4 | EMPIRE AND THE LIMITS OF REVOLUTION

Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the Black it is branded.

—KARL MARX, Capital

IN MISSOURI IN THE YEARS LEADING UP TO THE CIVIL WAR, the studied silence that had come to characterize the Bentonite approach to the question of slavery in the early 1850s—the doomed effort to insulate the promotion of the western empire from the question of whether or not white settlers would be able to own slaves—had given way to a more pointed argument over the proper relation of race, property, and empire. On the one hand were proslavery politicians, most of them Democrats, like Claiborne Jackson, the slaveholding governor of Missouri at the time of secession, and Sterling Price, the commander of the Missouri state guard who eventually oversaw the Confederate war effort in the state. Support for slavery was particularly strong in central Missouri’s hemp-producing Little Dixie region, the slaveholding counties along the state’s western boundary with Kansas, and among the St. Louis elite. For these Democrats, the questions of white supremacy, slavery, and expansion were aligned according to the logic of the Dred Scott decision: Black slavery and white ascendency without territorial limit.1

On the other hand, the election of 1856, in which John C. Frémont had been the presidential nominee of the new Republican Party, represented the national emergence of a powerful reworking of the question of the relationship of slavery to white equality, as prefigured in the removalist politics of the city of St. Louis and the state of Missouri between the second Missouri Compromise of 1821 and the attacks on free Black citizenship that had followed in its wake. These “free-soilers,” arguing that slavery raised one class of white men (slaveholders) above others (workers and farmers, the “producers”), fought to keep the institution out of the West, often with the codicil familiar to readers of the Missouri Constitution or the “Free Negro Bill” of 1859—that the West should be a “white man’s country.” As far as the West was concerned, however, and as far as Indians were considered, both the expansionist proslavery position of the Democratic Party and the settler whitemanism of the free-soil movement were simple variants on the imperialist theme that stretched back to Jefferson Barracks, Benton, the Black Hawk War, and beyond.

Captain John C. Frémont—“the Pathfinder,” the son-in-law of Thomas Hart Benton, and the founding figurehead of the Republican Party—was an imperialist and, by any modern standard, a war criminal. In April 1846, operating about nine hundred miles west of where he was supposed to be surveying a pass across the Rockies in Colorado, Frémont came upon about a thousand Indians—probably Wintus—gathered on the banks of the Sacramento River to catch salmon as they swam upstream. Though the reason for their assembly in the Sacramento Valley was obvious and easily explained, the Indians were rumored among nearby settlers to be planning an attack on a white settlement about ninety miles northwest of present-day Sacramento. For Frémont, that rumor of war was enough, and he ordered a preemptive attack on the large encampment. “The settlers charged into the village taking the warriors by surprise and then commenced a scene of slaughter which is unequalled in the West. The bucks, squaws, and paposes were shot dead like sheep and those men never stopped as long as they could find one alive,” remembered one observer. As the Indians fled on foot, Frémont led a mounted party that literally “cut a path through the fleeing crowd.” It was, as Frémont said of the Indians in another massacre in which he participated, “a story for them to hand down while there are any” left to tell it. It was, as the leading historian of the genocide in California has put it, “pedagogic slaughter”—killing in excess of any strategic justification, intended to demoralize the population into submission. Before he was through in California, Frémont would find himself at the head of a settler army and declare himself the leader of the short-lived (and arguably treasonous for a US military officer operating outside the chain of command) Bear Flag Republic.2

For Frémont and the Republican Party, empire (and thus Indian-killing) was the key to white freedom. In their imperial ambition, the Free Soil Republicans were the intellectual heirs of Benton, committed to the expropriation of Indian lands and their distribution to white settlers and to a transcontinental railroad. But where Benton had tried to defer the question of slavery, Free Soil Republicans sought to agitate it. The free-soil synthesis that formed the ideological infrastructure of the Republican Party that cohered around Frémont in 1856 suggested that white labor could thrive, and white men advance, only in the absence of slavery. For them, the future of Missouri as a “white man’s country”—as an empire—depended on the territorial limitation of slavery or even its abolition. The politics of the party was rooted in the material experience of the ambitious westering whites who had followed their hopes to Missouri in the decades after the War of 1812—Bentonite whites turned Free Soil Republicans. In the November 1860 presidential election, St. Louis voted two-to-one for the Free Soil Republican Abraham Lincoln over the proslavery Democrat Stephen A. Douglas.3

In the aftermath of Lincoln’s election, as the southern states began to secede from the Union and the United States prepared for war, St. Louis became a divided city. Sometime around Christmas Day in 1860, armed antislavery paramilitaries began training in the parks and parading in the streets of St. Louis. On New Year’s Day, armed men attended a court-ordered slave sale on the steps of the courthouse where the Dred Scott case had been heard a decade earlier and held the bidding on the first lot of people sent to auction to $8—their presence an implicit threat to anyone who dared bid more than the value of the clothes in which the slaves had been dressed for sale. (The moment was later commemorated in a famous painting by Thomas Satterwhite Noble misleadingly entitled The Last Sale of Slaves in St. Louis. The crowd returned to the courthouse on another day, and the enslaved people were sold; indeed, enslaved people in St. Louis continued to be sold southward by profit-taking owners well into the early years of the Civil War.) By the end of February, two months before the shelling of Fort Sumter, the streets of St. Louis were controlled by armed antislavery “wide-awakes” (thus known for the style of hat they wore) numbering about 1,400 men, divided into sixteen companies, many of them armed with Sharps rifles, the most deadly infantry weapons available on the planet in 1861.4

Proslavery Democrats in the city soon organized their own paramilitary units, the most notable called the “Minute Men” and led by Basil Duke, a St. Louis lawyer who would go on to fame as a Confederate general and chronicler of the Confederate war effort. The families of the old-money fur-trading and slaveholding elites, as well as working-class white Democrats and Irish immigrants (as much as 16 percent of the city’s population by 1860), looked to the state government and Democratic governor Claiborne Jackson for direction. At the behest of proslavery Democrats, Jackson placed the city’s police department under state control (where it remained until very recently). He then appointed a police board composed of four men whom the antislavery St. Louis minister Galusha Anderson later termed “three of the most outspoken virulent secessionists in the city,” led by Basil Duke. The police and the proslavery militias began to drill in the city’s parks and to march in its streets. The city, in the words of Anderson, was coming to resemble an “armed camp.”5

With the shelling of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, and the beginning of the war, all of the factors that had contributed to St. Louis’s position as the capital city of the nation’s western empire were transformed into strategic resources in the emergent struggle between North and South: control of the nation’s western waters and its best overland connections to the Pacific, the lead mines in Potosi and Galena, and the largest military base in the West. Years after the war, Ulysses S. Grant reflected on the strategic significance of the Union defense of St. Louis in 1861: “If St. Louis had been captured by the rebels it would have made a vast difference.… It would have been a terrible task to recapture St. Louis, one of the most difficult that could have been given to any military man. Instead of a campaign before Vicksburg, it would have been a campaign before St. Louis.”6

In the earliest days of the war, all of that strategic significance centered on the question of who would control the US arsenal located just south of the city’s downtown. In the weeks after the shelling of Fort Sumter, pro-Confederate state militias all over the South had been seizing federal arsenals, and the arsenal at St. Louis was by far the largest prize. As the arms depot of the nation’s western empire, St. Louis had the second-largest arsenal in the United States: 60,000 long arms, 1.5 million cartridges, 90,000 pounds of gunpowder, and 40 cannons. And in command was the man whose bloody record on the plains followed his murder of an enslaved woman named Hannah: General William S. Harney, the commander of the US Army Department of the West, the man the Sioux called “Woman Killer.”7

But as Lincoln’s national call for volunteers was ignored by Missouri’s proslavery governor and armed paramilitaries paraded in the city’s streets, Harney, known throughout his career for taking precipitate, even rash, action, moved with a deliberation that suggested an unspoken sympathy for secession to his critics. When he received orders from Washington to reinforce the arsenal, he moved three hundred men from Jefferson Barracks, but left the high ground above the riverbank depot undefended. When the Republican congressman (and Lincoln confidant) Francis Preston Blair Jr. tried to have the Home Guard, the antislavery paramilitaries, mustered into the US Army to defend the city, Harney refused to swear them into federal service or to provide them with arms. When General Nathaniel Lyon, who had direct command over the arsenal, suggested that some of the weapons stored there be transferred to Illinois volunteers who had been pledged to the United States by their governor, Harney asked to have his subordinate transferred. “He is a Southern man,” the well-connected Blair wrote to his friends in Washington; he noted in that letter that Harney was a chronically indebted slaveholder whose wife’s family owned a number of slaves he might one day hope to inherit. Not long after Blair sent his letter, General Harney was ordered to Washington to deliver a full report on the situation in St. Louis. Acting in his stead, General Lyon occupied the hills that overlooked the arsenal and mustered the antislavery Home Guard into the service of the United States.8

While Harney dithered, proslavery St. Louisans fell in behind Missouri’s Democratic governor, Claiborne Jackson. Acting under the authority of the state of Missouri, General David Frost called up about seven hundred volunteers and began to drill them at the edge of the city, at a place called Lindell’s Grove, near the site of present-day St. Louis University. They drilled beneath the flag of Missouri, called themselves the militia, and claimed to be acting as neutral peacekeepers in the divided city. But events left little room for doubt about their true purposes. The site soon became known as Camp Jackson, after the proslavery governor, and through Governor Jackson, Frost was in touch with Confederate commander Jefferson Davis, who arranged for artillery seized by the Confederacy from the US armory at Baton Rouge to be sent upriver to St. Louis, packaged and labeled as marble in order to escape attention. On the evening of May 9, 1861, local legend has it, General Lyon confirmed for himself what everyone already suspected. Disguising himself in women’s clothes, Lyon rode through Camp Jackson in a carriage owned by Blair’s widowed mother, a blind woman known for touring the city with her coachman. Whether the heavily bearded general actually rode around Camp Jackson disguised as a blind woman or instead observed the camp from the vantage point of a nearby ditch, as one of his German-speaking officers remembered, he saw enough to convince himself once and for all that General Frost was planning an attack on the arsenal. The state militia had taken down the street signs around their camp and replaced them with signs honoring the leaders of the Confederacy. Beneath those signs, boldly displayed, were the field pieces stolen from the armory in Baton Rouge.9

And so, around midday on May 10, 1861, General Lyon stole a march on Camp Jackson. Under his command were some eight thousand men—a small army composed of the army’s US Volunteers and locally organized Home Guards. As they spread out and marched in parallel columns down four different streets leading to Camp Jackson, many of the volunteers and all of the Home Guards received their orders in German.10

Throughout the 1850s, many in St. Louis used the word “white” in a way that would have been familiar to Thomas Hart Benton—as shorthand for a certain kind of person: a yeoman-farming or wage-working, vote-casting person. “Free soil, free labor, free men” went the slogan of the Republican Party to which, in Missouri at least, these men increasingly belonged. Their city had changed, however, in the decades since Thomas Hart Benton first championed Missouri to poor whites from Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky as the “best poor man’s country,” as the place where they might get out from under the bloated aristocracy of slavery and inherited privilege, escape competition with slaves and even free people of color, and get what was by right their own. These men, we will see, were well represented in the US Volunteers. But by 1860, one-third of the city’s population had been born in the German-speaking territories of Europe, and some of them had brought with them very different notions about property and democracy than those held by men like Benton and his Republican successors (not to mention those men’s more conservative antagonists assembled at Camp Jackson).11

The German-speaking population of the city dated to the 1830s, but the largest part of St. Louis’s German-speaking population had arrived in the city after the European revolutions of 1848. In that year, across large portions of continental Europe—France, Sicily, the German Confederation, and throughout the sprawling territories of the Habsburg Empire, from Milan and Prague to Budapest and Vienna—an anti-absolutist alliance of peasants, artisans and journeymen, students, and liberal professionals succeeded for a time in taking control of the cities and forcing the monarchs and their armies into retreat. The demands of the revolutionary alliance spanned the spectrum from the introduction of constitutional monarchy and the “rule of law” to the redistribution of land and, in the most radical cases, the abolition of private property. In time, however, the monarchists regained their footing, and taking advantage of the fear of too-radical change among the moderates who had opposed them, used their overwhelming military force to crush the revolt. Many of the defeated revolutionaries, including the most radical among them, were forced into exile and fled to Switzerland, London, the Ottoman Empire, and the United States, especially St. Louis.12

In St. Louis, as elsewhere in the United States, German-speaking immigrants were met with nativism and violence. Many native-born St. Louis whites resented the Germans, who they thought would take away their jobs and diminish their political power, and the politics of the city in the 1850s was shaped around sharp divides between nativists and immigrants, cutting across both the Republican and Democratic Parties. Jealous of their office and political emoluments, both old-line Whigs and working-class white Democrats resented German (and elsewhere, Irish) voters, and officeholders. The Order of the Star Spangled Banner, a nativist political party, emerged nationally in 1856 and captured the state governments in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, although only after they rebranded themselves as the Know-Nothing Party. (The name referred, not to their being ignorant xenophobes, although one could surely make a case for that, but to the response they were bound to make to any questions about the semi-secretive workings of their party: “I know nothing.”) In the 1855 municipal election in St. Louis, Know-Nothingism divided the Bentonite Democratic Party and took control of the city. “Crass nativism and intolerant temperance oppressed the entire population with an iron hand,” wrote the newspaper editor, theater owner, and brewer Henry Boernstein (for whom nativist attacks on German beer halls and breweries were particularly galling). “The people were held in virtual slavery through restrictions on their freedom” enforced by the native-born police force.13

In the German neighborhoods of South St. Louis, men organized themselves into hunting clubs, which served the dual function of recreation and armed self-defense. The iconography of anti-German nativism focused mostly on beer and potatoes, but beneath the tired jokes was a deeper disquiet: many of the German immigrants to St. Louis were experienced political organizers, and some of them were quite radical. There were German slaveholders in St. Louis as well as Germans who cared very little one way or the other about the issue, but it was Germans who in 1861 would form the backbone of the Union Army in St. Louis. These were men who had fought against monarchical rule and hereditary privilege in Europe only to come to the United States and find a variant form of aristocracy in the entrenched power of slaveholders. For some of them, free-soil politics made the same sort of sense that it did to the non-slaveholding settler whites who were the bedrock of the Republican Party. And for an influential few, the struggle against slavery offered an opportunity to continue a struggle not simply against inherited privilege, but against property itself.

The commanders of the regiments that marched on Camp Jackson provide an emblematic roll call of the politics of Unionist St. Louis: there was a regiment of US Volunteers under the command of the Bentonite Republican Francis Preston Blair Jr., known in St. Louis as Frank; a regiment of German-speaking Home Guards under the command of Nikolas Schüttner, a German brickmaker from South St. Louis; another regiment under the command of the German immigrant theater impresario and newspaper editor Henry Boernstein; and yet another under the command of Franz Sigel, a veteran of the revolution in southwest Germany and a military theorist who would soon become the most famous German in the Union Army. Held in reserve were still more Germans, under the command of the Republican political leader B. Gratz Brown. They were united by their opposition to slavery, although there were deep differences among them about the question of “freedom”—about what, concretely speaking, the overthrow of slavery would mean for Black people, for Indians, for settler whites, and for property in general. In the end, it would be the politics of the neo-Bentonite Republicans—imperialists whose greatest hope for African Americans was that they would get out of the way—and the liberal (not radical) Germans that would point the nation’s course. But that, again, is getting ahead of the story.

Saturnine and handsome as he led his troops up Laclede Street toward Camp Jackson, Frank Blair was the namesake and third son of one of the most powerful Democratic politicians of the Jacksonian era, and he had become a Free Soil Republican by the time of the Civil War. It was the younger Blair, as much as anyone other than Frémont, who transformed the Bentonite vision of settler colonialism and Pacific empire of the 1840s into the free-soil imperialism of the 1850s. His most famous speech, “The Destiny of the Races of This Continent,” delivered in Boston in 1859, began where Benton left off: with a vision of American commercial empire that linked the Atlantic to the Pacific by way of a “great national highway between the oceans”—the imperium of St. Louis. Blair found in Indian removal an example for the process by which Blacks might be removed from the central commercial corridor at the heart of his vision of national and imperial greatness. “The races of this continent” could flourish only if separated from one another, each allotted to the climate that suited them best, their “true zone” of hemispheric habitation: Blacks in “the tropics,” white “redeemers” in the “temperate central latitudes,” and “wild beasts and the wild tribes of men who pursue them” pressed out to the margins of white settlement and finally southward into Mexico.14

For Blair, the alternative to emancipation, colonization, and expulsion (“the gradual transfer of four million of our freedmen to the vacant regions of Central and South America”) was what would today be called “white genocide.” Black slaves would out-reproduce working-class whites until “the wages of free labor would be so reduced as to destroy its existence.” “All who labor” might soon be reduced to “the condition of Slavery.” Neither Black nor working-class whites, he warned in a pointed invocation of the language of the Dred Scott decision, “will have rights which those holding power in the state are bound to respect.”15

Blair’s free-soil synthesis of the history of Native American genocide and white supremacy stopped short of calling for an end to slavery; his family’s roots were in the Democratic Party, after all, and he was himself a slave owner in 1860. But in 1857, Blair’s cousin and sometime political rival, the St. Louis newspaper editor and state representative B. Gratz Brown, had done just that, outlining a free-soil position that was equal parts antislavery and white supremacy. For Brown, who rose in a debate in the Missouri House to speak in favor of the gradual emancipation of Missouri slaves, the question of “humanity”—indeed, the question of “the emancipation of the black race”—was of no independent concern. He spoke instead of “The Emancipation of the White Race.” As he explained, “I seek to emancipate the white man from the yoke of competition with the Negro.”16

Brown is often remembered as a radical, and that is certainly how his proslavery colleagues in the Missouri House viewed him; they received his speech with a slack-jawed horror that gradually thickened into dyspeptic nausea. His political vision, however, was framed by the historical limits of his experience in St. Louis—that is, by the logic of ethnic cleansing that framed the Missouri State Constitution, Indian removal, the free Negro laws, and the Dred Scott decision. And above all, his vision was shaped by the politics of empire, commerce, and the railroad. If Brown’s opposition to slavery turned out on further inspection to be an aspect of his devotion to white men, that devotion itself turned out to be an aspect of his commitment to a Bentonite vison of western empire, and especially to the railroad.

In the decade before the Civil War, the state of Missouri spent more money on railroads than any other state in the Union. Construction had begun on the Pacific Railroad line, originating in St. Louis, in 1851. Though construction was slow, by 1855 the line had reached Jefferson City, the state capital, about 120 miles west of St. Louis. On November 1, 1855, many of the city’s leading citizens, including the mayor and several prominent railroad investors, set out on an inaugural trip on the Pacific line to Jefferson City. In the early afternoon, about 90 miles out, they reached the Gasconade River, where a temporary trestle had hurriedly been built to support an unfinished bridge so that it could accommodate the vanity train ride. Overnight rains had turned the banks of the river to mud and loosened the moorings of the temporary bridge, and as the train headed out over the river the trestle began to lean, and then it collapsed. Forty-three people died in the river, many of them crushed beneath the weight of the locomotive, which fell backward on top of the first coach, in which many of the dignitaries rode.17

By the time of the Gasconade disaster, the politics of railroads and the politics of slavery in Missouri had become as twisted together as the rails over the Gasconade, and with much the same result. The Kansas-Nebraska Act (introduced by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois in an effort to provide the federal jurisdiction necessary to expropriate Indian land and protect railroad property) had established “popular sovereignty” (that is, a territory-wide referendum) as the mechanism for deciding the future of slavery in the West. The new standard, an explicit repudiation of the Missouri Compromise, had set off a contest over migration to Kansas between easterners on either side of the slavery question. The competing migrations soon developed into a shooting war in “Bleeding Kansas,” which was a direct precursor of the Civil War and the occasion for the emergence of “Osawatomie” John Brown and “Bloody Bill” Anderson, for the Lawrence Massacre, and for the caning by Congressman Preston Brooks of Senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the US Senate.

A direct rail line from St. Louis was understood by those on both sides of the conflict in Kansas as a potentially decisive strategic advantage for the free-soil side of the struggle, and so railroad bills were repeatedly obstructed and slow-walked by proslavery representatives in the Missouri legislature. Among those most concerned with capitalist development and imperial expansion, the functionally proslavery imperialism of Thomas Hart Benton, who had hoped to endlessly defer conflict over slavery until the railroad reached the Pacific, gave way to the antislavery imperialism of the free-soil movement and the Republican Party. This slow-rolling transformation in Missouri politics was dramatically accelerated by Gratz Brown when he rose in the state legislature in February 1857 to denounce proslavery Missourians for standing in the way of the city’s western empire and effectively delivering commercial control of the Missouri Valley—the wellspring of the city’s wealth and its history—to Chicago. If forced to choose between slavery and empire, Brown declared, Missouri should choose empire and set about making plans to emancipate its slaves.18

For Brown, the combination of empire, emancipation, and annihilation held the key to freedom—for white people. “Paper edicts and proposed statutes will be of little force or effect until population—and free white population at that—shall insist upon its rights of labor and supply that great substratum upon which society rests for support.” It was white people themselves, through the act of being white and moving to Missouri, who would abolish slavery: “The African race and its concomitant slavery, will go down and vanish in these United States as the Indian race has gone down and vanished beneath the tread and march of the Anglo-Saxon and nothing else under God’s blue heaven will ever supplant it in the State of Missouri.” As to what would happen to the slaves whom nature had condemned to recede before the Anglo-Saxon advance, Brown was fairly vague—he assumed that their owners would be compensated for recognizing the racial writing on the wall and acceding to the “deportation” of their human property.19

At the head of a column that marched along Olive Street was the beady-eyed, nervous, and observant Henry Boernstein, whose mutton-chop-and-mustache chinless beard was reminiscent of the Austrian emperor against whom he had fought in 1848. Boernstein was the editor and publisher of the Anzeiger des Westens, a German-language paper printed in St. Louis. After growing up in Austrian Galicia, he had made his way to Paris with a company of traveling actors. In Paris, he settled in among that city’s radical émigrés and fell under the influence of the brilliant and charismatic Karl Marx. In 1844, he took over a theretofore moderate weekly newspaper and transformed it into a vehicle for the city’s emerging radical leftists: Marx, Heinrich Heine, and Karl Ludwig Bernays. The paper was suppressed by the French government in 1845, and Boernstein emigrated to the United States, first to Illinois and then to St. Louis. In St. Louis, Boernstein became a fervid supporter of Thomas Hart Benton, whose efforts to distribute the public domain to working-class migrants had become a model for one stream of radical thought in Germany during the 1840s.

Boernstein, that is to say, fell victim to a problem that has bedeviled the American left down to the present day: a failure to reconstruct a vision of democracy rooted in European social theory around the specific history of the United States. In Europe, the land radicals like Boernstein imagined redistributing to the propertyless the land that belonged to aristocrats; in the United States the land belonged to Indians. European radicalism translated to the American context could become a vexed whites-only liberal imperialism, a tendency that Boernstein seems to have exemplified in the years leading up to the Civil War. In those years, Boernstein became a political supporter and ally of Frank Blair and Gratz Brown, serving for the latter as a liaison to the city’s German neighborhoods. In Missouri, Boernstein’s revolutionary liberalism was translated into a variant strain of the aspirational whiteness of so many of the migrants who had followed Benton west—the settler vanguard of the white man’s country who had turned to free-soil politics as a way to preserve the West for themselves. As much as to end slavery, Boernstein went to war in defense of the rights of white men to hold property in the imperial West.

A block to the south, Franz Sigel marched along Pine. By the time Sigel had arrived in St. Louis in 1857, he was already a renowned revolutionary. Of medium height, slim and severe, with hollow cheeks and deep-set dark eyes, he looked like Johnny Depp dressed up to play Dracula. When the revolution broke out in Baden in March 1848, he had been one of the few men among the revolutionaries with any military experience, and in 1849 he became the war minister of Baden’s provisional revolutionary government. With the defeat of the revolution, he fled to Switzerland, where he contributed to a study of the revolution (Geschichte der Süddeutschen Mai-Revolution) that was intended to provide a manual of practical instruction for imagined future revolutionaries.

This handbook for aspirant revolutionaries combined a reading of the German military theorist Carl von Clausewitz with the political economy of the Communist Manifesto. Clausewitz had argued that “general insurrection” was a “natural, inevitable consequence” of modern warfare, and that the revolt of people against their leaders was of decisive importance in the conflict between states. Sigel and his co-agitators combined Clausewitz’s argument with their own experience in 1848 and their communism to conclude that a “total levy”—the militarization of the common man—was both good strategy (Clausewitz) and good politics (Marx). “Red republicans, the socialist democrats, have as their political principle the solidarity of all peoples; they know that, in the freedom struggle of any one land, the fight is for freedom of all humanity,” they wrote. “This governing principle secures from neighboring lands not just sympathy, but concrete assistance.” Their views tracked Sigel’s own, which Andrew Zimmerman, the most careful scholar of his political thought, has termed both “revolutionary” and “anti-capitalist.” “Strictly speaking, there is no such thing as property,” Sigel wrote after arriving in New York in 1852, before going on to declare, “We, the socialists, are the Muslims of the modern World. In one hand, the Quran—our Quran—in the other the saber—need commands it.”20

Sigel’s political writings are aphoristic, abstract, written in an archaic alphabet, and almost illegible. They are punctuated by harsh declarations (“war is the teacher of politics”) and portentous dialectics (“the revolution must unite beast and spirit; it must humanize society”). And they outline a vision of the world in which revolution, class conflict, and the uprising of slaves against their masters were distinct aspects of a single struggle toward human emancipation: “The socialist and communist has to want Revolution even in its mildest form, just like the worker has to want the worst work. But both must, through superior effort and superior talent, gain dominion [Herrschaft] over the masters. The slave must make himself master [zum Herren machen].”21

He sought, he wrote, to develop a “system of war” that would join the talents of “soldiers” to the aspirations of “communists” in launching an anticapitalist “crusade” from their redoubt in the United States. When the war began with the shelling of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Franz Sigel had already been organizing working-class German radicals into paramilitary self-defense battalions for over a year. And when the first significant military action following the shelling of Fort Sumter (and the first significant Union military victory) occurred in St. Louis on May 10, 1861, Sigel was in the midst of the fight. Almost immediately, he became a hero to German Americans, and going to “fight mit Sigel” became a tagline for the 200,000 German-born soldiers who eventually fought in the Civil War.22

That’s the long version of the story. The short version is this: Sigel, one of the most celebrated figures in the history of Civil War St. Louis and the Civil War, a man whose service is today memorialized in a striking twenty-foot statue in St. Louis’s Forest Park, was a stone-cold communist.

And then there was Nikolas Schüttner, who marched along Market, a block south of Sigel, at the head of a regiment of erstwhile paramilitaries who had been mustered into the service of the United States. Huge and heavily bearded, the brickmaker Schüttner was the longtime leader of the Schwarze Jager, or Black Hunters, a rifle club based in the German neighborhoods of South St. Louis that had been marching in the streets of St. Louis since the beginning of the year. The members were mostly veterans of the European wars of 1848 and 1849, “strong, bearded, full-grown men” who owned their own weapons and marched with a menace that caused what one onlooker termed “holy fear” among the proslavery Minute Men with whom they contended for control of the streets. With Schüttner, too, were three armed companies of Turners, members of the Turnverein, or Turner’s League, whose sports club (the Turnhalle) was one of the poles of German social life in St. Louis. Almost two hundred of them had been training for armed combat since the beginning of the year and carried arms that had been bought by the Turnverein after an appeal to its members.23

The German-speaking soldiers who marched with Schüttner and the others held a variety of views about slavery and race. Along with radicals like Sigel, who saw the struggle against slavery as part of a larger revolutionary struggle against property, there were many who took a different view of the relation between slavery, freedom, property, and empire. Like aspirant white settlers, many previously agnostic Germans felt threatened by the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the possibility of the westward extension of slavery. Slavery in Kansas would mean lower wages in St. Louis (as wealthy slaveholders bought up all the land that provided wage workers with an alternative to poorly paying jobs, or so the argument went). More than that, it was not even clear whether Germans would be allowed to vote in the elections that would decide the future of slavery in the West. The debates over the Kansas-Nebraska Act had featured a long sidebar about whether or not non-naturalized German immigrants would be allowed to vote in Kansas at all. Among the German readers of Boernstein’s Anzeiger des Westens, it was an article of faith that slaveholders viewed German workers as men in need of masters, indeed, as “white n—s.” Like Blair or Brown, many Germans supported the territorial limitation of slavery or even gradual and compensated emancipation out of concern for their own interests rather than out of any concern for the slaves—they were anti-slaveholder and anti-Black as much as they were antislavery.24

At the head of the forces marching on Camp Jackson was Nathaniel Lyon, a Connecticut-born graduate of West Point and recent veteran of the terroristic paramilitary border war in Kansas. Like William Harney, the man whom he was replacing as interim commander of the US Army Department of the West, Lyon had been an officer in the First US Dragoons. Eleven years earlier and two thousand miles to the west, near Clear Lake in California, Nathaniel Lyon had led a company of Dragoons on an expedition against the Pomo. His orders were “to chastise the Pomo.” Many of the Pomo had reportedly been held on the west side of the lake by a couple of self-styled grandees in a sort of settler-gothic slavery—raping the women at will and driving the men to death mining for silver. In the spring, the Pomo on the west side of the lake rose up and killed the whites; some then went to an island at the north end of the lake, where hundreds of Pomo had gathered to participate in an annual gathering. Representing the US Army, Lyon marched on the Pomo gathered on what came to be called “Bloody Island” and killed as many as two hundred of them. “Little or no resistance was encountered, and the work or butchery was of short duration,” reported the Daily Alta California, “nor sex, nor age was spared, it was the order of extermination fearfully obeyed.” Lyon and his men then moved west, toward the Russian River, where, according to a Pomo survivor, they killed seventy-five more, “mostly women and children,” whom they chased through the thick brush surrounding the Pomo camp and killed with their bayonets, hatchets, and knives. The massacre at Bloody Island, argues the leading history of the genocide in California, was one of the largest in the history of North America, and it marked the moment when the full force of the US Army was brought into alignment with the murderous white settler government of Gold Rush–era California.25

Just as the political philosophy of the more conservative of the Republicans drew on images of Native American dispossession and disappearance to frame their predictions about the western apotheosis of the white man, the military careers of the radical Republicans emerged out of the crucible of empire and Indian killing. And just as their radical German supporters and allies brought with them to Missouri a vision of war-making that was inseparable from their vision of social transformation—a revolutionary vision—men like Lyon brought the experience they had gained in California to the war they fought in Missouri—uncompromising, brutal, civilizational, total war.26

By the time the federal forces reached Camp Jackson, a large crowd of onlookers had gathered, waiting to see what would happen. Among the crowd of observers at Lindell’s Grove that day were two men whose names would become bywords for pedagogic, punitive, total war over the course of the Civil War: Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. Grant’s first posting after he graduated from West Point in 1843 was to Jefferson Barracks, and it was in St. Louis that he met his wife, Julia Dent, the daughter of a slaveholding farmer. Posted to California in the years after the Mexican-American War, he was rumored to have begun drinking regularly, and to excess. He resigned from the Army in 1854 and returned to farm his wife’s property (and oversee her family’s slaves) in St. Louis County, south of the city. Grant was an indifferent farmer, and in 1860 he quit altogether and moved with his family to Galena, where his father had offered him a job and a regular income in his tannery. (His wife’s property would later be incorporated into the estate of the beer-brewing Busch family, Grant’s Farm.) When Lincoln sent out the call for soldiers after the attack on Fort Sumter, Grant raised a company of men and was commissioned as a captain in the Illinois Volunteers. In May 1861, Grant was stationed at Belleville, Illinois, across the river from St. Louis, and he had come to the city out of professional curiosity, which quickly hardened into the murderous fury for which he was later known: “After all, we are not so intolerant in St. Louis as we might be,” he wrote from the tense city. “I have not seen a single rebel hung yet, nor heard of one; there are plenty of them who ought to be, however.” Early in the afternoon of May 10, Grant reached Lindell’s Grove just as Lyon’s column approached and, to quote legend once again, wished the general good luck moments before Lyon laid siege to Camp Jackson.27

Also at Camp Jackson that day was William Tecumseh Sherman. After graduating from West Point, Sherman had fought in the Second Seminole War and in the Southeast, where he participated in the removal of the Cherokee. He spent the years of the Mexican-American War on an exploratory expedition to Brazil (along with Henry Halleck, who would command the Department of the West from St. Louis in the latter years of the Civil War), and like Lyon and Grant, he was stationed in California during the years of the genocide. In 1853, Sherman resigned from the army to become the principal of the San Francisco branch of the St. Louis–based bank Lucas, Turner, and Company (the Lucas in question being a descendant of the fur-trading and land-speculating St. Louis Lucases). Several ventures later, Sherman was in St. Louis, where, in 1861, he began a job as the president of the St. Louis Railroad Company, a streetcar company connecting the city’s expanding western suburbs to the downtown. On the afternoon of Friday, May 10, Sherman was at Lindell’s Grove with his young son, waiting, along with the rest of the crowd, to see what would happen. Sherman, perhaps the most infamous of all Civil War generals, began the day as a retired military man who had turned to business. By nightfall he had witnessed one of the earliest skirmishes of the Civil War. By the following Tuesday, Sherman, who had been skeptical about Lincoln’s call for volunteers a month earlier, had been commissioned as a colonel in the Union Army and given command of the Thirteenth Infantry, which was being organized at Jefferson Barracks.28

At 3:15 in the afternoon, as his forces deployed around Camp Jackson, Lyon gave General Frost a half-hour to surrender. Frost, who was outnumbered by ten to one, had little choice but to comply with a demand that he nevertheless insisted was “illegal and unconstitutional.” Sigel’s regiment disarmed the rebels and took control of the weapons that had been shipped upriver from Baton Rouge. Frost’s captured men were divided into two columns, one superintended by troops under the command of Frank Blair, the other by troops under the command of Henry Boernstein. Around six o’clock, as the federal band struck up “The Star-Spangled Banner” and the troops started marching their prisoners to the arsenal, some in the crowd began to jeer at the German soldiers—“Hurrah for Jeff Davis” and “Damn the Dutch”—and to throw stones at them as they passed. No one knows who fired the first shot, or indeed whether it was fired by a soldier in the ranks or an armed onlooker, but there was an exchange of gunfire from both sides. Many in the crowd panicked and crushed one another in what Sherman later termed a “stampede.” There with his son, Sherman crouched behind an embankment during the gunfire and then “jerked” his son by the arm into a gully in the surrounding grove of trees when the soldiers paused to reload. By the time the soldiers stopped firing, twenty-eight of the onlookers were dead.29

For several days, the city of St. Louis teetered on the brink of an all-out war. As the soldiers returned to the arsenal with their secessionist prisoners, they were surrounded by a crowd that threatened to “lynch” the prisoners of war. Armed mobs roamed the streets. Saloons and restaurants boarded up their windows, and citizens barred their doors. The US Volunteers, the German Home Guard, and the St. Louis Police all deployed in the street to show force and claim turf in the time-honored name of “keeping the peace.” On the night of the eleventh, as Home Guard troops paraded through the downtown, an ambush by a group of armed men hiding amid the columns of a Presbyterian church on the corner of Walnut and Fifth Streets left six dead. Rumors spread through the German neighborhoods on the Southside (known to this day as “Germantown”) that “the American-born citizens to the North were coming down to loot and burn their dwellings and kill them.”30 Boernstein recalled crowds gathering in front of the Planter’s House Hotel and the courthouse shouting at the troops as they passed—“damned Dutch” and “Hessian hirelings”—and threatening to “exterminate” the Germans. Both the Demokrat and the Anzeiger des Westens were targeted and put under armed guard.31

Still, it was clear who had won the battle, and slaveholders and southern sympathizers, including some of the wealthiest families in the city, began to make plans to leave. “Sunday morning presented the spectacle of the general flight of the ‘upper ten,’ the rich proud slaveholders who had looked down on the Germans only twenty-four hours before with such contempt,” remembered Boernstein. “Coaches from every livery stable, furniture wagons, drays, and every sort of vehicle was requisitioned. The best furniture, trunks and chests with clothing and linen, women and children, and anything that was not nailed down were loaded up” and hauled down to the levee, awaiting shipment out of town.32

General Harney returned to St. Louis on May 12 and deployed regular army troops to keep the peace in St. Louis. A wary quiet settled over the city. For a brief moment, even the skeptical Francis Blair thought that Harney had returned from Washington a changed man: the general was unequivocal in terming the action taken by Frost at Camp Jackson “unconstitutional” and illegal, and he ordered his troops to search the city’s Confederate-aligned police stations, where they discovered several of the cannons that had been shipped from Baton Rouge. But by the end of the month, Blair had tired of Harney’s insistence on treating the statements of Claiborne Jackson, the state’s proslavery governor, and Sterling Price, the commander of its proslavery militia, as if they were reliable. Again and again they assured Harney that they were neutral actors committed to “keeping the peace” in Missouri, and again and again their best efforts fell short of actually ending the attacks of proslavery “bushwhackers” on their antislavery, unionist, or even agnostic neighbors. By the end of the month, Blair had presented Harney with a letter from Abraham Lincoln that reassigned the general to Washington, effective immediately, and elevated Nathaniel Lyon to commander until a permanent commander could be found for the Department of the West. Blair had been carrying the letter in his pocket for weeks, a trump card he could no longer hold in reserve.33

Once Lincoln’s order was revealed, Lyon acted quickly. Even before Harney’s removal, Lyon had overseen the fortification of the city, setting up checkpoints at the rail stations and river landings and ordering that every conveyance be stopped and searched on its way into the city. He had likewise ordered the military occupation of Potosi, downriver from St. Louis in Washington County, where federal troops had taken control of over sixty thousand pounds of lead. Now fully in command, he met with Jackson and Price at the Planter’s House Hotel in St. Louis. After several hours of fruitless discussion, Lyon abruptly ended the meeting: “Rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any manner, however unimportant, I would see you… and every man, woman, and child in the state dead and buried.” And then, in case they had missed the point: “This means war.” Lyon provided his visitors with safe conduct through his lines and began to plan his attack on the state capital. As they traveled back to Jefferson City, Jackson and Price ordered that the railway bridges over the Gasconade and Osage Rivers be burned behind them.34

Lyon’s march across Missouri has been largely forgotten by a Civil War historiography focused on the eastern theater and the Battle of Manassas, which was fought on July 21, 1861. Lyon’s battles in Missouri, however, were the only Union military victories in 1861; more than that, the actions taken by his army presaged the course of the war. For as Lyon’s army worked its way across Missouri, the conduct of some of its officers and many of its soldiers began to diverge from the orders they were receiving from Washington. Many of the soldiers in Lyon’s army adopted a genuinely “revolutionary” strategy: to fight a war against slaveholders, they had to declare war upon slavery. Or, as an editorial in St. Louis’s Westliche Post put it as Lyon marched across Missouri, “The more one encourages slaves to escape from the South, the more one weakens the rebellion and the sooner one defeats it.” Emancipation, in this view, was not simply a goal of the war, and still less a possible outcome to be repeatedly disavowed in favor of an exclusive focus on the question of “union.” Revolutionary alliance with runaway slaves was a strategic imperative. It would take Abraham Lincoln and his eastern generals another year to absorb the lessons of Lyon’s campaign. By then, Lyon would be dead, the first Union field-grade officer to die in battle in the Civil War.35

Lyon first marched on Jefferson City, the state capital. Finding that Jackson and Price had left the city and traveled west on the Missouri River, Lyon left Boernstein in control of the capital and continued westward. Boernstein found the city a ruin—most city officers had fled with the governor. “Everything would have to be recreated, if the usual course of bourgeois life was not to be interrupted,” he later wrote. Boernstein, the onetime radical turned ally of Benton and Blair, stuck close to the orthodox distinction between a war to preserve the union and a war to abolish slavery in a handbill he had printed and distributed throughout the city. “Your personal security will be Guaranteed. Your property will be respected; your slave property will not be touched by any part of my command, nor shall any slave be allowed to come to my lines without written permission from his master… at the same time I shall not tolerate the slightest attempt to destroy the union and its government.” Boernstein had hoped to pacify the population of the city by guaranteeing their property and promising not to interfere with their slaves, but he soon found that these assurances did him little good. The residents of the city tore up his proclamation and used it to litter the streets. Those who had slaves ran them off to counties out of the reach of the Union Army. Boernstein, feeling isolated and undermanned, finally resorted to simply jailing five of those whom he took to be his most fervent antagonists for crimes no greater than flying the Confederate flag. Under the pressure of events, Boernstein’s liberalism quickly collapsed into its opposite.36

Along Lyon’s westward march, the army made another kind of history—no less violent, to be sure, than its military actions, but a history in which the violent exercise of authority was fitfully but significantly aligned with the cause of human emancipation rather than simply with that of national preservation. As Lyon’s army marched west it relied on runaways for information about their owners, the landscape, and the whereabouts of pro-Confederate troops in the field. At Boonville, German Home Guards who had joined the federal forces armed three fugitives and fought beside them in the trenches. After their defeat near Springfield and Lyon’s death, the federal force, now under the command of Franz Sigel, retreated to Rolla, where their encampment became a magnet for escaping slaves from south-central Missouri. Many of those who made it to the encampment at Rolla were given uniforms and put to work in support of the army. In Rolla, at least, emancipation was less a disputed aspiration of the war effort than a means of its practical prosecution.37

Fall turned to winter, and escaped slaves—self-emancipated African Americans—continued to make their way to the Union camp at Rolla, part of an uprising across the South that W.E.B. Du Bois termed “the General Strike”—the mass withdrawal of the laboring class of the South. The emerging policy of the government in Washington was to treat them as “contraband”—the property of disloyal owners that might be confiscated like any other property. But they did not act like property: these Black Americans told their stories, denounced their erstwhile owners as traitors, and offered their labor and even their lives. They put on the uniforms and took up the arms provided them by the army. In the camp in Rolla, Sigel finally met the flesh-and-blood frontline soldiers of the revolutionary war against property he had imagined in his notebooks.38

The politics of the camp in Rolla—the combination of the political radicalism of Sigel and the revolutionary action of the African Americans who joined his army—came for a brief moment to define the approach of the entire US Army Department of the West, still headquartered in St. Louis but now under the leadership of John C. Frémont. In St. Louis, Frémont surrounded himself with European revolutionaries. He moved through the city with an armed guard of 150 mounted men, headed by the Hungarian Charles Zagonyi (Károly Zágonyi); they wore uniforms a shade darker than Union Army blue, with distinctive plumed hats, and carried German-made pistols. Another Hungarian, Alexander Asboth (Asbóth Sándor), was Frémont’s chief of staff until he was sent to Rolla to replace Sigel; there he continued to embrace fugitives from slavery with the same revolutionary pragmatism demonstrated by his predecessor. For many Germans in St. Louis, Frémont represented not simply a military commander whom they could respect and trust, but one whose appointment reflected their own devotion to the cause. “Will not everyone reach for his sword with courage and enthusiasm when he knows a Frémont is within our walls?” asked the Anzeiger in August 1861.39

Perhaps the most interesting member of Frémont’s staff in St. Louis was Joseph Weydemeyer, whose arrival in the United States in 1851 has plausibly been called “the beginning of the history of American Marxism.” Weydemeyer, whose politics had led him to resign his position as an artillery officer in the Prussian Army in 1842, had been a collaborator and close friend of both Marx and Engels since the mid-1840s, and he had spent the years immediately after the 1848 revolution underground in Europe, editing a series of radical newspapers in which he published their (illegal) writings, including Marx’s The German Ideology and Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England. As the authorities closed in, Weydemeyer fled to New York, arriving in November 1851. In New York, he founded Die Revolution, the original publisher of Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire, which was not published in Europe until 1869. During the 1850s, Weydemeyer moved between Milwaukee, Chicago, and New York, contributing to and editing a succession of radical German-language newspapers and acting as a de facto literary agent for Marx and Engels, whose writings he helped to place in papers throughout the United States (and whose frequent and affectionate correspondence provides the best means of tracking Weydemeyer’s movements during these years—Weydemeyer was Zeppo, the least remembered of the Marx Brothers, to Marx and Engels’s Groucho and Harpo). Much of his time was spent organizing for the Proletarian League, the first Marxist organization in the United States, and the Communist Club, which was committed to “the abolition of private ownership of the means of production” and “the equality of all human beings, irrespective of color or sex.” In an 1860 letter to the German socialist Ferdinand Lassalle, Marx referred to Weydemeyer as “one of our best people” in the United States.40

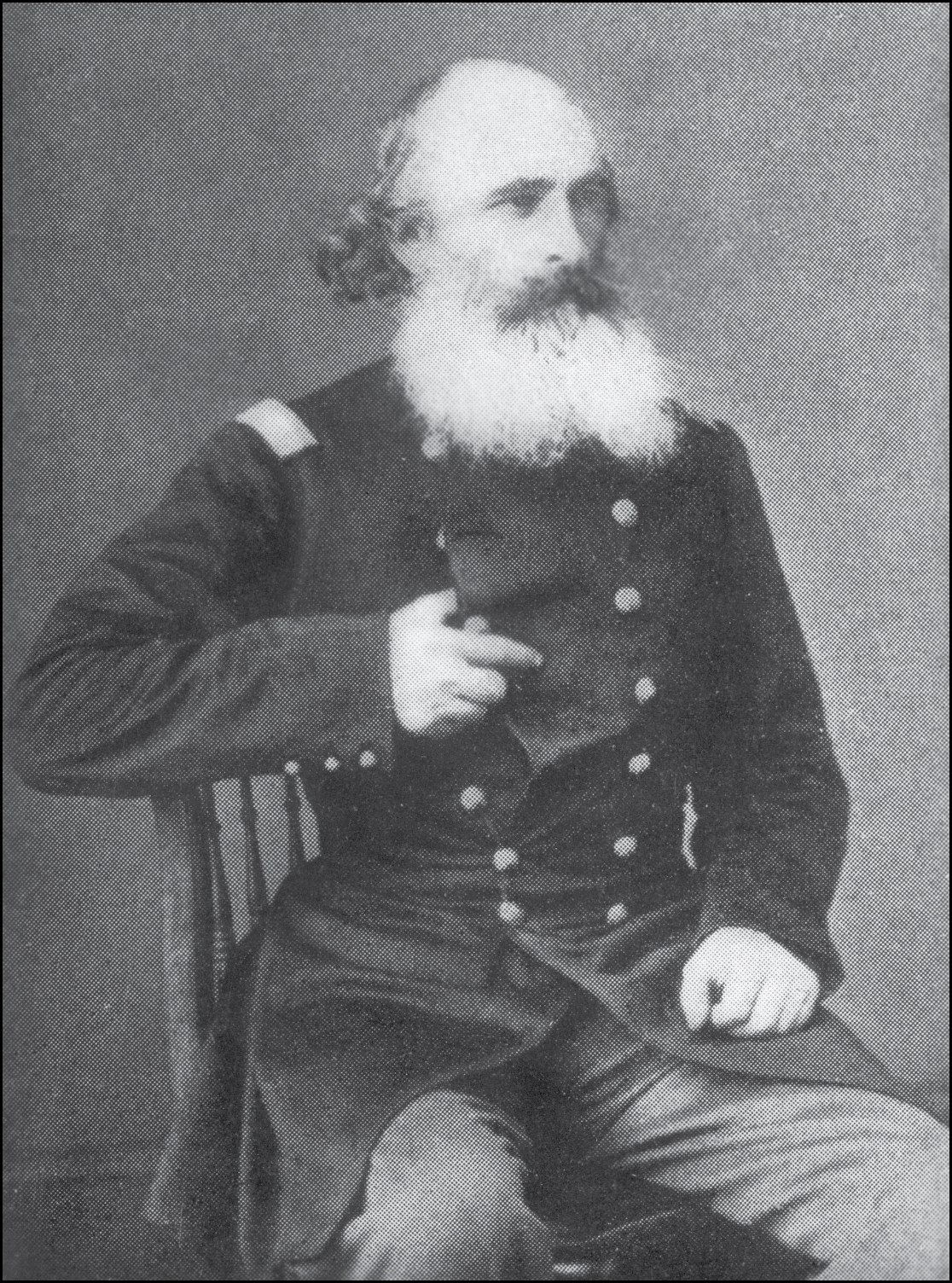

Joseph Weydemeyer was the most prominent communist in the United States at the time of the Civil War. Friend and frequent correspondent of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, he was a colonel in the US Army and oversaw the wartime fortification of the city of St. Louis. (Library of Congress)

Among the communists, Weydemeyer stood out for his insistence that the condition of the white working class could not be addressed separately from the question of slavery. Weydemeyer’s materialist Marxism convinced him that the abolition of private property and the “dictatorship of the proletariat” (the idea itself is a theoretical innovation in the history of Marxism for which Weydemeyer is sometimes credited) could not occur until capitalist industrial development had reached its apogee. For him, slavery was an economic drag on that development, and it was only with the abolition of slavery that all labor might be truly free. At the time of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, he urged his followers not to adopt the narrow position of the white supremacist free-soilers, but rather to “protest most emphatically against both Black and white slavery.” Where Bentonite liberals like Boernstein favored distributing the public domain to working people on the basis of individually held parcels of private property, Weydemeyer advocated state ownership and “large-scale agriculture” under the direction of “workers’ associations.” Whatever its virtues, it should be noted that this too was a solution that subordinated any consideration of Native American sovereignty, humanity, and ultimately survival to the “march of progress.” With the outbreak of the war, Weydemeyer enlisted and requested a posting to Missouri, which he considered the strategic key to a Union victory. In St. Louis, he joined Frémont’s staff and was assigned the task of coordinating the deployment of artillery and the construction of forts in defense of the city of St. Louis.41

On August 28, Frémont called Sigel to St. Louis for a meeting with the rest of his general staff, including Weydemeyer. Two days later, Frémont followed Lincoln’s lead in Maryland by placing Missouri under martial law. But he also went beyond the action the president had taken in Maryland by declaring that any civilian found to have taken up arms against the United States would be tried by a military court and executed if convicted. And then he did something revolutionary. On August 30, General Frémont issued an order emancipating the slaves of disloyal owners in Missouri, adopting the views of the communists Sigel and Weydemeyer, legalizing the situation on the ground in Rolla, and putting the force of the US Army behind the revolutionary actions of escaping slaves.

The response in the German papers in St. Louis was immediate and enthusiastic. The Anzeiger des Westens noted that Frémont’s action drastically exceeded his legal authority, but praised it nevertheless: “This goes quite a bit further than the confiscation law of Congress—it is a measure of war and extreme necessity. In other words it is a dictatorial act, an act à la Jackson.” It soon became clear that Lincoln (and his local proxy, Blair) had been blindsided by Frémont’s order and would not allow it to stand. But the Anzeiger stuck by Frémont, unfavorably contrasting the actions of Lincoln’s chief of staff, the Democrat George C. McClellan, “who orders escaped slaves held and returned to their masters,” to their hero Frémont, “who issues manumission out of hand to slaves.” In conclusion, the editorial implied—threatened, really—that Germans in St. Louis would stop supporting the Union war effort if Frémont was removed from his command. When Blair used the pages of the Missouri Republican to make the administration’s case, criticizing Frémont and his emancipation order for alienating the conditional unionists who were the focus of Lincoln’s effort to hold the border states in the Union, Frémont closed down the paper and threw Blair, who was a US congressman and general in the US Army as well as a friend of the president, into jail.42

Lincoln’s response was immediate. Writing to Frémont, he noted that the military trial and execution of Confederate prisoners of war would surely be met with immediate retaliation against Union prisoners of war. He then noted that Frémont’s emancipation provision “will alarm our Southern Union friends” and asked Frémont to modify his order to match the Confiscation Act, which treated self-emancipated people as “contraband of war”—as confiscated property temporarily held (a position that the Westliche Post had termed the “nonsensical contraband-fiction” two months before). When Frémont refused, insisting that if Lincoln wanted to countermand the emancipation order, he should do so publicly, Lincoln immediately obliged.43

By the beginning of November 1861, Frémont had been relieved of his command—an act that was accompanied by a genuine fear that German troops in St. Louis would mutiny when they heard the news. He was called to Washington to stand trial for the misappropriation of military funds, a charge of which he was eventually acquitted. The general was given another command (in the Shenandoah Valley, where he spent the rest of the war being outmaneuvered by Stonewall Jackson). But he remained guilty of fighting the wrong war in Lincoln’s eyes (and in the eyes of historians who have, by and large, adopted the president’s pragmatic moderation as their own moral center and treated Frémont’s emancipation as an outlying footnote to the real story)—of fighting against slavery and property when he should simply have been fighting for the United States of America and for union. Jessie Benton, Frémont’s wife, remembered that when she met Lincoln shortly after the president had rescinded her husband’s emancipation order, the “Great Emancipator” was livid about the matter and declared to her: “It was a war for a great national idea.… General Frémont should never have dragged the Negro into it.”44

In St. Louis, however, Frémont remained a hero to many and was presented with a ceremonial sword upon his return to the city after being relieved of his command. In December 1861, the Anzeiger invoked the general’s name and the example of his forces in the field in demanding that Lincoln reverse course and emancipate the slaves: “When we use the word emancipation we are not thinking of something that would have to wait until the conclusion of the peace but rather of emancipation on the basis of martial law, as Frémont tried to do.” At least 15,000 Missouri slaves had “run away to freedom,” the paper estimated, predicting that, no matter how the Lincoln administration worked to preserve it, slavery in Missouri could not last another year. Indeed, as well as the example of Frémont, the Anzeiger invoked the example of Sigel and Rolla: “Wherever we occupy them [slaveholders] an active war party in our favor must be created.… But since only the slaves are available to do the work, then it is necessary to train a proper number of them in weapons.”45

The man Lincoln appointed to replace Frémont, a lawyer, translator, and author of a book on strategy entitled Elements of Military Art and Science, was as deliberate as Frémont was rash, as studious as Frémont was vainglorious. He was also a man who adjudged Franz Sigel to be “unworthy of the rank he now holds.” Like Frémont and Lyon, General Henry Halleck had served in California. He had, indeed, been called upon to try to establish military order in the state in the aftermath of Lyon’s well-publicized atrocities against the Pomo. In November 1847, Halleck placed the state of California under martial law and instituted a statewide pass system to lock down the new territory’s Indian population. The system required California Indians either to be employed by non-Indians or to be defined as “thieves and marauders”—designations that rendered them vulnerable to (officially sanctioned) massacre. “Any Indian found beyond the limits of the town or rancho in which he may be employed,” it read in part, “without such certificate or pass, will be liable to arrest as a horse thief.” Drawing upon the disciplinary repertoire of the slaveholding South, the order effectively legalized the enslavement of California Indians.46

In St. Louis, Halleck struggled to reassert the officially authorized and legalistic account of the war as a struggle for the Union rather than against slavery and property: “Military officers cannot decide about the rights of property,” he declared. As for the small-scale revolution that was occurring in Rolla, Halleck instructed officers there to stop admitting Blacks into their lines.

For the moment, Lincoln remained more interested in shoring up his standing with border-state Unionists than he was in emancipating the slaves. But the enslaved continued to escape and to present themselves as human dilemmas to the officers in Rolla: What about this family who will otherwise starve? What about this woman who has been cooking for the troops and doing their laundry? What about this man with a disloyal master? What about this woman who gave us information about the movements of the proslavery guerrillas? What about men who were willing to take up arms and risk their lives alongside white soldiers in the brutal guerrilla war unfolding along the border with Kansas? As the Anzeiger editorialized in December 1861, Halleck’s orders notwithstanding, slavery in Missouri was “disintegrating” under the pressure of strategic alliance between radical soldiers and rebellious slaves.47

Even after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the Anzeiger editorialized that Lincoln and his supporters had “gone as far toward the abolition of slavery as ink, pens, and paper would let them,” but that it would take men like Frémont and Sigel to really do something about it. In the summer of 1863, radical Germans in St. Louis used the anniversary of the march on Camp Jackson to demand the removal of General Halleck, whom they thought insufficiently committed to emancipation. Frémont and Sigel, however, were fulsomely praised by speaker after speaker that day. In 1864, the St. Louis Germans were among the principal supporters of Frémont’s brief presidential candidacy as the nominee of the Radical Democracy Party on a platform committed to emancipation, equal rights for Blacks, and the confiscation of Confederate property, and Frémont was also supported by the abolitionists Frederick Douglass, Wendell Phillips, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.48

And yet, in the coming years, it was the ghost of Thomas Hart Benton that would haunt the city of St. Louis. The national government emerged from the war pledged to the white settlers and railroads at the heart of the Bentonite vision, and it began a decades-long campaign of military pacification, ethnic cleansing, and, finally, annihilation in the West. The apotheosis of the Bentonite vision for the city represented a triumph for Frank Blair, Gratz Brown, and Henry Boernstein over Franz Sigel, John Frémont, and Joseph Weydemeyer, as well as over Basil Duke, Claiborne Jackson, and Sterling Price. But on the streets of St. Louis, as both Black and white migrants crowded into the city, the question of freedom remained an open and contested one. And indeed, at the end of the period of Reconstruction, radicals in St. Louis would once again provide the nation with an example of Midwest-style communist revolution.