8 | NOT POOR, JUST BROKE

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

—MAYA ANGELOU, “Still I Rise”

THE FIRST PANEL OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN PAINTER JACOB Lawrence’s masterpiece visual history of the Great Migration depicts southern Blacks lining up to buy northbound train tickets in a crowded station. Along with ticket windows for New York and Chicago, Lawrence included St. Louis as the third emblematic Black metropolis of the migration. Tens of thousands of Blacks migrated to the city, joining the refugees from East St. Louis, in the years between the world wars. They came in search of sanctuary from the white supremacist violence of the Deep South, of honest wages instead of sharecropping contracts and company stores, of the chance to vote, and of the hope of something closer to freedom. Hope was enough to carry them north on a train traveling up the line to Union Station. But, after that, they had to fight for everything—not just for their dreams, but for their basic right, as citizens of the United States, as working people, as human beings, to the bare subsistence required to keep them alive, to living where they wanted, and to their children having safe places to play, to learn, and perhaps even to flourish. In the years between the world wars, the proportion of African Americans in the city’s population almost doubled (to over 13 percent, about 100,000 people) as migrants from the South added their energy, creativity, and courage to the city’s existing tradition of Black resistance and radical struggle and pointed the way forward to a brighter, more equitable future for all residents of St. Louis. Many were lost along the way, but their struggle persists down to the present day.1

On February 29, 1916, the city of St. Louis became the first in the nation to pass a residential segregation ordinance by popular referendum, part of a wider panic about Black refugees from the South in the first decades of the century. The ordinance was sponsored by a long list of real estate commercial interests and white neighborhood associations that came together as the Universal Welfare Association. It stipulated that no Blacks should move into neighborhoods where either 100 percent of the houses were owned by whites or 75 percent of the residents were white. The ordinance also banned whites from moving to neighborhoods in which the opposite set of circumstances prevailed. The ordinance’s defenders claimed that its intent was not prejudicial, but rather mutually beneficial. “Our ordinance protects both the Negro and white man where he lives now,” said the Universal Welfare Association in an early instance of the employment of false equivalence in the service of white supremacy. For, as everyone knew, the white supremacist and racial capitalist origins of the proposal were its chief selling point. “There has been for years a constantly increasing protest against the encroachments of Negroes moving into white neighborhoods, especially new, bright, and attractive neighborhoods built up by the home owners and paid for out of the hard earning of our representative thrifty, frugal, and home-loving people,” the realtors began, before coming to the point. White St. Louis was under siege: “There have been over 1,000 actual cases of Negro invasion,” mostly to the detriment of “widows and dependents.” Although it was opposed by the newspapers in the city—white and Black—the segregation ordinance was passed by an overwhelming majority of the voters (African American voting rights prevailed in St. Louis, but Blacks in the city were wildly outnumbered in the early years of the century) and became law in the spring of 1916.2

The US Supreme Court’s 1916 decision in Buchanan v. Warley, a case that held that a Louisville ordinance very similar to the one in St. Louis violated the “equal protection” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, put an end to the segregation ordinance, but not to its replication in various forms that persist down to the present day. Among white homeowners, there was (and is) an apparently unshakable belief in direct connections between the race of the inhabitants of a neighborhood and the value of the homes in that neighborhood—a belief powerful enough to transform itself into a social fact. By midcentury, realtors, city planners, and white homeowners would find ways of making the case for segregation in language that was almost completely devoid of overt allusion to the racial character of the wealth that was being protected. In the meantime, however, the neighborhood associations, which had been so active in supporting the segregation ordinance, turned to what became the dominant tool for realizing the extra increment of value to which they believed their whiteness entitled them: the restrictive covenant. Indeed, given the degree to which St. Louis was still a city of immigrants and the children of immigrants, the covenants might be seen as a way of whitening the city, of urging immigrant Germans, Scandinavians, Russian and Polish Jews, and others to declare for whiteness. In the period between the segregation ordinance and the US Supreme Court’s 1948 decision in Shelley v. Kraemer, which held that racially restrictive covenants were not legally enforceable, Black St. Louis was surrounded and closed out by almost four hundred specifically covenanted white neighborhoods.3

The frontier of racial residence ran along Grand Avenue and produced value for the whites who owned the majority of the property on both sides. On the west side of the line, white homeowners and rentiers received a subsidy in the form of a guarantee that no prospective buyer or renter need ever worry about having a Black neighbor, with a corresponding boost to the value of their property. To keep up the covenants, the realtors turned to maudlin stories of widowed old ladies who needed to be protected, lest they be unable to rent their rooms to whites who would not live next door to Blacks (these old ladies apparently preferred to face foreclosure than to rent to Blacks), and maiden aunts who would be divested of half the value of the house they had saved their entire lives to buy if a Black family moved in next door. But the message on the flip side of these fears was also quite clear: whiten your block and your house might double in value.4

On the east side of the line, segregation produced housing scarcity, making Black migrants easy money for white landlords. And as the population of Black St. Louis grew through two phases of Black migration from the South in the years between 1910 and 1950, its geographic outline (tall tales of “Negro invasion” notwithstanding) remained roughly the same. Rather than expanding, the social and familial life of Black St. Louis was compressed into an area whose population density varied between 200 and 400 percent of that prevailing in much of white St. Louis. Apartments were subdivided into the kitchenettes that became characteristic of how postmigration Blacks lived: the familiar four-family St. Louis brick apartment building was cut up on the inside to accommodate twelve or even sixteen families in two-room apartments, with one room for cooking and eating and one for sleeping, and with no running water, indoor toilets, or reliable heat. The comedian Dick Gregory later recounted a childhood story of slamming the door on a white lady bearing a Thanksgiving-gift turkey, not because he hated turkey or Thanksgiving or even well-meaning white ladies, but because his family’s apartment did not have an oven in which the bird could be cooked.5

All that segregation and compression was money in the bank for the white landlords who owned the buildings. The artificially created housing shortage enabled landlords to charge higher rents—contemporary estimates of the “Black tax” in rental property suggest that landlords charged as much as three times the rent for comparable apartments in Black neighborhoods as they did in white neighborhoods. And because their renters had few alternatives, landlords were able to save money by skimping on maintenance. The result was overcrowded, rat-infested, firetrap apartment buildings—the very sorts of buildings and conditions that the propertied would later turn around and use to justify tearing down the neighborhoods and removing their inhabitants (while blaming them for the poor conditions) when they thought they could make more money as real estate “developers” than as slumlords.6

The basic condition of Black St. Louis in the 1930s (as in the decades before and the decades after) was poverty, segregation, and exploitation. And yet, as Gregory remembered in a chapter of his autobiography entitled “Not Poor, Just Broke,” these embattled neighborhoods were sites of human flourishing as well as suffering, spaces of joy as well as rage, and places where radical ideas and unaccustomed alliances took root in the 1930s, a decade in which St. Louis came as close as any other city in the nation to fulfilling the promise of the 1877 General Strike. It would take an enormous, sustained, and ongoing effort—a second counterrevolution of property, as destructive in its own way as the violence in East St. Louis—to destroy that radical possibility.

“It’s a sad and beautiful feeling to walk home slow on Christmas Eve after you’ve been out hustling all day,” Gregory’s book begins. Then he takes readers on a soft-focused tour of the hard-life side of the Ville—the emblematic Black neighborhood on the city’s Northside—in the late 1930s: ending a day’s work shining shoes in the white taverns to buy a few presents (and steal a few more than that) in the five-and-dime; stopping by his best friend’s house to drop off a ballpoint pen and look at the decorations on the tree; and waving to the neighbors and Mr. Ben, the Jewish corner grocer, whose credit would backstop the family through especially lean times, and even waving to Grimes, “the mean cop” standing out on the corner. “And then you hit North Taylor, your street… and for the first time the cracked orange door says ‘come on in, little man, you’re home now’… and you hug your Momma, her face hot from the stove.”7

Gregory’s autobiography is often excerpted to serve as an example of classism, colorism, and cruelty in the lives of poor Black children in the United States. Among the most common, most exalted, words in the book is “clean.” Child of the Depression and a segregated cold-water tenement on the Northside, Gregory longed to be clean. Years later, he remembered the “clean little girl” who would wave at him when he finished his paper route in the morning, and his fantasy that one day his father would return home, “big and clean.” He remembered the “goodness” and “cleanness” of his first love—he washed his socks and his shirts before school in hopes of impressing her—and he joined the school track team just so he could take a shower at school. He also remembered hunger and cold: breaking the window of Mr. Ben’s store to steal food; eating paste at the back of the class just to taste salt on his tongue; doing his homework with a flashlight under the covers in a freezing bedroom, only to wake up and find that one of his younger brothers had peed in the bed and his work was too sodden and smudged—too shameful—to turn in at school. Better to fail.8

Even so, Gregory describes a neighborhood that was rich in decency and generous in support, a place where Black people, in the words of the historian Earl Lewis, “turned segregation into congregation.” There was the family of a friend who fed him for a week, until the day he made the mistake of taking their generosity for granted by casually asking what time dinner would be served; the grocer who made sure Gregory’s family had food even when they had no credit left and gave them all the perishables in the store before he closed up for the high holy days; his friend Boo, who played hockey with him in the street, with broom handles and bottle caps, and went with him in the summer to Forest Park to watch the outdoor performances (and gape at the rich white people); the counselors at Camp Rivercliff, the first Black people he remembered meeting who were high school graduates; the teacher at Cote Brilliant Grammar School who appointed him to be a crossing guard; the coach at Sumner High School who invited him to join the team after seeing him lurking outside the fence; and the high school kids who cheered him as he ran the mile and won the state championship, high-stepping down the backstretch of the last lap, wearing his signature argyle socks and bandana and saluting the flag. All these people were there in the Ville, along with the hunger and the cold.9

And above all, there was his mother, Lucille Gregory, who worked all day every day to keep him in food and clothes, bought him the wallet he wanted, called home every day from the white people’s house to tell him how to cook dinner, and taught him that they were “not poor, just broke.” Who got the landlord to let them move their furniture back in from the “streetcar zone” at the edge of the street and the electric man to turn the lights back on for Christmas, and who got the haughty light-skinned doctor to give them medicine. Who was the worst cook in the world (“whoever heard of burning Kool Aid?” was a Gregory standard in later years) yet stood by him and fed him and fought for him and loved him through all the years he told her not to come to his track meets and band performances because he was “ashamed when I saw her come in wearing that shabby old coat, her swollen ankles running over the edges of those dyed shoes that the rich white folks gave her, a little too much lipstick.” Who sat on the bed with his head on her lap the night before he was to give a speech to his graduating class at Sumner, when he did not know what he would say. Who sat there and listened to him read the speech a sympathetic teacher had passed to him on his way into the auditorium, with tears in her eyes. “And she was moving her lips and I knew just what she looked like when she was alone and saying ‘Thank God, oh, Thank God,’” Gregory remembered.10

Black St. Louis in the years of the Great Migration was home to some of the greatest artists, athletes, and entertainers of the twentieth century; they were the children of migrants who had left behind the sharecropping fields of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas for hardscrabble but hopeful lives working in brick kilns, packinghouses, flour mills, and domestic service in St. Louis. Maya Angelou spent some of her childhood on the Southside, where she lived in a kitchenette much like Gregory’s on the Northside and attended Toussaint L’Ouverture Elementary School. Sent north from Arkansas by her grandmother to live with her mother, Angelou famously described St. Louis upon her arrival as “a new kind of hot, and a new kind of dirty,” a city “with all the finesse of a Gold-Rush town.” It was on the Southside that the eight- or nine-year-old Angelou was raped by her mother’s boyfriend, an incident at the center of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. And it was on the Southside that her St. Louis cousins dispensed the rough, community-based justice that many remember as characteristic of Black St. Louis at the time: they beat the rapist to death on the eve of the one-year prison term he’d been given by the state of Missouri.11

The neighborhoods remembered by Gregory and Angelou were also home to Josephine Baker, who lived in Mill Creek Valley and started out singing and dancing while her friends made music with clotheslines strung between barrels and combs covered with paper. Later, she sang on the street in front of the Booker T. Washington Theater in Chestnut Valley, until they invited her inside to join the chorus line when she was thirteen years old. The city was also home to Chuck Berry, a graduate of Sumner High School and the Poro Cosmetology College; to Ike and Tina Turner, who got their start in St. Louis clubs a generation later, at the same time that Miles Davis was starting out across the Mississippi in East St. Louis; to Robert McFerrin, who graduated from Sumner High School and would become the first African American man ever to sing at the Metropolitan Opera; and a few years later, to the poet Quincy Troupe, who started out at Vashon on the Southside before graduating from Beaumont High School, next to Fairgrounds Park. In the same way, the baseball Hall of Famer James “Cool Papa” Bell, who moved to St. Louis from Mississippi in the 1920s, was followed by Elston Howard, the first Black ever to play for the New York Yankees, after starring at Vashon High School. Similarly, Henry Armstrong, a Mississippi migrant and Vashon graduate who was the first boxer ever to hold three world championship titles at the same time, was succeeded by Archie Moore, the light heavyweight champion and another Mississippi migrant, and then by Sonny Liston, the heavyweight champion of the world, who lived as a teenager in Compton Hill. And Redd Foxx and Robert Guillaume, who would later represent the two caricatured poles of the class hierarchies of the Ville—the one as the uncouth junkman Fred Sanford (Sanford and Son), the other as a fastidious African American butler-turned-lieutenant governor (Benson)—grew up just a few years and a few blocks apart on the Northside.12

It was in these years, too, that St. Louis led the way in the national struggle for civil rights. In 1936, Lloyd Gaines sued the University of Missouri for denying his application to law school because he was Black, a case that was tried as Gaines v. Canada (Sy Canada being the name of the registrar at the university’s law school). Gaines, who had been born in Mississippi in 1912 and migrated with his mother to St. Louis as a child, was the valedictorian at Vashon. He graduated from Lincoln University in Jefferson City, the state of Missouri’s Black university, founded as a freedom school by Black soldiers at Benton Barracks. The case was tried in Columbia, the site of the all-white University of Missouri, and when the verdict went against him, Gaines appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court. Again, Gaines was unsuccessful, the court ruling that the state of Missouri’s existing practice of providing tuition for Blacks to attend out-of-state professional schools was sufficient to meet the “separate but equal” standard upheld by the US Supreme Court in Plessey v. Ferguson (1896). Gaines appealed to the Supreme Court, where his case was heard in November 1938.13

In its decision, the Court ruled for Gaines, holding that the state of Missouri was legally bound to provide Blacks with an education that was functionally as well as formally equivalent to the education provided to white students, and it remanded the case to the Missouri Supreme Court. As a stopgap, the state set up a separate law school for Blacks, Lincoln Law School, on the erstwhile premises of the Poro Cosmetology College on the city’s Northside. While awaiting the state rehearing of the case, Lloyd Gaines, after stepping out on the night of March 19, 1939, to “buy stamps,” disappeared under suspicious circumstances. He was never seen again. But the standard articulated by the court in Gaines v. Canada (1938)—that the formal “equality” represented by supplying the tuition dollars necessary to send well-educated Blacks out of the state for further education was not actually equitable—would finally be fulfilled with the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education fifteen years later.14

It was no accident that Gaines v. Canada originated in St. Louis, the city in Jim Crow’s borderlands where the train cars were switched from segregated to integrated on the way north and from integrated to segregated on the way south. “A northern city with a southern exposure,” Margaret Bush Wilson, the African American activist (and graduate of Sumner High School), termed it. St. Louis Blacks had the right to vote and strong ward-based political machines (Maya Angelou’s grandmother was a ward boss on the Southside, and powerful enough that white policemen stopped by the house to pay tribute), but segregated public accommodations—lunch counters, theaters, playgrounds, and schools. St. Louis was thus situated to produce tension over civil rights, being home to a Black middle class—educated at the city’s nationally famous Black high schools and beyond—that was accomplished, ambitious, and frustrated enough to produce and support litigants like Lloyd Gaines at the upper end of the struggle for social inclusion.15

The condition of the city’s Black neighborhoods was the primary focus of the interracial and middle-class St. Louis Urban League during the 1930s and 1940s. Every year, the league’s annual report began with a summary of its fight against restrictive covenants and the effect of segregation and crowding on Black St. Louis. “At the end of 1944, there was hardly to be found a single vacant house or flat anywhere available to a Negro family. Neighborhood covenants among whites practically encircle the entire Negro areas and have the effect of ghetto walls,” opened the organization’s report for that year. The Urban League framed its argument to the white leaders of the city in the language of humanitarian relief organizations, focusing on the deplorable conditions of human life east of Grand: “the greatest proportion of obsolete houses in the city, infested with termites, crime, delinquency, and tuberculosis.” In the real estate market, however, where the league’s hopes for integration were opposed by the realtors and the rentier slumlords and hundreds upon hundreds of racially restrictive covenants, its organizational emphasis on fostering “substantial gains in friendliness to the Negroes among an ever-widening-circle of white people” was a nonstarter. Just as maintaining a dual labor market that pitted white and Black workers against one another was the principle of industrial labor management, housing segregation was an elementary aspect of real estate: the racial border at Grand was a frontier of racial capitalist accumulation. It was unlikely to give way to increased interracial benevolence alone.16

In 1945, J. D. Shelley, who had migrated to the city from Mississippi in 1930, purchased a house at 4600 Labadie that lay in a racially covenanted neighborhood well to the west of Grand. Labadie Avenue was named for a wealthy Black grocer from the nineteenth century; nevertheless, one of Shelley’s white neighbors filed suit to void the purchase, based on a restrictive covenant signed when the house had last been sold in 1911. In 1948, the case came before the US Supreme Court, where it was heard by a panel of six justices, the other three having recused themselves because they lived in covenanted neighborhoods around Washington, DC. While holding that there was nothing inherently illegal about private agreements limiting the terms of association or membership—in the local private school or country club, for example—the Court ruled that racially discriminatory agreements were not legally enforceable. The members of a private club could do whatever they wanted, but they could not rely on the police power of the state to protect their right to do so. Having felled one of the principal legal supports of residential segregation, the Shelleys were able to move into the house on Labadie. But covenants like the one they faced down in court in the 1940s remain in many city deeds today; though legally unenforceable, they nevertheless continue to threaten, humiliate, and intimidate Black home-buyers at their long-anticipated closings.17

As well as access to better and cheaper housing, the Urban League and the NAACP sought legal access to the city’s whites-only playgrounds and swimming pools; Dick Gregory’s nostalgic memories of playing hockey in the street were shaped by the fact that Black children were not allowed to play anywhere other than the street. In 1946, the Ku Klux Klan burned a ten-foot cross in the middle of the Buder Playground in St. Louis County after Black children began to play in the park. After decades of complaints by Black citizens and their elected representatives, the St. Louis Parks Department finally relented and opened the outdoor pool at Fairgrounds Park to Black patrons. It had been the largest open-air swimming pool in the world since 1915. On June 21, 1949, the city of St. Louis announced that Fairgrounds Park would be open that summer as an integrated pool.

Having heard on the radio that the pool would be open, dozens of Black children joined hundreds of whites in the line at the gate awaiting the opening. They were admitted, but as they played in the pool, a white mob gathered outside. By the time the afternoon session ended at three o’clock, there were hundreds of angry white men, women, and children waiting at the gate. The pool attendants shut the Black children in the locker room and, after searching their lockers for weapons, called for the police to escort them out of the park. Officers from the St. Louis Police Department arrived and did just that, but no more: they escorted the Black children through the howling mob—some of the angry whites were throwing bricks and rocks—to Natural Bridge Road at the edge of the park and then told them, in effect, “Run, you’re on your own.” Robert Gammon, one of the Black children who swam in the pool that day, later remembered running as fast as he could toward St. Louis Avenue at the heart of the Ville and passing a white woman who broke stride while walking with a baby in a carriage to spit at him as he passed.18

Over the course of the afternoon and into the evening, as many as five thousand violent and enraged whites flooded into the neighborhood around the park, and roving bands armed with clubs and knives attacked any African Americans they found out on the street. “Want to know how to control these n—s?” Time magazine reported one of the marauding whites yelling at the crowd. “Smash their heads, the dirty, filthy fuckers.” It took four hundred policemen twelve hours to restore order. By the time they did, fifteen Blacks had been seriously wounded, at least two of them stabbed. The following day the mayor closed the Fairgrounds Pool for the summer.19

The anaphylactic reaction to Black children wanting to swim in the summertime suggests that racial capitalism is something more than the mobilization of race prejudice to make money, as one might conclude after a study restricted to the labor market, or to the sporadic violence and protests that had attended the recent arrival of African Americans in the College Hill neighborhood north and east of the park. The violence in Fairgrounds Park was well in excess of any economic calculation, no matter how cynical. It was a libidinal rage: psychic disgust externalized into the collective fury of race hatred. Racism and capitalism in the 1940s were inextricable. But racism and capitalism were not identical: one could not be reduced to the other. They were always in excess of one another—capitalism mobilizing and exploiting whites as well as Blacks, and white supremacy providing pleasure, even the filthy pleasures of racial disgust and collective violence, as well as profit. The Fairgrounds Park pool was reopened in 1951 as an integrated facility under federal court order (a ruling that, along with Gaines v. Canada, was eventually used as a precedent in the Brown decision), but it was boycotted by whites. In 1956, the parks department, apparently unable to imagine a pool that served only Blacks, closed down the Fairgrounds Park pool and filled it with concrete, as if the once-hallowed facility—“the largest open-air swimming pool in the world”—were a landfill or a toxic waste site.20

In St. Louis, as elsewhere, the legal struggle against Jim Crow tapped into a deeper and more radical history of grassroots organizing and direct action led by Black workers, especially Black women, and by communists. As in the nineteenth century, the working class in St. Louis was hit hard by economic depression. Industrial production in the city fell by almost 60 percent between 1929 and 1933, and unemployment increased from about 9 percent to 30 percent in the same period; 70 percent of Blacks were either unemployed or severely underemployed. During these years, a radical and powerful working-class movement emerged in Black St. Louis, threatening both the hegemony of the middle-class Black civil rights organizations, like the Urban League and the NAACP, and the racial and economic order of the city itself. For a time, working-class Black people in St. Louis, especially working-class Black women, managed to revive the revolutionary alliance of red and Black radicalism that had first been formed during Franz Sigel’s 1861 march across Missouri and the St. Louis Commune in 1877.21

Following on from the history of the communists of the 1860s and the working-class German clubs of the Turnverein of the 1890s, St. Louis at the time of the First World War was a hub of anti-imperialist communism and anarchism. Both The Communist and The Anarchist, which circulated nationally, had been published in the city since the nineteenth century, and a noteworthy leftist literary circle gathered around William Marion Reedy, the editor of the literary journal The Mirror and the author of a history of the 1877 General Strike, and Alice Martin and Harry Turner, editors of the political and cultural journal Much Ado. Martin and Turner were friends of the anarchist Emma Goldman, who stayed with Alice Martin when she was in St. Louis. The literary and bohemian scene in St. Louis shaded imperceptibly into radical politics. In addition to Goldman’s frequent visits to the city, chronicled in Living My Life, the city was home to Kate Richards O’Hare, the Socialist Party candidate for governor of Missouri in 1916 and chair of the Socialist Party’s Committee on War and Militarism. In 1917, O’Hare was convicted under the Espionage Act for speaking out against the draft and imprisoned at the Missouri State Penitentiary, where she served time with Goldman, who was imprisoned for the same offense in 1919.

Kate O’Hare’s husband Frank was the founding editor of the National Rip-saw (later Social Revolution), published in St. Louis, which served as an intellectual clearinghouse for the Socialist Party in the United States. St. Louis was also home to Roger Baldwin, who began his career together with Emma Goldman in organizing resistance to the 1917 Selective Service Act during the First World War. Baldwin went on from the struggle against militarism and the draft to join the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and then became the founding director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The city was also home to the Globetrotter Publishing House, which, in the years before the First World War, reliably turned out radical pamphlets on topics ranging from “Women under Capitalism,” “Socialism for the Farmer,” and “Socialism and Faith in Practice” to “Hands Up,” “Sabotage,” and “Militant Socialism.”22

Reedy, Martin, and Turner were followed in the next generation by Jay and Fran Landesman, who founded the St. Louis–based literary journal Neurotica (later credited as inspiration for the Beat poets of the 1950s) and ran a nightclub called Little Bohemia on the riverfront, where avant-garde artists and radicals met, sat, smoked, and schemed in the 1930s. Svavo Radulovich partnered with the Landesmans in Little Bohemia, and then later in Gaslight Square, as the scene moved farther uptown in the 1940s and after. “I found Bohemia on the Banks of the Mississippi,” wrote Jack Conroy, himself a denizen of the riverfront dive bars, who is often credited as the progenitor of the “proletarian novel.”23

It was out of this world that the most prominent St. Louis communist of the twentieth century, William Sentner, emerged. Sentner was born in 1907, the son of a Russian Jewish needleworker, and he grew up in and around the labor movement. He later joked that the first money he ever made was as a child paid to throw rocks at the windows of a factory where the workers were on strike. After two years at Washington University, where he studied architecture, Sentner dropped out to ride the rails, traveling west and eventually to Europe and the Middle East. Along the way he became a Marxist; when he returned to St. Louis, he joined Jack Conroy in the city’s John Reed Club. Named for the American journalist, communist, and chronicler of the Bolshevik Revolution, the club was a cultural spin-off of the Communist Party’s New Masses magazine and designed to channel the talent and energy of artists and writers toward revolution.

Sentner’s organizing took him to the immigrant neighborhoods around Carr Square and the Wellston Loop, the bohemian dive bars along the riverfront, and then back again to party headquarters on North Garrison—“a long dingy room, bare save for a table and a scarred piano at the far end, a book case and a table piled high with pamphlets and magazines on one side,” as Conroy described it in his novel A World to Win. During the Depression, Sentner organized—often through the Communist Party’s Unemployed Council—among the unhoused and the hungry, who were living in Hoovervilles scattered throughout the city: on the riverfront, at several spots stretching from the area north of downtown to the base of the Free Bridge south of downtown, near Hyde Park on the Northside, and near the Busch Brewery on the Southside. Taken together, these shantytowns added up to what was arguably the largest encampment of the unhoused and the unemployed in the Depression-era United States. Residents lived in small houses built of driftwood and repurposed building materials. There were as many as 250 makeshift dwellings along the riverfront in the early thirties, and at least twice that many scattered elsewhere in the city. The communities were self-governing—contentiously so when it came to food distribution and the role of Christian aid organizations in a settlement’s internal politics—and, by and large, self-policed.24

Sentner also organized in Black St. Louis, where, he later joked, he got stopped by the police every time he crossed Grand. The Black population of St. Louis had grown by over 50 percent, to around sixty-five thousand, in the years between 1910 and 1920—still less than 10 percent of the city’s population, but the eighth-largest Black population of any city in the United States. Many of the Black migrants, most of them from Mississippi, settled in Mill Creek Valley, which stretched westward from Chestnut Valley along the corridor occupied today by Interstate 64. Another group, including many of those who had fled East St. Louis in 1917, settled west of the city, in Kinloch, which was the state of Missouri’s first Black municipality. Much of the development around today’s Lambert–St. Louis International Airport is built on the ruins of historic Kinloch. Middle-class Blacks, along with many of the working poor and the just plain poor, lived in the Ville, north of downtown, where many of the city’s longest-standing African American institutions were located—the Poro Cosmetology College, with its historical ties to Madame C. J. Walker; Sumner High School, which had a national reputation for Black excellence in the 1930s; and Stowe Teachers College and Lincoln Law School, two segregated branches of the University of Missouri system.25

In November 1930, activists from eighteen states, including the organizer and theorist Harry Haywood, met at the United Brothers of Friendship Hall in Mill Creek Valley to found the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, a successor organization to the American Negro Labor Congress. They were women and men, Black and white, communists who sought to join the struggle for racial and economic justice in the United States to the global struggle against capitalism and colonialism. The protest march signs they had printed for the occasion suggested the breadth of their vision: SUPPORT THE COLONIAL MASSES; EQUAL PAY FOR EQUAL WORK, REGARDLESS OF RACE OR NATIONALITY; DOWN WITH LYNCHING, DEMAND DEATH FOR LYNCHERS; CONFISCATION OF THE LAND FOR THE POOR BLACK NEGRO FARMERS IN THE FARMERS BELT; LONG LIVE NEGRO AND WHITE WORKERS. The league lasted through the early years of the Depression and was for a time led by the poet Langston Hughes. Even after its demise in 1934, the spirit that had brought the organizers together in St. Louis in the first place, the spirit of 1877, lived on in the city.26

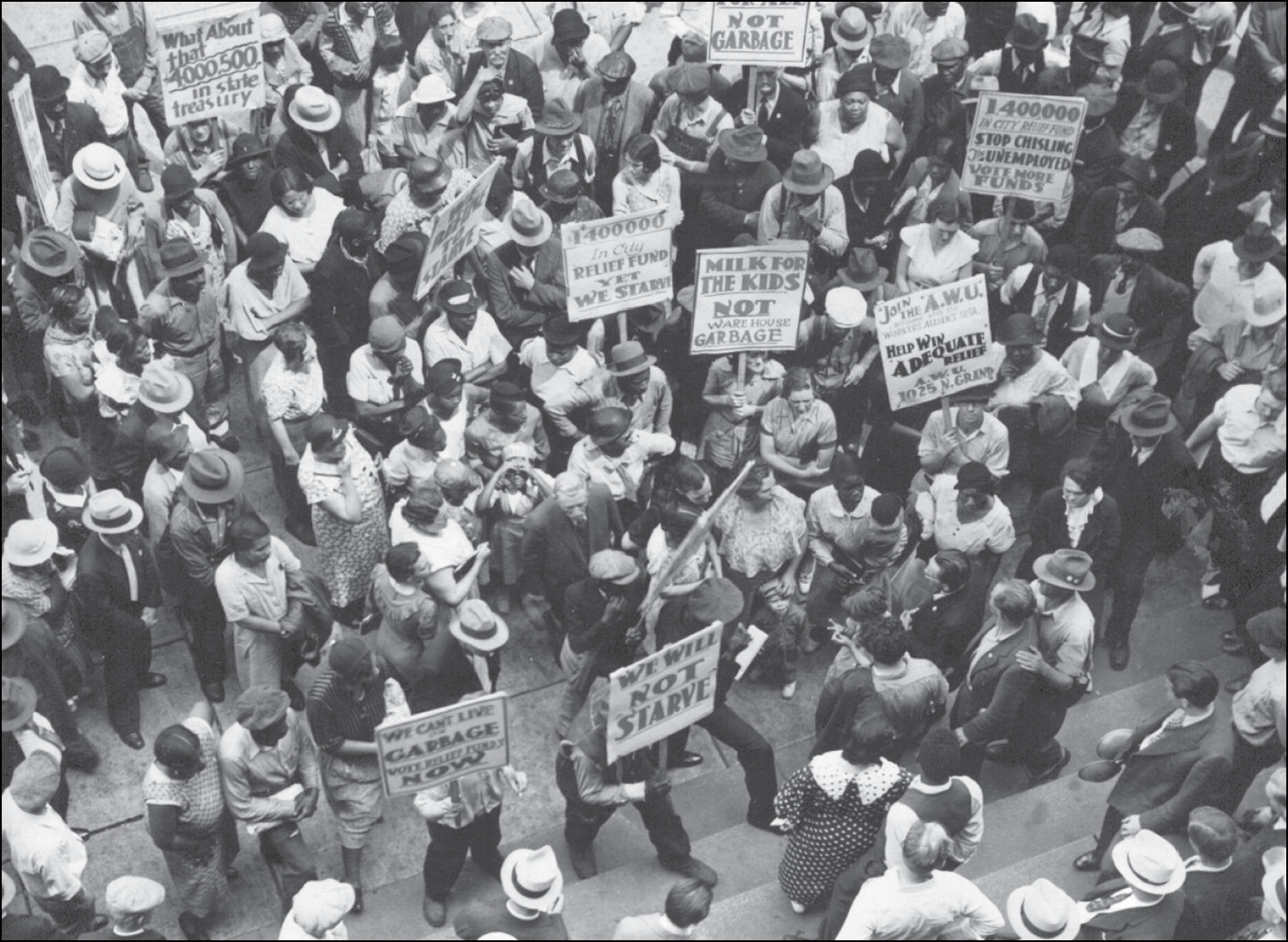

On the morning of July 8, 1932, the disinherited of the city marched on city hall, demanding to be fed. More than a thousand were gathered in front of city hall, and many were African American, among them recent migrants from the South, veterans of the massacre in East St. Louis, and descendants of the revolutionary generation that had gathered at Benton Barracks during the Civil War. There were just as many whites—men, women, and children, communists, and unemployed workers. They carried signs with slogans like NO EVICTIONS OF UNEMPLOYED and WE WILL WORK BUT WE WON’T STARVE. A group of children carried a sign demanding FREE MILK FOR THE CHILDREN OF THE UNEMPLOYED. They had marched in groups from all over the city—from the Southside, the Northside, and the central corridor—singing “Solidarity” to the tune of “John Brown’s Body.” “The burden of the song,” an observer relayed, “was that ‘We’re for inter-racial solidarity; we would rather fight than starve in slavery,’” with the refrain “Solidarity forever, our Union makes us strong.”27

Twenty-five policemen barred the entrance to city hall, where the mayor was said to be meeting with business leaders to discuss the plight of the city’s poor, and another twenty-five armed with “riot guns” and “tear gas bombs” stood ready in reserve at police headquarters, two blocks away. George Benz, an unemployed electrician and communist, stood on the steps of city hall and asked people in the crowd if they were willing to “fight” rather than “starve,” in what the Post-Dispatch termed an “inflammatory” tone. “We will, we will!” they cried. A “young Negro, apparently well-known to his listeners,” urged them on. “There is only one way left for the working class—that’s the militant way. I am speaking for the Negro workers who know how to fight and will fight. We will not continue to starve peacefully.”28

And they did not. Assembled under the auspices of the Unemployed Council of the Communist Party, a dozen of the demonstrators occupied the mayor’s office on the morning of July 11, while a crowd of three thousand gathered outside. When word reached the crowd that the mayor had refused to meet with their delegates or address their demands, one of the CP organizers climbed the steps of the Market Street entrance and urged the crowd to enter city hall. They were led by Black women, about fifty of whom started up the stairs. As they pushed forward, the organizer called for the military veterans in the crowd to follow them in support, and over a hundred did so.29

As the crowd surged upward, one of the policemen stationed near the door threw a tear gas bomb into their midst. One of the demonstrators picked it up and threw it back, and the police themselves retreated into the rotunda of the building, blinded by the gas. Moments later, however, they regrouped and charged out of city hall, guns drawn, to disperse the crowd. More police arrived, some pushing their way out of city hall, some arriving in reserve from police headquarters. They began to drive the protesters back toward downtown, swinging billy clubs, throwing tear gas bombs, and shooting into the crowd.30

Within fifteen minutes, the crowd had been dispersed. Several policemen, the papers reported, were injured by bricks thrown from the retreating throng; one was treated for a sprained wrist sustained while swinging a club at a protester. Dozens of the demonstrators, many of them children, were trampled as the crowd retreated before the tear gas and charging policemen. Four men in the crowd, three white and one Black, lay bleeding in the street, shot by the police.31

In addition to the demonstrators inside City Hall, who were arrested, several dozen others were arrested in the immediate aftermath of what soon came to be known as the “July Riot.”32 A photograph of a court hearing on July 14 reveals that the “communists” accused of disturbing the peace were Black and white, men and women. On the same day the court issued warrants for eleven men and one woman, including all four of those who had been shot by the police, on the more serious charge of rioting, punishable by up to a year in the Workhouse (the name for the St. Louis City Prison down to this day) and a $1,000 fine. On the afternoon of the protest, the city’s police commissioner, declaring himself in “sympathy” with the unemployed but intolerant of any further demonstrations, had instructed the force to break up any subsequent meetings of the Communist Party in St. Louis. In the following days, uniformed and armed policemen arrested suspected party members at a meeting of the Unemployed Council near Union Station and at party headquarters on North Garrison.33

The account of the violence that emerged on the left was of a peaceful march of the hungry and the unemployed that had been interrupted by a police riot. Speaking at a meeting of the Liberal Club, one of the organizers (who refused to give her name out of fear of police retaliation) described the demonstration in front of city hall as one in an ongoing series of “hunger marches” in the city. “People would just get up and state simply that they had nothing to eat,” she recounted. “Women would get up and say, ‘We can’t go home because we have nothing to give our children and we just can’t face them.’” If there were communists among them, that was nothing to be ashamed about, she argued: “Even a Communist can be hungry.” If some among the crowd fought back when attacked by the police “with tear gas, clubbing, beating, trampling women and children,” they could not really be blamed. “These people were not to be fooled with. They were hungry. They had nothing to eat and no money.” Many of those who were arrested, the woman continued, had been beaten while in police custody. The police had instigated the violence by attacking a peaceful protest, beaten prisoners in custody, and then turned around and charged the hungry and the innocent with “disturbing the peace.”34

The unemployed marches of the 1930s brought together Black and white working people, women and men. Out of them grew the strike at Funsten Nut, led by Black women. (St. Louis Post-Dispatch/Polaris)

Whatever they thought of communists, Blacks, or the unemployed, the members of the board of aldermen recognized that as long as people were hungry, further disturbances were likely. By the end of the week of the food riot, the board passed an emergency motion to appropriate $25,000 to set up food distribution centers throughout the city. In their assembly, the demonstrators at city hall had forced the government to account for them and their families. By the end of the summer, most of those charged in the aftermath of the violence were acquitted or sent home by hung juries.35

The following summer, a group of African American women employed as nutpickers went out on strike at R. E. Funsten Company, which had several processing facilities in St. Louis. The organizers included some of the veterans of the previous summer’s action at city hall, including an African American woman identified in the relatively sparse archival record of the strike as “Mrs. Wallace,” who had been among those arrested in the mayor’s office. By the end of the summer, she and the others had led one of the largest strikes of Black women in the history of the United States.36

The vast majority of working-class Black women in St. Louis were employed in domestic service—cooking and cleaning in the homes of wealthy and middle-class whites who lived in the city’s West End and emerging suburbs. These women, like Lucille Gregory, worked for wages barely sufficient to keep a roof over their own family’s head, and often insufficient to keep their children fed. There were also many Black women who worked in food processing in St. Louis—and 2,500 of them worked at Funsten Nut, the largest single employer of Black women in the city.37

The production lines inside the sixteen Funsten plants scattered across the St. Louis metro area were segregated. Black women shelled the nuts, separating the meat from the hull, and a much smaller number of white women, many of them immigrants from Poland, sorted the nuts into halves and pieces. Because they were sorting nuts downstream on the line from the pickers, the white women in the plants were allowed to come into work fifteen minutes later than the Black women, and they were allowed to go home fifteen minutes earlier. The pickers worked twenty-five pounds at a time, and after each stage both hulls and meat were weighed to ensure that no nuts had been stolen. While the whites who worked in the plant were paid a weekly wage of around $3, the Black pickers were paid by the pound—three cents a pound for halves and two cents for pieces. Many complained that they were paid for totals smaller than what they had recorded during the day, but even under the best circumstances, it was very unusual for a picker at Funsten to make $2 in a week. They worked in poorly lit, unventilated basements where the air was so dusty that the workers at one plant kept the doors open through the winter. Their hands were cracked and cut by the work, and many developed chronic respiratory conditions similar to those suffered by men working in coal mines.38

On May 15, 1933, about five hundred Black women walked off their jobs at Funsten Nut, demanding that the company pay them a “living wage.” The women had begun to organize in a series of secret meetings convened by the communist labor activist William Sentner and held over the course of the spring; first six, then twenty, and then fifty women were involved. On May 13, several women who had joined the Food Workers Industrial Union convened a meeting of seven hundred workers from various Funsten plants. They voted to go on strike if they did not receive an immediate raise. The first group to walk out on the fifteenth set out from the Delmar plant and marched to other plants located all over the city, urging the women inside to join them. Many did, although few of the white women on the production lines joined the Black women outside on the first day. One white worker, Nora Diamond, was quoted in the labor press as saying that she stayed on the job because the wages and working conditions of the Black workers “don’t affect me… and because [the strike] was led by the wrong kind of people, Russians, foreigners,” which was to say, communists. In spite of these time-honored, and self-defeating, prejudices against Black and red, many of the white women joined the picket lines on the second day of the strike, and the Funsten plants throughout the city were completely shut down.39

The scene outside the plants during the nine days of the strike was by turns (and depending on one’s perspective) inspiring, chaotic, and violent. The women carried signs reading ANIMALS IN THE ZOO ARE FED WHILE WE STARVE, and FIGHT FOR THE FREEDOM OF LABOR—DEMAND UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE. Many carried their Bibles with them, and they periodically interrupted the picketing to stop and pray. Some of the striking women were joined on the picket lines by their husbands and children as they marched from plant to plant calling for the women inside to come out. The city police were soon deployed to the plants to escort strikebreakers through angry crowds of strikers. Over the course of the strike, the police arrested at least ninety strikers (including Sentner) on charges of disturbing the peace. Some of the arrested strikers made their initial court appearances still bruised and bandaged from the curbside justice to which the arresting officers had subjected them.40

At the head of the crowd outside the closed plants was a Black woman named Carrie Smith, an eighteen-year veteran of Funsten, who had urged a strike vote at the meeting on May 13 with a Bible in one hand and a brick in the other; Smith was subsequently appointed chair of the strike committee. The strikers wanted to be paid, she said, “on the basis of ten cents a pound for half nuts and four cents a pound for pieces,” or about $6 a week. “We believe we are entitled to live as well as other folks live, and should be entitled to a wage that will provide us with ample food and clothing,” she told the mayor at a meeting called to mediate the strike. At the same meeting, Ardenta Bryant told the mayor that the money she earned at Funsten was not enough to feed her family and she was consequently forced to rely on public assistance to make ends meet, thus driving home the strikers’ point that Funsten was taking a subsidy from the city: it was taxpayers who paid for the public assistance that as many as two-thirds of the nutpickers required to keep food on the table. Outside the meeting, 450 Black women protested, having marched from Communist Party headquarters on North Garrison.41

On the ninth day, Funsten folded. After a meeting with the mayor and company leaders Eugene and Fairfax Funsten on May 24, Carrie Smith emerged from city hall with an offer from the company to pay the pickers ninety cents per twenty-five-pound box, which represented a doubling of their wages and came close to the “ten and four” (ten cents for halves, four cents for pieces) they had struck to obtain. Along with the mayor, she drove to Communist Party headquarters, where seven hundred strikers had assembled, and presented them with the company’s proposal for a vote. It was unanimously approved, and on May 25 the African American nutpickers and white sorters—many white workers had joined the strike on the second day, and the settlement represented a substantial raise for them as well—returned, triumphant, to work at Funsten.42

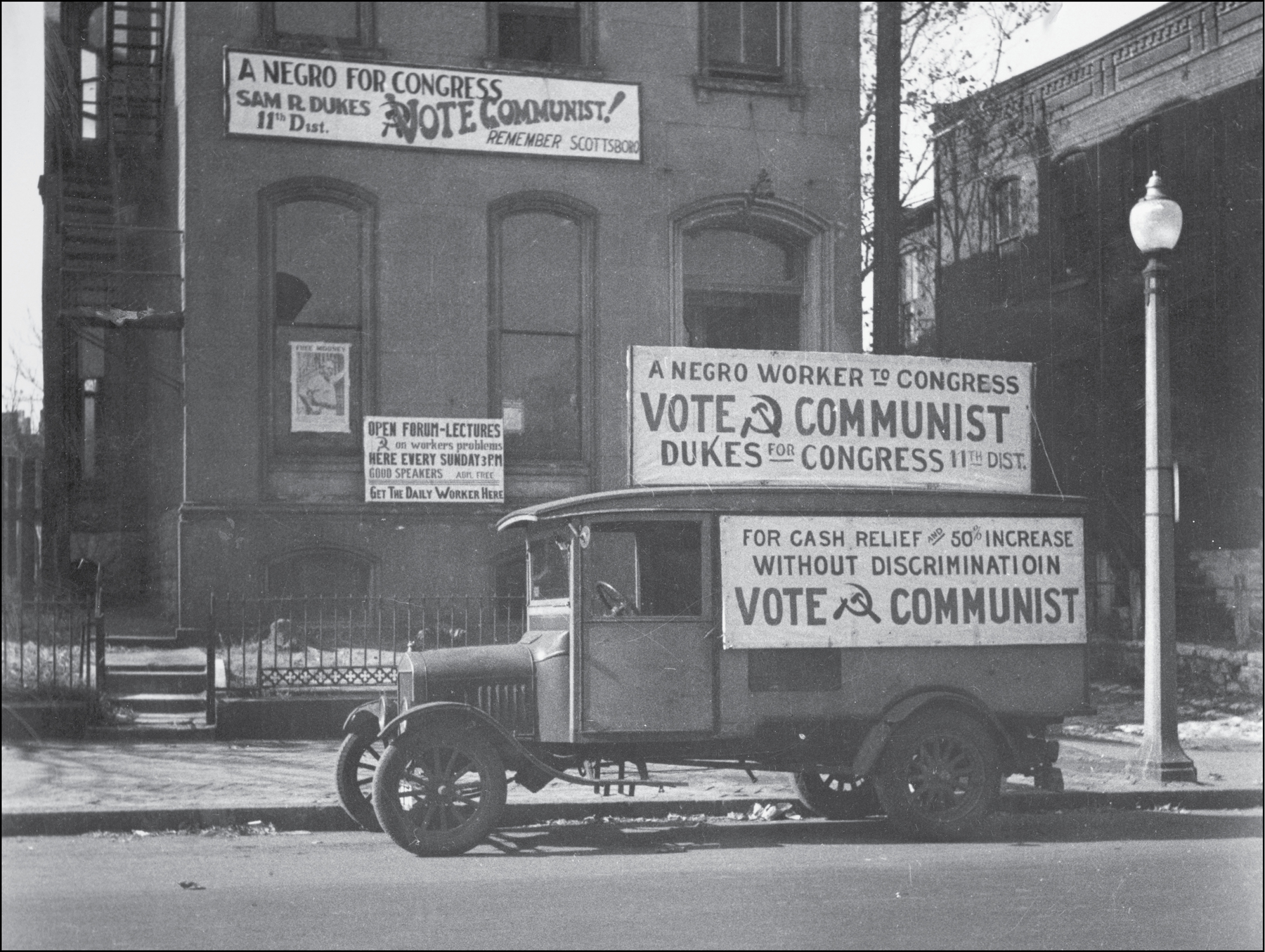

The Communist Party was active and influential in St. Louis in the 1930s, actively seeking Black members and supporting the struggle of Black workers. (State Historical Society of Missouri)

Before the strike, the nutpickers had been ignored by mainstream civil rights organizations as well as the existing trade unions. After the strike, both the civil rights organizations and the labor movement sought to capitalize on their success. The Communist Party hoped that the Funsten strike would be a watershed moment in their effort to organize Black workers nationally. “You must follow these steps of these nutpickers,” the Trade Union Unity League urged other St. Louis unionists in a pamphlet issued at the time of the strike. “You must organize yourselves and strike!” The leaders of the strike, including Carrie Smith, were held up to the nation in the party journals and at party meetings as examples for all workers. The nutpickers had provided a model “that can and should be followed in every section of the country against the slavery imposed on women,” wrote a party journalist in Working Women. The nutpickers had “aroused the masses of St. Louis like no other strike in years,” gaining the “full sympathy and solidarity of the St. Louis working class.… One would think that the Negro women had been for years trained in the working class movement.” And indeed, in the aftermath of the strike, thousands of Black women, both in the nut plants and in other industries (especially meatpacking), joined the communist-aligned Food Workers Industrial Union.43

The conceit that the nutpickers had somehow managed to act and organize according to a party script they had never actually seen papered over a fundamental problem in the communists’ approach to co-organizing with African Americans, and with African American women in particular. Both in St. Louis and elsewhere, party organizers were among the earliest and most stalwart supporters of Black workers. When Black women formed a picket line in front of Funsten, the communists walked with them; when they had to feed their families during the strike, the communists provided the food; when they went to jail for “disturbing the peace,” the communists went too. But they did so according to an account of the strike understood as an action taken first by workers, second by women, and only incidentally by African Americans. Their theory made it hard for them to understand a struggle that was rooted in the material lives of working-class Black women in Mill Creek Valley and the Ville, in the specific forms of discrimination, exploitation, and violence faced by people who were, all at once, workers, women, and Black (not to mention wives, mothers, and Christians) rather than in the more general circumstances of “the working class.” For the communists, the Bibles and prayers on the picket line were simple remnants of archaic ways of thinking, old superstitions and patterns of affiliation that would soon give way to the self-evident imperatives of working-class struggle.44

Years later, the Black communist Hershel Walker would remember the 1930s as a decade of terrific possibilities and lost opportunities for the Communist Party in St. Louis. Walker had been born in Arkansas in 1909, the son of a sharecropper. He migrated first to Memphis as a young man, and then to St. Louis in 1930, where he initially stayed with one of his brothers who had migrated several years earlier and lived on the Northside, near Carr Square. It was his brother who introduced him to the Communist Manifesto, the Unemployed Councils, and the party. Impressed that party headquarters on North Garrison was only a few blocks from where he lived, near the heart of Black St. Louis, and that the party membership (and leadership) was roughly equally divided between Blacks and whites, Walker soon joined the Communist Youth League. He would later become the city’s party chairman.45

Walker recalled the vibrancy and radicalism of politics in Black St. Louis in those years. In addition to the communists, there was the March on Washington Movement (Walker remembered it as “the Randolph Movement,” in honor of one of the principal architects, A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters), which was anticommunist but rigorously focused on economic justice. And there was what Walker called “the Japanese Movement,” the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World, which promoted the idea that Japan would lead a worldwide uprising of the darker nations of the world against imperialism and white supremacy. Mostly forgotten today, the PMEW was centered in St. Louis, where it had thousands of adherents.46

In these years, the Black Marxists C.L.R. James and Claudia Jones visited Missouri—not because they thought working-class Black people in the Midwest needed their guidance, but because they wanted to find out what working-class Black people in the Midwest were doing and learn from them. Another regular visitor to the city was William H. Patterson, leader of the Communist Party’s International Labor Defense section in the United States and future author of the charges contained in the book We Charge Genocide, which was presented to the United Nations in 1951 on behalf of Black Americans. In February 1942, Patterson gave a speech in the city entitled “Sikeston: Hitlerite Crime against America,” which condemned the lynching of the mill worker Cleo Wright and white mob violence in southeastern Missouri in January of that year. The historian Herbert Aptheker, the infamous communist intellectual and, later, the literary executor of W.E.B. Du Bois’s estate, was also a frequent visitor to St. Louis during these years. Many years later, Hershel Walker cited the influence of Aptheker’s work on his own thinking about the importance of the Black church, which he had underestimated during his days as an organizer.47

When he was later asked about the decline of interest among St. Louis Blacks in the Communist Party, Walker recognized the effect of Cold War anticommunism, but emphasized the limitations of the party itself in its relation to the people in the Black neighborhoods of St. Louis in the 1930s and ’40s. The party, he said, had been too focused on getting people to become communists and missed the opportunity to engage people who might have shared many of the party’s positions but would never become communists—specifically church people like Carrie Smith. Walker was pressed by the interviewer: “You mean, you didn’t bring them along?” No, he said, “We couldn’t bring them along. We should have left them where they were.” Not by ignoring them, he clarified, but by engaging them where they lived, in their neighborhoods, in the particularity of their own lives and beliefs.48

This is not to say that the strike had left the nutpickers’ relationship to their churches and communities unchallenged. In spite of the entreaties of many of their parishioners, the ministers in the city’s Black churches did not support the strike and focused instead on the foreignness of the communist organizers, many of whom were Jewish, and the hostility of the party to Christianity. Their resistance tested the allegiance of the strikers, who felt abandoned by Black ministers who refused to take up collections for their strike fund. “None came to our rescue but the Communist Party,” Carrie Smith later wrote. Both the Urban League and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (the pan-Africanist Garveyites) sat the strike out—the UNIA because of the enduring sectarian polemic with the communists about whether working-class Blacks were first and foremost workers or first and foremost Blacks, the Urban League because the middle-class nature of its prestrike version of racial uplift provided precious little in the way of resources for understanding a movement led by working-class women rather than educated ministers and wealthy professionals.

From the Urban League’s perspective, the communists, far from addressing the population’s true needs, had taken advantage of “hungry, destitute, and desperate people [who] would follow wherever there was a ray of hope for some kind of relief.” “We felt the Negro was being used by something [he] was not a part of and which he was not in sympathy with,” read one Urban League after-action account of the strike. The city’s middle-class civil rights “leadership” was, by and large, unable to understand the capacity of the nutpickers to organize themselves and point the way forward for everyone else, just as it was apparently unable to find language to understand a struggle that was led by Black women rather than men. Even more revealing, perhaps, was the explanation offered by a longtime Urban League organizer: “The League did not take an active part in this Strike.… The Negro women working in these storefronts… many of them had open sores on their arms and their hands—no health requirements were enforced—and for that reason the League wasn’t interested in furthering their cause.” Perhaps the most charitable reading of that remark would be, for a time, the bourgeois integrationism and uplift ideology characteristic of the Urban League in the early 1930s made it difficult for some of its members to understand, make common cause with, or, still less, believe that they had something to learn from the Black women who went on strike at Funsten.49

But learn they did. The St. Louis Urban League had been founded in 1918 to “assist” southern migrants in their transition to life in the city. From that time on, the league’s Women’s Division served as a matchmaking agency for white women seeking domestic servants and Black women seeking jobs: league members evaluated the job-seekers’ abilities, tried to place those whom they considered well mannered and tidy in jobs as cooks, maids, or laundresses in suitable white households, and steered job-seekers away from unsuitable jobs. In September 1933, however, the Women’s Division began to follow a different pathway. Responding to the complaints of Black women—who accounted for about 40 percent of the domestic service employees in the city—the Women’s Division held a mass meeting for the women to air their grievances. First among them was their exclusion from the protective provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act, which excluded the vast majority of Black workers in the United States by offering no provision for domestic servants (or landless agricultural workers, many of whom also were Black).

But many of the thousand or so African American domestic workers who attended the meeting expressed more immediate concerns about the condition of their employment. They were forced to pay for uniforms and streetcar fare. They had to be available whenever their employers wanted them and to make ends meet whenever they did not—when their employers were away on vacation, for instance. At the end of the meeting, the women of the Urban League joined the domestic workers in agreeing to a set of industry standards: a maximum of forty-eight hours of work a week for live-out domestics and fifty-four hours for those who lived in; overtime pay by the hour; one week of paid vacation per year and one day off per week; private living space and bathroom for those who lived in; accident insurance; and transparent and binding agreements about who would cover work-related expenses. Although these standards were not binding on white employers, they represented a substantial evolution in the middle-class Urban League’s attitude toward working-class Black women—from paternalistic “support” to something closer to actual solidarity.50

Black workers in St. Louis continued to strike through the years of the Depression and the Second World War. Because Blacks had long voted in St. Louis, the city’s freedom movement, from the beginning (and to the end), emphasized economic equality in addition to issues of access to public accommodations, parks, and pools. The critique of economic injustice that historians identify as having come to characterize the mainstream of the civil rights movement only in 1968, with Martin Luther King Jr.’s support of the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis, had a much longer history in St. Louis. Organizing through the March on Washington Movement, the Communist Party, and the industrial unions of the CIO (the AFL locals remained segregated), Black workers in St. Louis sought both equal access to jobs and equal treatment on the production line once they got those jobs.51

In 1937, young women from the Black neighborhoods of St. Louis formed the Colored Clerks’ Circle in order to pressure businesses that operated in Black neighborhoods to hire Black clerks. “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work,” they urged Black consumers, coining a phrase that became a national standard. The Black women of the CCC demonstrated in front of Walgreen’s, Gerken’s Hats, the Matier Shoe Store, and the Nafziger Baking Company; at Kroger’s for a month; and outside the National Clothing Store for twelve hours on a winter day when the temperature was three degrees. The result was 150 stores picketed and 200 jobs secured. The Urban League was grudgingly respectful of the young protesters who had secured these jobs for their community, but unwilling to acknowledge that the established civil rights organizations might have something to learn from the young people on the streets in front of the stores. “The one lamentable fact,” St. Louis Urban League staffers wrote in the organization’s national journal, “is that the mass-pressure method of securing jobs… does not seem to have evolved a well thought-out theory of action. Too many energetic Negro youths have gone to battle armed with no theory at all, but simply a rugged determination to get jobs.” Their worry about the young people who were challenging the merchants and changing the city was a bourgeois mirror image of the communists’ anxiety that Black women activists needed a proper theory.52

When workers at Emerson Electric, mostly white but including some Black porters and janitors, went on strike on March 9, 1937, Blacks who worked elsewhere in the city supported them. Workers at the downtown plant simply sat down on the job; by occupying the factory and shutting down the production line, they forestalled any possibility of bringing in replacement workers. The striking workers organized a three-shift security watch, played cards and checkers, staged shows, produced a daily newspaper, and held daily prayer services for the observant. They were visited by Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party candidate for president in 1936, who marched with protesters outside the plant carrying a sign reading CAN WE LIVE ON PROMISES?

William Sentner, now an organizer for the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers (CIO), was one of the leaders of the strike. He led a march on city hall and a sit-in at the St. Louis Relief Administration office to demand that the city provide food for the striking workers and their families. When the mayor temporized, Sentner’s small army of communists and trade unionists occupied city hall, just as they had done in 1932. And also as in 1932, the occupiers were both Black and white, women and men. Supported by a coalition that had its roots in the Unemployed Councils, the Communist Party, the “July Riot,” and the Funsten Nut strike, and represented by a negotiating committee that included at least one communist (Sentner), one African American (Troy Lee), and one white woman (Hilda Marasche), the workers at Emerson held the plant for fifty-three days—the second-longest sit-down strike in the history of the nation—and won a new contract that included a substantial wage increase. In the teeth of the Depression, Black and white workers in St. Louis had created a radical alliance capable of exacting substantial concessions from both business interests and the city government.53

The Second World War transformed the economy of St. Louis. Ever since the development of the nineteenth-century lead smelters and military bases that supported the expansion of the American empire to the Pacific and beyond, St. Louis had boasted a strong military-industrial sector. As the US economy converted to war production, St. Louis industrialists were at the forefront. On the eve of Pearl Harbor, there were no fewer than sixty thousand military contracts being fulfilled in St. Louis. Almost three hundred St. Louis firms were involved in wartime defense work, including the airplane manufacturer Curtiss-Wright, which was the second-largest recipient of defense contracts in the nation. By the end of the war, 75 percent of the industrial firms in the city were doing defense work—well above the national average.54

For factory owners, war production was easy money. War production contracts were generally on a cost-plus basis, with the government bearing the cost of plant conversions plus a guaranteed profit margin. In 1940, Atlas Powder became the nation’s largest producer of TNT; the American Car Company and St. Louis Car Company switched over their streetcar production lines in order to build tanks. During the war, Emerson Electric grew from a regional supplier of small motors and consumer electronics into one of the largest industrial firms in the United States. The army’s Office of Production Management built a 700,000-square-foot factory on the Emerson campus, where the company manufactured 40,000 gun turrets for the B-17 Flying Fortress bombers during the war. In the process, Emerson’s annual revenue grew almost 200 percent between 1940 and 1944. The same company that had $4.8 million in sales in 1940 made $487 million in military contracts over the course of the war. With federal support, US Cartridge built the largest small arms ammunition plant in the world near Pine Lawn, and Mallinckrodt Chemical constructed the largest high-explosives plant in the nation in nearby Weldon Springs.55

Much of the practical work of building the atomic bombs that were eventually dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was done in St. Louis. With government support, the Physics Department at Washington University built a particle accelerator to aid in the creation of weapons-grade plutonium, and scientists from Monsanto provided the plutonium for the first atomic bombs. Mallinckrodt Chemical processed sixty tons of uranium for the Manhattan Project, including the uranium that provided the raw material for the first sustained nuclear chain reaction in 1942—an aspect of the city’s role in global history that continues to unfold in underground waste dumps and toxic groundwater across the region today.56

For Blacks, who had long been shut out of industrial jobs in St. Louis, sharing in the region’s wartime economic gains required fighting for jobs. In St. Louis, that fight was led by the local office of the March on Washington Movement, one of the largest and most radical branches in the nation. After a threat from the Movement had forced President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 Executive Order 8802 outlawing racial, gender, and religious discrimination in federal defense work, the organization’s efforts focused on trying to get St. Louis companies to honor both the letter and the spirit of federal law. During the war, Black workers picketed Carter Carburetor and Bussman Manufacturing, protesting their whites-only hiring, and they also picketed US Steel and US Cartridge Company’s massive “Small Arms” plant (as it was known), the largest plant of its kind in the world. Picketers demanded jobs for Black workers in general and Black women in particular, with signs reading, TWENTY THOUSAND WORKERS AT SMALL ARMS PLANT IN PRODUCTION—NOT ONE NEGRO, and 8,000 WOMEN EMPLOYED—NOT ONE NEGRO WOMAN. Hershel Walker gave a sense of the dangers faced by African American justice-seekers in those times: for the fifty or sixty Black protesters in the “march on the bullet plant,” which employed tens of thousands of whites—rural Missouri whites who had come to St. Louis for war jobs they desperately needed—approaching that plant “was taking your life in your hands.”57

The reality of high employment and the exigency of war production placed labor in a bargaining position that had been unimaginable in the lean years of the 1930s. For the most part, however, working people were forced to accept bargains made by political and organizational leaders: communists were instructed by the Comintern to support the war effort in accordance with the “Popular Front” strategy of postponing the struggle against capitalism until after the defeat of fascism, and the national unions (including the CIO unions) signed no-strike pledges. These agreements did not stop Black workers in St. Louis from staging wildcat strikes for better pay, better working conditions—including the integration of the production line—and the right to unionize at those plants where Blacks were employed, including Wagner Electric and, eventually, Small Arms. They were supported by the local chapters of the March on Washington and by William Sentner and District 9 of the Electrical Workers (in defiance of the position of the national CIO). In the fall of 1943, six hundred Black men walked off the job at General Steel Castings to protest the fact that the plant employed no Black women. Gradually, they made progress. Nine hundred Blacks, including two hundred machinists and three hundred women, were working at Small Arms by the end of 1942; by the end of the following year, more than four times that number worked at the plant, although, in deference to the racists working elsewhere in the plant, all of them were located in a single building, number 202. Neither the shame of East St. Louis nor the successes at Funsten Nut and Emerson Electric could convince some whites that they should make common cause with their fellows on the line.58

Almost as soon as Blacks won positions on the production lines, industry leaders began to worry about the economic wind-down that would come with the end of the war, which would require billions of dollars of capital to reconvert to peacetime production. Ten million soldiers would return, and they would need work. For many war workers, especially African American and female war workers, and most particularly African American female war workers, reconversion portended a disaster.

Even before the end of the war, production cuts began to bite. As government orders declined, plants cut overtime, which cut workers’ take-home pay as much as 30 percent. Because they had been the last to be hired, African Americans were the first to be let go as military orders declined and wartime production lines were shut down. Thus were the discriminatory hiring practices of the early war years converted into unemployment and economic precarity in the years immediately following the war. In July 1943, US Cartridge cut production in building number 202, laying off an entire shift; in November, the company laid off one thousand more Black workers. The aircraft producer Curtiss-Wright laid off 50 percent of its Black workers in the same year. Carter Carburetor and McDonnell-Douglas soon followed, laying off Black workers as government orders declined. White workers were also threatened by the cutbacks and often responded with misguided aggression toward their Black coworkers. Beginning in the spring of 1944 at the General Cable Company, and lasting through the duration of the postwar reconversion, white industrial workers in St. Louis staged a series of hate strikes protesting the hiring of Black workers.59

Hate strikes were only one aspect of the social disorder that many feared would follow the inevitable postwar industrial contraction. The recent history of capitalism provided an indelible memory of what might happen if reconversion failed to provide jobs for ten million returning veterans: the hoboes and Hoovervilles of the Great Depression and, most pointedly, the 1932 Bonus Army of over forty thousand unemployed workers, many of them First World War veterans, who marched on Washington and camped in the city while demanding payment of wartime military bonuses (and who were eventually routed by the DC police and army units under the command of General Douglas MacArthur the younger). In St. Louis, Sentner and the CEO of Emerson Electric, Stuart Symington, joined a group of other local leaders—an Episcopal bishop, who sat at the head of the group, the CEO of Monsanto Chemical, and several lawyers—in what they termed the Serious Thinkers Club to work out a postwar settlement for the city. Symington and Sentner were profiled in Fortune magazine—“A Yale Man and a Communist”—as examples of what was possible (no strikes, the production of hundreds of thousands of gun turrets, the massive expansion of production and revenue) when the representatives of capital and labor trusted one another and pulled together. By the close of the war, Symington had been appointed by President Harry S. Truman to be the head of the government’s Surplus Property Board, which was responsible for the conversion of war-related government property to the use of private enterprise.60

Nationally, the solution to the economic crisis of the end of war turned out to be simply not letting the war end. The continuation of a global fight for freedom, epitomized by the Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of Europe and the beginning of the Korean War in 1950, were the most obvious material manifestations. Both required continued government investment in the defense industry. Almost as soon as it had closed down, the US Cartridge production line that produced 30mm small-arms ammunition for the army in the Second World War reopened as a plant producing 105mm artillery shells for the US Army to use in Korea.

In St. Louis, Sentner and the UE (United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers) supported plans for a massive Missouri Valley Authority—a public works program on the model of the Tennessee Valley Authority—that would transform the Missouri River into a series of flood-controlled reservoirs that could be used by valley farmers for irrigation during the planting season. In 1944, they got a guarantee of union jobs in the enormous Pick-Sloan Missouri River Basin Project (not quite as enormous as the MVA, but still enormous) begun in 1944: five huge earthen dams intended to provide flood protection and water for irrigation to the Missouri Valley’s agricultural settlers. As visionary as the scheme must have seemed to labor activists in St. Louis, it was framed by the same imperialist blinkers that had narrowed the vision of many of the nineteenth-century radicals. The Pick-Sloan dams flooded hundreds of thousands of acres of land on Lakota and Dakota reservations—Santee, Yankton, Rosebud, Lower Brule, Crow Creek, and Standing Rock—themselves vastly reduced from the size of the Great Sioux Nation established by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. It was, according to historian Nick Estes, “a twentieth-century Indigenous apocalypse”—and one that foreshadowed a similar catastrophe along Mill Creek Valley in St. Louis a decade later.61

These postwar “bargains” marked the subordination of the radical alliance of communists and African Americans that had shaped the labor history of St. Louis in a new relationship between capital and labor. These new arrangements were subsidized by the US government and made under the Taft-Hartley Act (1947), which required union leaders to sign an oath attesting that they had never been communists and had never supported the overthrow of the US government. This requirement effectively sidelined the most radical of the unions, like Sentner’s UE, which went from 600,000 active members in the years immediately after the war to 200,000 by 1953. Sentner himself was voted out of his leadership position in the UE in 1949 and convicted in 1952 under the 1940 Smith Act for having once advocated the violent overthrow of the United States—in other words, for having been a member of the Communist Party. Though his conviction was overturned in 1958, his career as an organizer was over.62