9 | “BLACK REMOVAL BY WHITE APPROVAL”

When white folks want you gone, you gone.

—JAMALA ROGERS, Ferguson Is America

THE 1907 CITY PLAN FOR ST. LOUIS WAS THE FIRST COMPREHENSIVE planning document produced by any city in the United States. It proposed a network of parks and vistas of the Mississippi River that would bind the city neighborhoods together, with a huge downtown park devoted to the city’s greatest geographic (and scenic) asset—the Mississippi River. The plan recommended channeling industrial development into certain areas of the city, thereby minimizing the effects of nuisance and pollution on the general population while enhancing “property values” throughout the city. It was to be government action taken on behalf of regulated economic development, public health, and civic cultural and (white) racial cohesion. The plan specifically mentioned the need to create connections and social harmony between various ethnic enclaves in the city—Italian, German, Russian, Jewish, “and so on.” As for Black St. Louis, it recommended the “transformation” of Chestnut Valley into a public park.1

At the heart of the plan that lies at the root of the history of city planning in the United States was an expressed horror at the Black-owned and -operated nightclubs, saloons, and bordellos in the neighborhood along Chestnut Street between city hall and Union Station. And the same document proposed a solution that has shaped the history of St. Louis (and the United States) down to the present day: take it, tear it down, and bury the memory.

No single person’s name has been as consistently associated with the destruction of the neighborhoods of Black St. Louis as Harland Bartholomew. Bartholomew, who began working for the city of St. Louis in 1916, was appointed city planning commissioner in 1919 and held that role until 1950. During that time, he was also the principal of Harland Bartholomew and Associates, which served as a consulting firm for over 150 American and Canadian cities, including Atlanta, Chicago, Honolulu, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Memphis, New Orleans, New York City, Vancouver, and Washington, DC. Bartholomew was an early advocate of comprehensive planning, single-use zoning, and automobile-based transportation planning. He was appointed to various federal commissions, frequently testified before Congress, and capped his career as chairman of the National Capital Planning Commission, to which he was appointed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He has, with some justice, been called “the father of American urban planning.”2

For Bartholomew, city planning, especially zoning, was an expansion of the “police power” of the state—the exercise of law in support of the general welfare. Along with Progressive-era city planners in New York and Chicago, Bartholomew outlined a vision in which “zoning is a justifiable use of the police power in the interests of health, safety, and the general welfare,” with “general welfare” defined as enhancing property values in order to support a city’s tax base. Although he was living in a city that had just passed a racial segregation ordinance based on the argument that Black “invaders” were destroying the property values in “white” neighborhoods, and across the river from a city in which white terrorists had driven thousands of Blacks from their homes and into St. Louis, Bartholomew alluded only indirectly to the relation of racism and segregation to zoning and real estate in the tens of thousands of pages of city plans he produced over his career. About as close as he came in his plans for the city of St. Louis were his repeated uses of the phrase “the district east of Grand” in his 1919 plan, along with his observation that most of the areas of the city that he hoped to zone as “single-family residential” already had “restriction in the deeds” that protected the value of the properties from unwanted development.3

It was Bartholomew’s particular malign genius (one historian has termed it a form of “administrative evil”) to be able to translate the terms of existing institutional racism—the “segregation ordinance” and the “restrictive covenant”—into the notionally color-blind terms of liberal white supremacy—“property values” and “the public good.” This was the role he had played as the chair of the Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership, a position he was appointed to by the floridly racist President Herbert Hoover in 1931 in recognition, according to the historian Richard Rothstein, of Bartholomew’s skill in keeping St. Louis segregated even in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s 1916 decision in Buchanan v. Warley. Zoning, Bartholomew had written in defense of his 1919 plan for the city, was protection “against the day when private restrictions expire.” Zoning, that is to say, was segregation by other means: “before decay sets in it seems absolutely necessary, logical, and reasonable to establish permanent restrictions which will continue to preserve those districts in their present condition.” Necessary, logical, and reasonable—bywords of the man who, by 1931, would be the segregation and suburbanization czar of the United States, using St. Louis, by every account, as his laboratory.4

As his reputation and power in St. Louis grew in the years after the First World War, Bartholomew turned the city’s attention to the warehouse district that had once been the administrative center of the American empire. A 1915 effort to replace the warehouses and lean-to houses that stretched along the city’s eastern edge had been defeated by a campaign centered on the message that, if “15,000 Negroes who now live in that district will be forced to find other quarter. Some of them may move in next door to you.” But as the Depression deepened, more of the industrial capacity along the Mississippi was idled and the area became a refuge for the unemployed and unhoused (as well as an incubator of radical ideas and threatening solidarities). In 1928, Bartholomew proposed a new city plan centered on riverfront redevelopment, and over the next decade that plan guided the response of the city of St. Louis to the Depression: tearing down its actually existing history and replacing it with a (hoped-for) monument.5

Bartholomew had a powerful ally in Mayor Bernard Dickmann, a real estate developer by trade, who saw the potential of the riverfront—not the potential of rebuilding it, for there was no real plan to do that at first, but the potential of tearing it down. In 1935, in the teeth of the Depression, Dickmann presented city voters with a bond issue for redeveloping (read: bulldozing) the riverfront. The immediate benefit to the city was advertised to be five thousand jobs. The mayor and his guild also looked forward to a large taking: some of them through negotiating sweetheart deals with the city for the sale of property they owned in the targeted district, others through the anticipated windfall to those who owned industrial property and warehouses elsewhere in the city. There was more than five million square feet of industrial space in the buildings along the riverfront. All of what it contained would have to go somewhere: “The absorption of this large amount of space, together with the short period of time available for procuring new locations will temporarily, and perhaps permanently, increase real estate values in St. Louis.” Led by the mayor, the real estate interest was putting the squeeze on business owners by downsizing the city, tearing down one neighborhood in order to increase the value of another. The lives and livelihoods of the people who lived and worked in the neighborhood were an acceptable cost.6

The idea of making the riverfront into a monument emerged only after the mayor and the landlords realized how much money could be made by tearing it down. If the area could be converted into a national monument, there might be federal money available for its reconstruction, and it was on the basis of a hastily agreed understanding with the president and the National Park Service that matching funds would (might?) be available for redevelopment that the mayor put the bond issue before the city in 1935. The bond issue, which was strongly supported by the realtors and the unions (especially the AFL-organized building trades, which, remember, were open only to whites in St. Louis), was presented to the city by a corveé mobilization of seven thousand city employees who were instructed by Mayor Dickmann to set aside whatever else they were doing to go door to door in support of the measure. “I hate to be a dictator,” the mayor said at the time, “but…”7

The massive voter fraud revealed by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in the aftermath of the vote makes it impossible to know what would have actually happened in an honest election, but as far as the mayor was concerned, the 1935 bond issue passed by a margin of nearly three-to-one. After a stare-down with the federal government about whether or not there had actually been any promise to match funds from the city, the mayor got his National Park Service money, and the bulldozers moved on the waterfront, beginning on October 9, 1939. “We have made every retail corner in the downtown area more valuable,” crowed one of the city’s developers in a letter written shortly after the approval of the bond issue.8

Beneath today’s Gateway Arch National Park lies the memory of the thirty-seven square blocks of the historic riverfront. Two hundred apartment buildings and houses were among the four hundred or so buildings that were torn down in the fall of 1939, almost all of them occupied by renters, many of them Black. So, too, the cluster of bars, coffeehouses, and squats that had once been known as the “Greenwich Village of the West,” the places where the poets and the radicals had met and conspired during the years of the Depression. It was almost as if Mayor Dickmann were revenging himself upon on the Black-communist-bohemian alliance that had so often demonstrated outside (and sometimes inside) his office in the 1930s.9

As many as five thousand people had jobs in the old riverfront district, at companies like Seller-Brown-Coffee, Federal Fur and Wool, and Prunty Seed and Grain—companies that reflected the city’s history as the hub of the American empire. It was only after they came down that it became apparent that there was no real plan for the riverfront—only a plan to make a plan. And so for twenty-five years the city’s planners and developer visionaries cycled through possible plans: maybe it could be a football stadium or an airport or a gigantic bomb shelter for all of the residents of the city’s downtown. In the meantime, the city of St. Louis could boast that it had the largest municipal parking lot in the world. That was not quite the architectural homage to the city’s imperial past that Bartholomew’s 1928 plan had imagined, but at least it helped with the congestion.10

If St. Louis is today known for the Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen’s Arch, which was finally built on the riverfront beginning in 1964, the city is directly encountered on an everyday level according to the vision of Harland Bartholomew’s 1947 Comprehensive City Plan. It was in this plan that Bartholomew outlined the network of expressways and arterial highways that channels the city’s traffic to this day. (The city is the only place in the United States where four interstate highways converge.) The 1947 plan also provided the basic template for the city’s zoning, separating single-family houses from apartment buildings and industrial development. Bartholomew’s plan modeled for the nation a future of suburbs, automobiles, and airplanes; it was a first draft of the material fabric of our contemporary lives. And it relied on the extensive use of the city’s “police power” in the form of zoning, as well as on novel forms of development-supporting tax abatement that Bartholomew himself had promoted and seen written into the revised state constitution in 1945.

The Comprehensive City Plan was based upon projections that the population of the city would reach one million by 1970 (and just as improbably, as it turned out, that the city and county would be administratively reunited); its thirty-one maps and fifteen tables tracked population patterns, traffic densities, and travel times and compared them to other US cities. The plan was designed around automobiles and motion: wide roads and ample parking for those commuters coming in from pleasant single-family homes in low-density neighborhoods to work in the city center, and thirty-five airports, including several heliports, to make it easy to get anywhere in the world from anywhere in the city. Bartholomew sought to reduce population density and increase access to sunlight by lowering the height of the city and expanding its limits—effectively by spreading it farther across the broad floodplain between the Mississippi and the Missouri—and to anchor its neighborhoods with parks, schools, and libraries, tying them together with a network of boulevards and scenic parkways. All in all, Bartholomew’s 1947 Comprehensive City Plan provided a beginner’s guide to building a racist city—incising and intensifying existing differences of race and class in the physical form of the built environment.11

Two of the three superhighways that would tie the downtown to the suburbs and the city to the nation were to be routed through the city’s principal Black neighborhoods—Carr Square and Hyde Park—then alongside the northern boundary of Fairgrounds Park on the Northside and straight up through the heart of Mill Creek Valley on the Southside. Planning for the construction of the superhighways began in the fall of 1943, the year when, amid the growing anxiety about the increased unemployment that would come with the end of the war, the American concrete industry recommended that highways could “contribute in a substantial manner to the elimination of slum and deteriorated areas.” While the route of the Mark Twain Expressway (Interstate 70) was eventually adjusted to take a slightly wider circuit around the Northside and thus destroy a slightly less densely populated Black neighborhood, the terms of the basic bargain remained the same when construction began in 1950: contracts for all-white contractors and jobs for all-white workers in all-white unions, subsidized access for whites to the segregated suburbs that were expanding west of the city, and destruction and displacement for the residents of the neighborhoods that stood in the pathway of progress. Not even the dead could escape civic progress: I-70 was built directly through the historically Black Washington Cemetery, requiring the disinterment of thousands whose graves were relocated to cemeteries all over the metropolitan area, in a process so haphazard that the locations of many remain a mystery today.12

As tragic as the destruction of these neighborhoods has seemed to many subsequent observers, for Bartholomew it was less an acceptable cost than a fortunate happenstance. For at the very heart of his plan was a proposal to demolish most of Black St. Louis. Of course, Bartholomew did not say that. He did not need to. There was not a single explicit reference to “Negroes” or “segregation” in the Comprehensive City Plan. Instead, there were maps and tables that outlined the deplorable conditions of the slumlord rentier–owned neighborhoods east of Grand: the density of habitation, the number of outdoor toilets, the usage of buildings built before 1900, the proportion of “sub-standard” (a term undefined) accommodations. Rather than seeing the poor conditions as an index of racist exploitation in a segregated housing market and trying to do something to build the neighborhoods up, Bartholomew simply proposed tearing them down. In the 7 percent of the area of the city he judged to be “obsolete,” Bartholomew wanted to tear everything down. That was an arc about ten blocks wide around the downtown, an area of almost three thousand acres—three times the size of Central Park in New York City, seven times the size of the French Quarter in New Orleans, almost ten times the size of the National Mall in Washington, DC, and thirty times the size of Disneyland in Los Angeles. Moreover, Bartholomew declared one-quarter of the remaining portion of the city—a gigantic arc around the center of the city encompassing about half of the Northside and a good deal of the Southside—to be “blighted” and proposed tearing down large portions of it. That was eleven thousand acres of city land: houses and apartment buildings and corner stores and insurance agencies, places where people were born and lived and worked and laughed and loved and died. All told, Bartholomew was recommending the renovation by destruction of over twenty square miles.13

It was Bartholomew’s view that the reconstruction of the city would pay for itself in the form of new investments and an improved revenue structure. During the Depression, he had employed workers from the Works Progress Administration to do a financial survey of all the city’s neighborhoods; he concluded that many areas of the city were absorbing more in city spending than they were producing in tax revenue—to the tune of $4 million annually. New businesses would be encouraged to relocate in the cleared areas around the downtown with a new redevelopment tool that Bartholomew himself had designed and promoted to the state legislature—a tax abatement, which would be included in the Chapter 353 Urban Redevelopment Act. Available only to those who planned to build in “blighted” areas of the city, Chapter 353 abatements encouraged investment by defraying the risk of such investment with an offer to entrepreneurs of a twenty-five-year real estate tax abatement. By simply tearing down all these neighborhoods, Bartholomew concluded, the city would save the $4 million a year it was spending on maintaining infrastructure from which it received no revenue in return. It could then encourage the reconstruction of those buildings on terms favorable to businesses that would contribute to the city’s economy and its revenue structure.14

It was vintage Bartholomew: necessary, logical, reasonable. Unless you slowed down to figure out what was really going on. Bartholomew had used white workers who were being paid by the federal government—white workers on the dole—to produce a report suggesting that their Black neighbors were living at the expense of white taxpayers (rather than that white intellectuals were living at the expense of the Blacks whose social life and economic plight formed the basis of their own federally subsidized salaries). From that unstable first principle, Bartholomew raced to reach what we must imagine was a foreordained conclusion: underperforming neighborhoods, virtually all of them inhabited by Black people, should be torn down and replaced with supposedly revenue-producing businesses that would be induced by tax abatements (by the government forgoing the revenue they produced, that is, but never mind…) to build in these “blighted” areas.

There was more to the story, it turned out, than that. More to it than wanting to address the poor living conditions in the neighborhoods where Black St. Louisans rented (and much less frequently owned) some of the oldest housing stock in the city, neighborhoods in which Bartholomew’s office workers had been paid to go around and count the number of outdoor toilets—89 in Compton Hill, 1,066 in Hyde Park, 3,190 in Soulard, and so on. There was more to it even than a good-government effort to help the city of St. Louis maximize its revenue so that it could build more (segregated) parks and playgrounds for its sunshine-loving (white) citizens. Besides all this, there was the fear of contagion. “This cancerous growth may engulf the entire city if steps are not taken to prevent it,” read the caption on Bartholomew’s ostensibly scientific survey map of the “obsolete” and “blighted” neighborhoods of the city of St. Louis.15

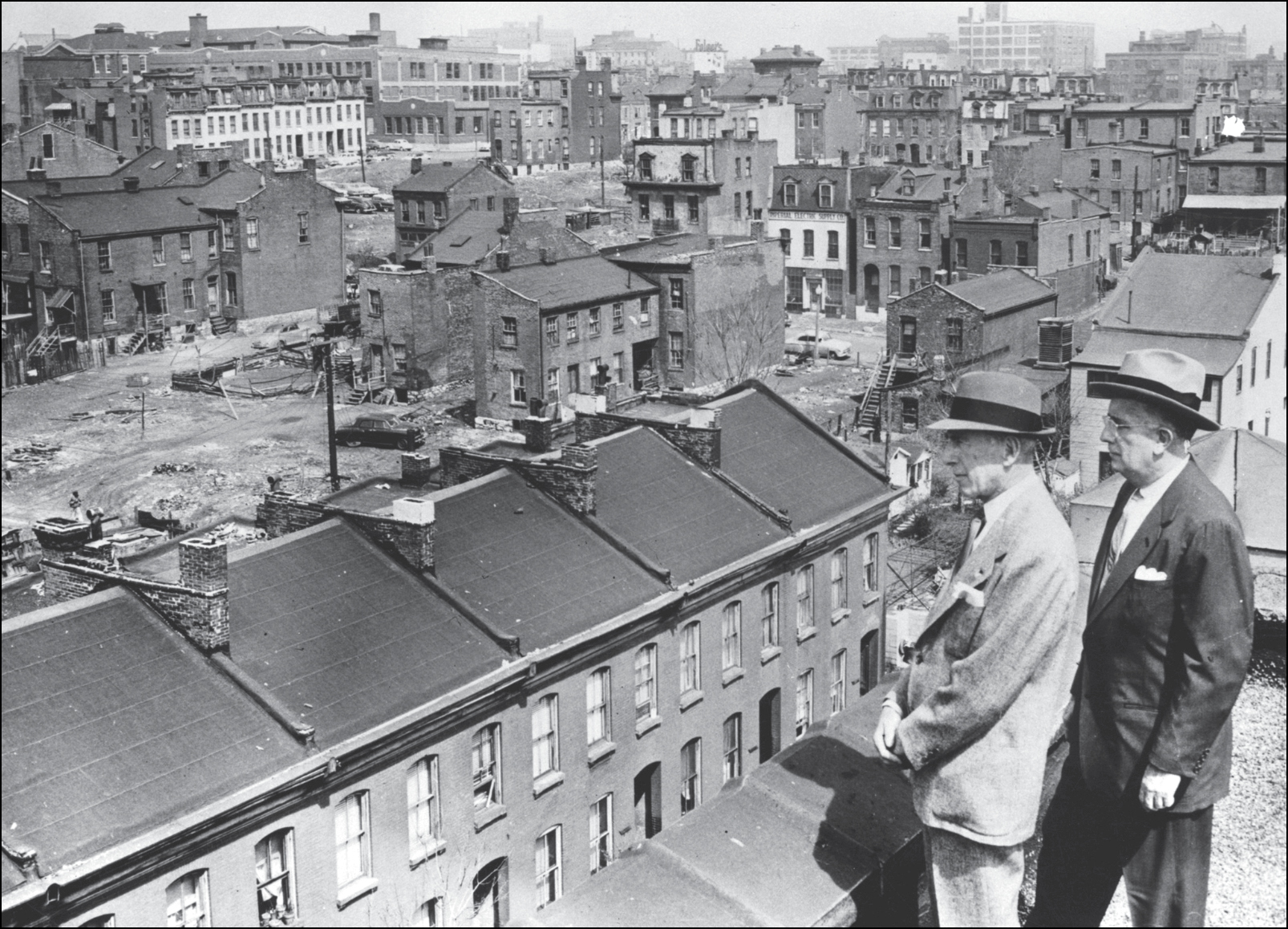

Bartholomew’s alarm was soon echoed in the press. In February 1948, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a map of the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood under the headline “Cancerous Slum District Eating Away at the Heart of the City.” Two months later, the paper published a full-page photo spread that included images of dilapidated buildings and street scenes in Mill Creek Valley; the accompanying short article noted that the Anti-Slum Commission was considering a bond issue to tear down the neighborhood. The caption of one photo contrasts the broken-down condition of the buildings on the east side of Grand to the line of tall buildings fortifying the western side of Grand. Another photo simply shows three African American children—they look to be about eight years old—on the sidewalk in front of a group of rowhouses; one of them is riding a bike. The headline is “Marching Blight”—as if those three little kids produced the architecture of segregation and exploitation amid which they lived and were planning a mission out to some white neighborhood to see if they could ruin that too.16

If there was any remaining doubt about what Bartholomew was talking about—that is, whom he was talking about—he specified that it was of the utmost importance that the “good, comparatively new residential areas in the northern, western, and southern sections of St. Louis” be protected from the changes occurring elsewhere in the city. “The enactment of the much delayed revised zoning ordinance will be extremely beneficial to these areas. Supplementing the zoning, however, there should be encouragement for the formation of strong neighborhood associations interested in protecting their character and environment”—in other words, what you or I or any reader of the Comprehensive City Plan who had even a glancing familiarity with the history and geography of St. Louis in 1947 would call “racial covenants.” That was as close as Bartholomew ever got to saying it out loud: the basic premise of his plan for the future of St. Louis, the unarticulated imperative driving the entire venture, was residential segregation.

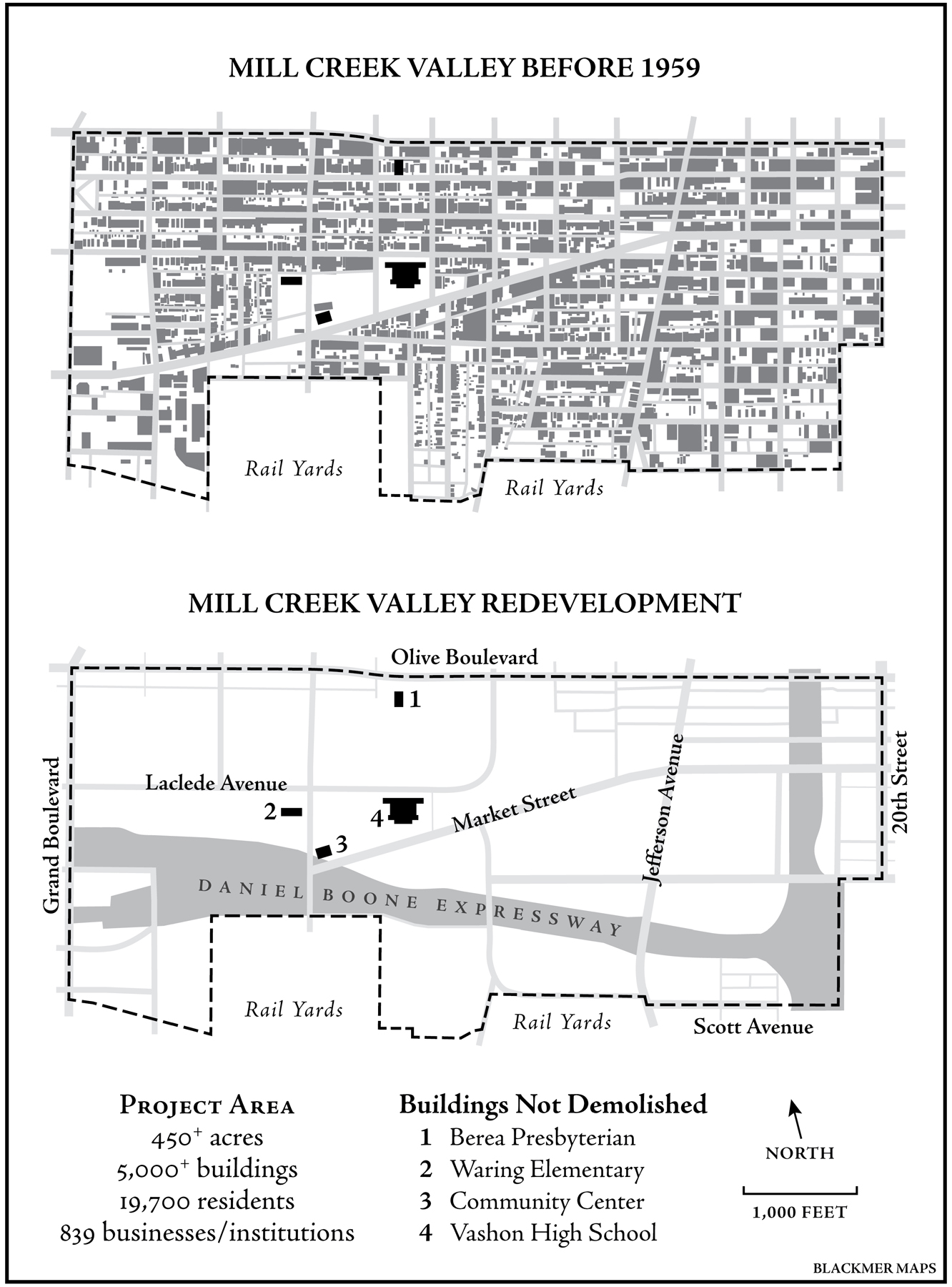

St. Louis never built the thirty-five airports and heliports Bartholomew asked for, but it did much of the rest of what the 1947 city plan called for. The city today is evidently shaped by the city Bartholomew imagined. The interstate highways are roughly where Bartholomew suggested they should be: Natural Bridge Road, Gravois, and Forest Park Parkway are the same superwide arteries connecting the suburbs and the downtown that he had used to scaffold his plan. The downtown is full of the parking lots and garages that he thought would be necessary to accommodate the quarter-million vehicles he imagined would be driving more than 2.4 billion miles annually in and out of downtown St. Louis by 1970. Following the 1947 plan, the city of St. Louis built the infrastructure of white exodus—much of it directly through Mill Creek Valley, the 471-acre area bounded by Grand to the west, Olive to the north, Twentieth to the east, and Scott and the railroad to the south. All of the one hundred square blocks—where almost twenty thousand people, 95 percent of them Black, lived in the years after the Second World War—that were marked for destruction in that sector of Bartholomew’s plan were eventually destroyed.17

The city’s adoption of Bartholomew’s 1947 plan and the rumors of its imminent destruction that soon followed put Mill Creek Valley in a deep freeze. No one wanted to buy anything there or fix anything up because they were afraid that it might all soon be torn down. “Then the realty sharks would come in,” remembered onetime resident Robert Riley. Real estate agents bought up property they knew the city would soon have to buy from them. “The technique was to come with a suitcase filled with money, new bills. Sit here, talk with you, offer you this cash money. Sign your name. They took advantage of people knowing they were going to have to move.”18 This doesn’t sound that different from the treaties that William Clark made with the eastern tribes a century and a quarter earlier and six miles to the northwest: create a climate of fear based on an imminent threat of removal and offer a short-term inducement to move with a vague promise of resettlement. Gradually, those who could afford to leave the neighborhood, or who thought they could afford to leave the neighborhood, or who could be cajoled and deceived into believing they could afford to leave the neighborhood, did. They left behind those who were too poor or too old or too bound by their families or their homes or their jobs or even their own unrealistic hopes to leave.19

There was no real plan to help any of the residents of Mill Creek Valley find homes. In October 1948, the city’s Race Relations Commission, made up of community and faith leaders appointed by the mayor, distributed a report predicting that the city’s existing plans would lead to a massive dislocation of Black residents. Noting that cities like Chicago had included relocation funds in their neighborhood-destroying bond issues, the commission suggested that the same be done in St. Louis, and in any event it demanded that the city make a moral “guarantee” to support the relocation of Mill Creek Valley residents to the city’s white neighborhoods. The city’s Progressive Party followed up by writing to the League of Women Voters asking for help in cosponsoring a conference on the housing crisis, a letter that should be read as a plea from left-of-center Blacks and whites to centrist whites for help in averting a crisis in the Black community. The letter was passed between several of the leaders of the league, each of whom penciled in possible responses before it reached the president. It sits today in a file folder housing the league’s “Slum Clearance Correspondence” file, interleaved with chummy letters from St. Louis bankers who noted their financial support for the league and urged its leaders to support the city’s effort to do something about “the sore spot at the center of our city.” How did the president of the League of Women Voters respond to the Progressive Party’s request for support in drawing attention to the plight of those who would be unhoused by the clearance plans? The penciled notation reads, “‘No’ is my answer to this letter.”20

Mayor Raymond Tucker (right) and Sidney Maestre look out over rowhouses in Mill Creek Valley. The displacement of over twenty thousand African Americans was justified as a way to reduce “blight” and replace it with “economic development.” (Missouri Historical Society)

In truth, the division of labor that had defined the previous thirty years of Black and radical struggle in St. Louis left many of the existing organizations ill equipped to confront the removalism of real estate–speculative racial capitalism after the war. Labor radicals, including Black labor radicals, had long been focused on fighting for the rights of Black workers, and much less on thinking about the condition of Black lives outside the factory gates—which is what Hershel Walker meant when he suggested that the communists should have spent more time listening and less time talking in the neighborhoods where they recruited. The unions, even those that were not themselves segregated, were focused on supporting social policies that created jobs, and Bartholomew’s plan certainly promised that, although almost all of these jobs would be in the (almost all-white) building trades. The Urban League had been decrying the condition of neighborhoods like Mill Creek Valley for more than a decade; it could hardly turn around and try to preserve it. And the NAACP, which had just won a huge victory against housing segregation in the city of St. Louis, was now faced with a plan that would ostensibly promote mixed-race neighborhoods, although no one could quite say how the people who were being displaced were going to be able to afford to live in them or overcome the white fear and violence that would be deployed to keep them out. None of the existing organizations were configured in a way that allowed them to understand and address the physical fabric of the city itself as a form of racial capitalist injustice.

The tradition of Black women’s radicalism dating back to the Unemployed Councils and even earlier might have provided some leadership, but the movement that started with the 1932 food riot had long since been superseded by all of the others. In the end, much of the city’s Black “leadership,” including the editorial boards of both Black-owned newspapers in the city, the St. Louis American and the St. Louis Argus, supported the 1955 bond issue that led to the destruction of Mill Creek Valley. The most coherent opposition was mounted by the block committees of the Urban League—the street-level neighborhood organizations through which the league was trying to transform migrant and poor Blacks into respectable workers and socially integrated city-dwellers. Only the block committees, in defiance of their organization’s leadership, resisted the destruction of their neighborhoods.21

In the meantime, the business and political elite reorganized the structure of rule in the city around the imperatives of the land grab. Thirty of the CEOs of the city’s leading firms formed an organization called Civic Progress, which orchestrated the campaign for the bond issue along with the unions, the churches, and the League of Women Voters. The measure passed by a six-to-one margin. The city, crowed the Post-Dispatch, “had voted for the new and the clean—and against the outmoded and the dirty. For a moving, growing, advancing future—and against a blighting, killing past.” The St. Louis Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority, newly created in 1951, hired a firm headed by the real estate economist and land speculator Roy Wenzlick to provide a feasibility study of the redevelopment of the 471-acre tract of land. Wenzlick recommended tearing it all down, even while acknowledging that most of the current inhabitants of the neighborhood would not be able to afford to move back after the area was redeveloped, and that “there is practically no new housing available anywhere in the metropolitan area for Negro families.” Notwithstanding the displacement of its residents, Wenzlick noted, the destruction of Mill Creek Valley would create a huge number of jobs for construction workers. And there were millions of dollars to be made—as much as $10 million from the sale of the cleared land alone.22

And so, beginning in February 1959, Mill Creek Valley structures fell before the wrecking ball: the People’s Finance Building, where Black professionals had their offices; the Pine Street YMCA, which neighborhood residents thought had the best food in the city; City Hospital No. 2; Saint Malachy Church; the offices of the Argus and the American; the Booker T. Washington Hotel; the Star, the Strand, and the London, the three Black theaters in the neighborhood; and the ballpark on the corner of Compton and Laclede, where Cool Papa Bell had played for the Negro League champion St. Louis Stars in the twenties and thirties. Also razed were homes where almost twenty thousand people had lived, stored their memories, and saved up their hopes.23

It was in these very years that southern segregationists were advocating “massive resistance” to school integration in the aftermath of the Brown decision, removing their children from public schools, and enrolling them in the “segregation academies” and parochial schools of a network that continues to serve wealthy whites today. But in St. Louis the strategy was different. Instead of massive resistance, the historian Clarence Lang has argued, there was massive redevelopment. Resistance to integration and redevelopment were not variant forms of plain and simple attitudinal bias, but variant forms of racial capitalism. In St. Louis, where the real estate interest held sway over the terms of racial governance, the order of the day was redevelopment and removal. This pattern, which had deep roots in the city’s history and was gradually spreading out in every direction from its western crucible in St. Louis, was, as the St. Louis housing rights activist Ivory Perry said at the time, “Black removal by white approval.”24

Mill Creek Valley was far from the only St. Louis neighborhood to be sacrificed to the dream of development through demolition. In the years following the Second World War, a host of St. Louis neighborhoods, all of them poor, most of them Black, were torn down, their residents scattered in the name of the public good: Cochran Gardens (1952–1953); Darst-Webbe (1954); Kosciusko (1956–1958); DeSoto-Carr (repeatedly through the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s). Indeed, the wrecking has continued down to the present day. Nor was Mill Creek Valley the only neighborhood in the nation to be sacrificed in the name of “urban renewal” in the postwar period. The bulldozer was the primary tool of postwar urban planning, especially after the federal Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954. But the wholesale destruction, population dispersion, and wanton speculation in the absence of any real plan pioneered on the St. Louis riverfront in 1939, taken to Washington by Harland Bartholomew, and epitomized in Mill Creek Valley stand out as evidence of the city’s leading role in the history of urban planning and racial removal in the United States. Long after the focus of the federal government shifted from tearing neighborhoods down to trying to rebuild and rehabilitate them, urban planners, city leaders, and business interests in the city of St. Louis remained committed to development by demolition. Indeed, they remain so today.25

Not much ever became of the Mill Creek Valley redevelopment plans. St. Louis University built a new campus on part of the tract. The campus is named for General Daniel Frost, the Confederate who surrendered to General Nathaniel Lyon at the beginning of the Civil War—a statue commemorating Lyon was removed along with everything else in the neighborhood. Eventually, the long-planned extension of Interstate 64 was built through the demolished neighborhood, providing truckers, travelers, and suburban commuters a bypass route through what the residents of the city of St. Louis came to call “Hiroshima Flats,” the name bearing witness to an earlier act of violence on an unimaginable scale. As for the residents, there had been a rough working assumption that most would be rehoused in the gigantic Pruitt-Igoe housing complex being built on the Northside. In the end, however, fewer than 20 percent of those who had lived in Mill Creek Valley found places in Pruitt-Igoe. As for the rest of the erstwhile residents of Mill Creek Valley, it is hard for a historian to provide a general answer, because there was no contemporary administrative oversight of their relocation—nobody was keeping track. It was apparently enough to know that they were gone.