11 | HOW LONG?

Everyone is polite. They speak in confidential tones of conquests. Give each other gentled names. Nothing is as it seems. Adventure means plunder. They are pirates turned captains of industry.

—COLLEEN MCELROY, A Long Way from St. Louie: A Travel Memoir

ON FEBRUARY 7, 2008, CHARLES “COOKIE” THORNTON APPROACHED Sergeant Bill Briggs on the sidewalk outside of the city hall of the inner-ring suburb of Kirkwood and shot him dead. Thornton then took Briggs’s handgun and entered the building, where the city council was in session. Over the next one minute and thirteen seconds, he shot and killed Kirkwood police officer Tom Ballman, council members Connie Karr and Michael Lynch, and city public works director Ken Yost. He also shot Mayor Mike Swoboda twice in the head; Swoboda survived the shooting, but died a year and a half later from complications related to the injuries sustained in the shooting, combined with his ongoing cancer treatment. Responding to the gunshots, Kirkwood officers ran across the street from the police station and up the stairs into the council chambers, where they found Thornton and shot him dead. Lying nearby on the floor was a placard Thornton had been holding that referred to the city of Kirkwood as a “plantation.”1

Thornton’s invocation of Kirkwood as a plantation might, on the one hand, be seen as a rhetorical convention he used to represent both the historical character and the temporal anachronism of racial injustice in the United States—we know where this comes from, and shouldn’t we be past it by now? But “plantation” also invokes the peculiarly economic dimension of that history: the extraction of white wealth from Black people. And behind Thornton’s story, it turns out, there was a history of racial extraction and dispossession: the poor and the dispossessed of the city of St. Louis being driven from East St. Louis to Mill Creek Valley to Pruitt-Igoe, then dispersed throughout the declining neighborhoods of the Northside and a few foothold suburbs in St. Louis County, and then rendered up for a final round of extraction. That history tied the history of twentieth-century Kirkwood back to Team 4, through the various expropriations of urban “renewal,” and also, arguably, to the era of Indian removal and the “white man’s country.” To anyone who might have been able to somehow see the future, that history could be traced forward in time to Ferguson—to the historical production of the conditions that framed the shooting of Michael Brown in 2014.

Cookie Thornton had grown up on the edge of Kirkwood, in Meacham Park, a small unincorporated Black enclave in St. Louis County that dated to the 1880s. Along with a small number of Black children from Meacham Park, Thornton had attended Kirkwood public schools, which were integrated by a municipal vote in 1954 following the Brown decision, and he graduated from the suburb’s high school in 1975. He attended Northeast Missouri State University on a track scholarship and graduated with a degree in business administration. After college, Thornton returned to Meacham Park, where he founded Cookco, a small demolition, construction, and paving company he ran out of his home.2

Thornton was a community leader. In the aftermath of the murders, residents of Meacham Park remembered a man who had once walked around the neighborhood greeting passers-by with hearty calls of “Hallelujah!” and “Praise the Lord!” He had go-carts, and neighborhood kids would come to his house and race them around the track in his yard. He served as an unofficial mentor for young men in Meacham Park, hiring them to work alongside him on various jobs and teaching them the trade. By the mid-1990s, he was on the boards of the Kirkwood-Webster YMCA, the Kirkwood Historical Society, and the Kirkwood Housing Authority. Through Project 2000, one of several charitable organizations in which Thornton was active, he mentored children at a nearby elementary school. And in 1994, after Meacham Park was annexed by Kirkwood, he ran for a seat on the city council; even in defeat, he sounded optimistic: “I was just getting my feet wet,” he said. “I just wanted to let folks know that there are qualified people from Meacham Park who are willing to participate in Kirkwood government.”3

And then, sometime around the year 2000, things started to go sour. The city started ticketing Thornton: for parking his dump truck on his lawn, as he always had; for not properly posting work permits on jobs where he was working; for the type of signage he had on his property. As a neighborhood of the city of Kirkwood, Meacham Park was now subject to its municipal code. The fines started to add up, and by the end of 2001 Thornton owed the city over $12,000 in fines; in all, by 2008, he had received over 100 tickets, and owed almost $20,000—a total that is hard to understand as anything other than a massively disproportionate and punitive response to Thornton’s claim (albeit a stubborn claim) of a long-standing customary right to do business in the way that he always had.4

Thornton began to attend city council meetings, speaking at length about the city’s code enforcement and accusing city officials of racism. When the council passed an ordinance limiting citizens’ comments to three minutes apiece, Thornton began to disrupt the meetings by walking past the microphone and addressing the council directly. When the council passed an ordinance confining the public behind a blue velvet rope placed at the front of the gallery, Thornton began to lie down in the aisle and bray like a donkey. When the council ordered him removed from the chambers, he went limp, forcing the city officers to pick him up off the ground and carry him out. In 2001, when Ken Yost, whom Thornton would kill in 2008, approached Thornton in his yard, Thornton threw some straw at him. Yost called the police, and Thornton was convicted of assault.5

In the aftermath of the massacre, many in Kirkwood thought Thornton had simply lost his mind. Thornton’s brother saw it differently. In 2008, Thornton had once again been charged with assault, this time for tripping a man who had confronted him during a one-man demonstration outside a bar where the city attorney was known occasionally to have drinks. By that time, Thornton had lost his business and mortgaged his house in a long and unsuccessful legal battle with the city of Kirkwood and its racist fines. He thought he was out of legal options and likely to go to jail. “My brother went to war,” said Gerald Thornton in the aftermath of the murders.6

Meacham Park became part of the city of Kirkwood in 1992, after voters in both polities approved the annexation by a margin of almost three-to-one. For voters in 97 percent Black Meacham Park, annexation came with the promise of better public services—many of the roads in the neighborhood were unpaved, and there were no streetlights—as well as better fire and police protection—five children had died in a house fire in Meacham Park when the impoverished fire district’s truck would not start. For voters in 92 percent white Kirkwood, “the Queen of the Suburbs,” where the average income was almost four times that in Meacham Park and the average home was worth almost three times as much, the annexation was publicly presented as an opportunity to do the right thing. But lingering in the background was the possibility of economic development. As the then-mayor of Kirkwood put it in 1994, “the citizens who voted for annexation voted for redevelopment.” Of course, that left open several questions: What sort of redevelopment? With what sorts of benefits for what sorts of people? And with what sorts of costs for what sorts of people? Or as one of the residents of Meacham Park put it, “They annex us and then within two years they crawl into bed with [developers] and are ready to move us out of our community.”7

The answer at the bottom of the chain of questions about Kirkwood’s annexation of Meacham Park was a shopping mall. Bounded by an interstate on one side, a state highway on another, and a major east-west arterial street on still another, Meacham Park was a somewhat isolated place to live, as it was supposed to be, but it was a terrific place for a Walmart. When residents later expressed horror at the proposal for the shopping center that would eventually be built on the bulldozed remains of about half of their neighborhood, then-mayor Marge Schramm reminded them that she had always said “that development would be necessary to get the improvements to the neighborhood that were wanted.” In fact, the city of Kirkwood was hoping to eventually draw as much as $3.5 million a year in tax revenue from paving over thirty-six acres of Meacham Park and signing a deal with the Opus Group of Minneapolis to build a shopping center—a deal so good that it later became apparent that the city had offered Opus all of Meacham Park, only to be told that half would be enough.8

There were promises made in return: $150 million in taxable business; seven hundred short-term construction jobs; six hundred permanent jobs; housing upgrades for residents who were able to stay in their homes; fair-market-value purchase of the homes of those who lived in the pathway of progress; new housing within the boundaries of Meacham Park at affordable prices for those who were displaced; and the transformation of the long-closed James Milton Turner School, named for the Reconstruction-era educational reformer, into a community center. It was enough to convince many of the residents of Meacham Park to cast their lot with Opus. Of course, it all turned out to be hogwash—or, if not hogwash, a sort of diluted runoff that still smelled like hogwash and was too dirty to wash away the wrong of it all. In the end, the mall project destroyed more than half of Meacham Park, taking at least ten more full blocks than in the original plan presented to the residents. A promised eighty-five new houses became six. The Turner School was never converted into a community center—on the site today sits a high-end rehabilitation facility that caters to professional athletes from across the continent. And on the day the city signed the final agreement with the developer, several of the residents who thought they were still in the middle of negotiations over the price they would get for their houses found condemnation notices taped to their front doors. For Opus, it was just business: “Obviously, we’ve got a schedule to meet, and we’ve got to give people a wake-up call,” said a spokesman for the company.9

In Meacham Park, even those who had once been supporters of the project began to feel as if they had been taken. Bill Jones, who had accused those who opposed the mall of wanting “to throw Meacham Park back into the Dark Ages,” said that he felt “sold down the river” by the condemnations: “What kind of plantation do they think they have out here?” The conflict over the condemned houses was enough to get Opus to pull out of the deal, but it was revived under the supervision of the DESCO Group, headquartered in Clayton, and construction began in 1995. On the site today sits Kirkwood Commons (the irony of the name is so obvious that it is hardly worth the words it would take to express it): 209,703 square feet of retail space, including Walmart, Lowe’s, Target, Buffalo Wild Wings, Sonic, and White Castle, and almost three thousand parking places. Where there used to be several ways to get in or out of Meacham Park, now there are only two, the others having been closed off by the mall; one leads northward, onto Big Bend, and the other snakes around the back of the mall and then debouches in the far end of the parking lot.10

And yet, through it all, up until ground was broken, Cookie Thornton was a supporter. Neighbors remembered Thornton working on behalf of the developers, trying to convince resistant neighbors to negotiate terms of sale for their condemned houses. Virtually everyone in Meacham Park thought that Thornton had been promised work on the project in return for his support, including Thornton himself. Part of the pitch, after all, was that the mall project would bring seven hundred construction jobs to Kirkwood, and there were suggestions that priority would be given to Meacham Park residents in hiring. Indeed, Thornton claimed that he had been told by the mayor that he would be hired to do some of the demolition; she would later say, effectively, that she had just dangled the possibility without making a promise that would not be hers to keep. In any case, Thornton bought himself a new truck so as to be a credible candidate for the work he thought was coming his way—the very same truck that the city of Kirkwood began to ticket five years later, after it became clear that neither DESCO nor the city of Kirkwood was ever going to hire him to do anything. When the jobs were finally allocated and the contracts signed, Thornton was cut out of the work. As one of his neighbors remembered in the aftermath, “Cookie’s biggest problem was he was one of the proponents of the annexation with Kirkwood.… Then they turn around, he don’t get none of the contracts, he don’t get none of the money.”11

From the perspective of the Kirkwood city government and DESCO, it was simply business as usual: “I know we strongly urged that he be included in minority businesses—we did require a certain amount of work for minorities. But that’s not just Cookie,” said the mayor. Thornton had made a bet on “Black capitalism,” on the promise of a piece of the action, and he had tried to sell his neighbors on the same promise. But when the time came to share the spoils, he was simply another Black cipher recorded on the page of a faraway account book—someone, a “minority” someone, who might be compared to other minority someones in a decision that came down to dollars and cents in the pockets of people who cared more about calculating the bottom line than taking the high road. It was then that Thornton began to split from the program and descend into the dark cycle of feelings of humiliation, betrayal, anger, and fear that led him to the city council chambers on that February night in 2008. “I think that Cookie was promised a lot and that he was lied to,” remembered one of his neighbors, trying to make sense of things. “He was used and manipulated, and once he figured it out, he became irate, because he was hurt and disappointed. I think he really thought he could trust certain individuals and he just snapped.” By the time he armed up and set out for city hall, he had lost his wife, his house, and a federal court case against the city of Kirkwood, which he had mortgaged his parents’ house to pay for. He had nothing left to lose.12

According to the journalist who wrote with the most depth and sensitivity about the murders, white people in Kirkwood were shocked that such a thing could happen to them. People for whom the city wasn’t “just a place, but a dream, a vision of how life should be,” found themselves asking, “How could this happen here?” Their puzzlement was a distant echo of that experienced by the residents of Meacham Park when the annexation was first proposed: “When Kirkwood first came to annex us,” remembered Harriet Patton, who ended up leading the effort to forestall the mall project, “we asked why do you want us?” After all, cities like (and including) Kirkwood had spent decades trying to keep Black people from settling within their city limits; for many years, the nicest thing that anyone in Kirkwood seemed to have to say about Meacham Park was that it should be torn down. But something had changed by the time of the annexation and the mall project—something that had politicians and developers all over St. Louis trying to figure out ways to leverage small and isolated populations of poor Black people into large economic gains. As an oft-repeated commonplace in Meacham Park had it, “Kirkwood pretty much ignored us, until it found a way to make money off us.”13

Since 1974, federal aid administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development has been structured in the form of community development block grants. This program is based on the assumption that, rather than support specific projects—the destruction of the waterfront, for example, or the construction of Pruitt-Igoe—the federal government should allocate money to cities on the understanding that decisions about spending are best made on the local level. The block grant program emerged as a compromise between conservatives who could see it as part of President Gerald Ford’s New Federalism, a way of diminishing federal involvement in state and local affairs, and liberals who could see it as a way of empowering community-based organizations by giving them control over their own lives and affairs. Unfortunately, in St. Louis, as elsewhere in the nation, city leaders often saw the program as a way of monetizing their population of poor and Black people to benefit their wealthier and whiter neighbors.14

Community development block grants were created with the stated purpose of supporting the economic development of low- to moderate-income residents of American cities. With a low degree of federal oversight (that was the point of the New Federalism) and a fairly high degree of local connivance, the CDBG program was soon transformed into a discretionary fund to support whatever type of economic development city governments thought might benefit their cities overall. In St. Louis, that meant focusing on the central corridor and skimping on the Northside as it devoted its efforts to building a city that was friendly to business rather than to Black people. In the first ten years of the program, the mayor’s office allocated the same amount of federal money to the four wards between downtown and Forest Park as it did to the twelve wards on the city’s Northside; at least 50 percent of the CDBG money spent in the city, according to the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), was spent to subsidize either business owners or gentrification. Testifying before a federal court about segregation in the St. Louis schools in 1981, the political scientist Gary Orfield described the recent history of the city’s disbursement of federal money through block grants as “yet another chapter in the long epic of federally-funded, locally administered residential segregation and re-segregation.”15

By 1991, the city’s inequitable CDBG spending had achieved a level of notoriety so great as to trigger a federal audit. The immediate cause was a $650,000 advertising campaign designed to lure new residents to the city—an expenditure that was not allowable under even the very broad and rarely enforced limits of the program. “We have no requirement that a community spend even one dollar on housing,” said the local overseer of the federal program, so cities could waste all the money they wanted, as long as they were careful to “waste it away properly.” Emblematically, the city’s improper waste was a campaign to gentrify the Northside of the city by luring nonresidents to move there, complete with a brochure that papered over the poor and Black daily life of the Hyde Park neighborhood with a black-and-white photo of a white family having a picnic in Hyde Park in… maybe 1940?

Alongside the improper waste, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch followed up with a series of articles that documented an extraordinary level of proper waste—waste that was legally allowable but morally unconscionable: $8,000 to equip the mayor’s niece and several of her coworkers, who were overseen by the mayor’s sister, with car phones so that they could provide one another with up-to-the-minute information about the condition of vacant lots in the city; 101 subsidized house rehabilitations for homes that sold for an average price of $90,000 (about $175,000 in 2020 dollars, and thus well beyond the reach of low-income or even moderate-income St. Louisans); $330,000 to a home repair agency that employed more clerical workers than carpenters. In response to the question of whether someone in the city government should have walked around to check that grant recipients were spending money the way they were supposed to be spending it, St. Louis mayor Vincent Schoemehl replied that calls for that type of oversight represented a “nineteenth-century mentality.”16

The underlying drift of the spending was apparent to anyone who walked around the wards of the city. Although the federal money had been justified largely by the Black poverty on the Northside, a majority of those funds were nevertheless being spent elsewhere in the city on—not to put too fine a point on it—white people. The largest single portion of federal grant money in the city of St. Louis, according to the Post-Dispatch investigation, was spent on the administration of federal grant money—almost 20 percent. The report further suggested that as much federal money was being spent in the city’s wealthiest four wards as in its poorest twelve—and the latter, far from being distributed between those twelve wards, was concentrated in areas of the impoverished Northside adjacent to the wealthy Central West End. Moreover, most of the money directed toward actual bricks-and-mortar redevelopment of the city was spent in the city’s wealthiest central-corridor neighborhoods. Meanwhile, spending on the city’s poorest neighborhoods generally went to social programs—a disjuncture that some found akin to simultaneously investing in deepening structural racism while taking credit for addressing some of its most egregious surface symptoms.

Seen from the Northside, the spending of federal block grant funds seemed to follow the prescription of neighborhood triage outlined by Team 4 in 1979: invest in the wealthy neighborhoods, shore up the borders, and put the rest of the city in a deep freeze. The implication that the Team 4 plan had anything to do with the administration of the city in the 1990s was (and is) bitterly resented by Mayor Schoemehl, who explained his allocation of federal funds intended to support housing for low-income people to many of the wealthiest neighborhoods of the city instead in the following terms: “I just don’t believe the city of St. Louis should become the region’s final repository of all the poor, unemployed, and undereducated.”17

The last decades of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first were unkind to the economy of St. Louis. The 1973 oil embargo and the 1979 recession (spurred by the mercilessly high interest rates maintained by Paul Volcker at the Federal Reserve in response to the inflation of the 1970s) led to the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression—up to 20 percent for Black workers, according to government measures, a figure that is conventionally taken to measure only half of the actual level of unemployment. Because of its large role in the defense industry St. Louis was partly insulated from national trends by the Reagan-era defense buildup. Emerson Electric’s company history describes these as lean years backstopped by increased orders for TOW missile launchers; McDonnell-Douglas in these years was in the early development stages for the A-12 Avenger, a long-range stealth bomber for the US Navy that would never be built, a failure that contributed to the company’s later demise and eventual sale to Boeing.18

The 1980s was the era of deregulation and corporate raiding. Regional companies that had once thrived in St. Louis—Brown Shoe, the Stix, Baer & Fuller and Famous-Barr department stores—were gobbled up or displaced by larger super-regional competitors unleashed from the antitrust laws that had once protected against consolidation. Boatmen’s Bank, which once claimed to be the oldest bank west of the Mississippi, was purchased by NationsBank in 1996, which was in turn acquired by Bank of America in 1998. (Jefferson Bank is still locally owned.) Transworld Airlines was acquired by Carl Icahn, the era’s emblematic corporate raider, who first bought up Ozark Airlines, once hubbed in St. Louis, and then gradually stripped and sold off TWA until the airline that had once accounted for 80 percent of flights in and out of St. Louis and a full half of transatlantic flights to and from North America was run into the ground and bankrupted in 2001. With fewer and fewer flights at higher and higher prices, the city became harder to reach at the very moment when the global economy was being reordered around a few increasingly influential “global cities.” McDonnell-Douglas, meanwhile, shed nineteen thousand employees between 1989 and 1996, when it was acquired by Boeing. When Boeing missed out on the contract for the Joint Strike Fighter in 2001, it laid off seven thousand more St. Louis workers.19

A final wave of acquisitions around the millennium and after resulted in the selling off of the city’s heritage firms to global conglomerates. Longtime St. Louis stalwart Ralston-Purina was bought by the Swiss firm Nestlé in 2001, and in 2008 Anheuser-Busch, a company so synonymous with St. Louis that its television advertisements ended with the words “Anheuser-Busch, St. Louis, Missouri,” became a wholly owned subsidiary of the Belgian firm InBev. Monsanto, perhaps the most notorious company in the world, held out the longest, producing herbicides and genetically modified crops across a global empire headquartered in Creve Coeur up until its purchase by Bayer in 2018. Among the landmarks in its corporate history were the artificial sweetener saccharine, the insecticide DDT, the pesticide Agent Orange, coolant PCBs, and the genetic modification of bovine growth hormones. Although the St. Louis metro region can boast of an unparalleled ground transportation network—four interstate highways supported by several interstate bypass routes converge in the city, a relic of Harland Bartholomew’s soul-sucking influence over both regional and national development—it has struggled to compete in the increasingly deindustrialized, financialized, and globalized economy that has emerged over the past forty or fifty years. In 2006, the Ford Motor Company closed its Hazelwood plant in North County, which had employed around five thousand workers, and the exodus continues to this day. Among the largest employers remaining in the city today are the hospitals and Washington University—nonprofit institutions that pay no property taxes—and Peabody Coal, one of the nation’s most notorious companies, a legacy firm that ties the city’s economy back to its origins in the imperial extraction of Indian country.20

In Missouri, this global winnowing was accompanied (some might say exacerbated) by state-mandated fiscal austerity. As political leaders in the city and the county tried to make their region more appealing to increasingly mobile firms in an era of increasingly concentrated ownership, they had few tools at their disposal. Spurred by the example of California’s passage of the tax-capping Proposition 13 in 1978, Missouri added an amendment to the state constitution that pegged future taxes in the state to the 1980s ratios of state revenue to aggregate state income and mandated that any future relative increases to local taxes be approved by full municipal referendum. The campaign for the amendment was led by future Missouri congressman Mel Hancock and his Taxpayer Survival Association, whose melodramatic name signals the appeal to white property owners that was central to Hancock’s success. Under the Hancock Amendment, it is difficult for cities in Missouri to raise taxes on existing property-holders in order to provide the amenities necessary to draw new businesses (and hence new revenue) to the community. And hedged in by the hard boundary between county and city established in 1876, it is impossible for the city of St. Louis to capture revenue from adjacent areas through annexation and incorporation. Faced with these limitations on how it might raise revenue in a virtuous cycle with economic development, the city of St. Louis, along with municipalities all over the United States, has hit upon a seemingly paradoxical solution: rather than raising more money, they can simply give it away.21

In 1945, at the urging of municipal leaders and real estate developers looking forward to the clearance of Mill Creek Valley, and under the stewardship of Harland Bartholomew, the Missouri State Legislature passed the Chapter 353 Urban Redevelopment Act and the Chapter 99 Land Clearance Act. Chapter 353 provided tax abatements for those who developed “blighted” property in the city; for the first ten years that property would be taxed at its predevelopment, or “blighted,” value, and for the next fifteen at one-half of its postdevelopment assessment; only after twenty-five years would its value come fully onto the books. Chapter 99 provided for the redevelopment of entire neighborhoods of the city by making them city property. The city often paid for substantial improvement and then leased the improved sites to new businesses, thus subsidizing the costs of customization while relieving those who built businesses on the redeveloped land of the obligation to pay property taxes and bearing much of the risk of failure.22

The original tax abatement laws defined “blight” as “that portion of the city within which the legislative authority of such city determines that by reason of age, obsolescence, inadequate or outmoded design or physical deterioration have become economic and social liabilities, and such conditions are conducive to ill health, transmission of disease, crime or inability to pay reasonable taxes.” In the lexicon of urban politics in St. Louis, however, the word “blight” is a verb, usually in a sentence whose subject is a developer with a big idea and some friends in the city government and the object is a Black neighborhood. Thus, in 1959, after considering the reports from Harland Bartholomew and Roy Wenzlick & Company, the city of St. Louis blighted Mill Creek Valley. That is to say, the city declared that after the destruction of Mill Creek Valley, the area would be made available to developers on favorable terms. Through the 1960s and 1970s, much of the most notable development in the city was subsidized by Chapter 353 tax abatements, including the transformation of Laclede’s Landing along the waterfront into an alternative downtown entertainment district more accessible by car than by foot from the actual downtown in 1966; the commercial redevelopment of the old Union Station, the onetime heart of Chestnut Valley, in 1974; and the building of the Washington University Medical Complex at the east end of Forest Park in the same year. All of this development, some of it successful and lasting, some of it not, had no short- or even medium-term impact on the city’s real property taxes.23

In St. Louis, a great deal of the blighting was done near the Arch and in the long shadow of the 1904 World’s Fair, the idea being that the city’s pathway back to greatness was to become a destination city for tourists. In 1968, Mayor Alphonso Cervantes used Chapter 99 to blight much of what had once been Deep Morgan in order to relocate the Spanish Pavilion from the 1964 New York World’s Fair to St. Louis, complete with a replica of Columbus’s flagship, the Santa Maria. Shortly after the project was completed, the faux Santa Maria broke free from its moorings on the Mississippi during a storm and drifted out into the river, finally crashing into the shore, capsizing, and sinking amid the abandoned docks on the east side of the river. The relocated Spanish Pavilion met much the same fate, at least commercially speaking: it was shuttered in 1971.24

Much of the area was eventually developed into the TWA Dome—later the Edward A. Jones Dome and today the America’s Center—under Chapter 100, a successor program that allowed the city to sell bonds in order to pay for the redevelopment of property that would then be leased to commercial tenants. In 1995, Mayor Freeman Bosley Jr., the city’s first Black mayor (and son of the alderman who had fought for the hospital), used the promise of a downtown domed stadium owned by the city to lure the Los Angeles Rams to relocate to St. Louis—a deal that, at least for the week after the Rams won the Super Bowl in 2000, seemed like a coup. The underlying financial structure of the deal, however, suggested the circular downward flow of another sort of bowl—at least as far as the city of St. Louis was concerned. Because the facility was municipally owned, the city of St. Louis became responsible for its maintenance and improvement, and under its contract with the Rams the city was obligated to provide a stadium that was in the “top quarter” of NFL stadiums. For some period of time the Rams ownership “allowed” the city to simply make cash payments—amounting to around $70 million, all told—instead of improving the stadium. But eventually, in 2015, billionaire owner Stan Kroenke, heir by marriage to the vast fortune of Walmart founder Sam Walton, used the condition of the stadium as grounds to move the team back to Los Angeles, leaving the city of St. Louis as the owner of a 67,000-seat stadium in which to host horse shows and church conventions, as well as $144 million of debt still to be paid on the bonds that it had issued to pay for the stadium in the first place. In sports management circles, the deal Kroenke made with St. Louis is known as “possibly the most sweetheart lease of all time.”25

Property tax abatement—whether through the municipal ownership of commercial property (Chapter 100) or through the negotiation of extended tax amnesty (Chapter 353)—was intended to be a way to raise revenue under the austere terms of the Hancock Amendment. The city of St. Louis repeatedly agreed to forswear tax collection in the hope that this kind of subsidized development would provide other sorts of revenue or greater revenue down the line. The city, that is to say, pursued a paradoxical strategy structured by perverse incentives, starting with a long-term incentive toward gentrification, because in the absence of the ability to raise taxes, the best way to raise revenue was to raise property values. This is a problem (and solution) bedeviling many American cities today.

But in St. Louis, these long-term incentives have been mostly set aside by the short-term pursuit of increased revenue from sales and earnings taxes rather than from increased commercial activity and new jobs. As with other aspects of abatement-based development, even these revenue gains, when there are gains at all, come at a terrible price—a price that is much greater than the one-to-one calculation of dollar of property tax abated in return for a dollar of sales tax gained by which they are usually justified. Property taxes are progressive (thus falling more heavily on the rich) and are earmarked for schools, while sales taxes are regressive (thus falling comparatively more heavily upon the poor) and flow into the city’s budget for general operating expenses. As the sociologist George Lipsitz put it, when the Rams defeated the Tennessee Titans in Super Bowl XXXIV, the people of St. Louis celebrated quarterback Kurt Warner, running back Marshall Faulk, wide receiver Isaac Bruce, and head coach Dick Vermeil—“the Greatest Show on Turf”—“but no one publicly recognized the contributions made by the 45,473 children enrolled in the St. Louis city school system.”26

In the beginning, tax abatement under Chapters 99, 100, and 353 was used to accomplish the sort of “Negro removal” decried by Ivory Perry. Mill Creek Valley, the Maline Creek area of Kinloch, North Webster Groves, and Elmwood Park (near Olivette) were all Black areas of the St. Louis metro area that were “blighted and… eradicated” in the name of development between the 1950s and the 1990s, a process that continues all along the frontier of gentrification to this day.27

Meanwhile, on the other side of the frontier, poor homeowners are losing homes on which they cannot afford to pay the property taxes. As of this writing, the city’s Land Reutilization Authority holds over twelve thousand properties in the city, the vast majority of them on the city’s Northside, and the vast majority of them seized by the city in lieu of unpaid taxes. While many of the properties were undoubtedly abandoned for reasons other than their owners’ inability to pay their real estate taxes, it is nevertheless profoundly ironic—malignantly ironic—that poor Black homeowners lose their houses over unpaid real estate taxes in a city where much of the commercial property held by wealthy firms is completely tax-exempt. And the irony deepens: the city itself is too broke to keep the property it has seized up to code—its own code—and so thousands of parcels of property sit boarded up, deteriorating, and abandoned while a large number of unhoused people sleep on the streets.28

Over the 1990s, the dialectic of economic development and Black removal that had arguably prevailed for most of the twentieth century was transformed into one in which developers used the proximity of Black people—some of them in pockets that remained in the wealthier neighborhoods and suburbs of the city, some of them refugees from previous waves of displacement and development—to justify the state subsidy of private development. Rather than concentrating on large projects like Mill Creek Valley or Laclede’s Landing or the downtown stadium, developers began to pitch smaller projects located all over the city. And rather than the removal of Black people, these projects depended on their presence: small numbers of poor Black people living within a reasonable distance could be used to justify tax abatements—sometimes very large tax abatements—no matter whether or not the proposed projects would actually improve the overall condition of the area.

In a series of rulings in the 1970s, the Missouri Supreme Court had widened the definition of “blight” to include property that was not itself blighted but was near a blighted area included in the plans for redevelopment. That is to say, they made it possible to gain tax abatements over a span of parcels that joined together a large number of tracts with favorable commercial prospects and a sampling of “blighted” property. In the years between 1997 and 2008, Chapters 99, 100, and 353 were used to blight, abate, and develop over nine hundred parcels of property all over the city. During this period, almost one-third of the ordinances passed by the Board of Aldermen were enabling ordinances that spot-blighted this or that piece of property in an improvisational, developer-driven pattern that addressed inequality in the city in only the most cursory fashion.29

When you arrive in St. Louis today and drive east on I-70 from Lambert–St. Louis Airport to the downtown, one of the first sights you encounter is the massive Express Scripts campus. It sits on either side of the highway, within the boundaries of the Normandy School District, from which Michael Brown graduated in the spring of 2014. Until 2018, when it was purchased by Cigna, Express Scripts, a prescription medicine provider, was the highest-grossing corporation in Missouri, and its CEO was the highest-paid executive in the state. All told, the campus is 496,000 square feet, complete with two large parking lots to accommodate workers driving in on the interstate from the county and elsewhere; indeed, part of the construction for the project included building new access roads to make it easier for commuters to drive to and from work. Construction of the complex was subsidized by Chapter 100 and Chapter 353 tax abatements. According to a University of Missouri–St. Louis study published in 2014, the company received a total of $63 million in tax incentives related to its new headquarters.30

Noting that the payroll tax revenue that the state received from Express Script employees was far greater than the subsidy the company received, the study concluded that the subsidy had made sense from the perspective of the state of Missouri, and perhaps it had. But the project unquestionably represented a transfer of revenue from the Normandy schools to the Missouri State Legislature—a transfer, that is to say, to white Republicans (and ultimately rural whites) from a 97 percent Black school district that had an equal number of students eligible to receive free lunch and that lost its state accreditation the same year Michael Brown graduated from the high school. Though the Express Scripts campus sits within the boundaries of the Normandy schools’ tax-catchment area (adjacent to the Ferguson-Florissant District), for Michael Brown and his fellow students, because of the abatements, the construction of the half-million-square-foot headquarters of a multibillion-dollar corporation (Cigna paid $69 billion for Express Scripts) in the neighborhood mattered not at all. Indeed, once the Normandy School District lost accreditation, its students were allowed, under state law, to transfer to schools in nearby suburban districts—provided that the Normandy School District paid those districts $20,000 per student, a good deal more than the Normandy district received per student in revenue. Thus, for the past five years, the Normandy School District, already cash-strapped, already struggling, has been subsidizing the schools in Clayton, Ladue, and other wealthy St. Louis County school districts.31

Since 1982, much of the subsidized development in the city of St. Louis has been supported by tax increment financing (TIF). Tax increment financing allows cities to sell bonds on behalf of developers. The bonds can be used to pay for feasibility studies and environmental impact studies and to assemble property, construct public works, rehabilitate or remodel old buildings, or even build new ones—to cover all of the costs of development. Property taxes in the TIF district are frozen for a period of time (twenty-five years in Missouri), and would-be property tax revenue above that zero-year threshold, the “increment” of revenue gained by development, is diverted into a fund to repay the bond. One-half of the sales and income taxes harvested from those who shop or work within the boundaries of the TIF are also diverted for that purpose, following a 1998 law. The theory is that the revenue produced by development will be great enough to cover the costs of the bond, and that the city and the state will eventually be able to gain revenue from the development they have financed on behalf of the developer.32

Like tax abatement, TIFs are justified as policy tools for addressing “blight” and as ways of encouraging investment in places where capitalists might otherwise be reluctant to take risks as well as harnessing the power of capitalist development to enhance the general welfare. The standard by which judgments were to be made as to whether existing buildings, neighborhoods, and even open land in the city were blighted was the “but for” clause—a required attestation that “but for” the state subsidy, the proposed investment would not occur. Leaving aside for a moment the philosophical imponderability of whether something would or would not happen in the absence of something that was already actually present as an inducement to its happening, it is perhaps enough to say that the “but for” clause has given developers in the St. Louis metro region (and the rest of Missouri) extraordinarily wide latitude in defining “blight” and gaining public subsidies for private development. The clause has also had the perverse effect of making “blight”—and thus Black people, the stereotypical signifiers of urban “blight”—valuable to developers. That’s what happened in Kirkwood.33

The art of the TIF is in the drawing of the district. The more commercially vital the district, the better the result is likely to be for all of the principal actors: the developers, who are able to unload many of the sunk costs (and hence much of the risk of development) onto the city and state while still building in a location where they can make lots of money; and the city and state, which, in absorbing the risk of the development, are betting on its success. And so the drawing of TIF districts has come to resemble the practice of gerrymandering political districts. Enough blight must be included in order to meet the (admittedly very loose) legal standard, but the viability of the project is assessed by how much economic potential can be harnessed to the enabling blight. Recall the sentiment expressed in Meacham Park: “Kirkwood pretty much ignored us, until it found a way to make money off us.” What was intended, or at least justified, as a project that would put the power of economic development behind community development has instead been turned inside out. Black populations—not Black communities, not Black people, not Black labor, but Black populations—have been conscripted to the cause of corporate subsidy. “Ain’t nothing changed but the year,” said one resident of Meacham Park after the annexation and the construction of the shopping mall. “It was more about the money, a tax bracket, and Kirkwood Commons.… To me that’s all it was ever about,” he said, “dirt roads… and dirt-road pimping,” referring to the poor and unchanging conditions that continued in Meacham Park and had been used to justify the TIF.34

In theory, these incentives do not cost taxpayers any money. Cities issue the bonds feeling confident that the new businesses will generate more than enough revenue to pay the money back. The problem is that the amount the city must pay each year is locked in at the beginning of the bond issue. If the increased revenue is not as high as expected in any given year, the city finds itself in the red. Tax increment financing is a way of indenturing municipalities to their own hypothetical economic development. Actually, it’s even worse than that. The municipal bonds issued by cities like St. Louis (and, we will see, Ferguson) are bundled and sold on a secondary market, in much the same way as the bundled subprime mortgages that figured so prominently in the financial crisis of 2008. The purchasers of these bonds then become, in effect, the creditors of the cities that have issued them. Municipal bonds are generally a good investment, for multiple reasons. First, under federal law, the interest they pay their holders is tax-exempt. Second, municipal bond-holders have the legal status of first-paid creditors: before a struggling city fixes its roads, or pays for the new park or the school on Main Street, it is legally obligated to pay the investors on Wall Street.

The result has been a catastrophic parody of the idea that the rising tide of economic development will lift all boats. Because of the constraints that cities face in raising revenue, TIFs have been disproportionately used to fund retail development, which at the very least provides cities with sales tax revenue (even if it comes at the expense of diverting revenue from schools to general operating funds). The most notorious example is perhaps the Des Peres Mall, built on the site of another West County mall in 2002. In spite of the fact that Des Peres had a median family income of over $100,000 at the time of the mall’s construction, the existing mall was almost 100 percent occupied, and it was grossing over $1 million a year, the city of Des Peres created a $29 million TIF to subsidize the construction of a new mall, which, it should be pointed out in all fairness, would include both a Nordstrom and a Lord and Taylor.35

Perhaps Des Peres was worried about the Galleria Mall; built with TIF funding six miles away in Richmond Heights in 1984 and expanded with another TIF in 2016, the Galleria was wedged in between two of the metro area’s most prosperous cities, Ladue and Clayton. There is no doubt that there was fierce competition between the malls to draw shoppers from the Orion Apartments, a building that was located in the city’s prosperous Central West End, had been recently redeveloped with a $10 million TIF, and boasted “a rooftop saltwater pool, electric car charging stations, easy access garage parking, 24-[hour] concierge service, breathtaking city views, wi-fi thermostats, and customized closets.” Today the building’s website (the one they use to attract tenants, not the one they used to demonstrate the ways in which they were addressing blight), also boasts that nearby are “a Whole Foods Market and shopping plaza… Forest Park, St. Louis’ biggest and most active park—home to the St. Louis Zoo, the Muny Amphitheatre, St. Louis Science Center, History Museum, Art Museum, World’s Fair Pavilion, and… unique dining, entertainment, and nightlife in the bustling Maryland Plaza.”36

Unsurprisingly, given the readily available evidence, TIFs have come to be seen by many as both inequitable and ineffective. A 2017 study by the Show-Me Institute estimated that around 80 percent of the roughly $700 million of TIF spending in the city of St. Louis over the past fifteen years had been spent south of Delmar Avenue, the city’s long-standing racial dividing line. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch recently reported that, combined with other forms of tax abatement, TIFs cost the St. Louis city schools $31 million in 2018. Meanwhile, the Riverfront Times calculated, the city had forgone almost $1 million in taxes for each resident drawn to the city’s central corridor (the already prosperous area of the city where almost two-thirds of the city’s TIFs are located) over the first fifteen years of the new century.37

Of all the spot abatement done in the St. Louis metro area over the past decades, the most notorious has involved the developer Paul McKee, who has used tax increment financing to purchase hundreds of buildings on the city’s Northside. A 2018 investigation by St. Louis Public Radio found that of the 154 buildings that the developer had specifically promised to rehabilitate in his 2009 application for tax increment financing, only two had actually been rebuilt, one of them to house the headquarters of McKee’s corporation, Northside Regeneration. In the meantime, McKee had also benefited from the city’s Land Assemblage Tax Credit Program, a $47 million program of which Northside Regeneration was the near-sole beneficiary, accounting for over 90 percent of the credits issued by the city. With little more than a broken-down sign advertising a promise of a three-bed urgent care facility on the Pruitt-Igoe site, which McKee purchased from the city in 2016, Northside Regeneration represents a huge land bank, accredited by the city of St. Louis and capitalized by the continued suffering of the poor Black population of the beleaguered Northside.38

McKee, however, is little more than a convenient villain. North St. Louis, which appears to the naked eye to be abandoned by investors, is, in fact, a site of plentiful, if minimal, investment: tens of thousands of houses unfit for human habitation are repositories of small stores of speculative capital, bought up by speculators willing to hold the property until something changes. Rather than the absence of investment, many of the decaying houses along the routes that children walk to school every day represent a particular form of land-banking speculative investment in poor neighborhoods across the nation: long-game bets on development and gentrification. For the children, however, the message is the same no matter who owns the dead-eyed houses with the trees growing out the top: someone here before you had hopes, and they came to this.39

By the fall of 2018, McKee’s long game had gone on too long for even the city of St. Louis, which had allowed much of the Northside to lie fallow for almost forty years, and the city terminated its dealing with Northside Regeneration and condemned many of McKee’s Northside properties. The immediate occasion was the discovery that McKee had inflated the value of several of the pieces of property for which he had received bespoke land assemblage tax credits. But lurking in the background was the largest urban land clearance since Mill Creek Valley: the condemnation through eminent domain of ninety-seven acres of land in North St. Louis—formerly the Greater Ville—in advance of the construction of the new headquarters of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency—the agency that tracks electronic communication worldwide, including, it seems, telephone conversations between American citizens within the continental United States. The NGA, of course, is a sovereign entity, part of the US government, and so it pays even less in property taxes than Paul McKee did. As with the tax subsidies provided to private developers, the case for the NGA has been based upon the idea that it will bring jobs to St. Louis. How many of those jobs—jobs in the building trades, which are to this day almost entirely white, and jobs in electrical engineering and data analysis—will go to the residents of the Northside, who suffer from decades of disinvestment in their schools and the sort of structural unemployment that can sap the energy of even the most dedicated job-seeker, remains to be seen.

If the impoverished—“blighted”—condition of Black St. Louis has provided a legal alibi for the distribution of corporate welfare through tax abatement, some have found even more direct ways to monetize their neighbors’ poverty. Anyone who drives around St. Louis today, especially on the Northside, cannot help but be struck by the bright neon signs and welcoming storefronts of predatory lenders: Missouri Payday Loans, Planet Cash, Quik Cash, Community Quick Cash Advance and Payday Loans, ACE Cash Express, TitleMax, AAA1 Auto Title Loan, Title Loans Express, TitleBucks, and so on. Some of these firms are quite large—Quik Cash, the largest, headquartered in Overland Park, Kansas, has over one hundred stores across the state of Missouri—but the majority of lenders in the state represent companies with fewer than ten outlets. In one famous example, the members of a single suburban church in Kansas City pooled their money and started providing high-interest loans. Large or small, all of these predatory lenders make money by charging poor (and poorly banked or unbanked) people exorbitant rates of interest.40

Payday loans, which began to emerge on a large scale in St. Louis in the early 1990s, are the most familiar form of predatory lending. They work like this. Someone who needs money stops into a store and inquires at the counter. Perhaps they need $100. The clerk at the counter is friendly and informative and makes the requisite inquiries about wages. It often turns out that the loan applicant “qualifies” for an even larger loan than he or she had intended to take out, usually something just short of the amount of their biweekly paycheck. The terms of a loan for someone who makes $500 every two weeks might turn out to be something like $400 in cash at 500 percent annual interest, with payment due in two weeks, guaranteed in the form of a postdated check for $480. In two weeks’ time, the loan begins to bite. The debtor cannot pay $480 and still get through the following month, but the lender turns out to be willing to accommodate: if the borrower can pay just the $80 interest, the borrower will roll the loan over for another two weeks; and then, for another $80, another two weeks; and so on. After several such cycles, someone who borrowed $300 might have paid the company $1,200 in interest and yet still owe the entire principal of $300. State laws that limit the number of renewals are easily evaded by reissuing a new loan to cover the old loan every six cycles. A 2002 Missouri state law that capped the rate of interest at 75 percent for short-term loans mattered even less: multiplied out, a two-week loan at 75 percent interest represents an annual rate of 1,950 percent, the highest allowable rate among the forty-three states that have set limits.41

During the year 2008, 2.8 million payday loans were made by 1,275 licensed lenders in the state of Missouri. That year, QC Financial, the largest loan company in the state, alone made 400,000 loans through its 100 outlets. The population of Missouri is just over six million people. In 2015, the activist Jamala Rogers calculated that there were twice as many payday loan stores in Missouri as there were McDonald’s and Starbucks restaurants combined. The fact that payday lenders can now be found in every corner of the state (in 2006, nursing home owners in semi-rural Sikeston were found to be running an on-site payday loan company) suggests, once again, the ways in which extractive methods pioneered on the Black poor in urban areas can be generalized into practices that target poor and working-class people more generally.42

Although they have a lower annual percentage rate (APR)—generally around 270 percent in St. Louis—auto title lien loans are, if anything, even more dangerous for borrowers than payday loans. Automobiles are essential for many working-class people in cities like St. Louis that suffer from limited and unreliable public transportation, especially as one travels farther out into the county, where jobs are more plentiful. They are also the most substantial asset for many working-class and poor people, who spend much of their disposable income on rent and food. Auto lien loans thus pose an existential threat to those who enter the premises of any of the dozens of providers in the St. Louis metro area, disproportionately located in the poorer and Blacker areas of the city, where their shiny bright and welcoming appearance often contrasts jarringly with the surrounding economic devastation. In return for their auto title and a copy of the key to their car, customers receive high-interest loans that provide a bridge through acute crises but threaten to become chronic problems. In 2010, Beverly Brewer of St. Louis took out a $2,200 loan with Missouri Title Loans. Over the next two months, she made two payments of $550 apiece, knowing that if she did not, Missouri Title would declare her in default, seize her car, and resell it—no matter the payments she had already made. When she made the second payment, bringing the total amount she had paid on an initial loan of $2,200 to $1,100, she requested a statement of her account, which revealed a standing balance of $2,196.94. Her $1,100 had bought her six cents of principal.43

Although lawsuits like the one eventually brought by Brewer (who took her case against Missouri Title Loan Company all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States before settling when Missouri Title Loan agreed to forgive almost $250 million of debts it was holding) and reform at the federal level have curbed some of the abuses in the payday and title lien loan business, canny capitalist entrepreneurs have invented new ways to monetize their neighbors’ desperation. Many St. Louis payday lenders have recently started offering “small loans,” which have a term of six months at an APR of around 300 percent. For vulnerable people, the longer term increases the risk of events that will cause them to miss a payment and find themselves in default, such as a medical emergency, a job change, or a traffic ticket. Lenders of small loans often try to notify the borrower that the loan is in default, making what is known in court as a “good faith” effort but, in practice, is anything but; after tucking the loan away for a period of time, they pull it out of the drawer only to calculate the accruing interest. Then, after perhaps a year or so, they file suit against the borrower for the unpaid principal and accrued interest, a total that often dwarfs the amount of the initial loan. After she took out an initial loan of $100 in 2006, St. Louis resident Erica Hollins made one payment of $31 before ignoring several letters sent demanding payment of the rest. In 2009, Capital Solutions Investment filed suit against her, seeking payment for a loan on which they had been charging 199.7 percent; they obtained a judgment for $912.50. By 2015, Hollins was still so far behind on paying off her wildly exploding debt, which had grown to several thousand dollars, that CSI won a judgment to garnish her wages. But because the state of Missouri limits garnishment to 25 percent of total wages, Hollis’s court-ordered payment plan leaves her falling ever further behind on her loan, which accrues faster than her garnished wages can pay it off—she faces a 25 percent levy on all her lifetime earnings in service to what began as a $100 loan. In St. Louis, as the essayist and social theorist James Baldwin wrote of the United States more generally, “it is extremely expensive to be poor.”44

As in the rest of the nation, the 2008 subprime loan crisis wrought havoc in Black St. Louis, especially among homeowners who were trying to follow the infrastructure that had been built to subsidize white flight out to the suburbs. Many of the suburbs directly to the north of the city, Ferguson among them, had become majority-Black over the course of the 1990s, and quite a few of those migrants had become homeowners. Subprime loans accounted for almost half of loans made to Black home-buyers in the 1990s, and it became obvious in the aftermath of the crisis that as many as 60 percent of those buyers qualified for conventional mortgages but had been steered to more volatile (and more profitable for the banks) ones by their lenders. Around 2006 in St. Louis, the variable rate mortgages began to bite, and it became clear that banks like Countrywide had been using well-intended federal laws to entrap underinformed consumers in loans they could never pay—meanwhile, bundling those mortgages into packages and selling them on a speculative secondary market on Wall Street, where they made more money while spreading the risk of default far and wide through the economy.

When the bubble burst and the banks called the loans in, more than half the new homeowners—which is to say, the Black homeowners—in cities like Ferguson and areas of the city like Gravois Park found themselves underwater on their loans: the amount of money they owed was greater, in some cases far greater, than the value of their home. Many loans were foreclosed, and a Ferguson city council meeting in 2013—before the murder of Michael Brown and the uprising—revealed a government struggling to figure out what to do about all of the foreclosed and abandoned properties within the city limits. All told, the 2008 crisis is said to have destroyed as much as one-half of the Black wealth in the United States—wiping out, in the process, the gains made in the wake of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, which had begun the process of prying open the suburbs.45

If you take the time to look carefully, the geography of metro St. Louis, like that of most American cities—indeed prefiguring that of most American cities—looks less like a series of scattered, unrelated buildings, some rising, gleaming and new, some slowly subsiding back into the earth, than it does a series of patterned and planned subterranean relationships. The decay enables the growth, whether that growth takes the form of subsidized shopping malls or legalized loan sharks. St. Louis, a national leader in both tax diversion and predatory lending, is once again a city on the frontier of the future, this time pioneering modes of extraction and dispossession by which people who have been deprived of just about everything else—neighborhoods, jobs, education, health care, safety—can be squeezed dry. And in St. Louis there are few places that represent all of these features, all of this history concentrated into a small space, as clearly as the city of Ferguson.46

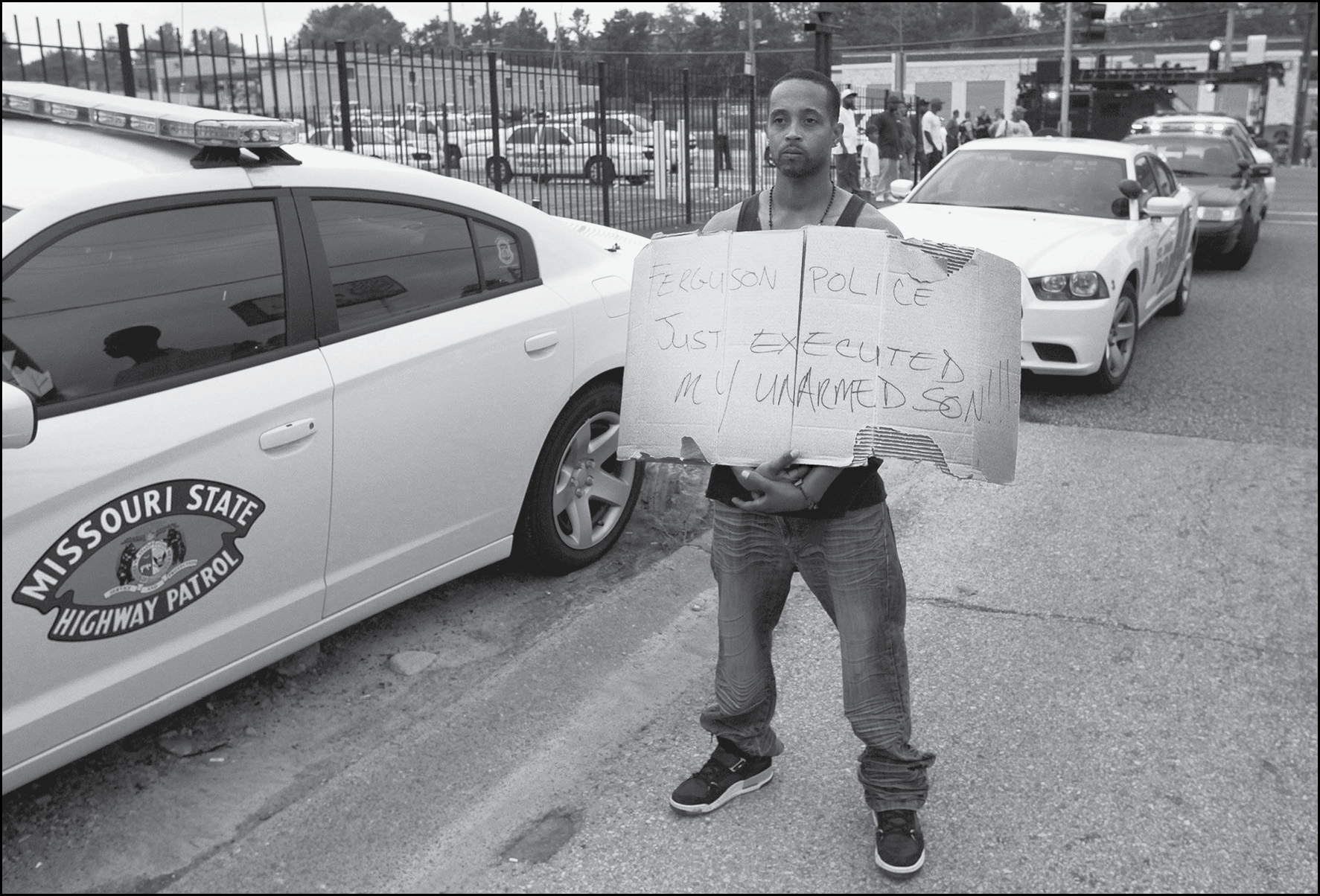

On August 5, 2014, at its headquarters on West Florissant Avenue in Ferguson, Emerson Electric announced third-quarter sales of $6.3 billion, down about 1 percent from the second quarter, but undergirded by a record backlog of orders. A quarter-mile to the northeast, four days later, Officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown, who had been walking down the middle of a street near his grandmother’s house. After a short scuffle in the street, Brown ran away. When Wilson shot him, several witnesses later asserted, Brown had his hands raised in the air. Wilson later claimed that Brown, whom he had already shot at least once, had turned around and run toward the officer, even as Wilson kept shooting. FERGUSON POLICE JUST EXECUTED MY UNARMED SON, read the placard held by Brown’s stepfather, Louis Head, as he stood near the scene. If you drew a straight line between the corporate headquarters of Emerson and Canfield Drive, less than a half-mile’s distance, it would cut through the lot behind ABC Cash Express.47

Shortly after Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson shot unarmed Michael Brown on August 9, 2014, the child’s stepfather, Louis Head, protested on the street in Ferguson. As Brown’s body lay in the street for four hours, a crowd gathered, the beginning of several months of protest and police overreaction in St. Louis that touched off a national reckoning with police violence, mass incarceration, and racial injustice that has come to be known as the Black Lives Matter movement. (Associated Press)

The protests in Ferguson transfixed the nation, providing indelible images of largely peaceful Black protesters under assault by militarized police and finally the US National Guard. The refusal that November of District Attorney Robert McCulloch (son of St. Louis police canine officer Paul McCulloch) to allow the case against Wilson to go to trial presented the nation with a lurid example of St. Louis–style police impunity. In the months that followed, anyone who cared to could have learned a lot about Ferguson. The white paper on the municipal courts in North St. Louis County prepared by the public interest lawyers ArchCity Defenders; Radley Balko’s extraordinary reporting in the Washington Post; litigation in the Missouri courts against “policing-for-profit”; and finally, the March 2015 Justice Department report on the Ferguson Police Department—all helped to fill in a picture of the extraordinary climate of police harassment that culminated in the murder of Michael Brown. In Ferguson during the year 2013, 86 percent of traffic stops involved Black motorists, in spite of the fact that the population of the city was only 67 percent Black and its roads were driven by a high number of white commuters. After being stopped, Blacks were twice as likely to be searched and twice as likely to be arrested as were whites, in spite of the fact that, when whites were searched, they proved to be two-thirds more likely to be caught with contraband. The initial citations in these cases and other similar municipal violations ranged from speeding and running red lights to driving without current registration or proof of insurance to having an unmowed lawn, putting out the trash in the wrong place at the wrong time, and jaywalking, known in the language of the Ferguson city code as improper “manner of walking in the roadway.”48

The peculiar prominence of police stops for “manner of walking in the roadway,” and the multiple occasions upon which they were followed by citations for “failure to comply,” hint at something about the everyday terrain of policing in Ferguson in the years leading up to 2014. Indeed, similar citations were common in Meacham Park during the same period. “There were a couple of our kids that got tickets for walking in the streets,” remembered one resident of Meacham Park. “We never had sidewalks around here until [we were] annexed, so a lot of people, especially the older people and like young people, they never walked on sidewalks, so it took a minute to adjust. But the officers were giving people tickets for walking in the street, not just warnings, but they were giving them tickets.” Another resident remembered a similar set of public order offenses being extended over an empty lot where the men of Meacham Park had long gathered to socialize. Growing up, he said, “I aspired to get a job and retire and be able to pull my truck and my car up on the lot and be able to sit with the old men and drink my drink and sit by the fire. Grown men. Family men.… That’s history, but the police and Kirkwood look at it as hanging out in the streets.” And then there was Cookie Thornton, parking his truck where he had always parked it, hanging his sign the way he had always hung it, doing business the way he had always done it, but finding himself suddenly on the wrong side of the law.49

Code violations are characteristic offenses of the racial capitalism of the real estate market. In Meacham Park, they took the form of the policing of the neighborhood’s erstwhile common spaces—roadways and lots that had served social purposes but were now subject to new value-protecting standards. In Ferguson, the social history was different, but the pattern of policing was similar: in 2012, the city of Ferguson issued two thousand tickets for property maintenance code violations. Like most of the rest of St. Louis County (including “Kirkwood proper”), mid-twentieth-century Ferguson had been defended by exclusionary zoning codes and whites-only collusion in the real estate market. In the 1960s, Ferguson was known as a “sun-down” community: African Americans, mostly from neighboring Kinloch, came to work in the houses of wealthy whites in Ferguson during the day but were expected to be out of town by the time the sun set—an arrangement that was underscored by the effort of a large number of Ferguson residents to build a wall between the two cities in the mid-1970s. To this day, the adjacent cities are joined by only two through streets. If you have ever flown into the St. Louis airport, you have seen Kinloch up close. Over the past three decades, the vast majority of that city’s Black residents have been displaced to accommodate the expansion of Lambert–Saint Louis Airport. Over the same period, a small number of African American homeowners and a much larger number of African American renters have gradually replaced whites in Ferguson. Almost entirely white in 1970, Ferguson today is majority-Black.50

An entire book could be written about the sensory aspects of white public order as enforced in St. Louis, whether the social setting is one of annexation (as in Kirkwood), Black migration (as in Ferguson), or gentrification (as in St. Louis neighborhoods like Benton Park, Botanical Heights, Tower Grove, and Shaw, where VonDerrit Myers Jr. was shot on October 8, 2014, by a St. Louis police officer who was detailing for a neighborhood watch group). Indeed, the political scientist Andrea Boyles’s book about Kirkwood provides a brilliant exemplar of such a study. She details the ways in which the sounds of men drinking and boasting on an abandoned lot came to seem threatening; or kids standing together and talking on a corner came to seem suspicious; or braids and baggy pants and grills and tattoos came to be seen as signs of criminality rather than as the basic signs of accumulation available to people who don’t own much other than themselves. “A lot of these boys that just be standing around are the sweetest boys if you knew them personally,” Boyles quotes one Meacham Park resident as saying, “but in the police’s eyes, it’s like they are trying to stir up trouble.” Rather than the advancing frontier of whiteness, as in Kirkwood or in any number of gentrifying neighborhoods across St. Louis or the United States where the police serve as public-order adjutants for the protection of white settler sensibilities and rising property values, in Ferguson the policing of public order represented a rearguard action taken on behalf of a declining white population by an almost entirely white city government.51

In some ways, Ferguson’s pattern of racist policing is reminiscent of the “predictive” policing pioneered in St. Louis in the late 1960s and early 1970s. But where the random data-collecting stops on the Northside were framed by a logic of preemption—a theory that treated every young black man as a potential low-level offender and every low-level offender as a potential felon—policing in Ferguson (and many neighboring municipalities) seems to have been as focused on extracting revenue from an already impoverished community as it was on preventing hypothetical future crimes. “Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs,” the Justice Department concluded in its report on Ferguson’s police department. The report found that the boundary between the fiscal and police functions of the city government of Ferguson had completely broken down. The city manager and the police chief had discussed using tickets to meet revenue benchmarks, and police officers were being evaluated on the basis of their ticket-pushing “productivity.”52

In 2013, the city of Ferguson earned $2,635,400 from municipal court fines, which accounted for 20 percent of the city budget—the second-largest revenue share drawn from any single revenue source. “Absolutely, they don’t want nothing but your money,” the ArchCity Defenders’ white paper quotes one defendant as saying. “It is ridiculous how these small municipalities make their lifeline off the blood of the people,” said another. “It’s an ordinance made up for them,” said still another. “It’s not a law. It’s an ordinance.” Following upon the initial citations from the years before 2014, the city issued over twelve thousand warrants for missed court appearances and unpaid fines. Citizens who failed to appear in court at the appointed time or to pay fines that were, according to the ArchCity Defenders, “sometime more than three times a person’s monthly income,” were liable to be jailed, sometimes for as much as three weeks, as they awaited a municipal court date. Those with outstanding warrants were likewise rendered ineligible for most forms of public assistance and government-provided social services.53

The city of Ferguson—with its white mayor, its majority-white city council, its almost totally white police force, and its white municipal court judge—was farming its poor and working-class black population for revenue. Cantoned according to the laws and practices of a white supremacist real estate market, the black inhabitants of Ferguson were summoned for a final round of extraction that threatened in many cases to dispossess them entirely, as excessive fines, exclusion from necessary social services, and exclusion from public housing combine to turn them out onto the streets. The murder of the jaywalking Michael Brown was an acute example of the chronic exploitation, harassment, debt bondage, and wanton bankrupting of the city of Ferguson’s African American population.

In this, again, Ferguson is a pertinent example of the arc of our times. Over the past fifty years or so in the United States, discriminatory policing, selective enforcement, disparate rates of conviction, and wide variations in sentencing by race have combined to create a vast class of incarcerated and disenfranchised Black men. While African Americans account for 14 percent of the drug users in the United States, they yield up 35 percent of those arrested, 53 percent of those convicted, and 45 percent of those imprisoned for drug crimes. Where many see mass incarceration as a form of racial control—a “new Jim Crow”—Ruth Wilson Gilmore has importantly pointed to the role of prisons in creating and perpetuating opportunities for the accumulation of white wealth. The construction, maintenance, provision, and supervision of the vast US inland empire of incarceration has underwritten the economic development of entire communities—rural towns now compete to have prisons sited within their corporate limits—and the emergence of a new segment of the white middle class. In the post-industrial United States, the political economy of racial control is an emergent sector. Of the twenty-two state correctional facilities in Missouri, nineteen have been built since 1980, a period during which the state’s prison population has increased by over 300 percent (to 859 per 10,000, well above the national average). Although the inmates in Missouri prisons are over four times as likely to be Black as white, almost all of the facilities are located in predominantly white rural areas—places such as Licking, Vandalia, Bowling Green, and Potosi—where they employ predominantly white construction workers, guards, and service workers and are often the leading sector of the local economy. The generalization of the economy of mass incarceration to a principle of municipal governance is evident in police practice in Ferguson.54

The Justice Department’s Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department traced the revenue-farming in Ferguson back to a lack of training, supervision, and oversight, exacerbated by shoddy record-keeping and clear racial bias. The DoJ’s report on the Ferguson police is almost unprecedented in its critical attention to systematically racist police practice in the United States. As such, it took what had long been the common sense about policing among poor and African American people across the country and briefly raised it to a principle of federal public policy. But the report stopped short of providing a structural analysis of racist policing in Ferguson. Put simply: how could the city government be reverting to medieval modes of revenue extraction at the same time that Emerson Electric was doing $24 billion a year of business out of its Ferguson headquarters? In Ferguson, the answer lay in the historical amalgam of white privilege, corporate welfare, fiscal conservatism, and misguided efforts to promote social equality through “economic development,” which had guided municipal policy since the 1980s. Again, Ferguson, St. Louis, and Missouri are not unique in this so much as they are extreme: they provide an exemplary account of how state and local governments think about “economic development” and how corporations do business in the United States of America today.55

Take Emerson Electric. On July 27, 2009, Emerson opened a new $50 million flagship data center on its Ferguson campus. Subsequent press reports about the data center were filled with numbers: 100 dignitaries at the ribbon-cutting, including Missouri governor Jay Nixon; 35,000 square feet; 550 solar panels; $100,000 in annual energy savings for the company; ability to withstand an 8.0 magnitude earthquake. They noted how many people Emerson employed globally, nationally, and in the St. Louis metropolitan area, although the number of people who might eventually be employed in the new data center itself was hard to determine. In fact, a state-of-the-art data center might eventually employ about two dozen people, none of whom were guaranteed to live in (or anywhere near) Ferguson. The economic function of a data center, after all, is to eliminate clerical workers, not to provide them with jobs, and many of its operations can be performed remotely. But the most remarkable missing number of all was the amount of property tax revenue the county and city housing this state-of-the-art building would gain from its construction.56