Selling Your Origami Art

TRANSFORM CREATIVITY INTO CASH

BY ORIGAMIDO STUDIO COFOUNDER RICHARD L. ALEXANDER

Museums, as well as corporate and private buyers do purchase and collect folded art. Because origami art is in its infancy, and because several important advancements have been made by living origami artists, some of their works are highly collectable. As Michael has said, “I believe that art is the unique contribution that any individual can give to their chosen craft.”

Who is Buying?

Most of the private origami art collectors at this time are also folders who are excited to purchase works by the contemporary artists they admire. If you are an origami artist and want to sell your own expressive works, this discussion is meant to encourage you to proceed, but with some caution.

What is Selling?

We sell only works folded from Origamido handmade paper. With the exception of white watercolor cotton paper, we do not consider commercial papers to be archival. Nearly all of the pieces that we have sold are original designs folded by the creator / artist. We sell many more pieces mounted in deep wall frames (shadow boxes) than pedestal pieces. About half of the art that we sell is commissioned for a special occasion, such as a wedding or retirement gift. This adds the pressure of making several decisions about papers, colors, sizes, frames, poses… (and a deadline), so we prefer to make what we like and then sell our art “off the wall.”

Intellectual Property

For centuries, origami was just a craft. The most famous early example of a “how-to” origami book is Senbazuru Orikata, published first in 1797 in Japan. It offers instructions for making variations of the still-popular origami crane. The placement of each crease is straightforward, and when anyone followed the published diagrams to reproduce objects, they all looked essentially the same. With such a long history of people sharing their methods, folding and selling multiple copies of anonymously designed “traditional” paper crafts has created a problem for today’s expressive origami artists. At some point, the line between craft and art is crossed. Any artist may rightly feel infringed upon when others produce and sell copies of his or her original designs without first obtaining permission, which may include a license, with or without financial compensation. That line may seem fuzzy to the public, especially when so many origami designers publish instructions for others to replicate their creations.

There is an important relationship that exists between a creator and the other folders of his or her work. The lens that brings this relationship into focus is the copyright statement in the instructions (book, video or kit). As designers of original origami, we want anybody to freely enjoy the wonderful process of folding any of our designs for their personal enjoyment. Commercial use (selling objects or images of a designer’s works by anyone except the designer) is prohibited, unless and until the designer grants explicit written permission.

As with any expressive art, most origami artists never grant such permission to others. This longstanding policy certainly extends to our own Origamido Studio: I do not fold any of Michael’s designs for sale, nor he mine, without clearly stating so. For example, we co-folded a piece, called “Snap,” our second American Alligator, and this fact is clearly displayed on all of the printed attributions. We co-folded that model simply because each alligator takes us fifty hours of folding!

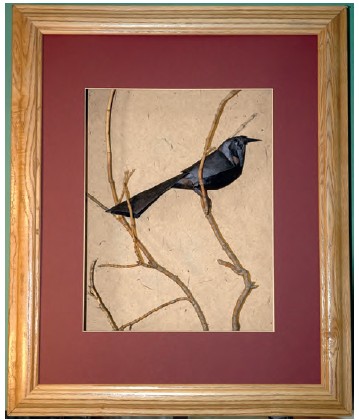

LaFosse’s “Flaxen Grackle,” protected by mounting in a deep frame, appeals to more buyers than if offered unframed.

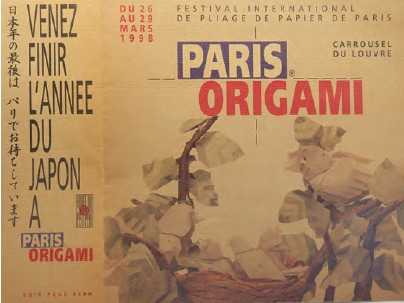

The late Eric Joisel organized a showing of remarkable folded artworks at the Carrousel du Louvre in 1998.

Unfortunately for artists and creators, the Internet has made a lawless Wild West of their intellectual property as portions of songs are “sampled,” and visual images are “shared.” Such use without the artist’s permission constitutes theft. The argument about where to draw the blurred line is sure to continue, but this erosion of intellectual property rights has had a disastrous impact on several of our brilliant origami-designing friends, some of whom have refused to ever publish again. We believe that the original artist must be allowed to control all uses of their own intellectual property, and that nobody should capitalize on the sale of even derivative works without the knowledge, consent and fair remuneration of the original artist. We believe that when somebody sees an original work of folded art offered for sale, the buyer should be able to safely assume that it was made by the hands of the original designer / artist.

There are origami-proficient fans of artful folders who somehow expect to be able to reproduce the works of a master and then put them up for sale. Imagine if Rembrandt or da Vinci produced paint-by-numbers kits for anybody to reproduce their masterworks! The technology of zoom-in video, and even “no-hands” 3-D animated tutorials enables artists to share much more information about how they shape their wet-folded creations artfully.

When professional musicians perform the works of a composer, they pay for that privilege. Our publisher pays us for the right to commercially reproduce and sell our intellectual property. When others unlawfully reproduce our work without such an arrangement it hurts our publisher’s sales, our commission and the value of our next book to the next publisher. Without a certain amount of financial success, no designer or artist can continue to share their new designs with the public.

Michael’s Origamido: Masterworks in Folded Paper (2000, Rockport Publishing) was the first book (that we know of) about origami art, presented essentially without instructions for reproducing the depicted works. Even so, the publisher was reluctant to take the plunge fully, and asked Michael to include a handful of diagrams so the reader could better appreciate what went into the works gracing the full color “coffee-table book” of full-page images. Many of the works depicted in this book were shown to the public at a 1998 exhibition at the Carousel du Louvre in Paris, France. This exhibition, organized by the late Eric Joisel, had run low on funds before a show catalog could be produced, and Rockport’s editors liked Michael’s idea of collecting images from fellow exhibitors for a reference work on the state of origami today.

Since origami artists take two-dimensional paper and convert it into three-dimensional sculptures, collecting it does require proper display and storage space. Artists and collectors alike often also possess huge collections of electronic images of works that they have seen at gatherings and conventions. These reside in digital files, since few could ever afford to purchase or display the actual pieces properly. The origami museum of the future probably exists now, albeit spread across disparate electronic collections on the Internet.

LaFosse finishes a bouquet of “Wedding Orchids” for a special bride.

Honolulu paper maker Allison Roscoe joyfully displays a freshly made sheet of premium abaca paper.

Value and Authenticity

As with any artwork, quality is the most important criteria used to establish value. Is the work folded of archival paper colored with fine art quality pigments? The documentation of the provenance of the piece, and the history of its creator, also impact the price. The fact that the methods and materials are available to the public also opens the unfortunate possibility of forgery. It is also important for the artist to stamp or sign and date a work intended for sale. At least for now, it is most common for collectors to become good friends of the artist producing works for their collection. We also videotape the process when we fold many of the works being sold in our gallery, which is another way of providing authenticity to the buyer. Michael began publishing his designs in 1984, and to date, he has contributed to more than eighty publications, so many of his signature pieces are well documented in those books. Photographs taken at public exhibitions and origami conventions augment the published history of Michael’s artistry.

To Sell, or Not to Sell…

You must be comfortable parting with your object. Yoshizawa said that he never sold a single piece because he considered them his children, whom one does not sell, and so he rented them out for advertising photography. One does not live forever, and if you do not sell your works, there will come a time when it might at least make sense to prescribe who should care for your treasures after you have passed. Will your life’s work burden your loved ones? Should you have sold them to the highest bidder, or to someone who could provide the best care?

Pricing

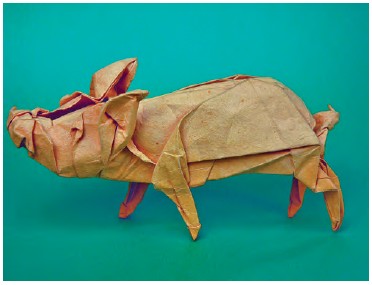

Students ask what they should charge for an original work. There are several ways to value art. First, we not only account for the costs of the time and materials, but also account for at least some the time invested in learning the craft and refining that specific design. The quality of the materials should impact the price. Small pieces are expected to cost less, even though any accomplished folder will tell you that they require more skill, finesse, time and patience. Large pieces are much more expensive to frame, and they require more “real estate” (wall space or pedestal space) for proper display, which limits the market to some extent. We would never sell a piece of our work as fine art if it were not folded from archival, fine-art quality materials that I am confident will last as long as any other work of fine art. This is the primary reason that we make our own papers from the finest fibers and pigments. While such handmade paper may cost ten times as much as commercial “artist paper,” it only adds a 2% to the price of a $1,000 sculpture. In a couple of decades, the difference between the two will be obvious. Second, as with any other market economy, the laws of supply and demand preside. How many of a particular object do you ever intend, or even want to fold? For our 50-hour American Alligator, the answer is simple: Two. Third, consider provenance. Certainly we charge more for any original pieces that have appeared in publications or exhibitions than we do for other examples. We also remind our students and colleagues that the origami art industry is still very young, and so prices will fluctuate wildly. The bottom line is that the agreed price must satisfy both parties, not only at the time of the transaction, but many years later.

Other Costs

When we fold models for commercial use, we sometimes fold pieces designed by others (with their permission, of course) especially when their design royalty fee is less than the cost for us to design an original alternative. We similarly authorize others to fold and sell origami works designed by us, and as a general rule, the written agreement typically includes a five percent design royalty to us. The design itself is worth something, and that should be part of your price. If you are selling through an art gallery, expect them to mark up your cost by 100 percent to cover their time, overhead (insurance, rent and promotional expenses), and so that becomes part of your price too. Do not forget taxes. Any of your income will be shared with the government, and so if you have your eye on something you want to purchase with the income from an art sale, be sure you are considering net (after taxes) income.

Intangible Rewards

Most purchasers of major works from our gallery are museums, and we are always delighted when a piece of our work is acquired for public appreciation. Our most recent show as of this writing was a display of origami flowers for the Honolulu Museum of Art at their Spalding House facility in Makiki Heights, a neighborhood of Honolulu, Hawai‘i. This display was Michael’s vision, and he designed each of the pieces (albeit with my hand in the Ohana Orchid plant and his Plumeria). Some museums keep the art for future events and shows. Some facilities, such as the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum in Tucson (and the Honolulu Museum of Art) do opt to sell some of their works by contemporary artists in order to raise funds to support upcoming artist-in-residencies.

Before our last trip to Honolulu, Michael and I were contacted by an accomplished hand papermaker, Allison Roscoe. She is the resident paper-maker at the Honolulu Museum of Art — Spalding House. Rather than build our exhibit in Massachusetts (and then worry about what might happen when it was shipped to Hawai‘i), we decided to travel there to make some of the paper there and fold it on site. At the museum, we had the pleasure of working with Allison and several other local artists. We also held folding workshops, and a hand paper making workshop, together with Allison, so that other budding origami artists could meet her and try their hand at making custom, high-strength, (and exceedingly thin) abaca paper. We back coated, trimmed, folded, and assembled the art for display, right in front of visitors. For ten days in January, when our friends back home were coping with a long and bitter New England winter, we were basking in the beauty, warmth and fragrance of Honolulu! Re-connecting with our old friends and relatives, making new friends, and working with an accomplished colleague such as Allison made our visit delightful. Such intangible considerations might also figure into the price of your art.

Alexander and LaFosse build their display of origami flowers for “Less = More,” Honolulu, 2015.