The Spartans Voted to fight in autumn 432 but waited to begin hostilities for some six months. During this phony war, their agrarian allies the Thebans first attacked the small town of Plataea even as various envoys shuttled between Athens and Sparta. But once spring came and the favorable conditions for traditional invasion arrived, thousands of Spartans realized that they had to either move or apologize for the reckless preemptive act of their Theban ally.

The Spartan idea was to marshal the Peloponnesian League, invade Attica, destroy farmland, and hope that the Athenians came out to fight. Barring that, the strategy fell back on the hope that food lost at harvesttime would cause costly shortages at Athens and that the humbling presence of Spartans near the walls of the great imperial city would encourage its restless subjects to revolt. And barring that, the Spartans could at least say they were in Attica and the Athenians were not in Laconia.

But the hide of permanent plants is tougher than men’s. Orchards and vineyards are more difficult to fell than people, as the Peloponnesians quickly learned when they crossed into Attica in late May 431. Attica possessed more individual olive trees and grapevines than classical Greece did inhabitants. Anywhere from five to ten million olive trees and even more vines dotted the one-thousand-square-mile landscape. The city’s thousands of acres of Attic grain fields were augmented by far more farmland throughout the Aegean, southern Russia, and Asia Minor, whose harvests were only a few weeks’ sea transport away from Athens. What, then, were the Spartans thinking?

Partly in pursuit of that answer, a few years ago I tried to chop down several old walnut trees on my farm. Even when the ax did not break, it sometimes took me hours to fell an individual tree. Subsequent trials with orange, plum, peach, olive, and apricot trunks were not much easier. Even after I’d chainsawed an entire plum grove during the spring, within a month or so large suckers shot out from the stumps. Had one wished to restore the orchard, new cultivars could have been grafted to the fresh wild shoots. Apricot, peach, almond, and persimmon trees proved as tough. Olives were the hardest of all to uproot. It was even more difficult to try to set them afire. Living fruit trees (like vines) will not easily burn—or at least stay lit long and hot enough to kill the tree. Even when I ignited the surrounding dry brush, the leaves were scorched, the bark blackened, but no lasting damage was done.

Thucydides observes that the Spartans, during their fourth invasion of Attica in 427, needed to recut those trees and vines “that had grown up again” after their first devastations a few years earlier—a phenomenon of regeneration well recorded elsewhere of other such attacks on agriculture. It was difficult enough to bring an army into Attica, but harder still to accept that its destructive work needed redoing within four years. Someone who attempts any of these tasks of destruction—even without enemy horsemen loose on the counterattack—soon understands that when an ancient Greek author formulaically described troops as “ravaging the land” (dêountes/temnontes tên gên), he probably really meant something like “they attacked, but could not easily destroy the land.”1

But wait: did not the Greeks live on bread, not just wine and oil, and thus in fact were not the Spartans easily torching all the city’s critical grain that they did not consume on the spot? After all, burning a ripening grain crop for the Spartans in Attica should have been far easier than chopping trees or vines. Gazing out at thousands of acres of swaying dry wheat stalks, one might think that a single ember could make the entire task ridiculously easy. But even igniting grain is not always so easy, for a variety of reasons. If one ignites a dry barley field, in place of the expected sudden inferno, the small fire sometimes burns only a little before the flames quietly go out. The stalks are often greener than they look—and spaced farther apart than what meets the eye.

When and how one burned a field seemed to make the difference between conflagration and sporadic fires. Other factors involved atmospheric conditions and the stage of maturity and the moisture content of the grain fields. The same is true of burning permanent crops of trees and vines. Exasperated growers today sometimes rent five-hundred-gallon propane flamethrowers to guarantee that their brush piles will not go out prematurely. And even seemingly dry piles of dead fruit trees are sometimes impossible to ignite.

Even when one is not wearing armor or dodging arrows and javelins, the art of agricultural combustion is a tricky business. Therein lay one of the many paradoxes of traditional Greek land warfare in the decades before the Peloponnesian War: the tactic was just as frequently predicated on anticipated, rather than real, damage. Trees and vines, after all, are permanent crops, whose damage does not entail merely the loss of a yearly crop but rather the investment of a lifetime, with clear psychological implications to touchy farmers in harm’s way.

This paranoia of the property-owning—and especially tree- and vine-owning—agrarian is what prompted an anonymous contemporary Athenian reactionary to note, “Those who are farming and the wealthy among the Athenians are more likely to reach out to the enemy, while the commons know that nothing of their own will be burnt or cut down, and so live without fear and don’t ingratiate themselves with the enemy.”2 The comic playwright Aristophanes also remarked on the strange patriotic calculus that arose in a fortified Athens: the most prominent stewards of a state’s hallowed soil—hoplite infantrymen—were the most likely to avoid conflict, while the shiftless poor were more eager to fight its country’s enemies.

In an agricultural landscape, ravaging crops was an affront to the spiritual and religious life of the polis, besides a potential threat to its economic livelihood. Of course, if a state was landlocked and unwalled, if a community was caught napping, and if the enemy came at precisely the right time, an entire grain harvest might be torched with not much effort. Such a loss surely could bring on near and immediate starvation—and on occasion it did. Yet more often in the ancient world that near-perfect scenario would require too many ifs. Thus, neither Spartans in Attica nor Athenians in Sicily ever completely destroyed the agricultural landscape of their adversaries.3

Man’s creation of cement and steel for roads and factories possesses none of the beauty or the age or the mystique of the olive among Mediterranean peoples. That the olive is an evergreen tree in a hot climate; that it possesses enormous powers of regeneration; that it can grow almost anywhere without constant attention or great amounts of water and fertilizer; that it reaches great age; that its fruits provide everything from fuel to cooking oil to food—all that combines to surround the tree with a nearly religious awe to match its undeniable utility, both now and in the past. That majesty explains why myths surrounded the supposedly indestructible olive growing on the Acropolis and why drama praised the tree as symbolic of Attica itself. The olive tree, in other words, was a fat target, full of symbolic capital.

Hoplite infantrymen outside Sparta were originally mostly farmers—and, like most other ancient Greek citizens, proud of it; as Aristophanes reminds us, “The farmers do the work, no one else.”4 In a preindustrial world in which it often required nine people to farm to support ten, agriculture was the linchpin of all social, economic, and cultural life. Working the soil defined a man’s spiritual existence, from the cultivation of ancestral trees and orchards to the stewardship of revered rural shrines and the preservation of his father’s home, which he wished to pass on to his son.

Despite the images of the majestic Parthenon, the sophisticated symposia of Athens, or the crack phalanx of professional Spartan killers, most Greeks were nevertheless food producers. Thus, in multifaceted ways the war was conditioned on precisely that fact. Agriculture is the real landscape of the Peloponnesian War, the source of the food that would fuel the combatants, the home to most of the participants, and indeed often the very locus of the fighting itself.

The rural Greeks were not quite animists who believed that their trees and animals were divine spirits. Yet they accepted that their countryside was alive with lesser deities who protected rivers, springs, trees, and shrines. Such mystical immanence was one reason why agriculture was more than just the art of producing food. The Athenian philosopher, historian, and warrior Xenophon summed up “the best life” as one of farming, which gave man “the greatest degree of strength and beauty.” In moral and practical terms, agriculture made “those who work the soil brave, the best citizens, most loyal to the polis.” When soldiers evacuated their farms, their anguish arose not merely from the fear of economic losses; rather, the provocation was intended to be as much a matter of wounded pride and generational shame as material damage.5

When Aristophanes’ characters are portrayed as bottled up in Athens during the Spartan invasions, they sigh that they wish to return to their ancestral farms, see individual trees and vines they have planted, and visit sacred shrines. These scenes were not fantasy creations of a comic poet. During the evacuation Aristophanes had grown familiar with the lives of some of the 20,000 Attic farmers who owned and farmed much of the 200,000 acres that surrounded Athens. They were the doughty rustics who formed the nucleus of the traditional army that in the fifth century alone had beaten the Persians at Marathon, crushed the feared Boeotians at the battle of Oinophyta, and fought shoulder to shoulder alongside the Spartans at Plataea and in Messenia. The best way to prompt these “most loyal” men of an agrarian militia to come out and fight was to assault these symbols of what it meant to be a free landowning citizen—and there were still thousands of these stout farmer-citizens even in 431 in a maritime and imperial Athens.

Whatever the impracticality of the Spartan strategy, King Archidamus and his generals at least realized the spiritual stakes involved. The major Athenian playwrights—Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes—all at one time or another either boasted about the sanctity of Attica or lamented its suffering from enemy devastators.6 Their anguish during the war reflected a long Greek tradition: during most intramural Greek land warfare between 700 and 450, the sight of a few ancestral olive trees hacked by an ax was enough to draw the angry hoplites who owned them into battle. Wars between property owners can start over perceived rather than real grievances, over a few scarred trunks rather than thousands of acres of obliterated orchards. When a modern visitor examines the scrub and maquis on the rocky borders between Attica and Boeotia or Argos and Sparta, he might wonder why such sophisticated societies started a war over the ownership of such seemingly worthless ground.

The reactionary Spartans were not completely unhinged, then, when on arrival in Attica in late spring 431 they thought that the Athenians would march out in suicidal fashion and form in the phalanx once they experienced fire and sword. True, the Spartan phalanx itself instilled terror and seemingly would have scared off any potential adversaries. But in nearly 75 percent of the cases of hoplite battle, defending Greek armies defeated the invaders and thus were confident in a home-field advantage—so strong was the psychological edge for property owners when defending their own sacred soil.

So accepted a tactic had ravaging become that it was institutionalized in the clauses of farm leases and peace treaties. Devastation of farmland was deeply ingrained in the popular culture, and a general staple of ethical discussion. Catchphrases amplified this almost annual experience of attacking permanent crops, in the form of boasts to make “cicadas sing from the ground” or threats “to turn cropland into a sheep walk” if demands were not met.7 Much of the logic of war, in other words, had been static for centuries in a rural society of unfortified hamlets. Apparently very few in the Peloponnese realized that all the rules were about to disappear as Greece was on the eve of the first true military revolution in the history of Western civilization.

Only a quasi police state that had no real money, no walls, no lively intellectual life, no notion of upward mobility, and no immigration could naively assume that a parochial tactic that worked with wayward rural neighbors of the Peloponnese could bring down the greatest state in the history of Hellenic civilization. It was even worse than that: throughout the fifth century Athens had constructed the most massive municipal fortifications in the Greek world precisely to guarantee supplies of imported staples and in part to create immunity from agrarian warfare. In one of the most understated passages in Thucydides’ history, the Corinthians remonstrate with their Spartan allies, saying, “Your methods, compared to those of the Athenians’, are old-fashioned.”8

In reality, most of the conservative Greeks also shared the Spartan naïveté—that it would be a win-win situation for the invaders. Surely they would either kill Athenian soldiers or starve out their families. Before the Spartans and their allies actually reached Attica, Thucydides, for example, wrote that they had supposed that they could defeat Athens “in a few years should they ravage its territory.” Neutral observers had agreed about the cheery prognosis: “If the Spartans should invade Attica, some thought that the Athenians could hold out for a year; others two; but no one longer than three years.” Thucydides does not tell us who those “some” were; they were probably his oligarchic Athenian friends and aristocratic sources in Sparta who—unlike the historian himself—never quite grasped the revolutionary nature and resiliency of a radically democratic Athens. It was only later and after a long decade into the war that the Spartan general Brasidas reflected on how wrong such old and simplistic ideas were. He admitted such to his troops in the field years after the outbreak of the war: “We were wrong in the idea we had of war back then, when we thought that we would be able quickly to destroy the Athenians.”9

Forgetting the earlier evacuation and abandonment of the Attic countryside before the massive invasion of Xerxes’ Persians in September 480, most Spartans instead were wedded to the idea that the Athenians would react as they had a decade earlier to Darius’ initial landing at Marathon in 490, some twenty-six miles northeast of the city. During that first Persian invasion of Greece, thousands of Athenian farmers donned their armor and rushed out to protect the soil and prestige of Athens—winning lasting fame as the “Marathon battlers” who had saved the city in a single stroke.

The invaders also drew confidence from a more recent example: fifteen years earlier, when faced with the Spartan invasion of 446 during the First Peloponnesian War, the Athenians had seen a Spartan king and his army turn around right at the border, thus providing an eleventh-hour reprieve for both their troops and their farms.10 Accordingly, in May 431, older Athenians had good reason to think that the Spartans might once more be cajoled or bought off to make a ceremonial demonstration of force before withdrawing as they had before. On the eve of the war, the edgy Corinthians confidently urged the Spartans to invade “without delay.”11

The campaign was envisioned by the Spartans themselves as one of a season or two: burn some grain and cut down some vines and trees, wait for 10,000 Attic farmers to pour out to battle, and witness the professional infantrymen of Sparta, supported by thousands of other allies, make short work of them. After all, sixteen years earlier the Boeotians had expelled the Athenians from their homeland and ended their war outright through a single devastating defeat of the Athenian army at the battle of Coronea (447). No one expected the Athenian defenders to fight quite like the Boeotians had at Coronea, but many thought they would at least fight.

Athenian allies in the Aegean would become emboldened by the sheer audacity of Spartan troops near the walls of Athens and quickly revolt. The city would then sue for peace. Sparta would dictate terms: perhaps freedom for Greek subjects to leave the Athenian empire and guarantees of neutrality for “Third World” states. Further Athenian concessions would be made: surrender of border forts, reduction of the fleet, or alliance with Sparta. Everyone could pretty much go back home with the issues of prestige, honor, and status clearly resolved on the battlefield. A few Greeks might have appreciated Spartan past efforts to depose Athenian tyranny and the bravery of the Spartan army fifty years earlier at the battle of Plataea, when it stopped the Persians cold, and thus found its surprising present posture as the liberator of the city-states from Athens somewhat credible.

This inflexible strategy was the first of a chain of tragic miscalculations, as even the commander of the Peloponnesian invading forces at last realized before the march began. “The Athenians have plenty of other land in their empire, and can import what they want by sea,” the Spartan king Archidamus warned in a Lord Grey—type “the lamps are going out” speech. He added ominously, “Let us not be caught up in the hope that the war will be over if we just ravage their countryside. I fear instead that we shall leave war as a legacy to our children, so unlikely it is that the Athenians will prove slaves to their land or like amateurs they will become shocked by the war.”12

The Athenians at the very outset realized, albeit accidentally, that the only way they would lose the war would be when an enemy accomplished what Lysander eventually pulled off twenty-seven years later, when he sailed into the Piraeus and finally sat atop the Acropolis. The Athenians made an arrangement to set aside the enormous sum of 1,000 talents—in today’s dollars about $480 million—in an emergency reserve defense fund to draft more troops and build more ships in case the Spartans sent a fleet against the Piraeus. In fact, in 429 the frustrated Spartans attempted just such an incursion, and their daring maritime attackers nearly succeeded in getting close to the harbor before being driven off from Salamis and back to Corinth.13

As a popular leader of a radically democratic state, Pericles realized that perhaps a quarter of his voters—his core poorer constituents—owned little or no land. Half the citizens of Athens rowed in the fleet or worked in his program of public works to create his majestic imperial city. As the indignant philosophers and elites complained, the poorer thetes would not personally suffer directly from an attack on farmland that they did not own.* Many urban dwellers knew very few Attic farmers. Perhaps they rarely even saw them in town. Instead, they could profit greatly as paid rowers to patrol and to protect the sea-lanes. Out of that domestic self-interested political calculus of sacrificing native agriculture also arose the best way collectively to defend the maritime empire of Athens.

Yet Pericles was not merely cynical or eager in wartime to divide his own people along political lines. He also grasped two other essential shortcomings about Spartan strategy on the eve of the first invasion of 431. First, it was not an easy task for tens of thousands of parochial folk to leave their own harvests, march from over 150 miles distant, live off the land in transit, and systematically destroy in a few days some 200,000 acres—especially when Athenian rural garrisons and cavalry patrols made invaders in small groups and out of formation easy prey. Later the Athenians believed that if they could just knock the Boeotians, who provided cavalry support for the ravagers from the Peloponnese, out of the war, the invasions would cease altogether. Horsemen apparently fought horsemen to keep the Athenian cavalry from riding down vulnerable ravagers.

The Spartans also came in such numbers that their army seemed too formidable to achieve its aim of prompting battle, and likewise almost too large to feed.14 Just to supply so many thousands while in Attica was a logistical nightmare and was predicated entirely on how quickly they could get to Athenian grain while it was ripe and either unharvested in the field or not yet transported into Athens. Modern studies have suggested that during the five invasions the Peloponnesians would have consumed in aggregate grain equal to an entire annual Attic wheat and barley harvest. By June 431 there may have been altogether almost 400,000 Peloponnesians and Athenians either out in the Attic countryside or inside the walls of Athens—a vast, mostly nameless mob of desperate folk at war that warrants almost no mention in our ancient sources.15

Pericles had warned about the perils of facing the national army of the Peloponnesians: even had the Athenians won a single pitched battle against such enormous numbers of hoplites, such a dramatic victory still would not have decided the war. To meet such an army in pitched battle was a “terrible thing” to contemplate, in which even a miraculous victory might have little strategic effect. It is difficult to know whether Pericles feared the sheer size of the Peloponnesian allied army or the presence of Spartans themselves, who probably made up only 10 percent of the aggregate force, or some 4,000 to 6,000 hoplites. Later, in 406, King Agis brought an army of almost 30,000 troops right to the walls of Athens. But the Spartans marched only on a moonless night, and were not willing to fight a battle within bowshot of the city. In turn, the Athenian phalanx had no desire to meet them distant from the protective support of archers on the ramparts.16

As Spartans tried to cut down olive trees in Attica, Athenian marines and light-armed troops, albeit in far fewer numbers, could be ferried to the coastal towns of the Peloponnese to harass through raiding and plundering. Such tactics had been used years before in early battles between Sparta and Athens. In fact, for the first decade of the war, the Athenians conducted raids all over the Peloponnese. They stormed small hamlets where the grain harvests were collected and vulnerable. Pericles’ raiders achieved such terror and disruption that a popular tale circulated that the Athenians had done more agricultural damage in the Peloponnese than the Peloponnesians had in Attica.17 It was just such a ravaging expedition much later against the seaboard of Laconia in summer 414 that outraged the Spartans enough to cause them to renew the war. They claimed that such audacity in attacking their sacred soil at a time of reconciliation was an insult to their pride, thus prompting them formally to annul the provisions of the Peace of Nicias and at last restart full-scale hostilities against Athens.18

Very soon the Athenians would exploit the helot paranoia of Sparta. If the Spartans’ own Peloponnesian agrarian allies had harvest concerns that limited the amount of time they could be away from their crops, the Spartans worried not about unattended fields but rather about unattended field-workers. They fretted constantly that nearby peoples like the Argives or Arcadians were just waiting to promote helot rebellion to facilitate their own aspirations for independence.19

For all these reasons, the Athenian leadership had convinced everybody except the farmers themselves that the Spartans would not seriously damage the heartland of Athens—and most certainly not force the Athenian state to either come out to fight or capitulate. Even the rebellious maritime subjects of Athens, who in the past had believed that invading Attica might allow them to revolt from a distracted Athens, finally came to agree. In seeking Spartan support for their revolt of 427, after four Spartan invasions, the Mytileneans of Lesbos at last shrugged, saying that the “war will not be won in Attica” but waged and won on the seas rather than by burning and cutting crops.20

Such visions of a naval victory took two decades to evolve at Sparta. In the meantime, the key, Pericles realized, to beating these Dorian reactionaries was to keep everyone inside the walls—no easy task with thousands of hotheaded Attic farmers. He must in addition guarantee that the trade routes were safe and the Athenian triremes vigilant for signs of maritime rebellion. Later, ambivalent states in the Peloponnese like Argos and Mantinea might come over to the Athenian side, and so surround Sparta with nearby enemies. Boeotia, as had happened between 457 and 447, might also be invaded and once more be made a democratic ally.

But all that was in the future. For now, in the spring of 431, Pericles had the more immediate problem of dealing with a 60,000-man enemy army on the horizon. So he reminded his citizens that trees and vines—unlike men—could regenerate when cut down. He announced to his grumbling compatriots, “If I thought I could persuade you, I would have you go out and waste them with your own hands.”21

But, of course, he could never convince such yeomen of Attica. A few months before Archidamus arrived, the Athenians watched Euripides’ Medea, a play in which their countryside was praised as “the holy land that is un-wasted”—a reflection of how comforting that boast was to most Athenians. Indeed, there is a special word in the Greek language, aporthêtos (“unplundered”), that reflects this almost religious pride in land that has been untouched by the enemy due to the courage and strength of its hoplite citizenry. In this context, did the Spartan failure in Attica between 431 and 425 to win the war or concessions prove that the strategy of agricultural devastation was no longer of much value in a conflict as multifaceted and long as the Peloponnesian War?

Not quite. Later in the war, the reactionary practice of ravaging still continued to spark resistance, internal strife, capitulation, or hunger at places like Corcyra, Acanthus, Mende, and Melos. But then, unlike the exceptional case of Athens, none of those places had extensive fortifications connected to a well-protected port, reserve capital, secure supplies of imported food, an empire and fleet, and a relatively united democratic population.22 In addition, Greeks would come to appreciate devastation as a tactic of economic warfare in its own right, rather than a catalyst to pitched battle.

If King Archidamus and his Peloponnesian army completely underestimated the problems of ravaging Attica and the nature of Athenian countermeasures, Pericles himself also failed to grasp three fatal flaws in his own otherwise cogent strategy of attrition. First, he assumed that a city built for 100,000 urban residents might accommodate—without problems of housing, water, and sanitation in the Mediterranean heat of late spring and summer—an additional population of some 100,000 to 150,000 rural refugees for a month or more. He was in error. Thousands of refugees would be without permanent shelter. They would quickly overtax the fountains, latrines, and sewers of the city. And the evacuees would grow angry at having been forced to leave their homes, and soon become uncomfortable with city folks—most of whom they had never seen before and probably did not like.

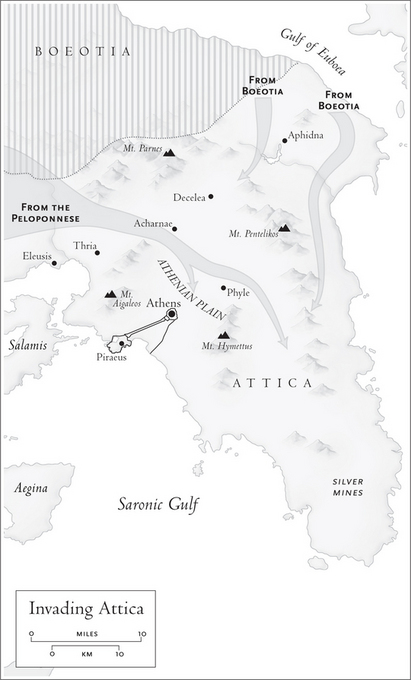

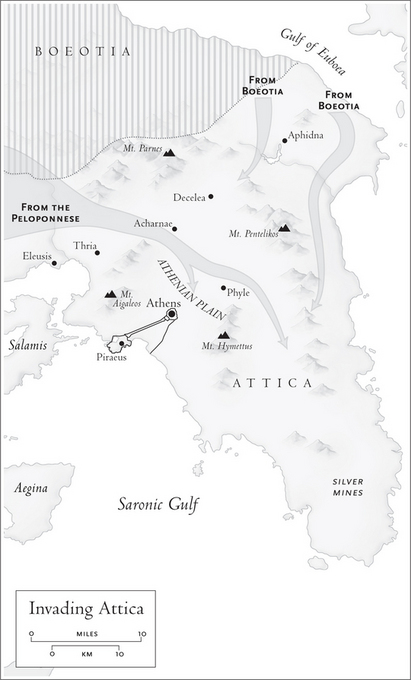

Pericles planned to turn the most majestic city of the Greek world into one enormous and squalid refugee camp in an age before knowledge and proper treatment of microbes—a radical policy that had been attempted during neither the Persian nor the First Peloponnesian War. Anyone who has spent summers in modern Athens can appreciate the afternoon heat that descends on the city and the air that grows stagnant—lying as it does in a basin surrounded and cut off by the ranges of Mounts Aigaleos, Parnes, Pentelikos, and Hymettus and without either a major river or the seashore in its immediate environs.23

Later a tired Pericles himself confessed to a worn-out and angry assembly, “The plague was the one event that proved greater than our foresight.” There is more tragic irony here: the earlier construction of the Long Walls (461–456) was in line with Themistocles’ notion of ensuring that in the future Athenians could avoid pitched battle, stay in the city, and thus not have to flee en masse to the nearby islands. In fact, that earlier traumatic evacuation of Athens in 480, by dispersing the population among nearby Aegina, Salamis, and Troezen, mitigated the chances of overcrowding and plague. What Pericles needed perhaps was not so much a military strategist as a public health expert. Meanwhile, he appeared as foolish as Archidamus did wise. A chance pestilence proved the strategic insight of the former disastrous—and the banal ideas of the latter inspired.24

Second, Pericles gambled that the Athenians—a people that had once marched out to Marathon to beat an army three times its size and had sunk a numerically superior Persian fleet at Salamis in sight of the Acropolis—could now sit idly by without damage to their national psyche while thousands of enemies swaggered in to challenge their martial prowess. Of course, farmers would soon grow irate that their homes were overrun. But the collective population at large would also have to stomach the even more odious idea that none of their men would dare to fight an enemy a few miles from the walls.

War is never merely a struggle over concrete things. Instead, as great generals from the Theban Epaminondas to Napoleon saw, it remains a contest of wills, of mentalities and perceptions that lie at the heart of all military exegeses, explaining, for example, why a Russian army that collapsed in 1917 on its frontier held out in its overrun interior during World War II, or how a completely outnumbered and poorly supplied Israeli army between 1947 and 1967 overwhelmed enemies that enjoyed superior weaponry and a tenfold advantage in military manpower.

So once the Athenians had established the precedent that enemies could occupy their homeland with the near assurance that they would not or could not be forcibly removed, would not an inevitable sense of collective self-doubt and insecurity follow? Again, would other enemies—or Athens’ own critical and large Aegean subject states, such as Chios, Mytilene, and Samos—feel that Athens either could not or would not any longer respond to attack? How exactly could a proud empire prevent insurrection on distant island subject states, when it would not even defend its own soil? Most potentially rebellious Greeks were not versed in tactical nuances and thus did the simpler moral arithmetic in terms something like “Did our masters, the Athenians, fight or in fear stay behind the walls?”

Years later, on the eve of the Sicilian expedition, one of the arguments that the sophist Alcibiades used to convince the Athenians—a citizenry that had lost a quarter of its population to the plague and had its land occupied on five occasions—to attack Syracuse was that by nature Athens was suited only to aggressive strategies and would cease to exist if it opted for a passive posture. Perhaps one reason why Alcibiades’ often fallacious logic struck a chord was that the hotheads in his audience could recall Archidamus’ early invasions—when the Athenians had stayed still, and such passivity had brought them the plague, the death of Pericles, and no clear-cut advantage for ten years.

Ultimately, if Athens entered a conflict against the greatest land power in the Greek world, it had to destroy either the Spartan army or the system—the entire foundations of helotage—that allowed such a professional military to train and march abroad. There is little indication that Pericles, at least at the outset, ever envisioned such bold offensive strokes as organizing a Panhellenic coalition to descend into Laconia, or even a way to pay for the fighting if it went beyond five years. Again, wars do not really end until the conditions that started them—a bellicose government, an aggressive leader, a national policy of brinkmanship—are eliminated. Otherwise there remains a bellum interruptum, much like the so-called Peace of Nicias, when Athens and Sparta agreed to a time-out in 421, before going at each other with renewed and deadly fury in 415.

Third, Pericles assumed that a leader of his rhetorical talents, political experience, and moral authority could rein in both conservative farmers and democratic extremists and do so systematically and steadily until the Spartans gave up. His surviving busts in stone, like those of a similar war leader, Lincoln, appear almost serene. His hoplite helmet is pushed to the back of his ample forehead, a visage reflecting concern with monumental issues, while indicating neither arrogance nor insecurity.

For over thirty years, Pericles as the most important statesman at Athens had exercised just such Olympian moral clout, and thereby lent a sense of political consistency and continuity unusual for an ancient democracy that functioned without constitutional checks and balances on the majority votes of a fickle assembly. His savvy mix of radically egalitarian sympathies and aristocratic gravitas helped him lead—but not indulge—the volatile mob who could vote to enslave, murder, or forgive rebellious allies as it saw fit on any given day.

True, Pericles in theory was only one of ten annually selected generals—who were elected by a public show of hands in the assembly and could be reelected each year. Yet his age, experience, character, and rhetoric gave him such wide public support that by sheer force of will he was able to persuade his colleagues either to hold or postpone assemblies of the people, and thus to facilitate or stymie outbursts of popular expression.25

To an approving Thucydides, “in name a democracy, Athens became a government ruled by its first citizen.” Whether such a blanket encomium was entirely an accurate reflection of how politics really worked in Periclean Athens is unclear, especially given Thucydides’ propensity to denigrate the Athenian assembly as a “mob” or “crowd” of poorer and less educated people. But a more salient consideration was that Pericles was now about sixty-four years old. There must have been doubts about whether he possessed any longer the physical stamina to meet the greatest challenge in the history of the democracy.26

What ultimately would betray the great leader were as much lapses in logic as physical exhaustion and age. Pericles was to be proved wrong on all three of his gambles about the coerced evacuation from Attica. The sudden plague that broke out during the second year of the invasions (430) wiped out thousands of the frontline military infantrymen of Athens. It killed or sickened tens of thousands more, thus taking more lives than could any Spartan phalanx, reminding us that in most wars more usually die from disease than enemy iron. He drove his citizens inside the walls to ensure thousands their salvation, but instead guaranteed destruction to far more. Civic tension broke out among various interests that was never completely resolved, but soon manifested itself in precipitate and poorly thought-out offensive operations, and eventually in the two political coups of 411 and 403. To the conservative historian Thucydides, Pericles’ demise was a tragic loss and led to an endless cycle of lesser demagogic figures: Cleon, Alcibiades, Hyperbolus, Cleonymus, and Cleophon, who all played one faction off against the other in cynical pursuit of personal power.

None of these repercussions was anticipated in late May 431. Then a huge allied army of Peloponnesians, consisting of thousands of hoplites, cavalrymen, and light-armed troops—two-thirds of all available troops in the Peloponnesian alliance—mustered at the Isthmus of Corinth. The mass then slogged its way northward on the first of what would turn out to be five late-spring invasions of Attica over the ensuing decade.

The attack was, in fact, somewhat late. Despite hearing a litany of Peloponnesian complaints against the Athenians during the summer of 432, then obtaining a vote that the Athenians were in material breach of the peace, and finally receiving recent word that their allied Boeotians had preempted them by attacking the Athenian protectorate city-state of Plataea in early March 431, the Spartans nevertheless waited months to advance into Attica. Ostensibly, they had to time their arrival with the ripening of the barley and wheat fields, those crops most important to an ancient city and the easiest to destroy by burning.

In such a huge countryside as Attica, replete with different elevations and microclimates, there might be as much as a two-month divergence in ripening times. Thus, finding some combustible dry grain was no guarantee that the crop just a few miles away would also be mature and vulnerable. Ancient armies usually carried three days’ rations or so, and thus counted on the harvests of the invaded to supplement what little food they brought along. That Archidamus had actually mobilized such a large army composed from so many small communities was miraculous, given the fact that most rural folk of the Peloponnese had no desire to march away and leave their women and children to care for their own ripening crops. Indeed, even if the huge army marched ten abreast, it stretched out for over fifteen miles, as it slowly wound its way northward into Attica. Its belated advance into Attica formally started the Peloponnesian War. As the Peloponnesians at last crossed the border, a Spartan herald returned from a failed last-minute peace mission to Athens, sighing of the enormous army that crossed into Attica, “This day will be the beginning of great misfortunes to the Hellenes.” And so it was.27

None of these contingents would have attacked Athens singularly. But now they swarmed in on two guarantees of their safety: the army was huge and thus invincible, and both the red-cloaked Spartans and the feared horsemen of Boeotia were to run loose at the vanguard in Attica. Who knows all the crazy thoughts that raced through the minds of these opportunists: Might Athens surrender and its plush city be left ripe for plunder? Might its chagrined hoplites march out and meet catastrophe in a glorious Peloponnesian victory? Might twenty thousand farms supply enough plunder to enrich an entire generation? Thucydides wrote of the general Hellenic consensus on the eve of the war—of course well before states had much experience with victorious Spartans as overlords—“It was clearly on the side of the Lacedaemonians.”28

Despite the enemy’s hopes that the overseas tributary allies of Athens would revolt on news that Spartans at last ranged freely a few miles from the Athenian Acropolis, or that the Athenians would cease their blockade of Potidaea, not many subjects believed that Athenian power was in any way eroding. And fewer still felt that their own future would necessarily be any better under Spartan hegemony. Even fewer neutral states sent their young men to join the Spartan crusade. In the chaotic world of some fifteen hundred autonomous city-states—where a few stone ramparts were all that sometimes kept invaders on the horizon out of the agora—it always made better sense on rumors of war to pause, take a deep breath, put aside ideological zeal, and carefully size up the respective strengths of potential allies and enemies before committing to battle. The vote of the Peloponnesian League to go to war was taken in August 432; the army didn’t reach the borders of Attica until May 431. For eight months—almost exactly the period of the “phony war” on the Franco-German border between the invasion of Poland and the attack through the Ardennes (September 1939 to May 1940)—Sparta not only prepared to muster an allied army but, more importantly, hoped for a final resolution that might bring concessions from Athens.29

The Peloponnesians’ trek northward to Athens from Sparta followed much the same route as the modern highway. It is a scenic way that, after leaving the Isthmus at Corinth, traverses the Megarid to the high cliffs above Salamis. Then the route passes the sanctuary of Eleusis, before crossing over the slopes of Mount Aigaleos at the modern suburb of Daphni and finally descending into the plain of Athens. The road is not an easy, level march, and it is made worse by the heat of late spring and the scarcity of water along much of the way. What did tens of thousands of Peloponnesians think of as they hiked along the cliffs that tower over the straits of Salamis, where a half century earlier the grandfathers of both sides had united to preserve Greek liberty?

The mob that advanced was itself larger than all but a handful of Greek city-states, carrying along tons of iron, bronze, and wooden arms and armor, unsure whether the cliffs above would be patrolled by Athenian rangers. However, in this initial invasion before reaching the formal border of Attica, King Archidamus first turned to the northeast. He sought to enter Attica instead by a circuitous route near the northwestern garrison at the tiny hamlet of Oenoë and then to descend into the outlying demes on the lower slopes of Mount Parnes.

There the invaders were immediately confronted with a myriad of more mundane problems, from cavalry patrols and rural Athenian garrison troops to confusion about delegating the tasks of agricultural devastation. Thucydides reports that Archidamus had been slow in mustering in the Peloponnese, slow in collecting the final army at Corinth, and was now slow—or perhaps bogged down—in Attica itself. In the leader’s defense, no Spartan king had ever been put in charge of such a massive coalition army, a force far larger than any commanded later by either Philip or Alexander, both masters of sophisticated logistics. Second, Sparta had never been known for audacity beyond the borders of Laconia; every Spartan commander, with the exception of the rare Brasidas, Gylippus, or Lysander, was at one time or another dilatory in bringing troops to battle, fearful that helots were free rather than farming.

Despite an array of siege engines, the invaders failed to take the Athenian base at Oenoë, which was well fortified, stoutly defended, and a nexus for frequent Athenian patrolling. Soon a frustrated Archidamus moved on, slowly descending to the Eleusinian and Thriasian plains. There he settled in near Acharnae. This was the largest rural deme of Attica, less than ten miles from the walls of the city proper, and its occupation meant a brazen challenge for Athenians to put up or shut up.

The Acharnians, crusty growers who provide the eponymous title of an Aristophanic comedy criticizing the war, may have normally contributed as many as 3,000 hoplite soldiers to the Athenian army. So they were influential folk, farming a large and fertile district of Attica near the slopes of Mount Pentelikos, not far from the city proper. Many made their living by burning charcoal and knew something about fire in the countryside. In Archidamus’ mind, the property of these touchy farmers should be the first Athenian soil targeted, a test case of sorts: the furious Acharnians would either force the others to fight or cause so much dissension inside the walls as to undermine civic support altogether for Pericles’ strategy. In Plutarch’s words, they surely would march out to battle if for nothing other than “angry pride.”30

Despite the cynical Spartan attempt to reveal the fragility of democracy in time of war, Pericles held firm and reined in the Acharnians. In desperation Archidamus ravaged their vineyards and orchards and, when no enemy phalanx marched out, moved out of Acharnae. Pericles had kept sending out offensive cavalry patrols; he may have anticipated the present need, because he’d beefed up the cavalry to 1,000 mounts on the eve of the war. He also made sure not to convene any meetings of the assembly where rival demagogues—the fiery Cleon especially—might excite the mob in these times of stress. In Plutarch’s words, he “shut the city up tight” and “gave little thought to the slanderers and malcontents.”31

For all the supposed political turmoil, the Spartans had, ironically, created a weird, novel political cohesion inside the walls. The poor were busy manning the fleet to attack the seaboard of the Peloponnese to pay them back for their ravaging of Attica. The middling hoplite farmers were angry, but safe inside the walls without the need to confront crack Spartan infantrymen. The wealthy every day were bravely riding out to harass enemy ravagers and did a superb job in curtailing the despoiling of the countryside.32

Frustrated by this repeated inability either to ruin the countryside or to prompt a battle, after a few days Archidamus moved farther on, to the region between Mount Pentelikos and Mount Parnes. From there the Spartans exited Attica through the northern borderland of Oropus. The army ended up in neighboring and friendly Boeotia before trudging back home a few weeks after it mustered.

In prewar discussions it was little remarked upon that Athens, in fact, had a two-front war on its hands: Peloponnesians to the south, Boeotians on the north. Already, in the first days of the fighting, the Athenians were learning that not only could opportunistic Boeotian raiders plunder with near impunity from the nearby border but also that the Spartans could not really be bottled up in Attica and denied safe exit. They needed only to march on through to Boeotia, rest, replenish their supplies, and then if need be take a circuitous route home that bypassed Attica altogether.33

For all the size of the first attacking army, at least two-thirds of Attica was nevertheless left unravaged. In contrast, even if all 1,000 Athenian horsemen had scoured the countryside at once, in theory the cavalry offered a pitiful deterrent. There was only a single defender for every 200 acres of cultivated land. Yet, because the Spartans concentrated on particular hot-button targets in Attica, such as the deme of Acharnae, large bands of cavalry could keep the enemy from fanning out too far from the main body. On this first inroad it seems that Archidamus’ dilatory progress and his decision to concentrate mostly on those rich demes within sight of the walls of Athens were designed to provoke rather than ruin the Athenians.

Again, what is striking about both ancient and modern Attica is its vast size, over one thousand square miles, making it one of the largest rural territories of any polis of the ancient Greek world. If half the arable land of Attica was cultivated in olive orchards (e.g., about 100,000 acres, with 50 to 100 trees per acre), there might have been planted anywhere from 5 to 10 million trees! Ravaging all these groves was an impossible task of complete destruction, especially after the initial invasion of a purported 60,000 Peloponnesians, when the enemy probably mustered only about 30,000 in four subsequent inroads. In a few weeks’ time, a single hoplite or even a light-armed ravager could hardly hope to cut down, on average, 250 trees, especially when the countryside was still alive with horsemen and a few angry recalcitrant farmers.

Because Attica was so large, an entire corpus of Greek literature attests that even in peacetime many Athenian rustics had never ventured into the city at all. This parochialism was not surprising, since some farms were fifty miles distant from the Acropolis and a long hike away.34 Athenian strength cannot be calibrated only through its silver mines, fleet, and income from overseas tributary allies. Like Sparta and Thebes, much of Athens’ financial power accrued from its large rural territory and population. For all the attention paid to gold, silver, and manpower, the real players in the ancient Greek world—Sparta, Athens, Thebes, and Corinth—were precisely those states that controlled the largest or most fertile tracts of farmland, the ultimate source of all wealth in early, preindustrial societies. Even today, despite the unchecked urban spread of Athens, its new sprawling rural airport, and thousands of impressive country homes, there are still tens of thousands of acres in small valleys and plains that are hard to reach and often quite isolated, from the foothills of Mount Parnes to the interior plains and vales of Laurium, some fifty miles to the south.

Earlier, before the campaign had even begun, King Archidamus—in Thucydides’ history a tragic Hamlet-like character who hesitates before striking—had outlined to the Spartan assembly his doubts about systematically ravaging the entire Athenian plain and his belief that Greek farmers would still negotiate rather than see smoke arising from their farms. So he voiced his concerns on mostly strategic, if not psychological, grounds: “Do not consider their land anything other than a hostage to hold, and it is a better hostage the better it continues to be cultivated.”35

Later a popular theme of historians was cataloging those areas of Attica—Decelea, the plain of Marathon, the Academy (the future site of Plato’s school), and various private estates with the so-called sacred olive trees—that despite five annual invasions were never attacked and thus perhaps never evacuated. Rumors had it that the Spartans might also skip rural property of some elites who might thus come under suspicion of philo-Laconism or sympathy with right-wing Spartan oligarchy. And if farms like those of wealthy Pericles were spared, it would only inflame public opinion and divide the citizenry over issues of comparative sacrifices under such an unpopular tactic of forced withdrawal. Something besides mere destruction of crops was going on in the mind of Archidamus.36

At news of their coming—the Athenians had several days’ notice from spies and scouts—the reaction was immediate for those in the path of the ravagers. From public documents on stone, it seems that even before the war the Athenians had made some arrangements to evacuate property from rural shrines, as if they anticipated just such an eventual Spartan invasion. Thucydides, who was sympathetic to the landowning class and may have witnessed firsthand the evacuation, wrote in graphic detail that many rural Athenians carted their belongings inside the walls of Athens. There they hunkered down and counted on cavalry patrols to pick off isolated parties of ravagers.

Urban crowds gathered to argue and fight over the wisdom of withdrawal, something unheard of for almost a half century, since the legendary general Themistocles had organized the flight to the adjoining islands and the nearby Argolid in consequence of the southward advance of Xerxes from Thermopylae. Thucydides’ description of this heartbreaking trek into the city is one of the most moving in his history:

After listening to Pericles’ exhortations, the Athenians were won over and so brought in from their fields their children, wives, and all their household furniture, even stripping the very woodwork from the homes themselves. They sent their sheep and draft animals to Euboea and the nearby islands. But the evacuation was a difficult thing for them to endure because for most they had always been accustomed to live in the country.

Later he adds, “They did not find it very easy to evacuate their homes, especially because it was not that long ago since they had reestablished their estates after the Persian Wars. So they were depressed and took it hard to have to abandon their homes and shrines.” This sudden entry of thousands of rural folk into the walls of Athens between 431 and 425—the catalysts of the plague of 430—caused a radical shift in Athenian society itself. Heretofore most farmers and rustics had kept away from the city. Now they were everywhere. Literature of the war, especially Aristophanes’ comedies, for the first time in the history of Athenian letters began to see things from the mostly forgotten view of the other Greeks outside the walls.37

The sheer work involved in ruining grain fields might explain stories from later Greek history that sometimes armies brought along special wooden tools, so ravagers might more easily beat and break down the still-green grain shoots. Buildings required even more work, making us wonder whether the laments of lavish estates lost always ring true. Houses, as was true in much of Greece until the mid-twentieth century, were built of mud brick with tile roofs. It was not so simple to knock these nonflammable structures down. The only sure method was to torch their interior wooden support beams and hope for collapse. That, too, was a time-consuming challenge, especially when most of the accessible woodwork and doors that could be used for fuel had already been stripped and evacuated. The paltry remains of the foundations of some prominent classical Athenian farmhouses have been excavated in vulnerable places on the spurs of Mount Pentelikos, the coast at Vari, and near a strategic pass on Mount Parnes. None of them seem to reveal damage or destruction from the later fifth century, suggesting that they either were not seriously attacked or were skipped altogether.38

As Spartan infantrymen in small patrols tried to protect the ravagers from Athenian cavalry, the mob of destroyers sought to plunder all that they could carry and eat as they burned and cut. But soldiers, ancient and modern, are trained to fight, and thus infantrymen make less effective looters, engineers, or peacekeepers. The war had surely started, but the initial theater of operations involved no pitched battles, clashes at sea, great sieges, or even terrorist raids, and thus for many Greeks this was already a strange sort of fight, especially given the huge army of Archidamus and the even larger numbers of Attic residents who retreated into the walls.

In the comedies Acharnians (425) and Peace (421), Aristophanes presented smart-alecky Athenian farmers as wiser than their leadership and slowly radicalized in their anger at the enemy, their own political leadership, and the war in general. These unsung stalwarts were furious that beloved estates were allowed to be overrun by enemy vandals. “I really hate the Lacedaemonians,” the hero-farmer Dicaeopolis (“Just City”) laments in Acharnians, “for in my case too there have been vines cut down.” There are plenty more admissions in contemporary literature that the Spartans did not do too much damage, at least in these brief initial annual invasions. Thucydides describes the agony of the losses and yet alludes to areas of Attica that were either not touched at all or not systematically destroyed. In the seventh book of his history, he flatly declares that “the invasions had been short” and had not stopped the Athenians from “making full use of their land during the rest of the year.” But how, then, could he later conclude that Athenians made “full use” of Attica before and after a huge Peloponnesian army arrived to ruin it?

As is his wont, Thucydides’ generalizing conclusions (e.g., little damage) are often at odds with the gripping description of ravaging presented in his narrative (e.g., apparently lots of ruin). And his contemporary observations are sometimes reemphasized, modified, or even contradicted later in his text, as in the later revision he did not always change his working draft to reflect his final conclusions at war’s end.

An anonymous fourth-century historian agreed. The author—his work is known only as the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia, named after papyrus fragments found at Oxyrhynchus, Egypt—declared that Attica “was the most lavishly furnished area in Greece.” The reason was that “it had suffered but slight injury from the Lacedaemonians” during the invasions of the Archidamian War.39 The phrase “slight injury” perhaps implies that 60,000 ravagers in 431 could do little amid 200,000 acres of farmland.

For all the comic poet Aristophanes’ emotional and wrenching descriptions of ruined vines and trees, remember that his first extant play was not produced until the year of the last invasion, 425. Was he a realist observer or a fictive playwright playing on the anger of the recent past? Moreover, an equal number of his passages suggest that much of the Attic countryside did not suffer serious damage. In Sophocles’ famous Oedipus at Colonus, a tragedy produced after both the agriculture devastation of the Archidamian War and the occupation of Decelea by the Spartans in 413, the playwright could call the Attic olive “a terror to its enemies” that “flourished most greatly in this land.” The Sophoclean olive of Attica was a tree that no young or old man could “destroy or bring to nothing.” Audiences in the theater would have found such an ode a cruel joke if they had gazed out at millions of stumps in the countryside.40

All this skepticism makes sense. The first decadelong phase of the conflict, referred to as the Archidamian War, actually saw little real fighting inside Attica. The Peloponnesian invasions were fast becoming a phony theater. Tempers flared, but few died in actual combat. After the first invasion of 431, the enemy came only four more times. Perhaps they stayed no more than 150 cumulative days during the entire decade between 431 and 421! None of these subsequent ravaging expeditions were as large as the infamous inaugural attack of 431, although the first two invasions were considered the most massive and together delivered a one-two punch that inflicted deep psychological wounds on the rural people of Athens. To put it another way, between 431 and 425 the marvelous Spartan army was used against the Athenians in Attica only three of the first eighty-four months of the war.41

Perhaps Pericles’ war of attrition, funded by capital reserves, really would wear down the Peloponnesians after all, causing faction among such a loosely connected alliance that lacked the money and unity of the Athenian empire.42

An exasperated king Archidamus came back a year after the first inroad and tried to be more systematic in his second attempt at destruction. In 430 he remained about ten days longer, perhaps because his army was about half the size of the massive force of the year before and far easier to feed. He now set out beyond the Attic plain, moving into the coastal regions as far south as the mines at Laurium. Thucydides believed that the longer stay, coming after an initial inroad, and the more area that was devastated at this time, made the Athenians later feel that it was the worst of the five invasions, prompting them to prepare to send envoys down to Sparta to talk about a possible armistice.

Perhaps Archidamus reckoned that in some strange way his show of force might precipitate a revolt of Athens’ island subjects who saw their master tied down in Attica. Thucydides says little more of this second invasion of late May 430 or even of the next two subsequent attacks of 428 and 427, other than that the enemy now tried to destroy crops that had been bypassed or had grown out again, presumably vineyards and orchards that had sent out new shoots. Apparently King Cleomenes, not Archidamus, led the fourth invasion of 427. He made a systematic effort to cover Attica, as well as retracing Archidamus’ earlier trail, aiming to hit farms that were in the midst of recovery.43

Fear of the plague had scared the Spartans off from a planned third annual invasion in 429. They instead abruptly headed to Boeotia to besiege the Plataeans. In 426 they also kept away, purportedly because of an earthquake. The real reason was probably apprehension of a recent renewed outbreak of the pestilence. If the key to agricultural devastation was repeated ravaging to wear out a rural population and prevent repair and renewal in the hinterland, then the Spartans’ crusade—eventually conducted under the tenure of three different kings, Archidamus, Cleomenes, and Agis, son of Archidamus—was proving to be an utter failure. No Spartan commander was ever able to regroup and mount a second attack in the same year. That persistence might have at least shown that they were serious about either ruining the countryside or making it impossible for farmers to return during the growing season. Why the Spartans kept coming into Attica without altering their tactics is one of the great mysteries of the Peloponnesian War; after 430 they apparently felt that Athenian evacuation was exacerbating the effects of the plague and ruining the city, inasmuch as it was clear that they were neither destroying the food supplies of the city nor cutting off access to the countryside.

The fifth inroad of 425, led by the young Agis, was a disaster. It lasted only two weeks. The grain was too green to be either consumed or burned. But, more importantly, the invaders were hysterical at news that 292 Lacedaemonians—among them 120 elite Spartiates—had been captured off the coast of the Peloponnese at Sphacteria and held as hostages in Athens.

In none of these invasions did the Peloponnesian grand army disrupt the mining operation at Laurium and thus cut off the source of Athenian silver coinage. After 425 the Spartans would not reenter Attica for the rest of the Archidamian War in fear of Athenian threats that their prisoners would be executed if an army ever again crossed into Attica. The Attic war was now for all practical purposes over.

Like most campaigns, it was one thing to talk grandly of a walkover of the enemy’s homeland, and quite another to see it through. No one in May 431 could have dreamed that in a mere six years hostage taking—brought about by the surrender of crack Spartan hoplites no less!—could prevent an army of thousands from even crossing the border of Attica. Even before the capture of the Spartan hostages, the reluctant Peloponnesian allies complained to their Spartan leaders that they were busy with their own crops and, despite witnessing almost no combat, were in “no mood for campaigning.”44

If what had once been a parochial tool to incite hoplite battle was now to be an integral tactic in causing general economic dislocation, there is no sign that armies discovered any new technologies to destroy cropland more effectively with special fuels, arms, or troops. True, in some cases like the seaside town of Acanthus in northern Greece, which was dependent on the export of its wine, fear of the loss of its vintage by armies arriving shortly before the harvest could bring concessions. But with the rise of walled cities in the fifth century, a town that had brought in its grain often ignored enemy provocations and worried more about siege troops than ravagers.45

A good example was Pericles’ retaliatory plan of semiannual invasions of the nearby farmland of Megara, to the south. After the departure of the Peloponnesians, when it was clear no sizable army was around to face his Athenians in battle, he mobilized his hoplites. Ten thousand ravagers in vengeance devastated the nearby Megarid, a plain centrally located on the Peloponnesians’ route into Athens. Although the grain harvest was already in, such a large and unmolested force must have done some short-term damage to local farms on the borders of Attica; the area is remarkable in modern times for its large olive groves. But, again, the real purpose was psychosocial and political. Pericles’ bullying army wished to vent its rage at an enemy who weeks earlier had helped to attack Attic farms, to humiliate the Megarians for aiding the transit of enemy invaders, and to cause civic dissension that might lead to a democratic and thus friendly change of government curtailing the Spartans’ ability to march freely into Attica.

Yet for all the ceremony of Pericles’ massive force of ravagers (“the greatest army of the Athenians ever brought together”), Megarians kept inside their walls and stayed allied to Sparta. Thucydides adds that by 424 the Athenians had invaded Megara twice every year. If he is right, that means an incredible fourteen invasions with an infantry force that might on some occasions have numbered 10,000 soldiers in the field, ironically a testament to the difficulty of even large forces over time to starve a people out or obtain concessions.46

Contemporaries remark frequently about the five Peloponnesian forays into Attica, but almost never about the fourteen Athenian invasions of Megara during the same period. In terms of simple manpower, the Athenians may have sent collectively 140,000 ravagers into the narrow Megarid (fourteen invasions of 10,000 troops each), about the same as the number of Peloponnesians who cumulatively ravaged Attica (five invasions of about 30,000 troops), but unleashed on a smaller geographical area. Yet neither strategy brought the enemy to its knees, much less resulted in a decisive pitched battle.

The spartans learned that they needed to stay in Attica year-round in a fortified garrison—the dreaded strategy in the second phase of the war that would come to be known as epiteichismos (“forward fortification”)—where the aim was to loot, keep farmers away from their fields, and create a clearinghouse for plunder and booty. Consequently, the Spartan garrison at the fort of Decelea, thirteen miles from the walls of Athens, fortified in 413, caused more material harm to Athens by disrupting commerce, interrupting communications with the supply depots on nearby Euboea, encouraging the flight of slaves, and keeping farmers from their fields, than all the futile earlier efforts at chopping and burning trees, vines, and grain during the Archidamian War.

The young King Agis, who had led the last failed Spartan invasion of 425, came back over a decade later to Decelea as a mature commander who now had the resources, insight, and the firsthand experience to craft a tactic that avoided the pitfalls of his prior failed invasion. The fortification of Decelea—urged throughout the war by an array of Spartans and allies—proved one of the brilliant strategies of the entire conflict. It made the Spartans’ effort at rural plundering immune from the cycles of the agricultural year and offered a permanent redoubt and refuge from counterattacks and cavalry patrols. With a year-round base, the invaders could arrive well before the harvest and stay after it was over, depending on constant plunder, theft, and stout walls for their sustenance and protection.47

But Decelea was a decade in the future, after the Spartans at last vacated Athens in 425. In some ways the idea was a fluke, growing only out of the reaction to the earlier flawed strategy of annual invasions, recent promises of Persian money, and the depletion of Athenian manpower brought on by the disaster at Sicily. Usually the Spartans abhorred forward basing, and thus entrusted such risky operations to expendable lesser-bred mavericks like a Lysander or Gylippus, who might better lead ex-helots and mercenaries than precious Spartiate hoplites.

For the German military historian Hans Delbrück, such total war evolved into a more complex strategy of attrition waged against the moral and economic capital of a state rather than the more straightforward idea of annihilation in which an army seeks to destroy through hammer blows its counterpart in the field. Why waste lives battering away at like forces when softer and more important resources could be targeted over a longer period and at much less cost? Could a Greek polis really win a war by ignoring the main infantry forces of its adversary in the field? Pericles thought so. The morality of waging exhaustive war was a new and unsettling enterprise for Athens and Sparta, as both sides lacked accessible hard targets and thus soon sought to prevail through ruining civilian resources and attacking third parties.

Yet by not coming out to fight, did Pericles guarantee the death and ruin of the civilians of Athens, both inside and outside the walls, in a vain hope of wearing down his adversaries in a new total war? It was Periclean strategy, after all, that defined the new war as battle not between hoplites or even sailors but rather soldiers against the property of everyday folks. This moral quandary also remains with us today, and it has been raised in connection with the controversial careers of William Tecumseh Sherman, Lord Kitchener, and Curtis LeMay, who all argued that battle is ultimately powered by civilians and thus only extinguished when they cannot or will not pledge their labor and capital to those on the battlefield.

Was it a more moral and effective strategy to burn the slave estates and ruin the property of the plantation class of Georgia, which had fueled secession, or to have Ulysses Grant kill thousands of largely young and non-slave-owning youth in northern Virginia in open battle? Far worse still, was Curtis LeMay a war criminal who burned down the cities of Japan, killing tens of thousands of civilians with his napalm-fed infernos? Or, in effect, did he shorten the war and punish those in Tokyo’s household factories whose labor produced the planes, shells, and guns without which the Japanese imperial army could never have murdered thousands of innocent Koreans, Chinese, and Filipinos and killed so many American servicemen?

Hans Delbrück was not interested in such abstract moral questions. It was the efficacy of the respective strategies that mattered to him. Delbrück wrote in a defeated Germany not long after the horrors of the trenches of World War I and was searching for a less costly strategy of battle mixed with more comprehensive economic, cultural, and psychological tactics that might still achieve Germany’s strategic aims. He concluded that Pericles had hit upon a formula of success, a strategy that defined deadlock as victory—without ruining armies of young men in the process. Had Pericles lived, had the plague not broken out, and had the Athenians not jettisoned their strategy, Athens could not have been defeated militarily and might have obtained far earlier roughly the peace it found in 421—without thousands of its citizens dead, its army humiliated in Boeotia, and its strategic possessions in the north in enemy hands. For Delbrück such a stalemate, in the manner of Frederick the Great’s lengthy campaigns, would have eventually won the war for Athens, since its greater capital reserves gave it a resiliency unknown at Sparta. That latter polis, as Thucydides repeatedly stated, had gone to war precisely “in fear” of the growth of Athenian power.48

What, then, had the blinkered Spartans accomplished in Attica during the initial phase of the war? Nothing and everything. Although they had been at war with Athens for nearly seven years, their army had spent an aggregate of less than five months in Attica, and the Spartans’ chief strategy of annual agricultural devastation had achieved none of its objectives. It was not cheap to send thousands of farmers into distant Attica. If the Peloponnesians paid their army at the going rate for military service—150 aggregate days for about 30,000 men at a drachma per day per soldier—the total cost of Archidamus’ five invasions was about 750 talents (about $360 million in modern purchasing power), more even than the yearly tribute income of the Athenian empire, or about the cost to put 250 ships at sea for three months. The outlay was bearable for a rich state like Athens. (It spent almost 4,500 talents on sieges and seaborne operations in the first seven years of the war alone!)

Yet for the rural Peloponnesians, who had little capital at the outbreak of the war and were used to brief campaigns settled by hoplite collisions, going into Attica for the first years of the war was an exorbitantly high price to pay. When the Corinthians clamored for the Spartans to start the war, the chief method that they outlined to pay for military expenses was to tap the rich reserves at the Panhellenic sanctuaries of Olympia and Delphi. How else, after all, could a state that used iron spits for money ever purchase ships, hire crews, or buy food in an open market? For a Greek world that put a high premium on honor and status, the Spartans had demonstrated that they were walking about freely on the sacred soil of Attica while their hosts were huddled inside their walls.49

This war in the fields was more than grand strategy and most certainly was not fought by anonymous thousands. During these annual devastations of Attica a young Athenian noble—acclaimed the most handsome youth in Athens—was slowly emerging from the chaos of war and plague. Alcibiades was just about nineteen when the Peloponnesian War broke out. Months earlier he may have served as a mere teenager with the cavalry at Potidaea during the antebellum siege of that recalcitrant Athenian subject state. By 429 he had returned home to cavalry service and was no doubt in Attica at twenty-one—a hero since he had been wounded at Potidaea and honored with the award of valor despite being saved with his armor by his mentor, Socrates.

Alcibiades’ lineage was Kennedyesque. He would be emblematic of the entire glory and tragedy of the fifth-century Athenian imperial state, which started the war with such high hopes among a generation that inherited the pride but not the sobriety of their fathers. Pericles, after all, had been credited with achieving nine battle victories when the war broke out, and knew well that his majestic temples and the brilliance of Athenian drama conducted below the south slope of the Acropolis were the dividends of decades of hard-fought wars. Alcibiades, in contrast, grew up in the latter 440s and 430s, when the earlier conflicts with Boeotia, Sparta, and the rebellious allies were for the most part over—and the largess of empire already manifest in a bustling port, rampant construction, and a vibrant city full of the likes of Sophocles, Socrates, and Euripides.

From his mother, Deinomache (“Terrible in Battle”), Alcibiades claimed membership in the Alcmaeonids, the most powerful and controversial of the centuries-old Athenian aristocratic clans. His father, Cleinias, had died during the earlier Athenian hoplite catastrophe at Boeotian Coronea (447), after being prominent in establishing the fiscal architecture of the entire system of Athenian imperialism in the Aegean. Three-year-old Alcibiades was entrusted to his distant cousins, the brothers Ariphron and Pericles, who taught him something of the manifest destiny of an ascendant democratic Athens.

Little is known about Alcibiades during his twenty-first through twenty-sixth years, when he may have been constantly on patrol in the Attic countryside as a member of the Athenian cavalry. No account exists about how he avoided the plague that killed his guardian Pericles. Only his early personal life was of much interest; after his return from the siege at Potidaea in the second year of the war, a number of salacious stories immediately spread about his raucous carousing. In between his summers of rural mounted service he drank and argued with Socrates, often became the subject of sexual gossip, and apparently embraced a long family tradition of combining his own aristocratic background with opportunistic democratic politics.

Alcibiades’ sizable family estate in the Athenian plain was probably ravaged by the Spartans, even as he remained true to the Periclean policy of abandonment of Attica while he rode down enemy ravagers on patrol. After the Spartans ceased their annual incursions, Alcibiades nevertheless reminded the Athenians of their duty to protect the sacred soil of Athens. They were to adhere, he stressed, to the old annual oath that the ephebes took on behalf of their alma mater, swearing “to regard wheat, barley, vines, and olives as the natural boundaries of Athens.”*

Later in the war Alcibiades would exhibit a strong desire for the offensive, perhaps as a reaction to the senseless war of attrition in Attica that marked his first years of service. Some eighteen years after the Spartans first marched out to cut down the trees of Attica, a much older and by then treasonous thirty-seven-year-old Alcibiades, ensconced in Sparta, would advise his former enemies that such annual incursions were no way to wreck his homeland. Better, he told his new hosts, to create a permanent fort, thirteen miles from the walls of Athens at Decelea, and thus destroy Alcibiades’ own native soil year-round.50

But all that was well into the future. For now, the teenager rode into battle against ravagers full of zeal and hope, confident after the first year’s assault that Attica had taken the best punch Sparta could offer—scarcely aware that both his country’s and his own greatest tragedies lay just months ahead.

* Thetes (thêtes) were the poorest of the census classes at Athens and elsewhere—in wartime, mostly landless wage earners who either rowed in the fleet or accompanied the phalanx as skirmishers and light-armed troops.

* At Athens, and perhaps elsewhere in the Greek world, ephebes of the upper classes, between the ages of eighteen and twenty, entered a period of mandatory training, often on the frontier and in transition to full-fledged infantry or cavalry service.