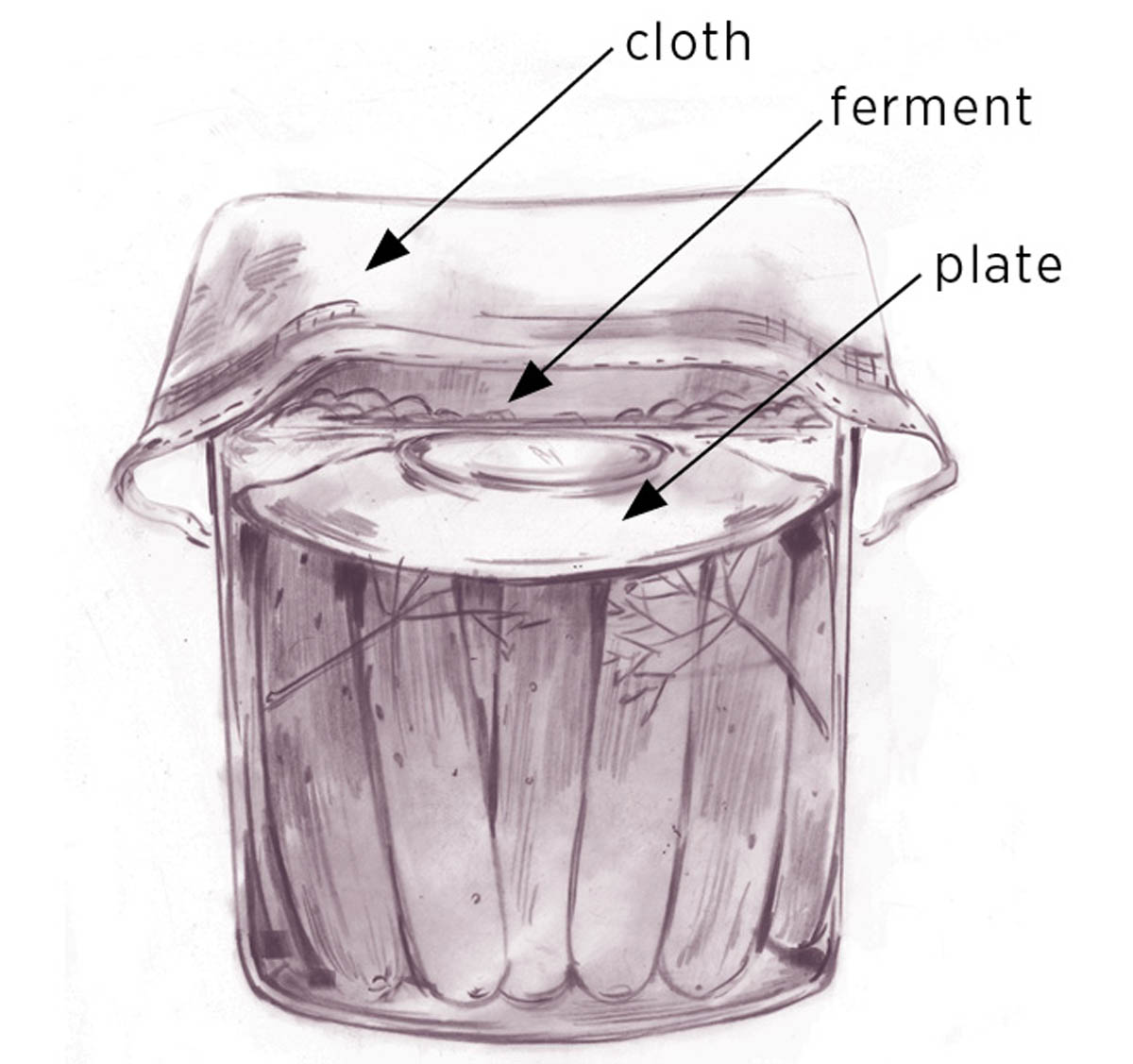

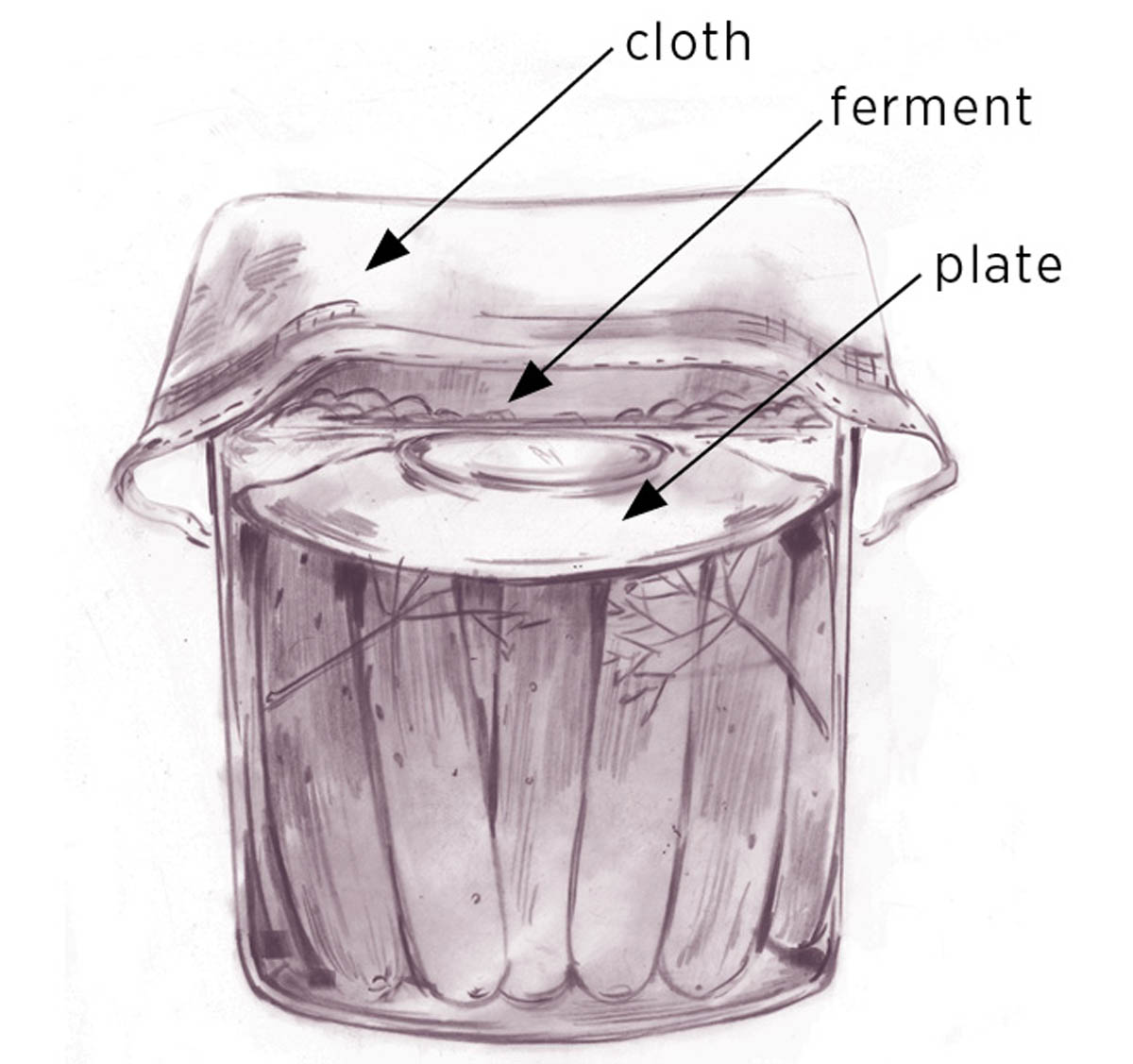

Fermentation setup

Some of our most delicious foods are fermented. Beer, wine, cheese, and good bread are all the tasty results of a good ferment. Who knew controlled rot could be so delectable? Not only are they palate pleasers, but fermented foods are also loaded with probiotics, the beneficial bacteria that populate a healthy gut. Our modern diet doesn’t include as many fermented foods as it once did, and even foods that are fermented are often pasteurized, a process that destroys the active probiotics. But you can have these good bugs back in your diet. Just make fermented foods yourself. Here are some of the most popular questions I’ve been asked about fermenting.

Q: Fermentation seems so mysterious. How does it work?

A: Fermenting is one of the oldest forms of food preservation and is really simple to do. It’s a process that happens naturally — one that you can accomplish with no special training or specialized equipment. Here’s how it works.

Essentially, you are just encouraging the natural lactic acid bacteria found on all produce to proliferate. As they do, they create the lactic acid that flavors and lowers the pH of your recipe to an acidic level that protects your food during storage. Salt — either sprinkled on chopped or shredded produce or mixed with water to form a brine — is frequently added to abate any contaminating bacteria, molds, or fungi.

Between the lactic acid that is generated and the salt that is added to the mixture, the ferment is very inhospitable to pathogens, making fermentation a safe and delicious way to preserve food. Try the recipe for sauerkraut and you will see just how easy the process can be.

Q: What is lactic acid? Do I need to add it to the crock?

A: Lactic acid is created by the fermentation process. Unlike acetic acid, also known as vinegar, you do not need to add it to the crock. It results naturally as the beneficial lactic acid bacteria that are ever- present on produce digest the sugars in the fruits and vegetables and generate the lactic acid.

Q: Why didn’t my pickles ferment?

A: There are a few factors that can keep a ferment from taking off. Here are two of the most common:

Too cold. Cool temperatures will slow, or even prevent, fermentation. You can use this to your benefit by placing your crock in a cool basement in the summer months to slow down the fermenting action. But the room temperature shouldn’t be so cold that you would call it chilly — it should be a comfortable to cool room temperature for ideal fermentation.

Too strong. If you add too much salt to your pickle brine, you can halt fermentation. Some salt controls bacteria, but too much will halt the active bacteria that keep the ferment moving along. You should use a little less than 1 tablespoon of kosher salt per 1 cup of water, or about 3 tablespoons for every quart.

Q: My fermented pickles have a thick white layer on the bottom of the jar. Is that okay?

A: A thickish white layer on the bottom of the jar is most likely made up of dead yeast that has settled in the bottom of the jar. You will notice this at the bottom of kombucha (fermented tea) and other fermented products as well. It is not harmful and is a natural by-product of the fermentation process.

A white film on top of your ferment should be removed. This is a layer of yeasts and molds that are trying to set up house in your crock and, while not harmful if removed, can upset the balance of your ferment if left to proliferate into a thick pad. Check your fermentation crock regularly and gently dip off this “bloom” as it develops. Be sure to replace any liquid lost in its removal by topping up your jar with enough brine to cover your produce (just under 1 tablespoon of kosher salt dissolved in 1 cup of water).

Q: Some of my produce is poking out of the top of the ferment. Is that okay?

A: It’s very important that all of the produce that you wish to ferment is submerged under the brine. Food that is exposed to air, and airborne pathogens, is likely to rot rather than pickle. Use a clean plate just smaller than the opening of your container to weight your produce down and keep it well covered with liquid.

Fermentation setup

Q: My ferment is evaporating. What can I do?

A: It is not uncommon for some of the brine to evaporate during fermentation. But it is important that your food stay submerged. If you notice your brine is getting low, you can top it up with a solution of just under 1 tablespoon of kosher salt dissolved in 1 cup of water.

Q: My ferment is bubbling. Has it gone bad?

A: Bubbles occur naturally in the fermentation process and are a good sign that things are going well. As the sugars are converted into lactic acid and acetic acid, carbon dioxide is created and sometimes appears as bubbles in the crock. As the process nears its end and your kraut or pickles are finishing their fermentation, the bubbling action will slow.

Q: There is mold on top of my ferment. Is it rotten?

A: It is not uncommon for a cap of mold, or bloom, to form on the top of your ferment. This is particularly common in the beginning stages of fermentation, when the process hasn’t yet had time to create enough lactic acid to lower the pH of the brine.

If you notice a patch of mold or bloom floating on top of your crock, just gently scoop it off. Wash the plate or container you are using to weight down your produce. Top off your brine if necessary by dissolving a little less than 1 tablespoon of kosher salt in 1 cup of water and adding it to your ferment.

Q: How can I test to see if my fermented foods are ready?

A: The best tool for testing the readiness of your fermented food is your taste buds. Don’t be afraid to try the food as it moves through the fermentation process — it’s not harmful to eat the food at any stage. After about a week or so, you can remove a cucumber from your brine, slice it in half, and look inside (even sooner if you are fermenting in the heat of the summer, when the process goes much more quickly). It should be fairly uniform in texture, with no unfermented core at its center. If it looks good, give it a nibble. If it is pleasantly tart to you, you are done. If you would like the pickles to have a bit more pep, leave them for a few more days. When they taste as tangy as you want, put them in the fridge, submerged in their brine. Keep in mind that they will continue to pick up flavors from the brine as they sit in the fridge. And, although the cold of the icebox will slow fermentation, it won’t completely stop it. So your pickles or kraut will get a little stronger with age.

Q: How much water should I add to my sauerkraut brine?

A: Sauerkraut uses the dry salting method — the chopped or shredded produce is tossed with salt, which leaches liquid out of the cabbage, creating its own brine. Only if you have a particularly dry head of cabbage, do you need to add any liquid at all. If after 24 hours your shredded, salted cabbage has not released enough liquid to be submerged, you can top off the jar with a little brine. To make the brine, dissolve 1 scant tablespoon of kosher salt in 1 cup of water.

Never add plain water to fermenting foods. It will dilute the salinity of the brine, which may lead to less desirable results.

Making sauerkraut

Q: A mouse died in my crock. How can I keep that from happening?

A: It is really important to cover your crock so that pests cannot snack and/or swim on or in your ferment. The best way to do this is to drape a tea towel or double thickness of cheesecloth over the top of the crock and then secure it with a rubber band or similar band to keep it tightly fitted around the top of the container. Alternatively, I have heard from fermenters that they have fashioned a stainless steel screen that fits the top of their crock, which allows air in and keeps pests out. Either way, you don’t want visitors in there, so cover it up.

Q: Wow, this stuff is smelly! Is that okay?

A: Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, I suppose. Fermenting vegetables do have a strong smell. Some love it and others, not so much. But if you think the fermenting crock is fragrant, you should put your nose in my cheese drawer. Woof! I would suggest that when fermented foods played a larger role in our diets, we were more accustomed to the way they smelled and weren’t as put off. Perhaps once you get in the fermenting habit, you will feel the same. Until then, if you need the slow ramp-up on the fermenting fumes, you might consider putting your crock in the garage to do its work. Who knows — maybe eventually, it will be invited inside to stay.

If you have never fermented before, use a glass jar rather than a clay crock, at least for your first few rounds. It allows you to see what’s going on inside the ferment so that you can better understand the process (and enjoy the kitchen science).

Makes 2 quarts

This is one of my favorite recipes to demo: It’s part science experiment and part tasty recipe; and it is a great lesson in the magic of beneficial bacteria, for kids and adults alike! In a world full of endless ingredient lists on packaged foods, it’s amazing how much flavor you will get out of just a few humble items. A useful, though not essential, device for this recipe is a kraut board — a traditional tool for shredding cabbage, similar to a wooden mandoline.

Refrigerate: Store in the refrigerator, covered, for up to 1 month.

Q: What kind of container is suitable for fermenting?

A: Never use anything but a food-grade container for fermenting. Glass, ceramic, or food-grade plastic is fine. Never use a recycled container — such as a paint bucket — for fermenting. Such containers can transfer trace amounts of their previous contents or leach chemicals from the plastic itself into your food.

Q: I live in an apartment in New York City. Can I ferment foods in my kitchen or do you need a basement?

A: Many eaters ferment in their basements, where the cool, constant temperatures make it easier to regulate the fermentation process. But a basement or even cool temperatures aren’t necessary to successfully ferment your produce. In fact, some practitioners of the process swear by the antiseptic action of strong sunlight and always set their crock where it can catch some rays. If you are fermenting in your kitchen, or anywhere where the temperatures will be 70°F and above, you might add a bit more salt to your mix, as it will slow the process considerably.

It is easiest to control a ferment in an environment that is not subject to extreme temperatures. A hot kitchen in the middle of August may not be the best. But you don’t need a basement to ferment your own food, and many of my city friends do just fine at a normal room temperature of 68°F or so. Just keep in mind that higher temperatures will speed fermentation and cold temps will slow it down.

Q: I’ve heard that you can use leaves to keep fermented pickles crisp. Is this true?

A: Not only can you use leaves to keep your fermented pickles crisp, but it’s one of the best tricks in the book. The leaves to use are those that contain tannins, such as oak, cherry, and grape leaves. Don’t use too many or the tannic taste — which is responsible for that dry-mouth flavor of over-brewed tea — will overpower your pickles. A small handful — three or four large leaves, or up to six small ones — will crisp your pickles without throwing off the flavor of your brine. I ferment in a clear glass jar and the leaves, mixed in with the garlic, spices, and cucumbers, look great, too.

Q: What kind of salt should I use for fermenting?

A: As with all food-preserving processes, you want to use salt without any additives, which can affect the color or flavor of your foods. Ordinary table salt is often treated with anti-caking agents to help it flow more freely in the shaker, and iodine, a dietary supplement. I use kosher salt for all of my preserving recipes — it’s readily available and additive-free. Some preservers swear by the nutritive benefits of sea salt and prefer to use that in their recipes. I would avoid sea salts that contain high amounts of minerals — such as black salt — that could interfere with your results. Save these flavorful and gorgeous salts for seasoning foods on the plate. (See A Glossary of Salt)

Q: I am on a low-salt diet. Can I use a salt substitute in my ferments?

A: Salt plays such an important role in fermentation, keeping pathogens at bay so that the beneficial bacteria can do their work of creating the lactic acid that pickles the produce. While you don’t need to use specialized canning salt to get good results, fermenting without any salt would be tricky at best, and it is not recommended by the USDA.

That being said, Sandor Katz, who is a well-regarded authority on fermentation, suggests that you can ferment using wine, herbs, and seaweed as alternatives to salt to control contaminating pathogens.

Q: Can you ferment fruit?

A: Sure — it’s called wine! The high sugar content of fruit makes it hard to ferment without turning into alcohol. It can be done, however. Moroccan pickled lemons are one example. The fruit is cut and filled with salt and then packed tightly into jars and allowed to cure in the sun until the skins are softened. The salt flavor is strong, though, so it is usually rinsed off the fruit before the lemons are used in recipes.

Q: I would like to add some different vegetables to my sauerkraut. Is that okay?

A: Fermentation isn’t just for cabbage and cucumbers. Lots of vegetables taste great when fermented and can be used instead of, or in addition to, your kraut recipes. Carrots, ginger, radishes, and daikon are just a few that come to mind that would be particularly tasty in a sauerkraut preparation. I recommend shredding them either in a food processor or on a mandoline to ensure that the cabbage and added vegetables ferment evenly.

Just be sure that whatever produce you use, it remains completely submerged under the brine during the fermentation process. If the mixture you choose does not exude enough liquid to create its own brine, top off your crock with a mixture of just under 1 tablespoon of kosher salt dissolved in 1 cup of water.

Q: What kind of water is best for fermenting?

A: If your tap water is suitable for drinking, you can use it for fermenting. If you live in an area where the water is heavily chlorinated, you might consider boiling it and bringing it to room temperature to evaporate the chlorine before proceeding with your recipe. You can also use bottled or distilled water for fermenting.

Q: How do I know whether I should salt my produce or add a brine to ferment it?

A: Sprinkling your produce with salt, also known as dry salting, extracts the natural juices from produce to create its own brine. It’s a process generally used for chopped or shredded fruits or vegetables, where the high ratio of surface area allows the salt to act on the produce quickly. The salt draws out the juices and the produce is effectively submerged under brine created by its own liquid.

Foods that are submerged under liquid brine are often those that are left whole, such as cucumbers. Due to their large size, it would be hard to encourage these foods to release enough of their own liquid to submerge them in the crock. To create a fermenting brine, dissolve kosher salt in water in a ratio of 1 scant tablespoon of kosher salt in 1 cup of water.

Q: How do I know how much brine to use?

A: You need to completely submerge your produce under the brine for it to be effective. But the volume that you make depends solely on the amount of produce you are fermenting and the size of your crock. You don’t have to think of it as an exact science; just mix up a batch and pour it into the crock. You can add more if you need to get the produce well submerged. As long as you stick to a ratio of just under 1 tablespoon of salt to every cup of water, you can scale the volume as you need.

Q: Can I use different spices in my fermented foods?

A: Yes, you can use spices to change the flavors of your fermented foods. Many different cultures have their signature combinations. Kimchi uses chiles and ginger. Caraway is a popular addition to sauerkraut in Germany. But you can feel free to experiment. Try peppercorns, coriander seeds, juniper berries, or a few cloves. Keep in mind that mild flavors, such as lemongrass, may become subsumed by the strong flavors of fermented foods.

Some spices, such as turmeric, are antimicrobial. This will not affect the ferment, however; the lactic acid bacteria working to keep the food safe and give it its signature tang is a hardy breed. In fact, such spices can actually help the process by staving off contaminating molds.

Q: Can I add raw fish to my kimchi to flavor it?

A: Raw fish is a traditional addition to kimchi that gives it a signature umami, or earthy, meaty, flavor. If the prospect of using raw fish in the mix is a bit daunting, you can still get the earthy flavor with some less intimidating ingredients. Try a small amount of dried shrimp (available in Asian markets), anchovy paste, or even Worcestershire sauce, which contains anchovies as one of its main flavoring components. Vegans and vegetarians might consider a bit of rehydrated seaweed in the mix to get a similar flavor without any animal products.

Q: How salty should my brine be?

A: Fermentation is not an exact science. There are guidelines for success, but not a precise formula; much of it is a matter of taste. One traditional rule is that your brine should be strong enough to float an egg. But if you have ever tasted such a brine — or food prepared with it — you might agree that this amount of salt is too intense for modern tastes. A 5 percent brine will get the job done and is more in tune with modern palates. This means that you are using 5 percent of salt to water, by weight. Varying salt grains will give you different weights per measure — the finer the grain, the heavier it is by volume — but a good rule of thumb is just under 1 tablespoon of kosher salt per 1 cup of water, or 3 tablespoons of salt per 1 quart of water. You can lower the salt a bit, and doing so will speed your fermentation process. You can increase it, too, and that will slow the fermentation.

Q: Why are my pickles hollow?

A: Hollow pickles can be caused by a number of different things. One of the most common reasons for a hollow pickle is that they were pickled too long after harvest. It’s important that cucumbers make their way to the fermentation crock as soon after picking as possible. Even a day or two can lead to disappointing results. Another reason is that the cucumbers may have been left too long on the vine. Old cucumbers will have a hollow core, which can be hard to detect when you are fermenting them whole. Use produce that is at its peak of ripeness for fermenting.

Q: I have some grapevines in my backyard. Can I pickle the leaves?

A: Absolutely! Pickled grape leaves are delicious when stuffed with all manner of different fillings. The best leaves to use are the young, tender spring leaves. Pick them just when they get big enough to hold a bit of filling. Opt for the leaves of white grapes, which are more succulent than the leaves of red grapes.

The best way to preserve them is to ferment them. Make a stack of 12 leaves and roll them up like a cigar. Repeat with 24 leaves to make 2 more rolls, packing them in a clean quart glass jar as you go. Submerge them under a simple brine of 1 scant tablespoon of kosher salt dissolved in each 1 cup of water. Weight down with a small jar and cover with a tea towel. Allow to ferment until the leaves are pliable and tangy, about 1 week. Refrigerate until ready to use.

Q: Can I can my fermented foods?

A: Technically, yes, you may can fermented foods. The lactic acid that forms in the process will drop the pH low enough for fermented foods to be processed using the boiling-water method.

However, the heat of the canning process destroys one of the best benefits of fermented foods: the beneficial bacteria created during the process. This beneficial bacteria, like that in yogurt, is terrific for your digestion. Probiotic foods like fermented pickles and krauts, and yogurt and kefir, have long been valued in traditional cuisines for their multiple health benefits and are gaining popularity in modern science’s approach to health. Refrigerate these products to prolong their shelf life and enjoy them, as they are — alive and well.

Q: I have my fermented pickles in the refrigerator. That stops the fermentation, right?

A: Actually, refrigeration only slows fermentation; it doesn’t stop it. Your pickles, kraut, or kimchi will continue to ferment, but at a greatly reduced rate. Be sure to check the jar periodically, dipping off any bloom that forms on top of the brine. Top up the brine as necessary to keep all produce fully submerged.

Q: Can I cook with fermented food?

A: You can, but keep in mind that one of the biggest benefits of enjoying fermented foods is the probiotics that they provide. These beneficial bacteria cannot survive heat, so any cooking will destroy them. The food will still taste good, but it won’t pack the probiotic punch of raw, fermented foods.