5 | BLACK RECONSTRUCTION AND THE COUNTERREVOLUTION OF PROPERTY

God wept; but that mattered little in an unbelieving age; what mattered most was that the world wept and still is weeping and blind with tears and blood. For there began to arise in America in 1876 a new capitalism and a new enslavement of labor… united in exploitation of white, yellow, brown, and Black labor, in lesser lands and “breeds without the law.”

—W.E.B. DU BOIS, Black Reconstruction in America

SOMETIMES WHEN PEOPLE WHO LIVE IN ST. LOUIS TODAY TRY to explain the racial inequality they see in the city around them, they rely on the fact that “there was no Reconstruction in Missouri.” Unlike the slaveholding states of the Deep South, Missouri was not placed under federal military occupation after the war; nor was the state, which had never officially seceded from the Union, required, like the slaveholding states farther to the south, required to ratify the Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution in order to reenter the Union. And yet, in many ways, it was the state of Missouri in general and the city of St. Louis that epitomized both the most radical version of “abolition democracy” in the aftermath of the war (especially the General Strike of 1877) and the pitiless and cynical triumph of capitalism and imperialism—the counterrevolution of property—in the growth of the “liberal” wing of the Republican Party out of the state’s Bentonite legacy.1

Although many secessionists had left the city in the days immediately following the surrender of Camp Jackson, and more continued to leave throughout the war, St. Louis was a fiercely divided city for the duration of the war. The city and county had been placed under martial law by Frémont on August 14, 1861 (the order was extended to the rest of the state at the end of the month) and were governed throughout the war from the office of the army provost marshal. Residents of the city were required to be off the streets by 9:00 p.m., and those who crossed into or out of the city or the county were required to carry a written pass that could only be obtained after they swore an oath of allegiance to the United States. Newspapers critical or even insufficiently supportive of the United States of America, the Union Army, or its various offices in St. Louis could be suppressed (as, indeed, was the St. Louis Republican). And individuals who spoke intemperately in public—yelling “Hurrah for Jeff. Davis” at a passing column of Union troops, for example—could be imprisoned (as was Frank Blair). Under General Halleck, martial law in St. Louis only intensified. All state and local governmental officials, attorneys, jurors, university officials, and voters were required to swear the oath of allegiance—a requirement that was eventually included in the wartime Missouri State Constitution. Exhibiting the Confederate flag in the city of St. Louis was punishable by imprisonment. And as elsewhere in the United States, the property of traitors was subject to confiscation.2

Although Maryland was the first state that Lincoln placed under martial law (and the state that produced the emblematic struggle over the right of habeas corpus during wartime, Ex parte Merryman), it was Missouri where the suspension of civil law had the deepest effect upon the population and everyday life. Almost half of all trials of civilians by military commission during the Civil War occurred in Missouri—close to five thousand in all, and one for every three hundred males in the state. In St. Louis, the provost marshal struggled to find enough space in the city to house all the prisoners. The McDowell Medical College on Gratiot Street was turned into a prison that held as many as two thousand inmates. Prisoners from St. Louis were sent across the river to Alton, Illinois, where as many as five thousand were eventually incarcerated in a facility with 256 cells. Most famously, prisoners were held in the Myrtle Street Prison, the converted slave pen of the St. Louis trader Bernard Lynch. Outside, Union soldiers sang “John Brown’s Body” as they marched by in the street.3

Meanwhile, as Grant moved down the Mississippi in the campaign that culminated in the Union victory at Vicksburg in July 1863, St. Louis once again became a city of refugees. The antislavery minister Galusha Anderson recorded the stories of some of the self-emancipated people who made their way to St. Louis. “The contrabands usually trudged into the city in groups, bearing in their hands or on their shoulders budgets, filled with old clothing or useless traps, their heads covered with dilapidated hats or caps, or, in the case of the women, wrapped about with red bandanas. Their garments were coarse, often tattered, and usually quite insufficient to shield them against the cold of winter.” Some, he remembered, came barefoot, their feet frostbitten and bleeding from the frozen road, their shoes in some cases having been seized by bands of white irregulars they met on the road; others had had their shoes confiscated for the night by owners who thought it would keep them from leaving. “St. Louis was for them,” Anderson wrote, “a city of refuge.” Between 1860 and 1870, the Black population of the city of St. Louis increased by 600 percent. Although Blacks made up a higher proportion of the population of many cities in the United States by 1880, only Philadelphia and Baltimore had larger Black populations when measured in absolute terms.4

The congregation of Blacks in St. Louis was a revolutionary challenge to the notion of it as the imperial capital of the “white man’s country” of the West. From the time of the War of 1812, the bedrock racial policy that governed the city of St. Louis had been whites-only settlerism. The broad consensus shared by both Free Soil Republicans and the proslavery Democrats who supported the Dred Scott decision was that there was no place in St. Louis (nor really in the United States of America) for free Black people. And yet, during the war, they came to the city by the thousands. They set up mutual aid societies and schools, they organized in neighborhood watches for self-defense, and they raised money to feed and clothe their neighbors. They went to the office of the provost marshal and swore out complaints when their white employers refused them wages, or beat them, or tried to rape them or their children. Black workers, mostly women, insisted that the conditions under which they worked were a matter of federal concern and demanded an end to white impunity, to the world in which the “Negro has no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Sometimes the soldiers intervened, many other times they did not, but gradually the freed people made a larger point: you white men must respect the fact that we have rights. The nature and limits of Black freedom remained uncertain and fiercely contested—indeed, they still are today—but the days of Scott v. Sandford were gone, for the moment at least.5

The strategic and symbolic center of Black freedom in Civil War St. Louis was Benton Barracks, in North St. Louis, on the site of present-day Fairgrounds Park. Benton Barracks was established by John C. Frémont in 1861 and overseen by William Tecumseh Sherman (in his first command as a general officer) and Benjamin Bonneville over the course of the war. Originally intended as an intake and training base for the US Army Department of the West, Benton Barracks gradually grew into a combination military base and hospital, prisoner-of-war camp, and refugee camp. By the end of the war, the military barracks alone could house thirty thousand soldiers, somewhere between one-fifth and one-sixth of the resident population of the city, and the site was jointly administered by the army; the federal Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands; and the Western Sanitary Commission (founded in St. Louis in 1861 to aid in the support of escaping slaves). The first regiments of US Colored Troops—the Sixty-Second, Sixty-Fifth, and Sixty-Seventh US Infantry—were formed at Benton Barracks in May 1863, months before the formation of Black regiments elsewhere. By the end of the war, over eight thousand Black men from Missouri, a full 40 percent of the Black men of military age in the state, had enlisted in the US Army and gone into battle singing “Give Us a Flag”:

Oh, Frémont he told them when the war it first begun,

How to save the Union and the way it should be done.

But Kentucky swore so hard and Old Abe he had his fears,

Till ev’ry hope was lost but the colored volunteers.

By the time the Missouri State Constitution of 1865 made their legal emancipation official and irrevocable, most of those who had been enslaved in St. Louis had long since claimed freedom for themselves.6

Black volunteers—formerly enslaved—from all over the western theater went to Benton Barracks for training. There they were provided (by the Western Sanitary Commission, overseen by William Greenleaf Eliot) with copies of Sargent’s Standards Primer and taught to read. Black women, meanwhile, were trained as nurses and eventually oversaw a military hospital for Black soldiers set up on the grounds in 1864. Black soldiers, together with paroled Confederate prisoners of war, guarded the camp and the largest military hospital in the West, built to accommodate 2,500 patients at a time. By the end of the war, Benton Barracks furnished the city of St. Louis, as well as the nation as a whole, with an example of Black capacity-building, self-care, and self-determination. Some of the most prominent Black political figures of the postwar period spent time there. Hiram Revels, who recruited an entire regiment of Black soldiers in St. Louis during the war, was the first African American elected to the US Senate (from Mississippi) during Reconstruction, and Blanche K. Bruce, elected to the Senate (also from Mississippi) shortly after Revels, also spent time at Benton Barracks during the war. Although it would be a mistake to overstate the democratic significance of what was, after all, an armed camp that was segregated and rampantly overcrowded, subject to periodic epidemics, and ruled in the final instance by open force, it is nevertheless the case that the soldiers and scholars, the nurses and teachers, the refugees and the ruined, mendicant beggars, represented a collective challenge to the half-century-long hegemony of the “white man’s country.”7

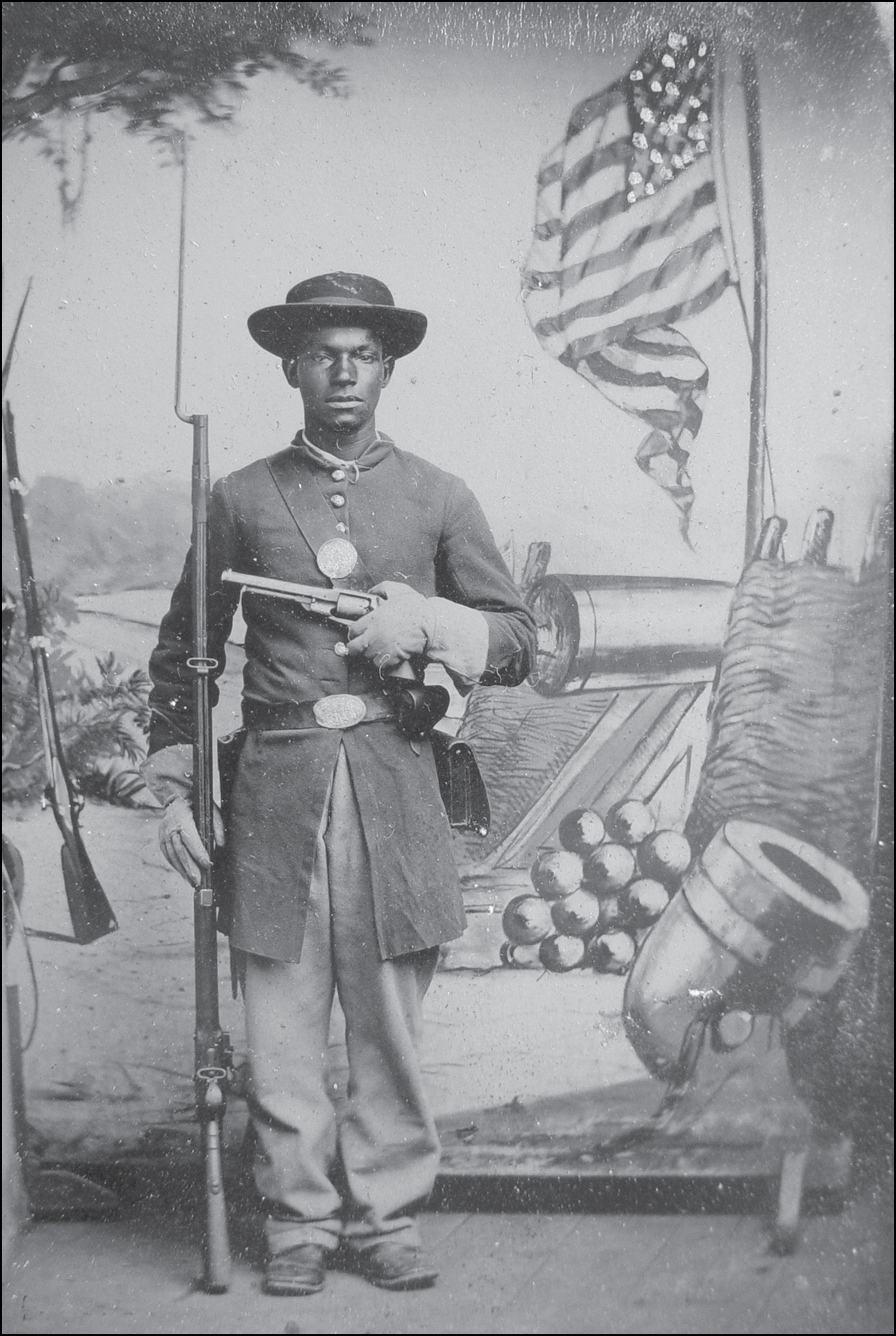

This African American soldier was one of the thousands who enlisted and served at Benton Barracks (on the site of today’s Fairgrounds Park) during the Civil War. After the war, Black soldiers from St. Louis were deployed to protect white settlers in the West. (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam)

Public conveyances, especially streetcars, were other defining sites of Black struggle in St. Louis. During the war, Blacks were banned from the inside of the cars, allowed only to ride exposed on open balconies at the front of the cars. “I have seen neatly dressed colored females on cold days stand on the front platform with tender infants in their arms,” wrote one sympathetic observer. For the Black citizens of St. Louis, who rode outside in the rain and freezing winter, this was an issue as important as any other, although it was generally treated as a distraction by the “radical” Republicans, who thought Blacks should focus on the struggle for suffrage (in order to become loyal supporters of the Republican Party). Beginning in 1865, Blacks on streetcars began to push their way inside, and in 1868 they won a judgment in circuit court allowing them to ride inside the covered cars.8

In response, the Anzeiger, which quickly abandoned its radicalism in the years after the war, joined the Democratic (that is, white supremacist) St. Louis Republican in editorializing against the integration of hotels, ballrooms, and so on, in the city. In essence their argument was that public accommodations were private property and that property should be exempted from the struggle for social equality: “according to the terms of the federal Constitution today every proprietor of an omnibus, hotel, concert hall or ball room is permitted to decide himself who he will admit and who not.” The party of property had survived the war and emancipation; it was only a matter of time before it regained its footing.9

Black activists were able to gain a slightly larger degree of white support in their struggle for public education. Black educators in St. Louis had been running underground schools for decades, and in defiance of an 1847 state law that forbade teaching Blacks to read. During the war, Black veterans and local Black activists had built “freedom schools” where children and adults alike could learn to read and reckon. Under the state constitution of 1865, the Missouri General Assembly was empowered to establish public schools “for the children of African descent.” The privileges of white supremacy and property were entwined in the bilious response of the St. Louis Republican to the supporters of (segregated) public schools for Blacks: “If they like to associate with the n—rdom, as would seem to be the case, let them go to [school with Blacks], but not at the expense of white men.” The fact that Black St. Louisans had long been paying taxes to support schools they were not allowed to attend did not receive a hearing in the pages of the Republican.10

In 1866, the St. Louis School District opened three public schools for Black children, including Toussaint L’Ouverture Elementary School, the alma mater of both US poet laureate Maya Angelou and St. Louis activist Percy Green. In 1875, the city’s Sumner High School became the first public high school for Black students west of the Mississippi River. And the Black veterans of the fight for public schools—men like James Milton Turner, who had served General Lyon as a personal attendant and would go on to be appointed ambassador to Liberia, and future senator Blanche K. Bruce, who had been a schoolteacher and steamboat porter along the Mississippi—led the way in founding, at a meeting held in St. Louis in October 1865, the Missouri Equal Rights League, which became the principal Black organization fighting for suffrage in Missouri. “Had it not been for the Negro schools and colleges,” W.E.B. Du Bois later wrote, “the Negro would to all intents and purposes, have been driven back to slavery.”11

Along with the Black refugees to the city during the war came tens of thousands of whites. Galusha Anderson remembered them as coming in even greater numbers than the Black migrants, and as equal in their poverty. “They entered St. Louis in rags, often hatless and shoeless, sallow, lean, half-starved, and unkempt. Very many of them were women and children, in pitiable plight, half-naked, shivering, penniless, dispirited,” he wrote. Anderson found them, on the whole, unwilling to work and unfathomably hostile to making common cause with their Black neighbors, who were mostly refugees themselves. “They regarded manual labor as a disgrace. They had been taught in the school of slavery that honest toil was servile and ignoble,” he wrote. He went on to tell the story of visiting a white family at a federal refugee center that had been set up at the Virginia Hotel. Even though their squalid room offered a sharp contrast to the clean and “homelike” room of the Black man who lived next door, they expressed their dismay that the superintendent would put them in a room on an integrated hallway.12

Anderson held out little hope for poor white people whose imagination was bounded by the political horizon of the white republic. His disappointment suggests that he had imagined that over the course of the war white St. Louisans would gain some empathy for their Black neighbors. Their resentful statement of their own embattled entitlement—the idea that only “the dutch and the darkeys” were free in St. Louis—had embedded within it a recognition of the ways in which their own social and political condition had come to resemble that of erstwhile slaves. They had become subject to the same 9:00 p.m. curfew and pass laws that had defined the lives of slaves and free Black people in St. Louis since the 1830s and 1840s; they had been placed under surveillance and subjected to the rumors spread about them by their neighbors; and they had been deprived of their property, governed by force, and imprisoned in Bernard Lynch’s downtown slave pen. The question, in Anderson’s mind, was whether they would declare that their poverty and poor treatment were unjust because they were white, or because it was unjust for anyone to be treated that way.

Among those who did make a direct connection between the plight of the city’s poor whites and their Black neighbors was Joseph Weydemeyer, who had finished out the war as the military governor of the eastern district of Missouri, which stretched westward from St. Louis to the German settlement in Hermann. In a series of editorials published over the summer of 1866, first in German in the Westliche Post and then in English for the St. Louis Daily Press, Weydemeyer outlined a case for the limitation of the working day to eight hours as the defining struggle for the interracial (and national and eventually global) working class. “The eight-hour movement,” Weydemeyer wrote, “slings a common bond around all workingmen, awakens in them a common interest, pulls down the barriers too often raised between different trades, declares war against all party prejudices of birth and color, and thereby clears the ground for the formation of a real workingman’s party, in whose hands soon will be held the future of the country.”13

For Weydemeyer, the eight-hour movement was only a first step, a way for workers to overcome the historical, racial, and economic divisions that had undermined their solidarity: after emancipation, all workers were paid by the hour, and so it was in a struggle over the length of the working day that they might discover their commonality. When the Anzeiger mocked the “radical Germans” who would “give [the Negroes] voluntarily their most beautiful plantations; they would divide their belongings with them; they would give them all the political rights which they themselves exercise… every Teuton would instruct a Negro in German philosophy,” and seek them as marriage matches for their sons and daughters, they were thinking of Weydemeyer. Still, the communist colonel was popular enough among St. Louisans that he was elected St. Louis County auditor in 1866. But before the “radical auditor” could fulfill his promise to collect back taxes from war profiteers and reform the city’s property-friendly tax laws, he died in a late-summer outbreak of cholera.14

The struggle for Black suffrage marked an inflection point in the historical transition back from the revolutionary possibilities of wartime toward the whites-only pro-property liberalism that determined the political vision of Boernstein, Brown, and Benton. At the state constitutional convention in 1865, there was a good deal of support for Black suffrage expressed by radicals, and especially by Germans from the city of St. Louis and by the vice president of the constitutional convention, Charles Drake, who exerted so much influence over the proceeding that the result came to be known as “the Drake Constitution.” And yet, from the beginning, there was an audible backbeat of white fear: If Missouri allowed Blacks to vote, wouldn’t the state become a magnet for cheap labor in the shape of emancipated slaves? Why should Black men be allowed to vote immediately when immigrants were required to wait a year before naturalization? Why should Black men be allowed to vote when white women were not? And finally, most pertinently and destructively, why should Black men vote when former Confederates could not?

Even among the radicals, there was little hope of getting the state of Missouri to produce a constitution that would allow African Americans to vote. In 1865, the voters of the state approved a new constitution that limited suffrage to “every white male citizen of the United States” and “every white male person of foreign birth who may have declared his intention to become a citizen.” The constitution extended the privileges of whiteness to immigrants, while denying citizenship to Blacks—it extended the mantle of whiteness to the Germans, chiseling off the liberals who were willing to abandon common cause with former slaves from the radicals. African Americans in Missouri—or, more properly, African American men in Missouri—would not gain the right to vote until the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.15

Having failed in their effort to broaden their political base, the “radicals” had instead focused on narrowing the political base of their opponents (read: former Confederates). The result was the so-called Iron-Clad Oath, or Test Oath, the various provisions of which accounted for thirteen of the constitution’s twenty-six articles concerning suffrage, including a page-long itemization of eighty-one ways in which a prospective voter might have demonstrated “sympathy” for the Confederacy. Those who wished to vote or hold office in Missouri were required under the constitution to swear that they had “always been truly and loyally on the side of the United States against all enemies thereof.” Under the Missouri Constitution of 1865, the politics of the state came to be preoccupied with questions about white life, white politics, white rights, and white reconciliation in a way that foreshadowed the course of Reconstruction nationally. Indeed, St. Louis, the politics of Missouri, and the struggle over the Test Oath produced the political leadership that pointed the Republican Party and the nation toward the end of Reconstruction and the demise of the federal effort to guarantee the constitutional rights of southern Blacks.16

The position of the “liberal” opponents of the Test Oath was undergirded by a sometimes-spoken-sometimes-left-unspoken white supremacy. Even many of those who had opposed slavery before the war agreed in its aftermath that it was wrong to deny white men the right to vote. When B. Gratz Brown, now a US senator from Missouri, said in 1866, “Universal suffrage will triumph in the end,” he was defending the rights of ex-Confederates in Missouri to vote, not ex-slaves. Brown was joined in the struggle for the rights of whites by Carl Schurz, who soon became the most famous German inhabitant of St. Louis, succeeding Sigel as surely as Marx argued that comedy succeeded tragedy in the Eighteenth Brumaire. Tall, thin, bearded, and bookish, Schurz had been a Prussian student radical who took up arms in 1848. With the collapse of the revolution, he went into exile in Switzerland in 1849. The following year, he returned to Prussia, where he collaborated with a sympathetic guard to rescue his onetime professor and radical mentor, Gottfried Kinkel, from the notorious Spandau Prison—an act that gained Schurz international acclaim among radicals. By 1851, he was in London, where he met the exiled revolutionaries Louis Kossuth (Kossuth Lajos), Giuseppe Mazzini, and Karl Marx. He moved to the United States in 1852. By the time of the Civil War, Schurz had become a well-known Republican orator, a fierce opponent of slavery, and an enthusiastic supporter of “free labor.” In the American context, however, Schurz was no revolutionary. He was an unapologetic skeptic about the abilities and capacities of the Black people about whom he so regularly spoke. After the war, he settled in St. Louis, where he was hired by Joseph Pulitzer to edit the German-language Westliche Post.17

With the collapse of the Confederacy and the end of slavery, radicals like Drake, who had supported emancipation beginning in 1861 and presided over the Confederate-disenfranchising constitutional convention of 1865, and liberals like Schurz could no longer find common ground. The politics of the national Republican Party increasingly divided those for whom the struggle for “freedom” was predicated on the promotion and protection of African American voting rights (not to mention the more thoroughgoing human emancipation imagined by Sigel or Weydemeyer) from those for whom “freedom” meant the freedom to own property and to go on doing whatever they were doing without having to bother about other people’s rights. The latter sort came to be called “liberals,” and Carl Schurz became a leading figure in the liberal wing of the Republican Party, first in Missouri and, soon after, nationally. For Schurz, association with radicals—and thus with Blacks—drew unnecessary attention to the history of German radicalism and divided them from the mainstream of the Republican Party. Asked again in 1868 to support voting rights for Blacks, Germans joined the rest of the city in voting two-to-one for white supremacy. The Republican Party was leaving African Americans behind, and the St. Louis Germans were becoming white.18

In the meantime, the Bentonite center of gravity in Missouri politics reconstructed itself around the question of the voting rights of former Confederates. Schurz and the railroad Republican Gratz Brown were joined in the struggle against the Test Oath by Frank Blair, whose 1888 statue in Forest Park remembers him not only as “the Indomitable free-soil leader of the west,” but also as “the magnanimous statesman, who, as soon as the war was over, breasted the torrent of proscription, to restore to citizenship the disfranchised Southern people.” After the war, Blair returned to the Democratic Party as a candidate for the vice presidency in 1868. Even in the context of the Reconstruction era, Blair stood out for his willingness to suggest that Black suffrage would naturally and inevitably lead Black men to, as he put it, “subject white women to their unbridled lust.” Postwar party politics in Missouri, like prewar party politics, was thus framed almost entirely within the logic of the “white man’s country.”19

In the aftermath of the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, Brown and Schurz convened a convention of self-styled liberal Republicans in St. Louis. The initial impetus of the meeting was to work toward the final repeal of the civic disabilities of post-Confederate whites that had been written into law in the 1865 state constitution, now made even more galling to the liberals by the Fifteenth Amendment’s guarantee of Black male suffrage. But the result of the meeting was the emergence of a new movement within the Republican Party, known at first as “the Missouri Plan” but soon known as Liberal Republicanism. By 1872, Schurz and Brown had become rivals, but Liberal Republicanism had grown from a splinter tendency in Missouri politics into a national movement—and a significant challenge to both the reelection of President Ulysses S. Grant and the continued reconstruction of the South.

Liberal Republicanism was a white nationalist movement. Emblematized by the famous words of their 1872 presidential candidate, Horace Greeley—“root, hog, or die,” an animalizing and degrading translation of the commonplace directive to fend for one’s self—the Liberal approach to the freedmen was to abandon them. The question of Black freedom was to be left to the states as the federal government turned to promoting the economic development of the West and getting out of the way of capital—in other words, as it turned once again to empire. It was a political vision not so different from that of Thomas Hart Benton. Genocide was a predictable result.

The disputed presidential election of 1876 resulted in the extraconstitutional appointment (by a bipartisan backroom bargain) of the Liberal Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to the presidency. In exchange for the elevation of Hayes, the Liberal Republicans agreed to end the federal military occupation of the South, leaving the region’s Black citizens to fend for themselves against the voter-suppressing, night-riding, sharecropping, convict-leasing, and lynching of the period that historians still, outrageously, generally refer to as “Redemption.” The end of Reconstruction was a negotiated settlement between the Republicans and the Democrats that was also, in effect, a bargain between capitalism and white supremacy. In return for southern Democratic support for the railroad and tariff, the Republicans would abandon their commitment to Reconstruction and the federal protection of Black freedom. It was an agreement that reflected the final triumph of the Missouri (or Liberal) tendency in the Republican Party—a victory effectively announced to the nation days later when Hayes appointed Carl Schurz to be his secretary of the interior.20

For Du Bois, Reconstruction had represented a potentially revolutionary alliance of poor whites and newly emancipated Blacks—an alliance of precisely the sort forecast in the camp at Rolla and celebrated by Weydemeyer in the pages of the Westliche Poste. Correspondingly, the end of Reconstruction represented not simply the unleashing of white supremacy on the South, although that was surely part of it, but also the alliance of white supremacy with property, for as both the most radical and most conservative among nineteenth-century observers noted, the right to hold human property might have been the first to be challenged, but there was no necessary reason that it should be the last. It was, then, no accident that the counterrevolution of property had its earliest political precursors in the politics of Missouri, where the most radical wartime critique of both slavery and the rights of property more generally had taken root. Nor perhaps was it an accident that it resulted in the meteoric rise of Carl Schurz, a German liberal from Missouri. Nor, indeed, was it an accident that Schurz became the secretary of the interior—the man with the final say about the disposition of federal lands and policy toward western Indians, the Bentonite legacy of the “white man’s country.”

In St. Louis, the intellectual and political heirs of Sigel and Weydemeyer mounted a final battle. The St. Louis General Strike of 1877 provided the nation with the era’s most compelling example of interracial radicalism—a final flash-lit image of the fading promise of abolition democracy. In July of that year, railway workers on the Baltimore and Ohio went on strike in Martinsburg, West Virginia, protesting long-standing grievances about dangerous working conditions, wage cuts, speedups, and union-busting blacklisting. The strike spread along the rail lines: to Louisville, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Chicago; to Kansas City, Omaha, and as far west as San Francisco. In several cities, including Pittsburgh and Chicago, there were violent clashes between police and state militia forces called up to clear the tracks and strikers intent on shutting them down. And in several others, the radical Workingmen’s Party, a largely immigrant group composed of socialists and Marxists, took center stage—nowhere more so than in St. Louis.21

On the afternoon of July 22, railroad workers gathered in the rail yards in East St. Louis for a rally in support of the strike. Their speeches decried the way “capitalists” treated “the workingman” and compared the condition of railroad workers to that of serfs and slaves. “Brother slaves!” one speaker addressed the crowd, “Yes, brother slaves. We are also serfs if we continue to work on the present reduction of wages on which we can barely live.” It was not long before the radicals of the Workingmen’s Party marched in, to raucous cheers. Five hundred strong, divided into German, Bohemian, French, and English sections, singing “La Marseillaise” and waving the red flag of revolution, they urged the railway workers to shut down the lines and take to the streets. One by one, the rail workers’ unions voted to go out, and the strike was scheduled to begin at midnight on July 23.22

On the night of the twenty-third, the Workingmen’s Party staged a massive rally at Lucas Market in downtown St. Louis. Speakers urged the strikers to be ready to fight when the military intervened on the side of the railways. “We have now a worse time than the slaves had in the 1850s,” one of the speakers told the crowd. “If it must be by arms, let it be by arms.” The assembly elected a committee to visit the mayor of St. Louis and apprise him of their determination to support the striking railway workers. Among the five elected was a Black man who was remembered by onlookers only as “Wilson.” The Workingmen’s Party, which had theretofore resisted any call to try to organize Black workers, was being led by the exigency of the moment and the logic of its own rhetoric toward a revolutionary alliance with the Black workers of St. Louis. Representatives of the party began to go door to door in the city, urging workers to strike in support of the railway workers; in shop after shop, they did.23

The next day, July 24, three hundred soldiers from the Twenty-Third Infantry and two Gatling guns arrived in St. Louis. They were commanded by Jefferson C. Davis (no relation), who had just finished a tour fighting the punitive, genocidal Modoc War in California. His presence in St. Louis exemplified the generalization of imperial violence in the service of capitalism and racial order that has repeatedly occurred in American history: machine-gunning the Modoc Indians in California made it that much easier to imagine doing the same in St. Louis. Davis was notorious in the army for having murdered a superior officer during the Civil War (General Halleck, by that time in charge of all of Lincoln’s armies, had deemed a trial inexpedient due to a shortage of competent officers) and for having abandoned a large number of escaping slaves to a murderous Confederate cavalry charge, for which he had been briefly suspended from command.24

On the night of July 24, an estimated ten thousand workers rallied at Lucas Market. They cheered speakers who urged them toward an armed conflict with the federal force and stoked their willingness to “die in the struggle.” “Negroes, too?” someone shouted from the crowd, and the crowd shouted “Yes!” A Black stevedore was called onto the stage, and he spoke to the crowd about the specific condition of Black workers on the levee—starvation wages in the summer and unemployment in the winter, when the river trade slowed. He then challenged the crowd: “Will you stand for us regardless of color?” “We will! We will!” they shouted back. The leaders of the Workingmen’s Party then organized the crowd into patrol companies to prepare for street battles against the police and the military and to “protect property.” At the end of the night, the crowd voted to declare a general strike, demanding the enforcement of an eight-hour day in all branches of industry and an end to child labor. Proclamations, printed in English and German, were posted throughout the city. Eleven years after his death, the emancipatory vision of Joseph Weydemeyer rose again in St. Louis.25

On July 25, 1877, the St. Louis General Strike took hold of the city. Historians have termed it the first general strike in the history of the United States, and it was clear to contemporary observers that something extraordinary was happening in St. Louis that summer. “It is wrong to call this a strike; it is a labor revolution,” wrote the Missouri Republican disapprovingly. Workers of “all colors” marched through the city carrying the tools of their trade and waving the red flags of the railway signalmen. As they marched through the streets, workers inside businesses came out to join them; they left in their wake a pathway of closed shops—foundries, flour mills, smelters, bakeries. By the end of the day, sixty factories had been shut down and the crowd was in control of the city, and nowhere more so than on the railway, where the strike had begun: the strikers had reopened the lines and begun collecting fares. Soon a flour mill was opened in order to provide bread for the strikers and the city, and businesses across the city began to reopen under the control of armed strikers and in compliance with the demand of the strikers for an eight-hour day. For a time, the city of St. Louis was governed by a workers’ collective of the sort imagined by Joseph Weydemeyer. “The cool audacity and impudent effrontery of the communists have nowhere shown so conspicuously as in St. Louis,” wrote the Chicago Tribune of the inauguration of what was soon referred to in newspapers across the nation as the “St. Louis Commune.”26

To onlookers, especially unsympathetic onlookers, the most remarkable aspect of the strike was its interracial solidarity, coolly described by a reporter from the New York Sun as “a novel feature of the times.” In St. Louis, however, the response in the mainstream media was more heated, incendiary even. “There was something blood-curdling in the manner in which they shouldered their clubs and started up the levee whooping,” wrote the Missouri Republican of the Black strikers; the “insidious influence of the International” had delivered the city into the hands of “notorious Negroes.” In an interview given shortly after the strike, one of the leaders of the German section of the Workingmen’s Party told a sympathetic reporter that the strike organizers were surprised by the role that Blacks had played in the strike and had tried “to dissuade any white men from going out with the n—s.” That is to say, the whites-only leadership had lost control of the strike—and of the possibilities of interracial working-class solidarity being made plain in the streets.27

To regain control, the leadership ordered the suspension of mass outdoor meetings—and thus surrendered control of the streets to the police. As the strike leadership met behind closed doors on the morning of July 27, a crowd of workers—white and Black—gathered outside, demanding that the committee distribute arms to the strikers, including “a company of colored men.” Eventually, a group of workers broke into the room where the leaders were meeting but were turned away by the strike leaders, who said they had no weapons to provide to the crowd and admitted that they intended to surrender if the police stormed the building. That afternoon, the St. Louis Police, supported by a deputized citizens’ militia and armed with shotguns contributed by the St. Louis Gun Club and rifles from the federal arsenal in Rock Island, Illinois, arrested the leaders of the General Strike without a shot being fired. Two days later, US Army troops secured control of the rail yard in East St. Louis. Directing the deployment of federal forces in support of capital from Washington was the US secretary of the interior, Carl Schurz.28

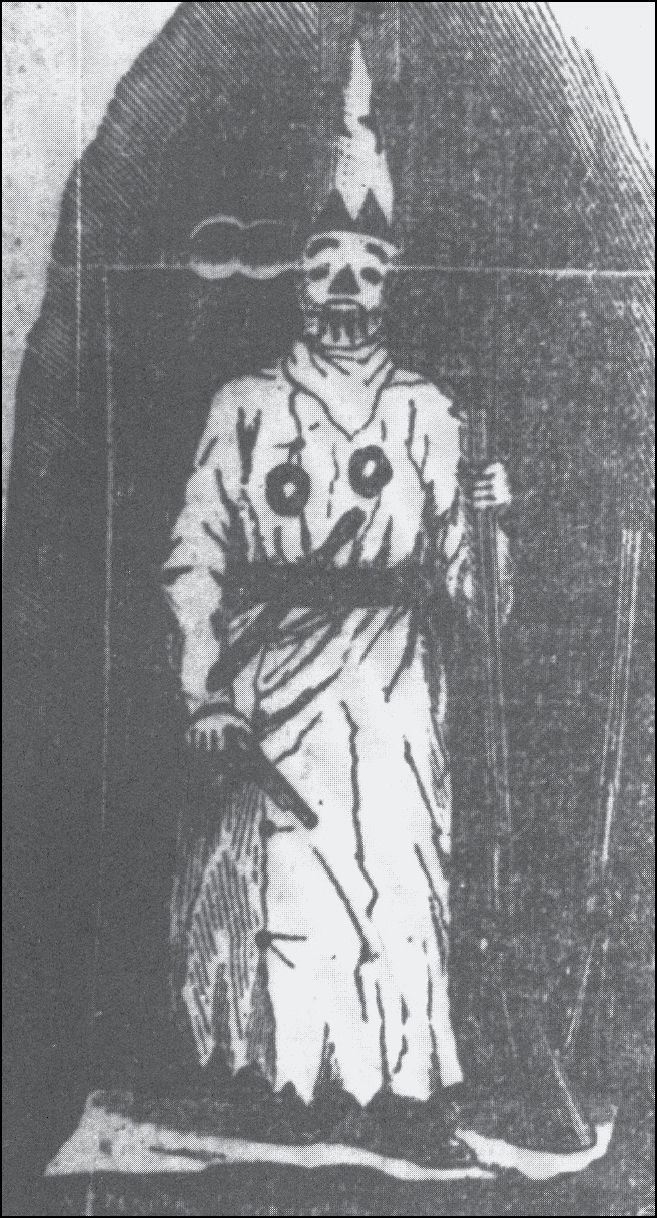

The Civil War in St. Louis ended with the overthrow of the Commune. The city’s leading men celebrated with a midnight parade the following year. Clad in a white hood and robes, the “Veiled Prophet” first patrolled the streets of St. Louis on the night of October 5, 1878, a revolver in one hand, a rifle in the other, a bowie knife looped through his belt. The parade was organized in a series of invitation-only meetings by elite St. Louisans in the aftermath of the General Strike. The Veiled Prophet that inaugural year, and the only one whose name has been officially acknowledged in the ongoing 140-odd-year history of the parade, was the city police commissioner, John G. Priest, who had continued to drill his deputized reserves—the reserve army of capital, as many as five hundred men—in the streets and parks of the city. Next to Priest on the Veiled Prophet’s float, reported the Missouri Republican, stood a “villainous looking executioner and a blood curdling butcher’s block.”29

An 1870s image of the Veiled Prophet from the Veiled Prophet parade, which was inaugurated in 1878 by city leaders anxious to reassert control over the streets of the city in the aftermath of the 1877 General Strike. The parade continues to the present day. (Missouri Republican, October 6, 1878, Missouri Historical Society)

It is as an aspect of the eventual success of the counterrevolution of property, rather than as simply “the politics of Reconstruction,” that we should understand one of the most notorious episodes in the municipal history of St. Louis—the so-called Great Divorce of 1876. In 1869, to punish and discipline “radical” Republicans in St. Louis (those who were supportive of the public education of Blacks and insufficiently eager to reenfranchise former Confederates), the state government of Missouri had transferred the power to assess, tax, and audit property within the city to County Court, a body that had until very recently boasted Joseph Weydemeyer as its auditor. By 1870, a secessionist movement had emerged within the city, with large taxpayers and business owners at its center decrying the high cost of “double government” and the effective subsidy provided by wealthy city dwellers to their rural neighbors in the county. In 1875, a freeholders board composed mostly of candidates endorsed by the Merchants Exchange and the Taxpayers League (to wit: property) was chosen in a special election and set about separating the city from the county (“home rule”) and designing new systems of government for each. The boundary of the city was stretched west to encompass the western edge of Forest Park. It is this line, an artifact of the Reconstruction-ending reconciliation of Liberal Republicans and propertied Democrats in their shared support of economic development and antipathy for taxes, that defined the hard boundary between city and county that hobbles the city’s development to this day.30

In the West, the counterrevolution of property took the shape of empire and Indian killing. Abraham Lincoln emerged from the Civil War as the “Great Emancipator,” but his political roots had more to do with the Black Hawk War than they did with the Black freedom struggle, and his political base lay in the free-soil wing of the Republican Party: antislavery, white supremacist, imperialist, and removalist. In St. Louis, the politics of the Republican Party was complicated by the leading role played by German liberals (like Boernstein), and even by German radicals (like Sigel and Weydemeyer). And yet, at the heart of all of these factions of the Republican Party were presumptions of empire: the idea that land in the West was there to be used as the standing reserve of white freedom, settler, liberal, or radical. All of the elements of the party of Lincoln in the West were imperialist, and all grounded their politics and their hopes on Indian land.

During the war, the president balanced his steps toward emancipation with a set of massive effective handouts to the free-soil wing of his party—that is, to whiteness and empire. Up to and even after the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln remained a committed colonizationist. In his annual message to Congress in December 1862—a month before the Emancipation Proclamation—the president assured the nation (or at least the West): “I cannot make it better known than it already is, that I strongly favor colonization,” arguing that “by colonizing the Black laborer out of the country… by precisely so much you increase the demand for and wages of white labor.” Through the later years of the war, Lincoln sought land in Panama and the Caribbean for Black resettlement, and, as late as April 1865, days before he died, he wrote of Black Union Army veterans: “I believe it would be better to export them all to some fertile country with a good climate, which they could have to themselves.”31

As much as he remained committed to ethnic cleansing, Lincoln remained a supporter of empire—the other aspect of the Benton-Blair tendency in the politics of westering white supremacy. In July 1862, as Congress passed a renewed Confiscation Act, which allowed for emancipation of enslaved people whose owners had been convicted of treason, the president signed the Morrill Act, which provided large land grants to the states that had remained in the Union in order to support the foundation of institutions of higher learning. Lest the meaning of “land grant” be misunderstood, it should be emphasized that these were grants of large sections of land (over seventeen million acres all told) that were to be sold to raise money to pay for the fabrication of entire institutions of higher education—facilities, faculties, future endowments—rather than the bare perimeters of land on which the buildings were later built. Indeed, some of the grants were quite distant from the campuses they eventually subsidized—the founding of Cornell University in New York State, to give only a single example, was partially funded by the sale of timberland in Wisconsin. The Pacific Railroad Act was signed into law the same month. It provided railroad rights-of-way and large adjacent grants of land to corporations seeking to build railways in the West. But the bulk of the subsidy came in the form of land that was far from any railway, almost 200 million acres of far-flung land that could be sold to finance the building of the railroad along the narrow path of its right-of-way. The Homestead Act, signed into law in May 1863, two months after the Emancipation Proclamation, provided white settlers free access to 160-acre tracts if they settled west of the Mississippi; as many as 1.5 million of them did in the years after the war, spread across 300 million acres of the West, or about a half-million square miles. Although it is conventional to understand the Civil War as a civil war—as a domestic conflict between the North and the South—from the vantage point of St. Louis (and, indeed, Washington), the war also had much to do with empire and the West.32

Taken together, the expropriating, land-distributing laws of 1862 and 1863 were the bill of rights for settler whites and corporate colonists in the nation’s postwar western empire—a neo-Bentonite program of western imperial development. They aligned the United States with pro-property liberals and settler whites in the West over and against the communists’ critique of property. And they were guaranteed by the power of the US military. In August 1862, Dakotas in present-day Minnesota rose against white homesteaders, killing as many as eight hundred in a thirty-seven-day war. Two thousand Indians were eventually rounded up and imprisoned at Fort Snelling (where Dred and Harriet Scott had met thirty years before), and 392 were tried for murder by the soldiers who had just defeated them in the field. In the mass trial, 323 were convicted and 303 sentenced to death. On the day after Christmas in 1862, a week before he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln ordered the simultaneous execution by hanging of thirty-eight Dakota men, in an exemplary act of retribution that remains the largest mass execution in the history of the United States (as well as a marked contrast from the emergent laws of war that governed the treatment of Confederate prisoners of war).33

Through the remaining year of the Civil War and the first years of Reconstruction—the years in which the United States defeated the Confederacy and ratified the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments—the US Army pursued a slow-rolling genocidal campaign on the plains. Emancipation in the East was shadowed at every step by imperialism in the West, as if the laws of the settler republic, or at least the racial prerogatives of the “white man’s country,” required that every step toward Black freedom be compensated with a step toward Indian annihilation. Then, in September 1863, US Army soldiers under the command of General Henry Sibley attacked a Dakota and Lakota summer camp, killing more than four hundred, mostly women and children. According to the Standing Rock historian LaDonna Bravebull Allard, in the chaos of the initial attack women in the camp tied their babies to the backs of their dogs and drove them out of the camp in a desperate effort to save them. As the dogs drifted back into the smoldering camp, the soldiers killed the babies one by one. In November 1864, Colorado volunteers under the command of US Army Colonel John Chivington massacred more than two hundred Cheyennes and Arapahos at Sand Creek, in the Colorado Territory; they celebrated their victory in a grisly festival of desecration and sexual mutilation of the dead.34

In 1868, to make way for the railroad, the army sent a treaty delegation to sue for peace with the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Dakota. The US commissioners included William Tecumseh Sherman, who would shortly succeed Ulysses S. Grant as the commanding general of the US Army, and the “Woman Killer,” William Harney. The resulting Treaty of Fort Laramie prescribed the boundaries of the Great Sioux Nation over almost 70 million acres of present-day South Dakota and Wyoming, including 32 million acres of “permanent reservation,” and it committed the Sioux, in return, to allow for the construction of the transcontinental railroad. The treaty, which required the approval of “three-quarters of adult male Indians” for amendment, remains the legal ground of Sioux claims against the United States: its terms have never been amended by the seven nations of the Sioux, although they have been sequestered in ever smaller portions of their domain in the 150 years since its signing.35

The US Army and the railroad men worked together to build the western empire. The railroad made it easier for the army to move soldiers and supplies from place to place, and the army provided security for railroad crews as they built their way across the Indian nations of the West. In 1867, Grant, as commanding general of the army, had declared that the completion of a transcontinental railroad would “go far toward a permanent settlement of our Indian difficulties.” To that end, an 1871 federal law unilaterally declared that the United States would make no further Indian treaties; over the following years, the army herded those Indians it could onto reservations and pursued the rest across the plains. Sherman, Grant’s successor, moved the headquarters of the army to St. Louis in 1874, hoping that he could more vigorously (read: murderously) prosecute the Indian wars away from his erstwhile civilian overseers in Washington. “We are not going to let a few thieving, ragged Indians stop the progress [of the railroads],” he declared in a letter to Grant. Under Sherman, the railroadization and racialization of the West went hand in hand. Indians found outside the boundaries of their reservations were to be “regarded as hostile and treated accordingly.” As Sherman wrote in 1873, “we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women, and children.” The term “settler colonialism” seems scarcely adequate to describe the close coordination of the railroad and the army—of investment and imperialism—in the West.36

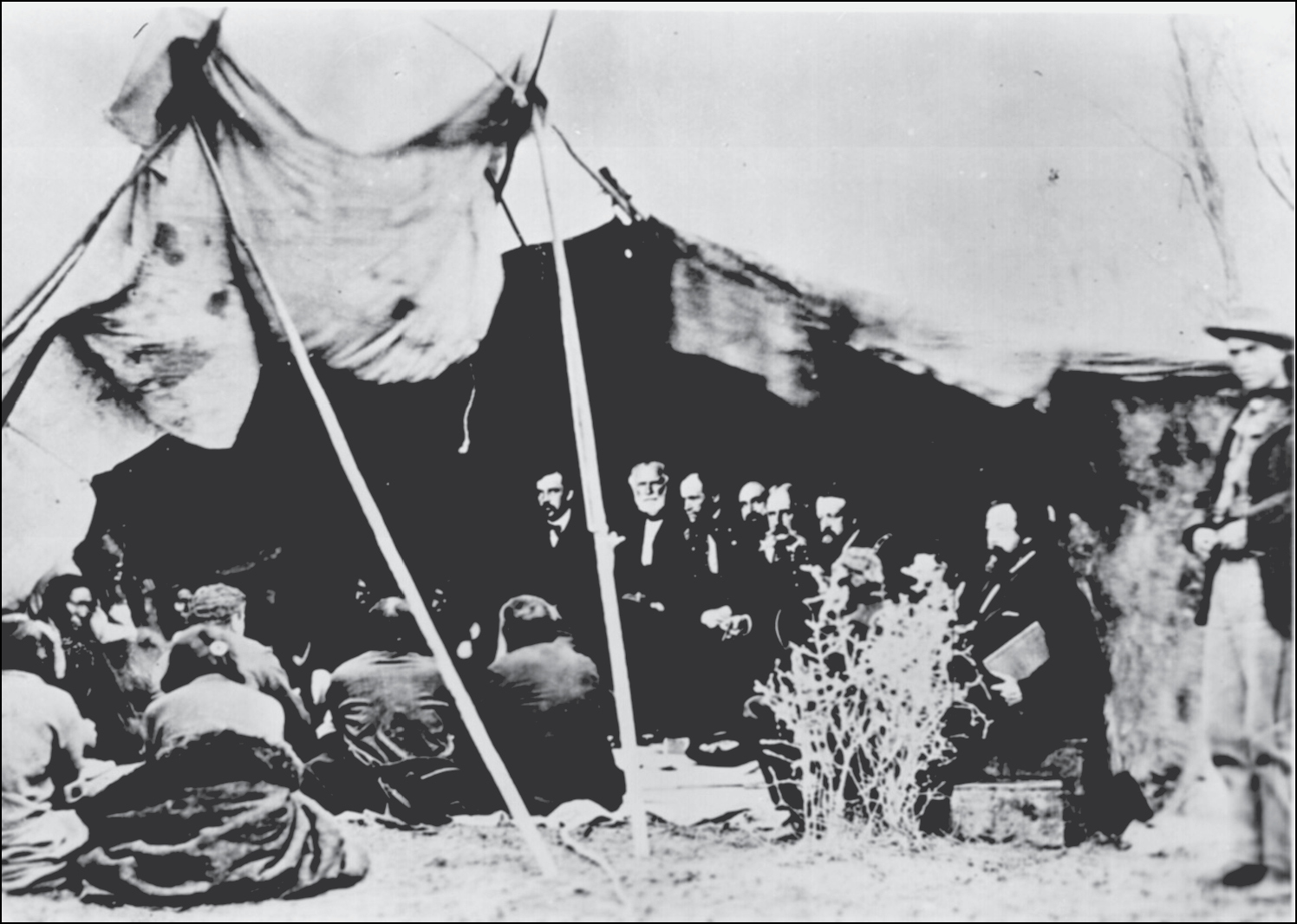

Along with General William Tecumseh Sherman, who moved the War Department to St. Louis in the 1870s, General William Harney represented the United States at the signing of the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868. Harney, who murdered an enslaved woman in St. Louis in 1834, was known among the Sioux as “Woman Killer.” He is second from the left among the white men seated in chairs, Sherman is third. (National Archives and Records Administration)

Many of the US Army troops pulled out of the South at the end of Reconstruction were immediately redeployed to an arc of forts moving westward like a shock wave from St. Louis. Though US Army operations and bases moved farther west in the years after the Civil War, the city remained the site of the War Department, under General Sherman, and it continued to be the headquarters of the army’s Department of the West as well as its Quartermaster Corps. Jefferson Barracks would be the intake and training base for all US Army cavalry units for the duration of the nineteenth century. Confederate as well as Union Army veterans served at Jefferson Barracks and in the western army of the 1870s, just as Confederate as well as Union Army veterans worked on the railroad and provided security along its leading edge. In these years, the reunification of the United States was accomplished not through the pacification of southern whites and the revolutionary elimination of white supremacy, but in continental conquest in the service of capitalist expansion. The counterrevolution of property and what the historian David Blight has termed the “romance of re-union” followed the parallel tracks along the lines of the Union Pacific, Central Pacific, and Southern Pacific Railroads.37

As well as former Confederates, Black soldiers fought Indians in the West. The famous Black soldiers of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries, colloquially known as the “Buffalo Soldiers,” were inducted into the army and trained at Jefferson Barracks. Even with the tactical advantages afforded by the railroad, the US Army would have been unable to wage war on the plains without horses, and the Ninth and Tenth made up about 10 percent of the army’s mounted units, a percentage comparable to that of Blacks in the infantry. Often romanticized by historians, Black soldiers in the West slept in segregated quarters (as they had in training at Jefferson Barracks) and were provided with separate chaplains so that the segregation could be maintained through the Sabbath. Their own white officers and white soldiers in other units abused them and taunted them, and there were occasional fights between Black and white soldiers, for which the Black soldiers were almost uniformly held responsible. Their story is often told as an emblematically American fable: men so devoted to freedom that they were willing to suffer injustice in order to exemplify a better pathway to their white antagonists. And perhaps that is true. But so is this: the pathway to freedom in the late nineteenth-century United States was through Indian killing. It is, as the historian Quintard Taylor has written, “a painful paradox” that Black soldiers in the West risked their lives in defense of the imperial promise of the “white man’s country.” The legend of the “Buffalo Soldiers” became an alibi for empire, cloaking annihilationist wars in the trappings of freedom.38

It was Carl Schurz, the German radical turned Missouri liberal and Bentonite imperialist, who outlined the most coherent alternative to Indian-killing-as-the-course-of-imperial-progress in the 1870s and 1880s. As head of the US Interior Department, Schurz had nominal jurisdiction over Indian affairs, and beginning in 1877 he sought to transform that administrative responsibility into actual control. Schurz’s main antagonists in the effort were Generals Sherman and Philip Sheridan, who tried in 1878 to have Indian affairs moved out of the Interior Department and into the War Department. In contrast to Sheridan’s notorious statement that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian,” Schurz advocated a policy that was later summarized by William Henry Pratt, a onetime lieutenant in the Tenth Cavalry and founder of the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, as “kill the Indian, save the man”—pacification through the separation of Indian children from their families and their reeducation in eastern boarding schools. In other words, cultural genocide. Upon the founding of Carlisle in 1879, Pratt stated that the Indian school model had no greater advocate than Schurz.39

Within a few years, three-quarters of Native children were being taught in boarding schools run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (within the Interior Department), one-third of these in off-reservation schools like Carlisle. For Pratt and Schurz, education and privatization of tribal lands were pathways by which Indians might move from being the “occupants of the soil” to actually being able to have land “they could call their own.” In Schurz’s vision, citizenship and private property were mutually defining: only by learning how to cultivate the land as owners could Indians become citizens; only by learning to be citizens could they become worthy of the land upon which they had always lived, but never truly possessed according to Schurz.40

It was under Schurz that the push for the privatization of Indian lands culminated in the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887. The Dawes Act dissolved the common holding of American Indians and pulverized their nations into 160-acre plots, assigned one at a time and on the basis of individually held parcels of private property to every Indian head of household. Because the reservation lands and other common lands, as restricted as they were, had once included land for hunting and seasonal migration, there was a great deal of unassigned land left over after severalty—as much as three-quarters of what had been Indian territory in the years leading up to 1887. The Dawes Act deemed this unassigned Indian land “surplus” and provided for its distribution to white homesteaders, who once again began to embark from St. Louis by the tens of thousands.41

For a moment following the Civil War, it seemed as if St. Louis, the city of both Sherman and Schurz, would become the first city of the American empire, advancing “steadily and surely to her predestined station of first inland city on the globe,” in the words of the journalist Horace Greeley. Boosters in the city led a brief campaign to have the nation’s capital moved west to the banks of the Mississippi, going so far as to propose the brick-by-brick dismantling of the Capitol and the White House and their reassembly on the grounds of Jefferson Barracks. The idea’s principal local booster was newspaperman Logan Uriah Reavis, who argued that “the ruling power of a country should be located in the midst of its material power.” Walt Whitman and William Tecumseh Sherman supported the plan, as did DeBow’s Review, the principal journal of the commercial South, and an 1869 convention held at the Merchants Exchange in St. Louis at which the governors of twenty-one states expressed their support for the proposal.42

In the end, the Capitol remained intact and in Washington, but the fact that the proposal was taken seriously provides a reminder of the status of St. Louis, the West, and the empire in the minds of white Americans in the years after the Civil War. As one of those who lingered on the idea long enough to take it seriously reasoned, “St. Louis is the center of the Mississippi Valley—that this Valley is the center of the United States—and the United States the center of the whole world.” According to the logic of the imperial reason, there was a case to be made for St. Louis, one that was only bolstered in the eyes of the western visionaries by the fact that the 1870 census revealed that the city had passed Baltimore, Boston, New Orleans, and Cincinnati to become the fourth-largest in the United States—behind only New York, Brooklyn (which did not merge into New York City until 1898), and Philadelphia and, most importantly, still ahead of Chicago.43

But if the Mississippi River was the historic reason for the city’s imperial rise, it was also the limit. On May 10, 1869, standing on the traditional lands of the Western Shoshone at what is now called Promontory, Utah, Leland Stanford had driven a golden spike into the ground, securing the link between the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads, and between the East, the Midwest, and the Pacific. At the other end of the line, however, was not Benton’s St. Louis but the mushroom metropolis on the banks of Lake Michigan—Chicago, which, by way of Rock Island, had a bridge. Indeed, by 1868 there were three bridges across the Mississippi that connected the East to the West via Chicago. St. Louis had none.44

There were both simple and complex reasons for the difference. The simple reason was that Missouri was across the river from Illinois. Any bridge that crossed the Mississippi at St. Louis would have to be built in coordination with a state government that had little to gain by promoting competition with the city of Chicago. The complicated reason had to do with the fact that the American empire in the West was not simply built out of iron, steel, and lead, blood, sweat, and tears; it was also built out of paper. It was an empire of capital as well as arms. And it turned out that there was almost as much money to be made in not building railroads as there was in building them.

The efforts to build or block the bridge pitted St. Louis railroad interests in combination with downstate Illinois commercial interests, who wanted a bridge across the Mississippi at St. Louis, against Chicago railroad interests and St. Louis ferry interests who did not. In the years before the war, Chicago-based investors had managed to acquire the sole rights to build a bridge across the river in St. Louis, which they held, doing nothing, as they unfolded link after link of railway lines connecting the Windy City to the West.

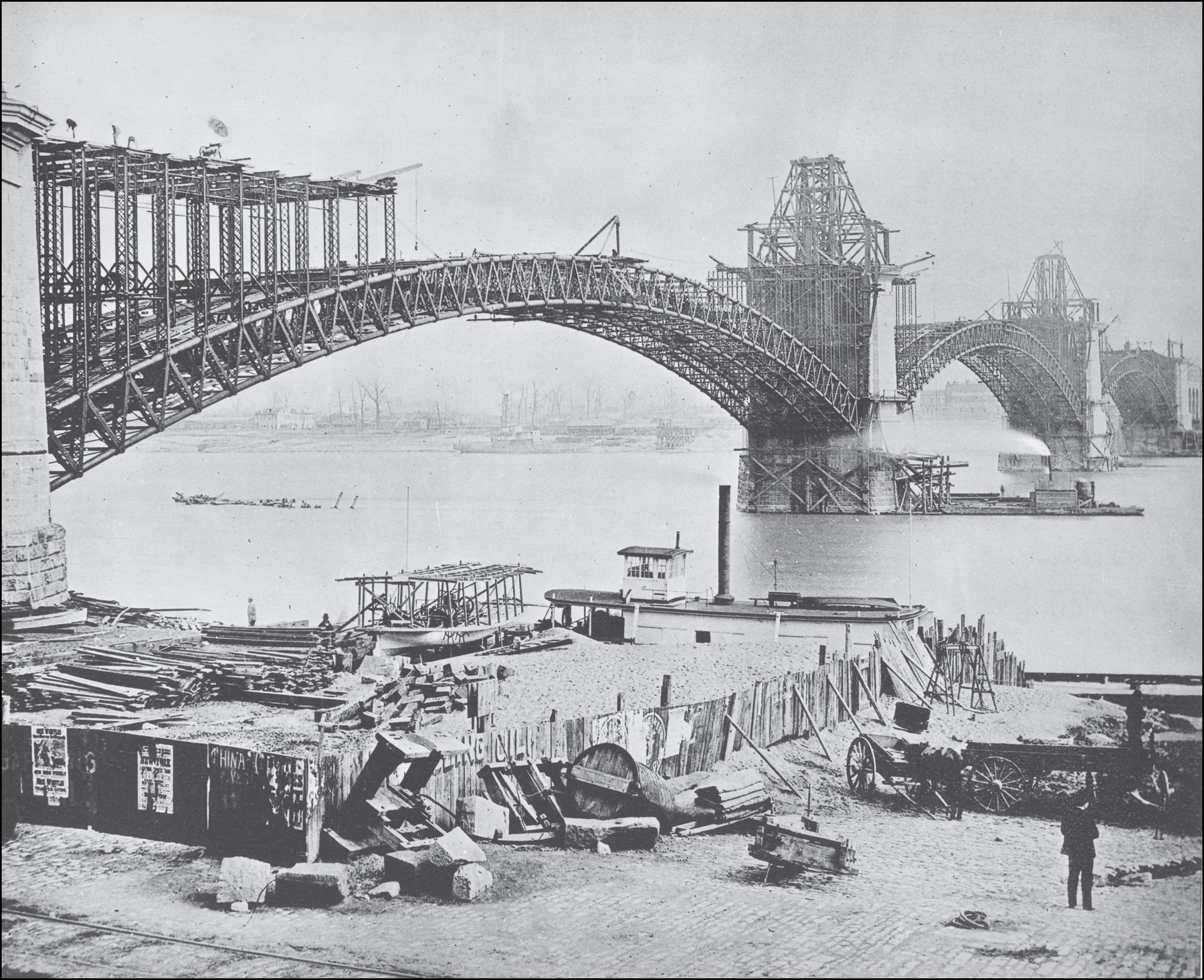

Excavation for the bridge piers finally began at the foot of Washington Avenue in November 1869. The principal investor in the project was the New York magnate and banker J. P. Morgan, and the principal engineer for the project was the visionary James B. Eads, who had started out as a salvage man working (literally) on the bottom of the Mississippi River. For the bridge across the Mississippi, Eads used a method never before employed in the United States—pumping compressed air into underwater caissons, effectively creating a giant submarine, inside of which the piers of the bridge could be built up toward the surface. The method was ingenious but, in an era before the connection between rapid decompression and the formation of nitrogen bubbles in the bloodstream was widely understood, deadly: of the nearly 600 men who worked in the caissons, 119 became severely ill and 14 died, each death evidence of the bridge builders’ daily decision that construction must continue no matter the human cost. The bridge, which, at its opening, boasted the longest rigid span in the world (its 520-foot central arch), was completed in July 1874 and named for James Eads.45

By the 1890s, twenty-two railways had converged at St. Louis, more than at any other point in the United States (although rail traffic through Chicago was greater), and the city had completed the massive, Romanesque Union Station, billed as “the largest, grandest, and most completely equipped railroad station in the world,” in 1894. But the railroads were impressive not only as material objects but as opportunities for the wealthy and the canny to extract wealth from empire. In 1878, the Washington Avenue Bridge Company was forcibly dissolved by J. P. Morgan, acting on behalf of those who held the first and second mortgages on the bonds that had been sold to finance the bridge’s construction. Acting through a partner, Morgan promptly repurchased the company at auction and thus ended up with the bridge while bilking the lesser-status bondholders out of their share. By the 1890s, the financier Jay Gould controlled enough of the traffic across the bridge that he could also control economic development in the city of St. Louis by setting the rate for transporting a ton of coal across the river. At the going rate of twenty cents per ton, it was worthwhile for industrialists to build their steel mills and packing plants in East St. Louis, which experienced terrific growth under the dominion of what those on the west side of the river came to call “the bridge arbitrary.” While the railroads brought business to St. Louis, they also shaped the city’s economic geography in their own image and their own interest.46

Still, there was plenty of money to be made in the imperium of St. Louis. In 1870, the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad (the MKT, or the Katy), having reached the border of Indian Territory in Oklahoma, acquired the right to land grants to build through to Texas and Mexico. In the following decades, both the city’s railway network and its financial interests unfolded toward the Southwest and Latin America—the quarter-section of the continent between the city’s long-standing trade routes along the Santa Fe Trail and up and down the Mississippi and out into the Gulf. Tracing out the pathway of the MKT on the map in 1873, the Missouri Republican enthused that “all of Mexico would become part of the commercial empire of St. Louis,” momentarily diverting Benton’s dream of a pathway to the Pacific toward the commercial (and military) conquest of the Southwest. It was the MKT line and land grants, among other factors, that provoked the Red River War of 1874 and the final military defeat and forced sequestration of the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho.47

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, St. Louis again became a hub for the processing and resale of resources extracted from the West. On the Southern Plains, as cattle replaced bison—which were overhunted in the early 1870s and wantonly slaughtered by soldiers in the later years of the decade—the packing plants in East St. Louis came to occupy a position second only to those in Chicago in the burgeoning “Republic of Red Meat.” In these years, the city of St. Louis itself became the third-largest miller in the nation—shipping flour to Mexico and on to Central and South America via its southwestern rail link—and the third-largest market for pressed cotton in the United States. As well as agricultural processing, trans-shipment, and export, the city developed a large manufacturing sector in the years after the Civil War, second only to Chicago’s in the West in terms of capital investment. Flour mills and cotton presses, breweries and cigar factories, shoe and shirt manufacturers; rolling mills, iron foundries, and eventually steel mills; streetcar, carriage, and railcar factories; stoveworks and sofas—all manner of goods were made in St. Louis and destined for sale in the emerging markets of Texas and the Southwest, the Pacific, and especially, Latin America.48

In 1875, the St. Louis pharmaceutical exporter John Cahill founded a new commercial magazine focused on the export trade that he believed would save the city from “commercial stagnation.” Called El Comercio del Valle, it was printed largely in Spanish, with some English, and featured an engraving of the Eads Bridge on the masthead. By the 1880s, El Comercio del Valle had twenty-four thousand subscribers in the city, throughout the Midwest, and in Latin America—Mexico, Costa Rica, Honduras, Nicaragua, Cuba, Brazil, Chile, and Venezuela. The magazine soon came to serve as a sort of official organ of the Mexican & Spanish-American Commercial Exchange, which was housed in a large three-story building in the heart of the city’s downtown, on the corner of Eighth and Olive Streets. Though the articles in El Comercio del Valle were generally printed in Spanish and English, the advertisements were only in Spanish, and they provided a view of the city’s manufacturing and export sector comprehensive enough that it could have served as a ready alternative to the city directory: the William Lemp and Anheuser-Busch breweries; Shapleigh and Simmons Hardware; Meyer Brothers Drugs and Mallinckrodt Chemical; the St. Louis Car Company and the MKT; the Hamilton-Brown Shoe Company; Shapleigh rifles and revolvers, and ammunition from the Western Cartridge Company; and on and on.49

The election of Porfirio Díaz as president of the Republic of Mexico in 1877 provided the capitalists of the Mexican & Spanish-American Commercial Exchange with a terrific opportunity. Díaz almost immediately appointed Cahill, a US citizen, as Mexican consul in St. Louis, a position from which Cahill and El Comercio del Valle could assist in Díaz’s effort to draw foreign capital to Mexico by putting the country’s assets up for sale. In these years, the MKT linked directly into the trunk line of the Mexican National Railway.50

Over the last twenty years of the nineteenth century and into the first decade of the twentieth, St. Louis capitalists bought mines, railroads, factories, and farms all over Mexico. In 1883, Díaz visited the city and gave a speech in which he promised that the city of St. Louis had a “deep and permanent interest” in the future of Mexico. By that time, the St. Louis oilman Henry Clay Pierce had become the chairman of the Mexican Central Railway, the Mexican Pacific Railway, the Mexican-American Steamship Company, the Mexican National Construction Company, the Mexican Fuel Company, the Tampico Harbor Company, and the Mexican Bank of Commerce and Industry. He had built and owned oil refineries in Mexico City, Monterrey, Vera Cruz, and Tampico, and since 1886 he had held an exclusive license to sell Mexican Fuel Company petroleum in Mexico. So great were St. Louis’s interests in Mexico that the revolution that finally overthrew Díaz in 1911 was portrayed in some quarters as a simple proxy struggle between St. Louis capitalists and interests based in Great Britain: “A fight which will have on one side the interested of the oil department of Weetman Pearson of Great Britain, and on the other side the Waters-Pierce Oil Company of St. Louis is promised Mexico in the near future,” predicted the Mexican Herald in January 1908.51

The merchants and manufacturers of St. Louis had been enthusiastic supporters of the 1898 Spanish-American War, which they viewed as an opportunity to expand both their commercial reach and their way out of the depression that had begun in 1893. St. Louis had long-standing connections to Cuba, having served as a refinery for Cuban sugar brought up the Mississippi River since the 1840s, and the city had shipped flour, shoes, and machinery for sugar mills to the island since the 1880s. In the years after the war, St. Louis had become the second-largest producer of shoes in the nation (behind Boston), and the St. Louis–based Shoe and Leather Gazette editorialized strongly in support of Cuban independence through much of the 1890s. But it was not just Cuba that these inland imperialists imagined as a part of the commercial dominion of St. Louis: “The Stars and Stripes should henceforth float forever from the Philippines,” declared an editorial in the St. Louis Star in 1898. Benton’s dream of Pacific empire found second life in the counter-revolution of property.52

The merchants and manufacturers of St. Louis and East St. Louis made good money off the Spanish-American War (as they did from Great Britain’s Boer War between 1899 and 1902 in South Africa). Horses, mules, saddles, and shoes were hallmark products of the city of St. Louis, and in the last years of the nineteenth century they were shipped all over the world in the service of empire. Business only improved in the wake of the 1898 war. The St. Louis Car Company was soon shipping streetcars, freight cars, and locomotives to Manila, Honolulu, San Juan, Havana, Mexico City, Santiago, Buenos Aires, Lisbon, Rio de Janeiro, London, Berlin, Bordeaux, Cape Town, and Odessa. Shoes from St. Louis were shipped all over the world in the years following the war, $2 million worth in 1906 alone. “American shoes are certainly following the flag,” enthused the Shoe and Leather Gazette, emphasizing the connection between war, empire, and the sale of shoes. In these years, St. Louis companies like Mallinckrodt Chemical and Anheuser-Busch became global brands, building on existing connections throughout the Americas but also expanding to Asia and even Australia; Anheuser-Busch reported a 50 percent rise in its global sales over one year in 1899. It was perhaps no coincidence that Thomas Hart Benton’s vision of the commercial imperium of the city of St. Louis found its fullest historical expression partly under the military leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, who would publish a fawning biography of Benton in the year following the war.53

Of the neo-Bentonites, only Carl Schurz expressed any doubts about the conquest of Cuba and the Philippines (as well as Hawai‘i in 1893), but his worries were strictly racial in character. Hearkening back to the imperial white supremacy of the free-soil movement, Schurz simply did not think that the United States should risk bringing any more dark-skinned people—“tropical peoples and more or less barbarous Asiatics”—under the jurisdiction of the United States, no matter how far-flung their precincts. Schurz supported war in Cuba and the Philippines, but only to provide their markets access to American goods, not to provide their people access to American citizenship (or even quasi-citizenship). Although he would probably have favored the term “Anglo-Saxon racial purity,” Schurz was outlining the premises of what would later be known as “the imperialism of free trade”: the process by which the US government and American corporations sought to exert indirect rule across the globe in the interest of capital.54

According to the standard measures, these were good years for the city of St. Louis. The population, which had been 350,000 in 1880, rose to 450,000 in 1890, then to almost 600,000 in 1900. Beginning in the 1870s, the capitalists of the counterrevolution were building mansions on Vandeventer Place, an almost mile-long gated street that had its own private security force and whose residents included Henry Clay Pierce and Edward Mallinckrodt. In the 1880s, they began to move to Compton Hill, just east of Grand Avenue, where the Busch family had a mansion, and then to Westmoreland and Portland Place in the Central West End, where there were other members of the Busch family, as well as railroad magnates, bank directors, import-export merchants, and large manufacturers. By 1900, the city’s power brokers had come to be known collectively as “the Big Cinch.” These heirs of the old families and sons of the new ones lived within a few blocks of one another and the corner of Lindell and Kingshighway (and Vandeventer Place), and their names—Carr, Glasgow, Maffit, O’Fallon, Lucas—still adorn the street signs and city limits that define space in the St. Louis metropolitan area. The de facto leader of the group was David Francis, the erstwhile bridge entrepreneur who would forever be remembered in St. Louis for presiding over the World’s Fair in 1904. They had retaken the city from the mob in 1877, and for the next three decades they did more or less what they wanted with it. Du Bois termed them and those like them across the country “the dictatorship of property.”55

On May 8, 1900, 3,325 streetcar workers seeking recognition of their union, the reinstatement of fired organizers, and a ten-hour workday went on strike in St. Louis. The strike was a direct challenge to the local rule of the city’s imperial merchants, manufacturers, and bankers, though not to the city’s racial order; by 1900, all of the streetcar workers were white, and thus their strike might be seen as a demand for inclusion in the spoils of white supremacy and empire as much as a genuine challenge to their accumulation. “Sons of ditch-diggers aspired to be spawn of bastard kings and thieving aristocrats rather than the rough-handed children of dirt and toil,” Du Bois wrote of the white working class in the era after the suppression of the General Strike.56

The St. Louis Streetcar Company, which had recently consolidated control over all the lines in the city, brought in strikebreakers from Cleveland in order to keep the trains running, and it successfully petitioned a federal judge to allow the formation of a property-protecting posse comitatus, drawn from among the self-declared “better elements in the city.” The workers and their families organized alternative public transportation on horse-drawn freight wagons, threw dead frogs and bricks at the windows of passing trains, and built fires on the tracks. There were even reports of dynamite being found concealed beneath cabbage leaves on the rails heading out to the comfortable suburbs of the Central West End.57

On June 10, a parade of striking streetcar workers marched across the Eads Bridge and up Washington Avenue on their way home from a picnic in East St. Louis, where they had joined with striking workers from that city. They were carrying flags and marching to the beat of a drum as they passed the downtown “barracks” that housed the “posse” the sheriff had raised to ride the streetcars during the strike. There was a shot, fired by whom no one ever really established, although the sheriff later said that one of his men had dropped his gun on the ground while chasing a striker who had thrown a brick. Then there were many more shots from pistols and riot guns as the posse shot down the marchers “like dogs,” in the words of the president of the Streetcar Workers’ Union.58

Three of the marchers died at the scene, and one other made it, fatally wounded, to City Hospital. Eight others were seriously wounded but survived. Although the posse later alleged that a series of unlikely coincidences had preserved the police from injury at the hands of marauding workers—workers aiming at policemen being jostled as they shot, the guns of workers in the act of shooting policemen jamming, a gun barrel protruding from a knothole in a fence behind which an old man who had nothing to do with the strike was shot dead by the police mysteriously disappearing—and although the police later exhibited cards embossed with the words “Union or Nothing. Liberty or Death,” which they said many of the marchers had been carrying hidden in their hats, there was no evidence that any of the marchers had been armed, or that they had intended to fight with the police or the posse.59

Twenty of the striking marchers were arrested and held for trial in the aftermath of the violence, and the following day the city’s mayor issued a proclamation barring the city’s citizens from “gathering in numbers on the streets or in public places” and declaring that “jeering or abusive language” would not be tolerated within the limits of the city of St. Louis—effectively outlawing the ongoing strike for the duration of the three-day order. The governor, having spoken to the mayor by telephone, made a statement that he was entirely satisfied that the posse had acted properly. Meanwhile, twenty-three of the city’s lawyers formed a new posse, arming themselves and patrolling the streets to make sure that armed men stayed off the streets, as the mayor had ordered. Indeed, the sheriff announced, application to join the posse had skyrocketed after the massacre, and he soon expected to have as many as 2,500 deputies patrolling the streets and riding the streetcars along their reopened routes. The following day, sixty Civil War veterans were deputized and, dressed in the outfits worn by Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders,” turned out for duty. Before long, workers began to be brought before the Police Court and charged with the offense of “jeering” at passing train cars and policemen. The habits of imperial rule died hard.60