Everything in this notebook (chapters I-II) was written in Sorrento at various dates in November and December of 1850 and January, February, and March of 1851.

CHAPTER 1

My judgment of the causes of February 24 and my thoughts as to what would emerge from it.

So the July Monarchy fell—fell without a fight, in the presence of the victors rather than under their blows; they were as astonished by their victory as the vanquished were by their defeat. Since the revolution of February I have several times heard M. Guizot and even M. Molé and M. Thiers say that surprise was the only reason for the collapse, which should be regarded as a pure accident, a mere stroke of fortune. In reply I have often been tempted to quote Alceste’s response to Oronte in Molière’s Misanthrope: “Pour en juger ainsi, vous avez vos raisons.”11 For those three men had led France under Louis-Philippe for eighteen years, and it was difficult for them to admit that the king’s bad policies had paved the way to catastrophe and toppled him from the throne.

Not having the same grounds for belief, I do not of course entirely share their view. I do not claim that accidents played no role in the February revolution, because in fact they played an important one, but they were not the whole story.

I have known literary men who have written history without taking part in government, and I have known political men whose only concern has been to shape events without a thought to describing them. I have often remarked that the former see general causes everywhere, while the latter, who daily experience myriad disconnected occurrences, readily imagine that everything can be attributed to specific incidents and that the little strings they are constantly pulling are the ones that move the world. Both are surely wrong.

I hate absolute systems that see all historical events as dependent on grand first causes linked together in ineluctable sequence, thus banishing individual human beings from the history of the human race. I find such theories narrow in their pretensions of grandeur and false beneath their air of mathematical truth. With all due respect to the writers who invent such sublime theories to feed their vanity and facilitate their work, I believe that many important historical facts can be explained only by accidental circumstances, while many others remain inexplicable, and finally, that chance—or, rather, that skein of secondary causes that we call chance because we cannot untangle them—plays a major part in everything that takes place on the world stage. But I also firmly believe that chance accomplishes nothing for which the groundwork has not been laid in advance. Prior facts, the nature of institutions, the cast of people’s minds, and the state of mores are the materials out of which chance improvises the effects we find so surprising and terrible to behold.

The February revolution, like any other great event of the kind, was born of general causes fertilized, as it were, by accidents. It would be as superficial to say that it derived inevitably from general causes as to ascribe it solely to accidental ones.

The industrial revolution, which for thirty years had made Paris the leading manufacturing city in France, enticed within its walls a vast new population of workers; with work on fortifications came another population, of local farmers now out of work; the passion for material pleasures, spurred by the government, which increasingly incited this multitude; the latest economic and political theories, which tended to accredit the idea that human misery is a consequence of laws rather than the work of Providence and that poverty can be eliminated by changing the basis of society; the contempt in which the governing class, and especially its leaders, were held, a contempt so widespread and so profound that it paralyzed the very people who had the greatest interest in maintaining the power that was being overthrown; the centralization that reduced the work of revolution to seizing control of Paris and of the ready-made machinery of government; and last but not least, the instability of everything—institutions, ideas, mores, and people—in an unstable society that had already been turned upside down by seven great revolutions and a host of minor upheavals in a period of less than sixty years—these were the general causes without which the revolution of February would have been impossible.

The principal accidents that led to the revolution include a maladroit dynastic opposition, which sought reform but paved the way for riot; the repression of that riot, at first too harsh, then abruptly abandoned; the sudden disappearance of all the old ministers, who took the levers of power with them, leaving the new ministers unable to find, let alone seize, the means to control the chaos; the errors and undisciplined thinking of the new ministers, who failed so abysmally to restore the power that they had so adroitly undermined; the hesitations of the generals and the absence of the only royal family members who enjoyed any measure of popularity or displayed the slightest ability; and above all the senile imbecility of King Louis-Philippe, a weakness that no one could have predicted and that remains almost unbelievable even today, despite having been laid bare by the event.

I have sometimes asked myself what might have provoked this extraordinary and sudden collapse of the king’s faculties. Louis-Philippe had spent his life in the midst of revolution and surely lacked neither experience nor courage nor intelligence, though on that fateful day all three certainly deserted him. The cause of his weakness, I think, was simply that he was overwhelmed by surprise. He was laid low before he understood what was happening. The February revolution was unforeseen by everyone, but by him most of all. No warning came to him from without, because for several years his mind had found refuge in the proud solitude that afflicts many princes after a long and happy reign, which causes them to mistake good fortune for genius and therefore to stop listening to anyone, because they believe they have nothing more to learn.

Furthermore, Louis-Philippe was deceived, as I said earlier his ministers were, by the misleading light that history casts on the present. One could compile a striking catalog of errors that have arisen one after another in response to other errors committed in dissimilar situations. Think of Charles I, driven to arbitrary rule and violence in England by the progress of the opposition under the benign rule of his father. Then think of Louis XVI, determined to endure everything because Charles I had perished out of unwillingness to endure anything. After which Charles X provoked a revolution because he took Louis XVI’s weakness as an example not to follow. And finally, Louis-Philippe, the most perspicacious of all, thought he could remain on the throne by perverting the law without violating it and assumed that if he remained within the limits of the Charter, so would the nation. To corrupt the people without confronting them; to deform the spirit of the constitution without changing the letter; to set the country’s vices one against another; to quietly drown revolutionary passion in love of material gratifications—these elements constituted the idea that governed his life. It soon became not just his leading idea but his only one. It enveloped him. He lived it. And when he suddenly discovered that it was wrong, he was like a man awakened in the middle of the night by an earthquake, who divines in the darkness that his house is collapsing and the ground is crumbling beneath his feet and feels lost and bewildered in the midst of unforeseen universal ruin.

Today I am free to sit back in my armchair and contemplate the causes that led to the events of February 24, but that afternoon I had other things on my mind, namely, the events themselves—not what produced them but what would follow.

It was the second revolution I had witnessed in seventeen years. Both had distressed me, but the impressions left by the second were far more bitter than those left by the first.

For Charles X I had felt a certain hereditary affection to the very end, but the king fell because he trampled on rights I held dear, and I hoped at the time that his fall would not extinguish liberty in France but rather revive it. On that day, however, liberty seemed dead. Although the royal family that fled meant nothing to me, I felt that my own cause was lost.

I had spent the best years of my youth in a society that seemed to be recovering its prosperity and grandeur as it regained its liberty. In it I had conceived the idea of a moderate, regulated liberty disciplined by faith, mores, and laws. I felt the charms of that liberty. It became my life’s passion. I felt that I could never be consoled for its loss, but now I saw that I must give it up.

I had acquired too much experience of men to be satisfied with vain words. I knew that while a great revolution can establish liberty in a country, several revolutions in succession can make any regulated liberty impossible for a very long time. Although I still had no idea what would come of this latest revolution, I was already certain that nothing that came of it would satisfy me, and I anticipated that no matter what fate was in store for our nephews, ours was now to live out what remained of our miserable lives between the alternative reactions of license and oppression.

I rehearsed in my mind the history of the past sixty years and smiled bitterly at the illusions we nursed at the end of each phase of our long revolution; at the theories that thrived on those illusions; at the learned daydreams of our historians; and at the many ingenious but erroneous systems with which we attempted to explain a present that we still perceived only dimly and to predict a future that we could not perceive at all.

The constitutional monarchy succeeded the Ancien Régime. The Republic succeeded the monarchy. The Empire succeeded the Republic. The Restoration succeeded the Empire. Then came the July Monarchy. After each of these successive transformations, people said that the French Revolution, having completed what they presumptuously called its work, was over. They said it and believed it. Alas! I had myself hoped it was true during the Restoration and again after the government of the Restoration fell. And now the French Revolution has begun anew, for it remains the same revolution as before. The farther we go, the more obscure its end becomes. Will we—as prophets as unreliable perhaps as their predecessors assure us we will—achieve a social transformation more complete and more profound than our forefathers foresaw or desired, or than we ourselves can yet conceive? Or must we end simply in intermittent anarchy, that chronic and incurable malady that old nations know so well? I cannot say and have no idea when this long journey will end. I am tired of mistaking deceptive mists for the shore and often wonder whether the terra firma for which we have so long been searching actually exists, or whether our destiny is not rather to ply the seas forever.

I spent the rest of that day [with Ampère], my colleague at the Institute12 and one of my best friends. He had come to see what had happened to me in the ruckus and to ask me to dinner. At first I tried to console myself by persuading him to share my grief, but I soon recognized that his impression was different from mine and that he saw the unfolding revolution with a different eye. Ampère was an intelligent man and, better yet, a man of generous heart, easy to get along with and dependable. He was loved for his good nature and liked for his witty, amusing conversation, which avoided nastiness and was filled with pointed remarks, [none of which aimed very high, to be sure,] but all of which were very pleasant to listen to. Unfortunately, he could not resist transporting the wit of the salon into literature and the literary spirit into politics. What I mean by literary spirit in politics is the error of valuing what is ingenious and new rather than what is true, what makes an interesting scene rather than what serves a useful purpose. It is responding to the talent and elocution of the actors rather than to the consequences of the play. And last but not least, it is to base one’s judgments on impressions rather than reasons. Needless to say, this defect is not confined to academicians. Indeed, the entire nation is rather prone to it, and the French people as a whole often judge politics as if it were literature. Ampère, who was the soul of kindness and whose membership in a coterie affected him only to the extent that it increased the warmth of his feeling for his friends, had nothing but contempt for the toppled government, whose recent actions in favor of the Swiss ultramontanes had irritated him greatly.13 His hatred for those Swiss and especially for their French friends was the only hatred I ever knew in him. Bores terrified him no end, but in the depths of his heart he detested only the devout. To be sure, the latter had offended him very cruelly and very clumsily, because he was not their natural adversary, and there is no better proof of their blind intolerance than the fact that they inspired such fierce hatred in a man as Christian as Ampère—Christian, I would say, not by faith but by intention, taste, and, I daresay, temperament. Ampère therefore easily consoled himself for the fall of a government that had served his detractors so well. Among the insurgents he had seen signs of selflessness and even generosity, as well as courage; the popular emotion had won him over.

I realized that not only did he not share my feelings but he actually took a diametrically opposed view. All the feelings of indignation, pain, and rage that had been accumulating in my heart since that morning therefore suddenly erupted against Ampère, and I addressed him in such violent terms, terms that only a friend as devoted as he could have excused, that I have since then felt rather ashamed whenever I think about it. Among other things, I recall saying: “You have no idea what is going on. You judge events as if you were a spectator in the crowd, or a poet. What you call the triumph of liberty is its ultimate defeat. I am telling you that these people, whom you so naively admire, have just proved that they are incapable and unworthy of living as free men. Show me what experience has taught them. What new virtues has it bestowed on them? What inveterate vices has it eliminated? No, I tell you, they are the same as they always were: just as impatient, thoughtless, and contemptuous of the law as ever; just as easily led astray by powerful voices and as rash in the face of danger as their forebears. They have not improved with time but have remained as frivolous in serious matters as they used to be in pointless pursuits.” After much shouting, we both agreed to let the future judge, for the future is an enlightened and upright arbiter—but, alas, it always arrives too late.

CHAPTER 2

Paris the day after February 24, and the days that followed.—Socialist character of the new revolution.

Resumed in Sorrento in October 1850

The night passed without incident, although shouts and rifle fire continued to be heard in the streets. These were the sounds of triumph, however, not of combat. At daybreak I went out to see what the city looked like and find out what had become of my two young nephews. They were being educated at the time in a seminary for children, an educational institution that hardly prepared its pupils to live in revolutionary times like ours and provided no security on a day of insurrection. The seminary was located on rue de Madame,14 behind the Luxembourg, so that I had to travel across a good swath of Paris to get there.

I found the streets quiet and even half-deserted, as one ordinarily finds them on a Sunday morning, when the rich are still asleep and the poor are taking their rest. From time to time I did encounter the previous day’s victors along the way, but most were headed home and unconcerned with passersby. In the few open shops I saw bourgeois who seemed not so much frightened as astonished, like spectators at the end of a play still trying to figure out what it had really been about. Now that the people had abandoned the streets, the most common sight was soldiers, either alone or in small groups, all unarmed and headed home. The defeat they had just suffered had left them with vivid and durable feelings of shame and anger. This would become obvious later on but for the time being was not apparent. Pleasure at regaining their freedom seemed to dominate any other feelings these young men may have had. They looked carefree and walked with a free and easy step, like schoolboys on vacation.

The younger pupils’ seminary had not been attacked or disturbed in any way. In any case, my nephews were no longer there, having been sent to their maternal grandmother’s house the previous evening. I therefore headed home by way of the rue du Bac to see whether Lamoricière, who was living there at the time, had indeed been killed the day before, as his aide-de-camp had announced after seeing him fall. Only after his servants recognized me did they admit that their master was in the house and allow me in to see him.

I found this uncommon man, about whom I will have more than one occasion to speak in what follows, stretched out on his bed and reduced to a state of immobility at odds with his nature and desires. His head was half broken open, bayonets had repeatedly pierced his arms, and his limbs were battered and paralyzed; otherwise he remained the same man as always, with his impassioned mind and indomitable heart. He recounted what had happened to him the day before and the thousand perils from which he had escaped only by miracle. I strongly advised him to remain at rest until his wounds healed, and for a considerable time thereafter, rather than risk his person and his reputation for no good reason in the chaos to come. This was no doubt good advice to give to a man so in love with action, and so used to acting, that after doing whatever is necessary and useful he is always ready to embark on harmful and dangerous adventures rather than do nothing at all, yet like most advice that runs counter to a man’s natural bent, it was also quite ineffective.

I spent all afternoon walking around Paris.

Two things struck me above all others that day: the first was that the just-completed revolution had been not just primarily but solely and exclusively a popular uprising that had bestowed all power on “the people” in the strict sense of the term, meaning the classes that work with their hands.

The second was how little hatred, or for that matter any other keen passion, the lower classes thus suddenly invested with sole mastery displayed in the first flush of victory.

Although the working classes often played the leading role in the events of the First Republic, they had never guided those events or exerted sole mastery over the state in either fact or law. The Convention contained perhaps not a single man of the people. It was full of bourgeois and men of letters. The war between the Mountain and the Gironde15 was led on both sides by members of the bourgeoisie, and at no time did the triumph of the former transfer power exclusively into the hands of the people. The revolution of July was made by the people, but the middle class, which instigated and led it, reaped the finest fruits. By contrast, the revolution of February seemed to have been made entirely outside and against the bourgeoisie.

In this great clash, the two principal parts of French society had finally separated, and the people, set apart, remained in sole possession of the government. This was unprecedented in the annals of our history. To be sure, similar revolutions had taken place in other countries at other times, for the history peculiar to any period, even today, no matter how new and unprecedented it seems to contemporaries, is in essence always a reflection of the ancient history of humankind. Florence in the late Middle Ages offered a small-scale version of what had just occurred here: the noble class was initially supplanted by the bourgeois class, which in turn was driven out of government, at which point a barefoot gonfalonier led the people in the establishment of a republic. In Florence, however, this popular revolution had specific and temporary causes, while here it was the result of long-standing causes so general that after sowing turmoil in France, there was good reason to believe that those same causes would wreak havoc in the rest of Europe as well. This time the goal was not simply the victory of a party. People sought to establish a social science, a philosophy, and I might almost say a common religion that could be taught to and understood by everyone. The old picture thus took on a truly novel aspect.

Throughout that day in Paris I did not see a single representative of the former forces of law and order, not a single soldier, gendarme, or policeman. The National Guard itself had vanished. Only the common people were armed, and they alone guarded public buildings, stood watch, issued orders, and meted out punishment. It was extraordinary and terrifying to see this immense city, so full of riches, entirely in the hands of those who owned nothing at all—or, rather, it was the entire nation that was now in their hands, for thanks to centralization, whoever rules in Paris commands France. Accordingly, the other classes were truly terrified. I do not think they experienced terror of such magnitude at any point in the Revolution, and the only terror to which it can be compared, I believe, is that which the civilized cities of the Roman world must have felt when they found themselves suddenly subject to the power of the Vandals and Goths.

Since nothing similar had ever been seen, many people expected unprecedented acts of violence. I never shared those fears, however. What I saw led me to anticipate strange disturbances and novel crises in the near future, but I never believed the rich would be pillaged.

I knew the people of Paris too well to ignore the fact that their first instincts in revolutionary times are usually generous. In the immediate aftermath of victory they like to boast of their triumph, display their authority, and play at being great men. Meanwhile, some sort of government is usually established, the police return to their posts and the judges to their benches, and when at last our great men wish to descend once more to the familiar realm of petty and wicked human passions, they are no longer free to do so and must resume living as ordinary decent citizens. Furthermore, we have spent so many years in insurrection that we have developed a kind of morality of disorder and a special code for days of insurrection. Under these exceptional laws, murder is tolerated and devastation permitted, but theft is strictly prohibited, though regardless of what anyone says, this does not prevent considerable theft from occurring on such days, for a society of rioters is no different from any other society, in which one always finds scoundrels who privately thumb their noses at the morality of the group and are contemptuous of its code of honor as long as they can get away with it. What reassured me, moreover, was the thought that the victors had been as surprised by victory as their adversaries by defeat. Their passions had not had time to become inflamed or embittered by battle. The government had fallen without being defended or defending itself. It had long been fought, or at any rate vigorously condemned, by the very people who in the depths of their hearts most regretted its downfall.

For the previous year, the dynastic opposition had lived in deceptive intimacy with the republican opposition, taking identical actions for contrary reasons. The misunderstanding that facilitated the revolution made it milder when it occurred. The monarchy disappeared, the battlefield seemed empty. The people no longer had a clear idea of what enemies remained to be pursued and defeated. The former objects of their wrath were gone. The clergy had never fully reconciled with the new dynasty and looked unmoved on its destruction. The old nobility applauded, no matter what the consequences might be. The former had suffered from the intolerant system of the bourgeoisie, the latter from its pride. Both despised or feared its government.

It was the first time in sixty years that the priests, the old aristocracy, and the people shared a common sentiment—of rancor, to be sure, and not affection. This nevertheless meant a great deal politically, since in politics friendships are almost always based on shared hatreds. Only the bourgeois were truly vanquished that day, but even they had little to fear. Their government had been exclusive rather than oppressive, corrupting but not violent, and it was more despised than hated. In any case, the middle class is never a compact subset of the nation or a distinct part of the whole. It always participates to some degree in the other classes and in some places merges with them. This lack of homogeneity and precise limits makes the government of the bourgeoisie weak and uncertain, but it also makes the bourgeoisie itself impossible to grasp and in a sense invisible to those who would attack it when it ceases to govern.

Taken together, these causes were responsible, I believe, for the popular languor, which I found as striking to behold as the people’s omnipotence. This languor was all the more evident because it contrasted so noticeably with the bombastic vigor of popular expression and the terrible memories it aroused. M. Thiers’s Histoire de la Révolution, M. de Lamartine’s Les Girondins, and other less celebrated but quite well known books and, to an even greater extent, plays had rehabilitated the Terror and in a sense made it fashionable. Thus the tepid passions of the day were made to speak with the inflamed rhetoric of 1793, and the names and deeds of illustrious criminals were constantly on the lips of people who had neither the energy nor the sincere desire to emulate them.

It was socialist theories—what I previously called the philosophy of the February revolution—that would later ignite genuine passions, embitter jealousies, and stir up class warfare. Although passions were initially less disorderly than one might have feared, in the aftermath of the revolution an extraordinary agitation and unprecedented disorder of popular thinking became apparent.

On February 25 a thousand peculiar theories poured from the minds of innovators into the minds of the crowd. Everything remained standing except the monarchy and the parliament, and it seemed that the shock of revolution had reduced society itself to dust and opened up a competition to decide what should be erected in its place. Everyone had a plan. One man published his in the newspapers, another posted his in one of the posters that soon covered countless walls, and still another windily harangued anyone who would listen. One aimed to destroy the inequality of wealth, another the inequality of education, while a third proposed to level the oldest of inequalities, that between man and woman. Specifics were proposed for the treatment of poverty and remedies for the malady of labor, which had afflicted mankind from the beginning.

These theories were highly diverse, often contradictory, and sometimes hostile to one another, but all aimed beyond government at government’s very basis in society and therefore shared the name “socialism.”

Socialism will remain the defining characteristic and most redoubtable memory of the February revolution. Seen in perspective, the republic will appear to have been a means, not an end.

It is not the intent of these Recollections to discover what gave the February revolution its socialist character. I will simply say that it should not have surprised observers as much as it did. Had they not noticed that the condition of the people had long been improving and that its importance, education, desires, and power had been increasing steadily? The common man’s comfort had also improved, but less quickly, and that improvement now stood close to the limit that can be achieved in an old society where people are many and places few. How could the poorer classes, inferior yet powerful, not think of escaping their poverty and inferiority by making use of their power? They had been trying to do so for sixty years. They had initially tried to help themselves by changing all the institutions of politics, but after each change they found that their lot either had not improved or had improved far more slowly than the eagerness of their desires could tolerate. It was inevitable that they would sooner or later discover that what kept them down was not the constitution of the government but the immutable laws that constitute society itself, and it was then only natural to wonder whether they might have the power and the right to change those laws as well, as they had changed the others. Consider in particular property, which is the bedrock of our social order: since all the privileges that once covered and concealed the privilege of property had been destroyed, while property itself remained the principal obstacle to equality and its only apparent sign, was it not inevitable that people who owned none would not necessarily abolish it but at least think about abolishing it?

This natural anxiety of the popular mind, this inevitable agitation of the people’s desires and thoughts, and these needs and instincts of the crowd in a sense constituted the canvas on which the innovators sketched a profusion of monstrous and grotesque designs. Their designs may be judged to be ludicrous, but nothing is worthier of the serious attention of philosophers and statesmen than the canvas on which they worked.

Will socialism continue to be shrouded by the contempt in which the socialists of 1848 are so rightly held? I ask the question without answering it. I have no doubt that the laws that constitute our modern society will in the long run be subject to many modifications. In essential respects they already have been. But will they ever be destroyed and replaced by others? It seems impracticable. I will say no more, because the more I study what the world used to be like, and the more I learn in detail about the world of today, when I consider the prodigious diversity one finds in it, not only in regard to laws but also in regard to the principles that underlie the laws and the different forms that the right of property has taken and continues to exhibit today, despite what people say, I am tempted to believe that what some call necessary institutions are often only the institutions to which we are accustomed, and that when it comes to the constitution of society, the realm of the possible is far wider than the people who live in any particular society imagine.

CHAPTER 3

Uncertainty of former parliamentarians concerning what attitude to take. My own reflections on what I ought to do and my resolutions.

In the days that followed February 24, I did not seek out or see the political men from whom the events of that day had separated me. I felt no need to do so, and to tell the truth, no desire. Instinctively, I recoiled from thinking about the wretched parliamentary milieu in which I had lived for ten years and watched the seeds of revolution germinate.

I also judged that at that point any sort of political conversation or combination was merely pretension. As insubstantial as the rumors that set the crowd in motion may have been, the movement had become irresistible. I sensed that we were in the midst of one of those great democratic floods that drown any individual or party that attempts to erect a dike against them, and during which for a period of time there is nothing to be done other than to study the general character of the phenomenon. I therefore spent all my time in the street with the victors, as if I worshiped at the altar of fortune. I neither paid homage to nor asked anything of the new sovereign, however. Nor did I even address it. I simply looked and listened.

After a few days, though, I resumed contact with the vanquished. I saw former deputies, former peers, men of letters, men of business and commerce, and landowners, who in the parlance of the day began to be referred to as “idle.” The revolution seemed no less extraordinary when thus viewed from on high than when seen from below. In this group I encountered a great deal of fear but as little genuine passion as I had seen elsewhere, along with a singular resignation and above all an absence of hope, indeed almost an absence of any thought, of renewed support for the government that had just fallen. Although the February revolution was the shortest and least bloody of all our revolutions, it had filled the hearts and minds of the vanquished with an impression of its omnipotence more powerful than that created by any of the others. I think this was primarily because those hearts and minds were devoid of political beliefs and passions, so that all that remained after so many miscalculations and so much useless agitation was a taste for well-being—a sentiment very tenacious and very exclusive but also very mild, which can easily accommodate to any form of government as long as it is allowed to satisfy itself.

What I perceived, then, was a universal effort to adapt to the event that fortune had improvised and win the sympathies of a new master. Big landowners were pleased to point out that they had always been enemies of the bourgeois class and always on the side of the people. Priests rediscovered the dogma of equality in the Gospels and assured us that they had never lost sight of it. The bourgeois themselves recalled with a certain pride that their fathers had been workers, and when they were unable, owing to the inevitable obscurity of the genealogies, to trace their origins back to an actual manual laborer, they tried at least to root their fortune in some rough-hewn ancestor who had raised himself by his own bootstraps. They took as much care to put this forebear in the limelight as they might have taken to hide him a short while earlier, for the vanity of man is such that it can take a variety of forms while retaining its essential nature. The coin has two sides yet remains the same coin.

Fear was at that point the only true passion left, so instead of breaking off relations with relatives who had thrown themselves into the new revolution, people sought closer relations with them. Many families turned to members they had previously regarded as black sheep. If one was fortunate enough to have a cousin or brother or son whose dissolute ways had led to ruin, one could be sure that the erstwhile wastrel now stood on the verge of success. If, moreover, he had made a name for himself by advancing some wild theory, his ambitions would know no limit. Most of the government’s commissars and sub-commissars were people of this sort. Relations who had previously gone unmentioned and whose families might in the old days have had them locked up in the Bastille or, more recently, sent off to work as public officials in Algeria suddenly became the glory and mainstay of the entire clan.

As for King Louis-Philippe, his irrelevance could not have been greater if he had been a member of the Merovingian dynasty. Nothing made a greater impression on me than the profound silence that suddenly enveloped his name. Not once did I hear it mentioned either among the people or higher up the social ladder. The former courtiers I saw did not speak of him and I believe had truly put him out of their minds. So powerfully had the revolution distracted them that this prince had vanished from their thoughts. Some will say that this is what becomes of any king who is toppled from his throne. More noteworthy, however, is the fact that even his enemies had forgotten him: they did not fear him enough to slander him, and perhaps not even enough to hate him—if not a greater misfortune then at least a rarer one.

I do not wish to recount the history of the revolution of 1848. I am simply trying to retrace my actions, my ideas, and my impressions over the course of revolutionary events. I will therefore skip over the first few weeks after February 24 and turn to the period immediately prior to the general elections.

The moment had come when people had to decide whether they wished to observe this singular revolution as private individuals or take part in events themselves. On this point I found the former party leaders divided. To judge by the incoherence of their language and the instability of their views, one might have thought they themselves were of two minds. Nearly all were politicians shaped by the discipline and constraints of constitutional liberty. In the midst of their habitual intrigues a great revolution had taken them by surprise, and they reminded me of boatmen used to navigating exclusively on inland waterways but now suddenly cast upon the open sea. In this new adventure the knowledge they had acquired from their short voyages was more troublesome than useful, and they often seemed more baffled and uncertain than their passengers.

M. Thiers on several occasions stated his opinion that there was no choice but to run for office and win, while on other occasions he said it would be best to stay out of the elections. I do not know whether the reason for his hesitation was his alarm at the dangers that might follow the election or his fear of not being elected.

Rémusat, who was always so clear about what could be done and so obscure about what should, explained the good reasons for staying home and the no less good reasons for participating. Duvergier was frantic. The revolution had destroyed the balance-of-powers system to which his mind had clung so tenaciously for so many years, and he felt as though he were suspended in midair. Meanwhile, the duc de Broglie had not peeked out from under his cloak since February 24, and it was in that posture that he awaited the end of society, which he took to be imminent. Although M. Molé was the oldest of all the former parliamentary leaders, or perhaps for that very reason, he alone remained resolute in the conviction that there was no choice but to take an active role and attempt to lead the revolution. Perhaps his longer experience had taught him that in troubled times the role of spectator is dangerous. Perhaps the prospect of once again having something to lead rejuvenated him and hid the danger of the undertaking from his eyes. Or perhaps having so often bent this way and that under so many different regimes, his resolve had been stiffened even as his thinking had become more supple and indifferent to the nature of his master. As for me, as one might imagine, I very carefully considered what course I should take.

Now I would like to consider the reasons I had at the time for making the choices I did, which I will set forth as straightforwardly as possible. But it is difficult to write accurately about oneself. Most people who write memoirs disclose their serious missteps and dubious inclinations only when they mistake the former for positive achievements and the latter for laudable instincts, as sometimes happens. For example, Cardinal de Retz, seeking to portray himself in what he takes to be the glorious role of a shrewd conspirator, confesses his plan to assassinate Richelieu and recounts his hypocritical devotions and charities lest we fail to recognize his cleverness. He speaks not because he loves truth but because his twisted mind unwittingly betrays his corrupt heart.

But even a writer who wishes to be sincere rarely succeeds in such an enterprise. The fault lies primarily with the public, which likes writers to accuse themselves but will not tolerate self-praise. Even friends will often find admirable candor in a writer who speaks ill of himself and unbearable vanity in one who recounts his good works, so that sincerity becomes a thankless task, all loss and no profit. The main difficulty, though, lies in the subject itself. The writer is too close to himself to see clearly. He easily loses himself amid the myriad views, interests, ideas, tastes, and instincts that caused him to act as he did. The tangle of narrow paths that remain obscure even to those who use them obscures the broad highways the will actually took on its way to its most important decisions.

I will nevertheless try to find my way through this labyrinth. It is only fair to take the same liberties with myself that I have already allowed myself to take with so many others.

So I will begin by saying that when I plumbed the depths of my heart in regard to the revolution, I was somewhat surprised to find a certain relief mingled with some surprise and a kind of joy mixed with all the sadness and fear the event occasioned. This terrible event pained me on behalf of my country but clearly not on my own. On the contrary, I felt I breathed more freely after the crisis than before. I had always felt constrained and oppressed in the parliamentary milieu that had just been swept away. It had left me feeling constantly disappointed both in others and in myself. To begin with my disappointment in myself, it did not take me long to discover that I did not have what it took to play the brilliant role I had dreamed of. Both my qualities and my defects stood in my way. Not virtuous enough to command respect, I was too honest to engage in the petty stratagems that quick success required. Note, moreover, that there was no cure for my honorable character, for it was so intimately connected with my temperament as well as my principles that without it I would have been nothing. Whenever I was obliged to speak on behalf of a bad cause or to pursue a wrong course, all my talents and passions deserted me, and I confess that nothing consoled me more for the lack of success that was often the reward for my honesty than the certainty that as a scoundrel I would never be anything but clumsy and mediocre. I wrongly believed that I would be as successful on the podium as I had been with my book. The writer’s skill is more of a hindrance than a help to the orator, however. Nothing resembles a good speech as little as a good chapter. I quickly realized this and recognized that I was classed among the speakers who are correct, ingenious, and sometimes profound but always cold and therefore impotent. I have never completely overcome this shortcoming. The problem is surely not that I lack passion, but on the podium my passion for speaking the truth always temporarily extinguishes all the others. I also learned in the end that I had absolutely none of the skills necessary to rally and lead large numbers of people. I have never been an agile speaker except in direct conversation and have always been inhibited and silent in crowds. The problem is not that in the right circumstances I am incapable of saying or doing things to please the crowd, but that is hardly enough. In political warfare great battles are rare. The essence of the party leader’s profession is to mingle constantly with his supporters and even his adversaries. He must be present and expansive on all occasions and must constantly raise or lower himself to match the intellectual level of his interlocutors. He must debate and argue unremittingly, repeat the same things over and over in a thousand different forms, and deal constantly with the same subjects.

Of all these things I am profoundly incapable. Discussing things that do not interest me much is awkward, and discussing those that interest me a lot is painful. For me, truth is such a rare and precious thing that once I have found it, I do not like to subject it to the vagaries of debate: I am afraid of extinguishing the light by waving the candle about. As for frequenting people, I know so few that I am incapable of doing so in a habitual and general way. Anyone who does not impress me with some rare quality of mind or feeling is in a sense invisible to me. Mediocre men, like men of quality, have noses, mouths, and eyes, but I have never been able to recall their individual features. I am always asking the names of people I see every day but forget repeatedly. Although I feel no contempt for them, I do not have much to do with them; I treat them as I treat clichés, which I respect because they rule the world, but they bore me profoundly.

What finally repelled me was the mediocrity and monotony of the parliamentary proceedings of my day, as well as the petty passions and vulgar perversity of the men who pretended to shape and guide them.

I sometimes think that although different societies have different mores, the morals of the politicians who run things are everywhere the same. What I am sure of is that in France all the party leaders I have known have struck me as more or less equally unworthy of leading, some owing to defects of character or real education and most for lack of any virtue whatsoever. Seldom did I discover in any of them the disinterested desire for the good of others that, for all my flaws and weaknesses, I see in myself. I therefore found it as difficult to join them as to stand alone, as difficult to obey as to lead, and in the end I nearly always lived in gloomy isolation, where I was seen as aloof and consequently misjudged. Imaginary qualities as well as flaws were regularly attributed to me. I was credited with a shrewdness and depth that I did not possess and therefore accused of ambitious cunning. My discontent with myself, my boredom, and my reserve were mistaken for arrogance, a defect that makes more enemies than the greatest of vices. Because I was silent, people believed me to be devious and underhanded. Some took me for an austere character, a sullen and bitter person, which I am not, for I often waver between good and evil with a spineless indulgence that comes close to weakness, and I forget insults so quickly that some might accuse me of lacking spirit for my readiness to overlook an affront rather than efface it with a manly response.

This cruel misunderstanding not only caused me pain but also diminished my abilities below their natural level. There is no one for whom approval is healthier than it is for me, and no one who needs the esteem and confidence of the public more in order to achieve the things of which he is capable. Are the extreme lack of confidence in my own strength and the need to seek proof of my own worth in the thoughts of others consequences of true modesty? I think they are rather signs of a great pride, which is as restless and anxious as the mind itself.

But what did most to sap my hopes and strength during the nine years I had spent in politics to that point was my constant uncertainty about what was most important to do each day. Even today this remains my most frightful memory of that period. My doubts stem, I think, from the nebulousness of my thoughts rather than any failure of courage. I never hesitate to take the most arduous path if I can see clearly where it leads. But in a world of petty dynastic parties that differed little as to ends and hardly at all as to means, about which they were equally mistaken, which path would lead to an honorable or even just a useful outcome? Where lay truth and where falsehood? Which were the wicked people and which the good? In those days I was never sure, and even today I cannot say with confidence. Most party men did not allow themselves to be daunted or discouraged by such doubts. Some never experienced them and still do not. Such men are often accused of acting without conviction. My experience suggests that this was far less frequent than people imagine. These men merely had a faculty that is precious and at times even necessary in politics, to create temporary convictions in accordance with their passions and interests of the moment, so that they are able to do honorably things that are not very honorable. Unfortunately, I was never able to see things in such artificial and self-interested ways, nor could I easily persuade myself that what was to my advantage was also consistent with the general good.

This parliamentary milieu, in which I had suffered all the miseries just described, had been destroyed by the revolution. It had ignored distinctions among the old parties and obliterated them all indiscriminately, deposing their leaders and destroying their traditions and discipline. What emerged was admittedly a chaotic and confused society but also a society in which shrewdness was less necessary and less prized than selflessness and courage; in which character was more important than eloquence or the ability to manipulate men and most importantly no place remained for a doubting mind: this way lay the country’s salvation, that way its ruin. There was no doubt about which path to follow. We could now advance in broad daylight, supported and encouraged by the crowd. True, the road seemed dangerous. But my mind is so constructed that it is less afraid of danger than of doubt. I felt in any case that I was still in the prime of life. I had no children and few needs, and above all I had at home the support—so rare and precious in a time of revolution—of a devoted woman whose firm and penetrating mind and innately noble soul would be equal to any situation and unperturbed by any setback.

I therefore made up my mind to plunge into the arena and to stake my fortune, tranquility, and life on defending not a particular government but the laws that constitute society itself. My first goal was to get elected, and I left immediately for my native Normandy to introduce myself to the voters.

CHAPTER 4

My candidacy in the département of La Manche.—Description of the province.—The general election.

The département of La Manche is populated almost exclusively by farmers. There are no large cities, few factories, and no places where workers congregate in large numbers except for Cherbourg. At first the revolution passed almost unnoticed. The upper classes offered no resistance, while the lower classes barely knew it was happening. Generally speaking, agricultural populations are slow to feel a change in the political winds and reluctant to renounce previous commitments. They are the last to stand and the last to sit back down.

My steward, a semi-peasant, reported what transpired in the region after February 24: “People say that if Louis-Philippe was sent packing, it was his fault and he deserved it.” For them, that was the whole moral of the play. But when they heard about the disorder that reigned in Paris, the new taxes that would be imposed, and the fears of a general war; when they saw commerce at a standstill and money seemingly disappearing underground; and above all when they learned that the principle of property was under attack, they realized that something more was at stake than the fate of Louis-Philippe.

The fear that had previously been confined to the upper echelons of society now extended down into the depths of the population, and a universal terror took hold of the country.

This was the state in which I found things when I arrived in the middle of March. I was immediately struck and pleasantly surprised by what I saw. To be sure, demagogues had stirred up the workers in the towns, but in the countryside all landowners, regardless of background, ancestry, education, or means, had banded together into what seemed to be a single class. The rancorous differences of opinion and rivalries of caste and wealth that had once divided them were no longer visible. Envy and pride no longer divided the peasant from the rich man or the noble from the bourgeois. Mutual confidence, respect, and goodwill reigned. Property had created a kind of fraternity among those who possessed it. The wealthy were the elder brothers, the less wealthy the younger, but all saw themselves as members of the same family with a common interest in defending their shared legacy. Since the French Revolution had vastly expanded ownership of the land, the family seemed to encompass the entire population. I had never seen anything like it, nor had anyone else in living memory. Experience proved that this unity was not as solid as it seemed and that the old parties and different classes had simply followed parallel paths without ever merging into one. Fear had affected them as a mechanical pressure affects solid bodies, which may stick together as long as pressure continues to be applied but fall apart as soon as it is removed.

In this initial period, moreover, I saw no sign of political opinions in the narrow sense of the term. It seemed that the republic had overnight become not simply the best form of government one could imagine for France but the only form. Dynastic hopes and regrets were consigned to oblivion so thoroughly that no one could remember they had ever existed. The Republic respected people and property and was seen as legitimate. What struck me most in the wake of all I have just described was the universal hatred and terror that Paris inspired for the first time. In France, provincials feel about Paris and the central government of which it is the seat much as the English feel about the aristocracy: at times they complain about it impatiently, and often they envy it, but at bottom they love it because they hope to bend its power to their own advantage. This time, Paris and the people who spoke in its name had so abused their power and seemed to take so little heed of the rest of the country that the idea of throwing off the yoke and at last acting and thinking for themselves occurred to many people relatively unaccustomed to such boldness. Of course these were vague and timid desires, ephemeral and clumsy passions that never inspired in me much hope or fear. These new feelings were subsequently channeled into electoral enthusiasms. People wanted to go to the polls and vote for enemies of Parisian demagogy, which they saw not as the normal exercise of a right but as the least dangerous way of confronting the master.

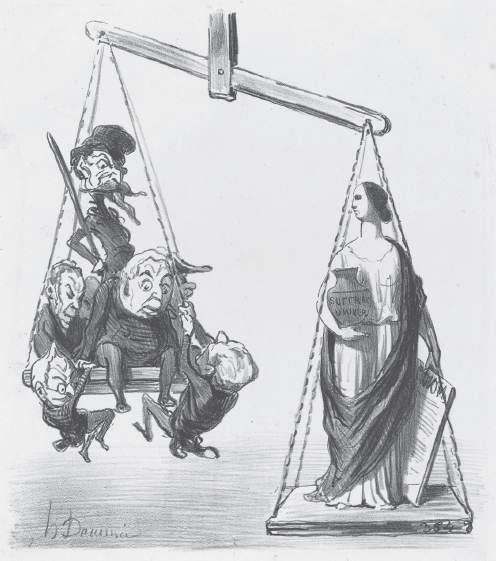

Universal suffrage, by Honoré Daumier, c. 1850

I had stopped at the small town of Valognes, which was the natural center of my influence, and as soon as I knew how things stood in the region, I set about preparing my candidacy. I quickly noticed something I have often observed in other circumstances: the surest road to success is not to want it too much. I eagerly hoped to be elected, but with the situation as difficult and critical as it was, I readily accepted that I might not be, and this calm anticipation of failure left my mind tranquil and clear and enabled me to maintain my self-respect and scorn the madness of the times as I would never have been able to do had I been consumed by the passion to succeed.

The region filled with roving candidates who hawked their republican protests on one platform after another. I refused to speak before any voters other than those who lived in the vicinity of my property.

Each small town had its club, and each club asked candidates to explain their views and actions and endorse the club’s preferred policies. I refused to respond to any of these insolent interrogations. My refusals, which might have seemed arrogant, were instead taken as signs of dignity and independence vis-à-vis the new sovereigns, and I gained more plaudits for my rebelliousness than others did for their obedience.

I accordingly limited my campaign to the publication of a circular, which I arranged to have posted throughout the département. Most of the hopefuls had revived the venerable usages of 1792. They “fraternally” addressed their fellow “citizens.” I had no desire whatsoever to cloak myself in such cast-offs of the Revolution. I opened my circular by addressing the voters as “messieurs” and concluded by proudly assuring them of my respect. “I do not come before you to solicit your votes,” I wrote. “I come only to submit myself to the orders of my country. I asked to represent you in peaceful and easy times. Honor prevents me from refusing to represent you in a time of turmoil that may become a time of danger. That is the first thing I have to say.” I added that to the end I had been faithful to the oath I had sworn to the monarchy but that the Republic, which had come into being without my cooperation, would have my energetic support. I would not merely tolerate its existence; I would actively support it. I then continued: “But what republic are we talking about? Some people think that ‘republic’ means a dictatorship in the name of liberty; that a republic should not only change political institutions but reshape society itself. Others believe that a republic should be aggressive and propagandistic. I am not that kind of republican. If you are, I will be of no use to you, because I do not share your view. But if you understand the Republic as I do, you can be sure that I will wholeheartedly dedicate myself to the triumph of a cause that is mine as well as yours.”

People who are unafraid in revolutionary times are like princes in the army: with ordinary actions they make an extraordinary impression, because they occupy a special position unlike any other and therefore enjoy great visibility. My circular met with a success that was surprising even to me. Within a few days it made me the most popular man in La Manche and focused everyone’s attention on me. My old political adversaries, the conservatives and agents of the former government who had fought me most persistently and whom the Republic had overthrown, all hastened to assure me that they were prepared not only to nominate me but to follow my advice in every respect.

Meanwhile, a preelection meeting was held of voters from the Valognes district. I appeared alongside the other candidates. The meeting took place in a building normally used as an open market. The chair sat behind a desk at one end of the structure, and a schoolteacher’s chair had been converted into a sort of podium alongside it. The chairman, a high-school science teacher in Valognes, addressed me in a loud, authoritative, but respectful tone: “Citizen de Tocqueville, I will read you the questions that have been addressed to you and that you are expected to answer.” To which I calmly replied, “Mr. Chairman, I am ready.”

A parliamentary orator whom I prefer not to name once said to me, “You see, my dear friend, there is only one way of speaking well from the podium: when you go forward to speak, you have to persuade yourself that you’re more intelligent than anyone else.” That has always seemed to me easier said than done when addressing one of our more important political bodies. In this case, however, the advice seemed to me easier to follow, and I took advantage of it. Without assuming that I was more intelligent than everyone else, I nevertheless quickly realized that I was the only one with a good knowledge of the facts at issue and a clear idea of what kind of political language people wanted to hear. It would have been difficult to be clumsier or more ignorant than my opponents proved to be. They pummeled me with questions they believed to be challenging but nevertheless left me very free, while I answered in ways that were not always very clever but invariably struck them as crushing. The principal area in which they thought they could outmaneuver me concerned the banquets. It was no secret that I had wanted nothing to do with those dangerous demonstrations. My political friends had been very critical of me for abandoning them at the time, and any number of them continued to hold my stand against me, even though the revolution showed I had been right—indeed, perhaps because it showed I had been right. “Why did you desert the opposition on the banquet issue?” they asked me. I answered forthrightly: “I could offer a pretext, but I prefer to give my real reason. I did not want the banquets because I did not want a revolution, and I venture to say that almost none of the people who attended the banquets would have done so if they had foreseen, as I did, what would follow. The only difference I see between you and me is that I knew what you were up to, but you didn’t.” Before thus professing disbelief in revolution, I had professed my faith in the Republic. The sincerity of the former profession seemed to confirm the sincerity of the latter. The audience laughed and applauded, my adversaries looked foolish, and I emerged triumphant.

In the minutes of that meeting I find the following question and answer, which I reproduce here because they reveal the preoccupations of the moment as well as my true state of mind.

Q. “If a riot were to break out around the National Assembly and people with bayonets were to burst into the Chamber, do you swear to remain at your post and if need be die there?”

A. “My presence here is my answer. After nine years of constant and futile effort to steer the recently fallen government toward a more liberal and honorable course, I would have preferred to return to private life until the storm had passed. But my honor forbade me to do so. Yes, I believe as you do that there may be perils in store for those who would seek to represent you faithfully, but along with peril there is glory, and it is because there is peril as well as glory that I am here.”16

I had won over the farmers of the département with my circular, and I won over the workers of Cherbourg with a speech.17 Two thousand of them had come together for a so-called patriotic dinner. Having received a very polite but pressing invitation to attend, I did so.

When I arrived I saw a line of marchers about to leave for the place where the banquet was to be held. At the head of the line stood my former colleague Havin, who had come from Saint-Lô expressly to preside over the event. It was our first encounter since February 24. That day I saw him offer his arm to the duchesse d’Orléans, and the following morning I learned that he had become the Republic’s commissioner in the département of La Manche. I was not surprised by this, because I knew him to be one of those restless and ambitious men who had found themselves stuck in opposition for ten years, when their intent was simply to use the opposition as a stepping-stone. How many such men had I known—men tormented by their virtue and in despair because they found themselves condemned to spend the best years of their lives criticizing the vices of others for want of an opportunity to revel in their own, circumstances having offered them no chance to abuse power other than in their imaginations! During their lengthy abstinence, most had developed such a huge appetite for places, honors, and money that it took no genius to foresee that at the first opportunity they would devour power like gluttons and show themselves to be none too choosy about the moment or the morsel. Havin was typical of these men. The provisional government had made him the partner, not to say the subordinate, of another former colleague of mine in the Chamber of Deputies, M. Vieillard, who subsequently became famous as a special friend of Prince Louis-Napoléon. Vieillard was a deserving republican, as it were, because he had been one of seven or eight republicans elected to the Chamber under the monarchy. He was also one of those republicans who had been a fixture in the salons of the empire before turning to demagogy. In literature an intolerant classicist, in religion a Voltairian, he was a rather pretentious but very kind and decent man and even something of a wit. But in politics he was extraordinarily dense. Havin used him. Whenever he wished to strike at one of his enemies or reward one of his friends, he seldom failed to employ Vieillard, who allowed himself to be used as an instrument. Havin thus hid behind Vieillard’s honesty and republicanism, which he used as a shield, much as a sapper pushes his protective apparatus in front of him when laying his mines.

Havin seemed barely to recognize me. He did not invite me to take my place in the procession. I therefore chose a modest spot among the crowd and upon arriving at the banquet hall took a seat at an obscure table. Soon the speeches began. Vieillard read from a very appropriate written text. Havin then read a second speech, which was rather well received. I was eager to speak as well but was not on the list and wasn’t sure how to insert myself into the order of the day. When one of the “orators” (for all the speakers that day thought of themselves as orators) alluded to the memory of Colonel Briqueville, I found my opening. I asked for the floor, and the audience indicated its desire to hear me. Once perched on the rostrum, or rather on the throne, which stood more than twenty feet above the audience, I felt somewhat intimidated, but I quickly recovered and delivered a rather touching address that I could not possibly reconstruct today. I know only that it was more or less appropriate to the occasion and expressed the kind of warmth that seldom fails to emerge from the disorder of an improvised address, a quality quite sufficient to ensure its success before a popular assembly—or any assembly, for that matter. For it cannot be repeated too often that speeches are made to be heard rather than read, and the only good ones are those that move their listeners.

This speech of mine met with loud cheers and total success, and I admit that it was sweet to avenge myself this way against my former colleague, who had sought to take advantage of what he took to be fortune’s favors.

If I’m not mistaken, it was between this time and the elections that I traveled to Saint-Lô as a member of the Conseil général.18 A special session of the council had been scheduled. Its composition was still as it had been under the monarchy: most of the members had bowed to the wishes of Louis-Philippe’s officials and were among those who had done most to earn that prince’s government the contempt of people in our region. The only thing I recall from that trip to Saint-Lô was the striking servility of those erstwhile conservatives. They not only did nothing to oppose Havin, upon whom they had heaped so many insults over the previous ten years, but fawned on him as assiduous courtiers. They praised him with their words, justified him with their votes, and approved his actions with gentle nods. They even spoke well of him among themselves lest some indiscretion betray their true feelings. I have seen more impressive specimens of human baseness but none more perfect. As petty as this episode was, I think it deserves to be fully aired. Subsequent events further highlighted the perfidiousness of these men: a few months later, after the shifting tides of popular opinion had brought the conservatives back to power, they immediately resumed their attacks on the same Havin with vehemence and at times extraordinary injustice. As their fear waned, their previous hatred reemerged, exacerbated by the memory of their obsequiousness.

Meanwhile, the general elections drew near, and the outlook grew gloomier with each passing day. All the news from Paris suggested that the capital was in constant danger of falling into the hands of armed socialists. There were doubts that they would allow elections to take place or refrain from forcing their will on the National Assembly. In many quarters, National Guard officers were already being forced to swear that they would attack the National Assembly if it came into conflict with the people. The provinces grew increasingly alarmed, but at the same time resolve stiffened in the face of danger.

I spent the last days before the election at my neglected, beloved estate in Tocqueville. It was my first visit since the revolution, and I knew it might be my last. Upon arriving I was overwhelmed by such intense and peculiar feelings of sadness that traces remain vividly engraved on my memory among the other vestiges of that time. No one was expecting me. The empty rooms in which I found only my old dog to welcome me, the bare windows, the jumble of dusty furniture, the cold fireplaces, the stopped clocks, the gloomy look of the place, the damp walls—all of these things presaged abandonment and ruin. I had often thought that this tiny corner of the earth, hidden among the hedges and meadows of the Norman bocage, was the most charming hermitage imaginable, but in the state of mind I was in that day it seemed to me a desolate wilderness. Yet through the desolation I glimpsed, as if from within a tomb, the sweetest, most joyful images of my past life. That man’s imagination is more colorful and vivid than reality is something I admire. I had just witnessed the fall of the monarchy and subsequently observed the most dreadful and bloody scenes. Yet none of those tragic events affected me more poignantly or profoundly than the sight of my ancestral home and the memory of the peaceful, happy days I had spent there, innocent of how precious they were. It was then and there that I tasted the true bitterness of revolution.

The local people had always been kind to me, but this time I found them affectionate as well. Never was I treated with more respect than after posters bluntly proclaiming equality appeared on every wall. We were supposed to vote as a body in the town of Saint-Pierre, one league from our village. On the morning of the election, all the voters—the entire male population above the age of twenty—assembled in front of the church. The men lined up double file in alphabetical order. I took the place that corresponded to my name, because I knew that in democratic times and countries one cannot place oneself at the head of the people but must be placed there by others. Pack horses and carts followed this long procession, bearing the crippled and sick who wished to accompany us. Only the women and children remained behind. When we reached the top of the hill that overlooks Tocqueville, we stopped for a moment. I knew that people were expecting me to speak, so I stood on a mound next to a ditch and, with everyone gathered around in a circle, said a few words inspired by the circumstances. I reminded those good people of the gravity and importance of what they were about to do. I advised them not to allow themselves to be accosted or diverted by people in town who might try to lead them astray. Instead, we should remain together as a body, each man in his place, until everyone had voted. “No one should go indoors to eat or dry off (for it was raining that day) before doing his duty.” They loudly proclaimed that they would do as I asked, and they did. Everyone voted together, and I have reason to believe that nearly all voted for the same candidate.

Immediately after voting myself, I took my leave, climbed into a carriage, and set out for Paris.

CHAPTER 5

First meeting of the Constituent Assembly.—Character of this Assembly.

I stopped at Valognes just to say good-bye to some of my friends. Several of them had tears in their eyes when we parted, for it was widely believed in the provinces that deputies would be exposed to great danger in Paris. Some of the good people I talked with told me that if the National Assembly were attacked, they would come to Paris to defend us. I regret that at the time I took these to be empty words, because those good people actually did come, along with many others, as will be seen in what follows.

It was not until I arrived in Paris that I learned I had received 110,704 of the roughly 120,000 votes cast in the election. Of the colleagues elected with me, most had been members of the dynastic opposition. Only two had professed republican opinions before the revolution: in the jargon of the day, they were what people called républicains de la veille, or “precocious republicans.”

The results were similar in most parts of France.

There have been revolutionaries more vicious than those of 1848, but none stupider. They had no idea either how to take advantage of universal suffrage or how to do without it. Had they held elections immediately after February 24, when the upper classes were still stunned and the people still more astonished than discontented, they might have obtained the Assembly their hearts desired. Had they boldly established a dictatorship, they might have clung to it for a while. But even as they submitted themselves to the judgment of the nation, they did everything they could to alienate it. They threatened the people even as they subjected themselves to the people’s judgment. They frightened citizens with the boldness of their plans and the violence of their language yet incited resistance with the indecisiveness of their actions. They behaved as though they were the people’s guardians but made themselves its dependents. Instead of opening up to new members after their victory, they jealously closed ranks and seemed to set themselves an insoluble problem, namely, how to establish majority rule against the wishes of the majority.

Following examples from the past without understanding them, they foolishly imagined that bringing the masses into politics would be enough to secure their allegiance to the cause and that to win the people’s love for the Republic it would suffice to grant rights without procuring profits.

They forgot that their predecessors had not only granted the vote to all peasants but also ended the tithe, eliminated compulsory labor service, abolished other seigneurial privileges, and divided the property of the old nobility among the former serfs, while they themselves could do nothing of the kind. By instituting universal suffrage, they thought they were summoning the people to support the revolution, whereas in fact they were arming the people to oppose it. I am nevertheless far from believing that it would have been impossible to inspire revolutionary passions, even in the countryside. In France, every farmer owns some plot of land, and most are burdened by heavy debt. Their enemy was no longer the noble but the creditor, so it was the creditor who should have been attacked. The revolutionaries should have promised to abolish debt rather than property. The demagogues of 1848 did not think of this expedient. They proved to be much less clever than their predecessors, though no more honorable, for they were as violent and unjust in their desires as the latter had been in their acts. But to commit acts of violent injustice, a government needs more than the will or even the capacity: the mores, ideas, and passions of the time must be propitious as well.

The elections therefore produced a majority opposed to the party that had made the revolution, as was only to be expected. Yet that party was surprised and pained by the results. When its candidates were rejected, it fell into depression and rage. It complained, at times mildly, at other times rudely, that the nation was ignorant, ungrateful, mad, and hostile to its own good. It reminded me of Molière’s Arnolphe saying to Agnès,

Pourquoi ne m’aimer pas, madame l’impudente?19

What was no laughing matter, however, was the state of Paris on my return, truly sinister and terrifying.

In the city I found a hundred thousand armed workers, formed into regiments, out of work, dying of hunger, but their heads filled with vain theories and chimerical hopes. I saw a society severed in two: those who owned nothing were united in common envy, those who owned something in common anxiety. Between these two broad classes no bond or sympathy remained; everywhere the idea took hold that conflict was inevitable and imminent. The bourgeois and the people (for these ancient noms de guerre had been revived) had already come to blows in Rouen and Limoges, with contrasting outcomes. In Paris, hardly a day went by without threats or damage to property owners’ income or capital. In some cases capitalists were asked to put people to work even though commerce had come to a halt, while in other cases they were asked to let their tenants pay no rent even though the landlords had nothing else to live on. When possible the owners of property gave in to these tyrannical demands but tried to profit from their weakness by publicizing it. I recall reading in one newspaper a letter to the editor that still strikes me as a model of vanity, cowardice, and stupidity artfully combined:

To the editor: I avail myself of your newspaper to inform my tenants that in the interest of putting into practice the principles of fraternity that should guide the actions of all true democrats, I shall forgive to any tenant who asks next month’s rent.

Nevertheless, a dark despair had taken hold of this oppressed and threatened bourgeoisie, and that despair slowly turned into courage. I had long despaired of a gradual and peaceful settlement of February’s revolutionary movement, believing that it would come to an abrupt end only after a great battle had been fought in Paris. I said as much in the immediate aftermath of February 24. What I saw then persuaded me that such a battle was not only inevitable but also imminent and that we should seize the first opportunity to strike.

The National Assembly finally met on May 4. Up to the last minute there were doubts that it would be able to do so. I firmly believe that the most ardent of the demagogues had been tempted on several occasions to forgo the legislature, but they did not dare. They were crushed by the weight of their own dogma of popular sovereignty.

I should have a vivid image of how that first session of the Assembly went, but my memory is somehow blurred. It is a mistake to think that only the grand and important events are engraved in our minds. It is rather the peculiar details that make certain images more memorable than others. What I remember is just that we shouted “Vive la République!” fifteen times during the session, each deputy trying to outdo the others. Similar incidents have occurred in many other legislative bodies, and it is common for one party to exaggerate its sentiments in order to embarrass its adversary, while the latter avoids the trap by feigning sentiments it does not feel. Both sides therefore felt pressure to exaggerate the truth or even deny it. I believe, however, that in this case the cries on both sides were sincere, but the thoughts behind them were different or even contradictory. Everyone at that point wanted the Republic to survive, but some sought to use it to attack their enemies, others to defend themselves. The newspapers that day spoke of enthusiasm in the Assembly and the crowd. There was a great deal of noise, to be sure, but no enthusiasm. Everyone was too preoccupied with what would come next to be distracted by any sentiment at all.