My Ministry: June 3–October 29, 1849

This section begun at Versailles on September 16, 1851, during the adjournment of the National Assembly.

Proceeding directly to this part of my recollections, I have decided to omit the period from the end of the June Days of 1848 to June 3, 1849. If I have time, I will return to this period later. It seemed more important, while my memories were still fresh, to recount the five months I spent in government.

CHAPTER 1

Return to France.—Formation of the cabinet.

While I was busy watching another act of the great European revolutionary drama unfold on the German stage, unexpected and alarming news abruptly drew my attention back to France. I learned of our army’s almost incredible defeat before the walls of Rome, of the abusive debates that ensued in the Constituent Assembly, of the agitation in the country owing to both these causes, and, finally, of the general election results, which, contrary to the expectations of both parties, brought more than 150 Montagnards into the new Assembly. Nevertheless, the demagogic wind that suddenly swept parts of France spared La Manche. Indeed, all the members of the former delegation who had split from the conservative party in the Assembly were defeated at the polls. Of the thirteen deputies in the delegation, only four survived. I garnered more votes than any of the others even though I was absent and silent and even though I had openly voted for Cavaignac the previous December. Everyone nevertheless supported me, owing not so much to my political opinions as to the great personal respect I enjoyed outside politics, no doubt an honorable position but one that would be difficult to maintain in the midst of maneuvering parties—and that would become quite precarious if the parties turned to violence and therefore became exclusive.

I left for home at once on receiving the news. In Bonn, Mme de T[ocqueville] was suddenly taken ill and had to stop. She herself urged me to leave her and continue on my way, which I did, albeit with regret, because I was leaving her alone in a country still agitated by civil war, and in any case her courage and good sense had always helped to sustain me in trying and perilous times.

I reached Paris, if I’m not mistaken, on May 25, 1849, four days before the opening of the Legislative Assembly and during the final convulsions of the Constituent.

A few weeks had sufficed to make the political scene entirely unrecognizable. It was not so much external circumstances that had changed. Rather, a prodigious change in thinking had occurred in just a few days’ time.

The party that had held power when I left the country held it still, and I felt that the outcome of the election would only strengthen its grip. That party, comprising a variety of factions that all wanted to either halt or reverse the revolution, had obtained an enormous majority in the colleges. It would make up more than two-thirds of the new Assembly. Yet I found it in the grip of a terror so profound that I can only compare it to the terror that followed the revolution of February, for in politics as in war one must never forget that the effect of an event depends not on what it is in itself but on the impression it makes.

The conservatives, who had won all the by-elections over the previous six months and who filled and dominated nearly all the local councils, had placed almost unlimited confidence in the system of universal suffrage, which they had initially greeted with boundless suspicion. In the just-completed general election, they had expected not only to win but to demolish their adversaries, and they seemed as dejected at having failed to achieve the triumph they had dreamed of as if they had actually been defeated. Meanwhile, the Montagnards, who had thought they were lost, were as intoxicated with joy and mad audacity as if the elections had assured them of a majority in the new Assembly. Why had the event deceived the hopes as well as the fears of both parties? It is difficult to say with certainty, because the great masses of men are moved by causes almost as unknown to humanity as those that govern the movements of the sea. In both cases, the causes of the phenomenon are in a sense hidden and swallowed up by its immensity.

There is nevertheless reason to believe that the failure of the conservatives was due primarily to their own errors. Their intolerance, when they were sure of winning, of those who, without sharing all their ideas, had helped them fight the Montagnards; the repressive violence ordered by M. Faucher, the new minister of the interior; and, more than anything else, the failure of the Roman expedition had turned against them a portion of the population that had been prepared to follow them, casting this group abruptly into the arms of the agitators.

As mentioned earlier, 150 Montagnards had just been elected. A good many peasants and a majority of soldiers had voted for them. These were the two sheet anchors that threatened to break in the storm. The terror was universal. It reacquainted the various monarchical parties with tolerance and modesty, virtues they had cultivated after February but completely forgotten over the previous six months. All sides recognized that for the moment there could be no question of ending the Republic and that the contest was now between moderate republicans and Montagnards.

People now accused the same ministers they had previously promoted and spurred, and loudly called for changes in the cabinet. The cabinet acknowledged its own shortcomings and called for replacements. As I was preparing to depart, the Comité de la rue de Poitiers28 had removed M. Dufaure from its lists. Now all eyes were on M. Dufaure and his friends, whom people begged in the most abject way to take power and save the country.

On the evening of my arrival, I learned that some of my friends were dining together at a small restaurant on the Champs-Élysées. I hastened there and found Dufaure, Lanjuinais, Beaumont, Corcelle, Vivien, Lamoricière, Bedeau, and one or two others whose names are less well known. They quickly filled me in on the situation. Barrot, having been invited by the president to form a new cabinet, had worn himself out in several days of vain efforts. M. Thiers, M. Molé, and their chief allies had refused to take charge of the government. They nevertheless had every intention of remaining masters of the situation, as we will see, but not of becoming ministers. The uncertain future, general instability, and difficulties and perhaps dangers of the moment kept them from moving ahead. Having been rebuffed in that quarter, Barrot had turned to us. But practical difficulties had arisen, and initially these seemed insurmountable. Barrot had already gone back several times to the natural leaders of the majority only to return to us after being rebuffed by them.

Time was running out as these futile efforts continued. The danger and difficulties were increasing as the news from Italy grew every day more alarming, and the Assembly, though dying, was in a rage and might decide at any moment to impeach the government.

I returned home, as one might imagine quite preoccupied by what I had just heard.

I was convinced that it was up to me and my friends to decide whether we would become ministers. We were obvious choices and obviously needed. I knew the leaders of the majority well enough to be sure that they would never commit themselves to take charge under a government they believed to be ephemeral; even if they had been selfless enough to do so, they lacked the courage. Their pride and their timidity sufficed to explain their abstention. Therefore, if we simply stood our ground, the government would be obliged to seek us out. But should I want to be a minister? I asked myself this quite seriously. I think I can justly say that I had not the slightest illusion concerning the real difficulties of the undertaking, and I saw the future with a clarity usually achieved only when looking at the past.

Most people expected fighting in the streets. I myself thought it was imminent. The election result had encouraged a boldness bordering on rashness in the Montagnard party, and the Rome business had given it an opportunity that I thought made street fighting inevitable. I had little fear about the outcome, however. I was convinced that although a majority of soldiers had voted for the Mountain, the army would not hesitate to confront it. The soldier who votes as an individual is not the same man as the soldier who fights with his unit. The thoughts of the one do not govern the actions of the other. The Paris garrison was very large, well led, and highly experienced in street combat, and memories of the passions and engagements of the June Days were still fresh. I was therefore certain of victory but very concerned about what would follow. The apparent end of our difficulties seemed to me only the beginning. In my judgment, those difficulties were almost insurmountable, and I think I was right.

No matter which way I turned, I saw no solid or durable base of support for our side amid the general malaise afflicting the nation. Everyone wanted to get rid of the constitution, some by way of socialism, others by monarchy.

Public opinion cried out to us, but it would have been highly imprudent to count on it. Fear drove the country toward us, but its memories, interests, instincts, and passions could hardly fail to call it back once the fear subsided. Our goal was to establish the Republic if possible, or at any rate to sustain it for a time by governing in a steady, moderate, conservative, and wholly constitutional manner, which would not sustain our popularity for very long, since everyone wanted to be done with the constitution. The Montagnard party wanted something more, while the monarchical parties wanted much less.

In the Assembly it was even worse. The vanity and self-interest of the party leaders magnified the effects of these general causes in countless new incidents. The leaders of the various parties might well allow us to take over the government, but it would have been imprudent to expect them to allow us actually to govern. Once the crisis was over, they would no doubt lay all sorts of traps for us.

As for the president, I did not yet know him, but it was clear that the only support we could count on in his councils would come from the jealousies and hatreds our common adversaries might inspire in him. His sympathies would always lie elsewhere, because our aims were not only different but inherently contrary. We wanted to breathe life into the Republic; he hoped to become its heir. We merely provided him with ministers, when what he needed was accomplices.

These difficulties, which were inherent in the situation and therefore permanent, were compounded by others that were no easier to overcome for being temporary: the revival of revolutionary agitation in parts of the country; the attitudes and habits of exclusion and violence already widespread and deeply rooted in the public administration; the Rome expedition, so ill conceived and ill led that it was now as difficult to exit as to push forward to a conclusion; and finally the legacy of errors committed by all our predecessors.

There were thus many reasons to hesitate, but inwardly I did not hesitate at all.

The idea of taking a post that frightened many others away and of rescuing society from the bad pass into which others had led it flattered both my honor and my pride. I knew that my tenure in office would be brief, but I hoped to stay long enough to do signal service for my country and enhance my own stature while doing so. That was sufficient reason to move ahead.

I immediately made three resolutions:

The first was not to refuse a ministry if a good opportunity arose.

The second was not to join the government unless my principal allies were in control of the most important ministries and in a position to maintain control of the cabinet.

My third and last resolution was to behave as minister each day as though I would be out of office the next; in other words, I resolved never to place the need to remain in office above the need to remain true to myself.

The next five or six days were entirely consumed by futile efforts to form a government. These attempts were so numerous, overlapping, and filled with minor incidents—great events one day only to be forgotten the next—that I have difficulty remembering exactly what took place, even though I myself figured centrally in some of the events. The problem was indeed quite difficult to resolve given the conditions under which we had to operate. The president sought to change the appearance of his government without sacrificing his principal allies. Although the leaders of the monarchical parties refused to take charge themselves, they did not wish to see the government placed entirely in the hands of men over whom they had no hold. If we were allowed in, it was to be in small numbers only and in lesser posts. We were seen as a necessary but disagreeable remedy to be administered only in very small doses.

The first offer was for Dufaure to join the government alone and settle for Public Works. He refused and asked for Interior and two other ministries for his friends. Interior was granted only with much difficulty, and the rest was denied. I have reason to believe that Dufaure was on the verge of accepting this offer, once again leaving me in the lurch as he had done six months earlier. Not that he was a dissembler or indifferent to what happened to his friends, but having such an important ministry almost in hand, and offered to him in a way he could honorably accept, had a strange effect on him. It did not exactly cause him to betray his friends, but it distracted him and made it easy for him to forget about us. On this occasion he stood firm, however, and since they could not have him alone, they offered to take me as well. I was the most logical choice, since the new Legislative Assembly had elected me one of its vice presidents on June 1, 1849 (by 336 votes out of 597 ballots cast). But where to put me? I considered myself qualified only to head the Ministry of Education. Unfortunately, that ministry was already in the hands of M. de Falloux, a key figure whom neither the legitimists, of whom he was one of the leaders, nor the religious party, which saw him as its protector, nor the president, whose friend he had become, wished to let go. I was offered Agriculture. I refused. In desperation, Barrot finally came in person and offered me the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I had tried hard to persuade M. de Rémusat to take that post, and what happened between us on this occasion is too typical to go unreported. I was very keen to have M. de Rémusat join us in the government. He was both a friend of M. Thiers and a man of honor—a rather rare combination. He alone could assure us, if not of that statesman’s support, then at least of his neutrality, without infecting us with the Thiers spirit. Finally, one night Rémusat succumbed to pleas from us and Barrot and agreed to join us. The next morning, however, he reneged. I knew for certain that in the meantime he had seen M. Thiers, and he himself confessed to me that M. Thiers, who at the time was openly proclaiming that we must join the government, had dissuaded him from going with us. “I realized,” he said, “that becoming your colleague will not win his cooperation but only force me to go to war with him myself before too long.” These were the kinds of men we would soon be dealing with.

I had never given a thought to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and my first reaction was to reject the offer. I felt I was unfit to take on a task for which nothing had prepared me. In my papers I find a record of my hesitation in the form of a conversation I had at dinner with some of my friends at that time.

In the end, I decided to accept Foreign Affairs on the condition that Lanjuinais also join the council.29 I had several important reasons for this request. First, I thought we needed three ministries in order to have the influence in the cabinet that we would need to succeed. Furthermore, I thought that Lanjuinais would be very useful to me in holding Dufaure to the line I wished to follow, since I did not believe I had enough influence of my own on Dufaure. Above all, I wanted at my side a friend with whom I could openly discuss anything that came up; this is an advantage at any time but particularly in a time of suspicion and volatility and a mission as risky as the one I was about to undertake.

In all these respects Lanjuinais suited me perfectly, although our natures were very different. He was as calm and tranquil as I was anxious and worried. Methodical, slow, lazy, cautious, and even meticulous, he was very reluctant to undertake anything new. Once engaged, however, he never gave ground and would persist to the end as stubbornly as a Breton peasant. When it came to expressing an opinion, he was very reserved, but when he finally did come out with it, he was very explicit, not to say blunt to the point of rudeness. In friendship one could not expect him to show any sign of enthusiasm, warmth, or passion, but by the same token there was no reason to fear faintness of heart, betrayal, or ulterior motives. In short, he was a very reliable partner and, all things considered, the most honorable man I ever encountered in public life and the least apt to allow his love of the public good to be distorted by private or self-interested considerations.

No one objected to Lanjuinais, but the problem was to find a portfolio for him. I asked for Agriculture and Commerce, which had been held since December 10 [sic] by Buffet, a friend of Falloux’s, not to say his fawning factotum on the council. Falloux refused to let his colleague go. I dug in my heels. For twenty-four hours it seemed that the new cabinet, not quite fully formed, had already dissolved. To overcome my insistence, Falloux tried a direct approach. He came to my house, where I lay ill in bed, and begged me to give up Lanjuinais and leave his friend Buffet at Agriculture. I had made up my mind and remained deaf to his entreaties. Vexed but always in control of himself, Falloux finally got up to leave. I thought all was lost, but in fact all was won. “You want him,” he said, extending his hand with that fine aristocratic grace he so deftly used to cover up even his bitterest emotions. “You want him, so I must yield. Let no one say that in such a difficult and critical moment, a consideration of a private order caused me to pass up a bargain as essential as this one. I will remain alone among you, but I hope you won’t forget that I am not only your colleague but also your prisoner.” An hour later the cabinet was formed, and Dufaure, who brought me the news, urged me to take immediate possession of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The date was June 2, 1849.

Thus came to be, after a slow and painful birth, a government that would prove to be short-lived. Throughout its lengthy gestation, the most harried man in France was surely Barrot. Sincere concern for the public good made him eager for a change of cabinet. Ambition, which was more closely and intimately intertwined with his honor than one might think, made him fervent to remain as head of the new cabinet. He therefore raced from one group to another, urging and scolding with much pathos and often much eloquence as well, addressing sometimes the leaders of the majority, sometimes us, and sometimes even the precocious republicans, whom he judged more moderate than the others—and he was prepared to take people from all camps because in politics he was as incapable of hatred as he was of friendship. Seeing him running every which way trying to put together a cabinet, I could not help thinking of a hen cackling and flapping after her brood but not terribly concerned whether it was a brood of chicks or of ducklings.

CHAPTER 2

Composition of the cabinet.—Its first actions until after the attempted insurrection of June 13.

The government was composed as follows: Barrot, minister of justice and president of the council; Passy, in charge of finance; Rulhière, war; Tracy, navy; Lacrosse, public works; Falloux, public instruction; Dufaure, interior; Lanjuinais, agriculture; and me, foreign affairs. Dufaure, Lanjuinais, and I were the only new ministers. All the others had belonged to the previous cabinet.

Passy was a man of genuine merit but not much appeal. He was rigid, clumsy, vexatious, belittling, and more ingenious than just. Yet he was more judicious when real action was needed than when talk alone would do, because, though fond of paradox in conversation, he was reluctant to act on it. I have never known a greater talker or a man who, when things went badly, was so quick to console himself with explication of the causes of the difficulty and the consequences that were bound to follow. When he had finished painting the current state of affairs in the darkest possible terms, he would smile calmly and say, “So, you see, there is virtually no hope of saving the situation, and we should expect a total disruption of society.” He was also a knowledgeable and experienced minister, in all circumstances honest and courageous and as incapable of surrender as of betrayal. His ideas, his feelings, his long-standing connection with Dufaure, and above all his inexpugnable antipathy to M. Thiers gave us confidence in him.

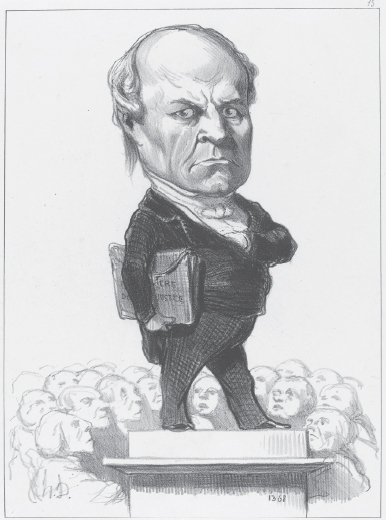

Odilon Barrot, by Honoré Daumier, 1849

Rulhière would have been an ultraconservative monarchist if he had belonged to any party at all, and especially if Changarnier had never been born. As a soldier himself, however, his only thought was to remain minister of war. As we quickly realized, he was extremely envious of Changarnier for being the army commander in Paris and keenly aware of the general’s connections with the leaders of the majority and influence on the president, so that he was forced to rely on us, and this inevitably gave us a hold over him.

Tracy was a man of weak character who initially relied on the very systematic and absolute theories he had derived from the ideological education his father had given him, which limited his thinking. Over time, however, everyday experience and the shock of revolution eroded this rigid carapace, leaving only a vacillating intelligence and a heart that, though less than stout, was always honest and benevolent.

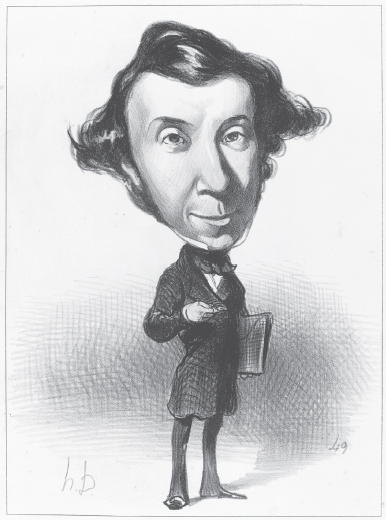

Alexis de Tocqueville, by Honoré Daumier, 1849

Lacrosse was a poor devil whose fortune was in disarray and whose mores were rather dissolute. He had been deeply involved in the old dynastic opposition, but the hazards of revolution had pushed him into the leadership, and the pleasure of occupying a ministry had not lost its luster. He was happy to rely on us, but at the same time he sought to ingratiate himself with the president of the Republic by bowing and scraping and doing various small favors. It would of course have been difficult for him to advance himself in any other way, because he was a singularly worthless individual who understood precisely nothing about anything. We were criticized for joining a government with ministers as incompetent as Tracy and Lacrosse, and our critics were right. This error was a major reason for our failure, not only because these men were poor administrators but also because their notorious inadequacy meant that their positions were in a sense always open, thus creating a sort of permanent ministerial crisis.

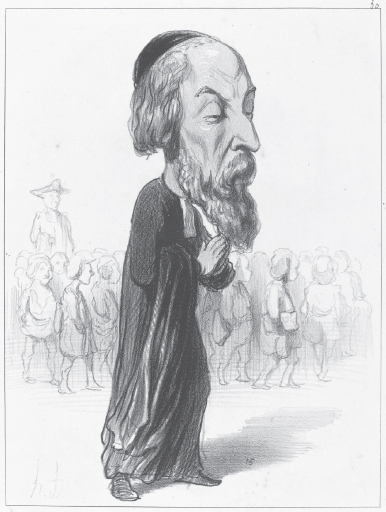

Comte de Falloux, by Honoré Daumier, 1849

Barrot’s ideas and feelings naturally inclined him to side with us. His longstanding liberal attitudes, republican tastes, and memories of his time in the parliamentary opposition made him our ally. With other associates he might have become our adversary, though not without regret, but once he joined us, we were confident of his loyalty.

Thus the only member of the government who was not familiar to us by dint of background, commitments, and inclinations was Falloux. He alone represented the leaders of the majority, or rather was thought to represent them, because in reality, as will emerge in due course, he represented only the Church—and not just in the government but elsewhere as well. His isolation, along with his unspoken policy goals, led him to seek support not from us but in the Assembly and from the president, but he did so discreetly and shrewdly, as he did everything else.

Thus constituted, the cabinet had one major weakness. It needed the support of a coalition majority to govern, but it was not itself a coalition government.

On the other hand, it derived great strength from having ministers who had similar backgrounds and identical interests and were bound together by longstanding ties of friendship, mutual confidence, and a common goal.

The reader will of course want to know what that goal was, where we were headed, and what we wanted. We live in such uncertain and upsetting times that it would be rash of me to answer for my colleagues, but I will gladly answer for myself. I did not think then, any more than I do now, that a republican government was the one best suited to France’s needs. Strictly speaking, what I mean by republican government is a government with an elected executive. In a nation whose habits, traditions, and mores have ensured that the sphere of executive power will be vast, instability of that power in troubled times will always be a cause of revolution, and in calm times a source of great malaise. I have always believed, moreover, that the republican form of government is one without checks and balances, which always promises more but delivers less freedom than a constitutional monarchy. Yet I sincerely hoped to preserve the Republic, and although there were in a sense no republicans in France, I felt that it would not be entirely impossible to do so.

I wanted to preserve the Republic because I saw nothing else at once suitable and available to replace it. A majority of the country felt deep antipathy toward the former dynasty. Fatigue with revolutions and their empty promises had quenched all political passions but one: hatred of the Ancien Régime and distrust of the old privileged classes who represented it in the eyes of the people. This feeling had survived all our revolutions undiminished and unchanged, like the water from those miraculous springs that the ancients believed could mix with seawater yet remain unadulterated and fresh. Experience with the Orléans dynasty had left little desire to return to it any time soon. It would inevitably arouse hostility in the upper classes and clergy while divorcing itself, as it had already done, from the people, thus leaving all responsibility for and profit from government to the middle classes, who had so incompetently governed the country for the past eighteen years. Nothing, in any case, indicated its imminent triumph.

Only Louis-Napoléon was prepared to take the place of the Republic, because power was already in his hands. But what could he make of his success other than a bastard monarchy, despised by the educated classes, hostile to liberty, and governed by intriguers, adventurers, and lackeys? None of these outcomes justified a new revolution.

To be sure, maintaining the Republic was a very difficult challenge because those who loved it were for the most part incapable or unworthy of leading it, while those who were in a position to establish and govern it hated it. But it would also be rather difficult to bring down. The hatred people felt toward it was an irresolute passion, as were all the passions that existed in the country at that time. In any case, people resented the republican government without loving any other. Three irreconcilable parties, more hostile to one another than to the Republic, vied for the succession. There was no majority in favor of anything.

I therefore thought that the Republic, sustained by the fact of its existence and opposed only by minorities incapable of forming a coalition, might survive thanks to the inertia of the masses, provided it was governed wisely and moderately. I therefore made up my mind to defend it and to steer clear of any attempt to bring it down. Nearly all the members of the government felt the same way. Dufaure believed more firmly than I did in the excellence of republican institutions and in their future. Barrot was less inclined than I was to respect those institutions in all situations. But at that moment we all steadfastly wished to preserve them. This common resolve was our bond and our banner.

Once the government was formed, the president of the Republic presided over a meeting of the Council of Ministers. It was the first time I had met him, having previously seen him only from a distance in the Constituent Assembly. He received us politely. It was the most we could expect, because Dufaure had vigorously opposed his candidacy and attacked him almost insultingly, while Lanjuinais and I had openly voted for his opponent.

Louis-Napoléon plays such an important role in the remainder of this story that I feel he merits a portrait of his own alongside the numerous contemporaries whom I have chosen merely to sketch. Of all his ministers, and possibly of all the men who refused to join his conspiracy against the Republic, I believe I was the one who had advanced farthest in his good graces, had studied him most closely, and was in the best position to judge him.

He was much better than one would have been warranted to believe on the basis of his previous life and insane schemes. This was my first impression on getting to know him. In this respect he disappointed his enemies and perhaps even more his friends, if one can apply that term to the politicians who backed his candidacy. Indeed, most of the latter chose him not for his worth but for his presumed mediocrity. They thought they had found an instrument they could use at will and break whenever they chose. In this they were quite mistaken.

As a private individual, Louis-Napoléon had some appealing qualities: a kindly, easy-going temperament, a humane outlook, a gentle and even rather affectionate though not at all delicate character, an excellent ability to judge people, a perfect simplicity, a certain modesty about himself mixed with immense pride in his ancestry, and a readiness to feel gratitude rather than resentment. He was capable of feeling affection and of inspiring it in those who got to know him. His conversation was sparse and sterile. He lacked the art of making others talk and establishing intimate relations with them. Although he had no facility in expressing himself, he scribbled incessantly and had something of an author’s pride. His gift for concealment—which was immense, as one would expect of a man who had spent his life in conspiracies—was powerfully assisted by the immobility of his features and the inexpressiveness of his eyes, which were dim and opaque, like the thick glass of a porthole that admits light but blocks sight. Oblivious of danger, he demonstrated admirably cool courage in moments of crisis but, as is often the case, vacillated in his designs. He changed course frequently, first advancing, then hesitating, then pulling back, to his great detriment, for the nation had chosen him to take every risk and expected audacity, not prudence. People say he had always been much given to pleasure and not very discriminating in his choices. His passion for vulgar gratifications and his taste for creature comforts only grew with the opportunities afforded by power. He squandered his energy this way daily and blunted and constricted his ambition. His mind was inconsistent and confused, filled with large but ill-assorted ideas, which he borrowed now from Napoleon, now from socialist theories, and occasionally from memories of England, where he had lived—very different and often contradictory sources. He had painstakingly collected these ideas in solitary meditation, far from contact with men and events, for he was by nature a fantastic dreamer. But when forced to exit the vast, vague world of dreams and concentrate on a specific issue, he was capable of gauging a situation accurately, at times with subtlety and breadth, but never reliably, because he was always prepared to set a bizarre idea next to a good one. It was hard to be close to him for long without discovering that his common sense was riven by a thin vein of insanity, which inevitably called to mind his youthful escapades and served to explain them.

Furthermore, he owed his success more to folly than to reason, the theater of the world being the very strange place it is: on its peculiar stage the worst plays sometimes enjoy the greatest success. Had Louis-Napoléon been a wise man or a genius, he would never have become president of the Republic.

He trusted in his own star. He firmly believed that he was an instrument of fate, the man of the hour. I am certain that he was truly convinced of his right to govern and doubt that even Charles X had greater faith in his own legitimacy. Nor was he any more capable than that monarch of explaining his faith, for although he worshiped the people in the abstract, he set little store by liberty. He hated and despised parliaments—this was the basic tenet of his political thinking. He had even less patience with constitutional monarchy than with a republican regime. Despite his limitless pride in his name, he was more than willing to bow before the nation but refused to submit to the influence of a parliament.

Like every mediocre prince, he was fond of flatterers, a taste he had had ample time to develop before coming to power thanks to twenty years of conspiring with low-life adventurers, bankrupts, crackpots, and dissipated youth—the only people who in all that time were willing to serve as his henchmen and accomplices. Despite his good manners, traces of the adventurer and gambler remained. He continued to enjoy the company of such inferiors even though he was no longer obliged to share it. I think his difficulty in expressing his thoughts other than in writing drew him to people who were long familiar with his ideas and dreams, while his inferiority in discussion made it painful for him to endure the company of intelligent men. What he desired above all was devotion to himself and his cause (as if either could inspire such devotion). Talent annoyed him if it was in any degree independent. He needed people who believed in his destiny and were willing to prostrate themselves before his future success. Hence it was impossible to get near him without passing through a group of trusted servants and friends, whom I recall General Changarnier describing to me at the time with two words: crooks and scoundrels. Nothing was worse than his familiars, unless it was his family, made up mostly of good-for-nothings and painted women.

Such was the man whom the need for a leader and the power of a memory had made the head of France, and with whom we were going to have to govern.

It would have been difficult to come to office at a more critical time. Before ending its turbulent existence, the Constituent Assembly had decided (on May 7, 1849) to order the government not to attack Rome. The first thing I learned on joining the cabinet was that an order to attack Rome had been transmitted to the army three days earlier. This flagrant disobedience of the will of a sovereign Assembly—this war launched against a nation in revolution, on account of its revolution, and despite the constitution’s insistence on respect for foreign nationalities—made the conflict we feared imminent and inevitable. How would this new confrontation end? We saw letters from prefects and police reports that alarmed us greatly. In the last days of the Cavaignac government I had seen how the self-serving flattery of subordinates could foster false hopes in the leadership. Now I saw firsthand how subordinates could contrive to instill terror in their superiors. These contrary effects stemmed from the same cause: each subordinate, judging that we were worried, sought to stand out by uncovering some new plot and providing us with some new sign of the conspiracy that threatened us. The more they believed in our success, the more willing they were to tell us of the perils we faced. Such information typically becomes rarer and less explicit as the danger increases—just when it is needed most. Subordinates who doubt that the government that bribes them is going to survive and who are already worried about what comes next will either say little or stop talking altogether. But now they were quite loquacious. Listening to them, it was impossible not to believe that we were on the brink of an abyss. I did not believe a word of what they were saying, however. I was very convinced at the time and have remained convinced ever since that official correspondence and police reports may be useful for uncovering conspiracies but give only exaggerated or incomplete and always inaccurate notions when it comes to judging or anticipating important political developments. In such matters, you have to go by the general aspect of the country and knowledge of its needs, passions, and ideas, and information of such a general character you must acquire for yourself; the best placed and most trustworthy agents can never provide it for you.

My general sense at that time was that there was no need to fear an armed revolution, but there might be fighting, and civil war is always a terrible thing to anticipate, especially when combined with fear of an epidemic. Paris was in fact ravaged by cholera at the time. Death struck people of all ranks. A substantial number of deputies of the Constituent Assembly had already succumbed, and Bugeaud, who had survived Africa, lay dying.

Had I been in the slightest doubt that a crisis was imminent, the sight of the new Assembly would have convinced me. Within the Chamber the atmosphere was already that of civil war. Speeches were brief, gestures violent, words overheated, and insults outrageous and direct. Our temporary meeting place was the old Chamber of Deputies, a room built for 460 members and scarcely able to accommodate 750. Though our flesh touched our neighbor’s, we hated each other. Despite our mutual loathing, we were crushed together; our discomfort only increased our wrath. It was like fighting a duel in a barrel. What would hold the Montagnards back? There were enough of them in the nation and the army to foster a sense of strength yet too few in parliament to give them hope of dominating or even influencing the outcome. The temptation to resort to force was therefore strong. Europe, still in turmoil, might once again be thrust into revolution by a strong blow struck in Paris. For men of such savage temperament, this was more than enough.

It was easy to see that the crisis would erupt when people learned that the order to attack Rome had been given and the attack had taken place. And this turned out to be the case.

The order remained secret, but on June 10 the first news of fighting spread.

On the eleventh, the Mountain erupted in a furious burst of rhetoric. From the podium Ledru-Rollin called for civil war on the grounds that the constitution had been violated, adding that he and his friends were prepared to defend it by all available means, including force of arms. He also called for prosecution of the president of the Republic and the previous government.

On the twelfth, the Assembly committee charged with examining the question raised the previous day rejected the call for prosecution and called on the Assembly to vote immediately on the fate of the president and the ministers. The Mountain opposed this and called for evidence to be produced. What was its goal in delaying debate? It is difficult to say. Did it hope to arouse anger on the question, or did it secretly hope to calm things down over time? There is no doubt that despite the intemperance of their language, the party’s principal leaders, who were more accustomed to talking than to fighting and more impassioned than resolute, demonstrated a hesitancy in their approach that day that had not been evident the day before. Having partially drawn their sword, they seemed ready to sheathe it again, but it was too late: their friends outside the Chamber had seen the signal, and from that point on they ceased to lead and became followers instead.

During those two days I found myself in a very cruel situation. As noted, I entirely disapproved of the way the Rome expedition had been decided and conducted. Before joining the government, I solemnly told Barrot that I intended to take responsibility for the future only and that it would be up to him to defend what had been done in Italy previously. Only on that condition did I accept the ministry. I therefore said nothing during the debate on the eleventh and left it to Barrot to defend the war effort by himself. But on the twelfth, when I saw my colleagues threatened with prosecution, I could abstain no longer. The demand for fresh evidence gave me an opportunity to intervene without having to express my opinion about the substance of the matter. My speech was brief but vigorous.

When I read what I said in the Moniteur, I find my words rather insignificant and quite badly chosen. I was nevertheless much applauded by the majority, because in a moment of crisis, with civil war at hand, what counts is robustness of expression and tone of voice rather than choice of words. I went straight after Ledru-Rollin, whom I angrily accused of asking for trouble and spreading lies to create it. Strong emotion had driven me to speak, and my tone was determined and aggressive, so even though I spoke very badly, because I was still uncomfortable with my new role, my words were greatly appreciated.

Ledru responded by saying that the majority was supporting the Cossacks. In reply he was told that he belonged to the party of looters and arsonists. Thiers was inspired to say that there was an intimate tie between the man who had just spoken and the insurgents of June. By a large majority the Assembly rejected the demand for prosecution and adjourned.

Although the Montagnard leadership continued to insult us, they did not seem very determined, so we were able to persuade ourselves that the decisive moment of the struggle had not yet arrived. We were wrong. According to reports we received that night, preparations for armed combat were under way.

Indeed, the next day, the language of the demagogic newspapers revealed that their editors were counting on revolution, rather than the courts, to absolve them. All called either directly or indirectly for civil war. The National Guard, students, the people—all were urged to gather without arms in certain designated places in preparation for a mass march on the National Assembly. The idea was to begin with a May 15 and end with a June 23.30 Seven thousand to eight thousand people assembled at the Château-d’Eau at around 11 o’clock. On our side, the cabinet met with the president of the Republic, who was already in uniform and prepared to mount his horse the moment he heard the battle had begun. Nothing had changed but his dress. In other respects he was the same man as the day before, with the same somewhat gloomy aspect, the same slow and embarrassed speech, and the same dullness in his eyes. There was no sign of the nervousness or giddiness that sometimes signals the approach of danger, but such signs may of course be no more than indications of an agitated mind.

We summoned Changarnier, who explained how he had deployed his troops and assured us that victory was at hand. Dufaure recounted the reports he had received, all of which warned of a significant uprising. He then returned to his headquarters at the Ministry of the Interior. At around noon I went to the Assembly.

The adjournment had proved to be quite lengthy, because the president, in setting the agenda the day before, had declared that there would be no meeting the following day. This was a strange oversight, which in anyone else might have been taken as a sign of treason. Messengers were sent to summon the deputies from their homes, while I joined the president of the Assembly in his office, where most of the leaders of the majority were already gathered. Their faces reflected considerable agitation and anxiety. They simultaneously feared and longed for battle, and some began to criticize the government for wavering in its resolve. Thiers, reclining in one armchair with his legs supported by another, rubbed his stomach (having experienced some symptoms of the prevailing malady) while loudly and irritably proclaiming in his shrillest falsetto that it was very odd indeed that no one had thought of declaring Paris to be in a state of siege. I calmly replied that we had thought of it but that because the Assembly was not yet in session, the moment had not yet arrived.

Deputies streamed in from every direction, drawn less by the message we had sent, which most had not received, than by rumors circulating throughout the city. At two o’clock the session began. The majority benches were full, while those of the Mountain were empty. The gloomy silence that enveloped the upper benches was more frightening than the usual catcalls from that quarter of the Chamber. It meant that the debate was over and the civil war had begun.

At three o’clock Dufaure asked that Paris be declared in a state of siege. Cavaignac backed him up with one of the short speeches he made from time to time, in which his normally mediocre and obscure intelligence rose to the height of his soul and approached the sublime. In such circumstances he briefly became the most truly eloquent speaker I have ever heard. He left all the mere speechifiers in the dust.

Addressing the Montagnard who was on his way down from the podium,31 he said:

You say that I fell from power. I did step down. The national will does not overthrow. It orders, and we obey. I will add this, that I hope the republican party will always be able to say with justice, “I stepped down, honoring my republican convictions by my conduct.” You said that we lived in terror: history was there; it will speak. But what I say is that you never inspired terror in me. You inspired deep pain. Do you want my final word? You were precocious republicans, while I did not seek a republic before it existed. To my regret, I did not suffer for it. But I have served it devotedly, and what is more, I have governed it. I will not serve anything else. Hear me well! Write what I say, stenographer! Write it! May it remain engraved in the record of our deliberations: I will not serve anything else. Between you and us, the question is, who will serve the Republic best?

Hear me! What pains me is that you have served it so badly. For my country’s sake, I hope that the Republic is not destined to perish, but if we are condemned to such a painful fate, remember this well: we will blame its failure on your exaggerations and your frenzy.

Shortly after the state of siege was proclaimed, we learned that the insurrection had been put down. Changarnier and the president, leading the cavalry, had cut off and dispersed the column headed toward the Assembly. A few barricades, just barely constructed, had been destroyed, almost without a shot being fired. The Montagnards, surrounded in the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, where they had made their headquarters, had either been arrested or fled. We were in control of Paris.

Similar movements had occurred in several other large cities, and although the fighting was more intense, the insurgents were no more successful than in Paris. In Lyon the battle raged for five hours, and for a while the outcome was in doubt. In any case, having triumphed in Paris, we did not worry much about the provinces, because we knew that in France, Paris makes the law, whether for order or against it.

Thus ended the second June insurrection, very different from the first in terms of violence and duration but similar in the reasons for its failure. In the first, the people, impelled not so much by opinion as by appetite, had fought alone, unable to find deputies to lead them. This time, the deputies had been unable to persuade the people to fight alongside them. In June 1848 the army lacked generals; in June 1849 the generals lacked an army.

The Montagnards were a strange lot. Their quarrelsome nature and pride emerged most clearly where these traits were least appropriate. Among those who, personally and through their newspapers, had most vehemently insulted us and called for civil war was Considerant, Fourier’s disciple and successor and the author of so many socialist fantasies, which would have been merely ridiculous in another time but were dangerous in ours. Along with Ledru-Rollin, Considerant managed to escape from the Conservatoire and make his way to Belgium. I had previously had social relations with him, and he wrote me from Belgium:

My dear Tocqueville,

[Here he asked a favor of me, to which he added:]

Count on me if you should need any personal favor in the future. You may survive for another two or three months, and the pure Whites who come after you may hold out for another six months at most. Sooner or later, you will of course get what you have coming to you, and you will fully deserve it. But let us say no more about politics and respect the very legal, very fair, and very Odilon Barrotesque state of siege.

To which I answered:

My dear Considerant,

What you ask is done. I do not wish to boast of such a small service, but I am very pleased to note that those odious oppressors of liberty called ministers inspire such confidence in their adversaries that the latter, having declared us outlaws, do not hesitate to turn to us in full confidence of receiving fair treatment. This proves that there is still some good in us, no matter what people say. Are you quite sure that if our roles were reversed, I would be able to do the same and ask a favor, not of you, but of one or another of your political allies, whom I might name? I think not, and I solemnly declare that if ever they are in charge and leave me with my head, I will consider myself satisfied and ready to declare that their virtue has exceeded my hopes.

CHAPTER 3

Domestic government.—Intestine quarrels in the cabinet.—Its difficulties with the majority and the president.

We were victorious, but as I expected, our real difficulties were about to begin. My maxim has always been that the danger of disaster is usually greatest after a major success: as long as there is peril ahead, there are only adversaries to face, and they can be defeated, but once victory is in hand, you have to deal with your own side—with its weakness and pride and the incautious sense of security that victory brings—and this brings you down.

I was exempt from the last of these dangers because I was under no illusion that we had overcome the main obstacles we faced, which I knew were in the very men with whom we were going to have to govern. Far from protecting us from the ill will of our partners, the rapid and total defeat of the Mountain instantly made us vulnerable. We would have been far stronger had we been less successful.

At that point the majority was made up primarily of three parties (the president’s party was still too small and too little respected to carry much weight in parliament). At most, sixty to eighty deputies sincerely cooperated in our efforts to establish a moderate republic. This group constituted our only solid support in the entire Assembly. The rest of the majority included around 160 legitimists, together with former allies or supporters of the July Monarchy, mostly representatives of the middle classes, which had governed, not to say exploited, France for the past eighteen years. Of those two groups, I immediately felt that it would be easier for us to enlist the support of the legitimists, who had been excluded from power under the previous government and therefore had no lost posts or salaries to complain about. Mostly major landowners, they did not need public offices in the way the bourgeois did, or at any rate they had not become so accustomed to the emoluments of public service. Though less inclined on principle to accept the Republic, they were more willing than some to tolerate its survival because it had destroyed their enemy and given them access to power. It had served both their ambition and their revenge. Their opposition stemmed solely from fear, which, truth be told, was quite substantial. The former conservatives who made up the bulk of the majority were keener to be done with the Republic, but because their virulent hatred was kept in check by their fear of the dangers to which they would be exposed if it were abolished prematurely, and because they had long been in the habit of following wherever power led, it would be easy for us to control them if we could obtain the support or even the neutrality of their leaders, M. Thiers and M. Molé of course chief among them.

Having clearly grasped the situation, I understood that all our secondary goals would have to be subordinated to the primary one, which was to prevent the overthrow of the Republic and above all to stop Louis-Napoléon from establishing a bastard monarchy—for the time being, this was the most immediate danger.

My first thought was to protect myself from our friends’ mistakes, for I have always found a great deal of sense in the old Norman proverb “God preserve me from my friends, and I will take care of my enemies myself.”

The leader of our supporters in the National Assembly was General Lamoricière, whose idleness I dreaded even more than his petulance and his habit of speaking rashly. I knew him to be a man who would rather do good than ill but rather ill than nothing at all. I thought of offering him an important embassy in a distant land. Russia had spontaneously recognized the Republic. It was therefore appropriate to resume diplomatic relations between our two countries, relations that had been all but broken off under the previous government. For this extraordinary but remote mission I thought of Lamoricière. He was the ideal person for the post, in which it was scarcely possible for anyone but a general, indeed a celebrated general, to succeed. I had some difficulty persuading him to accept, but my greatest challenge was to persuade the president of the Republic, who at first resisted, to take him. With a sort of naiveté that revealed not so much his frankness as his difficulty in expressing himself (for his words seldom revealed his thinking but sometimes allowed one to guess at it), he told me that for the major capitals he wanted ambassadors of his own. That was not what I wanted, because it was my job to instruct those ambassadors, so I wanted them to serve France, not the president. I therefore insisted but despite my insistence would have failed had it not been for Falloux’s assistance, Falloux being the only minister the president trusted. Falloux persuaded him, I know not how, and Lamoricière set off for Russia. I will recount later what he did there.

His departure reassured me that we could count on our friends, so I turned next to retaining or winning over the allies we needed. The first order of business was to secure the allegiance of the other ministers, which was not easy, because the cabinet included some of the most honest men you can imagine but men so rigid and limited in their political vision that I sometimes regretted that I was not dealing instead with intelligent scoundrels.

As for the legitimists, my view was that our best course was to grant them considerable influence over the Ministry of Public Instruction. This was a major sacrifice, I admit, but it was the only thing that could satisfy them and win their support in restraining the president and preventing him from overturning the constitution. This plan was followed. Falloux was granted a free hand in running his department, and the cabinet allowed him to present to the Assembly his education bill, which became law on March 15, 1850. I also used all my influence to urge my colleagues to cultivate good relations with the leading legitimists. What is more, I followed my own advice and was soon on better terms with them than any other member of the cabinet. Ultimately I became the sole intermediary between them and us.

To be sure, my background and the society in which I was raised gave me considerable advantages in this regard, which the others did not possess. Although the French nobility has ceased to be a class, it has remained a sort of freemasonry whose members continue to recognize one another by who knows what invisible signs even when their individual views make them strangers or adversaries.

So, having clashed with Falloux more than anyone else before joining the government, I readily befriended him afterwards. What is more, he was a man worth cultivating. I am not sure I ever encountered a rarer specimen in my entire political career. He had the two qualities any party leader needs: ardent conviction, which made him steadfast in pursuit of his goals, undeterred by disappointment or danger, and a rather unscrupulous intelligence, at once subtle and unyielding, which employed a prodigious variety of means in furtherance of a single unwavering plan. He was honest in that, as he put it, he acted solely for the sake of his cause and never in his own personal interest, yet he was also uncommonly and effectively crafty, capable of thoroughly mixing up the true and the false in his own mind before serving the mixture up to others. This is the one secret a man needs to know if he wishes to lie without forfeiting the benefits of sincerity or to induce his associates and followers to err in a way he deems beneficial to the cause.

No matter how hard I tried, I was never able to establish tolerably decent, let alone warm, relations between Falloux and Dufaure. To be sure, their qualities and defects were precisely opposite. Dufaure, who in his heart remained a true bourgeois of western France, an enemy of nobles and priests, could never get used to Falloux’s principles or even his refined good manners, which of course delighted me. With great effort I did manage to persuade him that Falloux should be left to run his own department as he saw fit, but Dufaure absolutely refused to allow Falloux the slightest influence over the Ministry of the Interior even when such influence was legitimate and necessary. In his native Anjou, Falloux had to contend with a prefect about whom he believed he had grounds for complaint. He did not ask to have the man dismissed from his post or even denied promotion but merely wanted him moved to another place. He felt that his own position was compromised until this change was made, and what is more, a majority of the Maine-et-Loire delegation supported his request. Unfortunately, the prefect was an outspoken republican. That was enough to arouse Dufaure’s suspicions and persuade him that Falloux’s only purpose was to get him in trouble by using him to punish republicans no one had previously dared touch. So he refused. Falloux insisted. Dufaure dug in his heels. It was rather amusing to watch Falloux prance around Dufaure and deploy all his grace and skill without ever managing to change his mind.

Dufaure would let Falloux carry on, offering only a laconic reply, either avoiding the other man’s gaze or at most darting a veiled sideways glance in his direction: “I’d like to know why you didn’t take advantage of your friend Faucher’s term as minister of the interior to get rid of your prefect.” Falloux would restrain himself, although I believe Dufaure made him very angry. He would come to me with his complaints, and beneath his honeyed words I could detect the bitter taste of bile. So I intervened: I tried to make Dufaure see that this was the sort of request one could not refuse to a colleague without straining relations to the breaking point. I spent a month shuttling back and forth between the two men, expending more effort and diplomacy on this matter than on important European affairs during that entire time. The government was on the brink of collapse at several points in this wretched affair. Dufaure finally gave in, but with so little grace that no one felt grateful toward him. In the end, he sacrificed his prefect without winning over Falloux.

But the most difficult part of our role was to know how to behave toward the old conservatives, who, as mentioned earlier, made up the bulk of the majority.

The conservatives sought both to promote their general views and to satisfy any number of private passions. They favored a vigorous restoration of order. On this point we were with them: we too wanted to restore order and did so as vigorously as they could have wished and more effectively than they could have done themselves. We had placed Lyon and a number of adjacent départements in a state of siege, and we suspended publication of six revolutionary newspapers in Paris. We also disbanded three legions of the Paris National Guard that had failed to act decisively on June 13, and we arrested seven deputies for overt resistance and called for the impeachment of thirty others. Similar measures were taken throughout France. Circulars addressed to all officials made it clear that they were dealing with a government that would demand obedience and insist that everyone follow the law.

Whenever any of the Montagnards still in the Assembly attacked Dufaure for these measures, he would answer with the sharp, muscular, virile eloquence for which he was noted, speaking in the tone of a man who has burned all his vessels before going into battle.

The conservatives wanted us not just to govern vigorously but to take the opportunity afforded by our victory to impose repressive and preventive laws. We ourselves felt the need to take steps of this sort, but we did not want to go as far as they wanted us to. I, for one, felt that it was wise and necessary to make major concessions to the nation’s legitimate terror and resentment and that the only way to preserve liberty after such a violent revolution was to restrict it. My colleagues agreed. We therefore proposed a law to suspend clubs; a second law to punish press violations even more aggressively than under the monarchy; and a third to regularize the state of siege.

Voices of protest were raised: “You are instituting a military dictatorship!” To which Dufaure replied:

Yes, it is a dictatorship, but a parliamentary dictatorship. No individual right can take precedence over society’s imprescriptible right of self-preservation. Any government, whether monarchical or republican, faces certain imperious necessities. Where do those necessities come from? To whom do we owe the cruel experience of the past eighteen months of violent agitation, endless conspiracy, and armed insurrection? Yes, you are surely right to say that after so many revolutions in the name of liberty, it is deplorable that we must once again veil her statue and place terrible weapons in the hands of the authorities! But whose fault is that, if not yours? And who serves republican government best: those who foster insurrection or those who, like us, try to stamp it out?

These measures, these laws, and this language pleased the conservatives but did not satisfy them. In truth, nothing short of destruction of the Republic would have satisfied them. That was where their instincts incessantly drove them, although prudence and reason held them back.

But what they required above all was to oust their enemies from office and replace them as quickly as possible with their own supporters and friends. We thus had to contend with all the same passions that had brought down the July Monarchy, passions the revolution had not destroyed but merely starved. This was our great and permanent stumbling block. Once again I felt that there were concessions to be made. The vagaries of revolution had brought countless incapable and unsound republicans into office. My view was that we would do best to get rid of them at once, without waiting to be asked, so as to bolster confidence in our intentions and acquire the right to defend the honest and capable republicans who remained. On this point, however, I was never able to bring Dufaure around. “What did we undertake to do?” I often asked him.

Did we set out to save both the Republic and the republicans? No, because most of the people who call themselves republicans would certainly kill us along with it, and in the Assembly there are not a hundred deputies worthy of the name. We undertook to save the Republic in conjunction with parties that do not love it. Therefore, we cannot govern without concessions, although we must be careful not to concede any point of substance. In this area our actions must above all be measured. At this point the Republic’s best and perhaps only hope of survival depends on our remaining in power. We must therefore take every honorable step to ensure that we do.

To which he would respond that when one devoted all one’s energy, as he did, to fighting socialism and anarchy day in and day out, one was bound to satisfy the majority—as if people are ever satisfied when one attends to their opinions without taking their vanity and private interests into account. If only he had known how to refuse gracefully. But he did not: the way he refused was even more irritating than the fact of his refusal. I have never been able to understand how a man so fully in command of his rhetoric at the podium, so skilled at choosing the arguments and words most apt to please, and so clever at shading his meaning in such a way as to make it most acceptable to his audience could be so ill at ease, depressing, and clumsy in conversation. It was a product, I think, of his early upbringing.

He was a man of great intelligence—or rather talent, for he had little intelligence in the strict sense of the word—but no knowledge of the world. As a young man he had been hardworking and focused, almost antisocial. At forty he married and withdrew into family life, where he no longer lived in solitude but remained in retreat. In truth, not even politics drew him out. He remained aloof not only from intrigue but from all contact with the parties, hating the business of parliament, fearing the podium, though it was his only strength, yet ambitious in his own fashion; his was a measured and rather subaltern ambition that sought only to manage rather than to rule. As a minister, he sometimes treated people in very strange ways. One day General Castellane (a sad fool, to be sure, but one who enjoyed a good reputation) asked to see him. He was received and explained at some length what he wanted and what he thought he was due. Dufaure listened patiently and attentively, then got up, accompanied the general to the door with much bowing and scraping, and then left him standing there openmouthed without Dufaure’s having spoken a single word. When I reproached Dufaure for this behavior, he said, “I would have had to say unpleasant things to him. Wasn’t it kinder to say nothing at all?” Naturally one was unlikely to leave a meeting with such a man in anything but very bad humor.

Unfortunately, he was assisted by a chief of staff as uncouth as he was and very stupid to boot, so that when petitioners went from the minister’s office to his secretary’s seeking a little consolation, they encountered the same gruffness without the intelligence. It was like struggling through a dense hedgerow only to fall into a thicket of brambles. Despite these shortcomings, the conservatives tolerated Dufaure because he avenged them so well from the podium for the insults hurled by the Montagnards, but he never won over their leaders.

As I had anticipated, the conservative leadership did not want either to take charge of the government or to allow anyone else to govern independently. From June 13 until the final discussions about Rome—in other words, for nearly the entire duration of the government—I do not think a day went by when they did not lay some ambush for us. True, they never fought us openly, but they constantly and secretly aroused the majority against us, attacked our decisions, criticized our measures, interpreted our statements in an unfavorable light, and without seeking directly to overthrow us contrived to undermine our support so that they could bring us down easily when the opportunity arose. In the end, Dufaure’s suspicions were not totally unfounded. The leaders of the majority sought to use us to implement harsh measures and repressive laws that would facilitate the task of succeeding governments. Our republican views made us a more suitable instrument for taking such steps at that juncture; later they intended to get rid of us and put their own pawns in our place. They not only sought to prevent us from consolidating our support in the Assembly but also worked tirelessly to prevent us from gaining influence over the president. They were still operating under the illusion that Louis-Napoléon would gladly submit to their control. They therefore besieged him. From our agents we learned that most of them, but especially M. Thiers and M. Molé, saw him constantly in private and did everything in their power to persuade him to overthrow the Republic in concert with them, promising to share both the costs and the benefits. After June 13 I lived in a constant state of alarm, afraid that they would take advantage of our victory to push Louis-Napoléon into usurping power by force: one fine morning, as I said to Barrot, we would wake up to find him astride the empire. I later learned that my fears had been well founded, even more so than I believed at the time. After leaving the ministry, I heard from a trustworthy source that in July 1849 there had been a plot to change the constitution by force through the combined efforts of the president and the Assembly. The leaders of the majority and Louis-Napoléon had agreed to this plan, and the coup failed only because Berryer refused to commit himself or his party, because he either feared a double cross or, when the time came to act, was seized by panic, as he often was. Instead of giving up the idea, however, the conspirators merely postponed it. When I think that as I write these lines, just two years after the period I am describing here, most of these same men are indignant at the thought of the people violating the constitution to do for Louis-Napoléon precisely what they themselves proposed to do at that time, I find it difficult to imagine a better example of human fickleness or of the vanity of fine words such as patriotism and justice, with which men cloak their petty passions.

Clearly, we were no more certain of the president’s support than of the majority’s. Indeed, Louis-Napoléon was the greatest and most enduring danger for us as well as for the Republic.

I was convinced of this, yet when I was able to study him closely, I clung to the hope that we might obtain some significant influence over him, at least for a while. Indeed, I soon discovered that although he received the leaders of the majority frequently and listened to their advice, sometimes accepting it and even plotting with them when the need arose, he was nevertheless quite impatient under their yoke. It humiliated him to be seen as their pawn, and he secretly longed to escape their tutelage. This gave us an opening and a certain influence over him because we too were determined to outmaneuver them and prevent their gaining control of the executive branch.

Furthermore, I did not think it impossible that we might partially enter into Louis-Napoléon’s designs without abandoning our own. When I reflected on that extraordinary man’s situation (extraordinary not for his genius but for the way circumstances had elevated his mediocrity to such heights), what struck me was the need to ease his mind by feeding him grounds for hope. I seriously doubted that such a man could be banished to private life after governing France for four years, and I thought it quite fantastic to think he would agree to depart of his own free will. Indeed, I thought it would be difficult to prevent him from embarking on some dangerous adventure during his term in office unless one could find an appealing way to divert or at least restrain his ambition. That, in any case, was what I tried to do from the outset. As I told him:

I will never help you overthrow the Republic but will gladly work with you to assure you an important place within it, and I think my friends will all eventually agree to do the same. The Constitution can be revised. Article 45, which prohibits the reelection of the president, can be changed. That is a goal we will gladly help you to achieve.

Moreover, since the prospect of revision was dubious, I went further and suggested to him that in the future, if he governed France tranquilly, wisely, and modestly and limited himself to becoming the nation’s chief executive rather than its master or corrupter, he might at the end of his term be reelected by virtually unanimous consent in spite of Article 45, since the monarchist parties might not see his continuation in power for a limited time as incompatible with their hopes, while the republican party might see a government like his as the best way of familiarizing the country with republican rule and even fostering a taste for it. I told him this in sincere tones, because I was sincere when I said it. Then as now, my advice seemed to me in the best interests of the country and perhaps in his best interests as well. As was his wont, he listened to me carefully without giving any hint of the impression my words made on him. Words addressed to him were like stones tossed into a well: one could hear the sound they made, but one never knew what became of them. In any case, his approval of me seemed to increase over time. Of course I tried hard to please him insofar as was compatible with the public good. Whenever he recommended an honest and capable individual for a diplomatic post, I was quick to find a place for him. Even when his protégé was not very capable, I usually acquiesced, as long as the post was unimportant. But the president generally reserved his recommendations for scoundrels who had supported his party in the past out of desperation, not knowing where else to turn, and he felt obligated to reward them. Or else he tried to place what he called his people—men who were for the most part intriguers and rogues—in important embassies. In such cases I would go see him and explain the regulations that stood in the way of his wishes or the moral and political considerations that prevented me from complying. Sometimes I even hinted that I would resign rather than give in. When he saw that my refusal involved no personal grudge against him or systematic wish to resist his whims, he either gave in without lasting rancor or put the decision off until later.

I did not get off so easily with his friends. They were like dogs ripping apart their prey. They assailed me constantly with their demands, so importunately and rudely that I often felt like throwing them out the window. I nevertheless sought to restrain myself. Once, though, one of them, an authentic refugee from the gallows, arrogantly asserted how odd he found it that the prince lacked the power to reward those who had suffered for his cause. “Sir,” I replied, “what would be best for the president of the Republic would be to forget that he was ever a pretender and remember that he is here to take care of France’s business, not yours.” What finally put me in the president’s good graces was, as I will describe later, my firm support for the Rome expedition, at least until he went too far and his policy became unreasonable. At one point he made my standing with him quite clear. Beaumont, during his brief stint as ambassador to London at the end of 1848, had said some very insulting things about Louis-Napoléon, who was at that point a candidate for the presidency, and this had caused quite a bit of irritation when Beaumont’s remarks were reported back to him. After becoming a minister, I tried on several occasions to raise the president’s opinion of Beaumont, but I would never have dared propose him for a post, as capable as he was and as eager as I was to have him. The post of ambassador to Vienna came open in September 1849. It was at that juncture one of the most important diplomatic posts we had because of our discussions with Italy and Hungary. The president himself said to me: “I propose to give the Vienna embassy to M. de Beaumont. I have had every reason to disapprove of him, but I know he is your best friend, and that is enough to persuade me to have him.” I was delighted. No one was better suited for the post than Beaumont, and nothing could please me more than to offer it to him.

My colleagues were not all as assiduous as I was in seeking to win the president’s favor without betraying my convictions or my duties.

Against all expectation, however, Dufaure always behaved toward the president precisely as he should have done. I believe he was half won over by the simplicity of the president’s manners. Passy seemed to take pleasure in annoying him, however. I think he felt he had debased himself by becoming the minister of a man he regarded as an adventurer and often sought to assert his superiority through impertinence. He unnecessarily opposed the president on frequent occasions, rejecting all his candidates, browbeating his friends, and rejecting his advice with ill-concealed disdain. The president therefore sincerely despised him.

The minister in whom the president had the greatest confidence was Falloux. I always believed that Falloux had won him over by giving him something more substantial than any of the rest of us could or would offer him.

Falloux, who was a legitimist by birth, upbringing, social connections, and taste, ultimately belonged exclusively to the Church, as mentioned earlier. He served legitimism but did not expect the legitimists to win; through all our revolutions he sought nothing other than a path by which the Catholic religion could be restored to power. He remained in government only to look out for the interests of the Church, and as he admitted to me with cunning candor on our first day in office, he did so on the advice of his confessor. I am convinced that Falloux saw from the beginning how Louis-Napoléon might serve his designs. He quickly realized that the president would become the Republic’s heir and France’s master, and from then on his only thought was how to use that inevitable outcome in the clergy’s interest. He had committed his party to the government, but not his person.