6 | THE BABYLON OF THE NEW WORLD

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.

We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.

For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song; and they that wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion.

How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?

—Psalm 137:1–4

THE 1904 WORLD’S FAIR IN ST. LOUIS IS REMEMBERED BY SOME as the high-water mark of the city’s history—the moment when all the world was assembled in tribute to the city’s greatness, the moment at the crest of the rise, before the beginning of the long decline. But for the railroad barons and industrial princes of the Big Cinch, the fair was intended to mark not an end, but a beginning—the self-conscious passage from one period of imperial history into another. Termed the Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exposition, the 1904 World’s Fair celebrated the “civilization” of the continent. And on that legacy of conquest, it founded a vision for the coming century—modern, technological, commercial, imperial, American. “The Babylon of the New World,” the civic booster and impresario of the move-the-capital-to-Missouri movement Logan Uriah Reavis termed St. Louis at the turn of the century. Reavis meant it as a compliment, emphasizing the idea of an imperial capital to which all of the known world paid tribute, a center of learning and culture. And indeed, in its ambition, scope, and arrogance, the fair was a Babylonian gathering-in of all the peoples, things, and knowledge of the known world, a vast imperial harvest. But the comparison was double-edged, at least for anyone who had read the Old Testament. For St. Louis at the turn of the century was more like the Babylon remembered by the Israelites: presenting itself to the world in the splendor of its boundless ambition, but rotten at the core.1

If St. Louis was Babylon, the city where the assembled wonders of civilization could never quite conceal the imperial corruption, then Theodore Dreiser was its chronicler—or at least its gossip columnist. The journalist and novelist, author of Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy, began his career as a newspaperman in St. Louis, and the city figured prominently in his autobiography, Newspaper Days. Dreiser is often credited as one of the progenitors of American naturalism, the effort to set aside conventional morality in favor of the unstinting representation of the base motivations and animal urges that explain human behavior and the Darwinian underpinnings of modern social existence. St. Louis was Dreiser’s laboratory for the exploration of human urges and desires, his test kitchen. He devoured St. Louis, moving freely between the enclaves of imperial whiteness and the leftover spaces inhabited by the driven-out and the left-behind, those fighting for survival on the underside of the history of American freedom. His chronicle of Gilded Age St. Louis provides an itinerary of the pleasures of impunity and empire, of the places a man like Dreiser could go and the things he could do—the things that money would buy and whiteness would allow—as well as a sense of the disquiet and moral decay at the heart of the city that W. C. Handy called “the Capital of the Sporting World.” St. Louis was the players’ playground, a place where the right kind of man with the right kind of money could get anything he wanted.2

Dreiser, writing for the Globe-Democrat and then the Republic, spent a lot of time in the taverns and alleys of the city’s downtown, where the poor built a vernacular metropolis interleaved with the busy streets of the rising city. These were people who had come to St. Louis in the years after the Civil War and the failure of Reconstruction, seeking safety and a better life and looking for work in the breweries and foundries and brickworks of the city: African Americans from the South, leaving behind the lynching, white-capping, and sharecropping of the period historians often refer to as “the Nadir” of Black life in the United States; Russian Jews fleeing pogroms; poor whites from rural Missouri. Between 1880 and 1890, the population of the city grew by almost 30 percent, to 450,000; by 1900, it was closer to 600,000. The rail networks and rivers that accounted for the city’s continued imperial rise also facilitated a second-order accumulation of racial, political, and economic refugees.

Dreiser was both attracted and repulsed by the raw, open lives of the city’s poor: by the chop suey houses that were “hangouts for crooks and thieves and disreputable tenderloin characters generally”; by “those horrible grisly waterfront saloons and lowest tenderloin dives and brothels”; by “the patois of thieves and pimps and lechers and drug fiends”; by the Jews and the Blacks and the “rundown Americans,” by which he meant poor whites, who lived in wooden shanties built up in the alleys where even the police were afraid to go alone; by “the ragpickers, chicken dealers, and feather sorters… the tang of the life here, rich, complicated, and mystic.”3

In the summer of 1893, in the first months of the depression that would later serve as the frame for Sister Carrie, Dreiser received a tip that took him to “an old half-decayed brick barn” in an alley behind North Levee Street. An old man had been caught paying a girl of eight or nine a couple of pennies and a piece of candy to give him what Dreiser winkingly referred to as a “French Massage.” The police had rescued the man from an angry mob and taken him to the station on North Seventh Street, but by the time Dreiser arrived the man had been released. Indeed, there was no record of his having been arrested at all. When Dreiser finally managed to wring the man’s name out of a police captain he knew, he was told that the man, named Nelson, had been let go without charges. “He’s an old man with a big wholesale business in 2nd Street, never arrested before, and he has a wife and grown sons and daughters,” the policeman explained. So great was what he had to lose that it could not be taken from him, not for the sake of a crime against a poor little refugee girl in any event. Not in St. Louis.

Dreiser took the streetcar out to the West End, where he found Nelson sitting on the steps of his large brick house. The wholesaler sprang up, hurried to meet Dreiser at the gate, and offered him a bribe to kill the story. In his own telling, Dreiser was neither surprised by what the man had done nor terribly upset by it. Dreiser “could not,” he wrote, “help sympathizing” with him. “Sex vagaries, as I was beginning to see were not as uncommon as the majority supposed… was not the child, with its instinct to accept almost as much to blame as the man?” He was only surprised that the man had offered him just $10 to kill a story he thought was probably worth a thousand. Not until he tried to submit the article he wrote on the streetcar going back downtown did he realize that the wealthy man was playing a deeper game than he had anticipated. “You can’t make much out of a case of that kind,” the editor at the Republic told Dreiser. “The public wouldn’t stand for it. You can’t tell what really happened. And if you attack the police for concealing it, then they’ll be down on us.” The crimes of men like Nelson were recorded in white ink.4

Dreiser’s trip out to the West End was not his only experience, or even his primary one, with the passageway between St. Louis as represented in the stately brick facades and St. Louis as lived in the back alleys and bordellos. Indeed, Dreiser was at that very moment on a journey of discovery, celebration, and full-scale philosophical elaboration of his own “idiosyncrasies.” Through his work at the paper, he had learned to see what others referred to as the “vice” district as something else, as what a later generation of scholars might call an “interzone” where white men went to seek forbidden pleasures—“a banker, who had an amazing studio in the red-light district”; “a clairvoyant” who lived near the banker; “a lawyer and a railroad man, both bon vivants in the local sense, and both having rooms away from their wives… and presumably a wider knowledge of the world than the rest of the city provided them.” Before long, Dreiser himself decided to join them and took a room on Morgan Avenue downtown.5

Like the vice sojourners whom he emulated, Dreiser was a sybarite—a seeker of sensations beyond the ordinary or allowed. Dreiser’s autobiography is 673 pages long, and perhaps fully one-third of those pages are devoted to a minute accounting of his sexual fantasies, frustrations, flirtations, and episodic fulfillment. Although these passages are wildly more interesting than his detailed accounts of the haberdashery and grooming habits of the various men he met in the newspaper business, they are so alarmingly specific as to be what young people today call “cringey.” Neither Dreiser’s self-abuse nor his self-satisfaction, both of which his autobiography documents in detail, require description. All that is relevant is his fear that youthful masturbation might have made him impotent and his constant anxiety that he had not pleased the women he slept with—an anxiety about women’s sexual self-possession that turns out to have been less a personal peculiarity of Dreiser’s than an index of a deeper societal reckoning.6

During the same years that Dreiser was living on Morgan Avenue, the novelist Kate Chopin was living and writing in another part of St. Louis, the city of her birth. Though Chopin’s fiction is largely set in Louisiana, where she lived during the 1870s, she had returned to St. Louis in 1882 and lived there until her death in 1904. Chopin’s most famous novel, The Awakening, written in St. Louis during these years and published in 1899, tells the story of Edna Pontellier, a society woman, wife, and mother who has an affair with the younger Robert Lebrun. It is the story of life lived along the shoreline of white female sexual longing and fulfillment, a world whose existence Dreiser could intuit, but only imagine through the parallax of his own anxiety. Dreiser’s anxiety—or at least the anxiety that white women might have unfulfilled sexual desires and that those desires might lead them into the arms of darker men like the suggestively named Lebrun—was perhaps shared by some of the leading men of St. Louis, who saw to it that The Awakening was removed from the shelves at the Mercantile Library and that Chopin would no longer be received in polite society.7

Closer to Dreiser’s beat at the newspaper, his new apartment, and his understanding of sexuality and desire is the autobiography of Nell Kimball, which provides a catalog of the tricks used by sex workers to please men like Dreiser; indeed, so luridly detailed is that catalog that some have speculated that it was written by a man. However one reads it, one thing is clear: at the center of paid sex was the performance of female pleasure. “We became very good actresses in faking through the sexual pleasure game to a full blown orgasm, thrashing about and crying out love talk and rolling our heads. Most of the time feeling nothing, and thinking all the while maybe the codfish cakes were too salty at lunch, or wondering if tassled high-buttoned shoes were proper for Sunday walking in the park?” That was supposed to be funny, but the insight at its core, about the alienation of spirit from the business of sex in the downtown brothels, was treated with more gravity elsewhere in Kimball’s memoir in the observation that the knives in the downstairs kitchen were locked up at night to make sure that the girls did not cut or kill themselves.8

The fact that one could pay for a performance provided men like Dreiser with a shortcut around the question of female desire—a contractually agreed fiction that was enough to get successfully to the end of the script. But the existence of that shortcut was also an insistent reminder of something that men could never really know. For Dreiser, the uncertainty—the epistemology of desire amid the social architecture of deception—left him wondering many years later whether he had been up to the job in long-ago sexual encounters. It could be said that the knowledge of female pleasure—that women might or might not enjoy sex—was something from which Theodore Dreiser never recovered.

Whether dogged by fears of sexual inadequacy or perhaps simply seeking something new, Dreiser moved to the apartment on Morgan Avenue late in the summer of 1893. His room overlooked a glass-roofed music hall, “whence nightly and frequently in the afternoons, especially on Sundays, issued all sort of garish music hall clatter… until far into the night.” He thought he was close to getting what he was seeking one night in his room when he kissed two women in turn. The three of them were fantasizing out loud about dressing the women as men and sneaking into the club downstairs—a place forbidden to white women. Just the proximity of that club electrified the atmosphere in Dreiser’s room up above.9

Not long after Dreiser moved to Morgan Avenue, a Black man named John Buckner was lynched in Valley Park, west of St. Louis. Buckner was accused of raping a white farmer’s daughter, and on January 16, 1894, he was kidnapped by a mob from police custody and hung from a railroad bridge over the Meramec River. Dreiser covered the lynching for the Republic and arrived in Valley Park in time to witness both the kidnapping and the hanging. He took notes while lurking in the mob and filed his story that night. “Buckner’s crime had been an awful one… and proved that this character was that of a brute,” he wrote. “Swinging so in the cool morning breeze, with the river’s bright waters rippling merrily over innumerable pebbles below, the administrators of such summary justice were fully assured that at least he would not further disturb the peace of their pleasant homes.”10

Writing two decades later, Dreiser described the lynching in one of the most disorienting and revealing passages in his extraordinary confession. “A Negro in an outlying county assaulted a girl,” he wrote, “and I arrived in time to see him lynched. But walking in the woods afterward, away from the swinging body, I thought of her.” Then, directly following the mention of the lynching of John Buckner, he continued: “If I had been alive before, now I was much more so, within my own blood and nerves. I fairly tingled all over with longing and aspiration.… Love—all its possibilities—paraded before my eyes a gorgeous fantastic and sensual procession. Love! Love! The beauty of a woman’s body.” Something about the lynching of Buckner aroused Dreiser and transformed his anxieties into optimism, his fears of sexual inadequacy into a sensation of erotic potency. His arousal seems to have captured something about the energy of the mob, the sexual energy that these white men felt as they murdered a Black man whose projected animal appetites they openly condemned and secretly desired.11

Elsewhere in his autobiography, Dreiser remembered experiencing a similar thrill on the back of a different kind of sexual violence. A friend of his named Peter McCord, who served him as a sort of Virgil of the vice world, shared with him one night the wonders of his particular fetish in “a shabby, poorly-lighted, low-ceiled” brothel where he watched a group of “absolutely black or brown girls with their white teeth and shiny eyes” dance naked while his friend played the flute. They danced, he wrote, “in some weird savage way that took me instantly to the central wilds of Africa… so strange they were.” As he wrote about it years later, Dreiser remembered sitting there for two or three hours. At first, he felt low, almost criminal. But then he began to “enjoy it intensely.” He soon began to elaborate that pleasure into a philosophy, for his enjoyment felt “anything but evil” to him. There, in the brothel, watching naked Black women paid to play out an exoticist’s fantasy, Dreiser located the germ of a new morality. “Our theology is too narrow… something we haven’t the brains as yet to comprehend.” There, in the brothel, Dreiser began his quest to imagine a moral order beyond good and evil, beyond the piebald morality of a world “dull enough to make a sacrament of marriage.” A new kind of “freedom.”12

Though Dreiser was not a great philosopher, he was a fearless ethnographer, at least of himself and his kind—the white “sports” of the city of St. Louis. What the progenitor of American “naturalism” took to be an extraordinarily complicated and unorthodox moral position—one that could lead him to understand and sympathize with a wealthy old man who traveled downtown to get sexual service from a little girl—was, in reality, a simple restatement of the practical morality of his time and the society in which he lived: the circular expression of inadequacy, entitlement, privilege, and violence we might call imperial whiteness. The license of empire.

Dreiser did not have the wit to recognize it, but there was a moral and philosophical revolution taking place in St. Louis, though it did not have to do with his fantasies of the effect on his sex life of a world where marriage was laid aside in favor of “polygamy and polyandry.” Indeed, it was happening in the very neighborhood where he lived, in the dance hall downstairs and in the music that drifted up through his window. The music Dreiser heard, unrecognizable to him but somehow still alluring and stimulating in its exotic proximity, was ragtime—the soundtrack of the emergence of modern African American urban culture.13

On Christmas Day of 1895, just a few blocks from where Dreiser had rented his small flat at the center of empire, Stagolee shot Billy Lyons in a conflict over a Stetson hat. In toasts, in tales, and finally in the famous folk song, the story of Stagolee spread throughout the Mississippi Valley and along the rail lines around the turn of the century. Ma Rainey (backed by Louis Armstrong) would sing about Stagolee, as would Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and the Grateful Dead. Stagolee is the subject of the song, but he is not its hero. In the classic version, recorded by Mississippi John Hurt in 1928, Stagolee is “cruel,” a “bad man”: “Do I care about your two babes / Or your loving wife? You done took my Stetson hat / I’m bound to take your life.” The song neither questions the wisdom of shooting a man over a hat nor celebrates the vengeance of a man so proud that he would shoot someone for touching his Stetson. It simply recites the elements of the legend: the Stetson, the .44, the wife and children, and the gallows. Stagolee was an African American legend, not a role model. He was the original gangster.14

When he shot Billy Lyons, Stagolee was in Bill Curtis’s saloon on the corner of Eleventh and Morgan in St. Louis. His government name was Lee Shelton, and he had come to St. Louis on the MKT rail line from Texas, where he was born in 1865. He was known as “Stack Lee” or “Stacker Lee” after a steamboat on the Lee Steamboat Line, which ran between Memphis and St. Louis. The ships of the Lee Steamboat Line were favored by Black passengers and also, it was rumored, by pimps and prostitutes. And indeed, Lee himself was a pimp—or as they said on the street in St. Louis, a “mack,” after the French Maquereau. When Shelton walked in, wearing a long cape over a bright blue suit, a pleated shirt, yellow calfskin gloves, and narrow-toed patent leather shoes, with a ring on his finger, a stickpin in his lapel, and a high-crowned, soft-brimmed white Stetson hat, Lyons was standing at the bar. Shelton called out, boldly, “Who’s treating?” Lyons was a substantial man himself, brother-in-law to a saloon-keeper, a Black ward boss and a tough guy. He knew Shelton, however, and bought him a drink, and the two men sat at the bar and laughed and talked.

Soon the conversation turned into an argument, and Shelton took Lyons’s bowler hat and crushed in its crown. Lyons grabbed Shelton’s hat, demanding that Shelton pay him “six bits” for his own crushed bowler. Shelton drew the famous Smith and Wesson .44 and told Billy Lyons he would kill him if Lyons did not give him back his Stetson. Lyons pulled out a knife and walked toward Shelton. “You cock-eyed son of a bitch, I’m going to make you kill me,” witnesses remembered him saying. Billy Lyons’s death certificate records that Shelton shot him in the “abdomen.” The dying man staggered toward the bar, still holding the Stetson, until Shelton snatched it from his hands and walked out of the bar. “N—r, I told you to give me my hat.”15

The neighborhood where Lee Shelton shot Billy Lyons, the neighborhood where Dreiser sojourned and fantasized about the things he could do if only he had the courage and the chance, was known as “Deep Morgan,” for the east-west street along which the barrooms and bordellos—many of them Black-owned—were arrayed. Although Lee Shelton’s house on Twelfth Street still stands, most of the structures in the architectural record of these times have been torn down and covered over. Today there is a bank on the corner of Eleventh and (what was) Morgan, just up the street from the America’s Center Convention Complex and the Dome at America’s Center, the onetime home of the St. Louis Rams football team. Morgan Street is today known as Delmar—a street name that has become a byword for segregation in the city of St. Louis. Ask anyone from the city and they will tell you: south of Delmar is white, north of Delmar is Black.

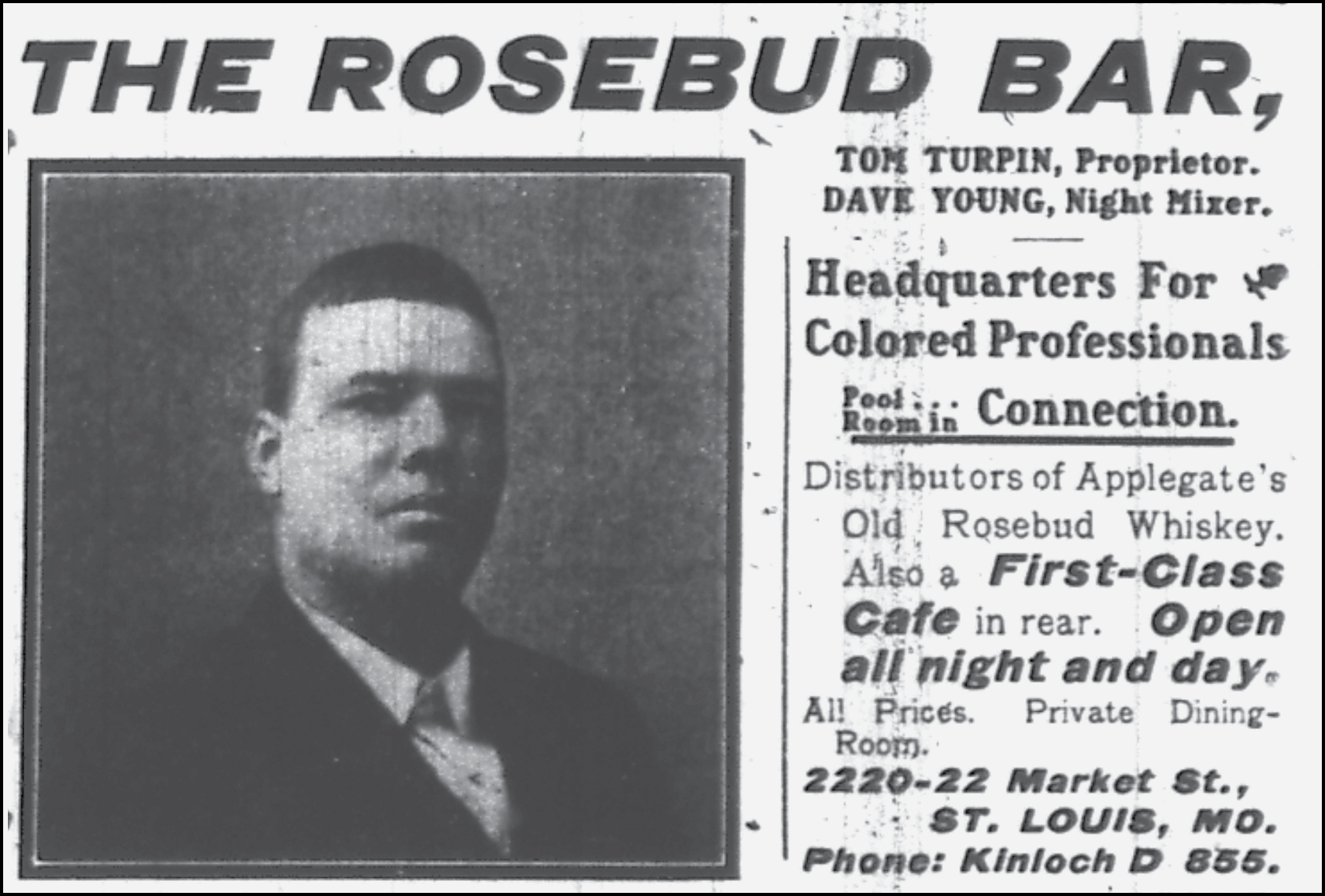

But in the 1890s, Deep Morgan was something different. Along with Chestnut Valley, the east-west corridor a few blocks to the south, Deep Morgan was the domain of pimps and prostitutes, like Lee Shelton and his best girl Lillie, but also of Black saloon-keepers and ward bosses, like Bill Curtis and Billy Lyons’s powerful brother-in-law Henry Bridgewater, who was one of the richest Black men in St. Louis and owned a saloon nearby, on the corner of Eleventh and Lucas. Henry Bridgewater’s, Bill Curtis’s Bar, the Silver Dollar, Tom Turpin’s Rosebud Bar, Madam Babe’s Castle Club, Jim Ray’s Falstaff Club, William Walker’s Alcove Café—these are just a few of the best remembered of the Black-owned clubs of the 1890s. The Black population of St. Louis had increased by 600 percent during the 1860s, and their numbers continued to grow as refugees came north to escape the sharecropping and night-riding white supremacy of the 1880s and 1890s South.16

The Black clubs in Deep Morgan and along the Chestnut Valley were sites of economic power and political organization. Men like Tom Turpin and Henry Bridgewater were property owners and emergent political bosses—participants, like their white counterparts, in the pay-to-play political world of police protection and ward-heeling machine politics. Several of the clubs served as meeting places for Black men’s social organizations, like the Four Hundred Club; others hosted ward meetings for the Republican Party and, after 1896, even meetings of Black Democrats. Some Black leaders in St. Louis, most notably James Milton Turner, became disillusioned with the city’s Republican machine; indeed, the leading historian of Deep Morgan attributes the quarrel between Shelton and Lyons to the fact that Shelton had become so frustrated with the Republicans’ inattention to the Black voters who had traditionally supported them that he had become a Democrat.17

Another St. Louis murder ballad of the 1890s (the genre can fairly be said to have originated in the city), “Frankie and Johnny,” tells the story of Johnny getting caught dancing with the wrong woman by his “sweetheart” Frankie, who had walked down to the corner to buy a bucket of beer. “Frankie and Johnny,” a love story, begins, “Frankie and Johnny were lovers / Oh Lordy, how they could love.” And it is a story of the anger of a woman who cared for her man: “Frankie and Johnny went walking / Johnny had a brand new suit / Frankie paid a hundred dollars / Just to make her man look cute.” And of unfaithfulness: “Johnny, man, a lovin’ up, That high-brow Nellie Bly” on Clark Avenue, a couple of blocks over from Chestnut. “Frankie and Johnny” tells a story about Black love in St. Louis—a certain kind of story, to be sure, about the hurting kind of love, for it ends with Frankie shooting Johnny dead with his own .44. But the ballad is a story about Black love nonetheless: about the fierce attachments between people whom the minstrel shows and “darky songs” of the day portrayed as feckless followers of fleeting pleasure. And finally, it is yet another story about a Black woman’s sexual self-possession: about Frankie keeping Johnny in clothes because they were in love and he made her happy; about Frankie refusing to allow Johnny to be in the arms of Nellie Bly, because “he was her man”; about Frankie shooting Johnny, “roota-toot-toot,” as he tried to run away, because “he done her wrong.” It is a story about the density and complexity (and fragility) of life in Deep Morgan and along the Chestnut Valley, neighborhoods for which St. Louis was famous in the 1890s, and about the lives of those who lived there and are all but forgotten today.

St. Louis was known in the 1890s as a “sporting city”—indeed, as the sporting city. For a brief period after the Civil War, St. Louis had been the only city in the United States where prostitution was legal. Under the city’s “Social Evil” laws, passed between 1870 and 1874, sex workers were licensed by the board of health and brothel-keepers paid fees that were put toward the care of “abandoned women” in the city’s Institution for the Houseless and Homeless and the treatment of the carriers of sexually transmitted disease at City Hospital. An 1871 police census found that there were over 1,200 prostitutes in the city, working out of about 150 houses. By 1894, prostitution had been outlawed for two decades, but little had changed. In that year, the city declared the entire area bounded by Market, Washington, Jefferson, and Twelfth Street—a seventy-two-square-block area—to be overrun with houses of “ill-repute.” Whatever was on the books in St. Louis in 1894, however, in Chestnut Valley and Deep Morgan—the “sporting” part of St. Louis—the law was something different. Patrolmen demanded and were provided with meals, liquor, cigars, and sex in exchange for looking the other way during periodic vice reform panics and providing protection from violent johns. “The police, the law courts, and the whorehouse with solid protection worked together,” concluded the autobiography of the sex worker Nell Kimball.18

Along with the sex trade, St. Louis was famous for gambling—poker, faro, and the numbers (also known as “the state lottery” and “the policy”). Here, too, the police took a cut, and they were frequently involved in scandals. For instance, an 1868 investigation cleared officers on the beat (not for the last time) of allegations of being drunk on duty and, in one case, riding a horse into a saloon while in uniform; sexually abusing women in their custody under the pretense of “searching” their persons; dining in the brothel of the notorious Madame Callahan; turning a blind eye to gambling and the rampant violation of the “blue laws,” which legislated the closing of barrooms, music halls, and theaters on Sundays; and standing idly by when a bull and a bear were pitted in a fight against one another for public entertainment. In the same vein, it became apparent in 1878 that the gambling interest in the city was making decisions about hiring, firing, and promotion within the police department, and in 1883 an internal investigation revealed that several members of the Police Commission had been forced to submit undated letters of resignation upon their appointment to the commission to ensure their compliance while they served. Later in 1883, the records of an investigation into police corruption that had begun earlier in the year disappeared from inside the Four Courts building downtown. St. Louis was a gangster city with a gangster police department, much of which operated as the uniformed wing of the Babylonian capitalists of the Big Cinch and the various smaller cinches that ran the demimonde in Deep Morgan and elsewhere.19

In 1882, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ran an extraordinary series of articles entitled “Where’s the Policy?” that simply listed the addresses of all the gambling houses in the city; shortly thereafter, in another series, it published the addresses of all the brothels that were hiding in plain sight, cloaked only by the impunity of police protection. In the early 1890s, Theodore Dreiser remembered, women were openly arrayed in the windows and on the porches of the “bagnio district, stretching from 12th and Chestnut to 22nd or 23rd… and girls walked the streets for hire [on] Olive Street between 6th and 12th.” For those on the outside of the game, St. Louis could be a tough place to survive. Dreiser remembered watching a “large powerful Irish policeman” on a sidewalk dragging an old woman, in the gutter, down the street by her hair, the other passers-by either “thinking nothing of it” or being “too cowardly” to intervene—a judgment that applied, unsurprisingly, to Dreiser himself. “You goddamned bitch… goddamned drunken fucking old whore,” the cop screamed as he beat her with his nightstick. Among the police, this was known as “curbstone justice.” The bluesman W. C. Handy, who spent a formative year in St. Louis, remembered the city for “the brutality of the police,” who would use yard-long nightsticks to drive vagrants off empty lots at night. For the poor and the vulnerable, the message was clear: either join the hustle and get some protection, or get out of town.20

Along with “Stagolee” and “Frankie and Johnny,” Deep Morgan was memorialized in the song “Duncan and Brady”—or, as Handy remembered it, “Brady, He’s Dead and Gone,” another of the classic murder ballads of the 1890s and a classic anthem of the fight against police brutality. The song tells the story of the shooting of patrolman James Brady in Starkes’s Tavern on Eleventh Street in the fall of 1890. The government record of the case portrays Brady’s death as the result of an ambush: drawn into the tavern to stop a fight, he was shot in the head by an out-of-control Black man, William Henry Harrison Duncan. The song remembers Brady differently, describing him as “King Brady,” a crooked cop who had “been on the job too long”; as a “big fat man,” with “a mean look in his eye,” who would “shoot somebody just to see him die”; and as a cop who tried to break up the wrong card game, a gangster cop temporarily (and fatally) out of his depth:

Well, Duncan, Duncan was tending the bar

Along comes Brady with his shiny star

Brady says, Duncan, you are under arrest

And Duncan shot a hole right in Brady’s chest

Yes, he been on the job too long

Brady, Brady, Brady, well you know you done wrong

Breaking in here when my game’s going on

Breaking down the windows, knocking down the door

And now you’re lying dead on the barroom floor

Yes, you been on the job too long

If you listen, you can almost hear how the vernacular wisdom of that refrain sounded on the street in Deep Morgan: “You been on the job too long.”21

The barrooms and bordellos in Deep Morgan and along the Chestnut Valley all employed piano players, virtually all of them Black men, to entertain their guests, and out of the crucible of imperial license, sexual longing, and artistic genius in the brothels of St. Louis came one of the definitive art forms of the twentieth century—ragtime. Johns looking for sex in St. Louis first entered a parlor where they were served drinks and met the girls. The girls themselves got a fifth of the price of the drinks the men bought downstairs, as well as a third of what they paid to go upstairs. So the music had to be right: cheery and sexy and suggestive. In the United States after the Civil War, that meant that it had to be Black. Through the 1870s and 1880s, the music played in the houses was the minstrel music of Stephen Crawford, and a generation of Black pianists began their careers playing “darky song,” which served as the background music for the for-a-fee sexual license of men like Dreiser. Scott Joplin, generally recognized as the greatest of the ragtime composers and the founder of the form (or at least the first to successfully sell it in standard notation), was one of them.22

Joplin, like Lee Shelton, had come to Missouri from Texas on the MKT. He began his musical career as a member of the Texarkana Minstrels, a quartet that performed at reunions of Confederate veterans. By 1890, he had made his way to Sedalia, a railroad boomtown in central Missouri, where the new “piano-thumping” music was starting to be played in the brothels and Black clubs along the main drag. Joplin often sat in at the Maple Leaf Club, where he began to bend the phrases through which minstrelsy had represented the arrival of a Black character onstage into a new sort of music. The music Joplin played was insistently syncopated: it separated the beat played in the bass clef from that played in the treble, creating novel depth and counterpoint within each piece. Where the bass maintained the continuous 4/4 (or, less frequently, 3/4) tempo of the popular music of the era, the treble sped and slowed polyrhythmically and discontinuously. Although there was syncopated music before ragtime (musicologists often point to several bars of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, Op. 111), it was from Joplin and the pianists he met, played with, learned from, and influenced in St. Louis that the characteristic ragtime rhythm of modern jazz and the blues emerged.23

In the 1890s, the city of St. Louis was known as a “sporting city”—an “anything goes” city of players, pimps, and prostitutes. The city’s nightlife supported a number of Black-owned bars and a rich musical scene out of which ragtime music emerged. (State Historical Society of Missouri)

In the 1890s, Joplin took the MKT back and forth from Sedalia to St. Louis, where he played in the clubs in Chestnut Valley and along Market Street. The piano player Charles Thompson recalled that Joplin and his fellow player and composer Louis Chauvin “had a string of followers as they strutted about the district,” remembering that “when Joplin returned for a visit there would be just like a parade down Market St.” They played at the Silver Dollar Saloon, where Tom Turpin, a man so large he could not sit down at the piano, and the composer of the genre-defining “Harlem Rag” in 1892, presided behind the bar.24

W. C. Handy remembered that Black quartets from all over the nation, his among them, gathered in St. Louis in 1892. Many of them, including Handy, had first traveled to Chicago, intending to be there for the World’s Fair. On arriving, they found that the fair had been postponed for a year, and so, rather than staying in Chicago, they moved on to St. Louis, whose sporting reputation promised more opportunities for musicians. By the mid-1890s, the city was crowded with musicians. In fact, by the time Joplin started traveling to St. Louis, he sometimes had a hard time finding a piano to play. So deep was the talent in the barrooms and theaters along Chestnut Valley that one of the nation’s most renowned musical innovators, however talented as a composer, found that he did not have the technical ability to hold his place on the stage. It was in St. Louis that Handy—who was sleeping rough in a vacant lot at the corner of Twelfth and Morgan, a block up the street from where Billy Lyons would shortly meet his untimely end—first heard the music that he said inspired the rhythms of the blues.25

Ragtime, which took its name from the ragpickers at the edge of the city’s economy, sounds bright and colorful on the topside and is usually propelled by a rolling, oblong stride in the bass. Sometimes, as in Joplin’s most famous pieces, “The Maple Leaf Rag” (1899) and “The Entertainer” (1902), the bass seems to lead into and support the treble. In others, like “A Real Slow Drag” from Joplin’s 1911 opera Treemonisha, the bass and treble almost seem to work at cross-purposes as the bright melody is insistently pulled back by the heavy, repetitive bass line. Common to all the songs is a play of surface and depth, of lines diverging from one another and then coming back together, of the insistent tinkling melody pushing out to the front and then being called to account by the implacable rolling bass—the way Lillie Shelton and Lee Shelton might have looked as they walked down the street together, or the way Frankie and Johnny loved and the undertow in her love that would never let him go. Joplin wrote the soundtrack for desire and dread, for the inflated festivity of the night before and the pounding payback of the morning after, for pleasure rung out of pain, for the hard work that subtended the easy life. For the rumble and the bell of the streetcar that carried the wealthy white men of the West End downtown to Chestnut Valley and Deep Morgan.26

Beginning in 1889, the first electric streetcar in St. Louis ran along Lindell Boulevard, from the middle of downtown out to Forest Park, where the rich people lived. It was a sensation at the time and even found its way into the song “Duncan and Brady.” Middle-class whites began to move out to the West End and use the cars to commute into the city to work; it was in these years that “inner-ring” suburbs such as Webster Groves, Maplewood, and Shrewsbury were incorporated. Suburbanization transformed the geography of domestic service and white supremacy (not to mention sexuality) in the city. To this day, St. Louis is a city of alleyways—small service roads bisecting residential blocks along the backsides of the lots. In the years after the Civil War, as the population of the city expanded, people crowded into these alleys and built small shanties that housed the cooks and cleaners and child-minders who staffed the pleasant outward-facing, street-numbered houses that they entered only through the back door. It was in these alleys that Theodore Dreiser sought out the thick, teeming life of lumpen and working-class St. Louis. But as wealthy and even middle-class whites moved out to the suburbs, from which they took the streetcar into work, their domestic servants—largely though not exclusively African American women—began to take the streetcars out from the city to work in the suburbs. Increasingly, the ad hoc pattern of squatter settlement in the alleyways was regularized into a new pattern: real estate “development” in pursuit of rent from working-class tenants.

Refugee squatters were transformed in the years around the turn of the century into renters. The city also passed its first segregation ordinance at this time, in 1901, forbidding Black St. Louisans, by popular referendum, from establishing a residence on any block that was at least “seventy-five percent white.” Streetcars, suburbs, and segregation reformatted the space of racial capitalism in St. Louis—both the real estate market and the daily rituals of white pride and preferment in the city. There was value in segregation, surcharges imposed for both the whiteness of the suburbs and the racial reservation—the bounded areas of Black St. Louis.27

And where there was money to be made in St. Louis, there was corruption. In an urban replay of the imperial corruption of racial capitalism and the railroad, St. Louis at the turn of the century was the most outrageously and notoriously corrupt city in the nation—the city of “the boodle,” a single word denoting both the practice and the take. In 1902, muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens wrote an essay on St. Louis for McClure’s that became the introduction of his landmark account of urban political (and police) corruption in the United States, The Shame of the Cities (1904). A year later, amazed at how brazenly the city’s elite kept up the vote-buying and boodling even after a bright light had been shined into their backrooms, he wrote a follow-up essay about the city, “The Shamelessness of St. Louis.”28

St. Louis, according to Steffens, announced itself to the world as “the worst-governed city in America,” a city where the leading men were single-mindedly engaged in a ravenous competition to “devour their own city.” Even as the central core of the city presented a portrait of urban decline—taps oozing muddy water (“too thick to drink, too thin to plow,” Mark Twain famously dubbed the water in the city); “poorly paved, refuse-burdened streets”; and “dusty or mud-covered alleys” in back of crowded “fire-trap” tenements—the city’s businessmen and politicians were busy selling off its future. And the corruption followed from the vice. The city government was so full of saloon-keepers, Steffens remarked, that an old joke had it that city hall could be emptied by hiring “a boy to rush into a session and call out, ‘Mister, your saloon is on fire!’”29

According to Steffens, everything in St. Louis politics—every franchise approval, every property easement, every vote in favor, every vote against—had a price. “There was a price for a grain elevator, a price for a short switch; side tracks were charged for by the linear foot, but at rates which varied according to the nature of the ground taken; a street improvement cost so much.… As there was a scale for favorable legislation, so there was one for defeating bills.” And the biggest hustle of them all: the fraudulent sale of the suburban railway to its only competitor, the St. Louis Transit Company—a sale that promised its principals millions in return for what turned out to be the $144,000 it took to buy the St. Louis city council.30

The occasion for Steffens’s piece was a years-long investigation of municipal corruption led by a maverick district attorney named Joseph Folk. Over the course of several years beginning in 1904, Folk investigated a rolling set of conspiracies between local businessmen, bankers, and political leaders to buy and fix virtually every matter that came before the St. Louis city council. By the end of Folk’s time in office, a cross-section of the city’s elite had either gone to jail or fled to Mexico, and he had been propelled to national prominence as “Holy Joe,” the governor of Missouri, and the paladin of the “Missouri Idea,” which became the inspiration for much of the Progressive emphasis on “good government” over the first decade of the century.31

The occasion for Folk’s crusade was, as Steffens noted at the beginning of his first essay in McClure’s, the city’s bid to host the 1904 World’s Fair—the grand scheme of the city’s elite to turn the nation’s sporting city into the global archetype of modern civilization. By 1890, St. Louis had slipped a place in the rankings behind Chicago, but was still the fifth-largest city in the United States. The city had the largest train station, brewery, chemical plants, brickworks, and electric plant on the continent. After mounting an unsuccessful bid to host the Columbia Exposition, which had gone off in Chicago in 1893, St. Louis succeeded in securing the 1904 fair, which was promoted as a celebration of the one hundredth anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase and organized by a board of local luminaries and philanthropists—eleven of the twelve were members of the Veiled Prophet organization—and headed by David Francis, the grand oracle of the Big Cinch, the boss of bosses. Seldom in the history of the world had there been (and rarely has there been since) such a gathering of professional racists, keepers of human zoos, and Western civilizational luminaries as there was in Forest Park and on the campus of nearby Washington University during the summer and fall of 1904.32

The conventional estimate is that 20 million people attended the fair, which began when Theodore Roosevelt pushed a gold button in the White House and instantaneously illuminated the fairgrounds eight hundred miles away in Forest Park. Because tickets to the fair were sold in books and visitors often went more than once (sixteen-year-old St. Louisan T. S. Eliot, for instance, used all but one of the fifty tickets in his own book, which is preserved today at the Missouri Historical Society), that number surely overstates the attendance figure. Nevertheless, the figure of 20 million entrances (as opposed to entrants) gives some idea of the terrific scale of the seven-month-long fair—it works out to just under 100,000 entrants a day in a city of around 600,000 inhabitants. On the weekends, a train a minute left Union Station for the fairgrounds.33

During the fair, something like 20,000 people lived and worked in 1,500 buildings scattered across the 1,300 acres of Forest Park. The same 264-foot, 4,200-ton, 2,000-horsepower Ferris wheel that had dominated the skyline of the Chicago fair now seemed small in St. Louis, where the fair was more than twice as big. The Ferris wheel had been transported at a cost of several hundred thousand dollars and the lives of nine men who died during its reassembly. The Liberty Bell, never loaned for exhibition before or since, was escorted from the rail depot to the grounds by a parade of 75,000 schoolchildren. One exhibit boasted dozens of babies living in incubators, who were rotated out into cribs as they became healthy enough to survive without intensive support. A 900-foot indoor whirlpool pumped 49,000 gallons of water (drawn from the Mississippi) per minute. A nine-acre reconstruction of the Tyrolean Alps, sponsored by the beer baron Adolphus Busch, hosted performances of the famous Oberammergau Passion Play, a reproduction of Mozart’s Salzburg birthplace, and a café that seated 2,500 at a time. An eleven-acre reconstruction of Jerusalem and the Holy Land included reproductions of the stable where Jesus was born, the Garden of Gethsemane where he was betrayed by Judas, and the Temple of the Mount, where Mohammed ascended to Paradise. Visitors could see Ulysses S. Grant’s St. Louis County log cabin and the train car that carried the assassinated Abraham Lincoln from Washington, DC, to his burial place in Springfield, Illinois. They could admire Jim Key, the educated horse who could spell, sort mail, make change, and remove a silver dollar from a glass jar without spilling (or drinking) a drop of the liquid inside. They could tour a transplanted California ostrich farm. They could dine on hot dogs, hamburgers, cotton candy, peanut butter, ice cream cones, and Dr. Pepper, all of which are credibly said to have been invented (or at least introduced as mass-market staples) on the grounds of the 1904 fair. As a sort of sideshow, St. Louis also hosted the Olympic Games, which were held on the adjacent grounds of Washington University during the summer of 1904. At the center of the grounds stood the Column of Progress, a ten-story classical set piece festooned with eagles and topped with a figure of Progress standing astride a giant garlanded globe.34

Combined with the fair and organized in coordination with Washington University was a series of academic events aimed at presenting, in the words of the German psychologist Hugo Münsterburg in his opening address to the International Congress of Arts and Sciences, a “Weltanschauung” for the new century: “a unified view of the whole of reality.” Münsterburg’s collaborator in industrial psychology, Frederick Winslow Taylor, who would publish The Principles of Scientific Management in 1911, was also at the fair, as were the pioneering German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies, with whom originated the theoretical distinction between society (gemeinschaft) and community (gesellschaft); the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, whose “frontier thesis” shapes the study of the United States down to the present day; and the German economist and activist Werner Sombart, who would publish “Why No Socialism in the United States?” in 1905. Also in attendance were Woodrow Wilson, the Johns Hopkins historian who would soon become president of the United States; the historian Henry Adams, the author of a nine-volume history of the early republic and, later, of one of the most famous memoirs in American letters; the philosopher, mathematician, and historian Josiah Royce; and G. Stanley Hall, the eugenicist first president of the American Psychological Association and promoter of the notion that the races of man followed a course of development analogous to those of individual human beings—from infancy and childhood to adulthood and senescence. Max Weber, who published The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism in 1905, made his first public appearance at the St. Louis World’s Fair, following a five-year nervous breakdown. Mark Twain and Henry James sat down for dinner together at the fair, although both seemed depressed to observers and their much-anticipated conversation has gone unremembered. The teenage T. S. Eliot, we have seen, toured the grounds repeatedly, as did Thomas Wolfe, who remembered the fair in his lugubrious masterpiece Look Homeward, Angel; Frank Lloyd Wright, who first encountered Japanese architecture at the fair; and Kate Chopin, who collapsed and died after a humid 90 degree day at the fair in August 1904. On the closing day of the Congress, the mathematician Henri Poincaré delivered a critique of Newtonian mechanics that provided the intellectual foundation for Einstein’s 1905 papers outlining the equivalence of mass and energy and the special theory of relativity. Nearby, in the Hall of Technology, a cube of Ernest Rutherford’s radium glowed uncannily through the summer and into the fall. During the summer of 1904, St. Louis was not simply the hub of the nation’s western empire—it was the center of the world.35

And yet it was the city’s own imperial history and aspirations that framed the fair. The discipline that presided over the fair was neither psychology nor sociology, nor even physics, but anthropology. Prospero more than Prometheus was the spirit that prefigured the World’s Fair in Forest Park. Like the rest of the exhibits on the grounds—like the baby incubators on the midway (“the Pike”), the miniature railways, the motorized airships, the X-ray machine, and the world’s first air conditioner and player piano and cordless phone and wall plug and fax machine and answering machine—the world’s intellectuals were self-consciously positioned by organizers to make a point about history and civilization. “Over and above all the fair is the record of the social conditions of mankind,” wrote Frederick Skiff, the director of exhibits, “registering not only the culture of the world at this time, but indicating the particular plans along with which different races and different people may safely proceed, or, in fact have begun to advance towards a still higher development.” The purpose of the fair, in the words of David Francis, the chief executive of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Corporation, was to demonstrate to visitors that human history had reached its “apotheosis” in Forest Park. Were all the works of prior civilization to be blotted out, he concluded, the records of the fair would provide the “necessary standards” for its rebuilding.36

In Forest Park in the summer of 1904, the directors of the exposition’s Anthropology Department, including the founder of American cultural anthropology, Franz Boas, presided over the assembly of the largest human zoo in world history. An estimated ten thousand people were conscripted to play a role in the account of progress by the Anthropology Department. Brought to St. Louis for the fair, they lived for its duration on the grounds and were exhibited in ersatz reconstructions of their “native habitats” for curious visitors to Forest Park. Among them were Ainu people from Japan, “Patagonians” from the Andes, and members of fifty-one of the First Nations of North America—including Chief Joseph of the massacred Nez Perce, the Comanche soldier Quanah Parker, and the Apache leader Geronimo. Geronimo was assigned to pose for nickel-apiece souvenir photographs with white visitors and play the part of the Sioux leader Sitting Bull in daily reenactments of the Battle of the Little Bighorn.37

Elsewhere on the grounds lived Ota Benga, who had been sold along with seven other people to the American Samuel Verner, who had traveled to King Leopold’s Congo Free State under the auspices of the fair’s Anthropology Department to purchase Mbuti “pygmies” with the sole purpose of exhibiting them at the fair. Benga, who was about twenty at the time of his sale, had had his teeth filed into sharp points as a child, and was exhibited at the fair as a “cannibal.” Benga and the other enslaved Africans sometimes danced and performed before as many as twenty thousand people at a time. For a time after the fair, under the auspices of the white supremacist racial theorist Madison Grant, Benga was kept in a cage at the Bronx Zoo. After his release, Benga worked in a tobacco factory in Virginia, where he began to wear Western clothes and had his teeth capped. In March 1916, in Lynchburg, Virginia, Ota Benga built a large fire, danced, and then shot himself through the heart.38

These terrible, soul-warping images were designed to be that way: the fair intentionally produced instrumental images of Geronimo, Ota Benga, and other people of color that would be suitable for deployment in a larger argument about white supremacy and the pathway to racial progress. “There is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” wrote Walter Benjamin in what might be seen as an evaluation of the savagery with which the organizers of the fair assembled living human beings in a zoo as a testimony to their own advanced position in the “march of human progress.” The historical record of the fair tells us much more about people like David Francis and Franz Boas than it does about people like Geronimo and Ota Benga.39

The forty-seven-acre “Philippine Reservation” in the southwest corner of the fairgrounds was the 1904 fair’s ideological core as well as its most popular attraction—ninety-nine out of a hundred visitors to the fair visited the reservation, estimated Francis. Although the US war against the Philippines had officially ended in 1902, American troops were still fighting insurgents on several of the islands of the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine exhibit in St. Louis was, at once, a celebration of conquest, an operation in an ongoing counterinsurgency campaign, and an argument about why the first two were necessary actions taken in the support of racial civilization and social progress. The War Department, with the support of William Howard Taft, the US military governor of the Philippines, coordinated the collection and transport of the one thousand eventual inhabitants of the Philippine Reservation, as well as of the battalion of Philippine Scouts—four hundred US-aligned Filipino soldiers, who served under white officers. The fair, Taft argued, would exert “a very great influence on completing the pacification of the Philippines” by creating a cadre of Filipinos who would be informed about the wonders of modern civilization and overawed by its inexorability. The Philippine Reservation was, one could argue, a civilizationist psyop—an act of psychological warfare.40

Visitors to the Philippine Reservation entered through a “Walled City” meant to recall the fortification of the conquered city of Manila. Arrayed around the grounds were villages populated by various officially designated ethnic “types,” who were themselves categorized according to their supposed level of civilization: the “intelligent” Visayans; the “fiercely” Islamic Moros; the “savage” Bagóbo; the “monkey-like” Negritos, one of whom came to be known as “Missing Link”; and the “picturesque” Igorots. Camped around the edges of the Reservation, beyond the ersatz ethnic enclaves, were the Scouts, who were charged with keeping order inside the Reservation and exemplifying the final stages of the civilizing process.41

Like the Philippine Reservation, the human exhibits at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition were arranged spatially in a way that was meant to tell a story about racial progress. The idea was as destructively simple as it was sadly familiar: all of human history marked linear progress from less to more civilization, and the middling races—the Igorots, if not the Negritos—could be molded to become productive members of civilized society. In other words, they could be turned into workers. “There is a course of progress running from lower to higher humanity, and all the physical and human types of Man mark stages in that course,” wrote William McGee, the leader of the fair’s Anthropology Department and the man termed the “overlord of the savage world” by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.42

That the Philippine Reservation was called a “reservation” in the first place reflected an important fact about the racial imagination of the fair organizers. In their view, the specific imperial history of the American West—the history that began with the Lewis and Clark expedition—provided the model for the future of the American empire and the world more generally. The legacy of conquest was celebrated throughout the park, in both the massive statuary of noble savagery—Cyrus Dallin’s Sioux Chief being exemplary in this regard—and the daily restaging of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. But the overriding message of the fair was about consigning the “savage” past to the future progress of “civilization.” The “method” of the Anthropology Department, according to McGee, was “to use living peoples in their accustomed avocations as our great object lesson… to represent human progress from the dark prime to the highest enlightenment.” In McGee’s vision, the Louisiana Purchase had begun the “purposeful… promotion” of Indians into American citizens. Slowing that down and spinning out the implications, we can see that McGee was proposing the “civilization” of Native Americans—the process of conquest, annihilation, subordination, sequestration, and reeducation that had begun with the Louisiana Purchase (this was the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, after all)—as the model for global racial governance.43

And at the center of this vision of global, imperial human progress was the Indian school model of Schurz and Pratt—“America’s best effort to elevate the lower races… savages made, by American methods, into civilized workers.” The Louisiana Purchase Exposition stood at the juncture between Indian wars and overseas imperial ambition, translating the supposed successful culmination of the former into an open-ended justification of the latter. The idea behind the fair was that civilization—racial progress—could take the place of violence as the principal tool of empire, or as one US general put it about the war in the Philippines, “The keynote of the insurrection”—the lesson to be learned—“is not tyranny, for we are not tyrants. It is race.” In the eyes of the organizers in the Anthropology Department, as in the words of General Douglas MacArthur (the military governor of the Philippines and father of the more famous General MacArthur who would lead American soldiers in the Pacific Theater of the Second World War), the fair was to be, like the Philippines itself, a “tuitionary annex” of the United States—a school for civilization.44

There was no room at the fair for a story about African American racial progress. The imperial notion of racial malleability and improvement was twinned with a Negrophobic belief in the implacable inferiority of African Americans. The very same Black soldiers who had served as imperial adjutants in the Indian wars, the Spanish-American War, and the Philippine-American War—which were endlessly replayed as the historical backstory of the 1904 fair—were not allowed on the grounds in uniform. All of the fairground restaurants were segregated. Plans for a building celebrating the advances and achievements of American Blacks were broached, but never materialized. The plan for a single “Negro Day” at the fair was eventually canceled, and a speaking invitation to the ex-slave, educator, and up-by-your-bootstraps conservative Booker T. Washington was withdrawn. The only representation of African Americans on the fairgrounds was at “the Old Plantation,” where Black actors tended a garden, staged a fake religious revival, sang minstrel songs, and cakewalked in an endless loop of white racial nostalgia. And though Scott Joplin composed “The Cascades” as a comment on the famous waterfall at the center of the fairground, ragtime music was banished from the grounds. Not only was ragtime a genuinely avant-garde challenge to the beaux arts classicism that provided the backbone of the fair’s aesthetic vision, but its syncopated, polyrhythmic tempo implicitly challenged the linear developmental time of the fair’s presentation of human “progress.”45

The fair provided many opportunities for visitors to insert themselves into its overarching account of racial time. They could, in time-honored fashion, gawk and chuckle at the way other people in the world lived; they could even riot when those other people refused to perform for them, as happened when the crowds threw rocks at the small houses in which Ota Benga and his fellows took shelter when the weather got cold. While marveling at the technological wonders that attested to the ingenuity of their moment in time, they could cast a nostalgic backward glance at the simpler lives led by the human creatures on exhibit. They could draw sharp distinctions between the savage and the civilized based on how they washed and dressed themselves and on what they put into their bodies—the rumor that some of the denizens of the Philippine Reservation ate dogs provided one of the most durable memories of the fair in St. Louis. To this day one of the neighborhoods near the long-gone exposition grounds is called “Dogtown,” because it is supposedly where the Filipinos got their dogs. White visitors to the fair had their heads measured (“cephalization”) and their manual dexterity and sensory perception tested (“sensitization”), the emergent racial theory’s key determinants of civilizational progress.46

In a city where one-fifth of the population was foreign-born and twice that many again had parents who were, the fair offered a powerful argument about the solvent character of imperial whiteness. It offered a dirty bargain to the working whites in a city with an enduring strain of labor radicalism: over two hundred stoppages and strikes had disrupted the preparations for the fair, and a property-protecting posse of hired guns in the service of capital had opened fire on a workingmen’s parade only four years earlier. Come spend a day enjoying yourselves, the fair beckoned; lay down your placards and your pistols, and take up your rightful place in the front rank of the civilization and the “march of progress.” The exhibits at the fair were explicitly designed, in the words of David Francis, to teach the “working citizenry” of the United States (another of the fair’s boosters less delicately termed its intended audience the “unlearned” and “unlettered”) “about the proper classification, correlation, and harmonization of capital and labor”—about capitalism as a form of racial progress. The fair exhibits were designed to domesticate the restive immigrant workers of St. Louis by turning them into white people.47

The Igorot village held a peculiar fascination for white fairgoers. From the moment the Igorot arrived in St. Louis, their near-nudity was a topic of debate. Local moralists feared the effect of so many naked and dark bodies on white women who visited the fair. Government officials, including Taft, worried that the nudity on the Reservation might undermine the case they were trying to make about the success of the civilizing mission of the United States in the Philippines. The leaders of the Anthropology Department, including Boas, argued that the ethnographic value of the exhibit would be destroyed if its inmates were dressed up like bankers or butlers or, as one of them put it in a letter to Taft, “plantation n—s.” The question of the properly exotic and yet minimally erotic way to clothe the inhabitants of the federally sponsored human zoo was eventually decided by the president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, who reasoned that the stringed codpieces worn by the men in the villages could be draped with loincloths that covered their buttocks and bulges without essentially compromising the realism of the exhibit or its ability to convey the intended message about both the savage simplicity of the Igorot and their ultimate (under the proper imperial tutelage) human improvability.48

A photograph taken by Jessie Tarbox Beals, preserved today in the Missouri Historical Society, a short walk away from the place where it was taken, suggests some of the source of the anxiety. Entitled “Mrs. Wilkins, Teaching an Igorrote-Boy the Cake Walk,” the image portrays a white woman and an Igorot boy. Dressed in a long white dress, she is lifting the hem with her left hand while reaching out to the boy with her right. He wears a loincloth, a necklace, and a top hat and holds a long thin stick like a baton in his right hand; his left hand, grasped by the woman at the wrist, is arrested, dead-center in the photo, offered, intercepted, and only half-accepted. They stand nearly side by side, the woman just a tiny bit behind and seeming to be stepping in time to the call of an unheard tune. They are laughing. The photograph portrays a moment of human contact, even intimacy, between two people from different worlds—or, as the fair would have it, different times.49

Like most any photograph, the image elides the circumstances of its own production, most notably the imperial violence that was the essential condition of its existence. It reframes the historical violence that brought the boy to St. Louis and confined him to the grounds of the fair as a lighthearted moment shared by people from two different places in time. And with the Cake Walk, a minstrel show staple, patterning their common steps, this momentary connection between white and brown is also framed in the dominant idiom of US anti-Blackness. And yet, all that said, the two figures are laughing as they stand there together. And that could be threatening.50

The St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904 sought to link the city’s prominence in the history of continental imperialism to future leadership in the imperial management of the globe. The fair featured the largest human zoo in the history of the world and was characterized by an undercurrent of doubt about white women’s sexual desire and self-possession. (Missouri Historical Society)

“Meet Me in St. Louis,” the unofficial theme song of the 1904 fair and one of its most widely remembered artifacts, tells the story of a white woman named Flossie, who cleaned out her closet and abandoned her man to go to the fair. “Meet me in St. Louis, Louis,” reads the note that she left him, which provides the song’s chorus, “Meet me at the fair… We will dance the Hoochee-Koochee” / I will be your “tootsie-wootsie / If you will meet me in St. Louis, Louis / Meet me at the fair.” The promised “Hoochee-Koochee” was a reference to the national sensation caused by the dancer Fahreda Mazar Spyropoulos, who, under the name Fatima, danced at the Columbian Exposition in 1893 so suggestively that she was banned from the St. Louis World’s Fair. The “hoochie-coochie” was a racially tinted sexual promise. The song goes on to suggest just how far Flossie might go once she makes it to St. Louis:

There came to the gay tenderloin,

a Jay who had money to burn,

The poor simple soul

showed a girlie his roll,

and she said, “for some wine dear, I yearn.”

A bottle and bird right away,

she touched him then said, “I can’t stay.”

He sighed, “Tell me, sweet,

where can you and I meet?”

and the orchestra started to play

The theme song of the 1904 fair was a song about a white woman gone sporting in St. Louis: about the allure of interracial desire and the dark pleasures of the tenderloin that might draw in a young white woman beguiled by the bright fair lights. And about a white man who lost control of his girl.

On July 3, 1904, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch framed the interracial imperial fascination that haunted both “Meet Me in St. Louis” and the photograph of “Mrs. Wilkins” as a threat to racial purity. “Filipinos Become a Fad with Foolish Young Girls,” read the headline. Later in the week, a group of visiting schoolteachers invited some of the Philippine Scouts to escort them around the grounds. As they walked the grounds, whites in the crowd began to yell at the Scouts, calling them “n—s.” The Jefferson Guards—the all-white private police who patrolled the fairgrounds, many of them veterans of the Philippine-American War—gathered and threatened to arrest the Scouts and any of the teachers who continued to stand there with them. Some uniformed US Marines, visitors to the fair, joined the Jefferson Guards in harassing the Philippine Scouts, and a riot ensued. Subsequent reports suggested that as many as two hundred Scouts had faced off with as many whites on the Pike, near the entrance to “Mysterious Asia.” Even after the Scouts made their way back to the Philippine Reservation, the paramilitary park police pursued them, firing guns in the air and threatening to burn the Reservation: “Come on boys, let’s clean the[m] off the earth!” Two weeks later, six white women and an untold number of Scouts were arrested on the Reservation following another riot at the Café Luzon.51

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition was an effort to codify the history that had begun with Lewis and Clark—the history of nineteenth-century St. Louis and the imperial project it sponsored—into a set of lessons that would guide the United States in the twentieth century. It was, in the words of one of its boosters, a “University of the Future.” In that way, if in few others, the fair resonated with the work of W.E.B. Du Bois (officially suppressed on the fairgrounds), who had written in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.” It was against the backdrop of the St. Louis World’s Fair that President Theodore Roosevelt, the former Rough Rider and the biographer of Benton, announced his corollary to the Monroe Doctrine while touring the grounds in November. Henceforth, the United States would reserve the right to intervene in the internal affairs of nations anywhere in the Western Hemisphere. The United States, he explained metaphorically, would be the hemisphere’s “policeman.” The racial and sexual order that prevailed in the city of St. Louis and on the Pike at the World’s Fair was to be generalized as a principle of international order. Perhaps with the proper guidance, and under the proper constraints, the subjects of the racial and sexual order—women, workers, the darker races of the world—could learn to like it.

The World’s Fair of 1904 was a sanitized and idealized projection of the self-regarding fantasy life of the city’s ruling class and their intellectual and cultural collaborators from all over the world. It tried to channel all of the violence, steamy desire, and brittle masculine anxiety that characterized both the history of the city and its daily life into a set of pat lessons about white supremacy and racial progress. The fair was designed, at bottom, to pacify the city’s white workers and ensure their proper alignment with the course of freedom-through-capitalism and imperial progress. It was designed, that is, to direct the attention of white workingmen to all of those who were below them on the ladder of civilization and away from those who presided over them from within glassed-in offices above the factory floors where they worked to earn the cost of a day’s entrance to the fair. The proof of civilization that sustained the fair and made it materially possible was wrung out of their aching bodies in those factories—not only the machines and products exhibited on the midway but also the economic surplus necessary to the creation of something as grand and frivolous as a disposable material parable about the entirety of human history built out over hundreds of acres of forestland. The mixture of white entitlement and labor discipline, however, was an unstable compound, volatile and likely to explode.