Written in July 1850 (at Tocqueville)

CHAPTER 1

[Origin and character of these recollections.—General features of the era prior to the revolution of 1848.—Precursors of that revolution.]

June 1850.

Estranged for the time being from the theater of affairs and unable, on account of the precarious state of my health, even to engage in sustained study, I am reduced, in the midst of my solitude, to reflecting for a moment on myself, or, rather, on recent events in which I played a part as actor or witness. The best use I can make of my leisure, I think, is to retrace those events, describe the men I saw take part in them, and thus, if I can, fix and engrave on my memory the vague features that define the imprecise physiognomy of my time.

In taking this decision I have made another to which I will adhere no less faithfully: these recollections will be a form of intellectual relaxation and not a work of literature. I write them for myself alone. This text will be a mirror in which I shall enjoy looking at myself and my contemporaries, not a painting intended for public viewing. My best friends will know nothing of it. My only purpose in writing it is to secure for myself a solitary pleasure, the pleasure of contemplating in solitude a true portrait of human society; to discern man’s virtues and vices as they really are, to understand his nature, and to judge it. I wish to preserve the freedom to portray without flattery both myself and my contemporaries, in total independence. I wish to lay bare the secret motives that led me and my colleagues and others to act as we did, and when I have understood those motives, to describe them. In short, because I wish to express my recollections honestly, they must remain entirely secret.

I do not intend to delve further into the past than the revolution of 1848 or to pursue the story beyond my exit from the ministry on October 30, 1849. Only between these two dates is there any grandeur to the events I wish to describe, and only then did my position afford me a clear view of them.

I lived, though somewhat aloof, in the parliamentary milieu of the last years of the July Monarchy, yet I would find it difficult to recount the events of that time, which remain so close and yet so blurred in my memory. I lose the thread of my recollections in the labyrinth of petty incidents, petty ideas, petty passions, idiosyncratic views, and contradictory projects in which the public figures of that time wasted their lives. Only the general aspect of the era sticks in my mind: because I often contemplated it with curiosity mingled with fear, I clearly perceived its characteristic features.

When viewed in perspective and as a whole, our history from 1789 to 1830 struck me as a pitched battle that raged for forty-one years between the Ancien Régime, with its traditions, memories, and hopes, epitomized by the aristocracy, and the new France, led by the middle class. Eighteen thirty, it seemed to me, ended this first period of our revolutions, or, rather, our revolution, for there was only one—it was always the same, despite the vagaries of fortune and individuals, this revolution whose beginnings our parents witnessed and whose end in all likelihood we will not live to see. All that remained of the Ancien Régime was destroyed forever. By 1830 the triumph of the middle class was definitive, and so complete that all political power, all franchises, all prerogatives, and the entire government were confined and somehow squeezed within the narrow limits of the bourgeoisie, legally excluding everything below it and in fact all that had once stood above. The bourgeoisie became not only society’s sole ruler but also its financier. It occupied all places, vastly increased the number of places to be occupied, and became accustomed to living almost as much off the public exchequer as off the fruits of its own industry.

No sooner had this great event taken place than political passions suddenly cooled, events were drained of all significance, and the nation’s wealth grew rapidly. The particular spirit of the middle class became the general spirit of the government. The middle-class spirit dominated foreign policy as well as domestic affairs; it was an active, industrious spirit, often dishonest, generally circumspect, occasionally bold for reasons of vanity and egotism, timid by temperament, moderate in all things except the taste for well-being, and mediocre, a spirit that, if mixed with that of the people or the aristocracy, can work wonders but that alone will never yield anything but a government without virtue and without greatness. Master of everything as no aristocracy ever was or perhaps ever will be, the middle class, which should be called the governmental class, immured in its power and before long in its selfishness, made government resemble private industry. Each member of government dwelt on public affairs only insofar as they could be turned to private profit, readily forgetting the people while reveling in his own private prosperity.

Posterity, which sees only glaring crimes and usually overlooks vices, may never know the extent to which government then came to resemble an industrial firm, in which every operation is carried out with an eye to the profit stockholders may derive from it. These vices stemmed from the natural instincts of the ruling class, its absolute power, and the enervation and even corruption of the age. King Louis-Philippe did much to encourage them. He was the accident that made the disease fatal.

Although this prince sprang from the noblest race in Europe, whose hereditary pride he concealed in the depths of his soul, and surely looked upon no other man as his equal, he nevertheless possessed most of the qualities and defects more commonly associated with the subaltern ranks of society. He had proper manners and wanted those around him to have them as well. He was disciplined in his conduct, simple in his habits, and moderate in his tastes. By nature he was a friend of the law and an enemy of all excess, temperate in his actions if not his desires. He was humane without being sentimental, greedy and mild. He had no raging passions or ruinous weaknesses, no glaring vices, and of kingly virtues only one: courage. He was extremely polite but without discernment or grandeur—the politeness of a merchant rather than of a prince. He had little taste for literature or the arts but loved industry with a passion. His memory was prodigious and apt to retain the smallest details with tenacity. His conversation—prolix, diffuse, original, vulgar, anecdotal, replete with small facts, savory and sensible—yielded all the satisfaction one can find in the pleasures of the intellect when delicacy and nobility are wanting. His mind was distinguished but limited and hampered by his soul’s lack of elevation and breadth. Enlightened, subtle, supple, and tenacious, fixed exclusively on the utilitarian and filled with such profound contempt for truth and such complete disbelief in virtue that his intelligence was consequently dimmed, he not only failed to see the beauty that truth and honesty always exhibit but also failed to understand that they can frequently be useful. He had a profound understanding of men, but only of their vices. In religion he had the incredulity of the eighteenth century, and in politics the skepticism of the nineteenth. An unbeliever himself, he had no faith in the belief of others. He loved power and dishonest courtiers as naturally as if he had been born to the throne. His ambition, limited only by prudence, was never fully satisfied nor out of control and always remained close to the earth.

This portrait resembles any number of princes, but what distinguished Louis-Philippe was the analogy, or rather the kinship and consanguinity, that existed between his flaws and those of his era, which made him an attractive as well as a singularly dangerous and corrupting prince for his contemporaries and, in particular, for the class in power. Had he headed an aristocracy, he might have exerted a beneficial influence. As leader of the bourgeoisie, he encouraged its natural bent, pushing it in a direction in which it was all too inclined to go already. His vices wedded its vices, and this union, from which he initially drew strength, ultimately demoralized his partner and led both to ruin.

Although I was never admitted to this prince’s councils, I was fairly frequently in his presence. The last time I saw him at close quarters was shortly before the catastrophe of February. I was then director of the Académie française and had to discuss a matter pertaining to that body with the king. After dealing with the issue that had brought me, I was about to take my leave, but the king detained me, sat down, invited me to sit as well, and addressed me familiarly: “Since you are here, Monsieur de Tocqueville, let’s chat. I’d like to hear you speak about America.” I knew him well enough to know that this meant “I am going to speak about America.” He did in fact speak, interestingly and at considerable length, during which time I had neither the opportunity nor the desire to utter a word, because I was truly interested in what he had to say. He described places as if he beheld them before his eyes. He recalled the distinguished men he had met forty years earlier as if he had left them the day before. He mentioned their first and last names and their ages at the time and recounted their stories and ancestry and offspring with marvelous precision and endless details, without being boring. Then, without pausing for breath, he turned from America to Europe and discussed our foreign and domestic affairs in terms I thought incredibly intemperate, since I had no right to his confidence; he said terrible things about the emperor of Russia, whom he called Monsieur Nicolas, characterized Lord Palmerston in passing as a rascal, and concluded with a lengthy disquisition on the recent Spanish marriages and the embarrassment these had caused him in England.1 “The queen is very put out with me,” he said, “and quite annoyed, but none of their whining will stop me from driving my own carriage.” Although this expression dated from the Ancien Régime, I doubted that Louis XIV ever used it after agreeing to the Spanish succession. Furthermore, I think Louis-Philippe was mistaken and, as he might have put it, the Spanish marriages played an important part in overturning his carriage.

After three-quarters of an hour, the king rose, thanked me for the pleasure our conversation had given him (though I had not spoken four words), and bid me farewell, clearly delighted with me as we usually are delighted with anyone in whose presence we think we have shined. That was the last time I spoke with him.

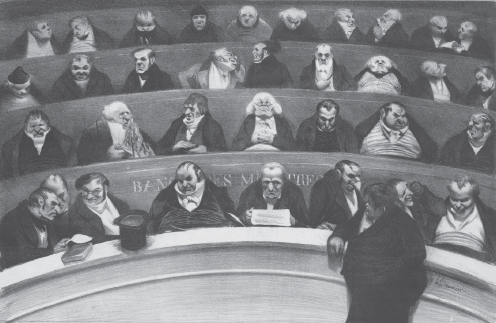

“Le ventre législatif” [the legislative belly], Chamber of Deputies, by Honoré Daumier, 1833

When addressing the most important state bodies, this prince really did improvise his responses, even in the most critical moments. In such circumstances he spoke as volubly as in conversation, but with less felicity and fewer barbs. Usually, a deluge of commonplaces was delivered with gestures as insincere as they were exaggerated and considerable effort to appear moved, with abundant beating of the breast. In such moments he often became obscure, because he plunged ahead boldly, with head lowered, as it were, embarking on long sentences whose extent he did not anticipate and whose end he could not see and from which he exited abruptly and violently, emptying his words of meaning and leaving his thought unfinished. In general, his style on formal occasions recalled the sentimental jargon of the late eighteenth century, reproduced with ready fluency and blatant inaccuracy: Jean-Jacques2 retouched by a (pedantic) nineteenth-century scullery maid. I am reminded of the day when the Chamber of Deputies visited the Tuileries and I found myself standing in front, quite exposed. I almost caused a scandal by bursting out laughing when Rémusat, my colleague in both the Académie and the legislature, maliciously whispered in my ear, in a grave and melancholy tone while the king was speaking, this exquisite judgment: “Right now, the good citizen is obliged to feel agreeably moved, but the academician is in agony.”

In a political world so structured and led, what was most lacking, especially at the end, was political life itself. Within the limits established by the constitution, there was little chance that political life would ever see the light or survive for long if it did. The old aristocracy was vanquished, the people were excluded. Since all affairs were dealt with by members of a single class in accordance with the interests and views of that class, there was no battlefield on which major parties could clash. The singular homogeneity of positions, interests, and consequently views that prevailed in what M. Guizot called le pays légal3 deprived parliamentary debate of all novelty and reality and therefore of all true passion. I spent ten years of my life in the company of very great minds that, though perpetually agitated, never rose to the level of true passion and exhausted their perspicacity in a vain search for issues about which they could truly disagree.

Furthermore, the supremacy that Louis-Philippe acquired by capitalizing on the errors and especially the vices of his adversaries meant that to disagree too much with his thinking was to forfeit any chance of success; this reduced the differences between the parties to mere shades of opinion, and political conflict to quibbles over words. I do not know if any parliament (including the Constituent Assembly, by which I mean the authentic one, that of 1789) ever assembled a more varied and brilliant array of talents than ours in the final years of the July Monarchy. I can assert, however, that those great orators repeatedly bored one another, and worse yet, bored the entire nation. France gradually came to think of battles in the Chambers as intellectual jousts rather than serious debates, and of what divided the various parliamentary parties—majority, center left, and dynastic opposition—as quarrels among children of a single family bent on cheating one another out of their share of an inheritance. The accidental discovery of a few striking instances of corruption hinted at hidden corruption everywhere, persuading the nation that the whole governing class was corrupt and thus fostering a quiet contempt that the people in power took for trusting and satisfied submission.

The country was then divided into two parts, or, rather, two unequal realms. In the upper part, which by design was supposed to encompass all political activity, lethargy, impotence, immobility, and boredom prevailed. In the lower part, however, political life had begun to manifest itself in the form of sporadic fevers, whose symptoms were apparent to any attentive observer.

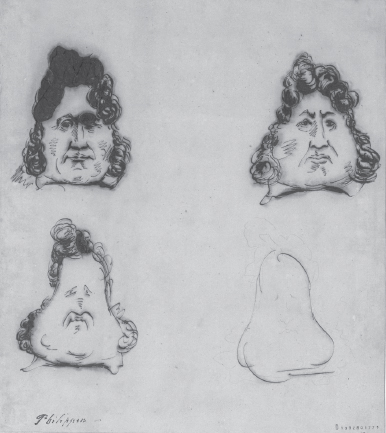

King-Louis Philippe’s metamorphosis into a pear, by Charles Philipon, 1830—first sketch of a theme that Daumier, who worked closely with Philipon, developed

I was one of those observers, and although I was far from imagining that the catastrophe was so imminent or that it would be as terrible as it was, I felt a growing anxiety and became increasingly convinced that we were headed toward a new revolution. This represented a significant change in my thinking, because the universal apathy and abjection that had followed the revolution of July had for a long time led me to believe that I was destined to spend my life in a tranquil but listless society. Anyone who looked at how the country was governed strictly as an insider would have been convinced of this. The machinery of liberty was manipulated to give great power to the monarchy, power almost absolute and close to despotic, yet effortlessly achieved thanks to the workings of a carefully contrived and well-oiled machine. Quite proud of the advantage he derived from this ingenious mechanism, King Louis-Philippe was convinced that as long as he refrained from interfering with this admirable instrument, as Louis XVIII had done, and allowed it to operate according to its own rules, he would remain safe from any danger. His sole mission was to keep the machinery in running order and to use it as he saw fit, oblivious of the society on which it had been erected. In this he resembled the man who refused to believe that his house had been set ablaze as long as its key remained in his pocket. Since I did not share his interests or concerns, I was able to penetrate the institutional mechanisms and the welter of insignificant daily facts to consider the state of the country’s mores and opinions. I clearly perceived any number of signs that generally herald the approach of revolution, and I began to believe that in 1830 I had mistaken the end of an act for the end of the play.

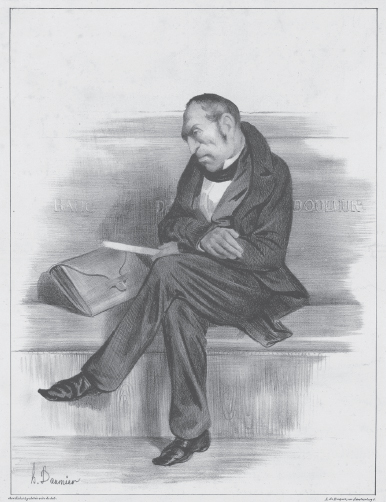

Francois Guizot, by Honoré Daumier, 1833

A brief text I wrote at the time but never published, along with a speech I gave at the beginning of 1848, attests to my concerns.

Several of my parliamentary friends met in October 1847 for the purpose of deciding what course to take in the upcoming legislative session. It was agreed that we would publish a program in the form of a manifesto, and I was assigned to write the text. Later, the idea of publishing it was abandoned, but I had already written the document as requested. Having come across it among my papers, I offer the following excerpt. After describing the lethargic state of parliament, I added:

. . . A time will come when the country again finds itself divided between two great parties. The French Revolution, which abolished all privileges and nullified all exclusive rights, nevertheless allowed one to remain: the right of property. Owners of property should be under no illusion about the strength of their position, however, nor should they imagine that the right of property is an impregnable rampart just because it has never yet been breached, for our era is like no other. When the right of property was merely the fons et origo4 of many other rights, it was easily defended, or, rather, it was not attacked. It then stood as society’s outer wall, and all other rights served as defensive outposts. No blow ever struck the wall itself. Today, however, the right of property is merely the last vestige of a destroyed aristocratic world, and it stands alone, an isolated privilege in the midst of a leveled society, unprotected by numerous other more contestable and hated rights, and is therefore in greater peril. Now it must absorb alone, daily, direct and constant shocks of democratic opinion. . . .

. . . Political struggle will soon pit those who own property against those who do not. Property will be the great battlefield, and the main issues of politics will revolve around the extent of the changes to be made to the rights of property owners. We will once again see great public agitation and great parties.

How can anyone fail to be struck by the premonitory signs of this future? Does anyone believe that it is by chance, an effect of a passing caprice of the human mind, that all around us singular doctrines are emerging, with diverse names but all sharing one primary characteristic, namely, the negation of the right of property, the exercise of which all seek to limit, diminish, or weaken? Who does not recognize the latest symptom of that old democratic malady whose crisis may be at hand?

I was even more explicit and more insistent in a speech I delivered to the Chamber of Deputies on January 29, 1848, which was published in Le Moniteur on the 30th.

Here are the main passages:

. . . Some say there is no peril because there are no riots. Some say that since no material disorder has yet disturbed the surface of society, revolution is a long way off.

If I may say so, gentlemen, I think you are mistaken. Although there is indeed no visible disorder, disorder has penetrated deeply into people’s minds. Look at what is happening among the working classes, which I admit are quiet for the moment. They are not now tormented by explicit political passions to the same degree as in the past. But do you not see that their passions, once political, have become social? Do you not see that opinions and ideas are slowly spreading among them that will someday overturn not only laws, ministries, and governments but society itself, by undermining the base on which it now rests? Are you not listening to what is being said among them every day? Can you not hear the endless refrain, that those above them are incapable and unworthy of governing; that the present division of the goods of this world is unjust; and that the basis of property is unfair? Do you not think that when such opinions take root and spread nearly everywhere, striking deep roots in the masses, they must sooner or later—I know not when or how—issue in the most redoubtable of revolutions?

My deepest conviction, gentlemen, is this: I believe we are presently sleeping on a volcano. I am deeply convinced of this. . . .

. . . As I was saying, this evil will sooner or later lead—I know not how or by what means—to the most serious revolutions in this country. Of this you can be sure.

When I study other times, other eras, and other nations in search of the true cause of the governing class’s downfall, I take note of this or that event, this or that man, this or that accidental or superficial cause, but believe me when I say that the real cause, the effective cause that deprives men of power, is this: that they have become unworthy of wielding it.

Think, gentlemen, of the old monarchy. It was stronger than you are, stronger by dint of its origin. It was more strongly supported than you are by ancient customs, venerable mores, and long-standing beliefs. It was stronger than you, yet it collapsed into dust. And why did it collapse? Do you think some specific accident was responsible? Do you think it was the fault of some man, or of the deficit, or of the Tennis Court Oath,5 or Lafayette, or Mirabeau? No, gentlemen. There was another cause: it was that the ruling class had become, by virtue of its indifference, its selfishness, and its vices, incapable and unworthy of governing.

That was the true cause of its downfall.

Yes, gentlemen, if it is just in every era to voice such patriotic concerns, why is it not still more just to voice them in our own time? Do you not feel, by a sort of instinctive intuition that defies analysis yet stands beyond doubt, that the ground in Europe is once again trembling? Do you not feel—how shall I put this?—a wind of revolution in the air? No one knows who or what created this wind, or where it comes from, or, believe me, whom it may carry away. Yet in these times, as public mores become increasingly degraded—the word is not too strong—you do nothing.

I speak without bitterness, indeed, I think, without partisan spirit. I attack men against whom I feel no anger. But in the end I am obliged to let my country know my deep and considered opinion. So listen well. My deep and considered opinion is that public mores are becoming degraded. It is that the degradation of public mores will lead soon, perhaps imminently, to new revolutions. Do the lives of kings hang by stouter, less fragile threads than the lives of other men? Are you certain today that tomorrow will dawn? Do you know what will happen in France a year from now, a month from now, or perhaps even tomorrow? You have no idea, but what you do know is that the storm is on the horizon and headed toward you. Will you heed this warning?

Gentleman, I beg you not to let the storm break. I do not ask, I beg. I would willingly kneel before you, so fervently do I believe that the danger is real and serious and so deeply do I believe that to point this out is not mere vain rhetoric. Yes, the danger is great! Avert it while there is still time. Take effective steps to correct the evil, not by attacking its symptoms but by going after the thing itself.

Some have spoken of changing the law. I am quite convinced that such changes are not only very useful but also necessary. Thus I believe in the usefulness of electoral reform and in the urgency of parliamentary reform. But I am not foolish enough, gentlemen, to be unaware that laws alone do not determine the fate of nations. No, great events come not from the mechanism of the law but from the spirit of the government. Keep the laws, if you wish. Although I believe you would be very wrong to do so, keep them. Even keep the men if it pleases you. I, for one, will not stand in your way. But for God’s sake, change the spirit of the government, for I repeat, that spirit is driving you into the abyss.

These somber predictions were met with insulting laughter from the majority. The opposition applauded vigorously, but for partisan reasons rather than out of conviction. The truth is that no one yet seriously believed in the danger I predicted, though the end was near. The inveterate habit that all our politicians had contracted during the lengthy parliamentary comedy—the habit of painting their feelings in lurid colors and exaggerating their ideas—made them more or less incapable of recognizing what was real and true. For years the majority insisted daily that the opposition was placing society in jeopardy, while the opposition repeated endlessly that the government’s ministers were destroying the monarchy. Both sides had so often asserted things they did not really believe that in the end they believed nothing, even when the event arrived that would prove them both right. Even my own friends believed that there was an element of rhetoric in my speech.

I recall that as I descended from the podium, Dufaure took me aside and told me, with that sort of parliamentary divination that was his sole claim to genius, “You were a success, but you would have been an even greater success if you hadn’t gone so far beyond what the Assembly feels and hadn’t tried so hard to terrify us.” Now that I am alone with my thoughts, I search my memory and wonder if I was indeed as frightened as I appeared to be, and I find that the answer is no. I recognize that the event justified me more promptly and completely than I had anticipated. No, I did not anticipate a revolution like the one we were about to witness. Who could have anticipated it? What I did anticipate more clearly than others, I think, was the general causes that were leading the July Monarchy to ruin. I did not foresee the accidents that would precipitate its downfall. Yet the days that stood between us and the catastrophe were passing rapidly.

CHAPTER 2

[Banquets—Security of the government.—Preoccupation of the leaders of the opposition.—Impeachment of ministers.]

I did not want to get involved in the agitation around the banquets. I had various reasons for refraining, some minor, others major. What I call minor reasons—and would readily call bad reasons, although they were honorable and would have been excellent in a private affair—had to do with my irritation and disgust with the character and maneuvering of the people behind that whole business. I nevertheless concede that our private feelings about individuals are a poor guide in politics. At the time, a close alliance was formed between M. Thiers and M. Barrot, and the two opposition factions, to which we in our parliamentary jargon referred as the center left and the left, actually fused. Nearly all the rigid and refractory minds so numerous in the latter party were tamed, calmed, or cowed by M. Thiers’s generous promises of offices. Indeed, I believe that for the first time M. Barrot himself was, if not exactly endorsing an argument of this sort, surprisingly engaging it. Thus, for whatever reason, the two leading figures of the opposition forged the closest possible alliance, and M. Barrot, whose strengths as well as weaknesses were invariably tinctured with traces of foolishness, did his best to secure the triumph of his ally, even at his own expense. M. Thiers had allowed him to engage in the business of the banquets. Indeed, I think M. Thiers pushed him into it while himself remaining aloof, eager for the result but reluctant to accept responsibility for such a dangerous agitation. Surrounded by his close allies, he stayed put, and silent, in Paris, while Barrot traveled all around the country for three months, delivering a lengthy speech in every town he visited. He reminded me of a beater in a hunting party, who raises a ruckus in order to drive the quarry closer to the hunter awaiting his chance to get off a good shot. I had little interest in joining the hunt. But my main reason for staying out of it was one that I often explained to those who tried to drag me off to political meetings:

For the first time in eighteen years, you’re trying to speak to the people and seeking support outside the middle class. If you fail to stir up the people, which seems to me the most likely outcome of your efforts, you will become even more odious than you already are in the eyes of the government and the middle class, the majority of which supports the government, and you will thus strengthen the power you seek to overthrow. If, on the other hand, you do stir them up, you have no more idea than I do where such agitation may lead.

As the banquet campaign wore on, the second hypothesis became, contrary to my expectation, the more likely. The leaders themselves began to feel a vague anxiety, a transient foreboding rather than a constant worry. From Beaumont, who was at that point one of the leading figures in the campaign, I learned that the agitation the banquets had stirred up throughout the country exceeded not only the hopes but also the desires of the organizers, who sought to calm things down rather than further fan the flames. Their intention was that there should be no banquet in Paris or anywhere else once the Chambers were convened. The truth is that having embarked on the wrong path, the leaders of the movement were seeking a way out. The final banquet was certainly organized against their wishes. They were compelled to sponsor it only because plans were already in place, and above all for reasons of wounded vanity. The government itself put pressure on the opposition by defying its dangerous provocation, hoping to precipitate its ruin. The opposition responded with bravado so as not to appear to retreat. Government and opposition thus goaded each other on, pushing each other toward the common abyss, which neither saw looming just ahead.

Two days before the revolution of February, I attended a gala ball at the Turkish Embassy, where I ran into Duvergier de Hauranne. I respected him and counted him a friend even though he exhibited nearly all the faults a partisan spirit can foster, yet tempered by the sort of disinterestedness and sincerity that true passion can inspire—two rare advantages nowadays, when few people feel any true passion for anything but themselves. With a familiarity authorized by our friendship, I said, “Courage, my dear friend, you are playing a dangerous game.” To which he replied bravely and without the slightest hint of fear: “It will all turn out well in the end. In any case, the risk has to be run. These are the kinds of trials that every free government has had to face.” His answer paints a vivid portrait of this resolute yet limited man—limited but quite intelligent, intelligent enough to see clearly and in detail what looms ahead yet incapable of imagining that things may change. Erudite, disinterested, ardent, bilious, and vindictive, he belonged to that learned and sectarian breed of man who bases his politics on imitation of foreign examples and historical reminiscences and who encapsulates his thinking in a single idea, which invigorates but also blinds him.

The government, moreover, was less worried than were the leaders of the opposition. A few days prior to this conversation, I had another with Duchâtel, the minister of the interior. I was on good terms with him even though I had for eight years been at war with the government of which he was one of the leaders (a little too vigorously at war, I confess, when it came to foreign policy). Indeed, my error may even have enhanced my stature in his eyes, because I think he felt a certain affection for anyone who attacked his colleague at the ministry of foreign affairs, M. Guizot. Some years earlier, M. Duchâtel and I had joined forces in a controversy over penitentiaries, and this had brought us together and in a way made us allies. Duchâtel bore little resemblance to Duvergier de Hauranne. He was as robust in personality and manners as the other was sickly, skeletal, and at times bitter and cutting. He was as skeptical as the other was fired with ardent convictions, as cheerfully detached as the other was feverishly active. Equipped with an extremely supple, astute, and subtle mind encased in a massive body, he had an admirable grasp of affairs, which he discussed superbly. With his deep knowledge of man’s darker passions, and especially of the darker passions of his own party, he was always able to take advantage of them. He was devoid of prejudice or rancor, affable, easy to approach, and always ready to oblige as long as his own interests did not get in the way. Toward other men he felt a full measure of contempt as well as kindness. In short, he was a man one could neither respect nor despise.

A few days before the catastrophe, I took M. Duchâtel aside in a corner of the conference room and told him that the government and the opposition seemed to be working hand in hand to bring things to a head in a way that could well end up hurting everyone. I asked him if he could not see a decent way out of such an unfortunate situation, some honorable deal that would allow both sides to back down. I added that my friends and I would be happy if someone showed us the way and that we would do everything we could to persuade our colleagues in the opposition. He listened to me attentively and assured me that he understood what I was saying, but I saw clearly that he did not share my view. “Things have reached the point,” he said, “that the sort of compromise you are seeking is out of the question. The government, being within its rights, cannot yield. If the opposition persists in its present course, there may well be fighting in the streets. But such fighting has long been anticipated, and if the government is indeed animated by the sinister passions some ascribe to it, it will not fear this outcome but desire it, because it is certain of victory.” He then calmly laid out in detail all the military measures that had been taken, the extent of the government’s resources, the number of troops, the stockpiles of munitions, and so on. I left convinced that the government, without exactly seeking to initiate an uprising, had no fear of one. Certain of victory, it saw the impending clash as the only remaining means of rallying its dispersed friends and confounding its adversaries.

I confess that I saw things as he did. His unfeigned air of confidence impressed me.

The only people in Paris who were really concerned at that point were the leaders of the radicals and those sufficiently close to the people and the revolutionary party to know how things stood in that quarter. I have reason to believe that most of them viewed the impending events with alarm, perhaps because their erstwhile revolutionary passions survived not as authentic passions but merely as traditions, or because they had lately become used to the positions they now held in an order they had so often condemned, or because they had doubts that the revolution would succeed, or because they knew their confederates well and were frightened of what they would owe them in case of ultimate victory. On the eve of the uprising, Mme de Lamartine called on Mme de Tocqueville in such an extraordinary state of anxiety, so aroused or perhaps even deranged by sinister thoughts, that an alarmed Mme de Tocqueville felt compelled to tell me about it that very evening.

It was a strange revolution, not the least bizarre aspect of which was the fact that the precipitating event was initiated by those whom it toppled from power and who came close to wanting it, while only those whom it would bring to power foresaw and feared it.

At this point I need to recapitulate the sequence of events so that I can match my memories to what actually occurred.

At the opening session of parliament in 1848, King Louis-Philippe, in his royal address, characterized the organizers of the banquets as men animated by blind or hostile passions. This put the monarchy at odds with more than a hundred members of the Chamber. The insult, which added anger to the ambitious passions already seething in the hearts of most of these men, deprived them of their reason. A violent debate was expected, but at first nothing happened. The early responses to the king’s speech were mild. Like two men in a rage and therefore afraid of saying or doing something stupid, the majority and the opposition initially held back.

When passion did at length erupt, it did so with unaccustomed violence. To anyone with a nose for revolution, the vehemence of the parliamentary debate already smelled of civil war.

In the heat of battle the orators of the moderate opposition were led to insist that the right to assemble in banquets was one of our most incontestable and necessary rights and that to challenge it was to trample on liberty itself and violate the Charter, failing to see that they were thus issuing a call not to argument but to arms. Meanwhile, M. Duchâtel, though usually quite adept, could not have been clumsier than he showed himself to be that day. He categorically denied the existence of a right to assemble yet failed to state clearly that the government had decided to prevent any similar demonstrations in the future. Indeed, he seemed to invite the opposition to dare to repeat the provocation so that the courts could take up the question. His colleague the minister of justice, M. Hébert, was even more maladroit, but in his case it was customary. I had long been aware that magistrates make poor politicians, but I never met a magistrate who made a worse politician than M. Hébert: on becoming a minister, he remained a prosecutor to his very marrow. He had the character of one and looked the part. Imagine a narrow, pinched weasel’s face, compressed at the temples; an angular forehead, nose, and chin; cold, penetrating eyes; taut, pinched lips; and a long quill generally held across his mouth, which from a distance looked like the bristling whiskers of a cat, and you will have before you the portrait of a man who resembled a carnivorous animal more than anyone I have ever known. Although he was neither stupid nor evil, he had a rigid mind, incapable of bending or adapting when needed, and was apt to stumble unwittingly into violence because he failed to grasp the subtleties of a situation. For M. Guizot to have sent such a speaker to the podium in such circumstances, he must have set little store by conciliation. Hébert’s language was so overheated and provocative that Barrot, beside himself and scarcely aware of what he was doing, shouted in a voice choking with rage that Charles X’s ministers Polignac and Peyronnet had never dared to express themselves in such terms. I felt a shiver down my spine as I sat listening to this man, normally so moderate and so devoted to the monarchy but at his wit’s end, evoke for the first time the awful memory of the revolution of 1830, in a way holding it up as an example and unwittingly suggesting the idea of imitating it.

The result of this heated debate was that government and opposition in effect challenged each other to a duel, to be fought at the bar of justice. It was tacitly agreed that the opposition would hold one last banquet and that the government would not prevent the meeting but would prosecute its organizers, after which the courts would decide.

Debate on the address ended, if I recall correctly, on February 12. From that moment on, the movement toward a revolution accelerated. The constitutional opposition, which for months had been prodded by the radical party, was thereafter led and controlled by the radicals—not so much by those who held seats in the Chamber of Deputies (most of whom had grown tepid and listless in the parliamentary climate) as by younger, bolder, less well-off radicals who wrote for the demagogic press. The subjugation of the moderate opposition by the revolutionary party was inevitable once their joint action was prolonged. I have noticed that in any political assembly, those who want both the means and the end always gain the upper hand in the long run over those who want one without the other. This subjugation was especially evident in two major developments that exerted an overwhelming influence on the course of events: the program for the impending banquet and the impeachment of the government’s ministers.

On February 20 nearly all the opposition newspapers published the program of the next banquet, which was a veritable proclamation calling on the entire population to stage an immense political demonstration; the schools and even the National Guard were invited to attend the ceremony as a body. It looked for all the world like an order issued by a provisional government, which was not actually formed until three days later. The government, which some of its own supporters already blamed for having tacitly authorized the banquet, felt entitled to withdraw its authorization, announcing that the meeting was officially banned and would be prevented by force.

This declaration by the government set the stage for the coming battle. I can state with confidence that, unbelievable as it may seem, the program that thus turned the banquet into an insurrection was drafted, approved, and published without the participation or knowledge of the members of parliament, who believed they were still in control of the movement they had brought into being. The program was the nocturnal effort of a group of journalists and radicals, and like the general public, the leaders of the dynastic opposition found out about it only when they read its text in the papers the next morning.

One sees the extent to which human affairs are subject to unpredictable reactions. M. Odilon Barrot, who was as critical of the banquet program as anyone, did not dare to disavow it for fear of offending men who had previously appeared to be his supporters. But when the government, frightened by publication of the program, banned the banquet, M. Barrot, faced with the prospect of civil war, retreated. He refused to take part in the dangerous meeting, yet even as he made that concession to moderate opinion, he joined the extremists in impeaching the government’s ministers. He accused them of having violated the constitution by banning the banquet and thus handed an excuse to those who were about to take up arms in defense of the violated constitution.

Meanwhile, the principal leaders of the radical party, who opposed revolution because they believed it was premature, felt obliged to distinguish themselves from their allies in the dynastic opposition by delivering highly revolutionary speeches at the banquets, thus fanning the flames of insurrection. The dynastic opposition, for its part, wanted an end to the banquets but was forced to continue down the unfortunate path of calling for them so as not to appear to retreat in the face of the government’s ban. Finally, the conservatives, most of whom believed that important concessions were necessary and desirable, were compelled by the violence of their adversaries and the passions of a few of their leaders to deny even the right to assemble in private banquets and to deprive the country of any hope of reform whatsoever.

One has to have spent long years in the whirlwind of party politics to understand the extent to which men drive one another off their intended courses, so that the direction in which the world moves is often quite different from what its movers intend, just as the movement of a kite is determined by the opposing tugs of wind and string.

CHAPTER 3

[Disturbances of February 22.—Session of February 23.—New government.—Sentiments of M. Dufaure and M. de Beaumont.]

February 22 did not strike me as an occasion for serious concern. People were already clogging the streets, but the crowd seemed to me to be made up of curious onlookers and malcontents rather than rebels; soldiers and citizens greeted one another cheerfully, and what I heard from the throng was raillery rather than shouts. One should of course be wary of such appearances. Insurrections in Paris generally begin among youngsters, who usually go about their business with the alacrity of schoolboys on vacation.

Upon returning to the Chamber, I discovered a stoic mood that scarcely concealed the myriad passions seething just below the surface. Since that morning, the Chamber was the only place in Paris where no one discussed aloud what was then on the mind of every Frenchman. There was a desultory debate about creating a bank in Bordeaux, but only the speaker at the podium and the deputy who was supposed to reply paid any attention. M. Duchâtel told me that things were going well. As he said this, he seemed at once confident and agitated, which struck me as suspect. I noticed that his neck and shoulders twitched much more than usual, and this petty detail aroused my concern more than anything else.

I learned that there had been serious trouble in several places I had not visited. Men had been killed or wounded. These kinds of incidents were not as common as they had been a few years earlier or would become a few months later; emotions were running high. I was invited to dinner that evening at the home of one of my colleagues in the opposition, M. Paulmier, a deputy from Calvados. I had some difficulty reaching his home because of the troops still patrolling the streets. I found the house in great disarray. Mme Paulmier, who was pregnant at the time and who had been frightened by a skirmish just outside her window, had gone to bed. Although the dinner was splendid, there were few diners. Of the twenty people invited, only five came. The others were prevented by either material obstacles or worries about the day’s events. It was a pensive party that sat down to a pointless repast. I reflected that we were living in strange times, in which one could never be sure that a revolution would not take place between when one ordered one’s dinner and when one sat down to eat it. Among the guests was M. Sallandrouze, the heir to the great commercial house that bears his name, who had made a fortune in the manufacture of carpets. M. Sallandrouze was one of those young conservatives with more money than honors, who from time to time gave hints of opposition, if not impertinence—mostly, I think, to make himself feel important. During the final debate on the king’s address, he had offered an amendment that would have compromised the cabinet had it been adopted. While this incident was still fresh in the minds of his colleagues, M. Sallandrouze attended a reception at the Tuileries, hoping that this time he would not go unnoticed in the crowd. Indeed, the minute the king spotted him, he hastened over and took him aside, expressing warm interest in the industry in which the young deputy had made his fortune. At first M. Sallandrouze was not surprised by this, thinking that the king, always adept at managing men, had chosen this pretext as a prelude to a discussion of more important matters. He was mistaken, however: fifteen minutes later the king abruptly moved on, not to a new topic but to a new interlocutor, leaving our man quite confused amid his wool and his rugs. Still smarting from the trick played on him, Sallandrouze began to fear that he would be only too well avenged. He told us that M. Emile Girardin had said to him the day before that “in two days’ time, the July Monarchy will be no more.” This struck us as journalistic hyperbole, and perhaps it was, but events turned it into an oracle.

The next day, February 23, I awoke to learn that the agitation in Paris, far from quieting down, had only increased. I went immediately to the Chamber. Silence reigned around the Assembly. Battalions of infantry occupied the area and barred the approaches, while squadrons of cuirassiers lined the palace walls. Inside, passions were running high, though no one knew quite what to expect next.

The session began at the usual hour, but the Assembly, unwilling to repeat the parliamentary comedy of the night before, had suspended its work. The members eagerly attended to reports from the streets, waited to see what would happen next, and counted the hours in feverish idleness. At a certain point a loud blare of trumpets could be heard outside. We soon learned that the cuirassiers guarding the palace had decided to amuse themselves by blowing their horns. The triumphant, joyful sound of the instruments contrasted almost painfully with the private thoughts of the members, so someone quickly issued orders to stop the unwelcome and impertinent music that had forced the deputies to confront their private forebodings.

The decision was finally made to discuss openly what everyone had been muttering about for hours. A deputy from Paris, M. Vavin, began to question the cabinet about the state of the city. At three o’clock, M. Guizot appeared at the door of the Chamber. He entered with his firmest step and haughtiest demeanor. He silently crossed the aisle and mounted the podium, practically sticking his nose up in the air lest he appear to be bowing his head. He announced straightaway that the king had called upon M. Molé to form a new government. Never have I witnessed a more theatrical announcement.

The opposition remained seated, while most of its members uttered cries of victory and satisfied vengeance. Only the leaders remained silent, privately contemplating how they would capitalize on their victory and already refraining from insulting a majority whose support they might soon need. The majority, stunned by the unexpected blow, wavered a moment, like an unsteady weight that might fall this way or that. Then its members descended tumultuously into the hemicycle. Some surrounded the ministers to ask for further information or to pay their last respects, but most delivered themselves of loud and abusive insults: “To quit the government and abandon your political allies in such circumstances is abject cowardice,” they said. Others insisted that they must march as a body to the Tuileries and force the king to reconsider his terrible decision. Such despair will not seem surprising if one recalls that most of these men felt vulnerable not only in their political positions but also in their most sensitive private interests. The government’s downfall compromised this man’s entire fortune, that man’s daughter’s dowry, and the career of yet another man’s son. It was considerations such as these that had kept nearly all of them in line. Most of them had come up in the world by indulging the government; others had thrived by doing so and were thriving still. And they hoped to continue to thrive, for the government had endured for eight years, and its supporters had become accustomed to the idea that it would endure forever. They were devoted to it in the same straightforward, unflappable way that a farmer is devoted to his field. From my bench I watched the unsteady throng of deputies. In their frightened faces I saw surprise, rage, fear, and of course greed, formerly anxious, now eager to be gratified. In my mind’s eye these legislators resembled a pack of hounds whose prey has been snatched from their half-filled mouths.

To tell the truth, moreover, had the opposition been put to such a test, many of its members would have come off just as badly. If many conservatives defended the government only to hold on to their salaries and positions, I have to say that many opponents struck me as attacking it only to win the same prizes. The truth—the deplorable truth—is that eagerness to hold public office and to live off tax receipts is not a malady peculiar to one party; it is a serious and permanent infirmity of the nation itself. It is the joint product of a democratically constituted civil society and an excessively centralized government. It is the hidden ill that gnawed away at all past governments and will continue to gnaw at all future ones.

In the end the tumult died down. What had happened became clearer. It all began when one battalion of the Fifth Legion prepared to launch an insurrection and several high-ranking officers of the unit appealed directly to the king.

When the king, who was slower to change his thinking and quicker to change his conduct than anyone I have ever known, learned what was going on, he immediately made up his mind and, after indulging the government for eight years, unceremoniously dismissed it in two minutes.

The Assembly quickly dispersed, each member preoccupied with the change in government and oblivious of the revolution.

I left the Chamber with M. Dufaure and immediately saw that he was not only concerned about what was happening but also in a bind, finding himself in the critical and complicated situation of a leader of the opposition about to become a minister. Having counted previously on the usefulness of his allies, he had begun to think about the difficulties their demands would soon create for him.

M. Dufaure had a mind somewhat given to secretive intrigue, which gave purchase to such thoughts, and a sort of natural simplicity mixed with honesty, which made it rather difficult for him to conceal them. He was also the most sincere and by far the worthiest of those who at that point stood a chance of becoming ministers. But he believed he was close to power and longed for it with a passion that was all the more irresistible for being repressed and covert. In his place, M. Molé would have been even more self-centered and ungrateful, but he would also have been more open and affable.

I soon left him and joined M. de Beaumont at his home, where spirits were running high. I was a long way from sharing the joyful mood, and since these were people with whom I could speak freely, I gave my reasons. “The Paris National Guard has just brought down a government. The new ministers will therefore rule at the pleasure of the Paris National Guard. You are glad that the government was brought down, but don’t you see that it is authority itself that has been overthrown?” Beaumont had little liking for such a counsel of gloom. “You always see the dark side of things,” he said. “Let us first rejoice in our victory. Later we can worry about what comes next.”

Mme de Beaumont, who was present during this conversation, seemed to share her husband’s ardor, and to me there was no more telling sign of the irresistible force of partisan thinking, because self-interest and hatred were naturally alien to the heart of that distinguished and appealing woman, one of the most truly and constantly virtuous individuals I have ever known and one who has always known better than anyone else how to make virtue touching and likeable.

I nevertheless stuck to my guns against both of them, arguing that all things considered, the incident was unfortunate, or, rather, that it was not just an incident but a major event that would soon change everything. To be sure, I was quite comfortable philosophizing this way, because I did not share the illusions of my friend Dufaure. The political machine had suffered too violent a jolt, I thought, for power to remain with middle-of-the-road parties like mine, and I anticipated that it would soon fall into the hands of people almost as hostile to us as those who had just forfeited it.

I went to dine with another friend, M. Lanjuinais, about whom I will have more to say later. There were numerous other guests, of all political stripes. A number of them rejoiced at the results of the day. Others were alarmed. All believed that the insurrection would soon come to a halt on its own only to erupt in a different form on another occasion. Reports from the city seemed to confirm this view. War cries gave way to shouts of joy. Among the guests was Portalis, who a few days later became chief prosecutor of Paris—not the son but the nephew of the chief judge of the Court of Appeals. This Portalis had neither the rare intelligence nor the exemplary morals nor the pious platitude of his uncle. His crude, violent, twisted mind was receptive to all the false ideas and extreme opinions of the day. Although he was later linked to most of the men who were dubbed instigators and leaders of the revolution of 1848, I can attest that on that night he no more anticipated that revolution than any of the rest of us. I am convinced that even at that critical moment one could have said the same of most of his friends. It is a waste of time to look for secret conspiracies that might produce an event of this kind. When a revolution is the result of popular emotion, it is generally desired but not premeditated. Those who boast of conspiring to bring it about actually just take advantage of it. Revolutions are the spontaneous result of a general malady of men’s minds brought suddenly to a crisis by a fortuitous circumstance no one foresaw. The alleged instigators and leaders of these revolutions instigate and lead nothing. Their merit is like that of an explorer who discovers a previously unknown land: they have the courage to press on when the wind is favorable.

I retired early and immediately went to bed. Although I was staying close to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I did not hear the shooting that did so much to turn the course of events, and I fell asleep without knowing I had witnessed the last day of the July Monarchy.

CHAPTER 4

[February 24.—The ministers’ plan of resistance.—The National Guard.—General Bedeau.]

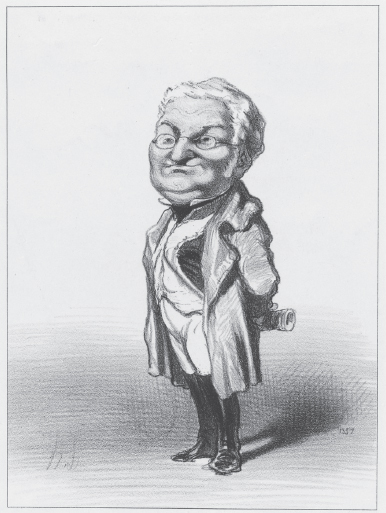

The next day, February 24, as I was leaving my bedroom, I bumped into the cook, who was just back from town. The good woman was beside herself and poured out a tearful torrent of words of which I understood nothing except that the government was massacring the poor. I immediately went downstairs and no sooner reached the street than I felt for the first time that revolution was truly in the air. The pavement was empty. No shops were open, and not a single carriage or pedestrian was in sight. The customary shouts of street vendors were absent. Neighbors gathered in small groups in front of their doors, chatting in whispers and looking anxious. Fear deformed their features—or was it anger? I met a national guardsman who was hurrying along, rifle in hand, looking tragic. I approached him but learned nothing, if not that the government was massacring the people but the National Guard would soon put things right. The refrain was always the same. This explanation of course explained nothing as far as I was concerned. I knew the vices of the July government too well not to know that cruelty was not among them. The government, in my view, was one of the most corrupting that ever existed but also one of the least bloody, and my only reason for reporting this guardsman’s remark is to show how rumors help revolutions to spread. I hastened to M. de Beaumont’s house, on an adjacent street, where I learned that the king had summoned him during the night. I received the same news at the home of M. de Rémusat, where I went next. Then I ran into M. de Corcelle, who explained to me what was happening, but his explanation was still rather mystifying, because in a city in revolution, as on a battlefield, everyone takes whatever incident he happens to see for the event of the day. From him I learned of the shooting on the boulevard des Capucines and the rapid spread of the insurrection, of which that pointless act of violence had been the cause or pretext. I learned that M. Molé had refused to take charge in such circumstances and that in the end the palace had summoned MM. Thiers, Barrot, and their friends to form a government. All of this is too well known for me to dwell on. I asked M. de Corcelle how the ministers intended to calm things down. “I gather from M. de Rémusat that the plan is to order all the troops to stand down and to inundate Paris with national guardsmen.” Those were his very words. I have often observed that in politics, having too good a memory can often be fatal.

The men who were thus charged with heading off the revolution of 1848 were precisely the same men who had made the revolution of 1830. They remembered that the army had been unable to stop them then and that the presence of the National Guard, which Charles X had so imprudently dissolved, might have caused them a good deal of trouble and foiled their plans. So they did the opposite of what the government of the elder branch of the royal line had done, yet achieved the same result. Mankind never changes, but the popular mood is in constant flux, and history never repeats itself. One era can never be directly compared with another, and an old painting forced into a new frame never looks right.

Adolphe Thiers, by Honoré Daumier, 1848

After briefly discussing the perilous state of affairs, M. de Corcelle and I went looking for M. Lanjuinais, and then the three of us went to see M. Dufaure, who was living at the time on rue Le Peletier. On the boulevard by which we traveled there, we saw a remarkable sight. The street was almost deserted, even though it was nearly nine o’clock in the morning, and not a voice could be heard, but all the little sentry boxes that line the broad avenue seemed to teeter on their bases, and from time to time one of them would topple over with a great clatter, while the huge trees that line the curb would now and then come crashing down into the street, seemingly of their own accord. These acts of destruction were the work of single individuals who toiled in silence, methodically and rapidly preparing the materials with which others would soon erect barricades. It resembled an industrial process, and for most of these men it was one; their instinct for disorder had stimulated their taste for revolution, while experience of so many previous insurrections had equipped them with a theory. I don’t think that any of the other things I would witness that day made as great an impression on me as that empty boulevard, where the worst of human passions were on display even though not a single individual was anywhere to be seen. I would rather have encountered an enraged mob, and I remember pointing out to Lanjuinais those crashing beams and falling trees and for the first time uttering the words that had long been on my lips: “Believe me, this time it’s not a riot but a revolution.”6

“Dernier conseil des ex-ministres” [last cabinet meeting of ex-ministers], by Honoré Daumier, 1848

M. Dufaure told us what concerned him about the incidents of the previous afternoon and night. M. Molé had initially called on him to help form a new government. The increasing gravity of the situation quickly persuaded both men that their moment had passed. M. Molé informed the king of this around midnight, and the king sent for M. Thiers, who was unwilling to take power without M. Barrot. Beyond that, M. Dufaure knew no more than we did.

We parted without having decided what to do next beyond turning up at the Chamber for the opening of the next session.

M. Dufaure failed to arrive, however, and I never found out exactly why. It was certainly not out of weakness, for I later saw him very calm and quite steadfast in far more dangerous situations. I think he was alarmed for his family and chose to accompany them to a safe place outside Paris. His private and public virtues, both considerable, did not march in step. The former were always in advance of the latter. As we shall see, they more than once marched together. In any case, I cannot accuse him of any great crime. Virtues of any kind are rare enough that those who have them should not be harassed about their type and relative importance.

I was with M. Dufaure just long enough for the rioters to erect numerous barricades along the route we had taken. By the time we returned, the finishing touches were being put in place. The barricades were skillfully built by a small number of people who worked quite deliberately, not as furtive criminals worried that they might be caught in the act but as careful workers intent on doing their jobs quickly and well. The public placidly looked on, neither helping nor disapproving. Nowhere did I see the seething unrest that was ubiquitous in 1830, when the entire city reminded me of a cauldron on the boil. This time the government was not toppled; it was allowed to fall.

On the boulevard we encountered a column of infantry retreating toward the Madeleine. No one spoke to the soldiers, whose withdrawal resembled a rout. The troops had broken ranks and were marching haphazardly with heads bowed and faces marked by expressions of fear mingled with shame. The minute one of them stepped out of line, he was immediately surrounded, seized, embraced, disarmed, and sent on his way. It took no longer than a blink of an eye.

On returning home I found my brother Édouard, along with his wife and children. They had been staying in the faubourg Montmartre, and shots had been fired in the vicinity of their house during the night. Frightened by the tumult, they had decided that morning to leave their home on foot and had passed through the barricades on their way to our house. My sister-in-law had, as usual, lost her composure. She already imagined her husband dead and her daughters ravished. Although my brother was as steady a man as one could imagine, he too was upset and uncertain which way to turn, driving home for me the lesson that if a courageous companion is a great help in revolutionary times, a wet hen is a cruel burden, even if she has the heart of a dove. What particularly exasperated me was the fact that my sister-in-law gave no thought at all to the country as she lamented the fate of her flesh and blood. She was a woman of demonstrative feelings rather than deep and capacious emotions. She was nevertheless a good woman and even a very witty one, but her mind was rather constricted and her heart somewhat chilled by a life of selfish piety, devoted exclusively to God, her husband, her children, and above all her health, with little interest in anyone else. One could not hope to meet a more decent woman or a worse citizen.

She embarrassed me, and I was eager to deliver myself from my embarrassment. I therefore proposed taking her to the train for Versailles, which was not far away. She was greatly afraid of remaining in Paris but also greatly afraid of leaving, and her anxiety continued to distract me while she dithered about what to do. I finally took charge of the situation and all but forced her and her family to leave for the station, where I left them and then headed back to the city.

When I reached the place du Havre, I encountered for the first time a battalion of the National Guard that had been ordered to “inundate” Paris. The guardsmen marched with a hesitant step and seemed surprised when they were surrounded by children shouting “Long live the reform!” The soldiers responded in kind, but their voices were hoarse and sounded rather forced. The battalion belonged to my district, and most of the men knew me by sight, although I knew almost none of them. They surrounded me and begged for the latest news. I told them that we had obtained everything we could possibly wish for, that the government had changed, and that reform would deal with all the alleged abuses. The only danger now was that things might veer out of control, and it was up to them to prevent this. It was clear to me that they saw things differently, however. “But sir, the government has blundered into trouble all by itself, now let it get itself out.” To which I replied: “Now look here. Can’t you see that the problem now is not the government but you? If Paris succumbs to anarchy and all of France is plunged into turmoil, do you think only the king will suffer?” But I got nowhere with them, and their only reply was the astounding sophism that since the government was at fault, it was the government that must suffer the consequences. We have no wish to get shot for the sake of those who have so badly mismanaged things. Yet the men who said this belonged to the very middle class whose every wish the government had granted for the past eighteen years. In the end, even that middle class had been swept along by the tide of public opinion and hurled against the same men who had indulged its desires so persistently as to corrupt it.

A thought that occurred to me on that occasion has often come to mind since then: in France a government is always wrong to rely for support on a single class, with its exclusive interests and selfish passions. Such a course can succeed only in nations more self-interested and less vain than ours. Here, when a government with the support of a single class becomes unpopular, the members of the class for whose benefit it has forfeited its popularity would rather denounce it along with everyone else than fight for the privileges it secured for them.

The old French aristocracy, which was more enlightened than our middle class and bound together by a much more powerful esprit de corps, demonstrated this long ago: in its final days it took pride in denouncing its own prerogatives and thundering against abuses on which it once thrived.

I therefore believe that, all things considered, the safest course for a government to take if it wishes to remain in power in France is to govern well, and above all to govern in the interest of all. Even if it takes such a course, however, there is no guarantee that it will remain in power for long.

I soon set out for the Chamber, even though it was well before the hour set for the opening of the session. I think it was around eleven o’clock. The place Louis XV7 was still empty except for several regiments of cavalry. When I saw all those troops so neatly arrayed, I thought the army had abandoned the streets only to reinforce its position around the Tuileries and the Chamber, where it would make its stand. The command staff had gathered on horseback at the base of the obelisk, led by a lieutenant general whom I recognized as Bedeau, whose unlucky star had recently brought him back from Africa only to dig the monarchy’s grave. I had spent several days with him in Constantine the year before, and this had created a somewhat intimate relationship between us, which had continued afterward. Bedeau no sooner spotted me than he jumped down from his horse, came over, and shook my hand in a way that immediately conveyed his anxiety. His conversation only reinforced this impression. This did not surprise me, because I have long noticed that the men who lose their heads most readily and prove weakest in the face of popular unrest are the men of war. Accustomed to facing organized forces and leading docile soldiers, they are easily disconcerted by the tumultuous cries of a disorderly multitude of harmless, unarmed citizens and by the hesitancy and in some cases indiscipline of their own soldiers. There can be no doubt that Bedeau was troubled, and everyone knows what came of the agitation: how the Chamber was invaded by a handful of men within a pistol’s shot of the squadrons supposed to be guarding it, after which the end of the monarchy was proclaimed and a provisional government elected. The role Bedeau played on that fatal day was, unfortunately for him, so considerable that I want to pause for a moment to consider the man and the reasons why he behaved as he did. We were close enough both before and after these events that I can speak of him here with confidence that I speak with authority. He was ordered not to fight—of that there can be no doubt. But why did he obey such an extraordinary order, which circumstances made so impossible to carry out?

Bedeau was certainly not timid or even, strictly speaking, indecisive. Once he made up his mind, he would march steadfastly, calmly, and boldly toward his objective. But he had the most methodical and self-doubting mind, the least adventurous and least prepared for surprises, one could possibly imagine. He was accustomed to considering every undertaking from every possible angle before setting to work. And he always began his review by considering the worst possible outcomes and wasted precious time diluting his thoughts in a torrent of verbiage. He was also a just, moderate, liberal, humane man, as if he had not made war in Africa for eighteen years, besides which he was modest, moral, honest, and even sensitive and religious. He was the kind of man one rarely finds in the military, or, for that matter, anywhere else. To be sure, it was not for want of heart that he did things that might suggest such a weakness, for he was a man whose courage was equal to any test. Treason was even less his motive: although he was not devoted to the Orléans, he was as incapable of betraying them as their staunchest allies and far more loyal than their toadies. His sole misfortune was to be mixed up in events greater than he was; it was to be possessed of merit when genius was required, above all that genius peculiar to revolutionary situations, which consists primarily in basing one’s actions on facts alone and knowing when to disobey. Memories of February poisoned General Bedeau’s life, leaving him with a cruel inward wound, the pain from which revealed itself in endless accounts and eternal explanations of the events of that time.

As he was explaining his perplexities to me and telling me that it was the duty of the opposition to descend as a body into the street to calm the people’s passions with soothing words, a crowd of people slipped through the trees on the Champs-Élysées and advanced via the broad avenue toward the place Louis XV. Bedeau noticed these people, dragged me toward them to a spot more than a hundred paces in front of his troopers, and began a harangue, a practice to which he seemed more drawn than any other man I ever knew with a saber strapped to his side.

While he was speaking, I noticed that the line of listeners was beginning to stretch out and would soon surround us. Beyond the front row of spectators, I could clearly make out others who looked more like troublemakers, and I also heard from the depths of the crowd the ominous words “That’s Bugeaud!” At that point I leaned over toward the general and whispered in his ear: “I have more experience of popular uprisings than you. Take my word for it: you’d best get back to your horse immediately. If you stay here, you’ll be killed or taken prisoner within five minutes.” Fortunately, he did as I suggested. A few minutes later, the men he had tried to win over massacred the troops at the Champs-Élysées guard post. I had some difficulty making my way through the mob myself. A small, squat man who seemed to be a factory worker of some kind asked where I was headed. To the Chamber, I answered, adding, to prove that I was a member of the opposition, “Long live the reform! You know that the Guizot government has been forced out?”

“Yes, sir, I know,” the man replied in a mocking tone, pointing toward the Tuileries. “But we want more than that.”

CHAPTER 5

[Chamber session.—Mme la duchesse d’Orléans.—Provisional government.]

I entered the Chamber. The session had not yet begun. The deputies wandered the corridors like lost souls, without news and feeding on rumors. It was not so much an assembly as a throng. The principal leaders of both parties were nowhere to be found. The former ministers had fled, and the new ones had yet to appear. Deputies shouted for the session to begin, not because they had any definite plan in mind but because they felt a vague need for action. The chairman declined; he was not in the habit of doing anything without orders, and since no one had issued any that morning, he had no idea what to do. I was asked to try to persuade him to take the chair, and I did so. Since even minor matters agitated him a good deal, one can easily imagine how calm he was on this occasion. I judged him to be an excellent man, and he was, although he often allowed himself to indulge in harmless deception, white lies, minor acts of treachery, and other venial sins of the sort that a timid heart and uncertain mind can suggest to an honest soul. I found him pacing his office alone in a state of considerable emotion. M. Sauzet had handsome if undistinguished features, the dignity of a Swiss guard, and a tall but heavy body to which were attached very short arms. When he was worried or anxious, as he almost always was, he flailed his arms in a spastic way like a man drowning. As we talked, he continued to move about in a peculiar manner, pacing, stopping, sitting down with one foot folded under his fat derrière as was customary with him in moments of agitation, standing up again only to sit back down, and never coming to a conclusion. It was a great misfortune for the house of Orléans that such a respectable fellow sat in the chair of the Chamber on such a day. An audacious scoundrel would have been a better choice.

In reply to my entreaties, M. Sauzet gave many reasons for not calling the session to order, but the one I found persuasive was not among them. Seeing that he was without direction and utterly incapable of finding one on his own, I felt that if he tried to lead the deputies, he would only leave them more confused than they were already. I therefore left him, and with the idea that it was more important to find people to defend the Chamber than to call it into session, I set out for the Ministry of the Interior in search of help.