THREE

KING COTTON

The Cotton Plant and Southern Slavery

EVERYONE IN AVOYELLES PARISH, Louisiana, agreed that Platt Epps had no peer when it came to playing the fiddle. No one else could make the instrument sing as well as the “Ole Bull of Bayou Boeuf.” At balls, feasts, and festivals, his fleet bow and nimble fingers called forth tunes that moved people to dance. Whether “Jump Jim Crow,” “Katy Hill,” “Pumpkin Pie,” “Old Joe Clark,” or the “Virginia Reel,” his hands worked magic on wood and horsehair and gut. Always people clamored for more, and in gratitude they filled his pockets with coin. Platt Epps had no more appreciative an audience than the children of Holmesville. Whenever he passed through town, they surrounded him and begged him to play. Sitting on his mule, he sent the notes into the humid southern air and across the eardrums of his delighted little listeners.1

But if Platt Epps's gifted hands and their agile digits made the sweetest music, those same appendages failed him when he took up an equally important although dreadfully onerous task. Try as he might, he could not pick cotton as dexterously as he could play the fiddle. The hands that flew over the strings turned clumsy and leaden when they reached for the bolls. The fastest pickers walked between the rows and plucked with both hands, demonstrating a “natural knack” for the job. In one motion, each hand grabbed a boll, or pod, extracted its fluffy white fiber, and put it in a sack. But Platt could not keep pace. Not only did he need both hands for each boll, but the sack that hung from his neck swung clumsily from side to side, breaking branches and killing green bolls not yet ripe enough to pick. As often as not, Platt dropped the precious fiber into the dirt before he got it into the sack. Something in his bones, muscles, sinews, and nerves prevented him from picking with greater speed and coordination. As Platt concluded, “I was evidently not designed for that kind of labor.”2

The consequences of his inept body materialized when he toted his basket of cotton to the gin house and dropped it on the scale. Each time the load was drastically underweight, often by more than half. Rather than the standard two hundred pounds, it might total ninety-five. Edwin Epps, the master, at first forgave Platt because he was an inexperienced “raw hand.” But when practice yielded no improvement, curses and the crack of a whip followed. Stripped, lying face down on the ground, Platt absorbed the master's rage, lash after lash striping his buttocks, shoulders, and back. Platt, the master bellowed, you are a damned disgrace—you are not fit to associate with a cotton-picking nigger!3

Still Platt did not improve, and the disgusted master finally gave up and ordered him to work on other tasks. Eventually, he went back to the cotton field, but for now he hauled baskets to the gin house, cut and hauled wood, and, at the insistence of Edwin Epps, played his fiddle. Perhaps once a week the master returned, drunk and devilish, from a day's spree in Holmesville. Assembling his exhausted laborers “in the large room of the great house,” he ordered them to dance. “Dance, you damned niggers, dance,” he shouted, whip in hand, as Platt struck up a tune. And then Epps joined in, “his portly form mingling with those of his dusky slaves, moving rapidly through all the mazes of the dance.” Dance, niggers, dance! On some occasions they did not stop until late at night.4

Platt dreamed of escaping his nightmare. He prayed that God would deliver him from the tyrannical master, and he waited for an opportunity to escape. Often his hopes crumbled in the face of circumstances that he could not control, and he feared that he would live out his days in his Louisiana prison. When despair settled in, he took solace in his fiddle. At night in his rude cabin or on the bayou bank on a Sunday afternoon, its gentle “song of peace” carried him back to a place where his hands did not pick cotton, where loving arms encircled him, and where he was not the slave Platt Epps but someone else entirely: the husband, father, farmer, carpenter, fiddler, and free man Solomon Northup.5

The story of Platt Epps-Solomon Northup reveals in intimate detail the horrors of a slave economy that consumed the lives of so many African Americans during the nineteenth century—even a few, such as Northup, who were born free and later forced into bondage. Northup's story also illuminates a crucially important but insufficiently examined feature of that shattering experience: the centrality of nature.6 Because Solomon Northup worked the cotton fields and keenly observed those landscapes, his experiences and observations provide a window into the problem of nature and slavery in American history.

Nineteenth-century southern slavery unfolded from a symbiotic relationship between cotton and people. Synthesizing water, soil nutrients, atmospheric gases, and sunlight, cotton produced seedpods filled with a fiber that humans found enormously useful and profitable. To supply a growing trans-Atlantic market of textile manufacturers and consumers, southern cotton producers cultivated more of the plant, expanding its geographical range and furthering its existence. Human labor was integral to the plant-people symbiosis. Because farmers and planters in the South chose to cultivate cotton using African American slaves, the growth of cotton production there necessarily involved the enlargement of slavery.7

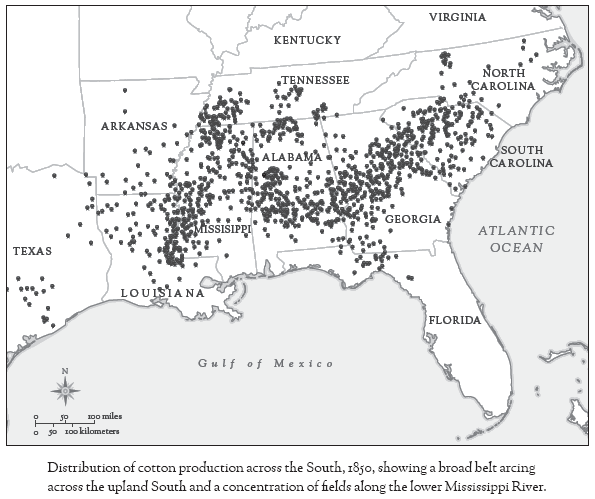

Between about 1790 and 1860, a conjunction of interdependent developments enabled growers to spread cotton plants throughout the South. The perfection of the saw gin, a muscle-powered machine distinguished by its fine-toothed blades, gave farmers and planters the means to separate extraordinary quantities of cotton fiber from cottonseed. At virtually the same time, the adoption of short staple (short fiber) cotton varieties suited to upland soils allowed growers to move their cultivation of the plant beyond the South Carolina and Georgia coasts. Meanwhile, the territorial enlargement of the United States—resulting from conquests, treaties, and settlement policies—opened up vast areas into which growers could expand. The movement of cotton followed two primary routes: from New Orleans up the Mississippi River and from the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia onto the Piedmont. By the 1850s, as growers clustered in areas with the best soils, most timely rainfall, greatest number of frost-free days, and readiest access to transportation, they formed a broad “cotton belt” that extended from North Carolina to Texas and along the Mississippi River from Louisiana to lower Missouri. The volume of fiber increased in proportion to the expanding range of the plant. In 1814-1815, the South put out some 363,000 cotton bales; by 1859-1860, the total had risen to 4.8 million, roughly two-thirds of the world's supply.8

As the number of acres and bales escalated, the demand for slaves shot up. When the United States banned the importation of slaves in 1808, the states of the upper South, most notably Virginia, became the major source of cotton labor. A “naturally growing” slave population, as one historian has observed, ensured upper South slaveholders a perennial, and profitable, surplus. The southward movement of human property was astonishing. Between 1790 and 1860, slaveholders transported about 1.1 million people from the upper to the lower South, some 875,000 of them in the years 1820-1860. The demand caused the price of bondmen to soar. The average value of a slave rose from about $300 in 1810 to some $800 in 1860, and the price for a prime male field hand in New Orleans reached $1,800. That same year, the worth of all slaves may have risen to $4 billion, making them the most important form of property in the South, more valuable than livestock and land, and the second most valuable form of property in the United States as a whole.9

The demand for slaves was so great that it enticed some traders to kidnap free people and sell them into bondage. In 1841, two strangers lured Solomon Northup from his hometown of Saratoga Springs, New York, with promises that they would employ him as a fiddler. In Washington, D.C., the men evidently drugged Northup and sold him to a Washington slave trader, who beat the unfortunate man into silence and transported him to the South. Northup's wife, Anne, soon learned of his abduction, and Northup secretly mailed a letter to a friend in Saratoga Springs asking for help, but neither Anne nor the friend knew of the enslaved man's precise location. It might have made little difference anyway, because by then Northup's captors had erased his identity, renamed him Platt, and put him up for sale at the New Orleans slave market. It was a horrifying experience. Northup witnessed the mental breakdown of Eliza, a fellow slave, when she lost her two small children on the auction block. Northup himself sold for $1,000 to a planter named William Ford. A “kind, noble, candid, Christian man,” Ford treated Northup well, and the enslaved man worked hard for the master. Ford's decency, however, did not keep him from selling his human chattel to pay off debts, and Northup eventually became the property of Edwin Epps.10

Solomon Northup's kidnapping was but one consequence of the dynamic symbiosis of plants and people that created the Cotton Kingdom, a vast apparatus composed of crops, fields, farms, plantations, laborers, technologies, laws, political institutions, ideologies, and economic arrangements. At the top of the kingdom were the slaveholders, people such as Edwin Epps but also far wealthier planters. At the bottom of the kingdom, straining under its enormous weight, were laborers such as Solomon Northup.

Given the kingdom's size and power, it might seem logical to presume that masters such as Edwin Epps ruled it with the ease and grace of the authoritarians they were proud to be. Yet this was not the case, for the slaveholders perpetually stood in danger of losing control. Their problems began with the cotton plant itself. The long rows that Solomon Northup and other slaves tended did not automatically yield the quantity or quality of fiber that growers desired. For various biological and environmental reasons, cotton resisted complete systematization and thus weakened the farmers' and planters' power over their kingdom. It is reasonable to speculate that southerners' use of a related term, King Cotton, subtly acknowledged that the plant had mastered them at least as much as they had mastered it.11

Slaves compounded the farmers' and planters' problems. Any environmental condition or biological process that the masters could not control or that disrupted steady production provided laborers with an opportunity to resist enslavement. Among the sources of conflict were the slaves' very bodies. Much as cotton resisted absolute agricultural discipline, so did the human organism. Solomon Northup's otherwise capable hands and fingers failed him when he tried to pick cotton, and no amount of whipping could make his body conform to the physical requirements of the job. Numerous other natural bodily conditions—disease, childbearing, exhaustion—prevented farmers and planters from forcing enslaved people to work longer and harder than they were physically able. The masters' dominance grew even weaker when Northup and other slaves consciously used their bodies as tools of resistance. Northup was a talented fiddler, and eventually that talent helped him to do more than just make music. Historians have said much about slave resistance, but they have said little about the ways in which it flowed from the organic nature of agricultural production—from both cotton plants and human bodies. Forms of resistant nature enabled slave resistance.

The environmental history of King Cotton can be told in two parts. The first describes the agricultural life cycle of cotton as it played out each year across the expanse of the American South. The second details the life cycle of the slaves who did the work of cultivation. The crop cycle of cotton was the point of struggle between masters and slaves, as masters tried to discipline slaves for agricultural work and as slaves resisted that domination. The botanical characteristics of cotton, along with environmental conditions that stressed or ruptured the crop cycle, intensified the master-slave struggle and opened opportunities for slave resistance. One of the greatest sources of stress in the crop cycle was the life cycle of enslaved people. From conception to death, human bodies had physical characteristics and needs that conflicted with the cultivation of cotton. Meeting those bodily needs detracted from the masters' ability to accumulate wealth and retain control of their human chattel.12

As we follow the organic cycles of cotton and bodies, the full story of Solomon Northup will come clear. The grand movements of nature and history coursed through him as they coursed through the lives of so many other seemingly insignificant people who inhabited the Cotton Kingdom before the Civil War. To examine his life is to witness on a local scale the forces that shaped an entire society. Northup, in sum, provides answers to questions about large themes lived small. How did it feel to lose your life to a plant? Despite the pain, was there beauty? What was it like to be chased by bloodhounds, to feel their bite? What was the taste of hoecake and hog fat on a humid day in July? Did hope have a sound? Did the notes of a fiddle set you free?

HURRIED BY THEIR CROPS

Of all the great cycles that shaped the history of the early United States, few were more powerful than the seasonal development of staple crops such as cotton. Inherent in germinating seeds, budding leaves, bursting blossoms, and ripening bolls was an organic process of such vitality that it could deflect the course of history. First and foremost, the dynamic crop cycle of the cotton plant was the medium of perpetual struggle between masters and slaves. Southern agriculturalists sought to discipline the bodies of slaves for the purpose of disciplining the growth of the cotton plant. Although the masters were successful in making both slaves and plants produce phenomenal quantities of cotton fiber, they failed to achieve the total dominance they desired. The inherent instability of the crop cycle, the environmental conditions that shaped it, and the very nature of enslaved people's bodies disrupted production and provided slaves with opportunities to resist the masters' designs. This process—the master-slave struggle with nature as its dynamic core—animated southern society and drove it toward a crisis that eventually threatened to undermine it.

Deforestation opened up the land for the crop cycle of cotton. Cotton production required the removal of the trees, vines, and brush that covered much of the South. On many farms and plantations, enslaved laborers cleared land during all seasons of the year, gradually bringing more land into cultivation. One summer activity was tree girdling, in which slaves cut through the bark of a tree, severing the tender cambium layer through which flowed the life-giving sap and killing the tree so that it eventually collapsed. Most forest clearing took place from January to early March, after the yearly harvest and before the warmth and sunlight of spring caused plants to begin growing again. During this late-winter interval, masters and overseers ordered field hands into the forest. Men wielded axes, felling trees and cutting logs into sizes that they could pile. Meanwhile, women and children grubbed brush and vines and added the woody debris to the piles. When nightfall precluded further clearing, masters and overseers assigned the slaves a task suited to darkness: igniting the piles and tending them while they burned.13

Soil preparation and planting followed the removal of wild vegetation. Newly cleared land had roots and stumps that interfered with the growth of tender cotton roots, so laborers first planted new ground in corn. The following year, after the remaining wood had decomposed and cultivation had loosened the soil, the land was turned over to cotton. On ground already devoted to cotton, the slaves' first late-winter task was to break down old stalks and pile them for nighttime burning. Then, in March, the slaves began plowing. A heavy share pulled by a team of oxen or mules carved deep furrows four to six feet apart, heaping soil between them to form a ridge. Around April 1, the laborers ran a lighter plow down the middle of the ridge, opening a space called the drill. As the plow proceeded, a sower followed, broadcasting cottonseed into the drill. Then a work animal dragged a toothed rake, called a harrow, over the drill, covering the seed with soil.14

With the cottonseed lodged in its soil medium, both the pace of work and the struggle between slaves and masters intensified. In seeking to discipline cotton to make it produce, the masters submitted to a kind of biological discipline. In effect, they subordinated their lives and fortunes to the dictates of a botanical clock—germination, maturation, and fruition—that marked the passage of time and determined all agricultural tasks. To meet the discipline of that clock—to raise the crop and protect it from weather, insects, and fungi—the masters increased their regimentation of their enslaved laborers.15 As the crop matured, the tempo and discipline of work increased. Anxious masters and overseers drove slaves to their physical limits, working them faster and for longer hours, demanding precision, and beating them if they showed any signs of slowing down or making mistakes. At such moments, hungry, tired, pained, miserable, and rebellious slaves were more likely to resist domination, and at such moments, nature often provided them with opportunities to carry out that resistance. Most important, slaves seized the opportunity presented by ripening cotton to wrest a margin of power from their oppressors. As cotton cells divided and the plant reached toward the sun, the bolls began to open, revealing their precious white fiber along with tiny pieces of a powerful thing called liberty.

Developments in the ground influenced the onset of the cyclical master-slave struggle. Masters hoping for a prolonged and thus especially lucrative harvest ordered their slaves to plant early. But if the seeds went into the soil too early and the weather turned cool and wet, the seeds remained dormant. Soil bacteria and fungi then preyed on them, and they rotted.16 If that happened, the master who wanted to get ahead ended up behind, and he drove his slaves all the harder to replant and make up for lost growth and lost time. Planting too early thus might cause the tempo of the work to begin accelerating sooner than normal.

Regardless, the tempo increased within five to ten days of successful germination. About mid-April, cotton sprouts poked from the soil. It was an anxious moment, for the shape of the future rested on the survival of those tender shoots. To nurture them, the slaves began a process of thinning and cultivation called scraping. Although the methods varied, scraping required great dexterity and skill. Using fingers, hoes, and a light “bull-tongue” plow, the slaves deftly thinned excess cotton shoots, creating rows of single plants spaced at roughly two-foot intervals. They also removed the sprouts of weeds and grass that, if left unchecked, might crowd if not overwhelm the cotton. Yet no matter how carefully executed, scraping could not compensate for uncontrollable and unanticipated natural occurrences such as late frosts and cutworms (caterpillars) that might destroy the crop.17 Returning to the fields early in the morning, the slaves might discover that a cold snap or an insect infestation had ruined their work. Then the crop cycle would begin again, but at a considerably more rapid and emotionally edgy pace.

In early May, some two weeks after scraping, and continuing through July, cultivation reached a fever pitch. During this time, masters and overseers found themselves locked in struggle with the unwanted vegetation that continued to sprout and thrive in open soil alongside the cotton. T. B. Thorpe, who reported on cotton production for Harper's Magazine, wrote that “grasses and weeds of every variety, with vines and wild flowers, luxuriate in the newly-turned sod, and seem … determined to choke out of existence the useful and still delicately-grown cotton.” The competing vegetation grew especially rank in wet years. Under such conditions, rain not only nourished the weeds and grass but also protected them from plows and hoes. Plows did not work well in muddy soil, and masters concerned about their financial investment in healthy slaves ordered them to take shelter when rain fell. “That was the devil of a rainy season,” observed the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who traveled widely throughout the antebellum South. “Cotton could stand drouth better than it could grass.” To Thorpe, the struggle was a “race” that cotton growers must win at all costs: “Woe to the planter who is outstripped in his labors, and finds himself ‘overtaken by the grass.’”18

To prevail over the grass, the masters and overseers increased the pressure on slaves. On small farms with a handful of slaves, some masters ordered their entire force—house servants, coachmen, the very old, and the very young—into the fields alongside the regular hands. During the early 1800s, the slave Charles Ball passed through South Carolina in the company of his new master and a group of fellow bondmen. While the party rested at a farm along the way, Ball heard the owner remark that “the planters were so hurried by their crops, and found so much difficulty in keeping down the grass” that they had to put all nine of their slaves in the field, including his “coachman … and even the waiting maids of his daughters.”19

On large plantations with dozens or perhaps hundreds of slaves, overseers ran hoe gangs along military lines. Charles Ball experienced such regimentation on a South Carolina plantation worked by some 170 field hands. The laborers woke well before dawn to the call of the overseer's horn. After assembling in front of their quarters, they walked to the cotton fields. At the edge of a field, the “captains”—themselves slaves—called the names of the slaves whom they commanded and assigned each a row of cotton plants. Captains and companies then went to work, each subordinate member being required to keep pace with the captain. Around 7:00 a.m., they stopped briefly for a breakfast of water and rough cornbread. At noon, they stopped again for the same fare, plus salt and one radish for each hand. Then they toiled through the remainder of the day and into the darkness, until they could no longer see well enough to continue. Once more the overseer sounded his horn, and the hoe gang returned to its quarters.20

Frederick Law Olmsted witnessed a similar spectacle decades later while traveling through Mississippi. A “heavy thunder shower” had just passed, and “from the gin-house to which they had retreated” appeared an impressive phalanx of sturdy field hands. At the front were some forty women, “the largest and strongest women I ever saw together,” wearing blue checked cloth around their bodies and colorful handkerchiefs, turban fashion, on their heads. Hoes over their shoulders, they walked “with a free, powerful swing.” Next “came the cavalry, thirty strong,” mostly men, along with a few plow mules. “A lean and vigilant white overseer” astride a pony “brought up the rear.”21

Violence kept the hoe gangs in line. Winning the struggle against unwanted vegetation required masters and overseers, in their judgment, to subject the enslaved laborers to rigorous discipline. Speed was of the essence; thus the slightest indication of tardiness, loafing, lagging, malingering, error, or incompetence required physical correction, even harsh punishment. The whip was the favored instrument, a tool arguably as important to southern cotton production as the ax, plow, or hoe. “Everything was in a bustle,” recalled Louis Hughes of the Mississippi plantation where he worked during the 1840s, and “always there was slashing and whipping.” Often slaves were required to keep up with the fastest hoer; if they fell behind, the lash came down. On the small Louisiana plantation where Solomon Northup toiled, the master required slaves to stay even with the pacesetter. If anyone fell behind or moved ahead, he or she felt the whip's sting. Northup and the other workers seldom satisfied the master. “In fact,” he said, the lash flew “from morning until night, the whole day long.” The intensity of the punishment sometimes depended on the nature of the ground the slaves worked. “Some fields are easy,” reported the former slave James Brown, and “some hard; some have more grass; others more roots; and it very often happens that the hands are hardest pressed where the land is most difficult to clean.”22

On some plantations, the master or overseer tried to break the slaves' solidarity and maximize their productivity by ordering one of them to mete out field discipline. If the driver proved insufficiently harsh, he or she received a whipping. This whip-or-be-whipped tactic inspired clever responses. When Edwin Epps handed Solomon Northup a whip, the enslaved man used a ploy to deceive the master. If Epps was nearby, Northup cracked the whip within a hair's breadth of his fellows, who “squirm[ed] and screech[ed] as if in agony.” When Epps was within earshot of the slaves' conversation, they made a point of grumbling about Northup's punishments. On some occasions, Northup and other drivers genuinely whipped other slaves when the master ordered; in other instances, they chose to absorb punishment rather than administer it. Assigned the role of driver on a frontier plantation in Alabama, James Williams agonized about punishing female slaves. “I used to tell the poor creatures,” he later said, “that I would much rather take their places and endure the stripes than inflict them.” Soon enough, he made good on his word.23

The violence that pervaded the struggle against weeds and grass often forced slaves into awful predicaments other than the one Northup and Williams experienced. One dilemma was that overseers compelled slaves to work quickly, which might come at the expense of working carefully. And care was often essential to their chores. If slaves did not perform tasks correctly, those tasks might not get done at all; performed imprecisely or recklessly, they might actually damage the precious cotton plants. Sometimes slaves had to choose between speed and care, and a wrong choice or hasty mistake would incur the wrath of a master or overseer.24

John Brown well knew the terrors. One morning on the Georgia plantation where he regularly endured brutal punishment, a mare in Brown's plow team became overheated in the sun. Intent on accomplishing his work, Brown failed to notice that the animal was ill. When he took her into the barn at noon to feed her, he saw that she failed to eat, but evidently he did not take this as a sign that something was wrong. About an hour after he returned to work, he finally recognized that the mare was in trouble. By then it was too late, and the animal “dropped down and died in the plough.” Before he told Thomas Stevens, the master, Brown tried to protect himself from punishment. Returning to the barn, he removed the corn from the mare's feed bin and replaced it with gnawed cobs from another bin. The ruse was successful, in that Stevens did not blame Brown for returning the mare to work without food. Stevens still blamed Brown for the death, however, and gave him a “very severe flogging.”25

On another occasion, Brown experienced the dilemma of having to choose between speed and care. While running a buzzard plow along the cotton to remove grass and weeds, the metal share came loose in the wooden helve that gripped it. A conscientious laborer might have stopped and repaired the device, since cultivation had to be done precisely so as not to injure the roots of the cotton plants, but Brown evidently did not believe he had that latitude. Nearly paralyzed, he tried to split the difference—he kept plowing, periodically stopping to push the loose share back into place. The tactic failed. Observing Brown's erratic progress, Stevens confronted him. When Brown bent over to show Stevens the share, the master kicked the slave “right between the eyes, breaking the bone of my nose, and cutting the leaders of the right eye, so that it turned quite round in its socket.” Another slave wiped away the blood, gently pushed Brown's eye into the proper position, and applied a bandage. The wound healed, but the eye was never the same.26

In some instances, the imperative of controlling grass and weeds intensified the master-slave struggle to the point that it became lethal. On the far western edge of the booming cotton frontier, the landscape was rough and the exploitation of labor especially harsh. Slaves who had performed household or specialized work in the upper South lacked the physical stamina necessary to endure the rigors of this rugged plantation environment and its overseers, who had few social or institutional restraints on their behavior. On a remote Alabama cotton plantation, an overseer named Huckstep terrorized James Williams and other slaves. “Very well!” roared the tyrant, whip in hand, as he stood before Sarah, one of the soft “Virginia ladies” whom he despised. The daughter of a white planter and a slave, Sarah was pregnant, sick, and unable to keep up with the pace of hoeing. Having absorbed one hundred lashes for her failure, she was now completely spent. “Nature,” Williams observed, “could do no more.” Yet Huckstep had no room in his heart for forgiveness. As she hung by her wrists from the tree, her body limp, the overseer prepared to escalate the punishment: “I shall bleed you then, and take out some of your Virginia blood. You are too fine a miss for Alabama.” After slicing off her flimsy garment, he stepped back and proceeded to apply the lash. When the second blow “cut open her side and abdomen with a frightful gash,” Williams could stand it no longer, and he cried out to the overseer to stop. Startled, Huckstep dropped his whip and told Williams to untie her. Williams and the other slaves carried the unconscious woman into the house, but they could not revive her. Within three days she was dead.27

Such violence in the service of rescuing cotton plants from weeds and grass provoked slaves to resist their oppressors, using techniques that ranged from verbal defense to physical defiance. James Williams's outburst momentarily disarmed Huckstep; in other instances, verbal defense was subtler. “You have a good deal of grass in your crop,” a southern “gentleman” told a “negro manager” as they surveyed the field for which the enslaved laborer was responsible. Much more than the slave's honor and pride was at stake; negligence could have dreadful consequences. The man deflected that potentially disastrous outcome with a cool, calculated response: “It is poor ground, master, that won't bring grass.” Slaves used equally subtle work techniques to resist their oppressors. Many laborers, for example, adjusted the pace according to the presence or absence of authority. If the overseer left for a moment, they slowed their toil; when he returned, they picked up the pace.28

When the labor of plowing and hoeing grass became too onerous, or when the violence that accompanied the work became intolerable, some enslaved people took drastic steps to protect themselves. Slaves fled bondage for many reasons, but among them was the deteriorating quality of life that accompanied the advance of the cotton crop cycle. Such was the case on the Alabama plantation where James Williams labored. “Soon after we commenced weeding our cotton,” he recalled, “some of the hands, who were threatened with a whipping for not finishing their tasks, ran away.” Such flight usually was temporary and created a kind of cooling off period in which masters and runaways renegotiated their expectations of work. While in hiding, the runaways often communicated with the masters through friends who served as intermediaries.29 In other cases, the resistance of enslaved people escalated the struggle as masters and overseers retaliated with still greater violence.

When that happened, resisters paid dearly for their transgressions. While traveling across a plantation in the lower South, Frederick Law Olmsted witnessed an overseer brutally beat Sam's Sall (probably short for Sally), a teenage girl who had fled her hoe gang and whom he caught hiding in a nearby forest. “Oh, don't sir!” she begged, lying face down on the ground as the overseer savaged her naked body with a rawhide whip. “Oh, please stop, master! Please sir! Please, sir! Oh, that's enough, master! Oh, Lord! Oh, master, master! Oh, God, master, do stop! Oh, God, master! Oh, God, master!” Outright insolence cost some slaves their lives. Big Harry, recalled James Williams, was a proud, physically powerful, diligent laborer who vowed never to submit to a whipping from Huckstep, the plantation overseer. After Harry threatened to kill him, Huckstep—fortified with peach brandy—pointed a gun at the enslaved man and ordered him to drop his hoe and “come forward” for punishment. Raising the tool above his head, Harry warned the overseer to “stand back.” As the other field hands watched in horror, Huckstep fired, and Harry fell across a row of cotton. “Oh Lord!” he groaned, and within minutes he was dead.30

Like the destruction of Sarah, the shooting of Big Harry was an unusual event, for masters and overseers—Huckstep included—could ill afford to take the lives of valuable laborers. Yet these incidents exemplify the extreme violence that could occur during a phase of the production cycle when cotton growers struggled to protect their crop from grass and weeds. Unwanted vegetation did not automatically incite murder, but it did make physical demands that escalated the master-slave struggle to the point that an enraged, drunken overseer could kill a weak or rebellious field hand. Creeping plants and brutality were linked in clusters of causal connections that could result in whippings or, in rare cases, deaths.

Rescued from grass and weeds, the cotton continued to mature. By July it had grown above the competing vegetation, its development foretelling the abundant harvest to come. “The cotton leaf is of a delicate green, large and luxuriant,” wrote T. B. Thorpe, and “the stalk indicates rapid growth, yet it has a healthy and firm look.” The height of the plant depended on soil type and other factors; cotton grown in the rich soil of river bottoms might grow above a man's head, while that raised in the leaner soil of upland pine forests would be smaller and shrubbier. Whether the plant was tall or short, a blooming cotton field was impressive. “There are few sights more pleasant to the eye,” stated Solomon Northup, “than a wide cotton field when it is in bloom. It presents an appearance of purity, like an immaculate expanse of light, new-fallen snow.” The colorful blossoms, which ranged from a rich cream to light purple or pink, lasted only a couple of days. As their petals faded and dropped to the ground, they left behind the ripening bolls, which in a matter of weeks would expand and split, a botanical transformation of profound social significance.31

Even now the plants were not safe, the cotton fiber not secure, the race not won. As the crop cycle neared its climax, a host of problems might still disrupt it, even wreck it. Although a powerful organic process drove the cotton plant to maturity, the equally powerful life cycles of other organisms intersected with, and fed upon, the life cycle of cotton. Unusually wet weather fostered the growth of fungal rust, which might destroy the cotton plant's leaves, and fungal rot, which might invade the boll, corrupting and consuming it from within. A moth species laid eggs that, when hatched, became the cotton worm, a caterpillar that fed on leaves and the tender boll. Whenever “these worms put in an appearance,” recalled Louis Hughes, they “raised a great excitement among the planters.”32

Of all the natural threats to cotton, perhaps none was potentially more disastrous than the army worm. T. B. Thorpe noted that the mature form of the insect, a seemingly innocuous brown moth, “would never be taken for the destroyer of vast fields of luxuriant and useful vegetation.” Yet those vast fields presented an ideal habitat for the moth and its voracious caterpillar progeny. In 1804, 1827, and 1839, army worms stripped foliage from “entire districts” of cotton. By the 1840s, conditions for the species had become even better. By then, cotton culture extended in unbroken swaths across the South, in a broad belt running from South Carolina west through central Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, and in another centered on the lower Mississippi River. In 1846, army worms “spread throughout the entire Cotton Belt, and such destruction was never before witnessed.” The caterpillars struck again in 1853, this time in conjunction with a fungal rot.33

Thorpe observed firsthand the army worm's impressive power, probably during the 1853 infestation, when a horde “attempted to pass from a desolated cotton field to one untouched.” Enslaved laborers had deepened a ditch between the fields, creating a barrier that might obstruct and contain the worms' advance. Through this “trench the caterpillars rolled in untold millions, until its bottom, for nearly a mile in extent, was a foot or two deep in [a] living mass of animal life.” The slaves then hitched an enormous log to a yoke of oxen, “and as this heavy log was drawn through the ditch, it seemed absolutely to float on a crushed mass of vegetable corruption.” To Thorpe, the brute organic magnitude of the event was not fully evident until the next day, when “the heat of a tropical sun” stimulated the decomposition of the caterpillars' remains. “The stench arising from this acidulated decay was perceptible the country round,” he wrote, “giving a strange and incomprehensible notion of the power and abundance of this destroyer of the cotton crop.”34

The army worm and other pests posed serious threats to the disciplined production of cotton, yet the disruption they caused did not necessarily ruin farmers and planters or intensify the master-slave struggle. In some cases, the wreckage caused by pest infestations stalled the escalating master-slave dialectic and provided enslaved people with fleeting opportunities to better their lives, even to escape bondage altogether. By destroying the crop cycle of cotton, the pests momentarily altered the terms of an oppressive social relationship.

So Solomon Northup found in 1845, after caterpillars nearly destroyed the entire cotton crop along the Red River. Northup's master decided to recoup some of his losses by renting his slaves to sugar planters on the Gulf Coast, who would pay him up to a dollar per day for each hand. The cane crop was ready to be harvested, and the planters needed help. Master Epps and the other cotton growers of Avoyelles Parish, their slaves idled by caterpillars, were happy to oblige. In September, Northup joined a drove of 147 Red River slaves on the march southward some 140 miles to St. Mary's Parish. There he was hired out to a Judge Turner, a wealthy planter whose land adjoined the Bayou Salle, which emptied into Atchafalaya Bay. In contrast to his poor aptitude for picking cotton, Northup had an innate talent for cutting cane. The work “came to me naturally and intuitively,” he recalled, “and in a short time I was able to keep up with the fastest knife.” Soon he was promoted to driver, whip replacing sharp instrument. Although cane labor was strenuous, it offered side benefits. Not only did Judge Turner pay him for working on Sundays, but the other planters rewarded him for the services of his fiddle. An evening performance in the town of Centerville once earned him seventeen dollars, a sum that made him nearly “a millionaire” in the eyes of the other slaves.35

Most important, a fiddling job in Centerville opened an opportunity for Northup to contemplate escape. A steamboat captain had brought his vessel up the Rio Teche to dock at the town. Northup overheard the captain say that he was a northerner, and this emboldened the enslaved man to ask the captain for help in getting away. Although the captain expressed sympathy, he would not allow Northup to hide on his boat. The risk was too great; if authorities discovered Northup on board, they would punish the captain and confiscate his vessel. The captain's refusal plunged the slave into despair, and he soon returned to the Bayou Boeuf. The incident had raised his hopes, however, and he began planning for the day when he would make good his escape. The agricultural ruin caused by caterpillars oriented Northup in the direction of freedom.36

When and where the army worm and other pests did not devastate the fields, the organic power of cotton drove the crop cycle to its climax. From late July to late August, the bolls on the bottom branches began to split open, and the wooly fiber was ready for picking. The pods on the middle branches ripened next. Finally, until autumn frost killed the plant, its uppermost layers continued to blossom and yield ripe bolls. Tensions ran high during picking time. An ample, high-quality crop promised great profits, and masters were eager to gather the harvest at its peak, before rain, dew, dust, or frost discolored it and before the shell of the pod grew brittle and cracked into woody fragments that stuck in the fiber. “I often saw Boss so excited and nervous during the season,” Louis Hughes recalled of his owner, “that he scarcely ate.”37

Under such conditions, masters and overseers ordered all available hands into the fields, including house servants, again whipping them onward. “The season of picking was exciting to all planters,” said Hughes, and “every one was zealous in pushing his slaves in order that he might reap the greatest possible harvest.” The work could be brutal. Hour after hour, the hands dragged their sacks down the rows, their backs and arms aching, the tender skin around their fingernails scraped, pricked, and lacerated by the sharp ends of the brittle pod, their blood threatening to stain the cotton and render it worthless. Each laborer was required to pick a minimum weight, and if he or she fell short, the master or overseer administered punishment, in some cases one lash for every pound below the standard. “With the fear of this punishment ever before us,” recalled John Brown, “it was no wonder we did our utmost to make up our daily weight of cotton in the hamper.”38

A combination of physical ability and experience enabled some laborers, called top hands or crack pickers, to gather the crop with extraordinary speed. Charles Ball believed that “the art of picking cotton depend[ed] not upon superior strength, but upon the power of giving quick and accelerated motion to the fingers, arms, and legs.” John Brown's gendered assessment essentially agreed with Ball's; although men's superior strength enabled them to carry heavy baskets of cotton more easily, women were faster pickers, because their more delicate, tapered fingers made them “more naturally nimble.” Perhaps a combination of controlled, forceful, agile movement impelled the splendid Patsey, an athletic young woman who drew Solomon Northup's admiration. No man or woman on the Epps plantation jumped higher or ran faster or chopped wood, drove a team, turned a furrow, or rode a horse more expertly. And no one, Northup asserted, matched her skill in picking cotton. When the production standard was two hundred pounds, Northup claimed that Patsey on occasion gathered five hundred. Because of the “lightning-like motion… in her fingers,” at “cotton picking time, Patsey was queen of the field.”39

Like no other phase of the crop cycle, the harvest magnified all the biological and cultural pressures inherent in cotton production. It was the masters' moment of truth, the yearly event in which they most conclusively demonstrated their dominance over their world. While driving their slaves onward, they gazed in satisfaction at the mounds of white fluff piling up inside their gin houses.

Paradoxically, the harvest also demarcated the limits of the masters' power. For all their efforts to control land and life, the masters never controlled the cotton plant exactly as they desired. They struggled to make it produce fiber more quickly and in greater, more easily harvestable quantities, but they were never completely successful. Cotton always imposed physical limits on their ambitions. To counter that botanical power, the masters responded in three ways. They tried to invent machines that speeded the harvest. Then they altered the nature of the cotton boll in an effort to make it meet their production goals; in effect, using natural hybridization and selective breeding, they tried to turn cotton's botanical power to their own ends. When these strategies were not completely successful, they tried to manipulate the size or efficiency of their labor force.

None of these options was simple or easy to accomplish. The first two were extraordinarily difficult. For various reasons, pre-Civil War cotton growers never created satisfactory picking machines.40 Southerners also experimented with cotton plants, but finding, cultivating, and disseminating new varieties required years of effort. Thus the most immediate, day-to-day means by which masters could counter the botanical power of cotton was to squeeze more work from their slaves. Yet this, too, had physical limits; slave bodies and the persons who inhabited them imposed restrictions on the amount of labor slaves could, and would, perform. To induce slaves to extract cotton fiber from the boll more quickly, masters found it expedient to concede to the slaves an additional slice of power.

This is how the process unfolded. As late as the 1830s, most southern cotton growers raised two varieties, Georgia green seed, introduced from the West Indies, and Siamese (or Creole) black seed, introduced from Siam, the southeast Asian country now called Thailand. Because the ripe bolls of these plants did not open wide, slaves, no matter how dexterous, could not easily extract their fiber. Besides the physical structure of the bolls, a range of natural conditions—the length of daylight, the speed and agility of human hands, the capacity of the human body to withstand fatigue—imposed absolute limits on picking. Fatigue also had a cultural component: the Sabbath. Six days you shall labor, the Bible said, and on the seventh, like God, you shall rest. Many slaves, moreover, devoted evenings and Sundays to gardens that supplemented their diets. The human body, in sum, needed rest and rejuvenation to pick cotton.41

Thus the dilemma for the masters was to increase production up to the absolute physical limits imposed by daylight, handwork, and fatigue. The masters tried physical force, but this, too, had natural limits. When they pushed the hours of work into the evening and Sunday, the slaves grew malnourished, weary, and slow. If they whipped the slaves, the physical pain they inflicted inspired resistance, perhaps flight. And eventually, violence broke down the human body, which contradicted the whip's instrumental purpose.42 The masters tried another tactic, premised not on force and punishment but on incentive—they began to pay premiums to slaves, often a penny per pound, for picking above a targeted daily minimum, and they began to pay the slaves to work on Sundays. Thus, in the midst of a brutal slave regime, something remarkable happened: the difficult, resistant natures of the cotton boll and the human body contributed to the formation of an incipient wage system characteristic of a “free labor” economy. In many places in the South during the early 1800s, a market developed for the Sunday labor of people who were slaves during the remainder of the week. Some masters, in fact, found themselves engaged in competition with each other for the services of their own laborers.43

Even as slaves profited from this economy, some growers were busy introducing, discovering, and breeding new cotton varieties that gradually altered the nature of the master-slave struggle. One of the greatest developments in the history of the Cotton Kingdom was the combination of accident and design that caused the spread of new cotton varieties across the South. In 1811, a fungal rot afflicted Mississippi Valley cotton fields, reducing yields of the Creole black seed variety by as much as 50 percent. The bolls on cotton plants grown from seed recently introduced from Mexico resisted the fungus. In subsequent years, pollinating insects cross-fertilized the Mexican, Creole, and Georgia varieties. These plants then generated new seeds that grew into a hybrid variety of impressive vigor and productivity. Not only did the hybrid “Mexican cotton” resist rot and produce more bolls per plant, but its bolls matured earlier and often simultaneously and, when ripe, opened much wider, enabling a laborer to pluck their fiber more easily. Over the years, systematic selection elaborated these traits into monster plants. An observer in Mississippi during the 1850s, for example, recorded 54 bolls growing on a bush two and one-half feet tall, and 134 bolls bursting from a plant of three feet. Such fecundity changed the nature of harvest labor. Whereas a top hand picked thirty to fifty pounds per day of Creole or Georgia cotton, he or she now picked two hundred or more pounds of the Mexicanized hybrid. By serendipity and selectivity, the masters had harnessed the botanical power of cotton to their agricultural ambitions.44

Mexican cotton's phenomenal organic productivity, however, did not necessarily give the masters greater power over their slaves. Although the plant required slaves to pick more pounds, those pounds offered the laborers important opportunities to retain or win autonomy from the masters. In South Carolina, for example, the productivity of Mexican cotton invited slaves to tend their own patches at night and on Sundays and to sell the small harvest for cash.45 More important, the abundant nature of the Mexican hybrid motivated masters to continue to pay premiums for pounds of cotton harvested above the prevailing standard. As fiber flooded the market and drove down prices, the masters tried to uphold their profits by growing and harvesting even more cotton.46 Just as they had offered incentives to slaves to pluck small quantities of Creole or Georgia cotton faster, so they now offered similar incentives to entice their laborers into collecting as much as possible of the massive surplus generated by the Mexicanized hybrid.

Here was a startling botanical paradox: a fixed number of field hands could cultivate more acres of Mexican cotton than it could harvest. The laborers could plow, sow, scrape, and hoe as many acres as they were physically able, but they could never work long or hard enough to pick all the fiber from those acres before spring arrived and they had to begin plowing and planting again. Thus, at picking time, masters still found themselves in the predicament of having to mobilize additional labor in order to maximize the harvest and their economic gain. They had three alternatives. They might pay a hefty fee to another master for the temporary use of additional hands. They might create their own labor reserve by purchasing more slaves, in which case they had to find work for those extra hands before and after the harvest. Or they might try to boost the efficiency and productivity of their existing slave force by paying premiums.47 Whenever they paid premiums, they revealed the power of the Mexicanized hybrid to alter the terms of the master-slave struggle.

The masters tried to win back a measure of the power they ceded. In particular, a national depression during the 1830s compelled some cotton growers to intensify their regimentation and control of their laborers. While some masters began marketing their slaves' Sunday cotton production, often for less than the highest price, others prohibited such production altogether. On some plantations, masters introduced credit and other forms of noncash incentives. Louis Hughes recalled that his owner organized field laborers into two teams for a cotton-picking competition. The winning team received a cup of sugar for each hand. “The slaves were just as interested in the races as if they were going to get a five dollar bill,” Hughes remarked. John Brown recalled that his master organized competitions “for an old hat, or something of the sort.”48 Still, the superabundance of Mexican cotton continued to encourage some masters to pay cash premiums. In 1849, one Alabama planter used the technique to entice his labor force to harvest an average of 350 pounds per hand every day for three weeks straight. Other planters retained the practice of cash wages for Sunday labor. “It is usual,” Solomon Northup said, “in the most hurrying time of cotton-picking, to require the same extra service.”49

Premiums or not, as fall turned to winter, the picking continued. Although the stalks had turned brown and brittle and the fiber inside the bolls dusty and yellow, the slaves still pulled their rough sacks down the rows. On Christmas day, rather than resting according to custom, some laborers—now momentarily, conditionally free—chose to pick cotton in exchange for cash. January arrived and then came February, and the pursuit of botanical wealth persisted. Across the lifeless landscape of the South, the thinly clad laborers toiled on.50

Soon, nature brought cotton production full circle. Lengthening days, moisture, and the promise of warmth signaled a new beginning to the cotton cycle, the awesome driver of southern history. Late one winter, while traveling through Louisiana, Frederick Law Olmsted paused at the edge of a Red River cotton field, perhaps in the vicinity of the Epps plantation and the sad little prison of Solomon Northup. As Olmsted looked on, the laborers “[broke] down, in preparation for re-ploughing the ground for the next crop, acres of cotton plants” on which “a tolerable crop of wool still hung, because it had been impossible to pick it.”51

FREE AT LAST

A magnificent botanical pulse of birth, growth, fruition, death, and decay, the crop cycle of cotton marked the passage of time across a good portion of the American South. There was another organic cycle that shaped the southern agricultural landscape as well, a cycle on which cotton depended but against which it also competed: the life cycle of enslaved people. Although cotton progressed from seed to fiber by means of cell division, respiration, photosynthesis, and other physiological processes, the plant still required human labor to survive. Without people to sow and till the crop, it would weaken and diminish and possibly perish. At the same time, the human body had physical needs that were not necessarily consistent with those of cotton. The human body required food, water, rest, nurture, and reproduction. Fulfilling those needs—bearing children, procuring food, recovering from fatigue, recuperating from illness, caring for the aged—took labor away from the cultivation of cotton. In short, the production and reproduction of the human body both supported and conflicted with the production and reproduction of the plant. The tension between the needs of the plant and the needs of the body shaped cotton culture in profound ways.

Solomon Northup's life and experience encapsulated the tension between cotton and the body. To get the wealth and power that cotton conferred, Edwin Epps needed Northup's body and its labor, but Northup could be included among the many organic obstacles that stood between Epps and his objective. Northup had no natural knack for picking cotton, nor had society disciplined his body from childhood to perform the task. His need for food and sleep absorbed energy and time, and microbial illnesses occasionally laid him low. His eating, sleeping body, moreover, supported an intelligent brain and a mysterious life force that people then and since have called the soul. Body, mind, and soul, one and inseparable, were the font of slave resistance, a perpetual challenge to the masters' power.52 Fiddling, a bodily activity for which Northup had great natural aptitude, focused his mind, soothed and inspired his soul, and opened opportunities for him to experience moments of liberty—moments at which he might even contemplate escape. Epps used physical force to counter the organic obstacle that Northup's body posed, but force undercut the slave's instrumental and economic value. Ultimately, in sustaining Northup, Epps sustained an obstacle to the accumulation of wealth in botanical form.

The tension between bodies and plants that shaped southern cotton culture began with the formation of children. Masters recognized early in the history of North American slavery that human fertility and “natural increase,” not just crop commodities, promised to enrich them. More slaves meant more hands to do more work, and more slaves meant more chattels that could be sold or rented to others. Yet the reproduction of slaves and cotton often conflicted.53

Some enslaved women resisted the masters' efforts to control and profit from their reproductive powers. Abstinence enabled them to postpone or prevent pregnancy. So did the prolongation of breastfeeding, which stimulated the release of hormones that delayed ovulation. Enslaved women also drew on African and New World pharmacological knowledge and ingested contraceptives or abortifacients such as calomel, turpentine, indigo, calamus root, and the root of the plant to which they yielded so much labor: cotton. One of the plant's evolutionary adaptations was gossypol, a toxic chemical compound that reduced the fertility of the herbivores that consumed it. The irony was as rich as river bottom soil: cotton's resistant nature enabled enslaved women to resist the reproduction of more children who would cultivate more cotton. “Maser [master] was going to raise him a lot more slaves,” Mary Gaffney later explained, “but still I cheated Maser[.] I never did have any slaves to grow and Maser he wondered what was the matter…. I kept cotton roots and chewed them all the time but I was careful not to let Maser know or catch me.”54

The nature of field labor intensified the rivalry between human and botanical reproduction. Slave owners needed women's labor and the labor (and commodity value) of the children the women bore. Long workdays, exhaustion, and poor nutrition, however, reduced the female laborers' ability to conceive, and once pregnant, the women experienced working conditions that threatened the security of their unborn children. Jepsey James demanded hard labor from the pregnant women on his Mississippi cotton farm. When one of them failed his expectations or resisted him, he confronted a problem: how to punish her—how to hurt her—while leaving untouched the valuable property in her womb. His solution was to order the woman to lie face down over a hole in the ground, her distended belly projecting into the cavity. With her unborn child thus shielded, James freely applied the lash.55

Even if the unborn escaped such violence unscathed, the contrary pulls of cotton cultivation and childbearing shaped children's prenatal and neonatal development. Pregnant field hands who received insufficient nourishment produced small, unhealthy babies; the average birth weight of an enslaved child in the American South may have been as low as five and one-half pounds, and many entered the world stillborn. Should an infant survive birth, his or her mother enjoyed momentary freedom from the most exhausting forms of work. Masters assigned nursing women, called sucklers, light tasks such as repairing fences and shucking corn or allowed them to hoe or pick less than the other hands. Easier duties allowed sucklers to breastfeed their infants several times a day. On some plantations, the master regimented even this limited freedom; each day at the appointed times, the overseer sounded his horn, calling the mothers to breastfeed their offspring. Regular breastfeeding strengthened the newborns. Kept in a nursery under the care of aged women or older children, placed at the side of a field, or slung across a mother's back, the infants held their own.56

Within a few months of delivery, the masters decided that cotton needed more attention and babies less, and they pressured nursing mothers to return to full-time field labor. Infants that breastfed less often lost the nutritional and immunological protections that mothers' milk provided. Antibodies in the milk no longer flowed regularly into their stomachs, but disease organisms did, from contaminated water, tainted cow's milk, and unsanitary utensils. The children were most vulnerable when the needs of cotton were most urgent—at the beginning of the crop cycle, when all hands were needed to sow, thin, and weed, and at the end, when the cotton needed to be picked. Mortality increased dramatically at those times, as cotton accumulated at the cost of children's lives. Infancy and early childhood were a grim struggle for many enslaved children. Fewer than half survived to age five, a mortality rate roughly double that of America's free population.57

After enslaved children reached the age of eight, their diet improved, their mortality declined, and their bodies began to grow normally. Not only were older children better able to fend for themselves and get the nourishment they needed, but their participation in fieldwork earned them more food, including meat.58 The maturation of children, however, did not completely reconcile the competing needs of bodies and plants.

To produce cotton, the masters and their slaves had to raise food crops and food animals. Corn was the most important source of plant food, and by the 1860s, the South devoted more acres to corn than to cotton. Corn offered important ecological, agricultural, and economic advantages to cotton producers. The plant grew well in the South's climate and soils and, when dried, stored well. Corn's crop cycle, moreover, was different enough from the crop cycle of cotton that the two did not always conflict. Corn was planted around March 1, “about a month earlier than the cotton,” recalled Louis Hughes. “It was, therefore, up and partially worked before the cotton was planted and fully tilled before the cotton was ready for cultivation.” Corn cultivation, moreover, had the potential to absorb surplus labor kept in reserve for the cotton harvest.59 Corn also made excellent feed for livestock, especially hogs, the South's greatest source of meat and fat. Hogs foraged for acorns and other nuts on unused land that southerners called the open range; masters and slaves later fattened the animals on corn.60

Despite their advantages, corn and hogs posed obstacles to cotton and its kingdom. One obstacle was agricultural. The crop cycles of corn and cotton were still close enough that slaves had to coordinate their cultivation of both plants carefully, maneuvering from one to the other in an effort to meet the needs of each. The diary of Levin Covington, a Mississippi planter, suggests the complexity and difficulty of the work. “All hands transplanting corn in No. 4 till breakfast,” wrote Covington in spring 1829, “then started 4 Ploughs throwing off from corn in old Sheep pasture, finished that & broke up middles in cotton part of same—Hoes finished transplanting and commenced after the ploughs to scrape corn at 12 o'clock, finished and scraped small piece of cotton the second time & stopped an hour by sun.”61

The other obstacle that corn and hogs posed was physiological: corn and pork—especially pork fat—were insufficient sources of human nourishment. Slaves normally received a weekly ration of corn and bacon. Each day they ground the corn into meal, mixed it with a little water, and formed it into cakes or fritters, often called hoecake or Johnnycake. Then they baked the cakes and dipped them in grease from the bacon or fried the fritters directly in the melted fat. On the Epps plantation, Solomon Northup consumed such fare. Sundays at the corncrib and smokehouse, he took possession of the coming week's food: enough corn to make a peck of meal (eight quarts, or two gallons) plus three and one-half pounds of bacon.62 Corn and bacon certainly could provide the calories that Northup and other enslaved people needed for strenuous labor, but they could not provide the nutrients necessary for a healthy diet. Many slaves thus suffered from diseases such as pellagra, caused by a deficiency of niacin, an essential B vitamin. Corn contained niacin in a chemical form that required the amino acid tryptophan to release it. Lean meat furnished the necessary tryptophan, but fat pork did not. Symptoms of the disease included body pains, scaly skin, reddish eyes, a coated tongue, headaches, dizziness, and, in its worst stages, diarrhea, hallucinations, stupor, and death.63

Charles Ball observed signs of malnutrition, perhaps pellagra, among slaves during the many years he labored in South Carolina and Georgia. “A half starved negro is a miserable looking creature,” he recalled. “His skin becomes dry, and appears to be sprinkled over with whitish husks, or scales; the glossiness of his face vanishes, his hair loses its colour, becomes dry, and when stricken with a rod, the dust flies from it.” John Brown remembered the symptoms of malnutrition in his own body. “In truth I was not much to look at,” he recalled of his humiliating sale on the auction block. “I was worn down by fatigue and poor living till my bones stuck up almost through my skin, and my hair was burnt to a brown red from exposure to the sun.”64

Slave masters strove to overcome the obstacles that corn and pork imposed, directly or indirectly, on cotton production. Depending on the season, some gave their slaves additional food, such as potatoes, cabbage, rice, peas, fish, molasses, and a little salt.65 John Brown told about the soup made of corn and potatoes—called loblolly, mush, or “stirt-about” (stirabout)—that the cooks dished out to the field hands, one pint per hand, for their noon meal. One day Brown's master added something else to the mix: cottonseed. Sheep and cattle consumed “oil cake” made from crushed surplus cottonseed, and perhaps a little of the same might suit the slaves. It was a logical idea, at least in the abstract, because feeding cottonseed to slaves would help reconcile the opposing pulls of cotton production and food procurement. In effect, it would allow the master to have his cotton and eat it, too. Brown ate the cottonseed as ordered, but the experiment backfired. The swill was “unwholesome,” he remembered, and “I broke out in great ulcers, from my ankle-bone upwards.”66

Unless they were willing to devote more time, labor, or money to the sustenance of slaves, the masters had but one solution to the deficiencies of corn and pork: allowing enslaved people the time, space, and resources to procure additional food. By tending their own gardens and livestock and by hunting, fishing, trapping, and gathering, slaves could supplement their cracked corn and greasy bacon. The alternatives, smaller quantities of cotton or run-down slaves, were unacceptable.67 But by allowing enslaved people to tend gardens, keep chickens, pursue wild game, and gather berries and nuts, the masters relinquished a measure of power and liberty to them. Slaves who engaged in their own provisioning enjoyed greater personal autonomy, accumulated small amounts of cash, strengthened their bodies, perfected survival skills, and gained access to spaces that enabled their attempts to escape.68

Gardens tended by enslaved people were some of the most important resources in the Cotton Kingdom. Near the slave quarters, on small plots of unused farmland or in the forests that surrounded the plantations and farms, the slaves tilled small patches, one per family or cabin, of onions, potatoes, cabbages, cucumbers, pumpkins, melons, peas, turnips, and other fare. The size, number, and location of the patches depended on the farm or plantation and the number of slaves who lived there. On the South Carolina cotton plantation where Charles Ball toiled, some 250 slaves tended about thirty gardens, most of them located “in some remote part of the estate, generally in the woods.” Bondmen such as Ball worked their gardens in the evening, at night (on some occasions to the light of torches held by children), and on Sundays. Not only did gardens provide nutritious food, but they also allowed the slaves to produce small surpluses, which they sold to masters and other free people. The cash permitted the slaves to purchase basic clothing, additional food, and small luxuries such as tobacco, candy, and alcohol.69

Livestock enabled enslaved people to put additional protein on their tables. Slaves kept chickens, ducks, geese, and turkeys around their own quarters, as well as hogs, horses, mules, and cattle, which foraged on the uncultivated land that stretched away from farms and plantations into unsettled areas—a vast open range encompassing more than 90 percent of the South's total acreage. The keeping of livestock connected enslaved southerners to a great regional herding tradition, and although they were not legally free, they nevertheless claimed their right to a common landscape.70

The open range also provided a diverse array of wild foods, which slaves collected at night and on Sundays. Uncultivated areas on and off the farms and plantations supplied nuts, berries, and greens. George Ball recalled eating a simple meal with his adopted slave family: cold cornbread and boiled leaves from lamb's-quarters, a plant common to North America and an excellent source of vitamin C, which was necessary for preventing scurvy. The South's immense commons teemed with animal life—deer, rabbits, opossums, raccoons, groundhogs (marmots), wild pigs, squirrels, turtles, fish, and other creatures—that provided extra protein. Some of the animals thrived in ecological relationship to food crops. Solomon Northup, for example, explained that the masters encouraged slaves to hunt raccoons, “because every marauding coon that is killed is so much saved from the standing corn.” Although meat from all the animals was nutritious and tasty, the slaves preferred some to others. “The flesh of the coon is palatable,” Northup pronounced, “but verily there is nothing in all butcherdom so delicious as a roasted ‘possum.”71

Enslaved southerners employed an impressive array of techniques and skills to capture their prey, some probably inherited from their African forebears. Masters generally prohibited the use of firearms, so slaves resorted to traps, snares, weirs, sticks, clubs, stones, bows and arrows, and, when necessary, their bare hands. Some methods required great cunning, inventiveness, and patience. Frederick Law Olmsted met a slave who had attached a scythe blade or butcher's knife to a wood staff, making a kind of lance. He positioned the lance “near a fence or fallen tree which obstructed a path in which the deer habitually ran, and the deer in leaping over the obstacle would leap directly on the knife. In this manner he had killed two deer the week before my visit.” Solomon Northup, skilled in carpentry as well as fiddling, fashioned an ingenious fish trap from short pieces of wooden board and sticks. Wet cornmeal and pieces of cotton rolled together and dried into hard lumps served as bait.72

Other hunting methods required extraordinary stealth. Charles Ball stepped softly along the edge of the South Carolina swamp. Spotting his prey, he stopped; slowly, carefully, he reached down—and snatched the turtle. Tying a strip of hickory bark around a flailing rear leg, he hung the animal from a nearby tree branch. After catching several turtles, he carried them back to his quarters and put them in a hole surrounded by a low fence made of split wood. Now and then he poured water into the hole to sustain his captives. When he was hungry, he pulled one out, butchered and cooked it, and enjoyed its meat.73

Perhaps the most important hunting method involved the use of dogs. Widespread throughout the South, dogs played crucial roles in the agroecology of the region. Masters used them for hunting foxes, deer, bears, game birds, and other wild creatures and for herding livestock, guarding family and property, catching rats, and, in the form of bloodhounds, pursuing runaway slaves. In “a world teeming with dogs,” as one historian has described the canine South, slaves easily acquired the animals and trained them to hunt. Masters had reason to tolerate if not encourage the practice, because it checked varmint populations and helped slaves augment meager rations. Charles Ball, one of the rare bondmen whose master allowed him to hunt with a gun, did so in the company of Trueman, his dog. Most slaves used dogs alone. Dogs flushed the prey, chased it, and treed it. Slaves then shook the tree and dislodged the prey or climbed up and knocked the animal from its perch. When it fell to the ground, the dogs clenched it in their jaws and shook it to death.74

The slaves' procurement of food nourished their bodies, enabled the production of cotton, and, in effect, strengthened the institution of slavery. Yet such self-sufficiency also posed problems for the masters. One problem was physiological and instrumental: slaves devoted so much effort at night and on Sundays to gardening, hunting, and other subsistence activities that they were too exhausted to be efficient field hands. Masters wanted slaves to feed themselves, but they did not want any reduction in the labor and energy expended on cotton.75 Even more problematic for the masters, slave self-sufficiency encouraged slave independence. Hunting with dogs allowed enslaved men to be manly producers who provided important sustenance for their families.76 Subsistence practices such as hunting also opened opportunities for slaves to resist the regime that dominated them, by helping them to steal from the masters and by allowing them to acquire knowledge and learn skills that enabled their attempts to escape.

A dog trained to hunt raccoons could also be used to hunt one of the master's hogs. The more forests, fields, thickets, ravines, wetlands, streams, and other subsistence environments a plantation encompassed, the harder it was for a master or overseer to detect such pilfering. A trained dog, moreover, could stand sentinel while a slave raided a smokehouse or other storage building.77 Similar circumstances abetted the slaves' theft of garden produce. If a hog belonging to a slave ate some of the master's corn or potatoes, how would the master know the damage had not been done by one of his own animals? If slaves kept gardens, how would the master know whether the slaves' reserves of corn, potatoes, or other fare came entirely from their own patches or partly from the master's fields and storehouses?78

Charles Ball's experience with fishing demonstrates the process by which self-provisioning and theft overlapped. Early one year, at the conclusion of the cotton harvest, Ball embarked on a scheme to use his knowledge of fishing to improve his standing with the master and escape the drudgery of field labor. When Ball caught some fish in his weir, he gave them to the master. Pleased and impressed, the master summoned Ball to the great house and discovered that the slave had learned to use a seine on the Patuxent River in Maryland. The master then ordered Ball to lead an expedition to the nearby Congaree River to catch fish for the entire plantation. With the assistance of a few other hands, Ball made some canoes, knit a seine with ropes and twine furnished by the master, and began hauling in fish from the slow, tepid, swampy stream. The master allowed Ball and his crew to eat all the catfish, pike, perch, mullet, and suckers they desired, but he forbade them to consume shad, the fattest and most flavorful of the fish. Shad, the master made clear, were to be reserved for him alone. To ensure the success of the project and to ensure that Ball and his fellow slaves turned over all the shad, the master appointed a white supervisor.79

Ball was disappointed at having to put up with the oversight of a “fish-master,” but he soon contrived a means to elude the man's gaze and steal some of the shad. Not only was the fish master ignorant of seine fishing, but he was also uninterested in working at night, the best time for taking shad. In Ball's view, the fish master “had not been trained to habits of industry, and could not bear the restraints of uniform labour.” By working hard and dutifully surrendering the shad, Ball and the other slaves convinced the man that he could trust them to work at night without supervision. Once alone, Ball and his co-workers ate some of the forbidden fish. Not only that, but they exchanged shad for bacon with traders who boated the Congaree by night. Ball's scheme almost fell apart when one of his co-workers, Nero, decided to use the cover of fishing and darkness to sell stolen cotton to a trader. When the plantation overseer arrived at the fish camp to investigate, he was startled by the plumpness—indeed, the very smell—of the slaves, the result of their rich diet. He could only scratch his head, curse, and wonder about the fatness of the fishermen while “the hands on the plantation were as lean as sand-hill cranes.”80

Slaves did not trouble themselves over the means by which they procured their food. They needed nourishment sufficient to perform the hard labor of bringing in the cotton, and whether they grew food for the masters to dole out to them, produced it by their own private efforts, or stole it mattered little to them. “If we did not steal,” explained John Brown, “we could scarcely live.”81 Slaves were eclectic producers and foragers, and the Cotton Kingdom in its totality constituted a vast environment of multiple possibilities for subsistence, including thievery.