Lithgow had been producing the SMLE since 1913 and factory designers believed that the rifle could be improved by the fitting of a larger diameter or heavier barrel. The result was a similar profile barrel to the SMLE’s predecessor, the Long Lee or Magazine Lee-Enfield. Adapted SMLEs were marked with ‘H’ stamped into the top of the buttstock for heavy barrel, and fitted with a rear aperture sight. These sights were very popular, particularly among sporting club shooters who used them in competition matches. The most common types of aperture sights included Mues, Motty, Central and a Lithgow-made copy of the Central. These target sights generally provided improved accuracy over the standard combat or leaf sights and afforded a greater field of view than that provided by the available telescopic sights, although they were difficult to use in poor light conditions or when engaging a well-concealed target. The heavy barrel weapon’s accuracy was markedly superior to the standard SMLE Mk. III* and was an immediate success among rifle clubs across Australia. Designed more as a marksman’s rifle than a true sniping rifle, the heavy barrel SMLE was favoured by a number of Australian snipers in the Pacific campaign over telescope-equipped rifles due to its improved field of vision.

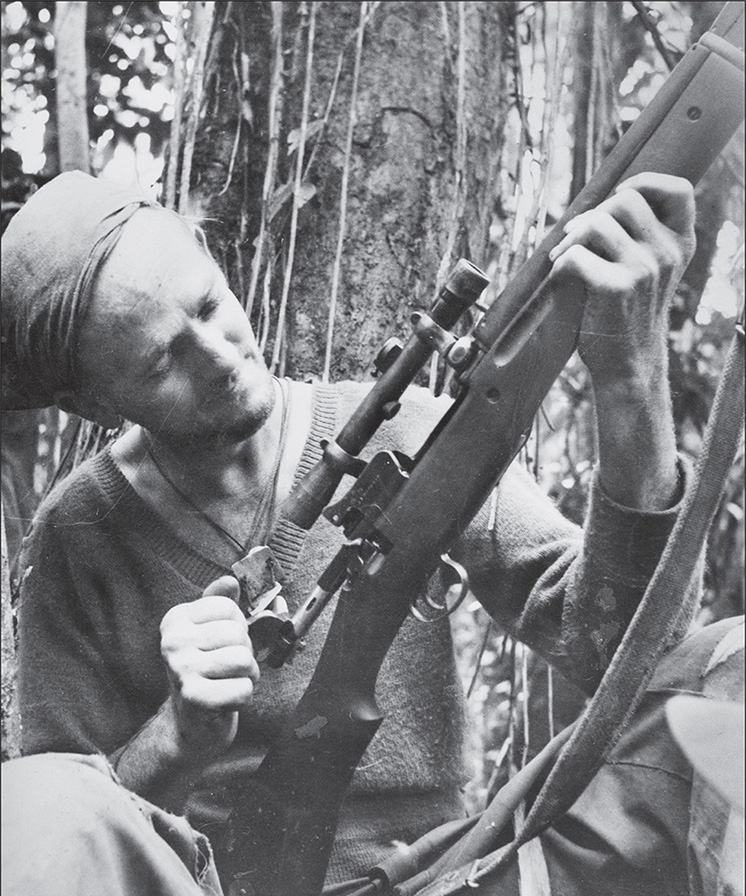

Private Harry Lake was a sniper with the 2/5th Independent Company in New Guinea. In a history of the unit he is described as ‘one of the oldest members of the 2/5th. Tough and wiry, he was a keen-eyed sniper and a former Kangaroo hunter.’ His weapon of choice was his personal cut-down, heavy barrel SMLE (AWM 013155).

With the declaration of war in 1939, the Commonwealth of Australia implemented its National Securities Act, one aspect of which was the requirement for the public to surrender a variety of weapons. In this way the Army obtained a number of SMLE ‘H’ models from the sporting shooting community. These sporting rifles are difficult to distinguish from the standard SMLE, apart from the rear aperture sight and the practice of cutting the front wood away from the barrel to reduce weight and ‘swelling’ which could interfere with the barrel’s harmonics. Lithgow continued to manufacture the heavy barrel SMLE for use by the Army’s battalion marksmen and snipers, some of the latter preferring the heavy barrel SMLE over the P14 sniper rifle.

Eventually the heavy barrel SMLE formed the basis for a new sniper rifle, the SMLE Mk. III* H T (Aust), its optics a locally produced version of the Pattern 1918 scope manufactured by the Australian Optical Company in Melbourne. As production did not commence until 1944, few ‘T’ models were available for operations before the end of the war. It was not, therefore, a key sniper system during the Second World War.

Establishments and equipment for snipers

The Provisional War Establishment and Equipment Tables for the Australian Army show how the structure of the infantry battalion changed during the Second World War to accommodate the requirement for snipers. One of these files, held by the Australian War Memorial, contains a copy of a lecture by Lieutenant Colonel J.C.W. Baillon, General Staff Officer at Headquarters 2nd Australian Division. This lecture, dated December 1939, advised that the establishment of the infantry battalions was to change ‘at once’ and that this change was to acknowledge the importance of individual marksmanship:

There is a distinct task for rifles in the hands of trained marksmen … For that reason, two men from each [infantry] section are, under the new organisation, specially trained as snipers. … Eight rifles per battalion are equipped with telescopic sights, and, in the hands of the battalion’s best shots, there [sic] weapons are capable of inflicting demoralising casualties, and so harrassing [sic] the enemy.

Lieutenant Colonel Baillon’s lecture appears to have been indicative of intent rather than definite change. While this was consistent with the practice and structure of the infantry platoon in the last few years of the First World War, the infantry battalions that were formed in late 1939 for service overseas as part of the Second AIF contained no formal establishment for snipers. Nor was ‘sniper’ or even ‘marksman’ recognised in the long list of Army specialists who attracted additional pay such as armourers, drivers/mechanics, farriers and bootmakers. The delay in creating a formal establishment for snipers was understandable considering the extensive list of priorities with which the Army had to contend on the outbreak of war and the fact that the British Army, with which the Australians were to operate, did not have establishment positions for snipers. Consequently, the employment of snipers in the Second AIF in the first two years of the war appears to have been ad hoc and at the discretion of the unit’s commanding officer. In this early period of the war the designation ‘sniper’ was rarely used, except in media reports; those performing sniper-like functions in the battalions were generally referred to as marksmen.

Men from D Company, 2/13th Battalion, at Tobruk in April 1941. While the Australian rifleman performed some incredible feats of marksmanship in the Western Desert, Greece and Crete campaigns, they had received no specialist sniper training and, apart from a few exceptions, were armed only with the standard SMLE Mk. III* rifle (AWM 007480).

Some battalion commanders with First World War experience understood the value of the battalion sniper and developed their own capability, notwithstanding the establishment tables. In a number of the battalions a scout platoon was maintained with similar responsibilities to its First World War predecessors, which included sniping. This usually meant that the battalion scout platoons ‘contained a few marksmen’, whereas in some of the other battalions the role of sniper simply fell to the unit’s best shots in each of the infantry sections. The 2/1st Battalion’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Eather, had two or three ‘marksmen’ in each of his infantry companies. Probably the reason he did not have marksmen in each of his sections was that, according to the battalion’s Routine Orders for 22 June 1940, there were only eight qualified marksmen and 74 First Class Shots in the battalion, although more were being trained at the Middle East Weapons Training School. Only a few of the battalion marksmen in the Middle East appear to have been issued with any specialist equipment such as sniper rifles and telescopes, and the battalion’s training programs make no mention of any sniper training until October 1941.

In Lieutenant Colonel ‘Black Jack’ Galleghan’s 2/30th Battalion, several of the battalion’s marksmen were issued with P14 sniper rifles in Malaya in early October 1941, just as the establishment for snipers was finally approved. Rather than combining his newly designated snipers at battalion headquarters, Galleghan allowed them to remain in their companies to help form company reconnaissance sections.

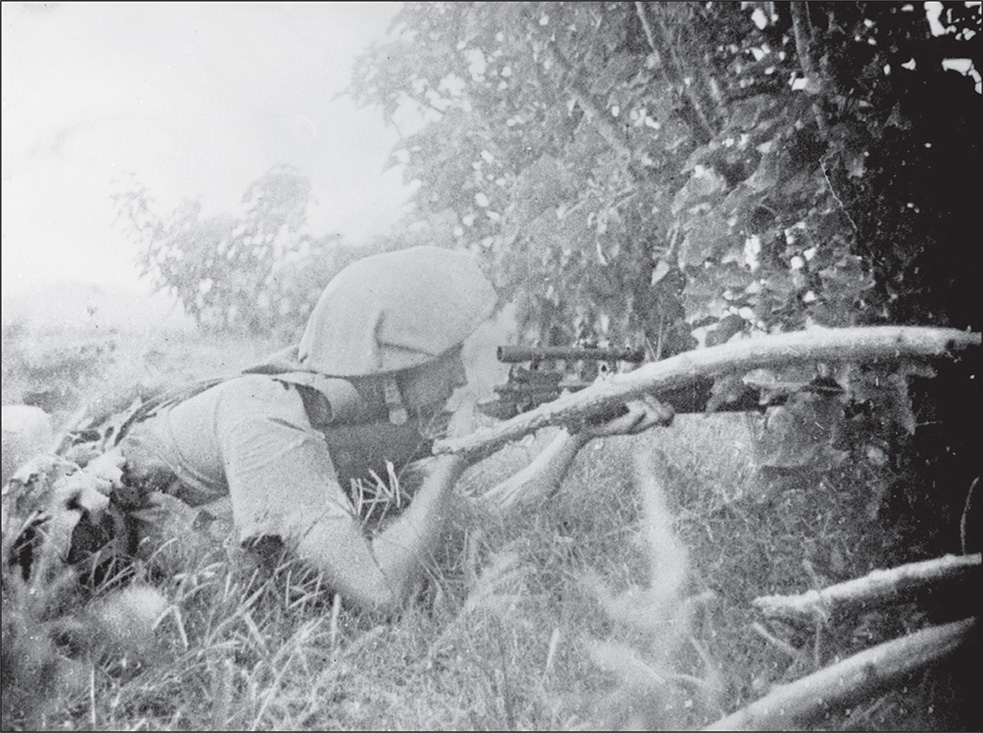

Taken in Malaya in January 1942, this is the earliest known photograph of a Second AIF battalion sniper using a specialist sniper rifle equipped with telescopic sights, in this case a Rifle No. 3 Mk. 1* W (T) or P14. Note that the sniper is paired with a man carrying a sub-machine-gun. The 8th Division was the first to use this combination which became standard later in the Pacific War (AWM 011304/18).

Apart from some of the 8th Division’s battalions, there is little evidence of the presence of sniping rifles in any of the other infantry battalions prior to 1942. A number of respected authors and historians of weapons and sniping, such as Ian Skennerton and Martin Pegler, describe the use of the P14 sniper rifle by the Australian Army in either Greece or the Western Desert and there is some anecdotal evidence to support these claims. However, apart from the 2/30th Battalion’s use of the P14, the general use of specialist sniper rifles by the Australians before 1942 cannot be substantiated by photographs or other documentary material. Prior to this date it is possible that some sniper rifles were issued to the Australian battalions in the Middle East, although there is no record of this having occurred. None of the Australian unit war diaries, equipment returns or the official histories mentions sniper rifles before 1942.

There are two possibilities to account for this. The first is that sniper rifles were simply included in the tally of standard infantry rifles. This is unlikely for the telescope-equipped rifles as many of the returns are very specific about weapon types, even discriminating between types of sub-machine guns and pistols. A rifle and scope combination was a specialist weapon and is, therefore, more likely to have been noted. In addition, no images in either the Australian War Memorial or the Army History Unit’s photographic database show telescope-equipped rifles being used by the Second AIF prior to 1942, nor do the battalion Routine Orders make mention of this type of weapon. Routine Orders were issued regularly by units covering a vast array of mundane unit administration, including the allocation of new weapons and weapons maintenance. These do not mention the arrival in theatre of any specialist rifles nor the caring for telescopic sights, which was a specific problem in the desert environment. It is possible that heavy barrel SMLEs [Mk. III* (H)] were issued to battalion marksmen and only recorded as ‘rifles .303’ in equipment returns. To the layman, these rifles are almost identical in appearance to a standard SMLE and are unlikely to stand out in any but close-up photographs.

To an untrained eye the heavy barrel rifle looks like any other SMLE. The only distinguishing features are ‘H’ stamped into the wood behind the bolt assembly and the presence of a rear aperture or sporting sight (images courtesy of Peter Bruem).

The second possibility is that units were equipped with required and available specialist equipment as they moved into a specified area of operations, particularly if they were relieving another unit, and handed it back when they departed. This was vital where equipment was scarce, as it was throughout the early period of the war. At Tobruk the 9th Division was issued a variety of essential equipment to enable it to perform its tasks, but was required to hand it all back when either the division’s role changed or it departed Tobruk. According to the Australian Official History, when the 2/13th Battalion moved from Tobruk in late 1941, ‘The battalion had handed over to the Yorks and Lancs all its equipment except what had been ordered to be carried on the man on embarkation.’ This may account for the allocation of sniper rifles to those battalions on the outer perimeter of the Tobruk defence, but only while they were located there. As the Army suffered from acute shortages of everything from buttons to Bren guns, it is likely that scarce specialist equipment, such as rare sniper rifles, would be shared.

Within a few months of the outbreak of war the British lessons learnt from opposing the German invasions of Norway in April 1940, and France and the Low Counties the following month, had begun to reach the Australian forces then training in Palestine. Some of these lessons related to the effectiveness of snipers. The British had to relearn one of the lessons from the First World War — that the correct employment of snipers and marksmen could delay a substantially larger enemy force for several hours, destroy enemy equipment and even kill enemy gun crews. It was partly for this reason that the British Army produced Military Training Pamphlet No. 44, Notes on the Training of Snipers, and opened a sniper wing at its Small Arms School in late 1940.

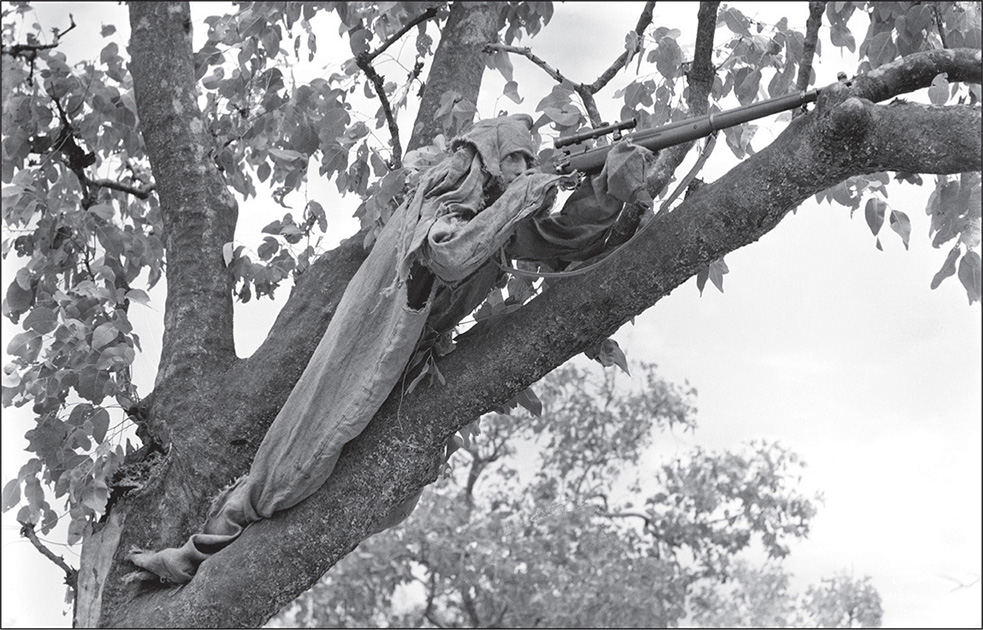

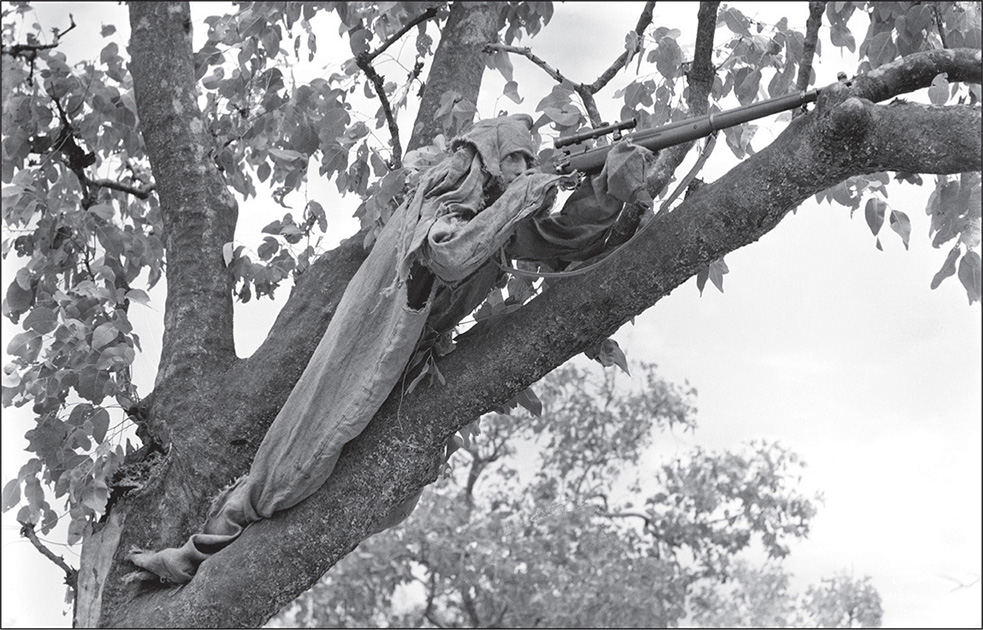

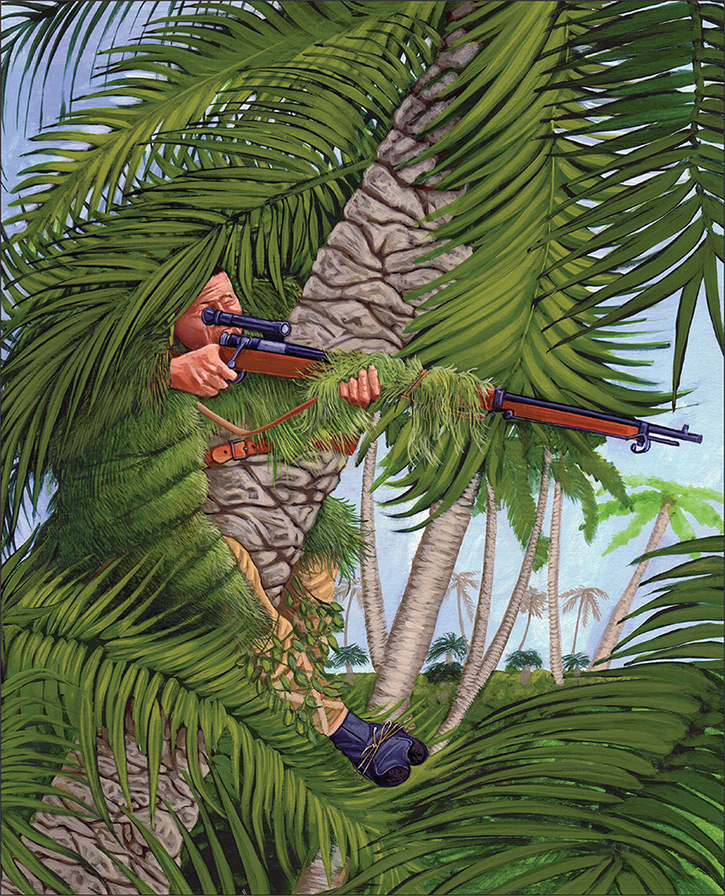

An Australian soldier attending a sniper course in Darwin in 1942. His camouflage clothing is made from a hessian bag coloured with green ink. This is most likely a posed photograph; due to difficulties in exfiltration, no experienced Australian sniper would establish his position in a tree (AWM 027768).

The Australian Army reproduced and distributed the British Army training pamphlet on sniping, but no immediate action was taken to adjust battalion establishments or implement sniper training programs. It was not until late 1941, following experience in employing marksmen against the Germans in North Africa, Greece and Crete, that the Australian infantry battalion’s establishment and equipment tables were finally amended to formally incorporate snipers. This change re-established a sniper section of eight men consisting of one sergeant, one corporal, two lance corporals and four privates under the battalion’s intelligence officer. In effect this was a similar sniper establishment to that of 1916–17, and allowed four sniper pairs to be employed at the discretion of the battalion headquarters. The battalion’s equipment tables were also amended to include eight P14 sniper rifles and six Signaller Telescopes Mk. IV**. The actual employment of snipers varied in the battalions, with some preferring to allocate sniper pairs to each company or even to infantry sections or Bren-gun carrier platoons.

This establishment was amended again in November 1942, increasing the number of snipers in each battalion from eight to 12, and allocating them to the battalion headquarters company. A further establishment change in 1944 saw the introduction of the Infantry Battalion (Tropical Scale) which included one sniper in each infantry section. This increased the total number of snipers in the battalion to 32, closer to the British Army’s establishment for snipers in a parachute battalion (32) or an air landing battalion (38). Considering that in 1944 there were around 56 infantry battalions and six commando squadrons either on or training for operations, this made the total number of snipers in the Australian Army over 2000. Understandably, there were insufficient sniper rifles for every man, although this does not seem to have created too many difficulties. Many of the snipers seem to have preferred to use a combination of rifles with aperture rather than telescopic sights, such as the heavy barrel SMLE, the British No. 4 rifle and even the American M1 Garand.

In late 1941 Australia established its first Special Forces units. Initially known as independent companies, the name was later changed to cavalry commando regiments and squadrons, and all contained an establishment for snipers equipped with a P14 rifle and scope or, on some occasions, their own private sporting rifle.

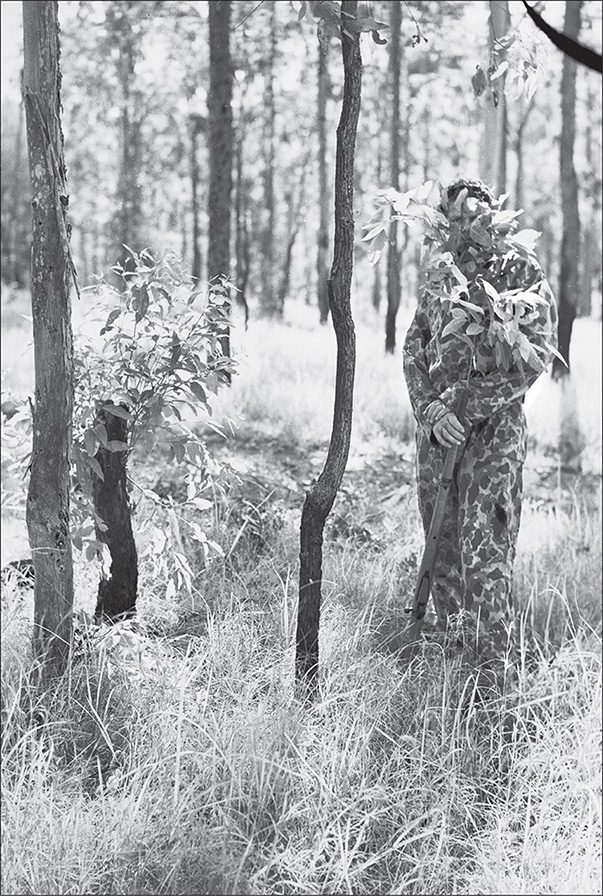

Sniper training

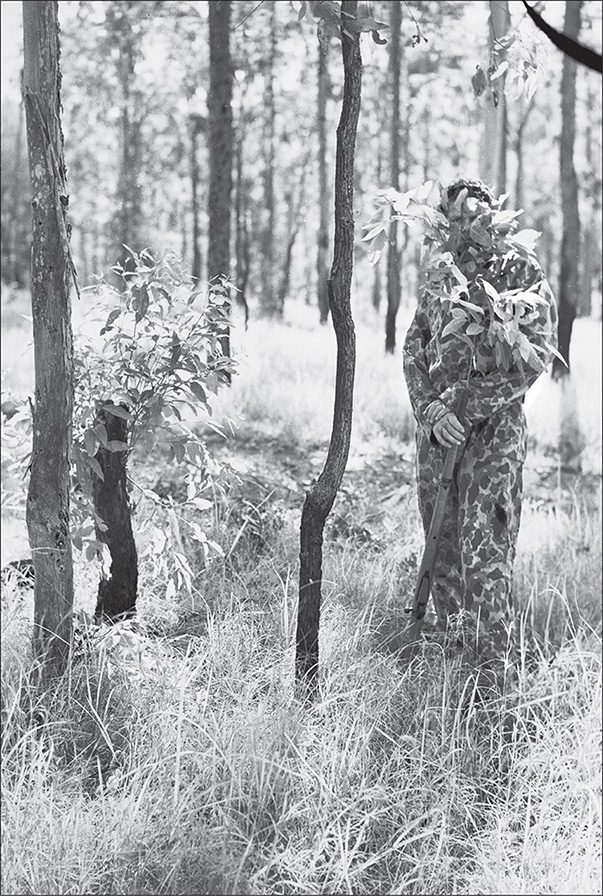

Snipers training at Headquarters I Corps in Queensland, 1944. The image on the left shows three snipers camouflaged in a simulated refuse heap. On the right is one of the snipers displaying his camouflage suit or camouflage netting. He is holding an SMLE Mk. III* H. While displays like this were common for public relations purposes, few snipers employed such camouflage nets on operations as they were considered too cumbersome and hot in the tropics and tended to restrict movement in the jungle (AWM 083465; 083467).

Notwithstanding the lecture by Lieutenant Colonel J.C.W. Baillon quoted above, and the British and Australian experience proving the value of snipers, formal sniper training was very rare in the first two years of the war. In late 1941, the Australian Army’s Small Arms School at Randwick introduced sniping into its curriculum. The school trained junior officers and non-commissioned officers as small arms instructors for units. Instruction in sniping was very basic: ‘there was only time to give an outline of what to teach and how to teach it and to lay down the general principles’. However, it included sample range practices, care and use of the sniper rifle and exercises in observation. This was considered an adequate foundation on which the battalions could build their own training.

The inclusion of even basic sniping tuition in the Small Arms Instructor’s Course was essential for the battalions. According to the war diaries of the Australian infantry battalions, only a few battalions incorporated sniper training prior to 1942, although the 2/15th Battalion conducted a sniper course as early as February 1940. Some other battalions, particularly those with men who had been snipers in the First World War, developed their own sniper training soon after the establishment of their sniper sections in September 1941. In others, however, sniper training did not occur until the arrival in the battalion of small arms instructors with some sniper knowledge.

The training syllabus for the 2/1st Battalion first incorporated sniper-specific training in September 1941. The battalion’s war diary for this month records: ‘Snipers will be finally appointed at the conclusion of the present range practices. They will be withdrawn from their Coys [companies] and given intensive coaching in marksmanship, camouflage, movement, use of ground and weapons.’ The battalion’s training program from October onwards confirms this with the inclusion of sniper training in ‘stalking, concealment, sniper rifles, sniping in open and positional warfare, and sniper OPs [observation posts]’.

The 2/30th Battalion opened a sniper school in Malaya in October 1941, running the first course for Australian battalion snipers between 7 and 17 October, only two months before the Japanese invaded the Malay peninsula. The course was comprehensive, covering concealment, map reading, field sketching, judging distance, night compass marches, reconnaissance, observation, the use of sniper hides and loopholes, telescopic sights and the sniper rifle. The course syllabus so closely followed that of the First World War’s SOS course that it is likely to have been conducted by a veteran sniper and graduate of the British school.

There is no reference to the training of actual snipers on mainland Australia until late 1941. This training was initially exclusively conducted for the independent company snipers at the Guerrilla Warfare School in Victoria. From 1942 a number of the infantry training centres, such as the Jungle Training School at Canungra in Queensland, provided courses of instruction in advanced musketry, sometimes referred to as marksmanship. These were usually an extension of the basic musketry courses designed for men who had displayed a particular talent for shooting. While initially basic, they included instruction in camouflage and concealment, the use of the sniper rifle and telescope, map reading, field sketches, observation and snap shooting. The instructors were, in the main, retired First World War men who had been snipers such as Sergeant Albert Lowerson VC, who had been a sniper in the 21st Battalion. A small sniper school was also established in both Darwin and Port Moresby in late 1942.

These courses changed substantially from late 1942 through 1943, incorporating the lessons from Australian Army operations in Timor and New Guinea and using men with more recent operational experience to replace the First World War veteran instructors. Instruction on Japanese sniper tactics was also included as were counter-sniping, camouflage and caring for the sniper rifle in jungle terrain. One man, Private Kenneth Bussell of the Volunteer Defence Corps, wrote: ‘I was lucky enough [in 1942] to be selected for a sniper school at Williamstown race course and was issued with great ceremony with an old 1908 long Lee Enfield I think 1908 stock, 1912 barrel.’

Even in 1942 sniper training was haphazard, which probably reflected the status of the art in the minds of some senior officers. Notwithstanding the British Army’s early experience in Europe against Germany, and the 9th Australian Division’s effective use of sniping at Tobruk in early 1941, some Australian officers did not believe that sniping had a role in the Pacific War. One staff officer from Headquarters Australian Military Forces in 1942, in an interview with the author, indicated that there was a ‘cadre of infantry officers that believed that the preponderance of automatic weapons in the battalion, and the shift to jungle operations against the Jap, had rendered the sniper obsolete.’ He added that ‘… even after the Fall of Singapore we arrogantly thought the Japanese soldier, and his equipment, inferior to the Australian. … the average Australian rifleman was surely more than a match for his Jap equivalent … we got that wrong, didn’t we?’

Not all men selected to be snipers were given the benefit of training. Trooper Leslie Wright of the 2/4th Commandos recalled that he received no instruction at all; once issued with his rifle he simply learned by his mistakes. In the infantry battalions the snipers received their training during battalion range practices, in lectures, on the job and at the occasional sniper course. Some of the new recruits enlisted from 1942 who had excelled in their musketry course, were given the opportunity to attend a more advanced musketry or marksman course before being posted to a battalion. Training focussed on firing over a variety of distances out to around 400 yards (366 metres), but some exceptional shots could extend this out to 600 yards (549 metres). Training and practising snipers in the art of snap shooting, which had been emphasised as a key skill of snipers in the First World War, was of enormous value in the jungles of New Guinea. In jungle fighting, engagement distances were often short, less than 50 metres, and response times had to be quick. But snipers also needed to be able to engage at much longer distances, such as across the many kunai ridges throughout New Guinea and in the mountainous, scrubby areas of East Timor. Regardless of the development of sniper training in the Australian Army throughout the Second World War, the standard never matched that available to the AIF snipers who attended the SOS Schools in France in the First World War.

Western Desert, Greece and Crete

The first Australian combat operations in the Second World War occurred during the Western Desert campaign against the Italian Army. In what was known as Operation Compass, the 6th Australian Division under Major General Iven Mackay was a key player in the attack on the fortress town of Bardia on 3 January 1941. The 6th Division’s nine infantry battalions did not formally include snipers. However, a number of the battalion commanders employed some of their best shots as marksmen within the rifle companies. One of the more common allocations, particularly by commanders with First World War experience, was the inclusion of one or two marksmen in each rifle section.

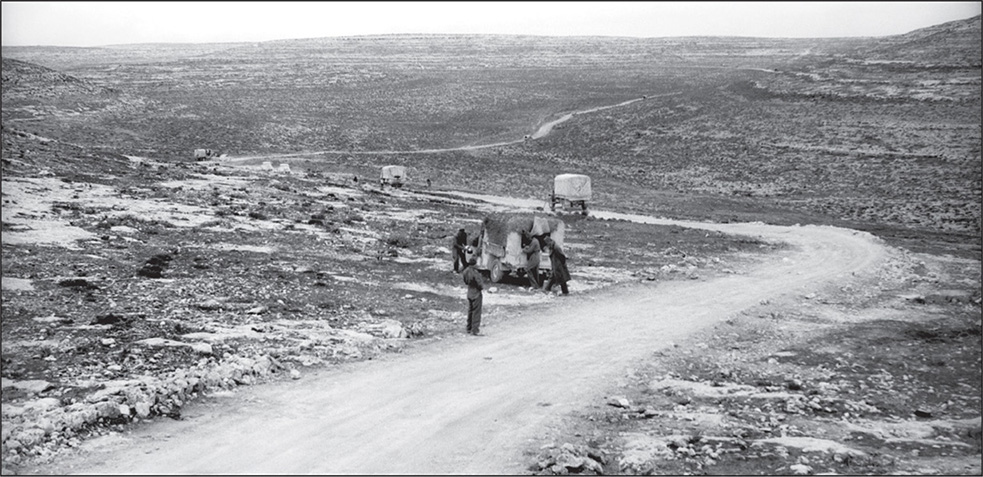

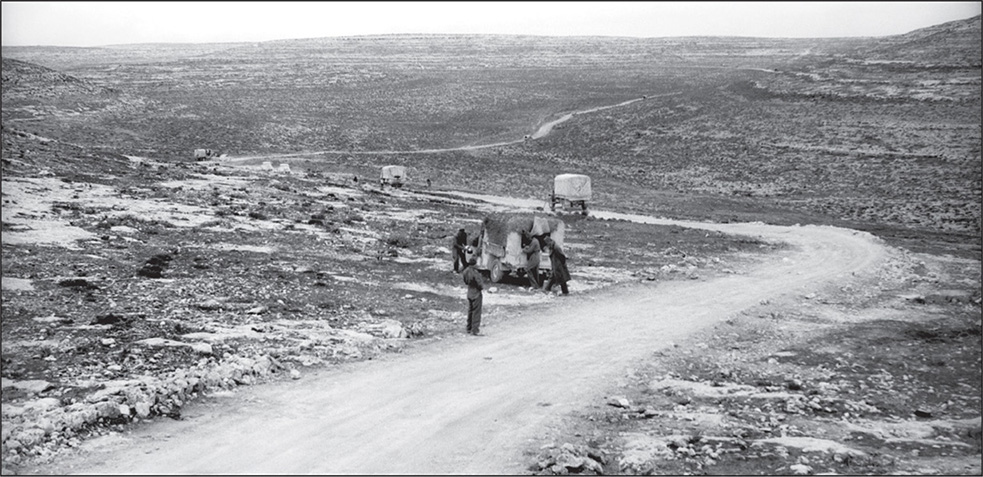

This image of the road between Derna and Giovanni Berta provides an example of the desolate countryside the Australian 6th Division fought over during the Western Desert campaign in late 1940 and early 1941. Marksmen were able to engage at the maximum distance of their weapons in this country, although they rarely fired beyond 400 metres (AWM 022552).

Any man who managed to equip himself with a telescope-equipped rifle would have soon discovered that there was little or no support for his equipment, and no spare parts. Nor were the hot and dusty conditions of the Western Desert ideal for rifle, telescope or sniper operations. In the hard, windswept and open landscape of the Western Desert, the battalion marksmen initially found it difficult to effectively employ their weapons. Cover was scarce and the firing of a rifle would often betray the firer’s location due to the small dust cloud produced by the escaping gases of the discharge. There was also the issue of heat haze obscuring the target. Even more prohibitive was a lack of understanding of how to employ snipers or marksmen in this terrain. While there was no doubt that the battalions contained some excellent shots, there were no sniper tactics, techniques or procedures available to the infantry battalion in early 1941, and the integration of marksmen into the infantry section meant they were usually fully committed to the tactical, section-level battle rather than employed at the more operational level under battalion headquarters control, as had occurred late in the First World War.

The Carcano M91 and the M38 carbine variant were the standard Italian rifles in both world wars. The M91 was introduced into service in 1892 and incorporated a Mauser bolt action modified with a Carcano bolt-sleeve safety mechanism. It was one of the first rifles to have a small 6.5 mm calibre round (small compared to the standard British 7.7 mm round of the .303 SMLE rifle). While the Italian Army equipped a number of its Carcano rifles with telescopic sights in the First World War, this does not appear to have been the practice in the Western Desert campaign. Instead, rifles that met certain accuracy standards at the factory were stamped with the Tiro a Segno Nazionale marking (two crossed rifles superimposing a bullseye target). These rifles were usually issued to the battalion’s best marksmen. The small calibre of the M91 Carcano meant that it performed poorly as a sniper rifle in comparison to the Mauser and SMLE (AHU image).

During the 6th Division’s attack on Bardia, and in its subsequent engagements at Tobruk and Derna, the Australian infantry were continually harassed by Italian snipers. While most were probably Italian infantry soldiers, many of the Italian units did contain trained marksmen, such as the elite Bersaglieri who were trained to marksman standard. The positional defence adopted by the Italians afforded little opportunity for the Italian snipers or marksmen who were largely acting as infantry manning fixed defences. Similarly, the Australian marksmen within the infantry sections were rarely employed as specialists and also primarily performed general rifleman tasks. However these men occasionally found opportunities to use their marksmanship skills. For example, at one point during the attack on Bardia, Captain Chapman, Officer Commanding B Company, 2/2nd Battalion, found himself and a group of his men in serious trouble from an Italian artillery battery just 450 metres away. Historian Craig Stockings explains how Chapman resolved his plight:

Chapman concluded that a small body of marksmen could move forward to the right flank of the battery and ‘shoot them down like rabbits’. He called for volunteers, and crept forward with three soldiers to within 150 metres of the guns. Covered from view by scattered boulders, they sniped at the gun crews and prevented the battery from firing for 20 minutes.

The Blackshirts or Milizia Voluntaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale comprised a party-oriented paramilitary organisation distinguished by its signature black uniform. The Blackshirt infantry, which was the most numerous at Bardia, contained marksmen; however, as with their two Blackshirt divisions and the remaining Italian infantry, they were poorly trained, led and equipped, and had little impact on the defence. Also present were a number of Bersaglieri companies. These were highly trained, elite light infantry, most of whom were qualified marksmen. However they were too few in number to influence the outcome of the battle (artwork by Jeff Isaacs).

Between April and August 1941, a reinforced 9th Division of around 14,000 Australians, along with attached British and Indian troops commanded by Major General Leslie Morshead, defended Tobruk against a German-Italian Army led by General Erwin Rommel. Australian casualties amounted to 559 killed, 2450 wounded and 941 taken prisoner. A number of historians have indicated that the Australians at Tobruk employed the No. 3 (T) or P14 sniper rifle. Author Ian Skennerton notes in his 1984 publication British Sniper: British & Commonwealth Sniping & Equipments that,

Good use was made of the No. 3 sniper rifle in the defence of Tobruk, where the Australians and a smaller number of British troops held out against Rommel for 8 months. … In this static type of warfare, the No. 3 (T) equipped sniper was sent out front in the salient area to become an important part of the forward defence. Special sniping instruction was made available to these men, who performed their task with distinction.

Similarly, Martin Pegler’s Out of Nowhere: A History of the Military Sniper, records that:

Though a few Australians had been able to put their skills into practical use in the desert of North Africa during the siege of Tobruk … their usefulness was limited by shortage of equipment - only a few P14 No. 3 Mk. I (T) rifles were available - and by the harsh conditions and the difficult terrain. It was not until the threat of Japanese invasion of the Antipodes loomed in 1942 that the Australian and New Zealand forces were able to begin to field snipers in some numbers.

If P14 sniper rifles were available at this time and no photographs have come to light to confirm their use by Australian infantryman, they may have come from British war stores. The exact number available and their allocation are unknown and they are likely to have been issued only to the forward infantry battalions.

The priority targets for these ‘snipers’ were enemy snipers, crew-served weapons and commanders. In the almost perfectly flat plateau, there was very little cover for the attacker, affording the battalion marksman excellent observation. For example, on the night of 13/14 April 1941, enemy armour breached the Tobruk perimeter. As dawn broke on 14 April with the attack at its height, the Germans brought forward a field gun and some anti-tank guns which they moved close to the breach in the perimeter. The Australians were able to kill or disable the crews of these guns. When another field gun and several 88 mm guns were also brought up to the breach, the Australians quickly despatched their crews as well. As the light improved, the Australian marksmen switched to targeting machine-gun teams and any officers and non-commissioned officers who could be identified.

During this action on 14 April, Private Bob Scarr, an excellent shot and marksman with the 2/15th Battalion, eliminated several anti-tank and machine-gun crews while keeping the enemy Panzers ‘closed up’. A ‘closed’ tank means that the crew keep their hatches closed, reducing their observation and often causing disorientation in the dust and haze of battle.

Enemy snipers posed a particular problem at Tobruk with several soldiers’ diaries and letters, now held at the Australian War Memorial, commenting on the accuracy of the German snipers who made movement and observation by the Australians in the forward sectors extremely hazardous in daylight hours. Australian Official Historian Barton Maughan recorded that German snipers killed one officer (Captain Jacoby) and wounded another (Major Joshua) in the 2/32nd Battalion as it assembled for an attack. The 2/15th Battalion’s war diary for 26 June 1941, records: ‘Pte Cairns killed instantly by a bullet from a sniper … Just at dusk Pte Castles … wounded through upper arm by a sniper.’ The following month the battalion’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Ogle, reported in July: ‘As an indication of accuracy in sniping, the only periscope in possession of the unit was hit as soon as it was raised above the post. In another case one man was shot through the temple when he raised his head above the parapet.’

The Afrika Korps contained a number of snipers who caused the Australians at Tobruk ‘extreme discomfort’. They generally used the standard issue Mauser K98k rifle, although a few Mauser sniper variants, including First World War Gewehr 98 equipped with a telescopic sight, were also present (artwork by Greg Blake).

Whenever identified, all posts in the area would react aggressively to enemy sniper action and, where available, use supporting artillery to destroy suspected enemy sniper positions. Each battalion also actively patrolled at night to ‘own no man’s land’. This made it more difficult for enemy snipers to establish themselves in a sniper hide during the hours of darkness. In addition, as the main Australian defensive positions were known to the Germans, some of the Australian marksmen went to great length to disguise their firing locations. Several men would endanger their own lives by moving into the exposed no man’s land at night, establishing a hide and remaining there in the heat all day without movement, only firing at dusk before returning to their lines. While an extreme risk to the marksman, according to one of the 2/17th Battalion’s marksmen, ‘it was worth it, even if we didn’t sight a target, as to fire from our trenches or posts usually attracted immediate Jerry arty or mortars.’ Some even used their own urine to damp down the dust in front of the muzzle to prevent a tell-tale dust cloud on firing: ‘water was too scarce to waste’.

However the Germans did not enjoy an unrivalled advantage. The Australian Official History, Volume III, Tobruk and El Alamein, contains an unsolicited testimonial to the Australian marksman by a German battalion commander. Major Ballerstedt commanded II Battalion, 115th Lorried Infantry Regiment which had, for a period, held the line opposite the 2/15th Battalion at Tobruk. In his captured report of 7 June 1941, he wrote that:

The Australian is unquestionably superior to the German soldier:

in the use of individual weapons, especially as snipers

in the use of ground camouflage

in his gift of observation …

in every means of taking us by surprise …

Enemy snipers have astounding results. They shoot at anything they recognise. Several N.C.Os of the battalion have been shot through the head with the first shot while making observation in the front line. Protruding sights in gun directors have been shot off, observation slits and loopholes have been fired on, and hit, as soon as they were seen to be in use…. The enemy shoots very accurately with his high angle infantry weapons. He usually uses these in conjunction with a sniper—or MG….

While the 9th Division was engaging the Germans and Italians at Tobruk, the 6th Division, along with Greek, British and New Zealand troops, faced the German invasion of Greece. Soon after the German attack in April, the Allied force conducted a fighting withdrawal towards beaches near Athens and on the Peloponnese from which they were evacuated. Many of the Australian, British and New Zealand forces were taken from Greece to reinforce the island of Crete. On Crete the Commonwealth forces faced a German airborne invasion and, after a close-run and bitter fight, the Germans eventually captured Maleme airfield, spelling the end to Allied resistance. More than 600 Australians lost their lives in the battle for Greece and Crete while some 5000 became prisoners of war.

During the Greece and Crete campaigns, one battalion sniper, Private J.J. Reid of the 2/1st Battalion, stated that he ‘rarely engaged an enemy with a sniper shot under 200 metres or over 300 metres’. According to former Army sniping instructor Lieutenant Colonel Russell Linwood who interviewed Mr Reid, this was the ideal engagement range for his standard SMLE; at these ranges he was ‘virtually guaranteed success every time, rather than risking long range engagements’. Private Reid rarely used long-range shots, and then only for harassment or ground domination purposes. In Crete he was unable to focus on his primary function of sniping as he was often tasked with other duties such as scouting and carrying one of the battalion’s Boys anti-tank guns. Nevertheless, he managed to kill a German machine-gun crew but was so tired that he gave his position away by firing too many times from the one hide and was wounded by a German sniper.

One senior Commonwealth officer on Crete, New Zealand Colonel Kippenberger, actually stalked and killed a German sniper. On arriving at a small house near Galatas that the colonel intended to use as his headquarters, he discovered that a German sniper had taken up residence. Within a short time Kippenberger had manoeuvred out of sight of the sniper, shot him and reclaimed the house. In another incident, Warrant Officer C.W. Mitchell and Private Andrew Mulgrave, both from the 2/11th Battalion, managed to capture a German rifle with telescopic sights. On 26 May they formed a sniping party and were credited with over 20 enemy casualties, some at ranges of over 900 yards (823 metres).

The German paratroopers (Fallschirmjäger) who landed on Crete included a small number of snipers in each of the battalions equipped with Mauser K98k sniper rifles. In this photograph the sniper is second in the line and carrying a low-turret K98k with a Zeiss Zielvier four-power scope (AWM 106487).

German snipers

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Germany pressed into service many of its First World War Scharfschützen Gew 98 and K98b, the latter a post-World War I variant of the Gew 98. Germany had also commenced a program to adapt its current infantry rifle, the K98k, as an effective sniper variant. Special requirements were outlined for the K98k sniper rifle which covered the selection of the rifles at the factories, the level of accuracy, fitting of the sights and even the ammunition to be used. From 1939 German snipers had access to high performance 7.92 mm ammunition in ball, armour-piercing and tracer. Sniper rifles were not only being produced at the Mauser factories but also by several other arms manufacturers, including Steyr and Sauer, with additional weapons converted to sniper rifles by enterprising local unit armourers. These rifles were supported by a variety of scopes, ranging from 1.5 to four power, and a commercially acquired six power.

The German military clearly learned from its First World War experience as German snipers were generally allocated to an infantry battalion’s headquarters, although they could also support companies for specific operations. Battalion marksmen were also common. These were well-trained infantry equipped with either a sniper rifle, if one was available, or a standard K98k Mauser, and held at platoon and company level. However, marksmen were not trained to the sniper’s high standard. Their employment simply reflected the German Army’s early operational experience in Poland and the Low Countries, where a marksman was able to support infantry squads in overcoming enemy strongpoints, opposing snipers and crew-served weapons, and eliminating observation posts.

German snipers clean their rifles after an action. The rifle shown here is a Mauser K98k with a high-turret Ajack four-power scope (AHU image).

The German World War II sniper rifle Scharfschützen K98k

The German Model K98k sniper rifle (Scharfschützen K98k). Its scope is a Zeiss Zielsech, six power with a 22 mm wide band Sauer & Sohn long side-rail mount (image courtesy of Dave Roberts).

With the benefit of their experience in the First World War and the advanced state of the German optical industry, Germany had the edge in producing high quality sniper rifles during the Second World War. While a number of the older Gew 98 sniper rifles remained in service in 1939, they were eventually replaced as the Wehrmacht adapted its new standard infantry rifle, the 7.92 mm K (Karabiner) 98k, for the sniper role, the main difference an improved scope on a shorter barrelled rifle.

Initially, various models and adaptations were trialled and fielded, including short and long side-rails; turret and claw mounts; and numerous telescopic sight combinations — even captured Russian scopes. Eventually, however, selected K98k rifles that had proven exceptionally accurate during factory tests were fitted as sniper rifles. These rifles proved accurate out to 1000 metres when used by a skilled sniper. German industry was able to provide the Wehrmacht with a range of options for its sniper scopes. German optics, as used in Wehrmacht armoured vehicles, were generally superior to those used by the Allies and included 1.5 and four-power Zeiss scopes, and commercial telescopes such as the six-power Hensoldt sight.

Later in the war the Wehrmacht also fitted its sniper rifles with silencers (Schalldampfer) copied from a Russian design then being used against German forces on the Eastern Front. German semi-automatic rifles such as the G (Selbstladegewehr) 41 and G43 were also equipped with scopes for sniping purposes, with mixed success. These rifles took advantage of Finnish and Russian experience in semi-automatic sniper rifle development. The G43, with a ten-round detachable box magazine and a Zielfernrohr 43 (ZF 43) four-power magnification, helped address the slower rate of fire of the bolt-action rifles.

The German snipers facing the Australian troops in Greece, Crete and North Africa in the early years of the war were equipped with either the K98k sniper rifle, with a short side-rail/turret-mount system and a four-power scope, or the World War I Scharfschützen Gew 98 with scope. The K98k rifle itself was robust, accurate and reliable, used extensively throughout the war and exported to or produced under license by various German allies.

It is unclear whether the Afrika Korps employed marksmen or snipers although the German force at Tobruk certainly possessed a number of sniper rifles. During the Western Desert campaign it took the German Army some time to adjust to the highly mobile nature of the warfare and develop its sniper techniques, tactics and procedures. However, as the campaign bogged down into static warfare during the siege of Tobruk in 1941, the Germans were able to fall back on First World War sniper practices. This included moving out into no man’s land under cover of darkness to locate and attack high priority targets such as mortar and machine-gun crews, artillery observers, officers and enemy snipers. Unlike in the First World War, German snipers usually operated in pairs and there were examples of snipers engaging targets at long range to harass and force their enemy to ground; some of these engagements were out to 1100 metres.

The commando sniper

When Japan entered the Second World War as an Axis Power in December 1941, the majority of Australia’s military forces were deployed overseas. After the fall of Singapore and the ignominious surrender of the 8th Australian Division on 15 February 1942, all that remained to protect the Australian mainland were several partially trained and equipped divisions, an under-strength Royal Australian Air Force with largely obsolete aircraft, and a Royal Australian Navy with less than half a dozen battleworthy warships in the Asia–Pacific region.

In 1942 the Australian government recalled I Australian Corps from the Middle East, expanded the Militia and appealed to the United States for assistance in defending Australia from Japanese invasion. All these actions would take time to realise: the militia required substantial manpower, equipment and training; the divisions returning from the Middle East would need to be retrained and prepared for warfare in a vastly different environment; the United States would need time to establish its forces in Australia before being able to launch an offensive; Australian industry and manpower had to be placed on a war footing and the population prepared for attacks on Australia’s territories and even the mainland; and the Australian government and senior military officers needed to work out how to run a war at both the strategic and operational levels.

The situation in early 1942 was indeed dire and there were few viable military options open to the Australian government. Military units were initially deployed piecemeal across several islands to the north in the form of a screen and in the optimistic hope that they could defend key strategic installations such as airfields and report on Japanese military movements. This deployment included reinforced battalion groups such as Lark Force at Rabaul, Sparrow Force in Timor and Gull Force on Ambon. Lark and Gull Forces were quickly defeated by a much larger Japanese force. But in Timor the 2/2nd Independent Company, and later the 2/4th Independent Company, successfully waged a guerrilla war against the Japanese until the Australians were forced to withdraw in early 1943.

The Australian commandos in World War II emphasised firepower and, consequently, held a larger number of sub-machine guns than a normal infantry company. The two main types of sub-machine gun employed were the Thomson Gun (top) and the Owen Machine Carbine. The Thomson or ‘Tommy gun’ was manufactured in the United States and fired a .45 inch round. The Owen was designed and manufactured in Australia with a 9 mm version introduced into service from late 1942. The Owen was more robust, reliable and cost effective compared to the Thomson and remained the main Australian Army sub-machine gun until replaced by the F1 during the Vietnam War (AHU images).

The independent companies were Australia’s first Special Forces and were raised after Australia received British advice that possessing a special force of men trained in ‘raids, demolitions, sabotage, subversion and organising civil resistance’ may prove beneficial. The first unit, the 1st Independent Company, was raised in early 1941 at a special training camp established for this purpose at Wilson’s Promontory in Victoria. Officially referred to euphemistically as the 7th Infantry Training Centre, it was better known as the Guerrilla Warfare School. Four independent companies were raised before war erupted with Japan and, while there remained some confusion as to the precise role of the commandos, they were quickly deployed. The 8th Australian Division also called for volunteers to raise an independent company in Malaya after the Japanese invasion on 8 December.

The size, role and equipment of the independent companies varied according to their role. Generally they had a strength of around 273 all ranks and consisted of a headquarters, commanded by a major, and three platoons each with a captain in charge. Each platoon consisted of three sections of 16 men commanded by a lieutenant; the section could be further broken down into two patrols. While there was a standard allocation of weapons to a section, a typical composition was four sub-machine guns (Thomson initially then the Owen gun), one Bren gun, one SMLE Mk. III (usually with an EY grenade launcher attachment), one No. 4 Mk. I (the British Army version of the SMLE), one P14 sniper rifle and two .38 pistols (carried as secondary weapons by the sniper and Bren gunner).

The company usually had integrated mortar, medical, engineering, transport, quartermaster and signals detachments that could sub-divide to support each of the platoons. The independent companies emphasised firepower and, consequently, held a larger number of sub-machine guns and Bren guns than a normal infantry company. Each section also contained two snipers armed with either a heavy barrel SMLE or a P14 equipped with a telescopic sight. The individual sniper appears to have had some discretion as to the type of rifle he used, with some actually deploying with their own sporting rifle. Even some of the officers carried unusual weapons. In the 2/2nd Independent Company the engineer officer, Lieutenant Turton, also carried a sniper rifle. In one instance Turton shot a surprised Japanese soldier from the hip at a distance of just a few metres, with the company’s historian noting that ‘… this is hardly the use laid down in the manuals for a sniper rifle with telescopic sights’.

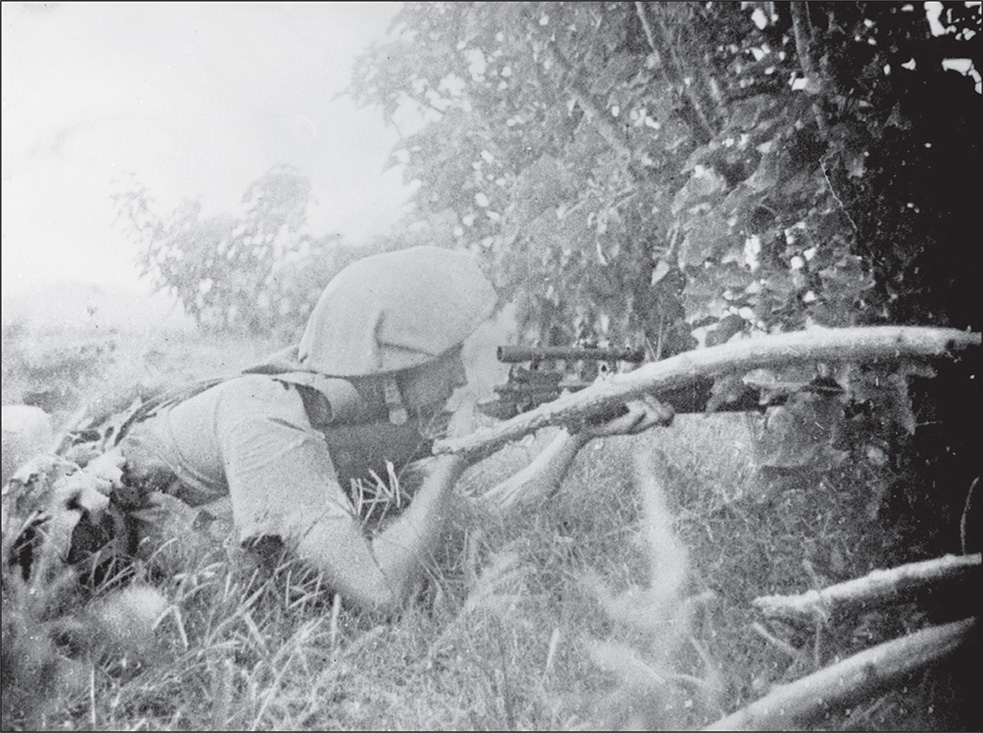

Well-known film and documentary maker Damien Parer visited the commandos on Timor in 1942. This photograph taken by him shows a 2/2nd Independent Company sniper armed with a P14 rifle equipped with a P18 scope. While in Timor, Parer also filmed a documentary titled Men of Timor which contained several images of Australian Army snipers in action (AWM 013827).

Some of the earliest documentary evidence available today of the use of a telescope-equipped sniper rifle in the Australian Army during the Second World War comes from Timor in early 1942. Both the 2/2nd and, later, the 2/4th Independent Companies used their P14 sniper rifles to good effect in an unrelenting guerrilla war against a much larger and experienced Japanese force. Living off the land in harsh conditions, the commandos killed an estimated 1500 enemy for the loss of 40 men. The 2/2nd Independent Company’s history records that the ‘first Japanese to be killed was a richly dressed gentleman who was foolish enough to ride a horse whilst the remainder walked, and he was quickly followed by two other officers who made themselves obvious.’ It goes on to indicate that these Japanese officers were killed by one of the company’s snipers, an ex-Kangaroo shooter, probably Private Doug Weatley, who had 47 confirmed kills while serving in Timor.

While the actions of the independent companies on Timor had limited long-term effect, they forced the Imperial Japanese Army to divert reinforcements that could have been effectively employed in New Guinea. Timor was also important from another perspective. The independent companies proved that sniping in a jungle environment was not only practicable but also a valuable force multiplier. As a commando force, the ability of the sniper to hit a high-value enemy target unseen and from a distance, was invaluable and had a marked detrimental effect on Japanese morale.

The independent company snipers gained an early reputation for their accuracy, tracking and detection skills. Many were professional hunters in civilian life, or award-winning sporting shooters. Author Martin Pegler quotes a British captain who witnessed a 2/2nd Independent Company sniper in action in Timor:

Shore commented that the kangaroo hunters were remarkably good shots, used to the .303 rifle and seldom missing a target. In fact, in Shore’s opinion, the Australians provided the most remarkable snipers of the whole war. In proof he quoted the instance of one kangaroo hunter on Timor who would not bother to put the scope on his rifle for shots under 300 yards and who was credited with 47 kills, and another who shot 12 advancing Japanese with 12 shots in fifteen minutes.

During operations at Kaiapit, New Guinea, in September 1943, the 2/6th Independent Company had a strength of 191 men including eight snipers. According to the company’s officer commanding, Major Gordon King, the unit’s snipers contributed significantly to the ‘approximately 300 enemy killed over the two-days of battle’. One of the snipers, Private Wally Roach, was credited with several kills at 300–400 metres range with a scoped P14 rifle during this battle.

In October of the same year, the 2/2nd Commando Squadron, the unit name having been changed from independent company earlier that month, was operating in the Ramu Valley, New Guinea. On 25 October a patrol from the 2/2nd, under the command of Lieutenant Doig, was reconnoitring new territory when they recognised signs of recent Japanese activity in a small village. Part of the patrol went forward to investigate when, according to the Official History, suddenly ‘everything including the kitchen sink flew through the air’ and Doig was ‘forced to withdraw rapidly (and how)’. Part of the section providing fire support contained one of the unit’s snipers, Trooper Craig, who ‘killed about six Japanese with his sniper’s rifle’.

Not all the fighting in the Pacific occurred in dense jungle. Areas of Timor and New Guinea, for example, had large grassy fields or lightly wooded areas that provided excellent sniping positions. This image is of the plains at Kaiapit, New Guinea, where Private Wally Roach, a sniper with the 2/6th Independent Company, successfully engaged targets at 300–400 metres range with his scoped P14 (AWM 096199).

During operations at Mubo, New Guinea, in January 1943, an enemy soldier jumped out of a banana patch, thumping his chest and calling to the Australians. Lieutenant Pat Dunshea, who was then a section commander with the 2/7th Independent Company, assumed that the Japanese was attempting to draw the Australians’ fire so he could identify where on Vickers Ridge the Australians were located. ‘At over 600 yards [550 metres] he was expecting us to miss.’ One of the 2/7th’s sniper teams used an artillery range finder to estimate the distance to the target. This data was then transferred to the sniper’s telescopic sight and the Japanese soldier was killed.

Another 2/7th Independent Company sniper, Private Don Latimer, later provided a detailed account of his experiences as a commando sniper in New Guinea. Latimer joined the 2/7th Independent Company in February 1943 and was trained at the Guerrilla Warfare School in Wilson’s Promontory, Victoria, and at Canungra. While he did not receive any specialised sniper training, soon after his arrival in New Guinea his ‘boss came in and asked if there was anyone who had been a rifle club shooter before the war. My mates dobbed me in and I was told to report to the Sergeant armourer [as] he had just taken delivery of 3 sniper rifles and was looking for someone to use them.’ The rifle was a P14 with a Pattern 1918 scope:

I liked it very much. It was a good, accurate rifle with a Mauser-type [action] … and a smooth two-stage trigger, but it seemed long and heavy after the SMLE. It was a bloody nuisance in the jungle. … Once we were in action I usually left the rifle with the ‘Q’ at platoon base camp as in our patrol actions we needed Owens more for fire power in our contacts.

Nevertheless, there were occasions when his sniper rifle was required:

Sometimes the patrol leader would tell me to bring the sniper rifle. I could pick off a few Japs at long ranges, 600 – 800 yds [550–732 metres], across a valley … I would not stay any more than half an hour popping away and then get out while I was still lucky. I was also used a bit when we were watching the Japs in a village … they would turn me loose. … After a dozen shots you would have them [the enemy] running around like ants. If they had a clue as to your whereabouts they usually started the mortars going … You had no mates when you were sniping because you drew the crabs so quick.

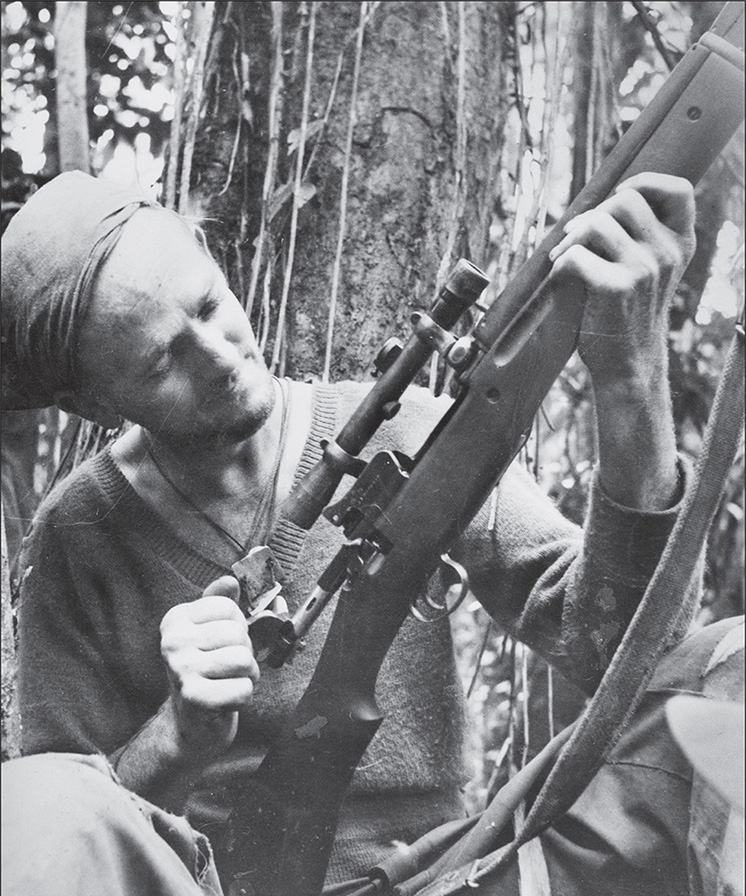

Private Clarry Elliott clears his P14 sniper rifle at Goodview Junction, New Guinea, in September 1943 (AWM 015729).

Latimer also used the sniper rifle from a hide to cover tracks known to be used by the enemy, or that led into an Australian unit’s position or to a river crossing. His most effective action was in late 1943 in the Finisterre Ranges in New Guinea near Kesawai:

The Japs had a camp in a native village and we decided to stir them a bit. The Intelligence section had a portable range finder and the night before an escort took me there and I selected a possie overlooking the village. The range on the range-finder was 800 yards [732 metres] and I got set up and they left me to it. I stayed most of the next day shooting up the village and anything that moved. I know I got 6 definite hits which was my best ever for a day, but I really stirred the Japs. They used a lot of mortar ammunition trying to find me.

The independent companies had a change of name in late 1943, becoming the cavalry (commando) squadrons and finally simply commando squadrons. They continued to retain a special forces structure and ethos while maintaining the sniper as an integral part of the unit.

Pacific theatre

The Japanese invasion of Malaya on 8 December 1941 was opposed by a combined British, Australian, Indian and Malayan force under the command of newly promoted Lieutenant General Arthur Ernest Percival, General Officer Commanding (Malaya). It concluded with the ignominious surrender of Singapore and all British forces on 15 February 1942, including 15,000 men from the Australian 8th Division. As Singapore was a powerful symbol of British dominance in South-East Asia and an integral component of Australia’s defence policy, its fall was not only a significant military reversal for the Commonwealth, but precipitated a national crisis in Australia.

Lieutenant General Lionel Bond inspects Australian 8th Division troops on parade in Kuala Lumpur (IWM KF267).

While the battles to defend Malaya and Singapore were remarkably short, the 8th Division was able to learn from its experience in fighting the Japanese and scored several remarkable successes, most notably at Gemas, Bakri, Jemaluang and the Muar River. The General Officer Commanding the 8th Division, Major General Gordon Bennett, escaped Singapore under controversial circumstances, citing the importance of communicating to Australian military authorities what he had learnt about fighting the Japanese. One of the lessons from the Malaya campaign was the Japanese employment of snipers. Throughout the fighting in Malaya and Singapore, Japanese snipers were very effective in hampering the movement of the Indian and Australian infantry. The Australian 2/30th Battalion’s history notes that movement ‘was made more difficult and hazardous by the activities of snipers, who seemed to be in every house and tree’.

While each of the Australian battalions included a section of snipers equipped with some P14 sniper rifles, these sections had only recently been formed and there had been insufficient time for training. In addition, most Australian officers and senior non-commissioned officers had little understanding of how to employ snipers in a jungle setting as no sniper tactics, techniques or procedures had been developed. Some of the battalions attempted to employ their snipers against the Japanese, notably the 2/30th Battalion in its ambush at Gemencheh Bridge on 24 January and the 2/18th Battalion in its defensive action at Nithsdale Estate on 26 January. However, lack of experience meant that the snipers played only a very minor role in these engagements. By the time the 8th Division had fought its way down the Malay peninsula and crossed the causeway into Singapore, its battalions had suffered heavy losses of both personnel and equipment. The 2/19th Battalion, for example, received 650 reinforcements in Singapore and the 2/29th Battalion required 500 men. Consequently, none of the battalions re-formed its sniper teams after arriving in Singapore and sniping thus played little or no role in the remainder of the campaign.

However one major sniping lesson emerged from the 8th Division’s training in the Malayan jungle and its contact with the Japanese. Unlike the Australian Army’s Western Desert experience, snipers armed with a scoped rifle were at a major disadvantage in the jungle environment. With engagement distances extremely short — often less than 50 metres — the sniper had to react almost instinctively, which was difficult with the narrow field of vision on the Pattern 18 scope. To address this, the sniper’s spotter usually carried a Thomson sub-machine gun (see image of 2/30th Battalion sniper in Malaya). On counter-sniping tasks the group could also include a man armed with a Bren gun.

After the fall of Singapore, and as part of their strategy to isolate Australia from the United States, Japanese forces landed at Lae and Salamaua on the mainland of New Guinea in March 1942. Their plan to capture New Guinea’s capital, Port Moresby, in an amphibious assault was thwarted by the defeat of the Imperial Japanese Navy in the Battle of the Coral Sea, and was later postponed indefinitely after the Battle of Midway. Consequently, their plan was amended to the capture of the Buna–Gona area on the north coast of New Guinea, which they achieved in July 1942, followed by an overland advance on Port Moresby via the Kokoda Track. The beginning of the Kokoda Track campaign began on 22 July when the Japanese South Seas Force first clashed with a much weaker Australian militia brigade. While the Australian Army rushed experienced troops recently returned from the Middle East and other militia formations to New Guinea, it took time to slow the Japanese advance, and the Allies would not go on the offensive until mid-1943. As the last Japanese position on mainland New Guinea did not fall until May 1945, it was to be a long, hard campaign.

At the beginning of the Pacific War the Australian Army was unsure of how best to employ snipers in jungle terrain, although there does appear to have been some acknowledgement that their employment was essential in any guerrilla force. For this reason snipers were included in each of the independent companies raised in late 1941 and 1942. Based on British advice and the experience of the Australian 8th Division in Malaya, a number of the battalions also raised guerrilla reconnaissance (GR) platoons in early 1942 which included snipers. On 15 April 1942, for example, the 2/1st Battalion created a battalion GR platoon while in Colombo (in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka). Training was provided at a GR school established for this purpose which trained both Australian and British GR personnel.

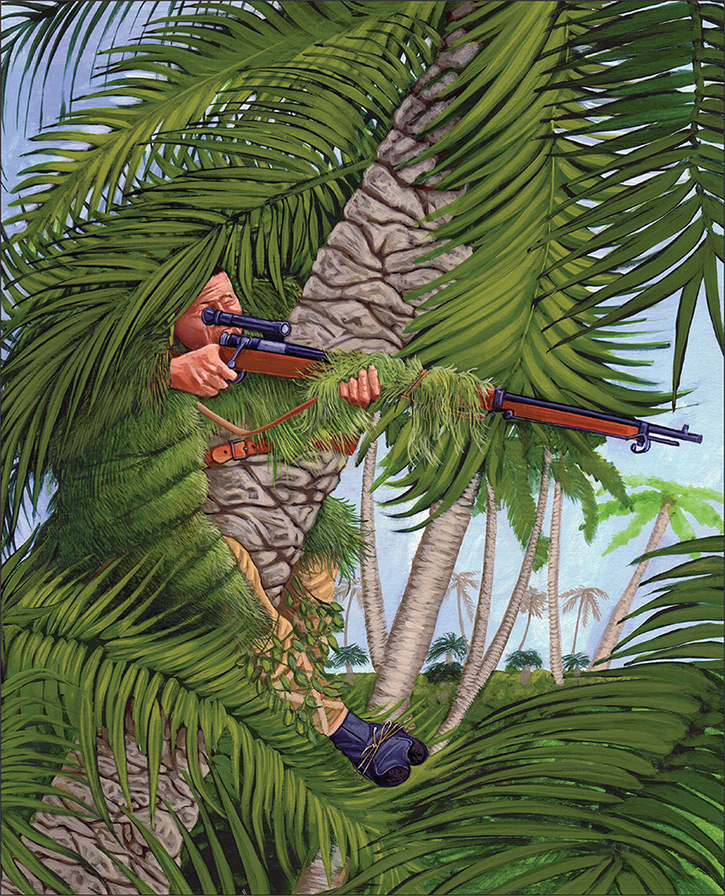

A Japanese treetop sniper lies dead at the base of his tree in New Guinea in late 1942. At the top of the sniper’s outstretched right hand is his broken rifle. An Australian soldier sighted the sniper and shot him using several bursts from his Bren gun. The gunfire weakened the upper section of the tree so much that the weight of the sniper caused the treetop to break and he was killed when he hit the ground 20 metres below (AWM 013937).

The GR platoon, usually only a section in strength, was structured, trained and operated much like a patrol section from an independent company. It was commanded by a lieutenant and trained in demolition, reconnaissance, map reading, field sketches and sniping. The GR operational concept was very flexible, as few battalion commanders really knew how to employ them. They could operate independently or amalgamated with other GR platoons under divisional control and were structured to operate behind the enemy’s main force and conduct ‘harassing operations’. Eventually, after some experience in jungle warfare, the GR platoons were primarily tasked with reconnoitring enemy positions; finding outflanking routes; locating enemy mortar, machine-gun and artillery positions; and interfering with enemy supply lines.

During the Battle of Eora Creek in late 1942, the 2/1st Battalion’s GR platoon, under Lieutenant ‘Mac’ Nathan, was employed to move behind enemy defensive positions in an attempt to ‘interfere with his supplies’ and locate Japanese mortar positions. The 2/1st Battalion’s history describes the GR platoon as ‘a team of happy bandits trained in all the nasty little facets of commando skulduggery’. In October that year, after a series of engagements, the battalion was so under strength that the GR platoon was disbanded and the men transferred to the infantry companies. By November 1942 all GR platoons had been formally disbanded and replaced with a section of 12 snipers who were either allocated to the battalion’s headquarters company or placed under command of the intelligence officer. In some battalions the commanding officers continued to employ their snipers within each of the infantry companies. In addition, most of the infantry platoons maintained a marksman capability. In Sergeant Bede Tongs’ 30th Battalion, a sniper section was formed under the intelligence officer late in 1942 during operations on the Kokoda Track. This section was also issued with six aging Canadian Ross sniper rifles.

Regardless of the variety of ways in which the battalion snipers were allocated and the rifles they were issued, one of their key roles early in the Pacific campaign was counter-sniping. Initially the battalions used their snipers as a type of forward scout to reconnoitre and destroy enemy sniper positions. In New Guinea, combat distances were often less than 50 metres. Snipers had to be instinctive snap shooters. Telescopic sights were more of a hindrance than a help shooting in this environment; however they proved of value in observing and scanning potential enemy sniper positions. Various methods of dealing with enemy snipers were trialled, but it was not until after the Battle of Buna that the concept of a specialist counter-sniping team was developed.

The ‘Report on Operations in the Buna Area’ by the 18th Australian Brigade in January 1943 highlighted the fact that, due to the ‘extensive use of snipers by the enemy’, it was ‘essential in any plan of action that, as an integrated portion of that plan, a specific course of action should be laid down for dealing with snipers.’ The report went on to describe the various ‘anti-sniping parties’ the 18th Brigade employed and their use of mortars, artillery, medium machine-guns and smoke to deal with the sniper menace. From early 1942 counter-sniping became more coordinated and integrated into the battalion’s or brigade’s plan for both the defence and attack. Counter-sniping teams also evolved to include observers, snipers, men armed with automatic weapons such as sub-machine guns and Bren guns, and decoys. The decoy’s dangerous job was to attract the fire of the enemy sniper so that the remainder of the team could target him. A variety of ruses were employed from grass-stuffed dummies to men running between cover. At least one battalion recorded ‘around 22 enemy snipers dispatched’ in one day using these sniper-hunting teams.

Japanese snipers frequently used treetops from which to identify and fire on targets. They often wore spiked over-boots to assist climbing and donned local camouflage. Many of these snipers were, in effect, conducting suicide missions as they were rarely able to descend or even move without being seen by their enemy and targeted. If captured they were often shot. Few snipers in either the European or Pacific theatre of operations became prisoners of war (artwork by Greg Blake).

The Japanese did not exclusively use treetop snipers. In some areas, particularly where the jungle was sparse, snipers would operate from a ‘spider hole’. This was a well-concealed trench or pit that afforded the sniper excellent observation, was often mutually supported by riflemen, machine-guns and mortars, but extraordinarily difficult to detect. It was not uncommon for clear lanes of fire to have been established in front of the sniper’s position. To combat these snipers the counter-sniping patrols would include a forward observer to call in artillery or mortar fire ‘in an attempt to devastate the area’.

According to the Australian War Memorial’s records, the independent companies were also employed on ‘sniper-hunting patrols’. The 2/6th Independent Company was engaged in such a patrol during the Buna operation on 2 December 1942 when one of its patrol leaders, Captain Rossall Stuart Belmer, was killed by one of the snipers the men were hunting.

Japanese snipers were a major cause for concern to the Australian troops. Private ‘Mick’ Button of the 53rd Battalion, interviewed many years later, observed that new recruits and ‘blokes without training, well, the snipers got onto them straightaway … A bloody sniper got [one of my mates], it didn’t kill him … and he couldn’t take it. A lot of them couldn’t take it.’ During a river crossing in New Guinea in August 1942, the battalion headquarters was halfway across when ‘the snipers got onto them … They got our CO [Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Ward] and they got the bloody adjutant too.’

Sergeant Trevor King, 55th Battalion, provides some indication of the mistakes by new arrivals that made them prey for the Japanese sniper:

If you had an idea that there was a sniper high up in a tree, say to your left, and you’re looking up for him, that’s the worst thing you could do, because as you raise your white face it shows and it’s picked out in a flash and fired on. So you made sure that you looked at him through the corner of your eye or underneath your hat, or steel helmet …

Methods of dealing with enemy snipers typically involved ‘spraying’ the treetops with automatic fire or with whatever weapons were available, including shotguns and the Boys anti-tank rifle. Russell Gilbert, in his book Stalk and Kill, describes how one Australian soldier and his mate used a .55-inch Boys to take down a sniper:

With the barrel resting on my shoulder, the butt against his own, Harry took a long aim, quite undeterred by the bursts of bullets from all sides … Then Harry fired and I was crushed to the ground and Harry was flung against a tree and the sniper toppled gracelessly out from behind his tree.

By late in the war units were using creeping Vickers medium machine-gun fire from the base of the tree up to the top of the branches. Lieutenant Shelley, then a platoon commander in the 2/11th Battalion during its attack at Wewak in May 1945, indicated that his main problem was ‘from tree snipers, particularly one located in a tall rain forest tree’. Shelley considered the Japanese snipers poor shots, but they nonetheless had a major impact on morale and could hold up an attack. In this instance Vickers machine-guns were used to strip the trees of their foliage and their ‘oriental occupants’.

December 1944: machine-gunners of the 25th Battalion spray the treetops at Bougainville in an attempt to kill a Japanese sniper who is holding up the battalion’s advance (AWM 078021).

The Australians would also call in air support to clear snipers where aircraft were available and it was practicable to do so. Incidents of Beaufighter aircraft strafing at treetop level to clear snipers from trees were not uncommon later in the war. Armour was also used against snipers. At Buna and Sanananda the Stuart light tanks of the 2/6th Australian Armoured Regiment would knock down treetop snipers by butting the tree trunks. At Finschhafen and Sattelberg the 1st Australian Army Tank Battalion, later to become the 1st Armoured Regiment, used its Matildas to assist the infantry by driving up to sniper positions and destroying them at point blank range with high explosive rounds. There were also examples of American 37 mm anti-tank guns firing grapeshot or canister rounds to shred the tops of the trees and any snipers who might be in them.

Australian gunners also used their 25-pound guns in a direct fire role to counter snipers. According to the Official History, Sergeant Carson, a gun commander with the 2/5th Field Regiment at Buna in December 1942, would select an enemy soldier to be targeted:

Orders were quickly passed to the gun; all eyes were on the Jap. When the 25-pounder fired, the Jap appeared to sense that that round was meant for him. He jumped on to the parapet with the idea of making a dash. Foolish move! The onlookers assert that the shell hit him in the pit of the stomach. At all events he disappeared in instant disintegration.

The desire for automatic weapons in the jungle saw the Australians experiment with a variety of rifles. One unusual rifle used by Australian snipers in the Pacific was the US-manufactured Johnson M1941 rifle. Originally destined for the Dutch East Indies, but provided to the US Marine Corps at the outbreak of war with Japan, a number of these rifles fell into the hands of Australian marksmen and snipers in New Guinea after the Marines were re-equipped with the M1 Garand rifle. The Johnson was a unique semi-automatic weapon with a ten-round rotary magazine. It used the .30-06 Springfield ammunition and, according to some, was less accurate and rugged than either the Enfield P14 or SMLE. It is likely that the Australian snipers were keen to try something different, and a semi-automatic rifle was considered ‘high-tech’ at that time. A few of these rifles were fitted with a Pattern 1918 scope for use as sniper rifles. They are a rare collector’s item today.

The M1941 Johnson rifle, shown here with a Pattern 1918 scope as used by an Australian sniper, was manufactured in the United States for the Dutch East Indies. Japan’s entry into the war prevented their delivery and, due to the shortage of M1 Garand rifles early in the war, the US Marine Corps used these rifles alongside the bolt-action Springfield M1903. As the Marines replaced the Johnson with the M1, a number of the Johnson M1941 rifles ended up in the hands of the Australians, including Australian snipers and marksmen. Initially a novelty, ammunition supply issues (the Johnson used the Springfield 30-06 round), poor accuracy and a paucity of spares soon saw them disappear from the armoury of the Australian Army (AHU image).

Consistent with the Australians’ desire to try new equipment, in 1942 a number of diggers managed to procure American M1 Garand rifles. One sniper with the Australian 2/6th Independent Company during the Battle of Buna in New Guinea, commented that:

Our unit was only recently formed … firepower was considered very important to us. I had been issued with a pretty good Enfield [ P14] with a scope … but we soon figured out that the best way to get the buggers in the trees [the Japanese snipers] was to saturate the area with whatever we had. You couldn’t always see them, you see. You just knew approximately where they were. So, with the Garand I could get more rounds into the target area than with the Enfield … It wasn’t as accurate as the Enfield … but the Yanks seemed to have a better supply system than us so I could get ammo for it OK.