2 | WAR TO THE ROPE

Armed occupation was the true way of settling a conquered country. The children of Israel entered the promised land with implements of husbandry in one hand and the weapons of war in the other.

—THOMAS HART BENTON, “On the Armed Occupation of Florida”

AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF WHITE MEN WHO ARRIVED IN ST. Louis in the years after the War of 1812 was one who would later become one of the most famous imperialists of the nineteenth century. This man envisioned the transcontinental railroad decades before the first rail was laid; proposed simply giving away large portions of the West to white men; came to view the conflict over slavery as a distraction from the real business of empire; and considered dead Indians simply an afterthought, an acceptable cost of doing business in the West. Under the stewardship of Thomas Hart Benton, the western empire of the United States took shape. In the second quarter of the nineteenth century, St. Louis became the military headquarters of the Western Department of the US Army and the staging post for the Indian wars. White settlers—backed by that St. Louis–based US Army but often operating well in advance of its lines—violently removed Native Americans from lands all over the Upper Midwest. During Benton’s career, we can see the process by which genocidal settler wars replaced the volatile reciprocity of the fur trade world and then finally became the (made in St. Louis) official policy of the United States in the West.

In later years, Benton would be known for his speeches. For hours at a time, he would pound out one well-turned phrase after another. Whether he was on the floor of the US Senate or on a stump at some backwoods crossroads in central Missouri, he always sounded the same—like an angry god in love with the sound of his own voice. Benton would become one of the most renowned orators of an age that cherished words and admired speech, and the acknowledged equal (and persistent antagonist) of Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. But in 1815, Benton’s only claim to fame was among those who thought him a thief, a liar, and a bully. Like so many others, he had come to Missouri as a wounded white man seeking a second chance. As a young man, he had been expelled from the University of North Carolina for pulling a gun in an argument with a school-aged child and repeatedly stealing money from his roommates’ trunks. Disgraced, he had moved with his widowed mother across the mountains to Nashville, where he trained in law. He was finally beginning to establish himself when he was drawn into an affair of honor that would pit him against General Andrew Jackson, the city’s most prominent citizen who would soon become the nation’s most prominent Indian hater, and soon enough after that its tenth president.1

The cause of Benton’s famous fight with Jackson was both obscure and stupid—a series of slights passed between the aggrieved parties like a bad debt. The first act culminated with a duel between Benton’s brother, Jesse, and a military subordinate and friend of Jackson’s named William Carroll. Jackson was Carroll’s second, which meant it fell to him to arrange the dueling conditions on behalf of the challenged party. Jackson secured an agreement to duel with pistols under mortally dangerous conditions: the men would stand back to back only ten feet apart, then turn and fire simultaneously. When Jesse Benton shot first and missed, he sensibly and even instinctively—that is to say dishonorably—turned his back and tried to curl himself into a smaller target for Carroll, who cold-bloodedly—that is to say honorably—shot him in the seat of his pants.2

The short distance later seemed to Thomas Hart Benton to have unjustly favored Carroll, a notoriously bad shot. In the weeks that followed, Benton shared his unfavorable evaluation of Jackson, Carroll, and the circumstances of the duel far and wide. Jackson sent Benton a note requesting an explanation. Benton replied that he believed that Jackson had failed to forestall a potentially fatal encounter between overheated young men, and that he would not be cowed into keeping the general’s name out of his mouth. Jackson responded that he would “horsewhip” Benton the next time he saw him in the street, and on September 4, 1813, he attempted to do just that when he, along with two friends, encountered the Benton brothers in the Talbot Hotel in Nashville. As Jackson advanced, whip in hand, Benton reached for the pistol in his belt. But Jackson was faster, and he began, gun drawn, to back Benton down the hall of the hotel. Coming in from behind Jackson, Jesse Benton shot the general in the back, shattering his left shoulder, just as Jackson let loose an errant shot at Thomas Hart Benton. Jackson’s friends then set upon Benton with knives, stabbing him in five places before he was saved by tumbling down the back stairs of the hotel. As Jackson’s friends carried the grievously wounded general away to safety, Benton staggered, bloodied, into the street and broke Jackson’s sword over his knee.3

Although he may not have realized it at that moment, Benton was done in Nashville. After brief and undistinguished service in the War of 1812 under Jackson’s command—the general kept Benton away from most of the military action the younger man would have needed in order to enhance his reputation—Thomas Hart Benton decided to move to Missouri.

St. Louis in 1815 was an outpost at the beginning of a furious transformation: from the westernmost hub of the fur trade to the eastern hub of the nation’s settler empire. Over the first decades of the nineteenth century, the fur trade produced income that was invested in the city fabric of St. Louis, and the city grew from a few square blocks on Pierre Laclède’s landing, southward along the banks of the Mississippi toward Carondelet, westward to St. Charles, and northward to St. Ferdinand (today’s Florissant). In 1820, the city was designated the western terminus of the National Road, which was to connect the Mississippi Valley to the Potomac River and the East Coast. The scattered log cabins of the fur trade world would soon give way to a grubby host of riverfront warehouses and small manufactories—brickyards, tanneries, and smelters. The Chouteaus’ stone mansion, which had once stood apart from the city (close by today’s Busch Stadium), was gradually surrounded by it. By 1840, the city’s propertied leaders were surveying and selling off the commons that had once served to graze the city residents’ stock—it had become too valuable to leave as open land. By that time, the mixed population of trappers and traders—French, Indian, Negro—had long since been transformed into a populace organized by the rigid forms of racial hierarchy and white supremacy that prevailed farther to the east and that the city of St. Louis would play a key role in transmitting to the West. In 1810, the population of the city was less than fifteen hundred; by 1840, it had grown more than twentyfold, to around thirty-five thousand, with westering white men like Benton making up the bulk of the increase.4

Benton found work in the law office of Charles Gratiot, a Chouteau in-law whose primary business was turning territory into property—the legal aspect of settler colonialism. As the Chouteaus and the rival Lucas family surveyed, staked, and claimed the area that would become downtown St. Louis (the area to the west of Third Street), Benton worked on what would become a career-making case: the registration under US law of Spanish land titles held by the city’s Creole elite. (The Louisiana Territory had been under Spanish control from 1763 to 1803, when it was transferred back to France, only to be sold to the United States.) The Chouteau family alone had almost two hundred thousand acres of disputed property, bought up at bargain prices from risk-averse titleholders, and the Chouteaus stood to make a killing if they could establish clear title before the claims commission first established by Thomas Jefferson in 1805.5

Benton’s work in Gratiot’s office thus put him in touch with the first family of the city of St. Louis, whom he faithfully served up to his election to the US Senate in 1821, and indeed, ever after. His first speech in the Senate was delivered on behalf of the Creole speculators who had sent him there to do their bidding. And as the business interests of the city’s leading families gradually turned from the fur trade to Indian removal—that is, from using Indian labor to control resource extraction to using the control of Indians to extract revenue from the government—Benton was there every step of the way. In 1822, he termed the government-controlled trading factories in Indian country a “pious monster” and sponsored a bill that abolished them, effectively taking Indian trade out of the hands of the US Indian Agency and placing it in the hands of the American Fur Company and a seemingly endless supply of settler competitors. In 1825, Benton shepherded an Osage removal treaty through the Senate that included the direct transfer of hundreds of thousands of acres to the Chouteau family in repayment for Osage debts supposedly incurred at the family’s company stores; in 1851 he did the same in relation to a Sioux treaty that had been arranged by the American Fur Company agent J. A. Sanford. As the fur trade world gave way to settler colonialism and land speculation in the Midwest and the Great Plains, Benton helped his St. Louis patrons make the transition. “Senator Benton seems to have been as much an employee of Chouteau and Company as a representative of the people of Missouri,” one historian has mordantly observed.6

And yet it is as a champion of the people rather than as a corporate tool that Benton was known in the nineteenth century. Certainly Benton owed part of his populist persona to his reputation as a duelist, which he built on shortly after moving to St. Louis by killing the fur trade scion Charles Lucas on Bloody Island. The cause was once again both trivial and stupid—an argument in court between two lawyers that involved an escalating exchange of uses of the word “puppy.” His reputation as a duelist certainly helped his populist reputation, but Benton owed his status as the officially recognized voice of “the West” mainly to his vision of federal land, to the liberality he proposed in distributing lands taken from Native Americans to migratory white men like himself. Though it might seem ironic at first glance that a man who had gone to Washington as the Chouteaus’ prize pig, trussed up for sale to the highest bidder, made his reputation in the Senate as a stubborn and tireless advocate of the common man, there is actually no irony in it at all. Thomas Hart Benton was the type of populist fixer beloved by plutocrats throughout American history. Turning the attention of ambitious but impoverished white men like himself away from the ruling class as they sought an explanation for why rich men had so much when they had so little, he pointed them instead to the West: toward Indian lands and Indian wars. For Benton, Indian lands and empire (rather than class politics or revolution) held the promise of white equality.7

Benton’s signature issue was the Graduation Bill, which proposed the distribution of unsold federal lands at prices that declined twenty-five cents an acre every year until the entire public domain of the United States was privately owned. What could not be sold in the end should simply be given away. Thus would the West be whitened and cemented to the United States. “The tenant has, in fact, no country, no hearth, no domestic altar, no household god,” Benton famously declared, transforming the class conflict between white renters and landlords into a call for westering imperialism. “The freeholder, on the contrary, is the natural supporter of a free government.… I say give, without price, to those who are not able to pay.… It brings a price above rubies—a race of virtuous and independent farmers, the true supporters of their country.” Benton’s scheme was, at once, a spatial fix for class conflict in the East, a conversion of expropriated Indian lands into a subsidy for whiteness, a privatization of the public domain, and an effort to expand the imperial domain of the United States. It identified the national interest with the endless serial reproduction of white family farms as far as the sovereign power of the United States could reach, which, by the final time Benton went through the annual ritual of calling for graduation in 1854, was all the way to the West Coast. Benton’s graduation speeches were printed throughout the West, and his admiring supporters “had the terms of it by heart,” in the words of another senator. “They called their counties after him; they called their towns after him; they gave his name to their children; and it had secured to him an influence which nothing else could have obtained for him.”8

Though Benton was never successful in convincing his fellow senators to simply give away the public domain (that would have to wait for Abraham Lincoln), he did convince them to allow white settlers to pay bottom dollar. Following the provisions of the Indian Intercourse Act (1790), and according to the decision of the US Supreme Court in Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823), it was illegal for Indians to sell land directly to whites. Indian lands could only be transferred—by treaty or by sale—directly to the United States of America, whose General Land Office then surveyed and sold them at auction. All of the surveying, sale scheduling, and auctioning took time, however—time that restless and entitled white settlers resented and refused to endure. Long before the sales, white settlers from Georgia to Illinois simply moved onto Indian lands and started to farm them. In some cases, they literally drove people out of their own houses and moved in; on occasion they harvested fall crops that had been planted by Indian farmers that spring. Settler colonialism prevailed in the shadow of empire.

The problem was that the settlers were operating outside the effective administrative reach of the government upon which their claim to the land legally and practically—and militarily, in the final instance—depended. It was only the federal government that could legalize their land claims, but the government simply did not have time to survey all of the Indian lands it had taken. The solution was preemption. In 1830, along with his fellow Missouri senator David Barton, Benton sponsored a bill that gave white settlers who built a house and improved the land around it a preemptive claim on any 160-acre quarter-section eventually laid over their homestead by the General Land Office’s surveyors. That claim allowed them to purchase the land at the federally stipulated minimum price of $1.25 an acre before it was put up for auction—indeed, it allowed them to delay the auction of the land for two years while they farmed it in order to raise the money they would need to purchase it.

Administratively speaking, the policy was a disaster. It took the surveyor’s abstract grid on the maps in the Land Office and scrawled across them a chaotic social history of existing settlement, partial payment, and fraudulent claims of precedence. But politically speaking, it made Benton a hero not only in the West but among the emergent Jacksonian coalition of western farmers and eastern laborers. “The manufacturers want poor people to do the work for smaller wages; these poor people wish to go to the West and get land; to have their own fields, orchards, gardens, and meadows—their own cribs, barns, and dairies; and to start their children on a theatre where they can contend with equal chances with other people’s children for the honors and dignities of the country,” Benton intoned. Philosophically speaking, the policy of preemptive claims represented the elevation of settler colonialism to a principle of federal governance.9

Benton, promoter of preemption, thus made peace with the prime mover of Indian removal, Andrew Jackson, on the basis of their shared imperial ambitions for the nation’s common whites. After an elaborate series of deferential gestures involving the scheduling of meetings, pleasant inquiries about the health of one another’s wives, and an exchange of home visits, the old antagonists had established a working relationship during Jackson’s years in the US Senate. With Jackson’s election to the presidency in 1828 on a platform of “Indian removal today, Indian removal tomorrow, Indian removal forever,” Benton became one of his ablest allies and staunchest defenders in the halls of Congress. In Jackson, Benton found an ally willing to further the course of empire by any means necessary—and then some.10

From the beginning of his political career, Benton’s imperial ambition was scaled to the size of the globe. In 1819, while the United States was negotiating with Spain about the future of Florida, Benton was already writing an article in the Missouri Enquirer suggesting the further acquisition of Cuba, support for the independence of Mexico, and the development of trade routes to the Pacific and beyond.

The disposition which “the children of Adam” have always shown to “follow the sun” has never discovered herself more strongly than at present.… In a few years the Rocky Mountains will be passed, and “the children of Adam” will have completed the circumambulation of the globe, by marching to the west they arrive at the Pacific Ocean, in sight of the eastern shore of Asia in which their first parents were originally planted. The Van of the Caucasians and the rear of the Mongolians must intermix. They must talk together, and trade together, and marry together.

This passage, in its unwavering focus on the age-old dream of Pacific empire, its grandiloquence, and its racial and sexual entitlement was emblematic of the man. The serial restatement, revision, and practical application of this set of ideas consumed Benton for the thirty years of his career in the Senate, and even afterward, until his death in 1858.11

Benton’s unwavering focus on the West isolated him from the leading men of the Senate during much of his time in Washington. He was a vigorous opponent of the tariffs promoted by John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay, which would subsidize eastern manufacturers at the expense of western consumers and, more important to Benton, provide the federal government with a revenue stream other than from wholesale liquidation of the public domain: the Indian lands he wanted to make sure were sold off to the common (read: white) man. As the issue of slavery moved to the center of federal politics, Benton clashed repeatedly with both committed opponents of the institution, like Daniel Webster, and its most ardent proponents, like John C. Calhoun. Benton was a slaveholder, but for him the politics of slavery was simply a distraction from the business of developing the West; indeed, it was in empire that the conflict over slavery could be resolved, as expansion abroad would inevitably have “the effect at home of producing a more perfect fusion of the different elements composing our own National Union.”12

Benton was not so much the architect of the US Pacific empire as he was its prophet. In 1822, Benton proposed the creation of a military line of control along the spine of the Rocky Mountains, a set of forts in lands that were then in Mexico, to ensure American domination of the Indian trade as well as the Pacific trade he expected to emerge in the wake of the fur trade. During his time in the Senate, Benton sponsored four western expeditions, each of which departed from St. Louis to survey a route through Alta California (that is, Mexico) to San Francisco, the presumptive wellspring of the western empire, and each of which was led by the senator’s son-in-law John C. Frémont, “the Pathfinder.” Frémont’s expeditions of 1842 and 1843–1845 surveyed the Oregon Trail with the goal of providing a pathway for the wealth of Asia to make its way to the heart of the continent—St. Louis itself. In 1845–1846 and, finally, over the winter of 1853–1854 (by which time the United States had seized Alta California in the war with Mexico between 1846 and 1848), he traveled across the Rockies, seeking a gap that might allow the building of a transcontinental railroad along the thirty-eighth parallel, from St. Louis to San Francisco.13

It was in support of that railroad that Benton gave what is perhaps his best-remembered speech, at a railroad convention held in the Mercantile Library in downtown St. Louis in October 1849. The transcontinental railroad, Benton intoned, would be a “Western route to Asia.” And from empire in the Pacific and the exchange of goods, Benton imagined, would follow the progress of civilization:

The furs of the north, the drugs and spices of the south, the teas, silks and crapes of China [silk fabrics, or “crêpe de chine”], the Cashmeres of Thibet, the diamonds of India and Borneo, the various products of the Japan Islands, Manchooria, Australasia, and Polynesia, the results of the whale fishery, the gold, silver, quicksilver, jewels, and precious stones of California.… Our surplus… products would find a new… market in return, while the Bible, the Printing Press, the Ballot Box, and the Steam Engine, would receive a welcome passage into vast and unregenerated fields, where their magic powers and blessed influences are greatly needed.

Benton outlined a history of the future, of the American Dream of a Pacific empire, that reverberated through the late nineteenth century and even beyond. Seen in this light, it is unsurprising that Benton’s first and most admiring biographer was the man who is credited with bringing so many of the Missourian’s imperial dreams into martial being: Theodore Roosevelt.14

But not even the Seer of St. Louis, the prophet of Pacific empire, could foretell the future with perfect accuracy. Benton topped off his speech to the railroad convention with a brighter vision of the future of St. Louis (well, of the whole world, really) than he would be able to provide in reality. “Three and a half centuries ago,” he concluded, ending at what he thought of as the beginning of the history he was trying to make,

the great Columbus… departed from Europe to arrive in the East by going to the West. It was a sublime conception.… It lies in the hands of a Republic to complete it.… Let us rise to the grandeur of the occasion. Let us complete the grand design of Columbus by putting Europe and Asia into communication… through the heart of our country.… Let us beseech the National Legislature to build the great road upon the great national line which unites Europe and Asia—San Francisco at one end, St. Louis in the middle, New York at the other; and which shall be adorned with its crowning honor—the colossal statue of the great Columbus.

Benton is today memorialized in St. Louis’s Lafayette Park with a statue carved by Harriet Hosmer in 1861 in the way he had imagined Columbus: clad in the toga of a Roman senator over his suit and shod in the heavy boots of a nineteenth-century explorer, gazing westward, above the inscription THERE IS THE EAST. THERE IS INDIA—the most famous line of the railroad convention speech.15

Of the actual Indians who lived along the route of Benton’s railroad, or the Indians he commonly saw on the street in St. Louis and considered during his years on the Senate committees on military and Indian affairs, Benton said very little. Of the Shawnee, the Delaware, and the Osage in Missouri, he wrote with none of his accustomed grandiloquence, but rather with a succinct and implacable savagery more often associated with Andrew Jackson: “Sooner or later they must go.” Where many whites, including imperialist whites, continued to support the Jeffersonian notion of the Louisiana Purchase lands as a reserve for Indians forced off their lands on the east side of the continent, Benton insisted there should be no political limit to white settlement. There was simply no place for Indians in Benton’s imagined global order of the imperium of the city of St. Louis.16

Benton’s prophetic vision took the earthly shape of Indian wars. Indeed, the post–Revolutionary Army began as an Indian fighting force (the Patriots of the first generation were suspicious of standing armies in general, but devoted to Indian killing), with Benton’s St. Louis at the center of its strategic configuration. As early as 1804, General Nathaniel Wilkinson, in St. Louis to oversee the transfer of Upper Louisiana to the United States, outlined a vision of western dominion predicated on the control of the trade systems of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers once “we get possession of the interior of their country.” From 1805 until 1826, the army maintained a garrison at Fort Belle Fontaine, north of the city, near the confluence of the two rivers. It was on the grounds of the fort where William Clark signed some of the dozens of land cessions he negotiated during his time as the superintendent of Indian affairs. In the aftermath of the War of 1812, Wilkinson’s vision was taken up by then–secretary of war John C. Calhoun, who proposed the creation of a military line defending the northern boundary of the country from Great Britain, anchored to the United States through its connection to St. Louis. In 1826, the garrison at St. Louis was moved south of the city, to Carondelet, where the newly constructed Jefferson Barracks soon became the nerve center of the Army’s Department of the West. This arrangement was given official sanction in a series of military reforms in the 1830s and 1840s in which varied deployments of frontline forces were tied by supply lines and a chain of command that traced back to St. Louis. “In no other way, can an extensive line of frontier, like that of the United States, be defended by a small army such as ours,” wrote Secretary of War Joel Poinsett in 1843 of the idea of a far-flung arc of lightly defended forts reinforced by soldiers concentrated at a central hub—Jefferson Barracks.17

During the years leading up to the Civil War, about 80 percent of the army’s active-duty soldiers were stationed west of the Mississippi (179 of the army’s 197 companies in 1860, for instance) and depended upon Jefferson Barracks for their supplies, reinforcements, and marching orders. At this time, Indian wars and treaty costs (annuities, etc.) were by far the largest elements of the federal budget, and Jefferson Barracks was arguably the single most significant material manifestation of the United States of America other than the Capitol and the National Road. Between 1826 and 1865, every western Indian war fought by the United States was staged out of or supported from Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis: in addition to the Sauks and the Foxes, the Osages, the Winnebagos, the Ho-Chunks, the Comanches, the Pawnees, and the Sioux were all involved in significant battles with the United States in these years. Troops from Jefferson Barracks also played a central role in the Second Seminole War (1835–1842) in Florida, the Cherokee removal in Georgia, and the run-up to the Mexican-American War on the southwestern border. During that same period of time, virtually every officer who rose to prominence during the Civil War spent time at Jefferson Barracks—Braxton Bragg, Jefferson Davis, John C. Frémont, Ulysses S. Grant, Joseph Hooker, James Longstreet, Robert E. Lee, George Pickett, Philip Sheridan, William Tecumseh Sherman, James Stoneman, and J.E.B. Stuart. Before these men were legends, they were Indian fighters.18

In the decades before the Civil War, Indian fighting was big business in the city of St. Louis. In addition to the subcontracting of Indian removal and annuity payments to the Chouteaus and others in the city, the footprint maintained by the army at Jefferson Barracks provided merchants, manufacturers, and farmers throughout the region with steady income. St. Louis grocers and Missouri farmers provided most of the food consumed by soldiers (and later their horses) at Jefferson Barracks and at many of the army’s frontline bases. Indeed, the city provided much of the military hardware for most of the US Army: guns, ordnance, ammunition, uniforms, and eventually horses—all were provided to the government by merchants and manufacturers in the city of St. Louis.19

In other words, in addition to its overall strategic setting, the city of St. Louis had important connections to the developing defense industries of the first half of the nineteenth century. Jefferson Barracks sat midway between two of the richest lead belts in North America: one centered in Herculaneum and Potosi in southeastern Missouri (and controlled by the Chouteau family), and the other in Galena in the northwestern corner of Illinois. Lead was to the military-industrial complex of the nineteenth-century United States what rubber, then oil, then uranium, would be to the military-industrial complex of the twentieth century: an indispensable extractive resource. In 1824, when Congress doubled the tariff on lead, the industry exploded in the United States. The population of the lead district around Galena, where the federal government leased mining rights to settlers, increased twentyfold in the immediate aftermath of the change; subsequently, in 1827, 580 US Army soldiers were deployed from Jefferson Barracks under the command of General Henry Atkinson to inflict “exemplary punishment” on Ho-Chunk farmers who had come into conflict with the white settlers. In the years following, lead smelting grew into the first heavy industry in the city of St. Louis. When the New York merchant Phillip Hone toured St. Louis as the guest of Thomas Hart Benton in 1847, it was “immense piles of lead” on the levee that struck him more than anything else. By the 1840s, St. Louis boasted the largest smelting plant in the nation—providing the raw material of empire.20

The most famous war staged out of St. Louis in the years before the Civil War (though far from the only one) was the conflict that came to be known as the Black Hawk War in the summer of 1832. At stake were issues that dated to 1804, when a delegation headed by the Sauk leaders Pashipaho and Quashquame had traveled to St. Louis to meet William Henry Harrison. At the time, the future president was the territorial governor of the Missouri Territory, and his nickname, Tippecanoe, referred to his own legendary status as an Indian killer. The Sauk went to St. Louis to negotiate the release of a Sauk farmer who had been accused of killing three white settlers.21

The Sauk delegation had no authority to cede land, but Harrison nevertheless began by asking for land in return for a presidential pardon for the Sauk man he had in custody (and a promise not to pursue three others similarly accused who were not). Harrison kept no records of the negotiations, but Quashquame remembered that the Indians were “drunk the greater part of the time they were in St. Louis.” By the end of that time, according to Harrison, who had a signed treaty to prove it, in return for the release of one man, the Sauk had ceded most of what is today western Illinois, southwestern Wisconsin, and a small strip of eastern Missouri to the United States, including the sacred city of Saukenuk (known today as Rock Island, Illinois), the ancestral home of the Sauk.22

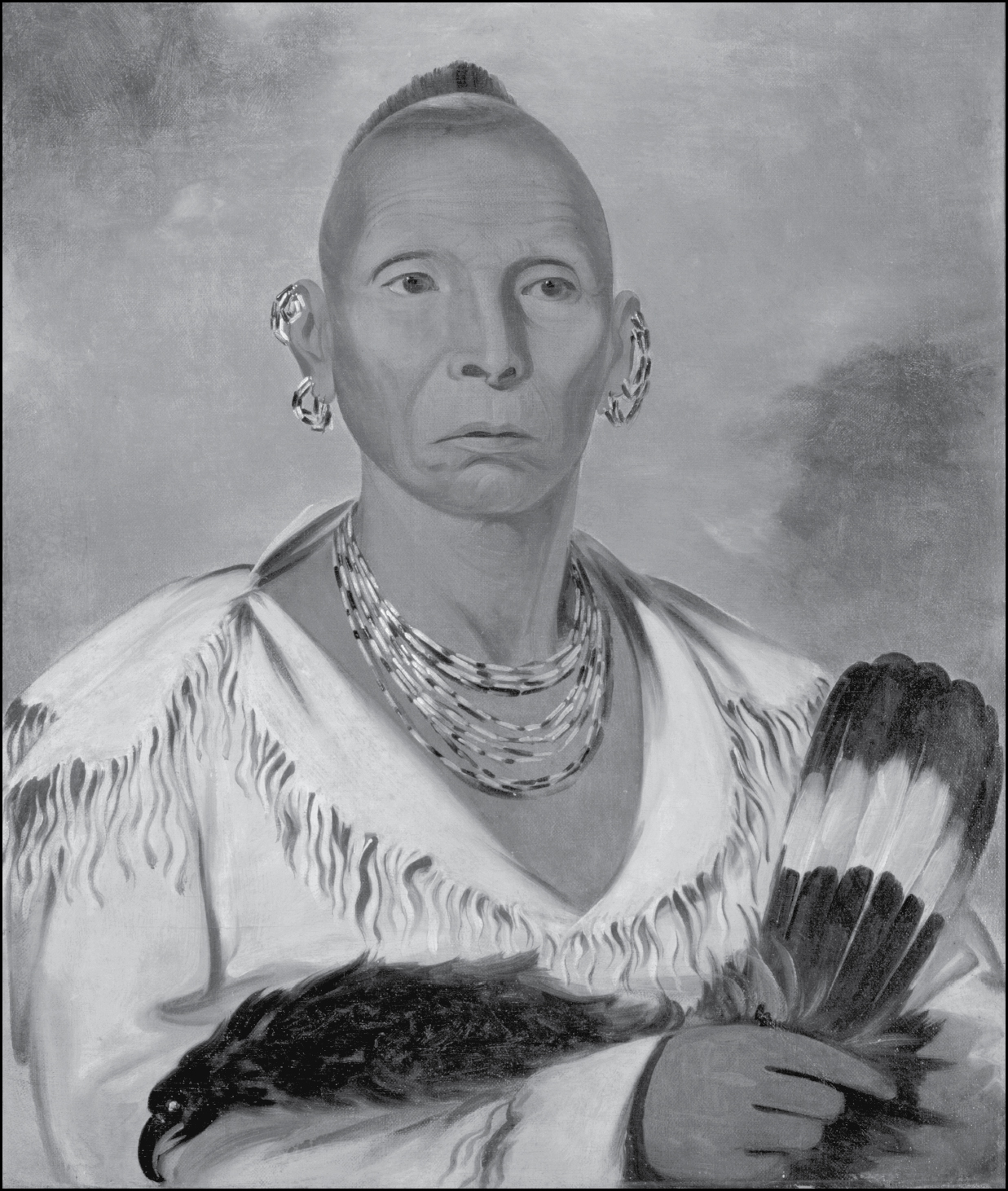

The Sauk and Fox leader Black Hawk led an effort to resist white settlers in Illinois in 1832. At the beginning of August, many of his followers were massacred by US soldiers operating out of Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis. This portrait was painted while Black Hawk was imprisoned in St. Louis following his surrender to Jefferson Davis, the future leader of the Confederacy. (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

The 1804 treaty, which provided that the Sauks and Foxes would continue to inhabit their ancestral lands up to the moment when the United States surveyed and sold them, never enjoyed a high degree of credibility among the Sauks and Foxes whose removal it promised. They stayed on the land and continued to gather at Saukenuk. In 1828, the federal government began to survey the lands in expectation of their sale, and Thomas Forsyth, the US Indian agent in Saukenuk, acting under the authority of William Clark in St. Louis, informed Black Hawk that the time had come—a quarter-century after the signing of the infamous treaty—for them to leave Saukenuk and move to the west side of the Mississippi.23

Much of what we know of the conflict that follows comes from the autobiographical Life of Black Hawk, which was dictated by the Indian leader to a translator (and recorded by an amanuensis) in 1833, after his capture and confinement at Jefferson Barracks. Life of Black Hawk is thus a slippery source. At best, it is a story told by a man who had little left to lose, but perhaps much to gain, by presenting himself in a way designed to placate his captors. Indeed, the book is dedicated to General Atkinson, the commander who oversaw both the war and its brutal denouement on the banks of the Mississippi. At worst, it is a mostly fabricated account composed out of the interaction of a loose translation and creative transcription. The enormous success (indeed, the bare existence) of Life of Black Hawk, however, suggests that, at the very least, the Sauk leader was canny enough to flatter his captors into allowing him to mount a publicity campaign for his people when he was, for all intents and purposes, a prisoner of war.

And yet the autobiography presents its central character as a bewildered naïf, more puzzled than outraged, at least in the first instance, by the ways of white settlers. On one occasion in the late 1820s, he remembered, “one of my camp cut a bee tree and carried the honey to his lodge. A party of white men soon followed him, and told him the bee tree was theirs, and that he had no right to cut it.” However much Black Hawk (and his scribes) might have exaggerated his perplexity at the property rights claimed by the white settlers, he was conveying to his audience the basis of the conflict between Indians and settlers over the meaning (and control) of land. In the winter of 1828, The Life tells us, Black Hawk, who was away hunting, received word that white settlers had arrived in Saukenuk and were fencing the land and destroying Indian lodges. When he returned to his lodge in the village, he “saw a family occupying it.” Again, even allowing for an increment of strategic literary effect, Black Hawk’s narrative conveyed the essential character of settler imperialism: one group of people moving into the houses of another, taking over the land they had cleared and cultivated, calling their actions progress, justifying them by race, and enforcing them by violence.24

Every spring after 1828, Black Hawk returned to Saukenuk, each year with a larger group. They repaired their damaged lodges and planted corn at the margins of the land that had been claimed by the whites. But the whites were running fences across the fields, and the Indian women who tended the crops “had great difficulty in climbing their fences… and were ill-treated if they left a rail down.” Often the whites plowed up the Indian corn. One hungry Indian woman was assaulted by a settler for eating a few ears of corn picked from the edge of “his” field; two others beat a young Indian to death for removing a rail from a fence that had been built directly across an Indian roadway. Black Hawk complained to Forsyth, and through Forsyth to William Clark, but heard back that Clark was receiving a constant stream of complaints about Indians from white settlers in Illinois. “THEY made themselves out the injured party, and we the intruders!… How smooth must be the language of the whites, when they can make right look like wrong, and wrong like right,” Black Hawk remembered in a passage that stands as one of the earliest analyses of the quicksilver process by which white entitlement is synthesized into feelings of white vulnerability and then back again into a standing justification of imperial aggression and white supremacist violence.25

While away for the winter hunt in 1830, Black Hawk received word from Saukenuk that the city had been divided into lots and sold. One of the white traders with whom the Sauks had once done business had bought a home lot on the site of the tribal graveyard and was plowing up the bones of their ancestors. In contrast to the white settlers, who based their claim to the land on imaginary lines drawn on the surface, Black Hawk rooted his people’s claim in the past and the earth. But the time for arguing had passed, and Black Hawk began to plan for war.26

Black Hawk had fought alongside the British during the War of 1812, and the Sauks and Foxes maintained trade ties to British traders in the Great Lakes region. He spent 1831 traveling around the Upper Midwest, consulting with other Indians and with British traders and agents. The following spring, Black Hawk had led his people, now known among the settlers as “the British Band,” back from their winter hunt to the east side of the Mississippi. By the middle of the month, his army had grown to about 1,100, enough to attract the attention of General Henry Atkinson, who was stationed at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis. When Atkinson received word that the Foxes had joined Black Hawk, he wrote to the governor of Illinois, James Reynolds. Informing him of the situation, Atkinson implied that Black Hawk was intending to attack white settlements, and he urged the governor to take whatever action he thought “proper.”27

Atkinson’s message to the governor signals the complex nature of the relationship between the US Army and the settler militias in the ethnic cleansing and annihilation of Indians in the 1830s. The official role of the army was to maintain peace while overseeing Indian removal. In practice, this often meant trying to avert conflicts between white settlers and Indians who—whatever their so-called representatives had agreed to, or been forced to agree to—were reluctant to leave their ancestral lands for ecologically and spiritually alien lands on the west side of the Mississippi. In times of war, however, the comparatively small regular army relied upon support from state militias. Which is to say that they mobilized the radicalized, leading-edge settler whites whose actions had occasioned the conflict in the first place.28

None of that is to suggest that the officers of the US Army resisted or even significantly mitigated the ethnic cleansing of the eastern United States. Removing Indians while writing anguished letters home (for example, William Tecumseh Sherman on the Cherokee) is still removing Indians. There is, however, an analytical distinction to be made between the sovereign imperialism represented by the US Army and by the settler colonialism of the white militias, between ethnic cleansing and annihilation. “The material was an energetic and efficient troop, possessing all the qualities except discipline, that were necessary in an army,” wrote St. Louis–based General Edmund Gaines of the Illinois militia in 1831. “They also entertained rather an excess of Indian ill-will; so that it required much gentle persuasion to restrain them from killing indiscriminately all the Indians they met.” It would not be long, however, before indiscriminate killing became the official policy of the US Army in Illinois and, not long after that, throughout the West. But, in Illinois in the summer of 1832, US Army officers were officially in command, but the actions and intentions of the white-settler militia determined the nature of the conflict—not least because, unlike the army, the settlers had horses and could operate well in advance of the trailing forces of the regular army.29

According to Black Hawk’s subsequent account, it became clear to him in the spring of 1832 that the hopes he had entertained of alliances with other Illinois Indians had been misplaced. Without hope of support from the Winnebagos and Potowatomis, whom he had believed would join him, nor from the British, whom he had believed would supply him, Black Hawk “concluded to tell my people that if the White Beaver [Atkinson] came after us, we would go back—as it was useless to think of stopping or going on without provisions.” He decided to make peace with the United States and move west. On May 14, 1832, Black Hawk sent three men under a white flag to assure Atkinson of his intention to return to the west bank of the Mississippi. When those men did not return in the expected time, he sent five others to see what had happened. Three men from the second party shortly returned at full gallop with the news that the two remaining members of the party had been killed, and that they were being pursued by “the whole army.” Black Hawk’s messengers had delivered his message not to Atkinson’s men, but to Reynolds’s—not to the regular army, but to the white-settler militia.30

Black Hawk later remembered that he had been preparing for a council with Atkinson when the men he had sent out under a white flag returned in full flight from the pursuing whites. He had only about forty men with him, but Black Hawk rallied them, saying, “Some of our people have been killed!—wantonly and cruelly murdered! We must revenge their death!” As the Indians advanced in alternating ranks, the white settlers began to turn and run. “Never was I so much surprised in my life as I was in this attack,” Black Hawk later remembered. “An army of three or four hundred, after having learned that we were suing for peace… that I might return to the west side of the Mississippi, to come forward with a full determination to demolish the few braves I had with me, to retreat, when they had ten to one, was unaccountable to me.” The militia’s leader, Isaiah Stillman, was unable to rally his men, some of whom only resurfaced after two or three days in full flight. Twelve of them remained behind, dead on the field. Among those eventually detailed to bury them was a settler militiaman who would later become the nation’s sixteenth president, Abraham Lincoln.31

For Black Hawk, whose force emerged intact from the battle, it was a Pyrrhic victory. After burying the two men Stillman’s rangers had killed and taking up the arms, ammunition, and provisions Stillman’s men had left behind, Black Hawk directed his band northeastward, toward Wisconsin. Everywhere the Indians went as they traveled, the white settlers of the Upper Midwest were hearing the news of Stillman’s Run and catching fire with rumors of an army of two thousand savages.32

General Atkinson, leading the combined forces of US regular soldiers from St. Louis and Illinois volunteers, had his own problems. Settler volunteers like those under Stillman’s command were, to the general’s way of thinking, unreliable and prone to outbursts of indiscriminate violence followed by serial desertion. He considered them a force unsuited to what was increasingly looking like an extended effort to track Black Hawk across a landscape that was known to very few whites in 1832. Through the month of June, Atkinson pursued and engaged raiding parties but was unable to capture Black Hawk, or even divert his northward progress. By the end of June, Atkinson’s struggles were national news. The general received word from President Andrew Jackson that he must bring the war to a “speedy and honorable termination” lest other Indians in other places come to see the army’s difficulty in capturing Black Hawk as a sign of more general weakness. Secretary of War Lewis Cass warned Atkinson that “an example [must] now be made” of Black Hawk. “A War of Extermination should be waged against them,” wrote William Clark, the superintendent of Indian affairs, from St. Louis. “The honor and respectability of the Government requires this: the peace and quiet of the frontier, the lives and safety of its inhabitants demand it.” The war had evolved from a conflict over the removal of the Sauks and Foxes into a campaign of exemplary genocidal violence led by the US Army—imperial annihilation designed to communicate to both the Indians and the settler whites that the US Army had the fortitude and the wherewithal to pacify the frontier.33

In Washington, the War Department began to organize a thousand-soldier expeditionary force (one-sixth of the entire regular army) under the command of General Winfield Scott to be sent to Illinois. But by the beginning of July, Black Hawk’s people had run out of food. “We were forced to dig roots and bark trees to satisfy hunger and keep us alive! Several of our old people became so reduced as actually to die with hunger!” Black Hawk later wrote of the last weeks of his march. He decided to try to work his way northwest, toward the Wisconsin River, in an effort to “remove my women and children across the Mississippi, that they might return to the Sac nation again.” Atkinson, closing in on the British Band and aware of the possibility that Black Hawk would try to recross the Mississippi, was determined to prevent the Indians from doing so. As the army pursued the Indians, the trail began to yield evidence of desperation—such as kettles and mats thrown away to cut weight in an increasingly headlong flight.34

Slowed by hunger and exhaustion, Black Hawk’s column made its way toward the river and what it thought was safety. “At length,” Black Hawk remembered, “we arrived at the Mississippi, having lost some of our old men and little children, who perished on the way with hunger.” The signs of starvation were everywhere along the trail that the soldiers and militia were following in pursuit of the retreating Indians: abandoned packs, butchered horses, and the emaciated bodies of the dead. Black Hawk reached the Mississippi near the mouth of the Bad Axe River on August 1, 1832. As the Indians prepared to cross, the steamboat Warrior, operating out of St. Louis, rounded a bend in the river. The Warrior had been chartered by the army to carry troops up from St. Louis. On board were fifteen regular army soldiers, six volunteers, and a six-pound cannon.35

Black Hawk knew the Warrior’s captain, who had traded along the Mississippi between St. Louis and Galena, Illinois, in the years before the war, and believed that he could convince him to let the women and children cross to the west bank of the Mississippi. He stood on the shore and waved a white flag. In response, the soldiers turned their cannon on the Indians and fired volley after volley of grapeshot. The slaughter went on for more than eight hours. “As many women as could, commenced swimming the Mississippi with their children on their backs,” Black Hawk recounted. “A number were drowned, and some shot, before they could reach the opposite shore.” On the other shore of the Mississippi, the Dakotas, Menominees, and Ho-Chunks—Indians who wanted the Sauks to stay in Illinois just as much as the white settlers wanted them to leave—were waiting. They killed many of those who managed to make the crossing and took many of the rest captive.36

The Black Hawk War ended there, near the mouth of the Bad Axe River, on the morning of August 2, 1832. “After the boat left us,” Black Hawk later remembered, “I told my people to cross, if they could and they wished.” Black Hawk gave himself up at the US Indian Agency at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, on August 27, 1832. Handed over from the Indian Agency to the army, he was placed by Colonel Zachary Taylor under the control of Lieutenant Jefferson Davis, who took Black Hawk down to St. Louis: “On the way down, I surveyed the country that had cost us so much trouble, anxiety, and blood, and that now caused me to be a prisoner of war,” Black Hawk remembered in defeat. “I reflected on the ingratitude of the whites, when I saw their fine houses, rich harvests, and everything desirable around them; and recollected that all this land had been ours.”37

After eight months of confinement at Jefferson Barracks, where he was forced to wear a ball and chain, Black Hawk was furloughed on the orders of President Andrew Jackson and taken on a tour of the eastern cities of the United States, the tour that occasioned the publication of Life of Black Hawk. Jackson’s intent was apparently to exhibit the defeated Black Hawk as a talisman of his own potency—“to be gazed at,” as the painter George Catlin put it—while also overawing him through a full-spectrum sensory exposure to the sights and sounds of industrializing America. Along the way, especially in the East, Black Hawk was treated as a heroic curiosity, especially after the publication of his Life, and large crowds of whites gathered to gawk at and applaud the conquered Indian in their midst. When he was released by the government near the end of 1833, Black Hawk settled in southeastern Iowa, where he died in October 1838 and was buried near the banks of the Des Moines River.38

For a time, Black Hawk was the most famous Indian in the United States. After dining with William Clark on Beaver Pond in 1832, Washington Irving rode down to Jefferson Barracks to gawk at Black Hawk in his cell and wrote about the experience in his Western Journals. The western artist George Catlin also rode out to Jefferson Barracks, where he sketched the captured leader, sitting in his cell. Catlin’s Black Hawk, painted in October 1832, sits stoically, in the artist’s words, “dressed in a plain suit of buckskin, with strings of wampum in his ears and on his neck, and [holding] in his hand his medicine-bag, which was the skin of a black hawk, from which he had taken his name, and the tail of which made him a fan.” His eyes seem fixed on a distant horizon, a view inaccessible to the viewer of the sketch. In reality, Black Hawk was looking out on the headquarters of the US Army Department of the West, the administrative center of the wars that the United States would wage against western Indians for most of the rest of the nineteenth century.39

The Black Hawk War was the final impetus for the transformation of the US Army into a force designed to fight Indians, a transformation that was centered in St. Louis. From the mid-1820s, commercial interests in Missouri, and especially in the city of St. Louis, had been insistently urging the militarization of the Santa Fe Trail, which connected St. Louis via St. Joseph, Missouri, to the Southwest and Mexico and was emerging as a principal source of wealth for city merchants. Indian attacks along the trail, editorialized the St. Louis–based Missouri Republican in 1825, were more than a threat to the lives and livelihoods of individual traders; they were “a public wrong, a national insult, and one which will bring down upon the heads of the guilty the strong arm of national power.” Never mind that the attacks took place in territory that was either Mexico or Comancheria, but definitely not in the United States of America. The deployment of the US Army along the trail in the late 1820s, spearheaded by Thomas Hart Benton, among others, represented a novel assertion of extraterritorial, indeed imperial, authority in the Southwest. It also, at least at first, represented a colossal failure. The foot soldiers deployed by the United States along the trail were no match for mounted Indian raiders—indeed, that was part of the point of the trail: horses taken from Mexico by Comanche raiders were sold through Santa Fe to St. Louis.40

The ongoing difficulty of patrolling the Santa Fe Trail, combined with the de facto subordination of the regular army to the mounted militia in Illinois and the national puzzlement at the army’s inability to capture the Sauk leader, prompted a midstream correction during the Black Hawk War—a transformation of doctrine in the War Department that would reverberate across the West for the next sixty years. In January 1830, the commanding general of the US Army reported to Congress that mounted troops were the only way that “the Indians can be properly punished, should they molest the inhabitants who are settled on the frontiers, or who may be engaged in the trade with Santa Fe.” And in April, the army’s quartermaster argued that mounted soldiers were the essential condition of continental empire: “The means of pursuing rapidly and punishing promptly those who aggress, whether on the ocean or on the land, are indispensable to a complete security; and if ships-of-war are required in one case, a mounted force is equally so in the other.” The deployment of mounted soldiers was inextricable from the emerging doctrine of exemplary punishment.41

The First Battalion of the US Mounted Rangers was formed at Jefferson Barracks in June 1832. Major Henry Dodge, still chasing Black Hawk across Illinois at the time, was appointed battalion commander; Captain Nathan Boone, the son of Daniel Boone, headed one company; Captain Jefferson Davis, upon his return from Illinois, was appointed to head another. By the end of the year, the mounted unit had been expanded to a regiment, renamed the US Dragoons, and permanently headquartered at Jefferson Barracks. Five of the ten authorized companies were fully outfitted and mounted on colored horses—grays, chestnuts, buckskins—matched to their unit. Even when the Dragoons left St. Louis for forward operating bases elsewhere in the West, Jefferson Barracks remained their primary base for intake and resupply. Based at Jefferson Barracks from the time of their creation, the US Dragoons (renamed the First Cavalry in 1861) took part in virtually every significant military action for the rest of the nineteenth century: action against the Seminole, Cherokee, Iowa, Kansas, Mahas, Pawnee, Potawatomi, Osage, Sauk, and Sioux, as well as service in the Mexican-American War, the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War. For most of the nineteenth century, St. Louis was home to the frontline force of exemplary imperial punishment: annihilation.42

Among the Dragoons, one man stood out: William Harney, the “Prince of Dragoons,” was athletic, imperious, vainglorious, and violent even by the expansive measure of the Age of Jackson. Born in Tennessee in 1800, Harney soon grew into the type of man whose character and practical morality were based solely on his greater size and strength relative to others. Harney was white supremacy and empire embodied. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the US Army in 1818, he was first stationed in Natchitoches, then Baton Rouge; by 1823, he was stationed at Jefferson Barracks.43

Along with other soldiers from Jefferson Barracks, Harney fought the Arikaras in 1824 and the Winnebagos in 1827. By the time of the Black Hawk War, Harney was notorious in the army for his stubbornness and volatility. At Jefferson Barracks, he refused to drill his men because of the pain caused by his gonorrhea, and he feuded with his commanding officer, Stephen Kearney. He viciously beat a dog that lifted its leg in the direction of his garden and tied a trader who sold whiskey to his soldiers to a post and beat him. Harney became close friends with Jefferson Davis and, later, Abraham Lincoln. He marched with the army that pursued Black Hawk to the mouth of the Bad Axe River and participated in the slaughter there.44

On June 26, 1834, in St. Louis, Harney beat an enslaved woman named Hannah to death. He had misplaced his keys and blamed her for hiding them. When Hannah’s body was discovered, there was a great deal of public outrage about the senselessness and wonton violence of the murder—enough to send Harney into hiding for a time. But by the time he returned to the city, his case had been assigned to a friendly judge, the aptly named Judge Lawless, who suggested that Harney was in danger of becoming the victim of the fury of an unreasoning mob and transferred the case to neighboring Franklin County—a markedly more proslavery jurisdiction. Harney was acquitted of Hannah’s murder after a daylong trial in March 1835. A little over a year later, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel and given command of the Second US Dragoons. By 1837 he was in Florida, fighting the Seminole. Perhaps it goes too far to see in his case an uncanny premonition of the unpunished murder of Michael Brown almost two centuries later.45

On the night of July 23, 1839, Harney was camped with a detachment of Dragoons along the Caloosahatchee River, east of present-day Fort Myers, when he was attacked by a larger group of Seminoles. Harney had spent the day hunting wild boar in the swamps, and his men had gone to bed without having been issued ammunition for their arms. When the attack came, they could do little but run. Harney himself fled in his socks and underwear, returning to camp only after daybreak to find that most of his twenty-two men had been killed, some of them mutilated. In September of that year, he wrote to his commanding officer, Zachary Taylor, who had just requisitioned a pack of Cuban bloodhounds to hunt the Seminole in the swamps. (Thomas Hart Benton was among the measure’s few civilian supporters.) “There must be no more talking—they must be hunted down as so many wild beasts,” Harney wrote. “Let everyone taken be hung up in the woods to inspire terror in the rest.”46

It was not long before Harney made good on his genocidal vision. In December 1840, near where the Miami River drains from the Everglades, Harney dressed a small company of Dragoons as Indians (a tactic seen as dubious even according to the corrupted standards of the Second Seminole War) and went in search of the Seminole leader Chakaika. When they came across two Indian families crossing the water in their canoes, they chased them down and hung the men in front of their wives and children. The next day they surprised Chakaika at camp and killed and scalped him. That night Harney hung the dead man’s body from a tree, along with two others, in plain sight of Chakaika’s wife and children, who had been captured earlier in the day. The Second Seminole War ground on for five more years—seven years all told, longer than any American war before Vietnam. Eventually around four thousand Seminole were removed to Oklahoma, including many Black Seminole—fugitives from slavery and their descendants, whose claims to being Indian would later be disputed by the “full-blooded” among the Seminole. After that December 1840 day in the Everglades, Harney’s historical reputation was firmly set. Henceforth, he was viewed as one of the army’s most merciless and effective Indian fighters. In St. Augustine that winter, the white citizens saluted Harney with cannon fire, a marching band, and a gigantic illuminated sign that read LIEUT. COL. WM. S. HARNEY—EVERGLADES—NO MORE TREATIES—REMEMBER THE CALOOSAHATCHEE!—WAR TO THE ROPE.47

Over the following years, Harney cemented his historical reputation as both a bully and a sadist. He reprimanded his men by grabbing their two ears and shaking their heads back and forth, and he punished soldiers who fought with one another by pitting them in punitive fights against slaves at Jefferson Barracks. Eventually court-martialed for abusing the men under his command, he was ordered suspended from rank and command for four months, with a recommendation that his suspension be itself suspended by his commanding officer. Harney served in the Mexican-American War between 1846 and 1848 and was delegated responsibility for hanging thirty of the legendary San Patricios—Irish Americans who fought for the Republic of Mexico. This he did by placing the men on the backs of wagons and forcing them to watch the climactic battle of the war unfolding in the distance with nooses hanging around their necks. At the culmination of the battle, the wagons were driven forward; Harney left the bodies hanging from the gallows. “I was ordered to hang them, and have no orders to unhang them,” he said.48

In 1854, stationed once again at Jefferson Barracks, Harney was selected by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to lead a punitive expedition against the Sioux. The expedition was designed as a retaliation for the so-called Grattan Massacre—the killing of twenty-six US Army soldiers who had begun shooting during a fairly routine piece of western diplomacy and ended up dead. Harney, commanding six hundred soldiers, including the Second Dragoons, caught up with the Brulé Sioux in September of the following year at Ash Hollow on the North Platte River in what is today western Nebraska. The leader of the Brulé, Little Thunder, rode out under a white flag to negotiate. Harney told the bewildered Little Thunder that he would not consider any terms, but that the “day of retribution” had come and the Indians “must fight.”49

While Harney sent the infantry northward after the retreating Little Thunder, his Dragoons circled east to block the Indians’ escape. As the Indians ran out through a narrow ravine, pursued by the infantry, the Dragoons fired down on them from above. By the time Harney’s men stopped shooting, eighty-six Indians were dead. Men, women, and children lay amid the detritus of their headlong flight, the things they had tried to carry away—the women’s moccasins, the children’s toys. “The sight,” remembered one of Harney’s soldiers, “was heart-rending.” In the aftermath of the massacre at Ash Hollow, General O. O. Howard termed Harney “the most renowned Indian fighter that we had.” From Harney’s perspective, the massacre was a perfect success; “the result was what I anticipated and hoped for,” he crowed in its aftermath. From that time forward, Harney was known among the Sioux as “Woman Killer.”50

It is for this man that Harney Avenue in St. Louis, running parallel to West Florissant, near the historical site of Fort Belle Fontaine and not far from the site of the Ferguson uprising in 2014, is named. In a way, it makes sense. For Harney is a perfect emblem of his age. He was not some frontier curiosity, a weird relic of another time, but a man who stood at the leading edge of the empire, pulling it into the future: lead, horses, and Indian fighting (the military-industrial complex of the nineteenth century); the militarization of the Santa Fe Trail and the Great Plains (the theaters of imperial battle for most of the remainder of the century); the annihilationist fury of Ash Hollow. If Thomas Hart Benton was the prophet of the westering imperium of the city of St. Louis, William Harney was its avenging angel: volatile, implacable, and unrepentant.

Genocide was the vanguard of the empire, and anti-Blackness followed immediately in its wake. In the South, and in the more familiar story, anti-Blackness took the form of slavery, and there was certainly slavery in St. Louis. But western anti-Blackness, the sort pioneered and promulgated in St. Louis, had as much to do with the model Indian removal and empire as it did with the exploitation of enslaved labor as it asserted its vision: there was no room at all for Black people—at least not free Black people—in the city of St. Louis.