Origami Preservation

CREATE THE RIGHT CONDITIONS FOR LONGEVITY

BY ORIGAMIDO STUDIO COFOUNDER RICHARD L. ALEXANDER

Living plants make many different types of cellulose fibers. These versatile polymerized chains of simple sugars can be “assembled” by the plant’s cells to be as loose and airy as a cotton ball, or so durable and dense that we use it as hardwood flooring. It may be as moist, supple, flexible and young as a blade of newly formed grass, or it may be tightly compressed by centuries of growth above it, as in the rigid trunk of a giant sequoia tree. Because plant cellulose is of biological origin, paper exposed to the elements will eventually decay, as any dead plant would. The rate of decay depends upon many factors, including time, temperature, moisture, sunlight and the presence of biota (microbes such as yeast) capable of utilizing the cellulose as an energy source.

When we make paper, not only can we choose to start with different types of cellulose, we can also process it using a wide variety of techniques, and so the resulting papers can be strikingly different. If you want to preserve your folded art, it helps to know what type of cellulose was used, how the pulp was processed, and how the paper was made. Some paper-makers ferment the harvested plant materials first, to biologically digest the protoplasm. Most paper-makers use chemicals and heat to digest unwanted parts of the plant. Either method also softens the remaining cellulose fibers. We previously described the kraft process, when pulps are treated with strong chemicals, primarily to remove the lignin. Any residual acidic compounds may continue to attack the cellulose structure over long periods of time if the paper fiber matrix does not contain buffering salts to counteract this reaction.

Assuming that you have folded your work from acid-free, archival, art-quality fibers that have been colored with stable inorganic pigment, your origami sculptures probably need little care to protect them from the big four enemies of paper: excessive moisture, bright light, critters and fire.

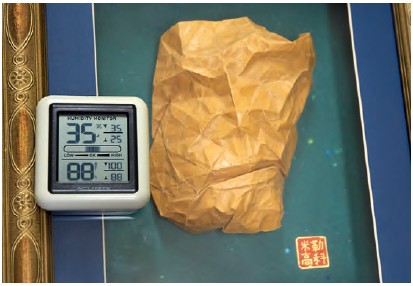

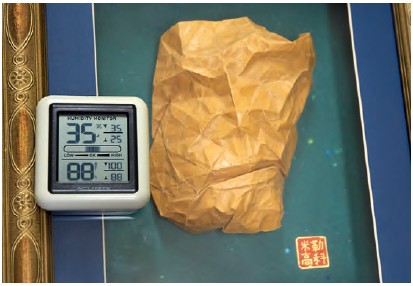

HUMIDITY: Most of the larger, professionally managed museums keep their paper works of art in an air-conditioned space set to 68 degrees Fahrenheit, and 50% relative humidity. Digital thermometers that also indicate the relative humidity are now readily available in large department stores. Some of them indicate the highest and lowest values (both for temperature and for relative humidity) during the previous day. This is helpful if you want to determine if you may have a problem in your intended storage area. When the humidity level is lower than 20% most papers become more brittle, which puts them at risk of cracking.

Your climate may require special storage precautions, perhaps only during certain seasons of the year. In general, rooms with regular water use (bathrooms, kitchens, basements, and laundry rooms) are not ideal for storing paper art. Attics experience large swings in temperature and humidity. The best place to store your art when it is not on display is usually in a linen closet or clothing chest. However, cedar wood with aromatic natural oils is used for clothing storage chests because those oils infuse the contents with a fresh fragrance. This fragrance also discourages some insects, but most organic volatile compounds (that our noses detect as fragrance) are also reactive chemicals that can promote unwanted chemical changes the paper. Acid-free photo storage boxes and “museum boxes” are considered best for storing your origami art. If your storage area has any chance of wide swings in humidity, we suggest wrapping the object in archival tissue, and then sealing it in a zipper-type freezer bag. This also allows you to trap air that might provide some cushioning if the container is accidentally dropped. The jury is out on using plastic storage containers for storing origami. Some plastics will turn yellow or become brittle, others may emit plasticizer compounds, such as phthalate oils. We never use metal containers because they can oxidize (rust), and we don’t use wooden boxes because of cost and weight. In the presence of moisture, wood can promote mold growth. If the wood has not been kiln dried, lignin might migrate onto the artwork, causing a stain.

“Portrait of a Friend” and other framed pieces are kept in a room with low humidity.

Faded origami lobster shown against a fresh piece of the same Leathack paper. Marbled paper laminate, back coated with starch paste, shows “foxing.”

Proper care: “Wilbur the Piglet,” wrapped in archival tissue, with data label in a labeled archival cardboard box.

BRIGHT LIGHT: Direct sunlight consists of radiation that reacts with, and changes the chemistry of many inexpensive organic dye molecules. Some but not all of the most stable pigments are highly toxic (such as lead and cadmium salts), and so artists compromise to select less toxic, but less permanent, alternatives for bright reds, yellows and greens. Today, unless the pigments are white and brown, it is safe to assume that even the most colorfast pigment systems might contain ingredients subject to at least some fading during prolonged exposure to bright light. The most colorfast pigments are actually ground bits of rock found on the earth’s surface. They are chemically stabile precisely because they have been exposed to the elements of sun, wind and rain for thousands (perhaps millions) of years. The pigment system that artists have developed through the centuries (and that we still use today) mostly takes advantage of stable, ground minerals and chemical oxides (such as brown iron oxides and white titanium oxides); if your folded work is pigmented, there is little need to worry about sunlight.

CRITTERS: Art appraisal TV shows have been popular for decades, and the value of a piece of art is largely based upon the quality and condition of the object. Etchings and prints that have been passed through generations often appear on these shows, and are sometimes appraised for a fraction of their potential value because of “foxing.” This is a general term referring to discoloration of paper, which can be caused by microbial growth. Storage must exclude insects and mice for obvious reasons, but don’t forget the critters too small to see.

MOISTURE: Foxing often indicates that excessive moisture was present at some time. Tree bark contains iron from wind-blown dirt, as well as iron that entered with water through capillary action. Any iron present in the cellulose can oxidize (rust) in the paper. Moisture can also allow fungal growth, and the products of microbial metabolism can produce a visual change, if not a dramatic physical degradation of the strength of the paper. But don’t be so overly concerned about this that you soak everything in poison!

FIRE: Paper burns! Keep your precious collection away from stoves, furnaces, electrical equipment and the like.

Fires, critters and floods have robbed us of the historical artifacts of origami art simply because so few pieces have survived more than fifty years. Hopefully, better knowledge about origami art storage will help to preserve what we have for future generations.

In summary, protect your art by using a sturdy archival box designed to store photos or artwork. Store the boxes in a closet within the living space of your home. Add a note with all of the pertinent information about the model: designer, material, size, dates, source of the instructions, etc.; this information will tend to escape your memory.