1 | WILLIAM CLARK’S MAP

However our present interests may restrain us within our own limits, it is impossible not to look forward to distant times, when our rapid multiplication will expand itself beyond those limits, & cover the whole northern, if not the southern continent, with a people speaking the same language, governed in similar forms, & by similar laws; nor can we contemplate with satisfaction either blot or mixture on that surface.

—THOMAS JEFFERSON to James Monroe, November 24, 1801

IT IS A COMMONPLACE TODAY TO REFER TO ST. LOUIS AS THE “Gateway to the West.” But there was a time when the land that sits today in the shadow of the Gateway Arch was neither part of the West nor just east of the West, nor the gateway to anything. It was just the world—indeed, the center of the world. Of course, it was not St. Louis then either, but the ancient city of Cahokia, the metropolis of the Mississippian Mound Builders and the largest city in North America during the eleventh century. Cahokia was in what is known today as the American Bottom, on the east side of the river with satellites near what is today East St. Louis and across the river, on the west side, in St. Louis, known in the nineteenth century as the “Mound City.”1

Over the course of the nineteenth century, many of the mounds for which the city was known were deliberately leveled, so that streets could pass through, or bucketed out and used as backfill to support the rising foundation of the growing city. As many as forty-five mounds were dismantled in East St. Louis and another twenty-five or so in St. Louis in the years before the Civil War. Today only one mound remains in the city of St. Louis. Across the river, around the center of the once-great city of Cahokia, about fifty of the original approximately one hundred twenty mounds, some of them once forty or fifty feet high and hundreds of feet across, remain. Some of them rise out of the floodplain of the Mississippi River in uncanny echo of their ancient grandeur, and some are so worn away by erosion and foot traffic as to seem only small bumps in the otherwise level bottomland. They stand today as a weary reminder of the history before the empire that unfolded from St. Louis over the course of the nineteenth century, beginning in the century’s first decade with the upriver journey of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, an initial reconnaissance mission for a set of increasingly greedy and increasingly deadly military and economic forays launched from St. Louis.2

At its peak, Cahokia had a population of around ten thousand (larger than London at the same time) and a hinterland almost fifty miles in radius populated with another twenty thousand or thirty thousand people. It was connected by networks of travel and trade northward to present-day Minnesota and Wisconsin and southward to Louisiana, and possibly beyond to Mexico and Central America. The city consisted of as many as fifteen hundred structures, including one hundred earthen monuments, spread over thirty-two hundred acres. Some speculate that it grew suddenly, over the course of several years, as a sacred site spurred by the deep-space detonation of a supernova that brightened the skies around the globe in 1054. Cahokia was apparently laid out in advance of being inhabited. At its center was a massive plaza (sixteen hundred by nine hundred feet, about six times the size of Red Square in Moscow) headed by the largest of the mounds, the so-called Monks Mound—about one hundred feet high and almost nine hundred feet at the base, as broad as the pyramid at Giza and wider than the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacán in Mexico. Recent archaeological work suggests that the mounds were built out of blocks of cut sod, laid in alternating bands of light and dark, and pounded firm underneath the feet of the builders.3

Most of the mounds were leveled at the summit. Topped with buildings, they provided a platform for celestial observations—the entire city was laid out in observation of the movement of the sun, the moon, and the stars—and for sacred rituals. Cahokia seems to have been the site of tremendous festivals; one, archaeologists estimate, involved the simultaneous butchering and preparation of almost four thousand deer. The residents of the city lived in thousands of densely clustered thatched-roof houses, their floors dug down into the earth to keep them cooler in the summer. They made small clay sculptures and copper jewelry and chiseled arrowheads and knives out of river rocks.4

And then, for reasons that are lost to history, the Mound Builders seem to have walked away. Perhaps they had overhunted or overplanted their hinterland, maybe the city was riven by political conflict or social unrest, maybe they received the same type of celestial message that had caused them to move to Cahokia in the first place. Archaeologists speculate that, as the rulers of Cahokia gradually lost authority over their hinterland, their civilization dissolved into a welter of smaller polities and internecine wars. By around 1350, Cahokia was abandoned, the houses gone, and the mounds covered with grass, some of the largest falling in on themselves. The descendants of Cahokia spread across the plains and along the rivers, where they became the Arikara, the Hidatsa, and the Mandan, whom Lewis and Clark encountered on their way up the Missouri. For hundreds of years, the remains of what was once the largest city on the continent must have registered as only a distant reminder or even an eerie anachronism to the Indian hunters and traders who passed through the American Bottom.5

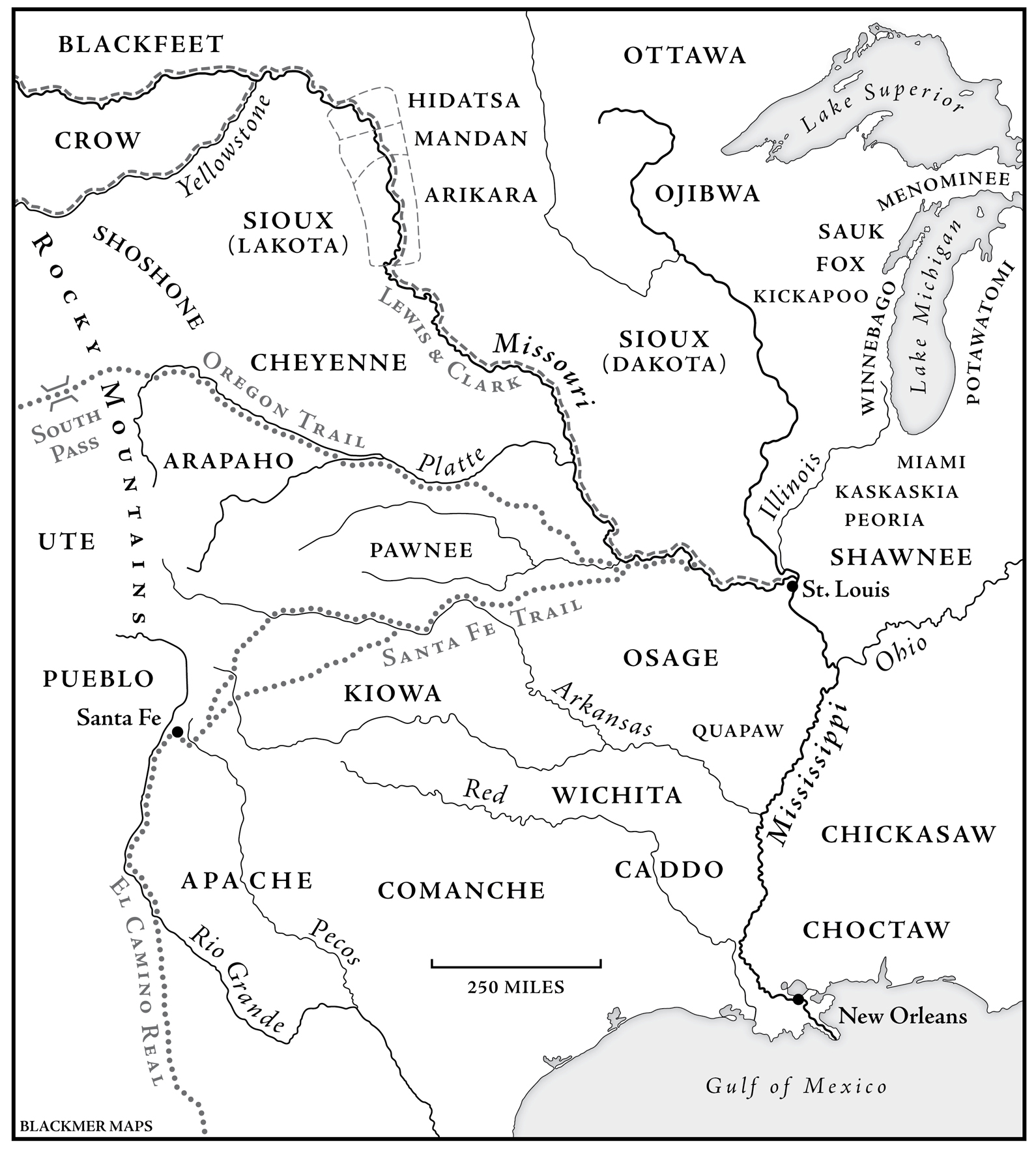

Missouri River Valley, c. 1803.

In February 1764, a small company of armed speculators led by Auguste Chouteau landed their boats on the west bank of the Mississippi River, across from Cahokia, and began to build a fort. They were employees of Pierre Laclède, a New Orleans trader, and they had traveled more than twelve hundred miles upriver to set up a trading post near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri—the first outpost in what became an empire in what became the West. They came to see the mounds around them as relics of an ancient civilization, one prior to that of the actual Indians in whose midst they had settled, and they concluded that the Indians, too, were interlopers, strangers in a strange land, and colonizers like themselves. They turned the mounds into a self-serving justification for empire.6

When Napoleon, sitting over four thousand miles away in Paris, sold the stake originally claimed by Chouteau to Thomas Jefferson in 1803, he did so without regard for the vast majority of the existing inhabitants of the Louisiana Territory—the nations of the Osage, the Mandan, the Arikara, the Sioux, and the Quapaw. Jefferson, of course, knew better. He was a student of Indians and of empire. He imagined the Louisiana Purchase as an “empire for liberty,” as a huge deposit of landed wealth upon which the future of white freedom might be based, but he did not think of the territory as empty. He knew that the Indians would have to be dealt with. In 1804, he sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to make a survey of the practical challenges and possibilities of empire-building in the West: to search out the long-rumored Northwest Passage to the Pacific; to catalog the flora and fauna; and to enumerate the Indians, announce to them the subordination of their nations to the United States of America, and gauge the economic potential of their lands. The expedition was carried out by a military reconnaissance force called the Corps of Discovery, a name that paradoxically and ideologically erased the people upon whose land they would be traveling and upon whose hospitality and knowledge they would depend—as if they were the first people to navigate the rivers and walk the paths about which they would learn from Indians. They left from St. Louis, which was at that time little more than an imperial outpost—a handful of buildings and warehouses along the riverbank with a population of around 1,200 people, most of whom were connected in one way or another with the fur trade. An 1805 visitor to the city referred to it as “cantonment St. Louis”—an isolated, surrounded, embattled outpost on the verge of a menacing future.7

The white men who carried the American flag and the news of conquest up the Missouri River knew better than even Jefferson that the lands through which they traveled were not simply sitting there like so much empty space on a map, waiting to be discovered. They were soldiers and frontier traders, men who were accustomed to seeing the land over which they traveled as contested ground—as a patchwork of claims and counterclaims and a place thick with possible allies and potential enemies. More than as explorers, we should see them as special forces—a military reconnaissance operation operating well beyond the line of effective US control, empowered to make friends among the Indians wherever they could find them, but enjoined always to remember that they were operating in hostile territory.

Meriwether Lewis was born in 1774 to a settler family in Georgia in the midst of a long-running, medium-intensity war with the Cherokee. As a young man, he moved to Virginia, where he became a leader in the new state’s militia—a force created to maintain sovereign order among the slaves, the Indians, and even insurrectionary whites—and where he caught the attention of Thomas Jefferson. After the Corps of Discovery returned to St. Louis in 1806, Jefferson appointed Lewis military governor of the Louisiana Territory, but plagued by drink, the famous explorer was dead by 1809, shot to death in a Tennessee roadhouse, whether or not by his own hand no one has ever finally established.8

Born in Virginia in 1770, William Clark was the younger brother of the Revolutionary War hero and famous Indian killer George Rogers Clark. He too was a Jefferson protégé; though not as fluent a writer as Lewis, he was a talented cartographer. Everywhere he stopped during his travels across the western half of the North American continent—at night in campsites on the banks of the Missouri; during the snowed-in winter of 1804 at Fort Mandan; near the nineteenth-century Indian villages of Mitutanka and Ruptare and present-day Bismarck, North Dakota; over the course of the miserable, starving, icy winter that followed at Fort Clatsop, near the Pacific coast—Clark recorded the information and observations he would use to entirely recast the geographic knowledge of the day: knowledge in the service of empire. William Clark’s map was arguably the most important and most enduring artifact of the Corps of Discovery’s reconnaissance mission: it was both imperial in its ambition to codify and control and ambivalent in its incompleteness and dependence upon Indian knowledge. It was a map of imperial ambition produced by a man who would not have survived his first winter (still less the other winters of the journey) without the help of the Indians over whom the president of the United States would soon give him sovereign dominion. For many years to come, and in many places, that dominion would be nothing more than science fiction waiting to be redeemed in blood. Over the next three decades, Clark would preside over several interlinked dimensions of the US imperial and Indian policy: the removal of most of the Indians who remained on the eastern side of the Mississippi River at the time of the Louisiana Purchase; the negotiation of removal treaties with the Indians of Missouri (among whom were some of his closest allies in the War of 1812) and surrounding territories; and the military reconnaissance, imperial regulation, and eventual invasion of the Missouri Valley. Apart from Andrew Jackson, it would be hard to argue that any white man had a greater influence on the US Indian policy in the first half of the nineteenth century than William Clark.9

As well as pen and ink, the men of the Corps of Discovery carried with them fifteen rifles issued by the US Army, several sidearms of their own, and a rare repeating rifle that belonged to Lewis and could fire as many as twenty shots in succession without reloading. They also had a cannon mounted on a swivel on the bow of one of their boats and two large, smooth-bored guns on the others. As they traveled upriver in the fall of 1804, they failed to observe frontier protocol by paying a toll to pass through Lakota territory near the big bend of the Missouri. When they were waylaid by the Indians, Lewis and Clark refused to negotiate, took the Lakota headman Black Buffalo hostage, and held him until they had passed out of Lakota territory. The Lakota, Clark recorded in his journal, were “the vilest miscreants of the savage race, and… the pirates of the Missouri,” an assessment that proved to be both foundational to the subsequent history of white settler attitudes toward the Lakota and monumentally ironic in light of the kidnapping and the events of the next two centuries.10

The Corps of Discovery spent its first winter on the Missouri at Fort Mandan—later renamed Fort Clark—a small stockade built near Mandan villages where as many as fifteen hundred people lived within and outside the walls. For the Mandans, the arrival of the Corps of Discovery was a peculiar, if not unprecedented, event. The Mandans had a history of trade with Europeans that dated to the seventeenth century; their most recent and frequent contact was with British traders who traveled down from Hudson’s Bay. As discordant as the assertion of white sovereignty may have seemed when delivered by a ragtag band of fifty men to a powerful settlement with four or five hundred soldiers, the Mandans were especially puzzled and irritated by the Americans’ refusal to trade with them. Indian diplomacy on the Great Plains depended upon an ethos of openhanded generosity and reciprocity. The hospitality shown by the Mandans was neither naive nor altruistic—it was their half of a relationship of the exchange portended, they assumed, by the expedition’s heavy-laden keelboat. But the white men of Fort Mandan seemed unusually stingy; they were obsessed with storing up their goods for other winters and other Indians farther up the river. When they tried to over-awe the Indians by firing off their cannon, they seemed to prefer “throwing [their ammunition] away idly rather than sparing a shot of it to a poor Mandane,” in words attributed to one of the Indians. Only when the expedition’s blacksmith finished setting up shop did the Corps of Discovery have something to give in return. “If we eat, you Shall eat,” the Mandan leader Sheheke promised the whites.11

For the Mandans, the arrival of Lewis and Clark was an odd but by no means unprecedented event: they were familiar with white men and commercial prospectors, especially fur traders. Their main concerns about the future involved their relations with their Indian neighbors, especially the Arikara to the south and the Sioux to the west. Lewis and Clark, by contrast, believed that they were on a pathbreaking mission and had limitless confidence in their ability to find and claim new territory, even believing that they were destined to do so. But they also knew that by the time they had reached the Mandan villages they had also reached the outer limits of their maps. There were European trappers and traders who lived in and traveled the Missouri River Valley, but they navigated according to memory and word of mouth. Based on the information they gleaned from these sources and on their incomplete and speculative maps (some of which were indeed more fanciful than speculative), Lewis and Clark had set out for the Pacific working on the hypothesis that the western half of the continent was a straight-up mirror image of the world east of the Mississippi.12

Over the course of the winter, the Mandans and their visitors provided Lewis and Clark with the maps that would guide the Corps of Discovery to the front range of the Rockies and beyond. They were initially drawn out on the packed dirt floors of Mandan lodges and then translated into notes and maps in Clark’s journal. When the American expeditionary force set out for the Pacific in the spring of 1805, the landmarks they sought and the decisions they made were based “altogether,” in Lewis’s words, on “Indian information… obtained on this subject, in the course of the winter, from a number of individuals, questioned separately and at different times.” After the winter of 1804, every single critical decision Lewis and Clark made was based upon what they had learned from Indians. After spring had turned to summer, months later and hundreds of miles upriver, Lewis and Clark faced what the historians have identified as the defining moment in the expedition. At a seeming fork in the Missouri River, a difference of opinion about which way to proceed threatened to grow into a violent conflict between the expedition’s leaders and their men—a backcountry mutiny that would surely have cost Lewis and Clark their lives. The embattled officers resolved the argument and settled on the south fork only after sending out an exploratory party in search of the landscape they had been told by the Mandans to expect. As Clark put it, “The [buffaloes] and the Indians always have the best route.”13

It was also at Fort Mandan, in the winter of 1804–1805, that Lewis and Clark met Sacagawea. Soon after the Corps of Discovery landed at the Mandan villages, a French fur trader named Toussaint Charbonneau and two Indian women arrived for the winter. No one knows when or how exactly Charbonneau had met either of the women with whom he traveled and whom he called his “wives,” but Clark believed that their relationship with him was something more akin to enslavement than marriage. Having grown up Shoshone in present-day Idaho, the women had been captured and enslaved by the Hidatsa, who lived on the Great Plains, upriver from the Mandans, toward the mountains. Women like Sacagawea and Otter Woman were trafficked—like furs, beads, horses, and guns—among European traders and those who trucked with them. Because property on the plains was passed matrilineally from generation to generation, marrying—buying, taking, raping—Indian women was a primary mode of both sexual and capital accumulation for Europeans.14

What Lewis and Clark took from Sacagawea was knowledge. This appropriation, too, was in accordance with the standard operating procedures of Indian slavery on the plains, where far-flung geographies of trade and the diversity of languages made those who could point the way across the landscape and translate among its inhabitants valuable. Indeed, it was in anticipation of their need for translators that Lewis and Clark engaged Charbonneau, who spoke Hidatsa, and his Shoshone wives. Otter Woman, who was seven months pregnant when the expeditionary force set out in the spring of 1805, stayed with the Mandans. Sacagawea went along with Charbonneau, carrying with her the couple’s two-month-old son, whom they had christened Jean-Baptiste.15

Sacagawea’s story bears repeating: it is as amazing as it is familiar. Carrying her son, she walked overland with William Clark and taught him about the flora and fauna of the Missouri Valley. She plunged into the freezing Missouri to rescue the expedition’s journals and maps when one of the expedition’s pirogues overturned on launching. (Charbonneau, who could not swim, had to be dragged out of the water along with the baggage.) She recognized the meadow where she had been captured, pointed the way to the Shoshone, and then astonished the Corps of Discovery as she rushed forward to embrace the leader of the Shoshone party, who had ridden out to meet the white travelers. He was, they soon learned, her brother. And shortly before the expedition started eastward to return to St. Louis, she insisted on riding out from the winter camping ground at Fort Clatsop so that she could see the Pacific Ocean with her own eyes.16

And yet, alongside the anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-better terms in which her story has been assimilated into the mainstream of American history, Sacagawea’s years with the Corps of Discovery also provide a set of data points that convey the unstable hierarchies and violent intimacies that shaped life between the borders of worlds. In August 1805, Sacagawea was beaten in camp by her husband, who was then publicly reprimanded by Clark. Clark may have felt protective, possessive even, of Sacagawea, whom he referred to as Janey. His affection for Jean-Baptiste was openly proprietary. His habit of calling the boy Pompey reflected not only the affection of a pet name but also southern slaveholders’ habit of amusing themselves by bestowing names drawn from the classical world upon their property. By the time the expedition returned to St. Louis, Clark wrote to Charbonneau and Sacagawea asking them to send the little boy to live with him. “Anxious expectations of seeing my little dancing boy Baptiest” led Clark to promise Charbonneau a fully furnished farm, if only the woodsman would “leave your little Son Pomp with me.” Jean-Baptiste was educated at Clark’s expense after his parents returned to the Hidatsas in 1809. He graduated from what is today St. Louis University High School as a member of one of the first classes after its 1808 foundation.17

Historians know Sacagawea, this most famous of Indian women, mostly through the words and deeds of the men who controlled and exploited her, and finally dispossessed her of both her property and her progeny.

In the years immediately following his return to St. Louis, William Clark continued to work on his map. Appointed superintendent of Indian affairs for the Louisiana Territory by Thomas Jefferson in 1807 (the office overseeing the United States’ Indian relations, and Indian wars, remained in St. Louis through the 1840s), Clark was responsible for licensing white explorers, traders, and trappers who planned to travel beyond St. Louis into Indian country. His office stood near the levee in downtown St. Louis, on a lot paid for by selling one of his family’s slaves. William Clark’s office became the epicenter for the expansion of the United States: the literal gateway to the empire, the trailhead of the pathways along which white men were converting Indian country into the West and existing trade networks and animal skins into capital. White men heading west stopped in to get their licenses and to look at Clark’s map before setting out. White men returning from the West brought with them their own observations and manuscript maps, which Clark incorporated into the master map he kept in his office. More than any published map, the map in Clark’s office provided an up-to-the-minute account of imperial knowledge during these years.18

The map itself captured the transformation of empirical into abstract knowledge—the conversion of the immediate, three-dimensional knowledge one gains from walking down a path into reproducible knowledge that can be communicated in two dimensions on a printed page. Upon its publication in 1814, Clark’s map would enable viewers in Washington or New York or St. Louis to imagine a western itinerary in the comfort of their own offices or sitting rooms. With Clark’s map, they could trace with a fingertip the course of the Missouri past the Mandan villages and into the mountains; imagine portaging across and following the downward course of the Columbia River toward the Pacific; foresee the day when the arduous journey from St. Louis to Santa Fe would be easy; or divine the purpose of God as it had been encoded in the geography of the continent. Moreover, Clark’s manuscript map provided an embedded record of the circumstances of its own creation—the rough, material, empirical process by which this imperial knowledge was created: “Mandan Village, 1500”; “The wintering fort of the party sent out by the government of the U.S. for discovery in the winter of 1804–5”; “Here was found the first Ogalala”; and so on. A final version of the map, stripped of the traces of its own creation, was finally published in 1814, along with the journals of the expedition. Clark’s manuscript map today hangs framed in the Beinecke Library at Yale University, a documentary record of the expropriation of Indian knowledge along the westward course of empire—of the translation of knowledge about the land from one kind of vision to another.