The yellow Cressida cruises slowly down the dirt road and comes to a halt on the grass beside Wemmer Pan.

It’s afternoon; it’s quiet; it’s secluded. The battered car seats are lowered, clothing that gets in the way is unceremoniously stripped off.

It’s high tide for the libido, riding the waves on the Cressida’s aged shocks.

The car rocks.

Suddenly, the door is jerked open, the man is pulled out of the car and shot with his own pistol, a 9mm Parabellum Star m30. He falls on his stomach beside the car and lies in a twisted heap in his bright green-and-yellow soccer top, his trousers around his ankles, one arm outstretched, the hand in a supplicating gesture.

Minutes later he is dead.

His life has ended in a climax.

Then it’s the woman’s turn. She is raped and her head viciously beaten to a pulp. She lies in the winter grass in her blue-and-white polka-dot dress.

In the air lingers the bitter smell of blood and the muskiness of semen.

Later the police knock on a front door in Mayfair. They are the bearers of gruesome tidings. “I’m sorry, ma’am,” the detective begins sympathetically, “your husband has been murdered. Together with a woman. We found them at Wemmer Pan …”

The woman bursts into tears and weeps hysterically in the doorway.

Piet unfolds the Grandpa with practised fingers. His fingers are slender, like those of a pianist.

He clears his throat, opens another docket in that overcrowded mind of his.

“In June 1997 the station commander at Booysens informed me that there was a tendency at Wemmer Pan in the south of Johannesburg. Interestingly, the murders took place only on weekends, somewhere between Friday evening and Sunday afternoon.”

Someone’s macabre weekend pastime, in other words.

When Piet took over the investigation, about fifteen women had been murdered in the vicinity of Wemmer Pan in a little more than a year – the murderer was clearly very active. Piet knew at once that this was his next serial killer. The hunt was on.

By then, Piet had established a firm reputation as an investigator of serial killings. The media had taken note of him; they were writing about the solemn detective in his immaculate suits, the detective who never threw in the towel.

“Little did I know what was waiting for me,” Piet mutters under his breath.

And little did this slight detective know, when he dropped me off at the airport on New Year’s Eve 2007, what would be waiting for him during the twelve months to follow.

One morning in May 2008 Piet worked up the courage to tell Esmie that he couldn’t live with her any longer and he wanted a divorce. She stared at him, speechless, while he threw a few items of clothing into a travel bag. Later, in an interview with The Star, Esmie said she wasn’t surprised. She even helped him carry his bags to the bakkie.

When he drove through the gates of the security complex, he felt only one emotion: relief. “I was so relieved that I had finally taken the step, that I was finally on my own, that I no longer had to live with the fear of her next outburst. Because that was terribly hard for me.

“I was only about three blocks away when she phoned, swearing incessantly. Verbal abuse, I’m telling you.”

That call, Piet remembers, was the final confirmation he needed that he couldn’t stay with Esmie for a moment longer. The sudden certainty comforted him.

He sighs. “Worst was when she would wake me in the small hours, screaming and cursing for no reason at all. I’m sure even the neighbours could hear every damned word.”

The last straw was when she started threatening to set Piet’s Mercedes and Bantam bakkie alight.

“I was forced to remove the vehicles from the premises,” Piet says. Though clearly upset, he still uses the judicial jargon that has become part of his personality. Forced. Remove. Premises.

The Mercedes that had come as part of Piet’s remuneration when he was promoted to director in 2007 had become an issue between them, he tells me. Esmie had refused point-blank to drive in the car with him. “She said that when we drove in the Mercedes, I considered myself superior to her because I had become this hot-shot director.”

For Esmie, perhaps, the Mercedes became a symbol of her husband’s estrangement from her, of the rapid disintegration of their marriage. So she expressed herself in the only way she thought possible: I refuse to drive in it with you. I’m not a part of your fancy new life. You’ve left me behind. You’re riding this wave of success on your own.

“That’s sad,” I tell Piet.

At first it’s as if he doesn’t hear me. Then he shakes his head slowly. “There’s no love left between us,” he says. “I don’t hate her, but I despise the things she’s done to me.”

I glance furtively at Piet. He does seem more relaxed these days, as if there’s a huge weight off his mind.

The end of the road for the passengers of the pale-yellow Cressida.

But there’s something else.

The moment I saw him waiting for me in front of the airport building, in exactly the same place where we had taken our leave of one another on New Year’s Eve a year ago, it was as clear to me as the red-and-white Avis sign on the pavement that something was different about Piet. Very different.

The reason for that difference stood beside him. Tall, blonde, wearing a dress in a soft floral print and a hesitant smile.

“Elize Smit,” he told me, introducing her a bit awkwardly.

She left us alone with a plate of snacks in Piet’s brand-new home, a townhouse in an upmarket development in Ruimsig, Roodepoort. He moved here in September 2008, after staying with his sister and her family in the same complex for a few months.

As Elize left us, Piet followed her appreciatively with his eyes. Where she fitted in, I wasn’t sure. He didn’t say.

Piet digs around in a docket and pulls out a photo of a woman. Her turquoise T-shirt is pulled up high. A muti cord, which, according to Zulu tribal custom, was supposed to have protected her, lies uselessly under her pale breasts. Her head is turned away, as if she wants to avert her gaze. Her face is unrecognisably battered.

“She was raped. Then her attacker picked up a large rock and repeatedly threw it onto her face.”

That was what Piet’s client did to single black women. He was more than a murderer. This was more than a murder.

As is so often the case, Piet explains to me, the murderer seemed to fear that his victims would be able to identify him if their eyes were left open, even after death. In photograph after photograph they lie there, their eyes surreally covered by an item of clothing.

As was Piet’s habit, he approached this new murder mystery by applying Byleveld’s First Rule of Detection: start with the basics.

“Some investigators run around in circles, looking for evidence. I sit down calmly and reason things out step by step. Without knowing what the motive was, you can’t solve a murder case. Motive is everything.”

Then he connects the killings one by one until he has a complete picture.

Piet is not the kind of detective that visits a murder scene only once and then that’s it. He is so obsessed with detail that he will hang around a murder scene for days. One particular piece of evidence was found, doing just that.

“A week after the body of one of the Wemmer Pan victims had been removed, I found a Kleenex on the scene that had the DNA of the murderer. One Kleenex, one week later … what are the chances? The wind could have blown it away.

“I’ll probably return to the crime scene a thousand times. I’ll sleep there. Camp there. Smoke with the locals. The smallest detail – like an old cigarette butt – could be the link to the murderer in the end.”

It’s his acute ability to observe that counts in his favour, he believes. He can make deductions at the scene, place himself in the murderer’s shoes. “I try to find out as much as possible about the victims. What kind of work did they do? What were their movements? Their routine? Look, a victim doesn’t just come walking up to a killer. What exactly led to the two of them to be in the same area? Gradually those facts lead me to the murderer’s modus operandi.”

Every clue slots into place somewhere. As the investigation progresses, Piet works with the individual clues, until the bigger picture emerges.

While Piet’s investigation of the Wemmer Pan murders was underway, with a woman being murdered almost every weekend, he was suddenly confronted with a new string of murders, also in the vicinity of Wemmer Pan. This time, however, couples were being brutally murdered among the bushes and trees.

The area was well known as a place where men took their lovers for “clandestine meetings”, as Piet puts it. The murderer would overpower the couple while they were having sex.

“Caught in the act, one might say. The poor people didn’t know what hit them. He sometimes forced them to have sex while he watched.”

Without saying a single word, the murderer shot his male victims cold-bloodedly in the back of the head. He always took a shoe as a trophy. Only one. The women were forced to run up a nearby mine dump while he gave chase, swearing all the while, mostly in Afrikaans, interspersed with his favourite English words: “bitch” and “clitoris”.

Piet grins when he sees my expression. “Ja, this client gave them hell.”

When they reached the top, the women were forced to undress before he raped them. Those who resisted were promptly killed. Those who begged for their lives were sometimes spared if the killer was feeling magnanimous. To some he even gave the taxi fare that would get them home – R4,50. A hand-out from a killer.

Those who got away described him as small but very strong and extremely aggressive. Some of the women were raped three times.

Piet grins. “He boasted to one of his victims about all the murders he had committed. Then he asked to see her again – he actually tried to date her!”

With the murder of the couple in the yellow Cressida, the killer had come into the possession of a pistol and he’d upgraded his method from bashing in heads to shooting to kill. Head shots, mostly.

Almost every weekend there was an attack. The investigation began to take its toll on Piet. As always, he reproached himself after each murder, and on Saturdays and Sundays he would get into his car and drive endlessly around Wemmer Pan.

“I restricted my observation to during the day, because he never attacked at night.”

Frustrated, actually “totally fed up”, Piet decided to set up an ambush. He devised a plan. He and colleague Riana Steyn, posing as a pair of lovers, would wait for the murderer on top of the mine dump, in the heart of the murder area, in an unmarked car.

“We sat waiting in that blue Toyota Corolla for eight, nine hours.”

“Making out?” I ask.

He laughs huskily. “Heh-heh-heh, no, ma’am, nooooo.”

Piet had a gut feeling that they were going to catch the killer that day. That was why they sat there for so long. It was getting dark when they decided to call it a day. Piet was beginning to fear for Riana’s safety.

Just as they were pulling away, the men sent word by radio that a man was slowly moving up the mine dump, approaching the car.

“It was too late, too dark already, to stop to try to catch him. The moment had slipped through my fingers. I could have kicked myself. And I knew: tonight someone is going to pay.”

Piet alerted his men: There’s going to be hell to pay, the murderer is going to take revenge.

His feeling was spot-on, he says wryly.

Months later, in the cells, the murderer told Piet just how furious he had felt when he hadn’t managed to get to him. He had known he was a policeman and had wanted to kill him. He was like someone on drugs, high on pure anger. As he later explained to a psychologist: “When I’m angry, I can’t even speak, there are no words in my mind.”

The attempted ambush changed the way the killer behaved. That night was the first time he attacked at night. What was more, he suddenly moved away from the area in which he had usually operated.

He set off for Langlaagte, and it was there, some time later, that he came across Samuel Moleme and his girlfriend, Catherine Lekwene, lying in each other’s arms. He shot and killed Samuel and raped Catherine twice before letting her go. He had shot Samuel so unexpectedly, so fast, that when the victim’s body was later discovered, his cap was still on his head.

There was a ZCC (Zion Christian Church) badge, Piet remembers, just above the bloody patch where the bullet had struck him in the heart. He too had had a muti cord around his waist. With this murder, however, the murderer had taken both Samuel’s shoes as trophies and, in doing so, deviated from his previous pattern, in which he had taken only one.

Five kilometres further away, in Claremont, he found his next victims having sex in some bushes. He shot Pieter John du Plessis, raped his friend Sara Lenkpane, and shot her as well. The police found Pieter’s body in a foetal position next to Sara’s. Her blue dress was hiked up to her hips. Both had been shot in the head. Again, the killer had taken both shoes of his male victim.

A kilometre further, his bloody path crossed that of fifteen-yearold Lelanie van Wyk and her boyfriend, Martin Stander (19). They had been on their way home from a nightclub in Delarey where Martin was a disc jockey. At half past eleven that night, people had seen them dancing and having a good time. The couple had allegedly gone behind an industrial building for some “alone time” before Martin planned to take Lelanie home.

The murderer ordered Martin to take off everything except his underpants. This was a strange turn of events – he had never made his male victims undress before. He shot Martin in the head and took his clothes and shoes.

They were his third pair of shoes of the night.

Martin lay on his stomach, his slim, boyish body clad only in red underpants and brown socks. Blood was flowing from his ear.

The killer took the terrified Lelanie some distance away, ordered her to undress, raped her and shot her in the head as well. Around her neck was a delicate chain with a small dolphin and a yin-yang symbol, on her hand the stamp of the club where they had been seen earlier that night.

But the killer’s bloody trail did not end there.

A victim’s muti cord.

Michael Mkhize is shot through the neck, but survives.

The murder scene of Lelanie van Wyk and Martin Stander.

The place where Martin Stander was found.

The Minnie Mouse tattoo on Lelanie van Wyk’s shoulder was used to identify her.

The nightclub stamp still on Lelanie’s hand.

The killer continued in the direction of Main Reef Road, where just before dawn he stopped a taxi in Langlaagte. The taxi driver, Michael Mkhize, took him nearly all the way to his home in Overton before he was forced at gunpoint to drive to an industrial area. He was shot in the neck and left for dead. Miraculously, he survived and was later able to give evidence at the trial. This time the killer took only one shoe.

The new day dawned, scattering shards of light across the mine dumps.

Apart from the taxi driver and the girl that the killer had allowed to go, all the victims of that murderous night lay lined up in the morgue. All five of them.

“The staff had their hands full …” Piet says grimly. “To this day I feel guilty about that night.” Piet shakes his head. “I could have prevented it. If only I hadn’t driven off, I could have saved the lives of five people.”

Details of the murderous orgy were blazoned across the front pages of the papers, and fingers were inevitably pointed. Where were the police? Why couldn’t they catch this monster?

Piet started to smoke even more, ate even worse, lay awake even longer at night. His asthma was getting out of control. Eventually he had to start using an oxygen cylinder at night.

“Everyone was on my case. The pressure was tremendous. Everyone, from the media to my seniors, said the same thing: catch this man, and catch him quickly.”

After that night of vengeance, it was as if the murderer’s thirst for blood could not be quenched. He struck almost every weekend, and had returned to his familiar stomping ground. He continued to shoot his male victims at point-blank range, without saying a word, and always taking one shoe as a trophy.

As obsessed as this man clearly was with killing, just as obsessed was Piet with catching him.

Piet and his team began a relentless observation of the area, spoke to anyone they thought might have seen something, and moved around the area day and night, looking for possible clues. But they found nothing.

Then the next murder would occur. Another missing shoe, and Piet would know: it’s him. He’d find the 9mm cartridge cases and he’d know: it’s him.

“Hell.”

Had such events happened in Europe or America, the police force would undoubtedly have been able to deploy more than a hundred detectives to work on the case. But this was Africa. Here it was just Piet, his Benson & Hedges and his troika of helpers.

An elderly Portuguese man, Gerhard Lavoo, had the habit of riding his bike for exercise every afternoon on a path through the trees beside Wemmer Pan.

“The murderer waited for him, casually shot him in the back as he was riding by and took his bike. Just like that.” Piet shakes his head.

“The cartridge cases found at the scene looked as if they had been fired from the weapon used by the Wemmer Pan serial killer. I realised we were dealing with a superkiller, who kept changing his modus operandi.

“I mean – shooting and killing an old man for a bicycle! The entire sexual motive went down the chute.”

To confound the profile even more, the murderer would randomly spare his victims’ lives. At the La Rochelle soccer field adjacent to Wemmer Pan, he had allowed a couple to leave after he had wounded the man and raped the woman twice. This was the couple that was later able to identify him from a line-up.

“The semen was also linked positively to him,” says Piet. “In a way, his semen was also the seed of his downfall.” He gives a wheezy laugh. “Time and again it linked him to a rape.”

But still the killer remained at large, and the number of victims continued to rise.

On 19 December 1997, an excited couple’s outing to the circus ended in tragedy. Bongani Khama, a security guard, and his girlfriend, Ntombifuthi, were on their way to the circus in Regent’s Park. They were walking through a park when Khama heard a shot being fired. At first he thought it was a firecracker but then he felt a warm sensation in his back and an acute burning pain. He fell to the ground.

The murderer squatted beside him and in broken Zulu asked for money. Khama gave him the R180 he had for their circus tickets, while he kept praying: “God, what is going to happen to me? What is going to happen to my family? Spare me, please.”

Just before he lost consciousness, the killer told him that his girlfriend was going to die.

She did.

But Bongani’s prayers for his own survival were answered.

In Piet’s townhouse, the telephone rings. He frowns. It’s Esmie. No, he can’t come to see what’s wrong with the lights today, he tells her firmly. No, he can’t come tomorrow either, he’s busy. She continues talking, the pitch of her voice rising. He answers curtly. After a while I hear her voice become even shriller. He cuts her off, and looks at me.

“Where were we? Oh yes, and then the breakthrough came at Wemmer Pan. Out of the blue.”

Someone from the area, a vigilant member of the public, became suspicious of a man who was hanging around a hotel without actually drinking or eating there. He gave the police a description and said that he thought the man might be having a relationship with a certain woman there.

The description matched the picture that, from the accounts given by survivors, Piet had by then formed in his mind: a small, thin man, usually clad in neat green trousers and a grey jersey with the faded impression of a face on it.

“That was when things began to develop. I found out the girlfriend was Angelina Tlapane, and she worked at a dog parlour.”

Early on the morning of 23 December 1997, Piet and his partners began their surveillance of Tlapane. They followed her. At about eleven o’clock, she got into a taxi and travelled towards Jeppe. Near the railway station she got out and waited on the corner of John Page and Pine Road.

A small man clad in green trousers and a grey jersey came sauntering along. Piet knew instantly: this was his man.

The team pounced, arresting the man on the spot. In his right trouser pocket they found a cartridge. “I read him his rights and told him he was suspected of murder and rape. You can’t even begin to imagine what pleasure I got from that.”

The man didn’t say a word.

Six months. That was how long it had taken Piet to catch one of South Africa’s cruellest serial killers. He had shot twenty-three people and raped fifteen women.

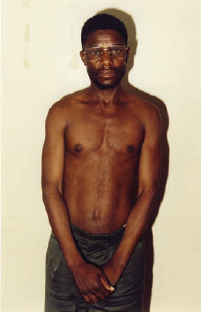

Cedric Maupa Maake.

A Pedi, thirty-two years of age. Handyman, suburban gardener. Serial killer.

As one journalist from Beeld described him during the trial, Maake was a small, thin, fresh-faced young guy, someone you wouldn’t hesitate to employ if he came knocking on your door on a Saturday morning.

On the way back to Brixton after he had been arrested, Piet watched Maake in the rear-view mirror. He saw his lips turn white.

“Do you feel all right?” Piet asked. Silence.

After an arrest Piet always watches the suspect, taking note of the way the suspect speaks to him, looks at him, or doesn’t look at him. Piet is able to detect the slightest sign of nervousness – how the suspect keeps swallowing, for example. “I see the person. I immediately know if the person I’ve caught is the right one.”

Cedric Maake’s white lips gave him away.

At Brixton, Maake asked to see his wife. “I’ll arrange it,” Piet said. Mmm, his weak spot, Piet thought. But his face showed nothing.

In the meantime, Piet knew very well that he could detain Maake for only forty-eight hours – the window period during which he would have to collect enough evidence to charge him.

First he arranged for a blood sample so that it could be compared to the DNA profile the police already had of the murderer. The technicians at the forensic lab in Pretoria worked right through Christmas so that they could have the results ready before the deadline was up.

Only hours before the cut-off time, Captain Luhein Frazenburg of the forensic division phoned with the news: the DNA matched. It was the same man.

“Suddenly Christmas had come for me too!” Piet says.

But Piet’s client was in no party mood. Neither were the two policemen who had to guard him at Brixton. Piet grins. “The shit was literally flying, and they had to duck to avoid it! Maake was throwing his own faeces at them, screaming like a stuck pig.”

As with Mazingane, Piet had to rush to Brixton in the middle of the night to calm the man down.

When he arrived at Maake’s filthy cell, Piet asked casually. “Can I get you a cooldrink? You might as well know you’re not getting out of here. You can do what you like but it would be better not to upset the people around here.”

Piet then offered him a cigarette. No, Maake shouted, he doesn’t smoke. Nevertheless he took the cigarette and put it behind his ear before breaking it into pieces. Piet stood there, watching, impassive.

“I spent two, three hours with him. He swore at me and carried on, repeating over and over that he had no idea what I was talking about.

“Later I said: I’ve been so kind to you. I fetched your wife, and I’ll bring her again if you want me to. And your mother …”

Maake really cared for his mother. Piet had learned that earlier from Maake’s wife. He used this information to calm Maake down.

If you talk to Piet’s colleagues, they’ll all mention Piet’s endless patience with suspects. Other investigating officers often become irritated, but not Piet. He seldom gets angry, but when it does happen, it’s highly effective. He uses anger only to get results. Piet Byleveld is one of those rare people who are in full control of their emotions.

The next day, DNA results in hand, Piet confronted Maake in his office.

“Cedric, I know it’s you who killed all those people at Wemmer Pan, raped the women and did all those things.

“He watched me in silence for about a minute. The next moment he said, almost proudly, ‘Yes, I did it. It was me.’

“He admitted it. Right there in my office.” Piet smiles, savouring the moment once more.

“The thing is, serial killers won’t stop until they are caught. Actually, they want to get caught. And it’s my job to catch them.”

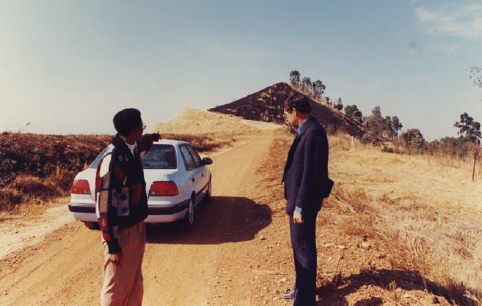

Piet arranged for Maake to point out the murder scenes in the company of an independent officer and an interpreter. “It’s important to do it immediately, before the suspect gets cold feet,” says Piet.

Maake took them to more than forty sites, including the one where he had shot “the white man” (Gerhard Lavoo) beside Wemmer Pan for his bicycle.

The clothing and shoes he had taken from his victims were stored with his mother in Giyane, near Tzaneen in the former Northern Province, he told Piet.

Mazingane had left the shoes of the women he raped neatly next to their bodies.

Cedric Maake after his arrest.

A handbag found at a murder scene.

One of Maake’s victims found lying in a foetal position.

Maake often removed his victims’ shoes.

Maake points out a scene to Piet.

Maake generally only took one shoe from the male victim.

“Do all serial killers leave messages and clues for their investigators, as profilers and detective series like CSI would have us believe?” I ask.

“With respect, that’s nonsense,” Piet says brusquely, keen to put paid to the idea. “In not one of my cases did that happen. It’s a theory that is encouraged for the purpose of sensationalism.”

Piet sniffs at such gimmicks. “I never work with a profiler. I make sure of the true facts, as they appear in front of me, ma’am. Facts. They give more than enough information.” In spite of the stuffy Piet-speak, his eyes are twinkling mischievously.

He takes a piece of biltong from his friend’s snack tray and lowers it furtively to Seuntjie, who is lying at his feet under the table. Meisie, the other fox terrier, lives with Esmie.

Dogs, it appears, also get divorced.

On 29 December 1997, Piet and his team set off with Maake for Giyane.

It was another typical soft-soap trip of Piet’s, with chats about sport, offers of a radio in his cell, and a copy of the Sowetan lying on the seat for the suspect to read in the car.

When they finally arrived at their destination, they found in Malekgolo Maake’s township house a pile of clothes and shoes. Here was her son’s macabre loot.

Malekgolo was clearly devastated when she saw her son, Cedric, in police custody. Piet left them alone for a while.

Malekgolo had been the first wife of Cedric Maake’s father. He’d got married again, and after that, Cedric and his mother had played second fiddle. The cattle had been divided up and the second marriage had left Cedric’s mother poorer.

“It broke Cedric,” says Piet. “He told me that he hated his father with a passion.”

On their way back that evening, Piet and Maake’s conversation in the car was forthright and easy.

Then, out of the blue, Maake offered to show Piet where he had hidden the pistol.

It was late, about half past ten, when they stopped in the Wemmer Pan area. It was also pitch-dark and it had begun to rain. Maake led the way, with Piet and the two sergeants in tow. They felt their way past a flattened mine dump, until they were behind a tree.

“You won’t believe it but even in that darkness he went straight to the spot. Suddenly he bent down. Luckily I was on guard. Bloody hell! He was going to surprise me, grab the pistol and shoot me.”

Piet ignored Maake all the way back to Brixton. No more chitchat. In the boot, safe in a plastic bag, was Exhibit 1: the pistol.

“When the report came back from ballistics, I knew there was no way he was going to get out of it. Victory.”

By this time Piet had already “got inside Maake’s head” and found out everything he could about him. Now he knew even the smallest details about the killer and how he operated, yet very little was known about Maake’s childhood. He came from Thohoyandou in Limpopo Province. He went to school until standard seven before coming to Gauteng, where he did painting and gardening jobs. His employers trusted him implicitly.

“One of his brothers is a police sergeant. Interesting, isn’t it? The same home, the same circumstances. But that very brother later offered me a R500 bribe to help Cedric.”

Maake had met his wife, Sophie, in Giyane. When he discovered that she’d had affairs with other men, the fat was in the fire. He discovered that she’d had sex with them on a nearby koppie. That was why he later chased his victims up mine dumps before raping and killing them, Maake told Piet.

While he was in detention, Maake would intimidate the policemen at the Brixton charge office. He unnerved them to such an extent that they refused to speak to him and even asked the station commander to send him straight to prison.

The homeowners at 57 Forest Street, La Rochelle, where Maake and Sophie had been living in the garage, were frightened out of their wits when they learned that the “nice Cedric” they knew was actually the Wemmer Pan serial killer.

He had been a perfect, quiet tenant. In his room, detectives found more 9mm cartridges.

They found Sophie there too. The poor woman didn’t have an inkling.

Piet laughs, a belly laugh. Yep. Serial killers look like … anybody. Your gardener. Your taxi driver. Your husband. They conceal their underlying aggression very well; they usually work alone; they take no one into their confidence; they have memories like elephants and are extremely cunning.

Trying to catch one, Piet says, is like playing chess against a grandmaster. And catching one … He draws long and deeply on his cigarette.

And then, with Maake a new member of Piet’s exclusive group of prisoners, the Piet Specials, one of the biggest breakthroughs in Piet Byleveld’s career was lurking murderously around the next corner.