Chapter 7 Cultivate a Professional Reputation

Indulge us as Generation Xers for a moment over a late twentieth century TV drama, er. While the show had many memorable moments, including a new surgeon’s parking lot fist pump after receiving praise from a supervisor (something that should resonate with graduate students), there was a line repeated at numerous points over the series that influenced both of our careers: “You set the tone.”

In chapter 1, we introduced the need to strategically develop career competencies. Among these was the nebulous category of professionalism, which includes things such as the establishment of a professional image and time and project management. At this stage in your life, it is probably no surprise that how other people perceive you matters, and the need for time and project management skills makes itself quickly apparent to PhD students. Unfortunately, mentorship in these areas can vary, and the structure of PhD programs does not help. Once one gets past the coursework stage, it is possible—in fact, often far too probable—for PhD students to become socially isolated, reducing their opportunities to carve out a professional niche. Moreover, preparing for comps and writing the dissertation are activities that lack a clear end point: One can always do more research, read more literature, tighten one’s text. And time can seem plentiful, particularly if one is willing to work long hours in the evenings, on weekends, and on holidays. When you combine these factors and consider the infamous Parkinson’s law, which asserts that work expands to fill the time available, it is a recipe for potential disaster. In the PhD program, work will continually expand, just like the universe itself, complete with black holes in both cases.

Fortunately, all that flexibility means you have tremendous personal agency to identify both how you would like people to describe you and how you would like your daily life to function, and then to adopt strategies for achieving these outcomes. In this chapter, we introduce a set of practices to increase your efficiency and reinforce a personal brand that is associated with competence, conscientiousness, and general professional awesomeness. In addition to advancing your longer-term career goals, these practices can make your life better immediately. We will warn you, though, that many are outside what you typically observe in academic life, and you may feel resistant at first. Academia often cultivates an image of difference and separation from the rest of the professional world as well as a strong sense of individuality, so you may be tempted to believe that you have unique working habits and a style that only you really understand. While some things we suggest may not work exactly for you, we urge you not to play the “this doesn’t apply to me” card over and over. As a scholar, you are naturally interested in evidence, so treat yourself as an experiment with a sample size of one. If, after a few months of reduced stress, met deadlines, and professors starting to treat you like a peer rather than a student, you truly feel the ideas are not for you, you can always stop.

How can I cultivate a professional reputation?

People described as being professional share a number of qualities. They are typically known for being reliable, conscientious, and attentive to detail. They understand the need for appropriateness relative to their circumstances and the importance of acting graciously. At its core, professionalism is largely about treating others respectfully in a broad sense. When you make the effort to be punctual and to ensure that your work meets a particular standard and that your behaviour is appropriate to the situation, you are showing respect for other people’s time, energy, feelings, boundaries, and so forth.

You personally set the tone for being professional; it is entirely in your own hands. Cultivating a professional reputation requires taking small actions regularly to consistently demonstrate respect for others. What is often unappreciated is that failing to do so leaves other people with a sense that you disrespect them. This disrespect is almost always unintentional. But make no mistake: actions such as arriving at class a few minutes late, being unprepared for a meeting or interview, and failing to thank someone who has made an effort on your behalf are not just perceived as disorganization; they can be and often are perceived as a lack of respect for another person’s time and energy. And over time, a reputation for being disrespectful can be deadly to your career.

Adopting three mindsets will help you avoid unintentional disrespect:

1. Graciousness is not optional: A lack of attention to gratitude will seal your reputational coffin if you are not careful. Always, always say please. (We feel we shouldn’t have to write that, but sadly a shocking number of people at all career stages skip this basic human courtesy.) And, closing the loop, thank people when they do something for you, even if it is small, and even if they are your supervisor, instructor, or committee member. When people do things for you—share an idea or source, provide you with feedback—they are giving you a gift of their time and attention. As your parents undoubtedly taught you, failing to say thank you for gifts is unspeakably rude. People typically notice when they are not acknowledged for their efforts, and you can easily turn a potential champion into someone who has no investment in your success. If someone is helpful to or supportive of you, take the minute it takes to express your gratitude. If someone provides you with detailed feedback on your work, provide a more lengthy positive response (even if you don’t agree with their comments). If you intend to say thank you but fail to actually do so, the person is left with the impression that their efforts are not valued by you or that you feel entitled, and that person will be unlikely to help you again in the future. (If someone needs to ask if you received the email of detailed comments on your chapter, you are almost certainly added to their “people who don’t impress me” list.) Make it a habit to thank people within 48 hours, for all things large and small. Better that you have the reputation of being too polite and thoughtful than of being a jerk.

2. Your department is your workplace, and the people in it are your colleagues: After years in the educational system, it is easy to treat your doctoral experience as “more school.” But to cultivate a professional reputation, you must show awareness that this is your professional training ground. While it is tempting to become casual and overly familiar with respect to language, clothing, hygiene, and social behaviour, it is not appropriate to the circumstances. Professionalism requires a strong sense of context, as well as respect for differences in power and authority. Here are some things to avoid: being late; showing up at meetings unprepared, without pen and paper or tablet/laptop and a clear purpose; profanity; discussions of illegal or illicit activities; sloppiness, be it in personal attire, non-proofread emails and materials, or data and file management; anything beyond light alcohol consumption. Save these behaviours for your private life (or avoid them entirely).

3. All information is private unless you are told otherwise: The move from casual student environments into the professional world can be difficult for PhD students, as information can be sensitive in multiple unforeseen ways. Conversations “just between us” are not always so, emails are forwarded, and information that seems benign may prove explosive. You need to become highly sensitive to showing others respect by developing a hyper-instinct for discretion. As a teaching assistant, you are privy to confidential student information; as a researcher, you may have access to data sets, draft papers, and similar things that are not meant to be shared. Sometimes it’s crystal clear; other times not. Always err on the side of caution, asking if something can be shared (and even more importantly, explaining why it needs to be). And if you are gossiping or voicing opinions about faculty, other graduate students, undergraduate students, staff, or anyone else, know that it will get back to them or be repeated to someone else. If you wouldn’t say it to their face or send it to them in an email, rethink voicing it at all.

How do I create a professional image at conferences?

Conferences can be critical for building impressions, good and otherwise. This involves your work and accomplishments, skills and competencies, general professionalism, and personality—roughly in that order. Conferences provide snapshots of you, and it’s important to make sure the snapshots are accurate. Keep in mind that you are always “on,” at least to some degree, and make the most of it. Anticipate certain questions and be prepared to summarize your dissertation, describe your research interests, lay out your professional roadmap, and, of course, highlight your key competencies.

It is important to figure out the correct norms for conference presentations and sessions. Professional-style conferences are typically more genteel and the questions are more affirmatory than critical. This is not the time to take apart the speaker’s entire framework of ideas, and it’s even okay to slip in self-promoting references to your own work. In contrast, it is generally considered polite at academic conferences to challenge the presenter’s work; people expect to be grilled about their basic ideas and assumptions and even express disappointment that “I didn’t get any good comments.” Take advantage of this, but use it carefully. Make it about the presenter’s work, not your own; the “statement pretending to be a question” is common but easily overused. Aim instead to ask questions that are constructive, that draw linkages to other work (not just your own), and that will promote interesting discussion in the room. You might be tempted to demonstrate your intelligence by aggressively pointing out the flaws in the presenter’s work. While there is latitude for this even as a PhD student, there’s also great risk of unintentionally creating an impression of being obnoxious. People may or may not have thick skins, but they always have long memories of times when they were publicly embarrassed. Given the smallness and interconnectedness of the academic world, there is no reason to make enemies, be it with an established professor or a fellow graduate student.

It is common at conferences to focus on Great Persons and try to interact with them. Fine, but a better investment than a one-minute forgettable conversation with an Eminence is time spent with ordinary mortals closer to your own world, including your own PhD peers. You might stumble into a serendipitous opportunity by talking to just the right person at the right time, but long-term connections are the big objective here. This can include having fun socializing, but being known as the party animal is not a good career move, whereas “one drink and then leaving” is not a bad reputation to have. And be attuned to the norms of conference dress codes, though this will vary. At professional conferences, dress like a professional unless you really want to stick out as the wooly-headed scholar. But academic conferences, especially in Canada, tend to be much more casual with a wide range from suits and skirts to hoodies and shorts. Our advice: Figure out the general norm and dress one level up.

How can I be productive?

Professionalism means doing what you say you will do and by when you say you will do it. You cement your professional reputation by getting things done—and done well, on or ahead of schedule. This requires the ability to manage time, resources, and energy to make this happen, over and over. By carefully managing your time and your projects, you will be more thorough, meet deadlines, and avoid accidentally missing steps.

Most productivity and time management tips are written for business audiences. The target reader works at a desk managing projects with clear, looming deadlines and has a boss who is highly interested in the worker delivering something (reports, analyses, new code, corporate strategies, etc.) by a specific date. No deliverable, no profit, and soon no job for the employee. These books tend to assume that the reader needs more time—sweet, uninterrupted blocks of time—to work on something with clear parameters and built-in boundaries.

PhD students face a very different challenge. While taking classes, you have various paper deadlines to balance and possible teaching or research assistant responsibilities. After classes are done, you are trying to coordinate reading literature with dissertation-related writing, more teaching or research work, a panel that you are organizing, and so on. But these responsibilities are typically done within a context of large amounts of unstructured time. The illusion of abundant time can be overwhelming, and the projects themselves get more challenging. Scholarly life is full of theoretical and empirical rabbit holes and blind alleys that can drain your time and energy. Again, dissertations in the social sciences and humanities lean toward the model of “go away and think,” and students are provided with limited direct guidance and supervision. Not only is this a route to inefficiency and years of drift, it also undermines the building of professional habits and demeanour.

Deliberately building project management skills increases your prospects for career success. And like other aspects of professionalism, it requires careful attention. Fulfilling your project commitments, and doing so in a way that allows you to retain some degree of quality of life, won’t necessarily happen naturally. Four basic steps that you tailor to your personal energy patterns and circumstances can ensure that you are achieving your goals while maintaining quality of life.

Step 1: Make a list of what needs to be done

Quite often, people try to just keep everything straight in their heads. The problem is that it is easy to forget things or to remember them inaccurately. The solution is simple: To determine what needs to be done, you need to get organized by writing a list of everything you have committed to and the associated deadlines.

“Wait,” you might be saying, “this is rather obvious.” Of course it is. But just like “eat right and exercise” is obvious but frequently ignored advice for healthy living, the practice of listing commitments and deadlines remains a habit that many PhD students have yet to adopt. If you have already done so, good for you: You have our full permission to enjoy a well-deserved sense of self-satisfaction. For our more mortal readers, let’s get down to business. Start with a large “brain dump” of commitments for a specific time period. (The academic semester is a good place to start.) Are you taking classes? If so, check each class syllabus and then list all of the readings, papers, exams, lab projects, presentations, and other class tasks, noting the associated dates. Are you working as a teaching assistant? Again, check the class syllabus and list all of the class tutorials, exam dates, paper dates, and other TA-related responsibilities and their dates. Are you working as a research assistant? Working on a conference paper? Do you have committee responsibilities? Other responsibilities that we have failed to mention? Do your best to think of everything you have to do over a specified time period, and then scan both your calendar and your email to see if there is anything you have missed. The more complete your list, the better. List complete? Excellent. Now just reorganize the list by due date and you have a clear picture of what needs to be done.

What do I do if I have taken on too much?

Feeling overwhelmed is awful. The panic in your chest, the feeling that you are going to let people down, that you will need to do nothing but work and more work for weeks or months, the associated anxiety and insomnia … It is the worst. And the fears that are associated with it are often well based: If you are someone who fails to meet commitments, who is constantly behind on timelines and long on excuses, it reflects poorly on your professionalism. At a certain point people may start to perceive you as either unreliable, incompetent, or both.

If the amount you have on your plate is not realistic relative to the time available, you need to identify where you can make changes. Are there any committed times that could be reduced? Is working fewer hours in your part-time job, or getting help with family responsibilities, or reducing commute times an option? (You may be tempted to cut back on sleep, fitness, or personal hygiene. Please don’t.) Chances are good that your ability to make change in the committed time part of the equation is quite low. So then you must ask, are there any projects on your list that you don’t really need to do at this point in time? Or are there some steps within the projects that can be removed or streamlined?

Ideally, you can solve your overload problem well in advance: You can tell people that you will need to decline a particular opportunity for now, or that you will need to have someone work with you to complete it, or that you will do it for a later deadline. These conversations can require a certain degree of bravery, but it is better to be upfront with people as early as possible rather than disappoint or anger them at a later stage. On the plus side, the discomfort of disentangling yourself from overcommitment may serve you well in the long run as you instinctively avoid taking on too much in the future.

As we have said at several points in this book, be attuned to your mental health and wellness. Seek balance and support networks; check in regularly with a counsellor or other source of assistance. Everyone feels stressed and overwhelmed sometimes; learn to ask for help in identifying when it is too much, and seek the support you need.

Step 2: Break activities down into smaller tasks, distinguishing between high- and low-energy tasks

Start with the list that you created in step 1. Now look carefully to see how you can break the items down into discrete tasks. For example, the paper due on October 31 requires numerous individual steps to complete it: creating an outline, searching the library database for relevant sources, reading these sources, writing a first draft, editing the draft, writing a second draft, completing the bibliography, and so forth. This detailed list allows you to create target completion dates to keep you on track and, importantly, to manage your time and energy strategically.

When you look at the more detailed list, it should be apparent that some tasks (such as writing, reading, or data analysis) must be done when you are at your peak, and other tasks (such as editing a bibliography) can be done when your energy levels are lower. By clearly labelling tasks as high or low energy, you can strategically assign the high-energy tasks to those time periods during which you are usually highly productive, creative, and energetic, and assign the low-energy tasks to the times when you are usually a bit spent out. (At this point in your life, you probably have a good idea of which times are which for you; if you are not sure, just pay attention to your energy levels for a few days.) Your goal is to protect your high-energy periods for high-energy work, and restrict all low-energy work and other activities (like dental appointments and coffee meetings) to low-energy times; to do this, you need to clearly label the tasks.

Table 7.1 Worksheet: Tasks, target completion dates, and energy designation

Task |

Target Completion Date |

Energy Designation |

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

Step 3: Block work time into your calendar

The trick to getting things done (and done well and on time) is to schedule the work times into your calendar and to respect these times. Remember, an unstructured schedule and its illusion of endless time is your enemy; imposing structure on your days is necessary. Doing so is simple:

1. Block off all committed times (classes, work hours, commute times, sleep, fitness, family responsibilities, etc.) in your calendar.

2. For each task and project, estimate the number of hours you will need. Because most things take longer than you assume, and to provide cushion in case of unanticipated events (illness, transit strikes, broken water heaters, etc.), increase this number by 50 per cent.

3. Working back from the deadline, schedule task-specific working time in your calendar, assigning high-energy tasks to the high-energy time slots.

Now, in doing this process, you may be prone to optimism (“I don’t need to increase the project hours. My original estimates are realistic.”). We understand. But imagine—just as a thought exercise—that we are right that things tend to take longer than anticipated and that life sometimes throws curveballs. Blocking the extra time into your calendar allows you to quickly identify if you have taken on too much and then make needed adjustments. Of course, if your original estimates are accurate, there is risk of turning down opportunities that you could have completed. For this reason, we suggest that you treat the thought exercise as just that. But if your gut is telling you that you might have taken on too much, respect that and proceed cautiously.

Be strategic in how you enter things into your calendar. It is imperative that you save your high-quality times for high-quality tasks. The most important thing to schedule is your writing time. Social science and humanities doctoral programs involve a lot of writing: Most courses involve written assignments, and after courses are done there is (in most traditional programs) the dissertation proposal, the dissertation itself, and other writing that you seek to complete. Writing should therefore be paramount in your schedule, and we strongly suggest regularly scheduled short writing sessions (e.g., every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from 9 to 11 a.m., or every Monday to Friday from 1 to 2 p.m.). This approach, admittedly, goes against the typical academic binge-writing style, in which the author procrastinates and then completes all the writing tasks within a large block of time, like a second-year student cramming for a final exam. To be sure, there can be a time for binge writing. But like binge eating and binge television watching, it has both short-term satisfactions and long-term consequences, and inevitably the former exceed the latter. Regularly scheduled writing may not fully eliminate the need for occasional binge writing, but it can reduce it (and the associated stress) dramatically.

To make the best use of high-energy time, you need to consciously batch together low-quality tasks (e.g., getting books from library, checking citations and bibliographies) and commit to addressing them only during low-energy periods in the day. Email in particular can suck up time and energy with little payoff. Make a decision to file email into a batch folder that you will address at a prescheduled low-energy time; during your high-quality work times respond only to email that, if not addressed immediately, may result in someone bursting into flames.

How can I take advantage of unexpected time?

Most weeks include a fair bit of relatively useless time. Sometimes this time is structured into your schedule (commuting time or time sitting on the pool deck while your child takes a swim class) and at other points it is unanticipated (time waiting outside your supervisor’s office because his department meeting is running long). Sometimes it can be good to just stop, take a breath, and relax looking at online cat videos (so cute!). But sometimes it is nice to make use of this time, and you can plan ahead for these opportunities by ensuring your writing projects are accessible through the mobile device you are undoubtedly carrying. The three-minute note here and the five-minute idea there will actually add up to paragraphs, and the perennially growing file creates within you a sense that the project is moving, while eliminating the frustrating “start up” time that can occur if you don’t work on a project regularly. If you adopt this practice, you will start to see small windows of time as bonus time. A friend is late to meet you for coffee? Great, you can edit your introduction! Your child has a 30-minute gymnastics class that you sit through every Monday night? Awesome, you can aim to write 150 words each time. This approach needs to be tempered; you should never feel that every second must be used efficiently. But if you can tackle some tasks during found time, you can free up more time for other things in the future. Which, we must stress, could include a run by the river, or beer with a friend.

Step 4: Work your calendar

Ah, plans. Like fitness schedules and New Year’s resolutions, making them is the easy part. But the execution, well, that takes discipline. And this is where the difference between the professionals and the others shows itself.

Scheduled writing is often the most challenging commitment to keep—which is ironic, since this single activity is most associated with a PhD student’s success (or lack thereof). Honouring your scheduled writing commitment as much as you would honour a class, meeting, or other work obligation is the sign of a true professional. But it can be hard: While thinking about writing is exhilarating, and reflecting on completed writing is satisfying, the in-between period—you know, the actual writing—invokes a broad array of emotions, not all of which are pleasant. As well, the more theoretical and interpretive your work is, the more likely it is that writing is the primary or even sole activity itself, as opposed to gathering and analyzing empirical, documentary, or archival data and then writing about it, making writing even more paralyzing.

Many writing problems occur because people are trying to plan, write, and edit simultaneously. To get around this, start with a clear outline and then focus your daily efforts on small units within the outline. Allow yourself to put ideas in point form, making notes to yourself in the draft to be dealt with at a later time (e.g., “insert three to four sentences about Jones et al. here,” “add citations”). Avoid the temptation to edit as you go along so that your creative thoughts, which will generate the innovative ideas that matter to your work and your discipline, are not impaired by your more critical editorial thoughts. Aim to get a full first draft completed before you turn to editing the work. The more you focus on small sections and just getting ideas down, the more your writing time can actually be allocated to … writing.

Working your writing time—treating it like the heart of your job—is key to your professional success. It can be tempting to schedule something else in the writing time slot “just this once,” or to fail to use the time wisely when you are in it. And it can be tempting to use low-quality tasks as “short” breaks during your productive periods (“this paragraph isn’t really going anywhere … I’ll work on my passport renewal form”). Remember that tasks expand to fill the time available, and the task might end up killing your productivity for the day. The small writing time investments add up to significant results. And the more frequently one does something, the easier it becomes, as both the runner and the smoker can attest. Use the power of habit and routine to your advantage. To further your progress, consider establishing a writing group that provides support and creates a sense of accountability.

Our experience: Loleen

One thing that can be helpful in meeting writing goals is an accountability system. Within my first year of returning to academic life, I set up a writing accountability group with six other female tenure-track professors. We came from a variety of academic disciplines but shared a similar tenure timeline. The group met monthly for two years and was fundamental to my progress. Knowing that these peers were aware of my month’s goals helped motivate me to push forward on my writing when other things seemed more pressing.

Making it a practice to repeat these four steps will develop your professional image. You will get projects done on time, giving others the sense that you are on top of things and take your work seriously. People will notice that you are organized and competent, and they will respect you for this. Plus, you will have time to join them for a squash game or coffee.

How do I communicate professionally?

Many people believe themselves to be great communicators because they find it easy to articulate and express their thoughts. But this only counts if people are receiving and absorbing the information as intended. Communication is not about you—it’s about the people to whom you are communicating. It incorporates courtesy, discretion, and respect for others’ time. It also requires understanding that not everyone views the world like you do or thinks and processes information the same way. Your quick efficient message may be seen as terse and rude; your effort to explain all of the facts may come across as an eye-glazing monologue. The failure to appreciate how others might reasonably process what one is saying is the cause of many misunderstandings and tensions (“Oh, no! Here comes Dr. Longwinded”) and undermines many otherwise professional people.

Our experience: Jonathan

A practice I have always tried in my professional career is to listen and communicate with people on their own terms, in ways that resonate and make sense to them and how they process information. Early in my career I knew an academic administrator who was very well liked, and people often raved about how easy it was to talk to that person. I also respected the person, yet our occasional conversations were awkward and stilted. Eventually I realized that we had the same technique of letting the other person set the pace of the conversation, and were waiting for each other to take the lead.

Professional communication encompasses the principles that we have talked about already—respect, discretion, sense of appropriateness—while effectively sharing information. What many people don’t recognize is that communication is about the other person. If the other person misinterprets or misunderstands the information you are attempting to convey to them, you need to figure out how to alter your communication style to meet their (and ultimately your) needs.

Table 7.2 Professional communication

DO |

DON’T |

|---|---|

✓ Include a proper salutation (“Dear”) and valediction (“Sincerely,” “All the best,” etc.) in all email and written communications. |

✗ Address a stranger or person with higher professional status than you (e.g., professor, potential employer) by their first name until you have clearly been signalled to do so. |

Many universities have resources and services—housed in libraries, teaching centres, research offices, and graduate faculties—available to help graduate students develop their skills in packaging and presenting ideas. It is also helpful to simply watch other people’s communication styles carefully and to consider what you find effective. Give careful thought to the professional tone you want to set, and seek out real-life examples of people to emulate.

How can I network effectively?

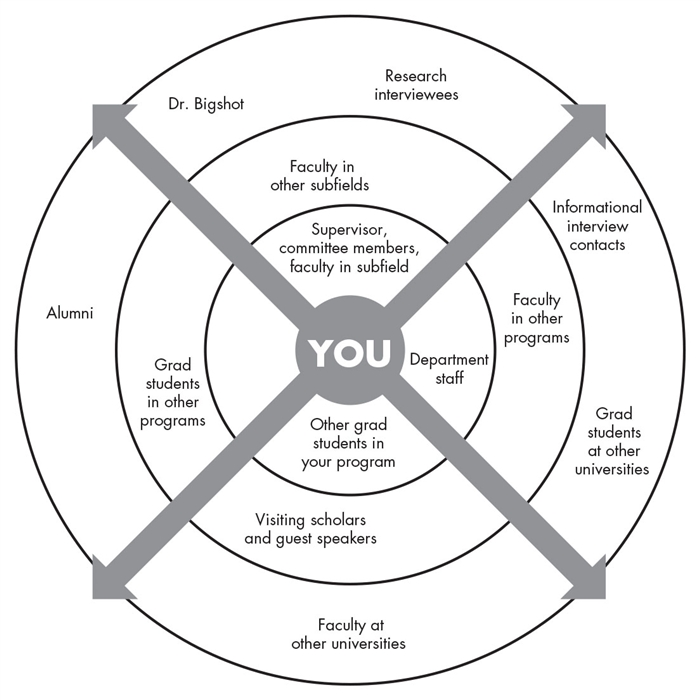

A great deal of opportunity and influence comes about because someone knows someone else, or someone knows someone who knows someone, and so on. The academic world itself is densely interconnected, and academics are often good at networking with other academics. But as we suggested that your goal be a successful, rewarding career that uses your talents and the skills you developed throughout your education, we encourage you to expand your networking beyond academic circles. While interacting with individuals beyond academia can require a bit more effort, it is in your interest to do so since, as we note in the next chapter, many career opportunities are not advertised. As you build your networks, you increase the number of people who are in a position to suggest your name when one of their contacts mentions they are looking to hire someone—the “weak ties” we talked about in chapter 4 that can be vital to employment networks. Think of your professional network as a sphere of concentric circles, and constantly be aiming to push out further (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1: Expanding your professional network

Networking takes many forms. It often has a strong social component; thus, many professional events and receptions are explicitly labelled “Networking Opportunity,” in case anyone wasn’t clear. But it also includes one-on-one meetings (such as the informational interviews that we discussed in chapter 4), email contact, connections through social media, and any other way you bring your professional abilities to another’s attention and vice versa. Some people over-network—they treat every encounter as a transaction, flood others with updates (“just wanted to mention my book review got published and here’s a copy”), and give the feeling that every contact is just a stepping stone to a more important one. But the more common problem is under-networking. PhD students can be particularly prone to this because they are typically more introverted than the general population, and academic culture emphasizes modesty and understatement. Many PhD students get the message to let their work do the talking, and thus do not cultivate the professional skills of connecting and building networks, to their own detriment. Networking can appear superficial, because some of it is. But, for better or worse, it is how people get to know each other and decide if there is professional value to the relationship.

Networking also requires effort. This may mean going to things you don’t really enjoy and striking up conversations with people you don’t know, or spending time calibrating an email to ensure it says exactly what you want it to say. It also means thinking and planning ahead. Are there specific people you want to talk to at an event? Are you targeting the right person with your message? What do you want them to learn about you? What information would you like to learn from them? In some cases it may require writing down and memorizing talking points beforehand to ensure you get a crucial message to a crucial person right. Take pride in being prepared.

As a PhD student working your career, you hopefully have a number of professional attributes and angles to fuel your networking, but the big one will be your dissertation, which (hopefully) showcases your main interests and abilities. So it’s important to be able to talk about it in ways that make sense, both inside and outside academic circles. Take advantage of competitions that require you to summarize your dissertation in a few minutes, and develop further mini-versions with hooks that pique people’s interest, making them ask for more (“You’ve uncovered the theory of the universe? Please continue.”) Similarly, you should develop equivalent summaries of your skills and competencies. Be able to speak convincingly and confidently about what you can do and why it is relevant and valuable. You set the tone. You’re a professional.

How can I use social media effectively?

Professionalism is timeless, but its tools change, particularly the use of technology. Navigating this change can be a challenge, especially as conventions evolve around the boundaries between the professional and personal. A person dropped into our present-day world from the twentieth century would be shocked to learn that seemingly professional people would freely post random personal thoughts that could be viewed (and archived) instantly by anyone in the world. The twenty-first century person, on the other hand, may be surprised to learn that it was once common for faculty members to list their home phone numbers on course outlines, often with a gentle reminder to not call after 10 p.m. Boundaries and expectations change, and not always in one direction. There is a general evolution in society toward more openness about personal lives, which is often a good thing, but there are always limits.

The online world gives you ever more tools to express yourself both personally and professionally, and you need to decide how those two relate. We urge you first to keep at least some boundaries and privacy controls between your truly personal life and everything else, so that no potential employer will ever see an image of you in a bathing suit. Beyond that, you have agency to decide how much you want your professional online brand to be animated by your personal style, and which online platforms provide the best opportunities to do so. The one important thing is consistency. The online brand you show to the world (different than what you show family and friends) should give people confidence in your abilities and your judgment, rather than making them wonder about your professionalism.

Using social media and similar online tools is a professional skill in its own right, though many people overestimate their talent here. Simply posting lots of content that people respond to is not necessarily a sign of anything; it can even be detrimental if it’s not backed up by other online or offline accomplishments that demonstrate you do more than live on your phone all day. If social media skills are something you want to demonstrate as a skill set, you need to show clear planning and evidence of your effectiveness.

I am at the end of my program and didn’t do any of this. Where do I start?

This is our closest thing to a life skills chapter, as professionalism is a lifelong quality and there is no reason why you can’t start becoming more professional today. We said above that academia can be a terrible place to develop professional skills, especially for productivity, and we are utterly confident that many of your peers are struggling with these issues as well. It may take time to unlearn bad habits of productivity and develop good ones, but you can become steadily better at interacting with people and developing confidence. Nobody was born a professional. They developed into professionals, and so can you.

And, of course, it is never too late to go back through your publicly accessible social media feeds and remove anything that may be viewed as unprofessional.

These ideas are interesting, but how do I actually make them work?

Professional reputations are built one interaction at a time: If you are selectively or sporadically professional, you will not be setting an overall tone. Knowledge of your occasional lack of professionalism—missed deadlines, poor communication—will eventually start to creep into your professional reputation. This means that professional behaviour, including time and project management practices, must become a habit to be effective.

We have been advising that you continue to ask yourself the question, Given both my future goals and the information currently available to me, what is my best decision right now? As we said at the start, professionalism is about setting an overall tone, and it is in your interest to start setting that tone immediately. No one is perfect, and professionals are inevitably stronger in some of the above things than others. But it is the overall tone—that sense of reliability, conscientiousness, respect for others, and graciousness—that pulls things together. There will always be loose threads, weak points, and sometimes a paralyzing embarrassment as you suddenly forget someone’s name at the worst possible moment, but if you focus on setting the tone, it will keep propelling you forward.