Becoming Human on the Terrain of Visual Culture

Keith P. Feldman

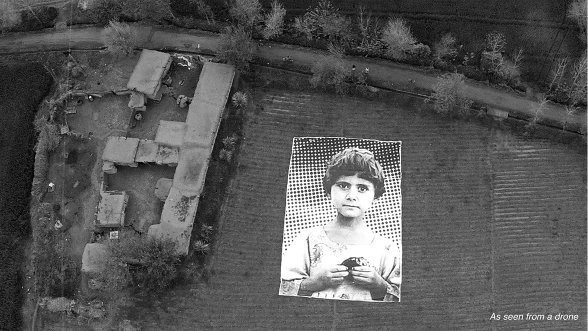

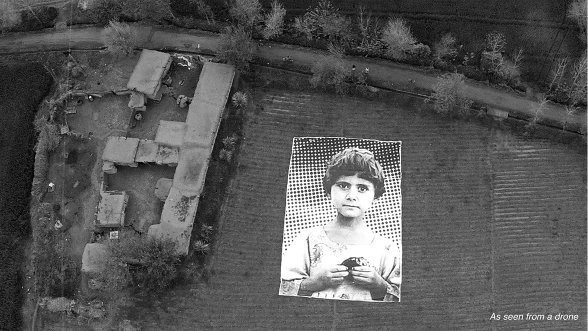

In April 2014, an oversized photograph of an unnamed girl holding a small stone, eyes squarely trained on the lens of the camera, began a new life of internet transit. Carrying the evocative hashtag #NotABugSplat, the photograph, 90 feet by 60 feet and printed on white tarpaulin, was displayed in a small undisclosed village in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region of Pakistan (#NotABugSplat 2014). The portrait of the young girl is based on a photograph taken by Noor Behram nearly five years earlier. Behram, a print and electronic media journalist, documented the aftermath of drone strikes in his native Waziristan, a region of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas in Pakistan, and a zone frequently targeted by US-led drone strikes. As Matthew Delmont (2013) notes, Behram’s images answer questions frequently obscured by the US War on Terror’s cultural grids of intelligibility: what are the grounded, embodied effects of drone strikes? What kind of archive makes visible a countervailing alternative to the War on Terror’s deadly imagined geography?

According to media accounts (Ackerman 2011), Behram took this particular photo on August 21, 2009 in the village of Dande Darpa Khel, arriving soon after a strike had demolished three houses, partially destroyed three others, and killed twelve people. Among the dead were Bismullah Khan, Khan’s wife, and two of their young children. Behram snapped a photograph of the children’s three surviving siblings, each holding a small piece of the ruins of their devastated home. This original photo, of the three siblings together, the youngest one looking plaintively towards his older sister, was subsequently included in a London exhibition of Behram’s prints documenting the aftermath of over 70 strikes, under the haunting title “Gaming in Waziristan” (2011).

#NotABugSplat provides an evocative example of the contemporary visual culture of human rights. It crystallizes the assemblage of production, circulation, and reception that utilizes the visual to advance human rights claims, and in so doing, it reveals the rhetorical and aesthetic ambiguity of such practices. The campaign was produced through a partnership between the Islamabad-based Foundation for Fundamental Rights and the London-based Reprieve, two transnational legal advocacy organizations. Lawyers affiliated with Reprieve had been involved in supporting the victims of a number of recent high-profile human rights violations. For instance, when in 2013 scores of men held indefinitely by the United States at Guantánamo Bay began a hunger strike to contest the terms of their incarceration, Reprieve was instrumental in making visible the brutality of their treatment, especially after the US medical team began the tortuous practice of force-feeding the strikers (Ferguson 2013).

On the formal level, the central portrait used for #NotABugSplat crops out the young girl’s two siblings, leaving an individual face of innocence, determination, and trauma to greet the gaze of the spectator. Its speckled background, black and white hue, and individuated figure signal its connection to French artist JR’s “Inside Out” project, a globalized initiative to place oversized portraits in public spaces. “Inside Out” makes visible an otherwise obscured human presence, one that activates both a heterogeneous historical memory and a democratization of everyday political imaginaries. When #NotABugSplat was launched, Inside Out counted nearly 200,000 people from 112 countries and territories among its participants (“Inside Out”). Captioned “as seen from a drone,” #NotABugSplat addresses drone operators directly by intervening in their typical visual field through an arresting alternative iconography. As the press release notes, “predator drone operators often refer to kills as ‘bug splats’, since viewing the body through a grainy video image gives the sense of an insect being crushed … . Now, when viewed by a drone camera, what an operator sees on his screen is not an anonymous dot on the landscape, but an innocent child victim’s face … . It is [the artists’] hope that this will create empathy and introspection amongst drone operators, and will create dialogue amongst policy makers” (#NotABugSplat 2014). The release’s imperative mood addresses its readers plainly: “Imagine the reaction of a pilot when on their screen, it’s not a bug but a giant face of a child staring back at them from the ground, engaging them directly” (Impact BBDO 2014).

#NotABugSplat was circulated via BBDO Pakistan, an advertising agency launched in Lahore in 2012 as a subsidiary of the New York-based BBDO, among the largest agencies of its kind in the world. In only a few weeks, according to BBDO, #NotABugSplat’s widespread circulation garnered 104 million impressions in the news and 11 million impressions on social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (Impact BBDO 2014). For its rapid circulation and low cost of production, the campaign received commendation from the Cannes Lions Creativity Awards, the first of its kind for an agency in Pakistan (Andrew 2014).

In this way, #NotABugSplat emerges from a network of transnational partnerships between legal advocates, advertising conglomerates, and artistic media producers, that together use digital media to give visual form and content to their campaigns. I dwell on the specific contours of this particular campaign because it invites an immanent critique of the broader entanglement of visual targeting and humanitarian spectatorship. #NotABugSplat foregrounds the negation of the drone war’s negation of civilian life and livelihood. But it is neither the drone nor its operator that sees this image. The campaign purports to hail an abstract (as opposed to an actual) individual operator, someone who is in a real sense a fiction. As was widely reported, the tarpaulin was displayed in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa for only a matter of days, and its materials were repurposed for the needs of the village’s local residents. By contrast, the digital duration of the image far exceeds the poster’s actual presence in the Pakistani village. This temporal disjuncture reveals the campaign’s addressee as more properly the broad globalized public of digital media, with all the complex ambiguities such a public encompasses.

While it situates viewers of the image behind the operator’s screen, in the operator’s chair, seeing with the operator’s eyes, #NotABugSplat also draws upon the universalizing genre of humanitarian visuality, pleading for human recognition through the figure of an individuated girlhood whose innocence has been violated. In the process, the scale and perspective of drone warfare are rendered uncanny. Even as the narratives used to legitimate drone warfare are predicated on a rhetoric of “high-definition” precision, the massive enlargement of #NotABugSplat offers the fidelity of the gendered youthful face as a scene for the enactment of “dialogue, or even empathy.” And yet, to see through these eyes is to activate a structure of imperial spectatorship, one that brings to the fore an icon of humanitarian visuality – the singular girl barely surviving a warzone – through the drone’s deadly optical field. In the remainder of this chapter, I elaborate on this entanglement’s key tensions.

Homeland visuality

Among the US War on Terror’s key cultural features is its globalized logic and practice of visuality. Here I follow Nicholas Mirzoeff (2011), who theorizes visuality as a self-authorizing claim to imperial authority whose classificatory regime aestheticizes differential relations of power. From the overseer on the slave plantation to the imperial historian’s narrative telos to the contemporary counterinsurgency expert, visuality names the complex within which claims to authority are secured and naturalized.

The expansion of drones in the last decade iterates this logic of visuality in especially stark terms, as Mirzoeff rightfully argues. Like other notable features of the homeland security state – a widespread culture of surveillance (Andrejevic 2007), dense folds between war powers and police powers (Neocleous 2014), a manifold carceral archipelago (Khalili 2013) – drone warfare’s iteration of visuality blurs the spatiotemporal principles of distinction that seek a proper domain for the enactment of state violence. This visual regime employs an “actuarial gaze” (Feldman 2005) to convert the production and management of modernity’s long-standing sedimented force relations into categories of risk, calculability, and rationality that are the target of the homeland security state’s violence. That this conversion happens through processes of gendered racialization should come as no surprise (the absence of race from Mirzoeff’s analytic notwithstanding). Race, as W. J. T. Mitchell (2012) has argued, remains modernity’s ideal form and vehicle through which the knowledge of otherness travels.

Because modern forms of visualization render difference and alterity seeable and thinkable, Mirzoeff compellingly theorizes visuality as central to the apparatus of modern warfare. In the context of the homeland security state, which links processes of “racialization on the ground” to “racialization from above” (Feldman 2011), potential targets are often identified and adjudicated through the visualization of metadata, figuring human existence in forensic traces of social interaction. The Obama administration calls this an analysis of “patterns of life” (Cloud 2010), one that produces subjects through a calculative aesthetic abstraction.

Human rights visuality

As an alternative framework, human rights advocates often deploy narrative to give textured form and meaning to such abstractions. Doing so attempts to render the grieve-ability (Butler 2009) for forms of life in the crosshairs of state-sanctioned violence, especially for audiences themselves inextricably entangled with the expression of such violence.

Additionally, human rights advocates in the ambit of the War on Terror have focused much of their organizing and activism around the practices of abstraction that blur normative principles of distinction, making visible the propensity of state actors to engage in practices of embodied violation, dehumanization, and social, civil, and biological death. At the same time, like the visuality of the homeland security state, and like the medium of race, advocates of necessity rely upon the field’s “ocular epistemology” (Hesford 2011: 29). Human rights discourses and practitioners employ a grid of intelligibility that ambiguously centers “seeing as believing” as the privileged domain of knowledge. Wendy Hesford builds on the insights of transnational and postcolonial feminisms to demonstrate how visual knowledges often reproduce the structure of racialized and gendered hierarchies that bring into the West’s visual field recognizable signposts of a distant otherness. Such reliance on this type of recognition enfigures the object of the human rights gaze through the norms of Euro-American perception. It mediates the distance of human rights abuses through presumptive racialized and gendered distinctions, reproducing an evidentiary logic that garners the truth of violation through the reconstructed actions and intents of victims and perpetrators across the colonial difference.

The history of human rights visuality is thus coterminous with the history of European Enlightenment and the liberal logics that animate it. As Sharon Sliwinski (2011) demonstrates, since at least the decimation of Lisbon by earthquake and tsunami in 1755, the production and circulation of knowledge about, and an ethical response to, human atrocity has relied upon visuality to provide texture and meaning to the idea of human rights. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) envisioned an abstracted individual subject borne into inalienable universal rights that were formulated, codified, and institutionalized in the broad post–World War II Atlantic Project to maintain Euro-American hegemony. Crafting a pedagogy to teach how to see this universalism was central to UNESCO’s “Human Rights Exhibition,” staged first in Paris in 1949 and circulated widely for the next four years (“Human Rights Exhibition Project” 2014).

This bind underscores how human rights renders visible under the sign of European Enlightenment that which has been obscured by the structuring frames of colonial modernity. It visualizes a universalism sedimented in and produced by imperial cultures (Williams 2010). Through its objectifying gaze, the visuality of human rights renders seeable, knowable, and “humanized” the truths of a violation that at the same time brackets from critical inquiry the structured differentials of power that make such seeing possible. It refracts back a normative subject whose perpetration of violence is paradoxically also framed within the optics of colonial modernity. This means that dialogic or even empathic responses to human rights visions are not foreordained. Even if there were such responses, their content, meaning, and effects are hardly a priori ethical. As Sherene Razack (2007) has emphasized, empathy in the context of empire has the capacity to exacerbate a liberal divide between the civil enlightenment of Euro-American nations and the objects of former colonial rule.

An other-wise vision

In the present context, grounding the drone war in embodiment’s particularities becomes an analytical and political question, as well as one of perspective. The lexicon proffered by human rights provides one ambiguous path towards answering these questions. It offers a normative vocabulary with which to reconstruct violation towards the aim of justice. Human rights discourse produces an archive of names, ages, faces, personal accounts, patterns of sociality – an archive, that is, of humanization – through which to bear witness to the violence of abstraction. In this sense, human rights discourse brings violation into view through positivist evidentiary grounds. A second valence for the grounding of drone warfare is in the rearticulation of a territoriality otherwise obfuscated by imperial culture’s imagined geographies. Grounding drones means illuminating the embodied and emplaced realities to which they are appended, the circuits of knowledge, capital, and material that shape the vibrant heterogeneity of life itself (Chamayou 2015).

#NotABugSplat is thus informed by and intervenes in the ambiguous interface between the visual culture of human rights and the optics of the homeland security state, with gendered racialization operating as a foundational visualizing medium. It joins an array of cultural production that grapples with the doubled vision of violation and humanization. It travels alongside a form of human rights discourse that substitutes the abstraction of data with the density of narrative.

This mode of human rights visuality frames the raciality of the War on Terror as resolutely dehumanizing and responds by making claims on the epistemic terrain of the human. Sometimes, this mode employs the evidentiary discourses of human rights and international law, such as the Stanford/NYU Joint project “Living under Drones” (2012) or the Human Rights Watch report entitled “Precisely Wrong” (2009) documenting the use of drone missile strikes in Gaza. At other times, claims-making is articulated via a baseline conception of “humanity,” utilizing the circulation of first-person accounts such as the letter by Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel (2013), detained at Guantánamo Bay for more than 11 years, narrating the hunger strike that brought into view the intensively biopolitical subjectivation of the homeland security state. This mode also increasingly deploys data visualization. A high-profile example of this sort is the Pitch Interactive project entitled “Out of Sight, Out of Mind” (n.d.), which links the documentation of data regarding drone strikes to an automated aggregator of journalistic and humanitarian accounts of drone incidents. Here, the aesthetics of data visualization dovetail with their discursive proliferation.

A second mode relies less upon overdetermined human iconography or the liberal propensity for “humanization” and uses instead the abstraction wrought by the actuarial gaze to make available for critique, as opposed to obfuscate, its racialized and spatialized violence. For instance, the work of artist and cultural geographer Trevor Paglen emphasizes the satellites, drones, and “blank spots on the map” (Paglen 2009). Paglen produces culture work less concerned with the human object enframed by a discourse of violation and humanization than it is in making visible the infrastructural materiality meant to remain obscured. His work is joined by data artist Josh Begley, who has harnessed digital frames through @dronestream, a Twitter project to document all US drone strikes reported in the media, including, wherever possible, the names and ages of the people the drone strike killed. @dronestream is linked to an iOS application called “Metadata+” that provides a notification and a locational map to signify where a strike has occurred. Paglen and Begley denaturalize the abstracted infrastructure of the homeland security state by bringing it into the foreground and signifying on its material technologies.

A final mode of visuality disrupts the actuarial gaze’s grids of intelligibility, its will to lock in place, by seizing on the persistently relational, and always already heterogeneous, axes of race, space, and bodily communicability. Such work operates transversally to destabilize and denaturalize US imperial culture’s terms of reference. It renders visible blurred boundaries, as opposed to isolating their principles of distinction. It makes legible tangible touchpoints between and across seemingly discrepant contexts of racialization, using the body less as an object for empathic recognition than as a vehicle to circulate knowledge about invisibilizing forms of incapacitation.

Noteworthy here is the intersection between the 2013 hunger strikes at Guantánamo Bay and their complement taken up by people held in long-term solitary confinement in California prisons. The prison confines threats to security inside walls, bars, barbed wire, and, as is the case with so-called “security housing units” (SHUs), prisons within prisons. The carceral regime often transports such perceived threats, as is the case in California, to remote areas, places hard for family, community, and legal counsel to access. Invisibility is the name of the game. It is what former Vice President Dick Cheney once called “time in the shadows” (quoted in Khalili 2013: n.p.).

The 2013 California hunger strike made visible the incapacitating temporality of domestic indefinite detention central to the rhythm of the homeland security state. At the time of the strike, more than 2,000 people were serving “indeterminate” SHU terms because they had been “validated” by the prison authorities as members or associates of prison gangs. The international medical community agrees that severe and permanent damage is done to the psyche – that is, life in the SHU becomes akin to torture – after 15 days. According to figures included in an Amnesty International report (2012), more than 500 prisoners serving indeterminate SHU terms had spent 10 or more years in the Pelican Bay SHU; of this number, more than 200 had spent over 15 years in the SHU and 78 more than 20 years. Many people had been in the SHU since it opened in 1989. The knowledge that the hunger strikers brought forth from the shadows of the homeland security state changed the terms of the US debate about solitary confinement. Their acts evinced a plea for individual human recognition – such claims to humanity were evoked, and human rights organizations documented reports of their torture and abuse. At the same time, they operationalized a radical critique of the debilitating systems of confinement that transit across the sweep of the carceral state.

Taken together, projects to visualize the subjects of human rights remind us that these subjects require critical theorizing. The word “theory,” after all, has its roots in the late Latin theoria, meaning “a looking at” or “a viewing.” At its best, the work of visualization yields the potential for an ethic whose baseline is not simply or solely a shared inclusion in humanity. Such visions of inclusion have often capacitated liberal universalism’s violently racialized hierarchies. Other-wise visualizations of the human – ones rich in the flesh of embodiment and the narratives that provide its texture and signpost its infrastructure – bring into view a demand to recognize other possible futures in our midst.

Further reading

Abel, E. (2010) Signs of the Times: The Visual Politics of Jim Crow, Berkeley: University of California Press. (Abel elucidates the constitutive function of the visual in constructing racialized space in the United States.)

Chun, W. (2013) Programmed Visions: Software and Memory, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Chun’s work advances a critical lexicon to understand the intersection of new media, race, and visual culture.)

Fleetwood, N. (2011) Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, Blackness, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Fleetwood centralizes the problematics of racialized embodiment as aesthetic practice.)

Hartman, S. (1997) Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-making in Nineteenth-century America, New York: Oxford University Press. (Hartman offers an influential account of the historical pivot from slavery to freedom demanding the visual performance of banal forms of violence.)

Jenkins, H., Ford, S., and Green, J. (2013) Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture, New York: New York University Press. (The authors theorize why and how media objects move rapidly across platforms.)

Raiford, L. (2013) Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle, Durham: University of North Carolina Press. (Raiford provides a rich account of the varied rhetorical and political effects of photography’s deployment as part of Black struggles for civil rights and human rights.)

References

Ackerman, S. (2011) “Rare Photographs Show Ground Zero of the Drone War,” Wired, 11 December. Online. Available online at: http://www.wired.com/2011/12/photos-pakistan-drone-war/ (accessed August 29, 2014).

Amnesty International (2012) USA: The Edge of Endurance; Prison Conditions in California’s Security Housing Units. Available online at www.amnestyusa.org/research/reports/the-edge-of-endurance-prison-conditions-in-california-s-security-housing-units (accessed August 28, 2014).

Andrejevic, M. (2007) iSpy: Surveillance and Power in the Interactive Era, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Andrew, M. (2014) “At Last a Cannes Lion,” Aurora, July 4. Available online at http://aurora.dawn.com/2014/07/04/at-last-a-cannes-lion/ (accessed August 29, 2014).

Butler, J. (2009) Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? London: Verso.

Chamayou, G. (2015) A Theory of the Drone, New York: New Press.

Cloud, D. (2010) “CIA Drones Have Broader List of Targets,” Los Angeles Times, May 6: A1.

Delmont, M. (2013) “Drone Encounters: Noor Behram, Omer Fast, and Visual Critiques of Drone Warfare,” American Quarterly 65(1): 193–202.

Feldman, A. (2005) “On the Actuarial Gaze: From 9/11 to Abu Ghraib,” Cultural Studies 19(2): 203–26.

Feldman, K. (2011) “Empire’s Verticality: The Af/Pak Frontier, Visual Culture, and Racialization from Above,” Comparative American Studies 9(4): 325–41.

Ferguson, B. (2013) “When Yasiin Bey Was Force-fed Guantánamo Bay-style – Eyewitness Account,” The Guardian, July 9. Available online at www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2013/jul/09/yasiin-bey-force-fed-guantanomo-bay-mos-def (accessed August 29, 2014).

“Gaming in Waziristan” (2011) Available online at http://beaconsfield.ltd.uk/projects/gaming-in-waziristan/ (accessed August 29, 2014).

Hesford, W. (2011) Spectacular Rhetorics: Human Rights Visions, Recognitions, Feminisms, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

“Human Rights Exhibition Project” (2014) Available online at www.exhibithumanrights.org (accessed August 28, 2014).

Human Rights Watch (2009) Precisely Wrong: Gaza Civilians Killed by Israeli Drone-launched Missiles. Available online at www.hrw.org/reports/2009/06/30/precisely-wrong-0 (accessed August 28, 2014).

Impact BBDO (2014) “Retrieve Foundation, ‘Not a Bug Splat.’” Available online at http://impactbbdo.com/#!&pageid=0& subsection=2&itemid=45 (accessed August 29, 2014).

“Inside Out: The People’s Art Project” (n.d.) Available online at www.insideoutproject.net/en (accessed August 29, 2014).

International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic (Stanford Law School) and Global Justice Clinic (NYU School of Law) (2012) Living under Drones: Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan. Available online at www.livingunderdrones.org (accessed August 28, 2014).

Khalili, L. (2013) Time in the Shadows: Confinement in Counterinsurgences, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Mirzoeff, N. (2011) The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mitchell, W. (2012) Seeing through Race, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moqbel, H. (2013) “Gitmo Is Killing Me,” New York Times, April 15: A19.

Neocleous, M. (2014) War Power, Police Power, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

“#NotABugSplat” (2014) Available online at http://notabugsplat.com (accessed August 29, 2014).

“Out of Sight, Out of Mind” (n.d.) Available online at http://drones.pitchinteractive.com (accessed August 28, 2014).

Paglen, T. (2009) Blank Spots on the Map: The Dark Geography of the Pentagon’s Secret World, New York: Dutton.

Razack, S. (2007) “Stealing the Pain of Others: Reflections on Canadian Humanitarian Responses,” Review of Education, Pedagogy and Cultural Studies 29(4): 375–94.

Sliwinski, S. (2011) Human Rights in Camera, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Williams, R. (2010) The Divided World: Human Rights and Its Violence, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.