Sniping comes of age: Somalia and East Timor

The sniper is a selected soldier who is a trained marksman and observer; who can locate and report on an enemy, however well hidden: who can stalk or lie in wait unseen and kill with one shot. The sniper is of immense value in war. However, the art of sniping is merely an extension of infantry skills developed to a specialist standard.

Australian Manual of Land Warfare, Part 2, Vol. 3, Pam. 5, Sniping, 1980

Reintroduction of sniping in the Australian Army

Following the end of the Vietnam War, Australia’s strategic defence posture changed to one of continental defence, with the government of the day making it clear that the primary role of the Australian armed forces was the defence of Australia, its offshore territories and vital interests. As a consequence the Australian Army took a heightened interest in conventional warfare, including sniping. This led to several changes in the late 1970s that influenced the attitude to sniping. The first was the development of sniping doctrine which brought together many of the lessons from previous wars, including Australian, British, American and even German and Japanese sniper experience. Second, the restructure of the Army saw the inclusion of a reconnaissance and surveillance platoon in each infantry battalion and the creation of a sniper team of six (three pairs). Finally, formal sniper training commenced at the Infantry Centre in Singleton to train the snipers now required by the battalions.

The reintroduction of sniping was not without controversy. A number of infantry officers, including battalion commanding officers, believed that the emphasis should be on improving marksmanship rather than ‘wasting resources on sniping’. Even as late as 1981 some ambivalence, if not resistance, remained within The Royal Australian Regiment. In August of that year Major General R.A. Grey, then General Officer Commanding Field Force Command, re-circulated for comment a document he wrote in 1972 entitled ‘Infantry Lessons from Vietnam’. Only two of the infantry battalion commanding officers commented on the section recommending the reintroduction of sniping, one of whom wrote that he was ‘not convinced’. Nevertheless, Major General Grey concluded that ‘All COs felt most strongly that it was time to review the art.’ The decision was made. Sniping was here to stay.

The first sniper course run by the Infantry Centre at Singleton in September 1976. Note that the rifle at this time was the SMLE No. 1 Mk. III* HT (image courtesy of Russell Linwood).

The task of designing and conducting Australia’s first sniper course since 1944 was assigned to a young infantry captain, Russell Linwood. Captain Linwood was appointed the Officer in Charge of the Small Arms Wing at the Infantry Centre at the beginning of 1976, and was given a very clear directive to ‘get the first course up and running before the end of the year’. The course was based on existing British and US military sniping doctrine, with the course syllabus designed around the British Army course. Of the eight wing instructors, two had recent sniper training overseas and the two foreign non-commissioned officer instructors, from the United States and Britain, also had some sniper experience. Russell Linwood described the course he designed:

The course took five weeks and used the SMLE No. 1 Mk. III (HT) sniper rifle, which was drawn from war reserve stocks. It was only an interim weapon pending formal trials to select a more capable weapon system. To complete the sniper system, the WWII Scout Regiment Telescope, standard issue binoculars and compass, and homemade Yowie suits were the order of the day. Ammunition comprised 1940 vintage Vickers machine gun belted ball from Pakistan which demonstrated low ballistic consistency until local purchase of more recent Australian-made .303 ball improved accuracy. While modern snipers can call upon a range of technical support devices, snipers of the seventies judged distance, read wind, engaged targets at night without night vision devices and walked and stalked to and from their engagements.

Students of the 1977 sniper course emerge from the woods in their home-made Yowie suits (image courtesy of Russell Linwood).

By today’s standards the course was unsophisticated: First World War rifles, mismatching telescopic sights, poor ammunition, surplus First and Second World War ancillary equipment and instructors learning along with the students. However, it was a start and the course developed quickly. Private Gary Smith attended one of the first sniper courses, commenting that:

There were about eighteen on my course, but only about eight passed. I was lucky to get a new rifle; it was made in 1916. It had been converted to a No. 1 Mk. III* HT but we received our rifles and scopes separately, and I don’t recall anyone getting their scope and rifle numbers to match. We also had both low and high scope mounts, the ability to add an adjustable cheek pad, a WWII Scout Regiment Telescope and WWI breech and muzzle covers – but all in good condition. At the end of the course I was able to take my rifle back to my battalion, 6 RAR. We also had the ability then to play around with any spare HTs in the armoury, such as cutting back the wood, drilling out the end cap, etc.

Within just a few years the course had advanced significantly. Brian Manns was a sergeant instructor on sniper courses at the School of Infantry between 1982 and 1984 and noted that:

We normally ran two courses each year, each of about ten to fifteen students and divided into three squads with a warrant officer and a sergeant instructor per squad. The training was physically very demanding and high standards were expected, as a result the failure rate was above 50%. Besides the students having to be good shots, they also had to be mature and become experts in fieldcraft, observation, navigation, stalking and the use of hides. In regards to marksmanship, they had to be able to successfully engage targets out to 600 metres, and to hit a man-sized target at 900 metres. The staff put them [the students] under a lot of pressure to simulate combat operations and some simply couldn’t take it.

The need for a new sniper rifle

During the Malayan Emergency the Australian Army trialled and introduced a new rifle, finally replacing the SMLE as its standard infantry rifle. The new rifle was almost identical to the British Army’s L1A1 SLR, which had been introduced into British service in 1954. Britain had produced its own variant of the Belgian FN FAL rifle under licence, and the Australian version of the SLR was similarly produced under license in Australia by the Lithgow Small Arms Factory from 1959. It proved a reliable, accurate and hard-hitting 7.62 mm semi-automatic rifle and remained the Australian Army’s service rifle until replaced by the F88 Austeyr, a variant of the Austrian Steyr AUG, in the early 1990s.

An experimental sniper variant of the Australian L1A1 SLR fitted with a Trilux optical sight manufactured at the Lithgow Small Arms Factory in 1959 (AWM REL07318).

While considered highly suitable as a standard infantry rifle, the SLR proved difficult to adapt as a sniper rifle. The sliding top cover over the receiver, and the way the rifle hinged (broke open) when stripping, made it difficult to fit a telescopic sight and the ‘high and wide’ way in which a case was ejected from the rifle after each shot had the potential to betray the sniper’s position. Regardless of these shortcomings, the Lithgow Small Arms Factory conducted numerous tests and trials of sniper variants, but with limited success. In addition, at least one of the Australian infantry battalions, 5 RAR, also trialled an SLR with a scope attached as a marksman rifle in Vietnam. However, user reports indicated that it was almost impossible to maintain zero. During the Vietnam War this was not a particular problem as the Australian Army’s concept of operations for jungle warfare after 1945 eschewed sniping. But with the return to conventional warfare in the 1970s, and the reintroduction of sniping into the infantry battalions, a new sniper rifle was required; the old SMLE No. 1 Mk. III* (HT) had served the Australian Army well, but by the 1970s the sniper variants were literally worn out and the telescopic sights of First World War vintage. A new sniper system was clearly required.

Australia was not alone in its search for a replacement sniper rifle; Britain, Canada, New Zealand and the United States were also reviewing their sniper systems. In the late 1970s the Australian Army trialled several sniper rifles to replace the aging SMLE No. 1 Mk. III* (HT). Contenders included the Steyr-Mannlicher Model SSG 69, Mauser Model 66 SP, Heckler and Koch G3 and the Parker Hale Model 82. Three of each of these rifles were purchased for the purposes of the evaluation. Thirteen telescopic sight systems were also tested, consisting of several of each of the Kahles Wien Helia Super ZF69, fitted to the Steyr Mannlicher SSG; the Kahles Helia Super 39, provided with the Parker Hale M82; the Zeiss Diavari – DA, with the Heckler and Koch G3; the Hensoldt-Wetzler, also provided for use on the Heckler and Koch G3; and the Zeiss Diavari – ZA with the Mauser Model 66.

Following extensive testing by the Defence Science and Technology Organisation’s Trials Division throughout 1978, the final trial report assessed that the:

Parker Hale … 7.62 mm NATO, rifle and iron attachable vernier scale sight together with the Kahles ZF69 Telescopic Sight, with range adjustment out to 900 metres, would most nearly satisfy the AMR [Army Materiel Requirements].

Some contemporary reporting suggested that a number of the other trial rifles actually performed better than the Parker Hale but were not chosen due to cost and delivery issues. However the Final Trials Report indicates that this is clearly incorrect; the Parker Hale out-performed all other contenders across the spectrum of the field and firing tests. Despite this, it was not a perfect fit. Changes to the magazine were required to eliminate misfeeds, the telescopic mounting points were not properly aligned to the axis of the bore and the telescopic sight system provided with the rifle did not perform well. In the end, the Parker Hale M82, matched with the Kahles Helia ZF69, was introduced into service in the Australian Army in 1979.

Designated the L3 in Australian service, the M82 was a variant of a sporting rifle, used the reliable Mauser bolt system in conjunction with a heavy free-floating barrel (1200 TX) and was chambered for the standard 7.62 x 51mm NATO round. It had an integral four-round magazine, an adjustable trigger and was able to attach a bipod, night vision device and sound suppressor. Canada was the first to adopt the M82, with Australia and New Zealand following. With the United States already using a variety of specialist sniper rifles or adapted sporting rifles such as the Remington M40, this period saw a move away from modifying existing service rifles for sniper use. Sniping was recognised as a specialist art that required specialist equipment.

The introduction of the Parker Hale sniper system, which was widely publicised throughout the Army at the time, generated renewed interest in sniping. Capitalising on this interest, the Australian Army Rifle Association was quick to organise competitive sniping matches. Initially, a trophy match known as ‘The Sniper’ was initiated for ADF sniper pairs as part of the annual Australian Army Skill at Arms Meeting (AASAM). This was later renamed ‘The Billy Sing’ after Australia’s famous Gallipoli sniper, Trooper Billy Sing of the 5th Light Horse Regiment. The match continues today using service-issued sniper equipment and with each competing pair firing and observing in turn. Sniping became so popular at AASAM that a second match had to be organised for non-sniper qualified competitors. This match, named ‘The Linwood’, was contested by international shooters and ADF personnel using any weapon of choice and firing alongside The Billy Sing competitors. Just as the popularity of rifle shooting competitions in early twentieth century helped prepare a generation of young men for infantry service in the First World War, so these two sniper competitions played a vital role in developing and maintaining both shooting standards and interest in modern service sniping.

A sniper pair on exercise at the Singleton Army range. The taller sniper is carrying a US-made 5.56 mm M16A1 rifle. The other holds a Parker Hale M82 (image courtesy of Russell Linwood).

Australian sniper rifle

7.62 mm Parker Hale Model 82

The Parker Hale M82 sniper rifle was introduced into the Australian Army in 1978, replacing the long-serving SMLE No. 1 Mk. III* HT (AUST). The M82 was equipped with a six-power Kahles-Helia telescopic sight (AWM REL19223.001).

Following the Vietnam War (1962–75), Australia’s strategic defence posture changed to one of continental defence. This heralded renewed interest in conventional warfare, including sniping, and signalled a requirement to replace the aging SMLE No. 1 Mk. III* (HT) sniper rifle. Extensive testing in the late 1970s resulted in the introduction of the Parker Hale 7.62 mm Model 82 (M82) sniper rifle from 1978. Designated the L3 in Australia, and fitted with a six-power Kahles-Helia ZF69 scope, it was essentially a military version of the Parker Hale 1200TX target rifle. The rifle was also used by both the Canadian and New Zealand armies.

The M82 was a 7.62 mm rifle which used the strong and proven Mauser action with a fully floating 1200TX heavy barrel. The Kahles Helia ZF60 6 x 42 scope was graduated to 800 metres and used a Number 7 reticule (cross-hair) pattern. Weighing less than six kilograms, the M82 was finished with non-reflective black metal, one-piece epoxy resin-coated wooden furniture, and an adjustable butt. There was no provision for a bayonet and it had a magazine capacity of four rounds. While a competent weapon, it was not sufficiently rugged for military service and was eventually replaced in the late 1990s by the SR-98, an Australian variant of the bolt action Accuracy International Arctic Warfare Rifle.

The Parker Hale M82 was used by some of the battalions deployed to serve as the Rifle Company Butterworth in Malaysia and also by 1 RAR snipers on deployment to Somalia on Operation Solace in 1993.

Operation Solace – Somalia (December 1992 to May 1993)

In the early 1990s a prolonged drought and civil war led to a complete breakdown of civil order in the African nation of Somalia. Television images beamed to the homes of Western first world countries of starving mothers and children, militia gangs hijacking relief convoys and armed bandits preying on poor villagers, prompted the United Nations to mount a large-scale humanitarian effort known as the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM I). A complete lack of cooperation from rival warlords and the continued hijacking and looting of UNOSOM supplies, along with attacks on UN personnel and vehicles, eventually saw the UN Security Council authorise the use of ‘all necessary means to establish as soon as possible a secure environment for humanitarian relief operations in Somalia’.

In December 1992, the United States accepted responsibility for the formation of a Unified Task Force (UNITAF) to support the United Nations’ humanitarian effort. Australia committed a 1000-strong military force based on 1 RAR. Under the codename Operation Solace, the Australians were allocated the Baidoa Humanitarian Relief Sector, in south-central Somalia, some 240 kilometres from the capital, Mogadishu. The 1 RAR group, including a sniper team, deployed in January 1993 for a four-month mission.

In the planning for Operation Solace, Defence assessed the likely threats to the force. This review highlighted sniper fire as one of the highest threat risks, particularly given that much of 1 RAR’s work would be high visibility ‘policing’ on foot in a built-up, urban environment. As Bob Breen wrote in his 2008 paper The World Looking Over their Shoulders, ‘The Australian Government had now sent one thousand of its young men and a small group of women into this violent, impoverished society where every male over the age of twelve either carried or had access to a gun.’ The very real danger of this situation would be highlighted by US experience in the Battle of Mogadishu later in 1993.

The most common weapon encountered by the Australians in Somalia was the prolific AK-47 assault rifle (AHU image).

For the Australian Army the issue became how best to address and minimise this threat. In part, this could be done by training. However, as confirmation of the task did not occur until 15 December 1992, and the troops would be arriving in Somalia from 14 January 1993, there was little time for pre-deployment training. What time was available was used for briefings, range practices and other preparation. The troops were briefed and practised in identifying the tell-tale signs of sniper activity such as villages or areas of the town suddenly devoid of any human activity or disturbance among local wildlife. The infantry companies also practised counter-sniper routines, with the soldiers learning to constantly scan for likely sniper hiding spots and to always move while covered by other members of the patrol.

While the establishment for battalion snipers in the early 1990s was for a section of nine — one sergeant and four sniper pairs — postings, promotions and courses meant that the 1 RAR sniper team deployed on Operation Solace with only seven (Sergeant Nayda, Corporal Mortimer, Lance Corporal Loftus and Privates Ahmelman, Cridland, Maitland and Seath). Strict limits on the number of personnel who could be deployed and the constant changing of priorities also worked against the deployment of a complete sniper section.

The snipers were equipped with the new standard infantry rifle, the Steyr F88, and the Parker Hale Sniper System. Robert Maitland was a member of the sniper section and considered that, while the Parker Hale rifle was ‘getting a bit long in the tooth by 93’,

… it was still a good rifle. Basically a heavy barreled sporting rifle with a Mauser-type action with a rotating bolt and three lugs that locked into the receiver. The heavy barrel was free-floating and the trigger fully adjustable for weight and pull. The Kahles was a six-power, fine crosshair scope set in 100 metre increments out to 800 metres and was a vast improvement on the old scopes our snipers used [such as the SMLE HT’s P18 scope]. While we used standard [7.62mm] ball ammo, it was factory selected for use by snipers so we considered it match grade.

Sergeant Lance Nayda was less enthusiastic, regarding the Parker Hale’s performance as simply ‘adequate for the task’. Nayda highlighted the weapon’s deficiencies such as poor stock design and composition, bedding issues with the barrel, maintenance and spare parts, and an inability to fit any form of night vision device. As there was no time to refurbish their Parker Hale M82 rifles, the sniper section was given approval to take a modified Mauser Model 98 rifle with them. This was a contemporary commercial version of the World War II German service rifle, the K98k. Known as the Mastin Sniper Special (MSS), these rifles were handcrafted by Phil Mastin, an Australian master gunsmith operating near Townsville in Far North Queensland. The MSS used the Mauser Mk. 10 action, a fully-floating Schultz and Larson barrel, standard military 7.62 mm ammunition and was fitted with the same Kahles Helia ZF69 telescopic sight used by the Parker Hale. According to Darren Mortimer:

The stock was laminated with around 17 layers of marine ply. Apart from being new and meticulously handmade, it had the advantage of being truly ergonomic and quickly adjustable to the sniper’s firing position. Both the cheek piece and butt length could be quickly manipulated. Unlike the Parker Hale which was fixed, the MSS could be adjusted with butt spaces although this required additional breaking down to complete. All in all, it was a good rifle but like all sporting rifles of that period it wasn’t really ‘field friendly’.

The MSS rifle taken to Somalia was privately purchased by the sniper team. It handled and shot remarkably similar to the Parker Hale, although the newer barrel afforded improved groupings.

In addition to their aging Parker Hale sniper rifles, the 1 RAR snipers received approval to deploy with a Mauser Sniper System (MSS) rifle, which was similar in appearance to the Mauser M98 shown here. The MSS was equipped with a service Kahles Helia ZF69 telescopic sight scope. The rifle was privately purchased by section members (Wikipedia Commons image).

Apart from their weapons, the snipers were also equipped with a limited number of night vision goggles, the ANPAS 5 goggles, disparagingly described as ‘a square brick that was strapped to your face’. There were also some night vision scopes available, although these would only fit the F88 Steyr rifles. All these night vision devices were in short supply and were thus held at battalion level and allocated on a priority basis. They were also characterised by a number of limitations which affected patrolling: ‘After wearing them for an hour and changing over the scouting position, you patrolled at the rear for the next 30 minutes as you were blind to what was going on until the eyes re-adjusted.’ Importantly, there were insufficient night vision devices for the snipers to operate effectively as a team at night. However, ‘after assisting to protect the US Air Traffic Control Tower at Baidoa airport from an attack, the Americans would lend us some state of the art night vision devices when we needed them’.

The sniper section was initially broken into pairs and allocated to rifle companies. Rob Maitland explained that:

We were often farmed-out to the rifle companies in one or two pairs. But we would surge with all three pairs into one particular company AO [area of operations] to cover tracks at night, identify enemy infiltration routes, over-watch a suspect’s location, or baby-sit NGO [non-government organisation] compounds when our intelligence suggested a possible threat.

Allocated in this way, their main task became manning a series of overwatch positions in the Baidoa town area to protect the NGOs providing humanitarian support, and on the approaches to town to watch for the movement of armed men. Other tasks soon emerged, including escorting food convoys, providing overwatch for food distribution points, and acting as bodyguards for VIPs and specialist NGO personnel such as the surgeons working on emergency cases, and even supporting American snipers at the US Embassy in Mogadishu, which one sniper described as ‘great fun’. The wide variety of tasks they performed soon began to test their pre-deployment training. For example, it became apparent that winning the trust and confidence of the local population was essential for the snipers to do their job. As Rob Maitland commented, ‘this was not something that was covered in the pre-deployment training’.

The local population was a vital source of human intelligence (HUMINT). They knew what was going on both in Baidoa and in the surrounding villages, and were well-informed on the location of bandits, on strangers who may have moved through the area recently or on any other suspicious activity. These reports often helped the sniper team determine where to establish observation posts and led to the arrest of several wanted or suspected war criminals. Sergeant Lance Nayda, 1 RAR’s sniper supervisor, recalled that they found a unique way to persuade the locals to chat. Knowing that ‘the Somali understands and respects force’, the snipers demonstrated their shooting prowess to the villagers and town residents by killing stray dogs that were considered pests and a health risk by the local population. Rob Maitland added that ‘many of the dogs were diseased, had been feeding on corpses and rabies was a problem’. Lance Nayda commented that:

… it was a chore that had a number of positive sides: for one it gave the snipers confirmation of their rifles’ zero without the need for a zeroing practice. If the firer aimed and hit the dog in the head that was good enough and that was what happened 99 per cent of the time. … When they observe a sniper kill a dog with one shot at 400 metres, it gives the locals confidence that the soldier with the long rifle and paint on his face can protect them if necessary.

While the overwatch tasks produced some results, and could become interesting when the snipers were spotted and fired on, the Rules of Engagement for the force did not permit ambushes; the snipers could only fire in self-defence or to save another’s life. This made the surveillance work very tedious and boring; the snipers felt that their skills could be utilised to better effect on patrols and moving among the local populace collecting intelligence. In late January the two snipers attached to Major Adrian Blumer’s D Company suggested that a four-man sniper patrol be trialled. Sniper Corporal Darren Mortimer believed that the sniper’s training in moving stealthily made him the ideal person to track and arrest some of the bandits who had been raping and stealing from women at the water points around town. Major Blumer had been posted to the Canadian sniper school and had an excellent appreciation of what snipers could do. Lance Nayda considered that, of the 1 RAR company commanders, Major Blumer was the one most prepared to listen to the snipers and to work with them on appropriate tasks that could help him achieve his and his company’s objectives. That same night, at around 10.40 pm, Darren Mortimer and three other snipers infiltrated one of the water points. Lance Nayda explained what happened:

One of the snipers was acting as scout and carrying a Steyr. He came around a corner and there were four or five armed bandits coming towards the patrol. The scout [Lance Corporal Darren Loftus] challenged the lead bandit who then put his rifle to his shoulder and pointed it at the scout. The scout, who was wearing night-vision goggles at the time, fired at the bandit shooting instinctively from the waist. The automatic burst killed the bandit instantly. The fire initiated a contact which resulted in the bandits shooting through. I went back and measured the distance from the muzzle of the scout’s rifle to where the bandit fell. It was just 15 paces. He had no time to think about it at all, it was purely instinctive.

The Company Commander, Major Blumer, under whose authority the patrol had been conducted, later recorded in his war diary that the incident ‘was fairly conclusive’.

Apart from their sniper rifles, the 1 RAR snipers also used the standard Australian infantry rifle at the time, the F88 Austeyr. Note that these earlier versions of the rifle did not contain the MILSTD 1913 Picatinny rail system that was added later to accommodate a variety of optical devices and accessories (AHU image).

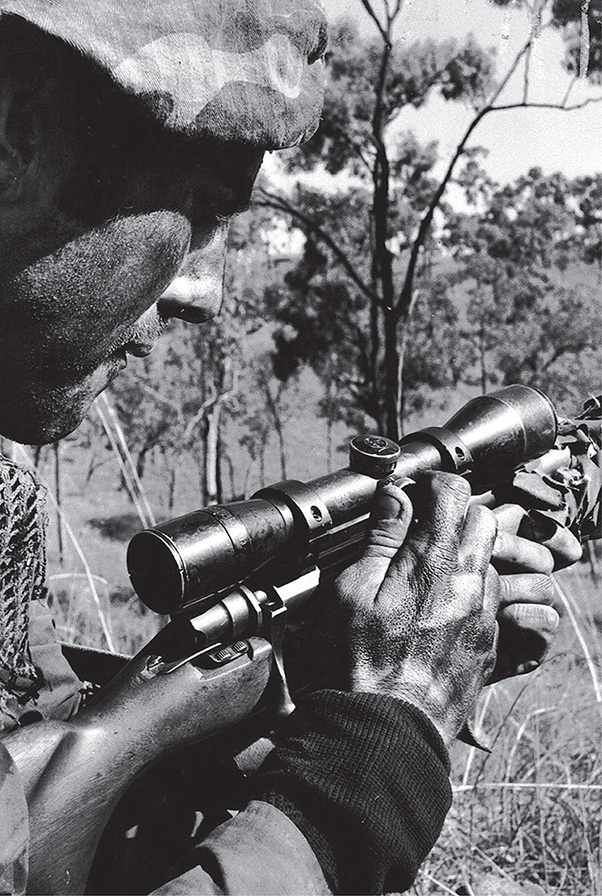

This image shows a 1 RAR sniper established in a hide on the outskirts of Baidoa with a Parker Hale M82 sniper rifle (AWM P01735_414).

Following this engagement the snipers began to spend more time out with the companies, including lengthy patrols into the surrounding countryside to help curb banditry. In this way they became familiar with community leaders in the towns and gradually gained their trust, enabling them to gather HUMINT on the movement of bandit groups. These patrols worked to both detect armed groups and deter them from entering either the villages or Baidoa. As the Rules of Engagement restricted the circumstances under which the snipers could fire their weapons, they remained alert to ways they could support the battalion. One unusual idea involved three of the snipers dressing as locals and ‘just hanging out in a busy street’ near a suspected war criminal’s house with the intention of confirming his identity and location. If they could achieve this the house could then be raided and the suspect arrested. However the battalion commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Dave Hurley (later Chief of the Defence Force), cancelled the operation, concerned that it may have contravened the Rules of Engagement. Not to be deterred, the snipers found another way to ascertain the identity of the wanted man. A sniper pair established themselves in a hide overlooking the suspect’s house. One of the snipers had attached a 35 mm camera to his telescope and was able to capture the man on film. He was subsequently arrested and tried for crimes against humanity.

A 1 RAR sniper serving with the Australian contingent to the Unified Task Force in Somalia (UNITAF) with a camouflaged Parker Hale M82 sniper rifle and wearing a Yowie suit. These suits were only suitable for use in the countryside (AWM P01735_497).

The Australians learned a great deal from this deployment and it informed the future development of the Army generally, and sniper doctrine and equipment in particular. Rob Maitland observed that ‘While we had fairly good training prior to embarking, we could have prepared better for working in built-up areas.’ In the lessons learned study conducted following 1 RAR’s return to Australia, Lieutenant Colonel Hurley also identified military operations in urban terrain (MOUT) as one of the key training deficiencies. This eventually led to the creation of a MOUT training facility for the ADF. Over the next decade the lessons from Somalia led directly to an influx of new equipment that significantly assisted the sniper. Procurements such as third generation night vision devices, Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite navigation systems, lightweight radios, new weapon sights, surveillance equipment, and even a new sniper rifle system all contributed to increasing the deadly effectiveness of the sniper.

The changes were not all about hardware. Sergeant Nayda and his 1 RAR sniper team provided important feedback to the Infantry Centre which influenced the development of sniper doctrine and training. Rob Maitland, a long-serving sniper and currently a battalion company sergeant major, strongly believes that, in over 20 years of involvement in sniping, he has seen the art come a long way:

We thought we knew it all when we deployed to Somalia, but we were amateurs by today’s standards. Our training today is first class. I’d rate us against the top snipers in the world, including Britain, US and Canada. And our Advanced Sniper Team Leader course has to be the best in the world. … Operations in Timor, Iraq & the Ghan [Afghanistan] have provided many lessons and assisted in allowing us to develop further doctrine, course TMPs [training management plans] and identify more suitable equipment. At times the only difference between us and other countries’ snipers has been our lesser quality equipment. In the past five years even this has changed.

Replacing the Parker Hale

While the SMLE No. 1 Mk. III* (HT) served the Army for 35 years, primarily because little sniping was conducted by the Australian Army over this period, the Parker Hale was close to the end of its life after just 13 years. By 1992 it was in need of constant upgrade and maintenance. In addition, operational feedback from Somalia highlighted several deficiencies in the weapon system. The rifle’s wood swelled when wet, adversely affecting its zero; it lacked a bipod and a bridge mount for solidly mating the scope, and it was difficult to fit a broad range of optical devices; its four-round magazine capacity was considered insufficient for effective combat shooting; and the system’s target acquisition and surveillance performance was below that required on the battlefield, particularly in MOUT operations.

A 1 RAR sniper on exercise in 1981. While only two years old, this Parker Hale is already showing signs of wear (image courtesy of Russell Linwood).

That the Australian Army was in need of a replacement sniper system after such a short period in comparison with the length of service of the SMLE No. 1 Mk. III* (HT) was largely due to the new emphasis on sniping and, consequently, the extensive use of the weapon system. A number of experienced users of the Parker Hale sniper rifle, such as sniping instructor Sergeant Brian Manns, believed that this high level of wear was due to the fact that the rifle was ‘basically a sporting shooter’s rifle’. Unlike previous sniper rifles, such as the SMLE variant, which were based on ruggedised and proven military rifles, the Parker Hale was a civilian precision instrument. It did not possess the field survivability necessary for military combat shooting.

With feedback on the performance of the Parker Hale Sniper System from Operation Solace, the Army began to consider a replacement program. However, the Somali operation had highlighted a number of equipment deficiencies and defects, all of which needed addressing. A new sniping system would have to wait until the late 1990s when a formal trials program was run, leading to the selection of Accuracy International’s Arctic Warfare sniper rifle system, known as the Aust SR-98, for service in Australia. As the SR-98 is still in service with the Australian Army, the details of its selection remain classified. Suffice to say, the SR-98 was the best performing sniper system in the trials and was introduced into service in 1998. Manufactured under license by Thales Australia, it is a magazine-fed, bolt-action, manually operated rifle fitted with a German-made Schmidt & Bender, three to 12-power telescopic sight secured by a fixed mount on a Picatinny rail. Iron sights are supplied in the complete equipment schedule as an emergency back-up system and can be fitted should the telescopic sight be damaged. The SR-98 can also be equipped with a screw-on suppressor to reduce muzzle flash and firing signature.

A sniper and his observer from 3 RAR train on the Aus SR-98 sniper system (Army Public Relations image).

The Australian sniper rifle SR-98

A sniper trains on the range with an SR-98 while wearing an NBC mask (AHU image).

Initially produced by British company Accuracy International, the Precision Marksman (PM) sniper rifle was first introduced into military service by the British Army in 1982 (designated the L96A1). An upgraded variant of the PM rifle was developed in the early 1990s and marketed as the Arctic Warfare (AW) series. It was a variant of this AW rifle that the Australian Army chose to replace its existing Parker Hale Model M82 sniper rifle in the late 1990s. Known as the Aust SR-98 and manufactured under licence by Thales Australia, it is a magazine-fed (ten-shot capacity), bolt-action, manually operated rifle chambering a 7.62 x 51 mm round. It is on issue to infantry battalion snipers and has been used on most deployments, including East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan, since its introduction. The rifle is paired with a German-made Schmidt and Bender 3-12 power telescopic sight secured by a fixed mount on a Picatinny rail. The Schmidt and Bender scope that was originally issued with the SR-98 had a swing arm tension mount. However it was quickly discovered that, when the sniper crawled forward, the scope could easily catch on vegetation and detach from the rifle. A parallax drum was added to the sight as well as a screw-on suppressor to reduce muzzle flash and firing signature. Iron sights are supplied in the complete equipment schedule as an emergency back-up system and can be fitted should the telescopic sight be damaged.

The stainless steel free-floating barrel also sports a muzzle brake to reduce recoil and flash. Further enhancements include a bipod, cheek comb and butt-spike, making the SR-98 well-designed, easy to use and simple to maintain. It has an advertised ‘effective range’ of 800 metres, although trained snipers can reliably extend this distance. The attached Schmidt and Bender telescopic sight is the most common sniper rifle scope in use by the Australian Army.

Operation Astute – East Timor [September 1999 – February 2001 (key period)]

We don’t need a large support structure, a lot of men or money to get the job done. The sniper is, beyond any element of a doubt, the most cost-effective weapon on the battlefield today.

Sergeant Lance Nayda, Sniper, 1 RAR, 1995

At the end of August 1999, the people of East Timor voted overwhelmingly to become an independent state rather than remaining part of Indonesia. Almost immediately armed militia groups and rebellious Indonesian troops launched reprisals against pro-independence supporters while the Indonesian military and police stood by. Buildings were burned, stores sacked, facilities destroyed and the local population attacked, murdered, raped and left generally fearing for their lives. In September 1999 Australia accepted a request from the United Nations to lead a multinational force to restore order. Known as the International Force East Timor (INTERFET), the first troops began to arrive in the capital, Dili, on 20 September. By the end of the following month INTERFET consisted of some 9900 troops from 16 nations. Australia’s contribution totalled 5570, including three infantry battalions (2 RAR, 3 RAR and 5/7 RAR), a Special Air Service (SAS) squadron and commando sub-units from 4 RAR, which was then in the process of converting to a commando battalion.

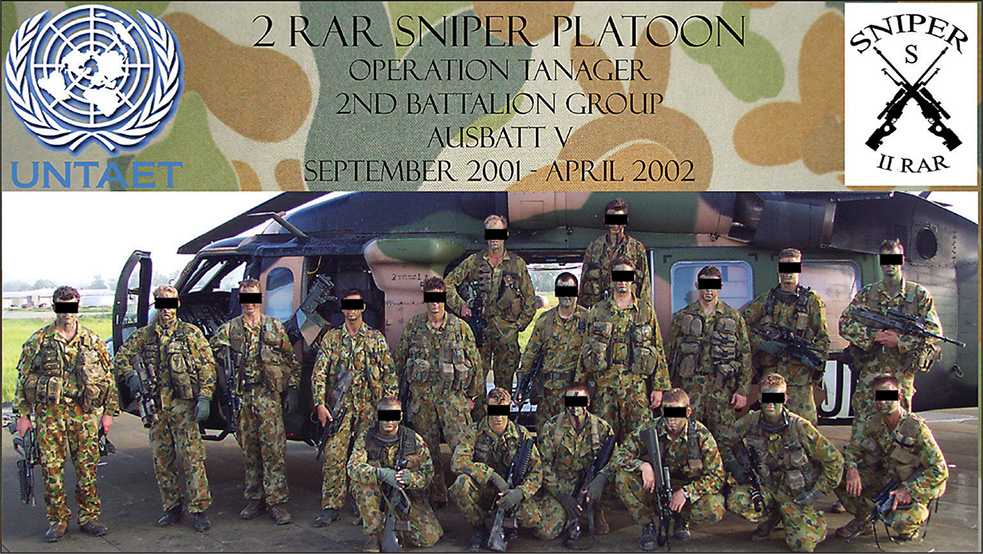

The 2 RAR sniper team in East Timor, September 2001. Note that the men are carrying the F88 Austeyr rifle, including some fitted with a 40 mm grenade launcher attachment (image courtesy of Jason X).

Within a few weeks, 2 RAR and 3 RAR, supported by a contingent of Special Forces, had taken control of both Dili and key regional areas. They had also pushed out to the border of East and West Timor, leaving 5/7 RAR to maintain security in Dili. Over the next 12 months, as more troops arrived and the cycle of unit relief occurred as troops completed a six-month tour of duty, a key task was controlling the border to prevent militia groups and Indonesian soldiers infiltrating into East Timor. The infantry battalions, supported by light armour and helicopters, conducted extensive patrolling in an attempt to detect border crossings and to intercept those groups that did cross. Small patrol-level firefights occurred, including attempted ambushes and the use of grenades against the Australians by armed militia groups, although the anti-democracy militias and renegade Indonesian forces generally tried to avoid a direct clash with the ADF. While the last armed conflict occurred in February 2001, active patrolling continued into 2003 with the emphasis gradually shifting towards civil-military cooperation and support for NGOs and infrastructure programs throughout East Timor.

The Army’s operations in East Timor placed enormous pressure on The Royal Australian Regiment, with over half of Australia’s regular infantrymen on operations there in the early period of the deployment. This was further complicated by the fact that only a few of the regular battalions were at full strength in late 1999. One battalion, 4 RAR, was converting to a commando role and another, 6 RAR, was an under-strength composite Regular-Reserve battalion. In addition, each of the battalions was further denuded of manpower by the normal routine of leave, training and promotion courses, and illness. While the battalions were increased to almost full strength by an infusion of Army Reservists, this was not the case for the battalion snipers. The battalion sniper establishment at this time was a sniper section of 13 — one sergeant supervisor and six sniper pairs — and the training requirement for a sniper to be effective was well beyond the reach of a part-time Reservist.

Some of the battalion commanding officers allowed their sniper sections to hold members above their establishment. For example, during the 1990s, 1 and 2 RAR sniper sections would often exceed their normal establishment by holding men who had passed the sniper pre-selection course and had been detached to the sniper section for on-the-job training. The initial deployment of the sniper teams was not a problem; snipers who had been posted or promoted out to non-corps, headquarters or training positions quickly volunteered for active service. Once it was evident that Australia was in East Timor for the long haul, it became a different story. The snipers were pressed to provide full teams as their battalions returned for a second rotation.

Initially, most of the battalions integrated their sniper section into the battalion reconnaissance and surveillance platoon for deployment to East Timor, their tasks similar to those performed in Somalia several years earlier such as manning overwatch positions to collect intelligence and supporting vehicle checkpoints. While the sniper sections took their SR-98 sniper systems with them, the snipers who operated with the reconnaissance and surveillance platoons generally carried either a standard F88 Austeyr rifle or an F88 equipped with a 40 mm grenade launcher attachment. Some battalion snipers also carried an F88 with a Schmidt and Bender telescope. However, as also occurred in Somalia, the snipers soon requested a more active role and eventually became an integral part of each battalion’s patrol program, although providing overwatch surveillance and supporting vehicle checkpoints could be very boring and mundane. One sniper recalled that ‘these tasks were generally very monotonous and, over time, it could be hard to maintain your vigilance’. Nevertheless, there were times where even these monotonous tasks could become exciting.

An Australian Army sniper team practises rappelling from a helicopter in East Timor (image courtesy of Jason X).

Soon after their arrival in Dili, 2 RAR established a series of vehicle checkpoints to disarm and control the militia who were speeding through the towns intimidating the local populace. Apart from the infantry, each checkpoint was supported by Australian Light Armoured Vehicles (ASLAVs) armed with .50 calibre machine-guns, and a sniper pair. One night a convoy of around 600 armed members of a local territorial battalion unexpectedly arrived at one of the checkpoints. Annoyed at being forced to stop by the Australians, the territorials began to yell abuse at the Australians and raise their weapons. In response, the Australians adopted a defensive stance with the ASLAV’s gunners training their machine-guns on the group while the snipers, unseen by the angry mob but able to clearly view the territorial troops through their night vision goggles, began to prioritise their targets. Eventually the territorials were permitted to proceed, but it was a tense and close encounter that could have turned bloody at any point.

Throughout the battalions’ rotations through East Timor, each maintained observation posts to watch over key points along the border. These positions were usually close to border villages or border crossing points. The battalion snipers, with their specialist training, were often used to man some of the more remote covert observation posts. In May 2000, a sniper group from 6 RAR was tasked with establishing a covert observation post in East Timor opposite a displaced persons’ camp and temporary Indonesian Army barracks just inside West Timor. Their role was simply to observe and report any suspicious activity, such as attempted infiltration into East Timor. Sniper Corporal Steve Jerome and Private Jamie Moore, supported by Sergeant Stephen Brown, were dropped some distance from their operational area by helicopter. Taking several hours to stealthily infiltrate their observation post and locate a suitable hide, they were finally established by first light the following morning. With a team of three, the plan was for one to rest, another to observe and one to protect the hide.

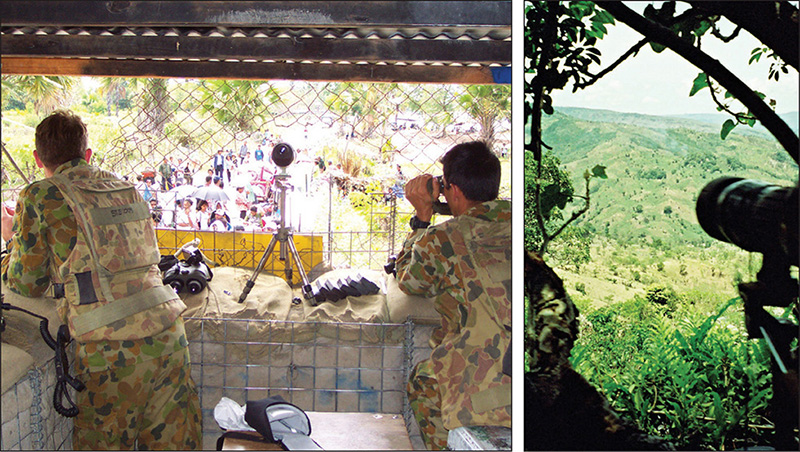

Two battalion observation posts: one is a covert sniper post near the East–West Timor border (right), the other a high-visibility post manned by 2 RAR within an East Timorese village. Note the chicken wire around this observation post, a measure adopted to prevent the lobbing of grenades and Molotov cocktails into the post (images courtesy of Jason X).

Early that morning a local villager and his dogs walked close to the hide and one of the dogs discovered the hidden snipers. When the dogs’ owner came to investigate what the animals were barking at, an awkward but short confrontation followed ending with the villager calling his dogs and walking off. Corporal Jerome had to weigh his options: should they remain in their current location, withdraw or relocate? He decided to stay put as their location afforded excellent observation into West Timor and the Indonesian camp. Within an hour of the incident with the dogs, Sergeant Brown heard the muffled sounds of someone attempting to stealthily approach their position. The direction of approach was along a very steep slope flanking their hide. Turning and kneeling slowly so as to better observe, he could make out the upper part of a person carrying a rifle and moving cautiously. The stranger was also wearing a red headband, suggesting that he was a member of a militia group. Adopting a firing position, Brown switched his rifle’s safety catch to ‘fire’ just as he heard other men close to the one he was observing. After a minute or so the man spotted Brown and raised his rifle to fire. Brown’s reaction was immediate and consistent with his training — he fired several short bursts, hitting the man and quickly moving back into the hide and cover. As he moved he heard other men, behind the one he had fired at, doing the same. What he did not hear was Jamie Moore also firing at the intruders.

Jerome and Moore had both also heard the sounds and assumed that they were being stalked. Moore engaged the man closest to Brown as soon as it was clear that the militiaman was about to open fire, while Jerome contacted his battalion headquarters and requested support. Once the initial engagement had ceased, a period of eerie quiet descended on the hide. According to author Bob Breen, ‘Brown and Jerome concluded that their visitors’ break contact drill was very professional.’ Jerome assessed that it was too risky to try to exfiltrate with an unknown number of armed men close to their position. His team had a commanding view of the area and Jerome believed that they could defend their position if they needed to. The Commanding Officer of 6 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Mick Moon, ordered an observation helicopter into the area immediately and warned out his battalion Ready Reaction Force to assist the snipers’ extraction and to photograph and gather evidence at the scene in preparation for the inevitable inquiry, and to rebut Indonesian propaganda alleging illegal actions by the Australians. On the arrival of support the area was swept, secured, inspected and photographed. While there was evidence that at least one man had been severely wounded, no bodies were located.

After a number of attacks by militia forces on relatively isolated Australian Army outposts, 6 RAR increased its level of patrolling, playing a cat and mouse game with the militia. Due to their specialist skills and tracking capabilities, members of the battalion’s reconnaissance and surveillance platoon, including snipers, became an integral part of the patrol program and contributed to the discovery of several well-concealed militia campsites within East Timor. On 6 August 2000, a patrol consisting of five men from the reconnaissance and surveillance platoon and four tracker-qualified snipers commanded by Corporal Nichols from the sniper section, were operating in the vicinity of Mount Leolaco. Shots had been heard and the patrol was investigating.

Helicopter resupply in East Timor. The terrain in East Timor presented its own unique challenges to the sniper in navigating, observing, infiltrating and shooting (image courtesy of Jason X).

While deployed close to what appeared to be a relatively well used track, the patrol observed an armed militiaman walking towards their concealed position. On being challenged the man quickly took cover and aimed his rifle at the patrol. The Australians opened fire but the gunman and another militiaman soon withdrew around the Australians’ position. Two of the snipers, Corporal Scott Beasley and Lance Corporal Troy Weston, managed only a ‘fleeting glimpse of both infiltrators’ and were unable to fire through the thick vegetation. They threw grenades but were unable to observe the men as they quickly withdrew. Around this time a second group of gunmen opened fire from another direction. Based on the disciplined and military manner in which the militia group responded, Corporal Nichols’ patrol had clearly surprised a similar-sized Indonesian-trained militia patrol. The engagement ended as the light faded and the armed infiltrators withdrew. The incident highlighted the fact that not all the infiltrators were poorly trained militiamen. The Australians needed to remain vigilant and prepare for a firefight. This Australian sniper group was left disappointed with the outcome. As highlighted by Bob Breen in his paper The World Looking Over Their Shoulders, ‘They [the snipers] had been unable to capitalise on the element of surprise and, despite observing and challenging the gunman, had missed hitting him at close range.’ One of the 6 RAR snipers indicated that, had they been using their SR-98 sniper rifles at the time — they were equipped instead with the Austeyr F88 rifle — ‘it would have been a different story’.

In addition to manning vehicle checkpoints and observation posts, a number of the battalion snipers were also involved in a wider variety of tasks which tested their training and marksmanship. For example, on 24 September 1999, in the first week of its deployment, the Australian 3rd Brigade launched a major show of force, conducting a massive sweep — effectively a cordon and search operation — across Dili. This sweep involved both of the 3rd Brigade’s infantry battalions and a company of attached Gurkhas supported by the ASLAVs and rotary wing aircraft. A number of the helicopters had snipers on board providing a mobile overwatch capability and a level of ‘surgical fire support’. One of the snipers in a Blackhawk helicopter that day considered this an unusual task and not one for which they had received recent training: ‘Firing from any moving platform is always a bit hairy, but these Blackhawks were flying low and fast, making target selection difficult enough … I’m glad I didn’t have to fire in close support of the guys on the ground.’

In another incident on 20 October 1999, 3 RAR responded to reports of militiamen crossing the border into East Timor and firing on Australian helicopters patrolling the border. A company-sized group from the battalion established itself on the border in a series of observation posts from which the Australians could observe the likely crossing points being used by the militia. They were in place and waiting by first light on 21 October when an Australian light observation helicopter flew along the border and, as expected, the militia engaged it. The Australians in one of the observation posts returned fire. However, the militia were firing from a position several hundred metres away from the waiting company and there were civilians in the area; consequently the Australians’ fire was relatively ineffective. The company commander brought forward a sniper pair to engage the militia. Using only the 5.56 mm Austeyr F88 rifle, the snipers initially missed their target, but were close enough for the militia to quickly retreat.

A sniper’s SR-98 and related equipment is laid out on the hut floor for a kit inspection prior to an operation in East Timor. The relatively new SR-98 was only rarely used in East Timor as the snipers operated more as a reconnaissance and surveillance force equipped with the Austeyr F88 (image courtesy of Jason X).

Snipers in East Timor were not restricted to the infantry battalions. Special Forces snipers and observers were also deployed in covert hides to watch border crossings or other special sites. These generally worked in two 4-man teams and could sub-divide into two-team pairs if necessary. While their routine varied, a typical operation comprised a two or three-day stint in a covert observation post with a similar time back at camp. They also provided a helicopter-borne overwatch capability and assisted in reconnoitering suitable hide and landing zone locations which were recorded on a database for use throughout the Australian area of operations.

East Timor highlighted how far the Australian Army’s sniping capability had developed since its reintroduction in the 1970s. In Somalia, the first operational test of the Army’s snipers since the Korean War, the battalion snipers had performed well. But this was arguably more the result of good leadership and the determination and initiative of individual snipers. In the several years that elapsed between the return of the 1 RAR group from Somalia and The Royal Australian Regiment’s commitment to East Timor the training, equipment and overall professionalism of Army’s snipers had advanced dramatically. In East Timor Australian snipers only rarely engaged the militia. In some ways they did not need to. Word spread rapidly that there were ‘men with long rifles’ among the Australian soldiers, an example of the powerful psychological effect that can be achieved through the mere presence or even threat of snipers on the battlefield.

Operational lessons learnt from Somalia were integrated into the snipers’ training program, both at the Infantry Centre and within each of the battalions and the Special Forces. Importantly, these lessons also assisted in the continued development of the snipers’ tactics, techniques and procedures, as reflected in new and revised doctrine. A new sniper system had also been delivered, and Project NINOX had provided the sniper with the ability to turn night into day through a range of soldier-carried image intensifier devices and thermal imagers. Over several years following the key period of the East Timor deployments, new sniper and marksman equipment was gradually introduced, including the 12.7 mm AW50F Anti-Materiel Rifle, 5.56 mm M4A1 Modular Weapon System, .338 inch Blaser Tactical 2 Sniper Rifle, 12.7 mm Barrett M82A1M Anti-Materiel Rifle and the 7.62 mm Mk 11 Mod 0 Rifle.

Some snipers have argued that the most valuable contribution to the development of the sniper capability in the Australian Army was the opportunity for commanders at all levels to see for themselves how snipers could be used as a combat force multiplier on operations. In Somalia a large part of Sergeant Lance Nayda’s job as the 1st Battalion’s sniper supervisor involved advising the battalion how to use its snipers, while the snipers themselves coped with a very sharp learning curve. By the time The Royal Australian Regiment deployed to East Timor, the battalion officers and senior non-commissioned officers understood how to employ their sniper section and the snipers themselves were confident in the tasks they were allocated. While it had taken almost 25 years from the time of its formal reintroduction, by 2002 sniping had finally reached the stage where it was not only accepted, but was a fully integrated element of the infantry battalion and Special Forces’ combat power. Operations were now planned that specifically incorporated sniping, or at least the unit’s snipers, in the overall tactical plan. Given that the last time this had occurred in the Australian Army was 1918, this marked an extraordinary and significant milestone.