Visual Literacy Class in Human Rights

Ariella Azoulay

The apparent opposition between the two superpowers during the Cold War, the United States and the USSR, masked a disastrous agreement made by the Allies. The Allies’ consensus was to break the world down into small and weak units of nation-states. The right to self-determination and the right to safe boundaries (what the Atlantic Charter described in 1941 as “dwelling in safety within their own boundaries”) – along with the right to use violence to enact both – became the ultimate justification for parceling the world. Human rights discourse served as the mechanism for distinguishing state violence from other kinds of violence, and the establishment of the United Nations was instrumental in making the nation-state the only desirable and acceptable political model.

In the late 1930s and 1940s, World War II was an opportunity for the colonial and imperial powers to anchor themselves in sharp opposition to the Nazi and fascist regimes. Through this opposition, the superpowers could now present themselves as the harbingers and guarantors of a “new global order:”

after the final destruction of the Nazi tyranny, they [US and UK] hope to see established a peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford assurance that all the men in all lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.

(Roosevelt and Churchill 1941)

In the Atlantic Charter, Roosevelt and Churchill made a commitment that is expressed in a variety of founding papers in the field of human rights. They committed to “respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them” (Roosevelt and Churchill 1941).

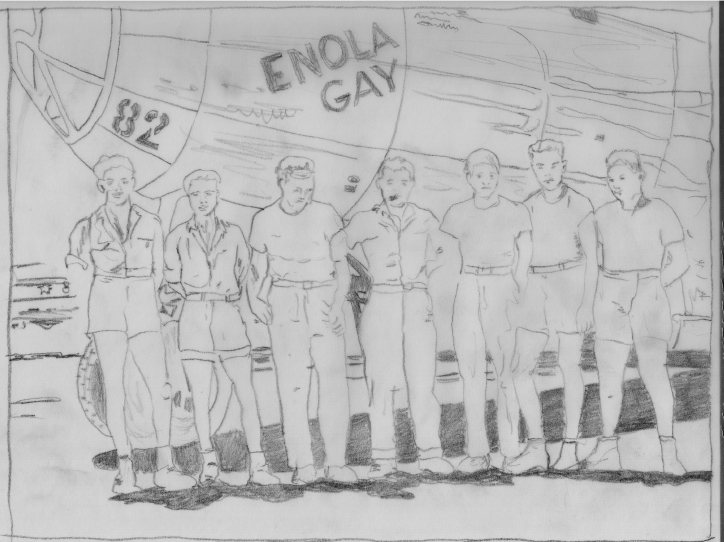

When this commitment is discussed in human rights discourse, it is typically asked whether it was fulfilled or broken with respect to certain populations. My focus in this paper is on a slightly different topic: the commitment to human rights as a way to construct a scheme of global rule, a scheme mediated by the United Nations that became part of modern sovereignty. In the first two sections of the chapter I will show that the UN’s explicit goal from the start was to make sure that all political formations in the world would conform to, and be contained within, its standard models of sovereignty and human rights. In the third section of this chapter, I will focus on the global teaching of “visual literacy” conducted by the Allies. At the core of the Allies’ global “curriculum” were two tenets: first, the now-institutionalized distinction between legitimate and illegitimate violence, and second, the distinction between intentional violence and violence exercised as a necessary means for maintaining world order and peace. Photographs of victims’ bodies, detached from the industry of violence that produces them, were the preferred materials used in teaching human rights. Other images – e.g., cakes in the shape of Hiroshima mushroom clouds – were deemed irrelevant in this course on human rights.

The “Cold War” narrative of opposition

The abstention of the USSR and other “Soviet bloc” countries from voting on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 is often explained by the diverging approaches of the two blocs to the question of human rights – a divergence assumed to be an implicit part of the Cold War. In a recent book, Petra Goedde adds to this common narrative of opposition another incident that illustrates Cold War polarity: “at the very moment of the adoption of the declaration in New York, the United States brought accusations of human rights violations against the Soviet Union before the United Nations” (2014: 652–53). The reason was the blockade of “all traffic between the Western-controlled parts of Berlin and the Western Zones of Germany in protest over the currency reform implemented by the Western Allies” (Goedde 2014: 653).

Counterexamples to the narrative of opposition between the superpowers, like their agreement on the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, are viewed as exceptions to the rule. The dominance of this narrative of opposition between the US and USSR in part legitimized their status as “superpowers,” enabling them to occupy others, draw arbitrary lines within social and cultural fabrics and partition territories accordingly, divide, displace, and subjugate populations to their rule as deemed necessary – and to hold subjugates to the colonial powers’ standards, terminology, visions, and models. The superpowers used violent mechanisms to divide the world into two blocs that were in turn subdivided into weak sovereign states. These mechanisms enabled the superpowers to enforce their rule across vast populations. The particular discourse of human rights promoted by the UN – an organization that unites states that rule differentially over their populations – left millions clamoring for human rights. As Mark Mazower and Robert G. Moeller have shown, for example, the transfer of 12 million Germans who were forced to move from East to West under agreements achieved between the Allies, or the transfer of the majority of the Palestinian population from Palestine as part of the creation of Israel as a nation-state, were at the outset not considered violations of human rights, but rather necessary policies (Mazower 2009; Moeller 2001).

The fact that these violent mechanisms were also employed by the quasi-states that were granted freedom by the imperial powers is not coincidental, but symptomatic of the strong link between human rights and the right to self-determination in the post-WWII nation-state model. The founding documents of human rights, drafted during the war and immediately after, were implicated in this massive uprooting of peoples and the legitimization of the new colonial order. I propose to read these documents alongside the mechanisms of violence that the pioneers of human rights used authoritatively and without irony (i.e., as if the use of such mechanisms were not a violation of people’s rights). The disagreements – or agreements – between the East and West on particular rights, I argue, is secondary to the fundamental agreement on the basic doctrine of human rights advocated by the UN and imposed on new member states as rules of the game.

In his book The Last Utopia (2010), Samuel Moyn renders the question of the agreement or disagreement between the US and the USSR vis-à-vis human rights superfluous – arguing that human rights did not play an important role in their relationship in the 1940s and, indeed, not globally until the 1970s.

Moyn points to many contradictions in the use of the concept of self-determination and human rights in the 1940s and beginning of the 1950s, concluding that

if the United Nations had a strong impact on decolonization, it was not by design … . It would have been impossible to predict in 1945, or even in the brutal postwar years when the Universal Declaration’s framing was a sideshow compared to the world reimposition of empire.

(2010: 94–95)

Rather than trace the development and materialization of these ideas chronologically, I will instead outline their functions in imposing differential sovereignty within the nation-state model imposed by the UN. As President Roosevelt explicitly said, the UN is what gives these principles – life, liberty, independence, religious freedom, human rights, and justice – their “form and substance” (Roosevelt and Churchill 1941). It was not only form and substance that were guaranteed by the UN, but the power to regulate and standardize political aspirations, claims, and dreams within the limits of the one allowable – and construed as desirable – UN model: the nation-state. The extension of the principle of self-determination to all peoples through the use of “legitimate violence” bridged the gap between Wilsonian idealism and Lenin’s historical-progress assumption. The common ground for the Allies’ collaboration was their agreement that global power should be retained and shared by them, and the question how to divide the trophy was secondary to this basic agreement. The isolation of Berlin from other areas in East Germany that were under the USSR’s occupation, and its division first into four parts, as if to reward each of the four Allies with its share of the trophy, illustrates the effort to secure the Allies’ global domination. The legitimization of partition and forced migration as a means of global control became inseparable from the process of realizing people’s right to self-determination in nation-states.

The end of WWII was seen as an opportunity to instill a new world order that preserved the domination of principal, imperial, and colonial protagonists as moral, legitimate actors. The resulting UN-approved singular vision of new world order was meant to stifle competing local and regional models of rule. The singular vision also aimed to suppress imaginative civil exploration and experimentation with different political formations for cohabiting the world based on the heterogeneous traditions and customs of its inhabitants. In the prevailing historical paradigm, the transition to a new UN-approved world order in 1945 marked the end of the era dominated by WWII, and was ushered in by a sensation of a “new beginning.” But this sensation was not an ephemeral moment of celebration, a swift transition from dark to light. Rather, it was a prolonged and carefully crafted transition, enacted violently using the aforementioned policies.

“A better future for the world”

What was this “new” world order? Was it really new, and in what way? Why were the articulations of human rights, self-determination, and the modern nation-state taking place simultaneously? Were there other formations of rule possible? If so, what was the role of the United Nations in making these alternatives disappear? Who were the subjects of human rights, and what was the relationship between them and the guardians of human rights? How has the figure of “the guardian” of world affairs, held by the UN, affected the conditions by which criminal perpetrators are identified? Or, to phrase the question more succinctly, how has the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate violence been institutionalized and reproduced?

In order to start answering these questions, we must first recognize that since the early days of its inception, the UN was already instrumental in making sure that the rich and heterogeneous language of human rights, developed under colonialism and imperialism by those subject to differential rule, would be replaced by a unified and abstract language of rights – a language formulated in the idiom prescribed by the UN. The rich language of rights, which had been developed and used since the end of the eighteenth century – by a woman in 1791 who claimed her right to vote or to inherit her husband’s property, by a slave who claimed in 1799 his right to be paid, by an African American who in 1834 claimed his right to equal wages, by the people of Ghana who in the late 1920s claimed their right to participate in the British ruling power – was ignored and replaced by one authoritative idiom. The adoption of this idiom, marred by colonialism and imperialism, could be secured only by an organization whose members were recognized as peace-loving states, guardians of world order. The UN rights discourse of the new world order preserved the essence of colonial structure. At the level of the colony, the discourse ensures, as Cooper argues, that others “might try to learn and master the ways of the conqueror but would never quite get there” (Cooper 2002: 16).

On a global scale, the UN ensured that no other political model other than those promoted by the imperial actors would survive, in a way that the major political formations, key terms, and models generated by colonialism and imperialism would not be questioned. Thus, the foundation of the UN was not meant to assist the development of the existing heterogeneous political vernacular of rights, but to allow the incorporation of “a multitude of new and often very weak states into the international community” (Jackson 1990: 4). Or, more broadly, to execute on a global scale what I elsewhere call the triple principle of sovereignty, which comprises differential ruling, fait accompli and externality (Azoulay forthcoming). The source of power and wealth of the principal actors who founded the UN was an instance of differential ruling. This was not a new form of political governance invented by the UN, but a preexisting condition from earlier colonial rule that was simply maintained. Its preservation required the type of sovereignty that one may call popular sovereignty, but actually functioned as a differential sovereignty – i.e., as the sole legitimate type. For this, sovereignty had to be implemented as a fait accompli, as the political condition of any politics and outside of political struggles, i.e., an accomplished sole type with no competition. At the core of this model of sovereignty, as it was instituted through the French and American revolutions, is a “split body politic” that is ruled differentially. Differential rule permeates various domains of common life and is the outcome of inequalities, as well as the source of all subsequent inequalities. The UN was the organization that set the standard for differential rule as a fait accompli and made it a condition for nation-states seeking admission into its club. Thus, differential rule, without which colonialism and imperialism would never have materialized or survived, was construed not as an exercise of violence, but as part and parcel of the law of nation-states.

Finally, externality is the way in which the governed population is mobilized to sustain sovereign institutions as if they were external to their governed subjects, who take no or little role in shaping them. The many, whose lives are affected by them, play their part – invented and improvised, within the triple condition of sovereignty. The UN, though, was fundamental in “bridging” – to use Frederick Cooper’s term – “the classic division … between the ‘colonial’ and the ‘post-colonial’” (2002: 15). No wonder, then, that many of those states that were created during this transition were poor, weak, and often “quasi-states,” as Robert Jackson termed them (1990). Thus, criticizing the deprivation of certain populations or nations from acquiring a full state that is not only a “gate-keeper” (Cooper) or “quasi-state” (Jackson) is already the affirmation of the particular political model that was constituted as part of differential rule as the sole model.

This common narrative of human rights as a “moral and legal basis,” repeated time and again, as I have shown elsewhere (Azoulay 2014), is one of the greatest achievements of the new world order’s political campaign conducted during and after WWII. In this campaign, the human rights discourse promoted by the UN already appears as the only possible discourse of human rights. The authorship/ownership of human rights discourse by a representative body of nation-states, namely the UN, is usually not even questioned. This association became so obvious that the UN is frequently depicted as an innocuous and neutral instrument for implementing human rights, rather than a player with a vested interest in a particular discourse surrounding such rights.

What could be seen?

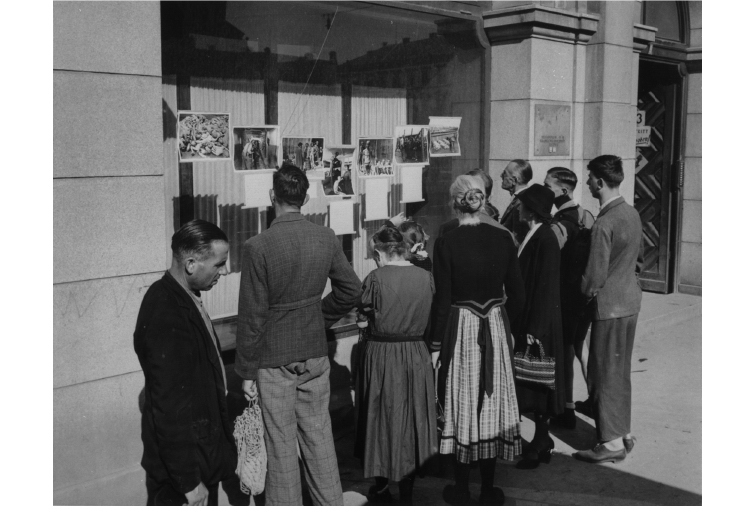

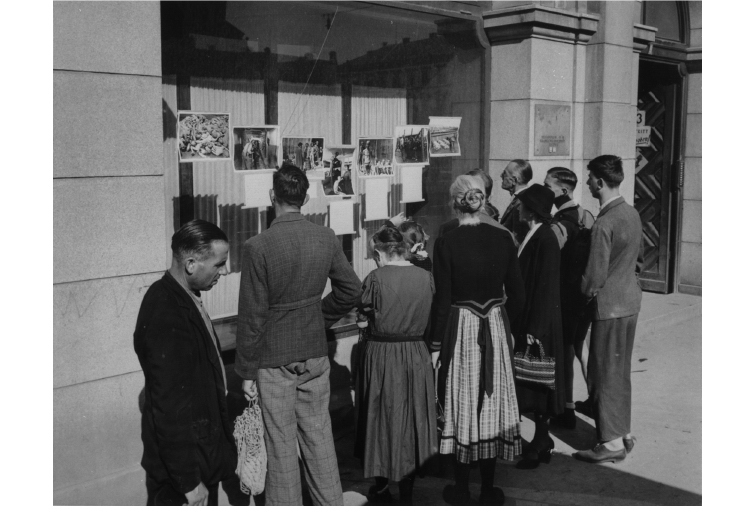

The UN and its five permanent member states (the “P5” states) used various platforms to conduct the visual literacy class in human rights, which included press conferences, photography exhibitions, pamphlets, posters, a ban on cameras, and education programs – to distinguish violence that constituted a human rights violation from legitimate state violence necessary to secure peace, order, and the rule of law. The objective was to instill in the public an internalized, personal sense of human rights – a sense that would produce widespread respect for and a commitment to the upholding of human rights generally and that would support institutionalized responses to violations of these rights. Whatever citizens were taught in class, it was often not in accordance with what they saw. The back-and-forth between annotated photographs and the catastrophic measures people witnessed first-hand had to be controlled in order to ensure the observers could correctly identify “legitimate” violations of human rights – and subsequently distinguish the human rights violators from their guardians. This had only partially to do with the images of catastrophe, and more with the accessibility of the images and the conditions that determined their legibility.

The three major catastrophes that were produced in 1945 by those who were also the world’s liberators from the Nazi regime – the annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the forced migrations of dozens of millions people, and the rape of millions of German women – were not construed as catastrophes that should have been condemned and stopped. The disaster in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was geographically bound, so the management of its containment and representation as a nondisaster was relatively easy. By contrast, the displacement of approximately 20 million people as part of the implementation of the postwar policy of self-determination was much harder for the international body to contain.

This displacement was enacted as part of the “solution” to the “problem” posed by “minorities” on the way to stabilizing a new world order. Refugees were viewed as either a “problem” or a “solution,” but never the consequence of abusive power by sovereign regimes or the result of human rights violations.

The postwar population transfer could not be criminalized, as those orchestrating it were also those running the class in human rights literacy – the ultimate arbiters of what constitutes a criminal human rights violation. These transfer disasters affected millions of people – those who perpetrated them, those who were their victims, and those who bore witness to them. It is only when these different positions of the disaster are assembled to form a whole that we can start to see the scope of what I call the “visual literacy class” in human rights. The primary aim of this class’s curriculum was to achieve a visual acceptability of catastrophic measures under the guise of policies and to hinder the possibility of assembling differential experience of these catastrophic measures to form a whole out of which a catastrophe can be seen for what it is. The inculcation of human rights under the principle of differential rule, reproduced through nation-states that incarnate this principle, affected the fate of superfluous populations, whose place within the existing body politic has not been acknowledged since. With the help of censorship mechanisms, like confiscation of books and films, looting of works of art, burning of newspapers – mechanisms overtly used for de-Nazification and promotion of sovereign discourse of human rights – a triple rupture was created. The rupture distorted three elements of the events in which human rights were violated: (1) the temporal sequence in which the violations took place, (2) the identities of the perpetrators, and (3) the position and role of the spectators who were implicated in the violations. The triple effect of the rupture was necessary to legitimize sovereign violence on a global scale. Without this triple rupture, the catastrophe of war might have ended and left the prospect for people to freely reconstruct the political conditions for sharing the world amongst themselves. The rupture also damaged the civil capacities – which were in some cases already lacking – for identifying violence by a standard independent of the international bodies that exercised the violence to begin with.

The massive campaign of photographic images from the liberation of the death camps in the United States and Britain, as well as in the camps themselves, is at the center of Barbie Zelizer’s book, Remembering to Forget. Zelizer argues that behind this massive campaign was the conviction that “the record of the camps’ liberation was mandated to be seen” (1998: 11–12). These images were shown as total exceptions to previous massacres, thus preventing the creation of a common ground from which to identify human rights violations; and the campaign commanded that they should not be compared to any other occurrences of mass extermination. The campaign’s goal, Zelizer argues, was to “go beyond the mere authentication of horror and to imply the act of bearing witness, by which we assume responsibility for the events of our times” (1998: 10). In contrast to Zelizer, I argue that when the grounds on which people account for such crimes is not common, and one crime is differentiated from another in principle and without the possibility to debate it openly, the capacity to assume responsibility for events happening under our watch is damaged. Bearing witness is depicted by Zelizer “as a type of collective remembering, [that] goes beyond the events it depicts, positioning the atrocity photos as a frame for understanding contemporary instances of atrocity” (1998: 13). Zelizer describes the propagandistic procedures used to disseminate such pictures, which included “strategic recycling” of certain images and calculated omission of others, and “governmental persuasion” (1998: 11). She does not question, however, the role of the witness in relation to the catastrophe that could have been seen or the carefully delineated boundaries of the catastrophe set by proponents of the new human rights doctrine. Almost a decade and a half later, Sharon Sliwinski returns to these images of the liberation of the camps, and argues that “indeed what these photographs engendered was something more akin to a paradox: the public bore witness in 1945, but they did not know what they had seen” (2011: 83). Sliwinski bases her claim on an historical reconstruction of the belated introduction of the term “Holocaust” into the discourse: “despite the profusion of pictures, it took several decades for the idea of ‘the Holocaust’ to find expression in public discourse” (2011: 84). Despite the absence of the idea, Sliwinski sees in these images the phenomenal manifestations of the Holocaust: “before the idea of the Holocaust entered public imagination, spectators found themselves gazing upon its image” (2011: 83). This argument is problematic historically and theoretically. In the Buchenwald camp, where more than 30,000 people died, there were non-Jews in addition to Jews. Non-Jewish Poles, Roma people, slaves, the mentally ill, and the disabled, as well as religious and political prisoners were among the piles of corpses depicted in these photos. The belated and inaccurate association of these images with “the Holocaust,” i.e., with the exclusive extermination of Jews by the Nazi regime, is not due to the images being images of the Holocaust – but rather due to an active campaign, the “Holocaust campaign,” which imposed a political vision upon the photographed catastrophe. The full meaning and consequences of such a catastrophe, however, cannot be gleaned by analyzing it through this forcefully imposed political interpretation.

The goal of the Holocaust campaign was to single out the extermination of the Jews, to set it apart from the Nazi extermination plans for other peoples, thus making it incomparable to other disasters (Zertal 2005). But even if the corpses recorded in the images were of Jews, images are never “of” an idea. An image can serve as fertile ground in which political ideas can be planted and grown, giving the illusion that these ideas arise naturally from the mere image. The absence of the metasignifier, “holocaust,” at the moment when people viewed these images for the first time does not mean that they were incapable of knowing what was in view. It also does not exclude other metasignifiers from being at play during the viewing.

The citizens’ capacity to identify and account for what they had seen, and elaborate their civil skills to recognize violations, was at risk at the end of WWII. Hunger, corpses, refugees, debris, loss, homelessness, and poverty were the sights that people encountered ubiquitously, while partaking in these sights as actors, extras, or spectators. Many of these catastrophic sights were concrete events that were not presented as images and did not depict past events of defeated regimes. These catastrophic situations and sights flashed rapidly in front of citizens’ eyes, in swift operations by the Allies to end the war. The organizing ideas of these sights were articulated through political key terms that had to be learned and ingrained: “peace,” “human rights,” “sovereignty,” “democracy,” “independence,” “war-ending,” and “world order,” for example. People were encouraged to view images as emanating from these ideas and to learn to recognize these ideas in the images.

Visual literacy is not just about photos. Human rights visual literacy is about the skills of the governed population to identify their role and complicity in the violation of human rights. Those classes conducted in the wake of WWII were intense, and photographs were used to demonstrate violations of human rights par excellence. In photographs, the depicted violations had already taken place and had already been documented as attributable to the crimes of others: violations by “them” not by “us.” The images of piles of corpses are a paradigmatic example, since the perpetrators were not only identified – “Nazis” – but already defeated by those who presented the photos. Visual literacy was thus also about instilling distance, the distance between “us” the spectators and “they” the perpetrators, as well as the distance between “us” the spectators and “they” the victims. Germans, Austrians, and Japanese were the exceptions to this dynamic of distance. They were rightly exposed to catastrophic measures that were either not photographed or photographed without being stamped as human rights violations. The Germans, Austrians, and Japanese were called to recognize themselves as perpetrators and bear collective guilt for the images that were branded as being “of” human rights violations. Voices of millions of people who were forced to leave their homes, and accounts of millions of German women who were raped, were excluded from the curriculum of the human rights literacy class, and started to be seen as such only decades later.

Photography was banned in Japan under US occupation, and only a few photos were released, including the famous mushroom cloud and some images of erasure in military books printed early in 1946, accompanied by technical accounts and no mention of the victims.

Through the exclusion of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from the discourse of human rights, we can learn about the nature of the human rights curriculum and the way in which it draws the lines between recognized and unrecognized human rights. This exclusion also teaches us about the expectations of those who possess the prescribed human rights literacy, the successful alumni of the class. The goal of the class was not to acquire and develop civil skills for recognizing when human rights are violated no matter the perpetrator or the justification, but rather to learn to recognize the distance relations within the actors depicted by the image – and to learn to appreciate our own role as caring, but still distant, spectators.

In Austria and Germany, dozens of press photographers were trained in the photographic “American model” and worked in US “opinion-research institutes,” the ISB (Information Service Branch) and USIA (US Information Agency) in their countries (Wagnleitner 1994). It was called “de-Nazification,” but it was an integral part of human rights literacy classes. The 12 million forcibly displaced Germans, for example, were not included by the photographers in the repertoire of human rights violations.

Figure 14.5 The Atom Bomb Cake celebration. Tracing by A.A.

A different reading of this type of images of violence construed as “policy” – e.g., “partition” or “repatriation” – by those classes was always possible. Through a reading of a single image of violence qua politic from 1947, in which a British official draws a boundary between the Soviet and British sectors in Berlin, W. J. T. Mitchell proposes a general scheme to read similar images. This very effective scheme that he terms “the dialectics of migration” guides how to undo the limits of the photographic frame: wherever a photograph is used to “show ‘exit’, read ‘entrance’, for ‘departure’ read ‘arrival’, for ‘nomad’ read ‘settler’, for ‘expulsion’ read ‘invasion’, or for ‘refugee’ read ‘detainee’” (Mitchell 2012: 131).

Ending WWII was not about recovering the “human condition,” necessary conditions for people to labor, work, and act together. Ending WWII was a massive legal, political, demographic, and cultural operation to naturalize the unlimited right of sovereign power to intervene in people’s lives in order to preserve differential sovereignty as the sole legitimate political formation.

If in the visual human rights literacy classes citizens were taught to develop an eye for recognizing human rights violations when they occurred, these citizens would have had the skills to join forms of resistance – resistance to massive evictions of people from their homes, to the waves of forced migration, and to the infringement on the freedom of movement of millions in their former countries. Citizens instead were taught to acknowledge – or ignore – such violations according to the way in which sovereign nation-states framed them – that is, as legitimate or illegitimate instances of violence. How many citizens actually resisted, in spite of the wide-reaching literacy class? We do not know, but we must assume their existence as part of civil resistance that the enforcement of differential sovereignty always provoked everywhere. Those citizens who did not internalize the lesson were often those uncounted by the differential body politic. Citizens of states who were appointed guardians of human rights were shaped in the image of the differential sovereign citizen, a subject whose rights – unlike those of noncitizens with whom she is governed – were protected by the nation-state. These “citizen guardians” were often unaware of the role of their citizenship in perpetuating this differential rule.

The photographic discourse of human rights shaped during and following WWII positions the spectator outside the situation of rights violations, and it positions the victim at the very heart of this discourse by attributing to the victim a place and a distinct voice. The discourse thereby implicitly conflates the subject of human rights with the visibility of the violation of such rights. The perpetrator is typically invisible in this configuration and can be therefore selectively abstracted, generalized, or demonized. Perhaps most importantly, this discourse poses a sharp distinction between these three categories of the perpetrator, the victim, and the spectator, and presents a clear division of labor among them. This division of labor positions the spectator outside the situation, disconnected from the perpetrator and the victim, and therefore absolves the spectator of any potential link to the perpetrator. Crucially, the spectator must be a sovereign citizen in order to be absolved from responsibility and enjoy the stamp of nonperpetrator. This scheme therefore rewards and reinforces the canonical model of nation-states that differentially offer such benefits to those governed as citizens under their rule.

When citizens are taught to misidentify forced transfers of people from their homelands, or their incarceration in refugee camps, as part of a legitimate sovereign plan and policy rather than a violation of human rights by that sovereign policy, their capacity to recognize such violations ultimately diminishes. Citizens gradually learn to obey sovereign policy because it is the law, rather than because the policy is just.

Further reading

Anonymous (2005) A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in the Conquered City: A Diary, New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt & Co. (A personal account of surviving in Berlin during Soviet occupation of 1945.)

Bernault, F. (2013) “What Absence Is Made of: Human Rights in Africa,” in J. N. Wassertrom, L. Hunt, and M. B. Young (eds.), Human Rights and Revolutions, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. (The colonial limits of the field of human rights.)

Glendon, M.A. (2002) A World Made New – Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, New York: Random House. (The behind-the-scenes of the drafting of the UDHR.)

Kelley, D. G. R. (2002) Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, Boston, MA: Beacon Press. (Thinking human rights from the perspective of reparations.)

Mitchell, W. T. J. (2012) Seeing through Race, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (An extended analysis of human rights, color, and visuality.)

References

Azoulay, A. (2014) “Palestine as Symptom, Palestine as Hope: Revising Human Rights Discourse,” Critical Inquiry 40(4): 332–64.

Azoulay, A.(Forthcoming) “Revolutionary Moments and State Violence,” in W. Chun, A. W. Fisher and T. Keenan (eds.), New Media, Old Media: A History and Theory Reader, 2nd edn, New York: Routledge.

Cooper, F. (2002) Africa since 1940: The Past of the Present, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goedde, P. (2014) “Human Rights and Globalization,” in A. Iriye, J. Osterhammel, W. Loth, T. W. Zeiler (eds.), Global Interdependence: The World after 1945, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Jackson, R. H. (1990) Quasi-states: Sovereignty, International Relations and the Third World, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mazower, M. (2009) No Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2012) Seeing through Race, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moeller, R. G. (2001) War Stories: The Search for a Usable Past in the Federal Republic of Germany, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Moyn, S. (2010) The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Roosevelt, F. ([1942] 2009) “The Atlantic Charter [One-Year Anniversary],” NATO e-Library. Available online at www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_16912.htm (accessed November 30, 2014).

Roosevelt, F. D. and Churchill, W. S. (1941) The Atlantic Charter, August 14. Available online at http://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/atlantic.asp (accessed November 30, 2014).

Sliwinski, S. (2011) Human Rights in Camera, Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Wagnleitner, R. (1994) Coca-Colonization and the Cold War: The Cultural Mission of the United States in Austria after the Second World, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Zelizer, B. (1998) Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory through the Camera’s Eye, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Zertal, I. (2005) Israel’s Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.