Sometimes the sieges of small towns and cities that have little strategic significance—a Guernica or Sarajevo—become emblematic of both the senselessness and the barbarity of war by the fact of their deliberate destruction and the inability or unwillingness of others to save them. So it was with the hamlet of Plataea, which slowly perished in a series of death throes.

Plataea’s eventual capture made very little difference in the larger calculus of the conflict, even though it ostensibly guarded a key pass over the mountains to Attica, and might be an obstacle to any Boeotian army that thought about invading Attica in force from the northwest. As the town died, Athenians fifty miles away and mostly oblivious to its plight died in droves from a mysterious disease, while Spartans sought to cut down olive trees and burn houses in Attica. Yet throughout its four-year ordeal, the on-again, off-again siege to take this small Boeotian hamlet illustrated the multifaceted ways that the classical Greeks assaulted and defended fortified cities. In that sense, the death of Plataea won the attention of Thucydides, who was fascinated by the misplaced scientific genius of both the attackers and the attacked, and saw the strategically unimportant city’s fate as emblematic of the savagery of the war at large.

Today the site is little more than a few stone foundations, coupled with the traces of the circuit walls and towers—most likely the remains of the rebuilt fourth-century town that grew up on the ruins of its fifth-century predecessor. A new paved road, in fact, goes right through what remains of ancient Plataea, almost exactly where twenty-five hundred years ago the Thebans and Spartans so desperately tried to break in. The modern visitor to Plataea rarely sees a single tourist. This solitude is true of most of the killing grounds that dot the Boeotian countryside and were once so famous in Greek literature: nearby Delium (vacation homes now encroach on the landscape where Socrates backpedaled out of battle), Leuctra (a quiet grain field and irrigation ditch mark the spot where Epaminondas crushed the Spartan army), and Chaeronea (now a nondescript orchard where Philip and his teenaged son destroyed Greek liberty).

The fortified city’s end began in peacetime on a late March night in 431, seven months after the Spartans had officially declared the peace with Athens broken, and yet seventy days before they and their allies crossed the Athenian border. The Peloponnesian War ostensibly pitted Athens against Sparta, but its precursors were Corinthian and Theban attacks against the Corcyraean and Plataean allies of Athens.1

About 300 prominent Thebans had secretly made their way to Plataea along the gently rising eight-mile road from Thebes during a rainy cold night. Their oligarchic ringleaders had counted on kindred reactionaries inside the border city to open the gates, since it would have been impossible to storm the walled community by day. Buoyed by the surprise arrival of a foreign force inside the walls, the Plataean zealots could then round up their sleeping democratic opponents, kill their ringleaders, and hand the city over to Thebes. Or so the right-wing conspiracists thought.

Nothing is worse than for a state to have nearby enemies and distant friends—as the lonely experience of Armenia, Cuba, Taiwan, and Tibet attests. Adversaries loom daily on the horizon; far-off allies often pledge support that they cannot really provide, thereby ensuring that their friendship is as costly as it is undependable. The city of Plataea—like poor Poland squeezed between Germany and Russia—had the misfortune of resting on the border of powerful and hostile Thebes while miles away from stronger and friendly Athens.

In fact, for much of the latter fifth century the Plataeans owed their independence from Thebes’ Boeotian Confederacy not to tangible Athenian military assistance or its strategic location on the main road into Attica. Instead, the backward state of Greek siegecraft meant that the city’s impressive stone walls could still guarantee it autonomy from the entire Boeotian Confederacy—despite the latter’s aggregate population of at least 100,000 people and nearly one thousand square miles of territory.

The advantages in the age-old battle between offense and defense lay with the masons and stonecutters, whose stout ashlar courses, towers, and crenellations, and reinforced wooden gates could withstand the ram and the hand-propelled missile. In this age before the torsion catapult and movable artillery—which in the postwar era to come could hurl stones over 150 pounds up to three hundred yards distant—patience, treachery, hunger, and disease were the better assets of the besiegers. The exceptions during the Peloponnesian War when walls were breached are instructive: Torone, Lecythus, and Mycalessus were all stormed precisely because their walls were said to be in a state of disrepair.

Athens was an old enemy of Plataea’s immediate neighbors, the Boeotians. It was no accident, for example, that much of the incest, patricide, and civil strife of the classical Athenian stage—involving Oedipus, Antigone, Creon, Teiresias, Pentheus, and the Bacchae—was situated in or near Thebes, Plataea’s contemporary adversary and the chief city of Boeotia. Nearly thirty years before Plataea’s destruction, Athens had once subdued Boeotia, and for over a decade had reestablished it as a friendly and democratic client state. But when the Athenians in turn were defeated in 447 at the battle of Coronea, and then mostly kept to their own side of Mount Kithairon, Plataea was once more left alone as an isolated vestige of hated Athenian imperialism. Consequently, the Boeotians, during the increasing tensions of 431, preempted the Spartans and sought to win over or finish off Plataea in a cheap victory before the Athenians realized that they were even at war.

Once the Theban advance party got inside and made its way to the public square, everything suddenly went wrong. Their rightist Plataean co-conspirators wanted to kill all the democrats immediately. The more sober Theban invaders instead preferred to awaken the city. By virtue of their unexpected presence they would shock the people into accepting a forceful and peaceful inclusion into the Boeotian Confederacy. Yet it was not a wise thing for right-wing insurrectionists to call for conciliation in the midst of their own nighttime raid on a much larger democratic citizenry—especially when there were no more than 300 of them to bully the opposition.

At first, the “shock and awe” tactics of the small party of invaders seemed to work. The stunned Plataeans were ostensibly pondering the terms. Yet in their ad hoc negotiations the sleepy democrats very quickly awoke to two surprising facts: there were not many Thebans, and there were even fewer of their own traitors who had invited in the foreigners. Within a few minutes they quietly retreated to their homes and plotted a counterassault. Soon dozens began burrowing through the common walls of their dwellings—Greek houses were made of mud brick without reinforcing studs and often had common partitions. Unseen, the resourceful democrats assembled to devise as best they could a sudden counterresponse. In no time they were barricading the streets and charging out en masse to confront the shocked and vastly outnumbered Thebans.

The attackers became the attacked. Everything now turned against this tiny band of Theban interlopers, who, after all, were soaked, tired, and hungry. It was a black night, stormy, without much of a moon: good for sneaking in—terrible for finding a way out. The rain and mud increased the newcomers’ sense of disorientation, but then none of the foreigners knew their way back out of the winding streets anyway.

In a frenzied retreat the Thebans got lost searching for the main gate, through which they had originally entered; it was now mysteriously jammed closed. The 300 Thebans immediately broke into scattered parties. Some tried to climb over the walls—and then mostly perished or were disabled in the subsequent fall of some twenty to thirty feet onto the rocky ground. Others got trapped in dead-end streets and were butchered by their pursuers. Still more were captured hiding in buildings. In a war to decide the future of the Greek world, this preemptive strike was a particularly inglorious beginning.

The giddy Plataeans quickly sent out heralds to abort another and far larger supporting enemy force that was now arriving as planned in front of the city. After battling the rain and a swollen river, the Theban relief columns were shocked to find the city barred. Worse still, a Plataean envoy appeared from the darkness warning them to retreat without molesting any people and property outside the walls; otherwise the summary execution of all their kindred attackers now captured inside the walls would follow. On the first night of the fighting, the Plataeans—not known as a particularly savage bunch—would threaten, and soon carry out, the execution of captives. When the Plataeans got word to Athens of their plight, the first thing the Athenians did was to round up Boeotians residing in or visiting Attica, purportedly to use them as bargaining chips in the war that would inevitably follow from the night attack on Plataea.

Such immediate resort to hostage taking—six years later the Athenians would threaten a similar immediate execution of 120 elite Spartiates should the Peloponnesian army again invade Attica—suggests that the Peloponnesian War was a scab that was torn off, revealing preexisting and deep festering wounds of a half century prior. Scholars who have catalogued all the major massacres documented in our literary sources during the fifth century note the depressing trend: seven massacres in the long history of fighting before the outbreak of the war and some twenty-four near the beginning and throughout the three-decade-long conflict.2

After rounding up Boeotians, the Athenians responded by marching in and leaving a few garrison troops, aiding in the provisioning of the city, and arranging the evacuation of most of the Plataean women, children, and disabled to Attica. Having recovered from their recent nightmarish experience with treachery, murder, and broken oaths, some 480 Plataeans and a few Athenians in the city braced for the inevitable counterassault.

They had a long wait. A surprised Sparta had prior concerns, and instead would soon find itself busy for two seasons of campaigning in Attica before the outbreak of the plague. It is unclear what went on inside Plataea for the next twenty-four months, other than the fact that Thebes apparently could or would not begin a full-fledged siege. Apparently the city was more a ghost town of adult males than a real community, as the tiny skeleton garrison kept watch for an assault that mysteriously did not come. A few rural Plataeans may have drifted back to their farms, making private alliances with the Boeotians who now surrounded the countryside and patrolled the fields. Plataea, in fact, was becoming a matter of prestige for both sides: the Spartans could not afford to allow their Theban allies to fail to polish off a small renegade city, while Athens for the security of its own empire belatedly realized that it was critical to prove that it would pay any price to help save its most proximate loyal ally. That being said, both sides had their hands full a few months later when the real war broke out.

It was not until the beginning of the third year of the war—May 429—that at last the Peloponnesians went into Boeotia to help their Theban allies deal with the festering Plataean sore. Yet even when Archidamus led his massive force up to the walls, he offered two startling last-minute proposals: those Plataeans still holed up in the half-deserted city could either immediately announce their neutrality, let in his garrison, and thereby stay put—and alive. Or, if still distrustful of their Theban neighbors, they might leave the city in safety on the guarantee that their property and land would be looked after under Spartan auspices—with full rent, no less, for a decade or until the war ended.

The Spartans, with a poor reputation for siegecraft, were not exactly eager for a protracted siege, one that even if successful would be costly and beneficial mostly to their mercurial Theban allies, who had acted unilaterally and without prior consultation. Archidamus also remembered the symbolic stakes involved, namely the once gallant role of the Plataeans in the prior Persian Wars (490, 480–479). He was right then encamped near the hallowed battlefield where the Persian army a half century earlier had been crushed by the grandfathers of those now both inside and outside the walls.

The pious Spartan king also had a problem of sorts with ancestral oaths, well known to all the Greeks, that had been pledged to protect the autonomy of Plataea, now by general consent the shared memorial of the Hellenes. The rolling plains around Plataea had, over some fifty years, become enshrined as the Omaha Beach of the Greek world, a hallowed battleground and Panhellenic graveyard where squabbling allies in better times had once fought, died, and been buried together to push back autocracy. It was one of the crimes of the Peloponnesian War that many of the consecrated places of the Persian Wars where Greeks had earlier united to preserve their freedom were slowly to be desecrated by internecine bloodshed: first the battlefield of Plataea; then another evacuation of Attica, but from a Greek rather than a Persian invader; and soon Spartan raiding in the seas off holy Salamis.

The Plataeans asked for, and got from Archidamus, more time, and then immediately once more sent emissaries to Athens to explain their new dilemma. Themselves surrounded by Spartans, the Plataeans also had worries over many of their dependents who for over two years had been residing inside Athens, some as guests, perhaps most like quasi hostages in the plague-infested city. When they received word that real Athenian help was at last on the way to face the latest threat, the Plataeans felt emboldened enough to reject Archidamus’ final offer. They may have recalled that the Spartans enjoyed a poor reputation for storming cities and had failed two years earlier to capture even the small Attic garrison at Oenoë. The Plataeans now braced for the siege.

If it had been a terrible error two years earlier for the Plataeans to break sworn oaths and execute the Theban saboteurs, it was even more disastrous to place the city’s future under the protection of an ally on the wrong side of Mount Kithairon—one at war, beset by a terrible plague, and no more likely to defend a distant and tiny foreign community than it would protect its own farmers and farmland in front of its own walls. In short, the Plataeans on the ramparts seemed to be trapped inside their circuit by the Spartans, even as their families were residing as detainees among their “friends,” the Athenians.

The second assault on Plataea that now followed proved to be the most remarkable example of the multifarious arts of Greek siegecraft during the entire Peloponnesian War. The ferocious attack and spirited defense warranted Thucydides’ full attention, in part because of its savagery and the ingenuity of the combatants. Within a day Archidamus had encircled the entire city with a makeshift wooden palisade, piled together from the limbs of fruit trees that his ravagers were only too happy to cut down. The circumference of Plataea’s walls was only fifteen hundred yards. The Peloponnesian army that arrived in Boeotia probably averaged somewhere around 30,000 combatants, in addition to various servants and auxiliaries. That meant that there were easily over 20 men responsible for each yard of circumvallation, explaining why they finished their first ad hoc blockading fence in about twenty-four hours. Clearly this was a far easier task than ravaging Attica. Unlike the later Athenians on Syracuse, the Spartans grasped that the key to any successful siege was to throw up some sort of makeshift wall immediately, so that from the outset food and water might be denied the enemy. That way they could start the countdown to starvation well before more elaborate and time-consuming permanent walls of encirclement could follow.

Convinced that the garrison was trapped, an impatient Archidamus now turned to building an earthen ramp that might serve as a road right over the top of the battlement. The work on the sloped mound—so famous in the Old Testament sieges and later at the horrific Roman encirclement of Masada—may have been the only instance of such a technique in the entire Peloponnesian War. Yet the Greeks were not unused to this sort of earthen construction. For centuries they had rolled up the column drums and architraves of their archaic temples by fashioning temporary earthen inclines. But whether in peace or war, such construction remained a time-consuming task that took even Archidamus’ huge force some seventy days, or almost double the time he would usually have spent ravaging in Attica.

Immediately the reaction and counterreaction of the combatants reached a fevered pitch, inasmuch as the Plataeans were fighting for their very existence, the Spartans against time itself. Much of King Archidamus’ army was made up of Peloponnesian yeomen who needed to get home and attend to their own summer harvests. Moreover, the besiegers would have quickly devoured most of their provisions and soon found the wheat fields of Plataea insufficient to feed such a horde—itself probably now larger than almost any city in Boeotia.

As the ramp grew, the Spartans added reinforcing logs and stones to keep the earth compact and stable. In response, the Plataeans tried to increase the height of their own wall faster than the ramp could reach them, by adding additional courses of mud brick faced with timber. Just in case the more numerous enemy force might win the race for the top, the Plataeans also secretly bored holes through their own lower walls, right into the foundations of the ramp, and began stealthily removing earth—thus insidiously sinking the entire mound nearly as fast as it was rising! The Spartans countered by stopping up the breaches with makeshift clay-and-reed plugs. So it went, back and forth, on and on, as challenge met response, the Greeks from dozens of city-states now using the same energy and genius that had crafted magnificent temples and created classical literature to fight over the tiny wall of a tiny town.

To cover their bets in case the Spartan mound still rose faster than it could be undermined or outwalled, the Plataeans also erected a new inner semicircular fortification not far to the rear of the old circuit. If the mound went over the original fortifications, the Spartans who stormed in now might be surprised by a completely new rampart, and thus would be forced to start the siege over again.

But the Spartans were just as adaptable. For the first few weeks, at least, they had the advantages of steady supplies of food and provisions, and far more men working to break in than those laboring to keep them out. They now began bringing to bear several crudely constructed siege machines—large timber battering rams, most likely on wheels—and not only pushing one of them up the ramp but banging others against the less-well-defended portions of the fortifications.

Not to be outdone, the desperate Plataeans—they had been engaged nonstop in tunneling, mining, and raising an entirely new wall—began to fashion even stranger counterweapons. Someone thought up the idea of a cranelike device of enormous rope nooses that could be lowered to catch the rams; so the besiegers’ machines were snagged, raised, and then dropped. In case the ram heads were not shattered from the concussion, the Plataeans also crafted twin poles to which heavy beams were chained. The contraption was then extended over the besiegers, carefully aimed, and the timber dropped down to snap the heads off the rams.

Archidamus was utterly exasperated by such pesky ingenuity. Plataea’s skeleton garrison of 600–480 combatants and 120 women cooks—had held off his entire army for weeks. These stubborn defenders showed no signs of either starvation or civil dissension, the usual indications that capitulation was imminent. If ravaging had proved futile in either starving Athenians or prompting battle, siegecraft was proving even more maddening.

He next turned to fire. His engineers sought to burn down the city they could not storm. Brush was dropped from the mound and piled in next to the wall. More was thrown over the ramparts. Pitch and sulfur were mixed, poured on the piles, and then lighted. If the fire did not weaken the mud bricks and their wooden supports, then perhaps the fumes would sicken the garrison. Thucydides believed that much of the city would have been engulfed had the winds been favorable and the weather stayed dry.

Instead, the breezes remained calm and sudden rains came. The fires burned out without damaging the stone walls and their timber braces or the wooden supports of the houses inside. Nor did the smoke from such a sulfurous mixture incapacitate the defenders—if that was also an intent of the conflagration.

With the failure of the fire attack, coupled with the discovery of the Plataeans’ new secondary wall, the Spartans felt stymied. It was now late September. They had been stuck at Plataea for over three months with nothing to show for their efforts in a backward hamlet. If anything, Archidamus was proving to neutral Greek city-states that the Spartan reputation for incompetence in taking fortified positions was largely justified—a disastrous development for a state that exercised sometimes tenuous authority over a number of fortified cities in the Peloponnese.

Allied troops were restless. Archidamus finally realized this when he conceded that he could neither take nor afford to abandon the city. So he compromised somewhat, allowing most of his hoplites to trudge back home to the Peloponnese, as he marshaled some others to build a more permanent wall of circumvallation to augment the temporary one of local fruit trees. Now his men set to work digging trenches on both sides of a circuit of twin walls. That way they sought not only to extend the height of the ramparts and create protective moats but also to provide mud bricks for their construction.

In fact, the Peloponnesians were building a curious circumvallation like nothing seen before in the history of Greek siegecraft—albeit on a smaller scale, perhaps as sophisticated as Julius Caesar’s twin palisades some four hundred years later at the siege of Gallic Alesia. Two parallel walls rose about sixteen feet apart, roofed in between, and outfitted not only with towers, battlements, and gates but also with interior quarters for the garrison. While the parapets must have been somewhat flimsy—some escaping Plataeans would later knock down a section as they scaled the wall—the besiegers would still have good shelter for the winter, while remaining protected from sorties from both the city and the surrounding countryside.

To take the city, in other words, Archidamus had essentially built an alternative city in the middle of nowhere. His fieldworks were double the circumference of Plataea’s own walls and nearly as elaborate. When he finished, he further divided his army and left behind a garrison, splitting the responsibility for the strangulation of Plataea between Peloponnesian forces and local Boeotians. To a neutral outsider, all this labor and capital expended on a mere hamlet was nonsense; but to the Peloponnesians and their Boeotian allies, Plataea had now become a symbol of both their intent and their ability to wage a murderous war against the Athenian empire.

The courage and genius of the Plataeans for a time won out. But they soon realized that with the erection of this curious barrier they could neither leave nor be rescued. Still, the stalemate now persisted for yet another year and a half after Archidamus departed—or about forty-five months since the initial night attack by the Thebans. In the meantime, Pericles had died; Attica had been ravaged twice; the plague had killed over one-quarter of the Athenian population—and 600 defenders of Plataea went about surviving in a ghost town on ever-dwindling stored provisions, long abandoned by most of its inhabitants and mostly forgotten by their beleaguered and disease-ridden Athenian would-be protectors across the mountain.

In 429 the citizens of the northern state of Potidaea had finally given up their city to Athenian besiegers, an ongoing blockade that mirrored the contemporaneous siege far to the south at Plataea. The surviving Potidaeans were starved out, and allowed to leave with the clothes on their backs and a tiny amount of road money to see them on their exodus. At the time, the harsh treatment accorded the Potidaeans—captives after hoplite battle were usually exchanged or ransomed, and nearby civilians left alone—must have outraged the Greek world, the ripples of indignation lapping all the way to the ongoing assault at Plataea. If the fate of Potidaea steeled the Spartans to persevere against the Plataeans, they should have remembered that the Athenians had at least not executed those who surrendered. But in the future, with the fate of the soon-to-be murdered Plataeans also on their mind, the Athenians would rarely show any mercy at all.

The last phase of Plataea’s long ordeal came to an end through slow starvation. But first, in December 428, almost four years after the Thebans had burst into the city, the beleaguered garrison voted for breakout. About 220 of the most audacious snuck out of the city—on a night as rainy and moonless as the initial Theban assault years earlier. The fugitives scaled the twin counterwalls with specially measured and constructed ladders, killed some of the occupying garrison, and escaped to Athens. The breakout was brilliantly planned, inasmuch as the ladders’ height had been specially calibrated to specification by counting the courses of bricks in the enemy counterfortifications. And the escapers had waited for a dark wintry night, even as the remaining garrison in Plataea provided diversions.

Each man went out with one foot bare to ensure good stability in the mud. Only a single Plataean was captured and a few others turned back; in all 212 Plataean men, over a third of the skeleton garrison, escaped. While their departure meant less mouths for the city’s dwindling food supplies, it also left the desperate defenders with almost no ability to continue the watch on the ramparts, in theory a mere 267 men and women of dubious health to guard some fifteen hundred yards of parapet.

Each defender would now be responsible for over five yards of the circuit walls. The Spartans could take the skeleton garrison almost anytime they wanted, although they were still wary about storming the ancestral home of such an honored people. Thus, rather than go over the walls, they felt it wiser that the few Plataeans left sue for peace and surrender, inasmuch as they could later claim in any peace negotiation that the city had not been stormed and needed to be given back, rather in the manner of a convert that had voluntarily joined the Spartans and their allies.

At the very time the end was nearing for the trapped Plataeans, their Athenian benefactors a mere fifty miles away ignored the besieged and were instead concluding yet another successful assault of their own against the rebellious Mytileneans on Lesbos, across the Aegean. After the capitulation of the city, the Athenians executed over 1,000 of the ringleaders of the revolt and turned all their confiscated land over to Athenian settlers. Among the captives was a Spartan expeditionary officer, Salaethus, who asked to be spared on the condition that at the eleventh hour he could use his influence to call off his comrades’ siege at Plataea. But the obdurate Athenians were more interested in killing an elite Spartan than in saving a few Plataeans who had foolishly taken them at their word of protection some four years earlier, during a time of peace when Pericles was alive and the plague unknown.

So Plataea fell shortly after the Athenians razed Mytilene, during the summer of 427, at the start of the fifth year of the war that had begun so much earlier with the Theban assault. The emaciated defenders left behind finally gave up, unable to meet one of the stronger Spartan probing attacks. Thucydides records the surrender negotiations, making special note of the poignant speech of the Plataean captives. They recited to the Spartans a litany of reasons why and how the entire calamity had begun years earlier when such a historically honorable people had been so unjustly attacked in a time of peace.

The furious Thebans demanded an opportunity to refute the captives as they insisted on collective death sentences. In the end the Spartans worried over the sheer embarrassment of it all, almost four years and thousands of man-hours wasted to capture a tiny garrison. Probably no more than a couple hundred men and women from the original defenders were still alive. Anger over their failure and the need to pacify the frustrated Thebans sealed the fate of the Plataeans.

The captives were asked once more a single question: had they done anything to help the Spartans in the present war? It was a silly inquiry: what chance had the Plataeans had to help either friend or foe while they were trapped inside their city for four years? When they each replied no, the adult males were executed on the spot. The women and children were sold into slavery.

Plataea itself, like Mytilene a few weeks earlier, was razed. The booty from its ruins was used to build a precinct to Hera, as if a symbolic act of piety could assuage the sins of invading a neutral city in a time of peace and executing the descendants of the heroes of the Persian Wars. The neighboring Boeotians, who had started it all by attacking sleeping civilians, rented out the surrounding farmland from the new Spartan owners, who desperately wanted some recompense for a costly fiasco that had gained them little strategic advantage. Thucydides ends the sad tale with the matter-of-fact statement “Such was the end of Plataea in the ninety-third year after she became an ally of Athens.”3

The lengthy siege also fascinated the historian, who returned to the ongoing four-year saga of the garrison three times in his narrative. What can one learn from the poor Plataeans’ debacle about the status of Greek siegecraft? First, it proved almost impossible to storm a walled city without artillery, movable towers, light-armed skirmishers on scaling ladders, and plentiful archers and missile troops. For all the impromptu ingenuity of the attackers, the Peloponnesians were the wrong type of besiegers, the majority of them clumsy hoplites, and they employed only primitive battering rams and covered sheds. The Plataean escapees, when lightly armed and equipped with ladders, proved more adept in going over the Spartans’ elaborate double walls of circumvallation than the Spartans did in trying to break through the city’s ramparts. Plataea’s walls, like those of so many of the Greek city-states, seem to have been beefed up in the decades preceding the war on the assumption that the advantage in contemporary sieges was always with the defenders if they had strong stone ramparts.

Second, taking a city really meant starving the people inside. The only sure way to reduce a Greek garrison was through famine brought on by walling it off from both its own land and relief sorties from abroad. But a land power like the Peloponnesians was oddly ill-suited for such a task. Soldiers had their own harvest commitments back home. The moment an army arrived, the clock began ticking to determine whether the defenders or the attackers would first run out of food and water. The odds should have favored the besiegers. Yet their greater numbers, unfamiliarity with the local landscape, and worry about hostile relief forces could sometimes leave them as hungry, thirsty, and sick as those inside the city. In addition, in almost no case of any major siege, whether at Plataea, Mytilene, or Melos, did either Athens or Sparta commit sizable relief forces to save their respective beleaguered ideological allies. True, the Peloponnesians belatedly sent help to Syracuse, but only after a year of warring there, and more with the idea of hurting Athens than saving the Syracusans.

Sieges were ostensibly between conventional adversaries within and outside the walls. In fact, they were often precipitated by, and sometimes resolved through, the intrigue and treachery of zealots and foreign agents. The exorbitant expenses incurred at Plataea—most of the rural plunder had been carted off by the Boeotians and the vast majority of citizens had long ago left the city with their valuables—also had a catastrophic effect on the Spartans’ willingness to engage further in such high-stakes intrigue. Plataea had cost much and, when taken, had given them back very little. Instead, as the war evolved sieges would increasingly become mostly a specialty of the Athenians, who were far better able to pay for them—and had far more subjects willing to revolt.

The Peloponnesian War, a supposed fight between the Athenian fleet and the Spartan hoplites, began with the siege of Plataea and ended almost three decades later with the blockade of Athens. In fact, even the precursors to this war involved sieges. The Corcyraeans surrounded the northwestern Greek city of Epidamnus, and the Athenians struck at Potidaea, as such naval powers sought to guarantee that subservient and tributary port cities stayed in line.

Attacking cities was not new in Greek warfare. It was as old as Troy and the mythical assault on Thebes by the seven Panhellenic heroes. Sieges were how the Athenian maritime empire was acquired and held at places as distant as Eion, Sestos, and Samos. Yet the growing frequency of such long-term, elaborate blockades was also a result of the rising wealth of fifth-century Greece, which could afford such costly investments.4

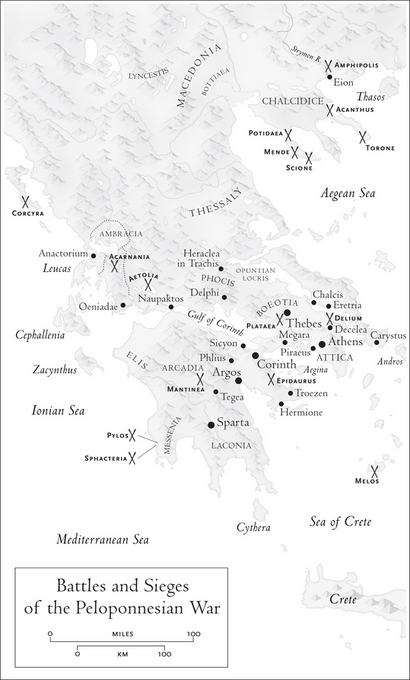

Depending on how one defines a proper “siege”—whether a surrounded rural garrison is to be accorded the same status as an entire beleaguered municipality—there were probably at least twenty-one of them during the war, or almost one for every year of formal hostilities. Some were elaborate efforts against large cities like Potidaea, in northern Greece (431–429), or Syracuse (415–413), in Sicily, perhaps the largest state of the Greek-speaking world. Others involved smaller towns such as Plataea (431–427) and Melos (415). Sometimes sieges were little more than armies cutting off garrisons behind ad hoc fortifications, such as the Spartan attack on Oenoë (431) or the Theban assault on the sanctuary at Delium (424), both of which were full of soldiers rather than civilians.

The ubiquity of sieges cannot be appreciated by their mere numbers, but perhaps is far better indicated by the aggregate years invested by the combatants in besieging strongholds. For example, four years were spent at Plataea, three at Syracuse, two at Potidaea, and two at Scione. Most likely some citystate was under assault somewhere during almost every month of the Peloponnesian War, from Sicily in the west to Asia Minor far to the east, from northward regions of Byzantium to the southern Aegean. While her enemies were busy in the on-again, off-again operations against nearby Plataea, Athens was conducting far more extensive sieges at Potidaea and then Mytilene. With many more sieges than hoplite battles—twenty-one sieges versus two major hoplite battles—the practice of Greek warfare had changed almost overnight.

During some years of the war, numerous Greek cities and garrisons were under simultaneous assault. Between 424 and 423, the Athenians were blockading Megarian Nisaea, while up north they undertook a series of concurrent attacks on Torone, Mende, and Scione, even as the Boeotians were besieging the Athenian garrison at Delium and the Spartans stormed a fortress at Lecythus. In terms of overall battle casualties, while exact figures are few, during the war far more Greeks perished either at sea or attacking and defending cities than in infantry battle. Between 416 and 413, for example, the Athenians and their allies annihilated many of the male residents of Melos and Mycalessus, even as they lost nearly 45,000—many of them considered the best of the Athenian empire—in a vain effort to storm Syracuse. In fact, the greatest disasters in the history of the Athenian empire were due to the two colossal failures at Memphis, Egypt, before the war (454) and on Sicily, both failed sieges that may have together cost over 90,000 Athenian imperial soldiers. Add in the plague, and in a mere forty years the empire lost nearly 200,000 of its resident population as a direct result of warring apart from the traditional battlefield.

Some general trends during the war emerged from all of these bitterly contested assaults. First, most sieges were conducted by the Athenians. Although there were a few cases beside Oenoë and Plataea where the Spartans and their allies attacked smaller city-states and garrisons (more often at near the end of the war at Lecythus, Iasos, Naupaktos, and Cedreae), they very rarely tried to take major cities through formal assault. Something on the scale of the Athenian blockade of the port cities of Potidaea, Mytilene, Melos, or Syracuse was beyond the Spartans’ expertise and resources, until they built a fleet with Persian money.5 Yet at the very outbreak of the war, despite being completely incapable of conducting a siege against the walls of Athens or even a small rural Attic garrison at Oenoë, the Spartans showed some imagination at Plataea in fabricating a mound and some primitive rams and engines, before achieving capitulation by eventually starving the defenders out. So there is a better reason to explain why siegecraft during the Peloponnesian War was mostly an Athenian enterprise, and it involves the asymmetrical nature of the struggle itself.

For most of the war until its last decade, Sparta and its allies did not possess enough ships to patrol in force the Greek coast, much less the Aegean. Its ability to project power beyond the normal land routes was limited in comparison with that of Athens, which, in contrast, brought besiegers by sea to assault distant Potidaea, Mytilene, Minoa, Mende, Scione, Amphipolis, Melos, Syracuse, Chalcedon, and Byzantium, cities from Sicily to the Black Sea that were over a thousand miles apart.

Athens had displayed expertise in fortification with its vast circuit of walls surrounding its own city. Sparta, in contrast, had no ramparts; its port at Gythium was some thirty miles distant. A people that knows how to build battlements at home can better build or storm them abroad. Much of the Athenians’ policy of walling besieged cities off from the sea was the reverse policy of their own construction of the Long Walls to the Piraeus, and so they were intimate with both the procedure and the psychological implications of having a fortified port.

The siege of Plataea was singular not merely because of its length and bizarre tactics but because there was nothing quite like it again, given that there were very few well-fortified inland city-states in southern or central Greece that were not already allies of the Spartans and Thebans. The great prizes in the Greek world—Syracuse, Athens, Corinth, Corcyra, Argos, Byzantium, Samos, and Mytilene—were either on the coast or connected to it by long walls. No state could attempt their capture without a large fleet that ensured naval superiority.

Unlike Sparta, in almost every case where siegecraft was called for, Athens assaulted its own rebellious tributary subject states, such as Potidaea and Mytilene. On rarer occasions, it sought to coerce neutrals, such as Melos or Syracuse, into the empire. Athens almost never conducted a large land invasion of Spartan, Corinthian, or Theban territory to carry on lengthy siege operations against an interior enemy city—impossible operations all, cases where its supply lines were untenable and its vast fleet of no use.

As the Athenians put it to the Melians in their famous dialogue in the fifth book of Thucydides’ history, their chief worry was not really Sparta and its allies. Rather, the problem was Athens’ own “subject peoples who might perhaps attack and defeat those who rule them.” They further reminded the doomed Melians that it was precisely out of that fear of continuous revolts across the Aegean that they had sailed into Melos to set an example to any others entertaining such dangerous ideas of opposition to the “masters of the sea.” In that context, by needs they had mastered the arts of siegecraft and boasted, “Never on a single occasion have the Athenians ever withdrawn from a siege due to the fear of any enemies,” a brag that the ironic Thucydides was sure to emphasize on the eve of the disastrous failed siege in Sicily.6

Sieges—whether Sparta’s successful attack on Plataea or Athens’ ruination of Melos—were often not explicable in a traditional strategic calculus of cost versus benefits. After all, what did the possession of Plataea do for the Spartan cause? How was Athens made more secure, wealthier, or stronger by taking Melos? The rent from the farms of the Athenian colonists who settled in the surrounding countryside after the city fell could hardly have paid the cost of the long siege. Nor would the sale of captives into slavery recover the expenses of the besiegers. Instead, the efforts to storm recalcitrant cities seemed to confer enormous psychological implications on the reputation and competence of the two powers. Letting Plataea defiantly stand apart from Thebes or Mytilene boast of its independence was seen as a contagion that could weaken the entire system of alliances that had grown up after the Persian Wars.

As the war continued, a popular Athenian strategy was to preempt problem subjects. After the costly fiasco at Potidaea—by the outbreak of the conflict the siege there was well on the way to costing the Athenian besiegers nearly 2,000 talents (something like $1 billion in contemporary American purchasing power)—the Athenian fleet learned to use the iron hand quickly lest it get bogged down in expensive sieges. The most efficacious way, in other words, to conduct a siege may have been to tear down the walls of a neutral or friendly city in advance, on mere rumors that insurrection was brewing. In the case of the Potidaeans, the Athenians had asked them to pull down their fortifications rather than doing it themselves—and as a result became mired in the most expensive siege in classical Greek history.

In contrast, during the winter of 425 the Athenians made sure that they would have no more insurrections like that on Potidaea or Mytilene. Thus, the fleet sailed into nearby Chios and forced the islanders to dismantle their newly constructed walls on promises of no reprisals—a tough strategy that seemed to have precluded most trouble there for nearly two decades. The Thebans practiced the same preemption after the battle of Delium. Given the horrendous casualties taken by small Thespiae in the Boeotian victory over the Athenians, Thebans marched into the suspicious allied city and razed its fortifications merely on rumors of pro-Athenian sympathies. The last thing the Thebans needed was another expensive siege of a nearby neutral in the manner of recalcitrant Plataea, and so it was better to tear down the walls before the Thespians knew what hit them.7

Assaulting cities is the oldest, and often the most brutal, expression of warfare. The earliest Western literature begins with the biblical siege of Jericho and the Achaeans’ attack on Troy. The most moving passages in Thucydides’ entire history of the war—the Plataeans’ pleas for mercy, the debate between Cleon and Diodotus over the fate of the Mytileneans, the Melian Dialogue, the butchery of the boys at Mycalessus, and the great siege at Syracuse—revolve around the assault on communities of men, women, and children when war came to the very doorstep of the Greek family. Indeed, Mycalessus proved horrific precisely because the Thracian mercenaries sought no real military objective other than the psychological terror of slaughtering children at school—the ancient version of the Chechnyan terrorist assault on the Russian school in Belsan during early September 2004, which shocked the modern world and confirmed Thucydides’ prognosis that his history really was a possession for all time, inasmuch as human nature, as he saw, has remained constant across time and space.

There is something surrealistic about storming a city. Sieges are final, ultimate verdicts about not merely the fate of soldiers but of a very people. Nothing is more chilling, for example, than the final hours of Constantinople—10,000 people huddled under the dome of St. Sophia, praying in vain for the angel of deliverance on the early afternoon of May, 29, 1453, as the sultan’s shock troops burst in to end for good the thousand-year culture of Byzantium. In sieges, women and old men fight from the walls. Ad hoc genius is manifested in countermeasures—history’s array of missiles, flame, cranes, and flying roof tiles—as the fate of thousands sometimes depends solely on their own collective intelligence and resolve. In the age of bombers, whose aerial weapons can make walls superfluous, sieges might seem a thing of the past, until one recalls that Leningrad and Stalingrad were two of the greatest and most costly sieges of the ages.

Sieges also reflect a breakdown in the ability of soldiers to conduct war or, rather, a failure of one side to offer resistance in the field and thereby to keep the killing far distant from civilians and their homes. True, there are so-called statutes of war; at least there were in the quieter times before the escalating violence of the Peloponnesian War. The “laws of the Greeks,” for example, assumed that upon the arrival of the enemy, besieged civilians in the ancient world would usually be offered free passage out of their city, with the acknowledgment that they must leave behind their property, their homes, and indeed their very existences. Upon their refusal to submit, all bets were off, as if it suddenly became a moral act to kill adult males and enslave their womenfolk because they either were not willing at the outset to give up or in the end could not protect all that they had held dear.

What was the moral calculus in the mind of the defenders? They had only four options once the enemy ringed their city: surrender, resistance from the walls, counterattack with sorties, or escape. The Plataeans adopted all four strategies at different times as their strength waxed and waned. During the initial Theban attack, the Plataeans rushed out and killed the intruders. Then they refused terms for some four years. Half of the garrison broke out at night and escaped. The rest finally capitulated and were either executed or enslaved.

What, then, was the degree of culpability of civilians inside the walls for their own fates? If they did not actively fight on the ramparts, were they therefore considered noncombatants, and thus to be spared after capitulation or simply executed by their peers as traitors as long as the walls held firm? Was there a moral difference between supplying food for the defenders and actually fighting from the parapets? Was it treason to offer no resistance, and did such noninvolvement mean anything anyway once enemy soldiers poured into the streets? Being besieged often had an ostensible effect of unifying the population for better or for worse; since the victor might well apply collective punishment to the defeated, most inside the walls grasped that he must be resisted at all costs. For all the bickering at Athens, both Pericles and his successors were able to keep the population together as they watched ravagers from the walls, battled plague, and put up with overcrowding.

The ethical questions do not end there. Was a defending army morally culpable should it retreat back to its civilian base, as if deliberately to draw non-combatants into a war that it could not win on the field of battle? Or was it wise to shepherd soldiers inside ramparts rather than have them perish against overwhelming odds on the battlefield and so leave their cities defenseless, when instead they might otherwise have crafted a viable defense from the walls?

The Greeks were aware of all these contradictions and ambiguities, and assumed that there was rarely political unity even before they arrived at a city, and even less once the enemy’s counterwalls rose and the pressure of hunger and disease raised tensions. Well before the Peloponnesian War armies had starved out towns and enslaved their citizens. Cities throughout the Greek world—Carystos (474), on the island of Euboea; Naxos (470), out in the Aegean; Mycenae (468), in the Argolid; the Aegean island of Thasos (465); the Boeotian town of Chaeronea (447); and Samos (440), off the coast of Ionia—that chose to resist the besiegers usually had their populations sold into slavery upon capitulation. On the very eve of the war the Corcyraeans had stormed Epidamnus, sold some of the population, and kept others as hostages—but had not executed the citizenry.8

Lining up and murdering the surrendered adult Greek male population was still rare before the Peloponnesian War, and such slaughter became habitual only after the siege of Plataea. Then a discernible pattern emerged: free exit without one’s property was offered to the besieged before the fighting started. After that window of choice closed, it was assumed that all guarantees were off, and death and enslavement loomed respectively for captured men and women. The fate of the vanquished, in short, belonged entirely to the victors—or as the dry, empirical Aristotle put it, “The law is a sort of pact under which the things conquered in war are said to belong to their conquerors.” The playwright Euripides, who reflected contemporary events in the reworking of myths and produced his Hecuba in 425—two years after the brutal Athenian putdown of Mytilene—has Hecuba relate to the assembled Athenian audience the wretched fate of the defeated Trojan royal house: Hecuba enslaved, her daughter Polyxena sacrificed, Cassandra carried off as booty, Polydorus murdered, all following the death in battle of her sons Hector and Paris, and the execution of her husband, Priam.

“Look at me and examine carefully the evils I endure,” Hecuba laments of her city’s capture and her own enslavement. “I was once a ruler, but now am your slave. Once I had good sons, now I am old and childless. I am cityless, alone, the most wretched of mortals.” Those in the audience who heard that were thinking of the poor Greeks of their own times, not mythical Trojans.9

Late in the war, as the tide of the conflict turned in their favor, Spartan generals sometimes announced that Peloponnesians did not believe in enslaving other Greeks. Yet such professed magnanimity was rarely intended to include Athenians. When Sparta sometimes released the vanquished allies of Athens, it was primarily for propaganda purposes and balanced against the singling out of Athenians for the special punishment of enslavement or death.10

Because ancient slavery was not based on the pseudoscience of genetic inferiority, all Greeks, like the royal Trojans Hecuba, Cassandra, and Andromache of myth, were in theory a city’s fall away from servitude. The great supply of slave labor in the ancient Greek world was probably obtained through the storming of cities, a tactic that is eerily concomitant with the spread of chattel slavery itself in the seventh through fifth centuries.

It is hard to tell whether the Peloponnesian War resulted in a net increase or decrease in the number of Hellenic slaves, with so many cities stormed set against the number of freed slaves enrolled in armies and navies. For example, in contrast to those who were enslaved at places like Mytilene and Melos were the helots that were freed by Brasidas, far more who fled to safe zones like Pylos, Decelea, and Chios, and thousands emancipated to fight at battles like Arginusae. In any case, W. K. Pritchett once tallied all the instances of enslavement after battles and sieges during the Peloponnesian War as recorded in our literary sources. His incomplete list of some thirty-one instances still revealed a tally of several thousand Greeks who were sold into slavery. The Peloponnesian War proved the great example of human reversal in the history of classical Greece, as hundreds of thousands of former slaves were freed even as thousands more citizens were reduced to chattel status, a fact that in part explains the social chaos of the following century, when mercenaries replaced militias and postbellum disputes over property and citizenship dominated court proceedings. Fourth-century Greece also witnessed a surge of democratic frenzy, especially at Thebes and in the Peloponnese. And at Athens especially greater subsidies were given the poorer to participate in voting—a liberalization also reflective of the vast changes in political and social life during the war, in which slaves had became free and the free slaves.11

Besides Plataea, there were a variety of other sieges in the Peloponnesian War that ended not merely in defeat but in the complete annihilation of the inhabitants. In 423 the Athenians conducted a series of attacks against three towns in northern Greece—Mende, Torone, and Scione. All had revolted from their empire. Those insurrections were particularly galling to the Athenians since an armistice calling for a temporary cessation of military operations was claimed to be in effect. But all three towns, located on key peninsulas of the Chalcidice not far from the ill-fated Potidaea, were buoyed by the success of the Spartan insurrectionist Brasidas—the so-called liberator of Hellas—and sensed a weakening in the old Athenian resolve.

Brasidas was operating far from home in hopes of bringing key cities of the Athenians’ northern empire over to the Spartans before the deadline of a general armistice took hold. In response, the Athenians eventually reduced all three and showed little mercy to the inhabitants. In the first instance, they were let into Mende by treachery, killed a number of the citizens, surrounded the rightist insurrectionists on the acropolis, and then allowed their allied democratic Mendeans to finish off the trapped revolutionaries.

Not long after, the Athenians returned in earnest to deal with the remaining two recalcitrant Chalcidian cities. They attacked Torone by land and sea, and entered the city following a retreating Spartan sortie that led them through the partially dismantled walls. All the women and children of Torone were enslaved; 700 of the males found still alive in the city were sent to Athens as hostages. At the formal acceptance of the later Peace of Nicias they were all returned.

Scione, however, was altogether a different story. The besieged city was to suffer a fate similar to Plataea’s. In summer 421, the blockaded citizens finally gave up after a brutal two-year circumvallation. This time the Athenians accorded the victims the same treatment that the Spartans had dealt the Plataeans: executing all the adult males, selling the women and children into slavery, and turning over the abandoned land and city proper to those surviving Plataeans who had lost their capital when the Spartans began the siege of 429.

Scione, like Plataea, had ceased to exist as a city. The city had temporarily joined the Spartans, and so in the Athenians’ logic it would now properly go as spoils to the Plataeans, whom the Spartans had likewise brutally expelled. Apparently, Scione was deliberately singled out to be a “paradigm” (paradeigma), inasmuch as the “Athenians wished to strike fear into those whom they suspected of planning revolts” and thus used the Scionaeans as an example to other Greeks of what could happen if a state left, or abetted those who attempted to leave, the Athenian empire.

The Athenians’ vicious policy contained a certain predictable logic in this new no-holds-barred fighting of the Peloponnesian War. Many of those citizens not involved in planning the revolt who surrendered relatively soon, like those trapped in Torone or at Mytilene earlier, were allowed to live. Cities, however, like Scione that collectively chose to hold out to the bitter end would be accorded the same treatment that the Spartans had established at the war’s beginning—a supposed sign of Athenian toughness that nevertheless made little impression on tiny Melos, which paid no heed to the fate of Scione and less than six years later met the same fate.

In the Athenian mind, the Spartans had initiated the cycle of executing surrendering citizens at the very outset of the war, and had continued that policy throughout the first decade of the fighting. In winter 424, for example, at the small outpost at Lecythus, Brasidas, who had none of the aristocratic restraint of Archidamus, had executed all the Athenian defenders who could not escape. The Spartans would go on to repeat such slaughter at Hysiae in 417 by killing all the free males of the doomed town.12

By the end of the first decade of the war the die was cast. With the reluctance of most belligerents to commit to hoplite battles, any Greek city might instead be besieged in a wider canvas of plundering, assassination, and general terror. The defenders had only one initial opportunity for surrender. Failing that, they could be executed when the city fell—a more likely certainty as the Peloponnesian War wore on. When the Athenians, desperate to end their expensive blockade of Potidaea, offered free passage out of the city to the captured populace, the assembly back home, reeling from the plague and the treacherous attack on friendly Plataea, was furious that harsher terms were not exacted. Even news that Potidaea was to be ethnically cleansed and handed over to Athenian settlers did not assuage the democracy, which probably indicted the generals for insubordination. Such “lenient” terms were never again offered to any defeated people by the Athenian assembly during the long course of the war to follow. So the engine of Athenian severity—whether on Mytilene or Melos—was driven not by rogue generals but, rather, by a majority vote of Athenian citizens themselves.13

Still, it was one thing to target insurrectionists such as those responsible for the revolts in Mytilene or Mende, quite another to kill every citizen who chose to resist and then obliterate all traces of an entire people’s existence through razing their walls and resettlement with foreign interlopers. At Plataea and Lecythus the Spartans not only executed the garrison but demolished the city itself and consecrated the ground to the gods, a slightly less utilitarian policy than that of the Athenians, who preferred to erase captured cities but give the ground over to their own settlers.

About six months after the Spartans had marched into Argos to raze the democratic faction’s incipient long walls and had stormed nearby Hysiae and butchered all the inhabitants, an Athenian fleet with 38 ships, equipped with a force of hoplites and archers numbering almost 3,500, sailed into the harbor of the tiny Aegean island of Melos. Even in summer 416, some fifteen years after the war began, the Melians remained an autonomous and quasi-neutral Dorian island city-state that for a decade and a half had astutely avoided taking sides in the fighting, although perhaps they were subjected to occasional Athenian exactions. The Athenians had earlier failed to take the island during the Archidamian War. Through a false reading of recent history, the Melians apparently thought they were more or less safe.

Yet to the Athenians there was a growing feeling that leniency toward neutrals was not appreciated but, rather, seen as evidence of their own weakness to be exploited. In their minds there was a certain logic that had led them to Melos: while the Spartans had butchered neutral Plataeans and assorted Greeks at Hysiae, the Athenians’ own past generosity had led only to further rebellion. Allowing the captured Potidaeans to leave with their lives and money perhaps explained in part the revolt at Mytilene (427), a duplicitous subject state that opportunistically reckoned that Athens was weakened by the plague and would at least give moderate terms for the captured if its own rebellion failed.

The Athenians were now determined that the next siege would lead to the death of every captured male, not the sparing of either all or some, as had happened respectively in Potidaea and Mytilene. It may have been in the long term a counterproductive strategy, since many sieges depended on developing treachery from within, an impulse harder to encourage if the besieged thought they were all going to die indiscriminately. Scione had not convinced cities that opposition to the Athenians was synonymous with obliteration. Yet upon landing at Melos, the Athenian generals Cleomedes and Tisias immediately sent envoys to demand that the Melians either join the Athenian empire or perish, willing to do to them what their Spartan friends had done to the poor garrison at Hysiae. The Melians refused to let the Athenians address the popular assembly, lest the Melian poor find the offers of inclusion under the auspices of a democratic Athenian empire seductive to their own landless citizens. The dialogue as reported by Thucydides that followed between the Athenian envoys and the Melian elite, a magisterial exploration of moral right versus realpolitik, is one of the most famous passages in all of Greek literature. The once-underdog and idealist Athenians, who over sixty years earlier had saved the Greeks from the Persian horde, had forgotten their own past of fighting for ideals of independence and freedom against impossible odds.

Now as would-be conquerors like Xerxes before, the Athenians lectured the Melians about why they must accept the reality of power, give up hope (“danger’s comforter”), relinquish their freedom, and thus submit, reminding them on the eve of their own greatest defeat of the war at Syracuse that “the Athenians never once yet have withdrawn from a siege.” In Thucydides’ hands, Melos comes after the Spartans had butchered the besieged at Hysiae, and yet right before the Athenian disaster to come at Syracuse, as the tragedy of the Peloponnesian War saw an endless cycle of violence and counterviolence, of bold conquerors unknowingly lecturing about their own fate shortly to come.

When the Athenian envoys were ready to depart after the fruitless conversation, they scoffed at the naïveté of the idealist Melians, who looked to hope rather than the formidable Athenian fleet in their harbor:

Well, you alone, as it seems to us, judging from these resolutions, regard what is future as more certain than what is before your eyes, and what is out of sight, in your eagerness, as already coming to pass; and as you have staked most on, and trusted most in, the Spartans, your fortune, and your hopes, so will you most completely be deceived.

In their customary manner—by 416 the Athenians had starved out at least six other city-states since the war had started—the besiegers walled off Melos, left a garrison, and sailed home. Although the Melians were able to mount some successful sorties to bring in more food and pick off some of the occupying garrison, for the most part they were completely locked inside their city. About six months after the beginning of the siege, the Athenians sent back additional troops to tighten up the blockade and ensure the promised capitulation through starvation. Thucydides notes that some Melians may have allowed the Athenians inside through treachery, suggesting a democratic cabal that was never given an opportunity to argue for inclusion in the Athenian empire and sought to save their own lives by stealthy assistance. But in any case the city-state itself was doomed once it was walled off from its port and cut off from its agricultural land.

No mercy was offered. The Spartans no more came to help kindred Melos than had the Athenians earlier rushed out in force to protect Plataea. Instead, both powers concentrated their efforts on the weak and neutral defender rather than the strong and bellicose attacker. Upon surrender, most adult Melian males still alive were executed. The women and children were sold as slaves. Thucydides does not provide exact numbers of those killed or enslaved on Melos, but the total must have been in the several hundreds. The land itself was divided up among 500 Athenian colonists. Melos, like Scione, no longer existed. Ancient and modern critics deplored the slaughter and paid no attention to the fact that the Athenian generals were not allowed to present their offers directly to the Melian people, or that Melos was probably not as neutral as its oligarchic officials professed. Thus even the great defender of Athens, George Grote, once lamented, “Taking the proceedings of the Athenians towards Melos from the beginning to the end, they form one of the grossest and most inexcusable pieces of cruelty combined with injustice which Grecian history presents to us.”14

One holocaust was one thing; a series of them finally made a profound impression on the Greeks. Again, after the killing of over 1,000 ringleaders of the Mytilene revolt, Euripides in his nearly contemporary Hecuba makes the heroine Hecuba curse the “murder vote” of the Achaean assembly that has brought an unwarranted death sentence to her daughter Polyxena. The tragedian offers a thinly veiled allusion to Cleon, “the honey-tongued,” and the demagogues who swayed the mercurial contemporary Athenian assembly through a “clever trick” (sophisma) first to kill all, then, after reconsidering, to kill some of the Mytilene hostages: “A cursed race all you who seek honor through demagoguery. May not you be known to me, you who think nothing of harming your friends—if only you might say something pleasing to the mob.”

But in Euripides’ mind, what happened at Melos over a decade later was far worse. In his Trojan Women, performed during the spring after the Melian siege, he chronicled the horror that arises when the walls of a city fall and the attackers give no quarter. As he once more reworked the myth of Troy’s fall into contemporary butchery, Euripides also predicted the Athenians’ own disaster to come in Sicily even as they began to make preparations to sail: “Foolish is he who levels cities, temples, tombs, and the sanctuaries of the dead; as he sows destruction, so later he himself perishes.”

Four years later, in his Phoenician Women, Euripides presented a lengthy description—“corpses heaped on top of corpses”—of the terror of being besieged by an unforgiving enemy. No doubt his long account of “a wretched city that has become utterly ruined” was in part a reaction to the Athenian string of slaughtering at Mytilene, Melos, and Mycalessus and its own disaster on Sicily. In his Hecuba, Andromache, and Trojan Women, Euripides chose to portray conquering Greeks as brutal and rapacious, and their Trojan victims as sensitive explicators of what servitude was like for the weak and vulnerable when their city fell.15

When the Spartans were on their way to sail into the Piraeus after their naval victory at Aegospotami (405), to end the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians themselves were gripped with the terror of nemesis. As the historian Xenophon put it, the Athenians had butchered so many innocent civilian Greeks at places like Scione, Torone, and Melos that they surely expected that the Spartans would do to them what they had done to other helpless and trapped garrisons. Had the Athenians won, the Spartans would have been equally afraid, remembering their own massacre of the free males of Lecythus and Hysiae, or Lysander’s enslavement of the entire community of Cedreae in southern Asia Minor.16

Less than three years after the slaughter of the Melians, in summer 413 the Athenians unleashed some Thracian mercenaries under the leadership of the Athenian general Diitrephes. These light-armed skirmishers had arrived too late to join the relief armada that had set out for Sicily under Demosthenes. To recover some of their investment, the Athenians sought to use the Thracians along the nearby Boeotian coast to plunder and ravage. For a money-strapped Athens it was inconceivable to allow 1,300 mercenaries paid at a drachma a day—an aggregate outlay of 40,000 drachmas per month, or about the capital to maintain at least six triremes—to remain idle. Moreover, Delium had proved that it was impossible to defeat the Boeotians in pitched battle, and perhaps the only way to pay them back for their plundering of Attica and recent help to Syracuse was to conduct raids of terror.

Diitrephes went ashore near the small Boeotian town of Mycalessus, which, unfortunately, as an inland member of the Boeotian Confederacy never expected a sudden attack from seaborne outsiders. Its gates were open and much of its walls were in disrepair. Thucydides makes it a point to comment on the lack of good ramparts. In part he wants to explain the anomaly of an attacking force entering a city in the interior of well-guarded Boeotia so easily. Thus, the rapidly moving Thracians almost immediately broke through the dilapidated circuit. After looting the temples and shrines they began to cut down anything that moved:

They butchered the inhabitants, sparing neither youth nor age but killing all they fell in with, one after the other, children and women, and even beasts of burden, and whatever other living creatures they saw; the Thracian people, like the bloodiest of the barbarians, being ever most murderous when it has nothing to fear. Everywhere confusion reigned and death in all its shapes; and in particular they attacked a boys’ school, the largest that there was in the place, into which the children had just gone, and massacred them all.17

Athenian ships and an Athenian general, it should be remembered, had ferried the Thracians to Mycalessus. The Athenian assembly had paid the Thracians as hired terrorists to do as much damage as possible. The Athenians were nearly as guilty of the mini-holocaust as if they had accompanied the Thracians into the doomed schoolhouse. If the war had started off with the barbarous notion that besieged citizens received only one chance to surrender and walk out alive before the walls of circumvallation ringed their city, by its third decade Greeks sometimes went beyond even these tough protocols, assuming they could burst into a city without warning, loot, and kill at random horses, oxen, dogs, and anything else that breathed.

What was life like trapped inside the usually small circuits of blockaded city-states? In the case of Athens in 430, plague quickly broke out and the population was reduced to stealing funeral biers. At Potidaea the next year the poor city folk eventually ate the dead before surrendering their exhausted city-state. Cannibalism perhaps cannot be ruled out in any of the other sieges as well. Fighting among the garrison troops was common, both over food and the decision to endure or submit. Thucydides took a keen interest in the utter depravity of such mass killing. He records at length the debate over the fate of the captured at Plataea, and the preliminary discussion to the Melian siege. The flavor of these conversations resembles the show trials of the Stalinist era, as the powerful besiegers offer pretexts of inquiry and law as explanation for preset decisions to execute the innocent and weak.18

Again, how many died in these ghastly sieges of the Peloponnesian War? There are no precise numbers, but it is likely that tens of thousands perished. The few figures that survive add up quickly: 1,050 Athenians lost taking Potidaea, with no exact figures of how many Potidaeans perished inside the walls; over 1,000 executed at Mytilene; about 45,000 Athenians and allies who did not return from the siege at Syracuse, along with an untold number of Sicilians, who were to be besieged not much later by the Carthaginians. Sources most often tally the Athenian losses but forget, perhaps, that as many Sicilians perished as well. Thousands more on both sides perished at Torone, Scione, Melos, and Mycalessus.

If one includes the execution of prisoners taken from captured ships, there were over twenty occasions in the Peloponnesian War when captured seamen or townspeople were summarily executed en masse. A recitation of such barbarity is salutary, if only to remind us just how frequent the killing became. Note especially the single year 427, when civilians were being simultaneously executed far to the west on Corcyra, on the mainland at Plataea, in the Aegean at Mytilene, and in Asia Minor by the Spartan admiral Alcidas.

Plataeans killed all Theban hostages (431). Peloponnesians did away with all Athenians found in ships off the Peloponnese (430). Alcidas slaughtered captured Athenians (427). Plataeans and Athenians were eliminated upon surrender of Plataea (427). The Athenians executed 1,000 Mytileneans (427). Corcyraean oligarchs were executed (427). Two thousand helots were rounded up and killed (424). Aeginetans were captured at Thyrea (424). Megarian oligarchs executed democrats (424). Brasidas butchered all who could not escape at Lecythus (424). Spartans killed citizens of Hysiae. Mende was sacked (423) and Melos destroyed (416). Messanians were killed by pro-Athenian insurrectionists on Sicily (415). Even schoolboys were massacred at Mycalessus (413). The Athenians were surrounded and butchered at the Assinarus River and the survivors left to die in the quarries of Syracuse (413). Samian democrats murdered oligarchs (412); in turn, Chian oligarchs slaughtered democratic Chians (412). Lysander executed Athenians after Aegospotami (404). In addition, there were another 20,000 Greek soldiers who are recorded in our sources as taken prisoner and sold into slavery. Given these atrocities and the toll of the plague, in the sense of who died and how, the term “Peloponnesian War” appears a misnomer. A far better name might be “The Thirty Years Slaughter.”19

In an obscure fourth-century military treatise about protecting poleis from besieging armies and intriguers within the walls, a shadowy Greek author, Aeneas Tacticus, who may have been a contemporary Arcadian general, reviewed the intrinsic drama of the siege. Aeneas points out that should the besieged citizenry survive, they thereby send a powerful message to the enemies not to try such a foolish attack in the future. On the other hand, should a city fall, it presaged a fate far beyond that of a defeated army alone: “But if the defenders fail in their efforts to meet the danger, then there is not one hope of safety left.”20

The word for siege or siegecraft in Greek was poliorkia (hence the term “poliorcetics,” or “fencing in the polis”). Although there was an advanced science of taking cities by 431 involving rams, mounds, and fire weapons, walls themselves remained mostly unassailable, as they grew taller and thicker well beyond the old dimensions of ten to twelve feet in height and three to six feet wide, common before the mid-fifth century. The spread of ashlar blocks and regular courses of limestone, replacing mud bricks, rubble, and irregularly shaped stones, throughout the war widened the advantages of defense over offense even further. So there is yet another paradox about the besieging of cities in the Peloponnesian War, one that tells us a great deal about the overall nature of Greek society and culture: almost every assaulted city-state eventually capitulated, and yet almost none of them fell through storming the walls.

Instead, in a world where the art of defensive fortifications had far outstripped the science of offensive siegecraft, city-states like Plataea, Potidaea, Mytilene, Scione, and Melos were starved out only after months, or even years, of systematic circumvallation. The sieges were sometimes accelerated through treachery, mostly in the form of partisans opening the gates at night. Even the supposed experts, the Athenians, did not know all that much about attacking walls and towers directly, smashing through stone foundations, or battering down wooden gates.

Scaling a wall was not as simple as it sounds. Many city ramparts were twenty to thirty feet high. Ladders by necessity were tall, their height calibrated by counting the wall’s stone or brick courses, and thus flimsy. All were easy for defenders to toss back, especially if assault troops were heavy hoplites perched on rungs in the air with sixty to seventy pounds of equipment. No army on either side yet knew how to craft wheeled siege towers with artillery and hinged boarding ramps that might provide a bridge over the fortifications—engines that would become ubiquitous only a century later, during the siege craze among the successors of Alexander the Great. The Athenians’ clumsy attempts to build a primitive tower at Lecythus ended with its collapse.21

The last chance to breach the walls was to follow a beaten army inside the walls before the gates could be shut. Even battering rams—the Athenians purportedly first fashioned them, along with protective sheds, or “tortoises,” at the prewar siege of rebellious Samos in 440—could not smash through reinforced wooden gates, at least not quickly enough to save the crews handling the ram from being picked off by stone- and missile-throwing defenders atop the walls. Primitive siege engines (mêchanai) were used not only by the Spartans at Plataea but also by the Athenians at Potidaea (“every kind of engine used in sieges”), and later in small skirmishes at Eresus and on Sicily. In all cases, such machines, probably no more than timber tipped with bronze on wheels, proved a failure, the crews sometimes wearing themselves out in vain efforts to batter down the fortifications. On other occasions they were vulnerable to capture or torching by counterassaults.22

Why was this so? Rarely were the approaches to ancient cities on flat ground. Instead, most often the targeted gates were on inclines. It was nearly impossible for crews to push ponderous rams over uphill rocky ground while under assault from the walls. A better solution was to knock the parapets down. But catapults and other sorts of artillery were not invented until after the Peloponnesian War.