Chapter 5

OUTSIDE THE WIRE: PHUOC TUY

Travelling outside the wire throughout Phuoc Tuy is relatively simple. The arterials are all well marked and guides very rarely get geographically misplaced. I have even used a war-era map and been able to get from one side of the province to the other with little trouble. Most groups base themselves down at Vung Tau while they spend a couple of days touring the province. The areas they will normally visit are Nui Dat, The Horseshoe, the Memorial Cross site at Long Tan; they will also do a circuit around the mountains at the southern end of the province including the Long Hai Hills, and the Nui Thi Vai and Nui Dinh Mountains. If they have time, groups can also venture further afield to Xuyen Moc and do a circuit up to Binh Ba north of Nui Dat, and then motor west across the Hat Dich area and turn south back down past Long Son Island to Vung Tau.

Ba Ria–Vung Tau (Phuoc Tuy) Province

Situated about 40 kilometres south-east of the former Saigon, Phuoc Tuy Province—now known as Ba Ria–Vung Tau Province—was the area the Australian Task Force were responsible for as part of the Allied effort against the Viet Cong. The province covered approximately 2500 square kilometres, consisting of coastal plains with sand dunes to the south, the Mekong River Delta with mangroves and swamps in the south-west, and three isolated jungle-covered mountain groups to the south-east, with Ba Ria as its capital. The province was chosen for a number of reasons. It was strategically important as it contained the port facility of Vung Tau where Australian logistics could be brought ashore, and the vital Route 15 arterial road between the port and Saigon. Although heavily controlled by the Viet Cong, the province could also be contained using Australian counter-revolutionary warfare techniques, and the terrain—mostly flat and covered in jungle—suited the Australian forces and their military structure for operations.

Phuoc Tuy Province was an operational backwater compared to the northern provinces of South Viet Nam near the demilitarised zone (DMZ) on the 17th Parallel border. However, it harboured fewer suspected enemy than the regions to the north, and was an area where the Task Force could manage its own military affairs to a certain degree and work in accordance with Australian Army doctrine and tactical procedures.

The province has changed dramatically since the war ended. Returning veterans will notice the changes to the village structures, the widened and bitumened roads—some of which are now toll roads—and the overall increase in village and population density. They will also have to buy new maps as many of the road and street designations have changed—and in many cases throughout Viet Nam, towns have also been renamed, usually to honour a local war hero or represent a Communist victory.

Once the veteran enters the old province, whether by road down from Ho Chi Minh City, or by the much-preferred hydrofoil ferry down the Song Sai Gon (Saigon River), things will begin to look familiar, and memories will start flooding back. The major geographical features have not changed, although since 1993 the vegetation on top of the Nui Thi Vais has started to regrow after decades of being barren as a result of defoliant spraying.

Vung Tau

The first place many veterans saw in the province if they came by sea aboard HMAS Sydney—the converted aircraft carrier that operated as a troopship and stores carrier—was the port and resort city of Vung Tau, about 130 kilometres south-east of Ho Chi Minh City. The wreck of a ship was prominent at Cap St Jacques, but it has long since gone to the scrap-metal yards. The city is once again a seaside resort town, and attracts flocks of residents from Ho Chi Minh City on weekends, especially young courting couples on motorcycles.

During the war, when the Sydney arrived in the port the soldiers were most often ferried ashore by American Army Chinook helicopters. For most Australians it was the first time they had ever seen one of these huge machines—which one American compatriot once described most colourfully as ‘two palm trees fuckin’ in a bucket’—let alone fly in one. Once on board, the American crewmen would ensure that the soldiers’ rifles were pointed down towards the floor so that an accidental discharge didn’t take out the vital hydraulics that kept those two ‘palm trees’ operating. Bill Kromwyk recalled his maiden flight in one of the huge noisy machines:

I just remember looking around at everybody’s faces and—with the exception of Bob [Bettany]—how green and bewildered they looked. It was a whole new experience; here we are in Viet Nam. And then I looked at the American gunners on the doors and the pilots—there were about five crew—and they were sort of hardened and had a laid-back sort of look. And I thought, ‘My God, we certainly are green compared to these guys. Just look at them.’ I felt like a really green soldier.1

Vung Tau was a relatively secure area; there was little direct threat from the Viet Cong by day, and only occasionally by night. Any enemy activity was usually in the form of sporadic rocket attacks or small-scale ground attacks on Regional Force or Popular Force outposts in the local area.2

Mortarman Private Garry Heskett was flown ashore in a Chinook and said he experienced feelings of dread, admitting he had ‘a feeling of slight nervousness, anticipation and being super-alert, believing that the enemy were hiding behind every bush and tree’.3

Bill Kromwyk was doing his National Service with 6 RAR on their second tour of duty in 1969–70, and came ashore from the HMAS Sydney by other means:

We were anchored off Vung Tau and then the landing craft came and got us. We went from there in the landing craft to land on Vung Tau. We climbed down into the landing craft and we couldn’t see anything, all we knew was that we were heading towards Vung Tau and didn’t know what to expect. We were told that probably nothing will happen but, just in case, be careful. I don’t know if we even had any ammunition! Of course nothing happened. I always remember the big ramp coming down and there were all these officers standing there waiting for us. There was no enemy. So we piled off and we had to march to the airstrip, and the [RAAF] Caribous took us to Nui Dat.4

When 5 RAR first arrived in country in 1966 they were to be part of the 1 ATF. The battalion main body (about 700 men) was sent down to the sand dunes of Back Beach to acclimatise and prepare for Operation Hardihood, which was to be conducted in close coordination with American units to secure the Task Force base area.5 The sand dunes were hot, windswept and not at all inviting. There was a total lack of facilities and the equipment the soldiers needed to prepare for their immediate task.

Captain Peter Isaacs stood on what is now a Viet Cong martyrs’ monument—where once the 1st Australian Logistic Support Group (1 ALSG) Officers’ Mess stood—and looked down at the four-lane toll road leading to Ba Ria, and several hotel resorts under construction near the beach. He commented, ‘I think it looks ghastly.’6 Not everyone has that same opinion and many are glad to see the area forging ahead, fuelled in part by massive off-shore oil and gas exploration projects that are now bringing energy resources and wealth into the area. Peter reflected:

I’ve wandered around the world since those days and the development that’s gone on is typical of development that goes on which is unplanned, haphazard. Some of the buildings are very good, and I certainly applaud the Vietnamese [for] the gardens that they have developed and so on. But Back Beach? Well, it was a stretch of sand, and it was as I expected it would be.7

Paul Greenhalgh recalled his most vivid memory of Vung Tau as:

Standing on the sand at the ALSG at Vung Tau . . . talking to the soldiers before Operation Hardihood. We flew in by choppers from Vung Tau and I remember going on a bit like a football coach, geeing them up and saying, ‘Here we go, here we go.’ And then there was a short [chopper] flight up to what was the Nui Dat area and landing. It was on; we were away.8

During their tour of duty soldiers would be given a few days’ R&C leave at Vung Tau. This was usually granted about six times during a one-year tour, if you were lucky, and was designed to refresh soldiers. Groups of about 100 or more could be accommodated at a time, and when the 1 ALSG rest centre was established at Back Beach it was called the Peter Badcoe Club after the posthumously decorated Victoria Cross winner from the AATTV. Soldiers were then billeted in a hostel in town, which was named ‘The Flags’ on account of Allied nations’ flags decorating the opposite street. The men were free for about 48 hours to visit the town dressed in civilian attire, and went unarmed—but also forewarned that the greatest danger they now faced was not the VC but VD. There were about 3000 bar girls plying their trade, and sexually transmitted diseases were prevalent; it was an offence if a soldier failed to take precautions and became a casualty.

So, it was a case of taking it easy and relaxing by swimming, drinking, boating, drinking, dining out and drinking, and occasionally taking in the cultural delights of the town such as bars, saloons and hotels. The Military Police were kept busy and generally most of the soldiery who went to Vung Tau had a good time—if they could remember it. The officers were billeted at the Grand Hotel, which sat on Front Beach facing the South China Sea and had a luxurious beer garden, a reasonable restaurant and of course the obligatory dimly lit bar, where exorbitantly priced drinks were dispensed by hostesses who insisted on being bought a ‘Saigon tea’, which was a method of extracting good money for worthless coloured water.

A popular ditty that circulated at the time has now reemerged on souvenir items ranging from T-shirts to stubby coolers, which are boldly emblazoned with versions of these words:

Uc Dai Loi, he cheap Charlie,

He no buy me Saigon tea,

Saigon tea cost many many pee*

Uc Dai Loi, he cheap Charlie

(* for piastre—the local currency during the war)

Bill Kromwyk was asked if he remembered his visit to Vung Tau on R&C leave and he replied, ‘. . . sort of’. On his first visit back in 2001, Bill stayed in a hotel and walked around the town. ‘But it all looked different you know, I couldn’t quite recognise much of it—just around near the Grand [Hotel], I thought I remembered a little bit around there.’9

Ben Morris had reasons for not liking the town when he went down there on R&C leave with his platoon. The staunch Catholic explained:

To me Vung Tau was the Forbidden City. It was the place I didn’t really like going. I hated taking soldiers there on R&C because the bastards would all piss off. They’d all be in the out of bounds area and there was not much you could do about it . . . And invariably there were the one or two that you had to find and no-one in the world loves going back to Nui Dat to face the CO, missing a Digger or two.10

Ben has been back to Viet Nam three times now and has travelled from one end to the other. Of the modern Vung Tau he said:

Vung Tau is like a lot of Viet Nam. It’s moved on. It’s become cleaner. For a Communist country they believe in a lot of capitalism. I really am intrigued by the fact that here we are in a country that’s supposed to be Communist, and it’s raw capitalism.11

Fred Pfitzner was based in Nui Dat and only visited Vung Tau a few times during his tour of duty. Asked whether he was disappointed in the changes and being unable to recognise places, Fred replied, ‘Not at all. I would have been disappointed not to have seen great change.’12

Aviator Peter Rogers also went around town looking for landmarks and explained:

We had a sister unit in Vung Tau, the 54th Aviation Company, and they used to do maintenance for us, and if we went to Vung Tau we would stay with them. I went looking for their place and it was hopeless because the whole of Vung Tau has changed so much. I was also amazed at how big Ba Ria had become, monstrous.13

Ron Shambrook recalled his own reaction to visiting Vung Tau after 40 years.

When I first saw Vung Tau there was virtually nothing on those sand dunes, and now there’s high-rise resorts and apartments. In our tour [1966–67] we didn’t have the Badcoe Club complex and the swimming pool and ALSG, and no more permanent accommodation than tents. Towards the end of our tour, my company—Charlie Company—was given the task of going down and setting up some tents near the beach so we could cycle people through to help their health.14

When the 5 RAR pilgrims returned to Vung Tau in 2005 they arrived on the hydrofoil ferry service from Ho Chi Minh City. John Taske recalled his reaction as they entered the port:

It brought back a lot of memories. That was the view that I got because I came up on the HMAS Sydney with Charlie Company. And Back Beach—it was a disappointment from the point of view that it looked absolutely nothing like when we first arrived because all it was was just undulating sand hills—it was just tents among the sand dunes. And then when the monsoons came, it all got flooded out and then they had to level it and start again. But it was nothing like what I expected. But it’s beautiful; I’m delighted to see it develop.15

Roger Wainwright had the honour of commanding the first rifle platoon into the Back Beach area in 1966, which was then a mass—and mess—of empty sand hills. Roger was to a large extent the senior tactical person in the area, and here he recounts his journey after landing at Tan Son Nhut:

We got into a C-123 [Provider] and flew down to Vung Tau airstrip . . . We were put into the back of a cattle truck and went through what were essentially sand hills to Back Beach. There was no population around; we were going through winding little sand hills in that area. We spent the next couple of days essentially putting up [fencing] wire for the rest of the battalion so they could put up their hoochies. I was just racing around making sure the area was secure.16

The 5th Battalion did some refresher training as well as the normal acclimatisation runs and physical training to maintain fitness. ‘We were the only battalion that used Back Beach as a firing range, firing mortars and RCLs [recoilless rifles] and small arms out to sea at a few floating targets dumped out there by a boat.’17 It was far from pleasant—‘stinking hot and no shade, in the full sun on the sand, and problems with weapons’.

Asked how he felt when he was approaching Vung Tau again, Roger replied: ‘Coming down the river on the hydrofoil and just seeing Cap Saint Jacques and Little Hill and Big Hill in the background sort of gives you a few goose bumps and things like that.’18

Posing for a group photo in front of an Iroquois helicopter at the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City are, from left to right, Paul Greenhalgh, Peter Isaacs, Ted Heffernan, Roger Wainwright (rear), John Taske, Ron Shambrook (front), Tony White, Ben Morris and Fred Pfitzner. Photo courtesy Ron Shambrook

Standing in front of a B-52 bomb crater at the Fire Support Base Coral battle site, visiting veterans and partners listen to tour guide Garry Adams (third from left, pointing) describe the battle. Photo courtesy Paul Greenhalgh

At the risk of scaring the locals the 5 RAR pilgrimage group pose at Vung Tau in 2005, recreating a photograph taken of their group in 1966. Pictured are, from left to right: Dr Ted Heffernan, Dr Tony White, Ben Morris, Dr John Taske, Ron Shambrook, Roger Wainwright, Paul Greenhalgh, Peter Isaacs and Fred Pfitzner. Photo courtesy Paul Greenhalgh

The officers of 5 RAR’s first tour of duty pose for a Mess photograph in 1966 before leaving on Operation Hardihood to secure the Australian Task Force base at Nui Dat. Back row, left to right: 2Lt Jack Carruthers, Lt Roger Wainwright, 2Lt John Deane-Butcher, 2Lt Dennis Rainer, Lt Greg Negus, Capt Ron Boxall, Capt Ron Bade, Capt Bob O’Neill, Capt Brian Ledan, 2Lt Bob Gunning, 2Lt Trevor Sheehan, Lt John Hartley, Lt Ralph Thompson, 2Lt John McAloney. Centre row, left to right: 2Lt Harry Neesham, Lt David Rowe, Mr John Bentley (Salvation Army), 2Lt Ted Pott, 2Lt Mick Deak, 2Lt Finnie Roe, Lt Bob Supple, 2Lt John Cook, Capt Don Willcox, Capt Bob Milligan, 2Lt Terry O’Hanlon, 2Lt John Nelson. Front row, left to right: Chaplain Ed Bennett, Capt Ron Shambrook, Maj Bert Cassidy, Maj Bruce McQualter, Maj John Miller, Maj Stan Maizey, LtCol John Warr, Maj Max Carroll, Capt Peter Isaacs, Maj Noel Granter, Maj Paul Greenhalgh, Capt Tony White, Chaplain John Williams. Photo courtesy John Cook

The hydrofoil ferry service docking at Vung Tau has become a very popular way to travel to the seaside resort town. The hills of Vung Tau are visible in the background. Veterans will be hard pressed to locate any former R&C haunts, but the town still has the charm it held 40 years ago. Photo courtesy Ron Shambrook

The harbour and hills of Vung Tau peninsula welcome visitors to the seaside resort much as they did the many Australian soldiers and sailors who came to the harbour aboard the HMAS Sydney during the war. Photo courtesy Roger Wainwright

The 5 RAR pilgrimage group pose in front of the Nui Thi Vais (also known as the ‘Warbies’ or ‘Warburton Mountains’) on their tour around the old Phuoc Tuy Province. From left to right are Dr Tony White, Roger Wainwright, Peter Isaacs, Ben Morris, Fred Pfitzner, Ron Shambrook and Paul Greenhalgh. Photo courtesy Gary Mckay

The Nui Dat Medical Association, who had their first and last meeting in early 1967 prior to returning to Australia, celebrate and reminisce 38 years later very close to where they first downed some French pink champagne. Toasting the fact that they are still alive and upright are doctors John Taske, Tony White and Ted Heffernan. Photo courtesy Tony White

Paul Greenhalgh peers through the soft gloom of the rubber in Nui Dat near where 5 RAR established their original home in the Task Force base. Many veterans can place where their tent lines were during their stay in the area. Photo courtesy Paul Greenhalgh

A veteran walks back from his old tent lines in the northern sector of the former Task Force base at Nui Dat. The rubber is once again being worked and a factory now stands close to where the aircraft refuelling point was located. Photo courtesy Tony White

This road on the eastern flank of the Nui Dat base was once called Infantry Circuit and the three infantry battalions shared the avenue. Further south and beyond the photograph the road enters a prohibited zone where the current D445 Battalion is located. Photo courtesy Garry Adams

Standing amidst the ruins of what was the artillery command post at Nui Dat the 5 RAR tour group consult maps and memories as they survey the former Task Force base area. Photo courtesy Peter Isaacs

One of the few remaining signs of Australian occupation at Nui Dat is the ruins of the back gates to the Task Force base. Photo courtesy Garry Adams

Today, the local people ride their bikes through the Nui Dat rubber near the ruined gates. Photo courtesy Peter Isaacs

The 5 RAR pilgrims reflect on the battle at Long Tan in 2005 after a brief but moving informal remembrance service by several veterans who served in the battle area in 1966. Photo courtesy Rupert White

The Memorial Cross at Long Tan stands silent and sombre under the rubber canopy. The site has become iconic to veterans returning to Viet Nam and is one of only two foreign war memorials in the country. Photo courtesy Elizabeth Stewart

Embracing in front of the remains of The Horseshoe that had briefly carried the name Fort Wendy are Wendy Greenhalgh and her husband Paul, whose subunit was the first rifle company to occupy and begin fortification of the permanent fire support base in early 1967. Today the feature is being quarried for road base and is slowly disappearing. Photo courtesy Tony White

The view looking south-east from The Horseshoe with the edge of the Long Hais barely visible through an approaching afternoon thunderstorm. Photo courtesy Garry Adams

5 RAR Association President Roger Wainwright leaves a simple yet moving tribute to the officers and men of his rifle company who were killed in a mine incident outside the village of An Nhut on 22 February 1967. Photo courtesy Roger Wainwright

Villagers tend to their rice crops east of Ba Ria and close to the village of An Nhut, with the Long Hai Hills in the background. Photo courtesy Paul Greenhalgh

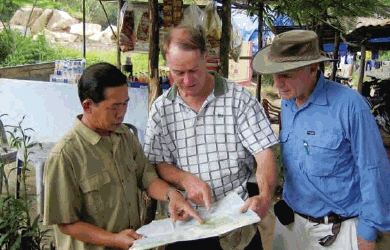

Comparing notes and war stories in the Long Hais are former D 445 Battalion officer Lieutenant Hoang Ngan, 5 RAR platoon commander Roger Wainwright and RMO Dr Tony White. Mr Hoang runs the Long Hai museum and a small café in the Long Hai Hills. Photo courtesy Rupert White

Shrapnel scars and bomb-fractured rocks adorn the entrance to a former Viet Cong hospital set amongst the caves and enormous granite boulders in the Long Hais. The area has been allegedly cleared of mines but visitors should exercise caution when moving off defined paths and tracks. Photo courtesy Garry Adams

Above: Looking south towards the Long Hai Hills and the former Minh Dam Secret Zone, which had a reputation as a place you really didn’t want to go if you were an infantryman. The Hills have once again recovered the growth that had been severely defoliated by chemical spraying. Photo courtesy Garry Adams

Facing page: Dr Ted Heffernan in front of a monastery where he once conducted a medical aid program during Operation Hayman on Long Son Island in early November 1966. The area had not changed much in the intervening years and it brought great delight to the doctor to see where he had once worked with the local Vietnamese community. Photo courtesy Rupert White

The ubiquitous hawkers and peddlers will pursue tourists almost anywhere to sell their souvenirs and goods. Ambushed and with nowhere to go atop the monument to the Viet Cong in Vung Tau are, in the foreground and from left to right, Rupert White, Dr Tony White and Doffy White. In the background, considering the merits of yet another T-shirt they don’t need, are Fred Pfitzner and tour guide Garry Adams. Photo courtesy Paul Greenhalgh

Resplendent in their 5 RAR cravats and ready for a night out in Vung Tau are, from left to right, Ron Shambrook, Dr Tony White and Peter Isaacs. Photo courtesy Tony White

The ever busy Hoa Long markets are still a thriving meeting place for the local villagers who rely on fresh produce daily. The village was known to be pro-Viet Cong during the American War and supportive of anti-government activities. Photo courtesy Roger Wainwright

Peter (‘the Pirate’) Isaacs entertaining a horde of Catholic school children in the town of Binh Gia where the 5 RAR pilgrims stopped for a rest. The friendliness of the local populace is one aspect that never fails to impress visiting veterans. Photo courtesy Ron Shambrook

The opportunity to dine out in one of the many fine restaurants in Viet Nam was not passed up by the 5 RAR pilgrimage group when they had a sightseeing day and enjoyed lunch at the Ha Hoi Restaurant in Hanoi. Photo courtesy Roger Wainwright

The 5 RAR pilgrimage group pose on the steps of their hotel in Hanoi towards the end of their tour. Pictured standing from left to right are Dr Ted Heffernan, historian Elizabeth Stewart, tour guide Garry Adams, Roger Wainwright, Fred Pfitzner, Peter Isaacs (eye patch), John Taske, Tina Wainwright, Paul Greenhalgh (front), Ben Morris (beard), Joy Heffernan and Ron Shambrook. Seated are author Gary McKay and Wendy Greenhalgh. Photo courtesy Paul Greenhalgh

In 1966 the 5 RAR officers took a group photo at Back Beach, and when the pilgrimage group regathered there in 2005 they did not let the moment pass unrecorded. Recreating situations such as group photos (and the Nui Dat medical fraternity champagne toast) can provide lasting memories that allow the veteran to assess the passing of time and place their past service in perspective.

The pièce de résistance, however, was saved for when the group assembled for dinner one night in Vung Tau, dressed resplendently in slacks, shirts and gold battalion cravats. Did they look out of place in Vung Tau? Absolutely. Did they care? Absolutely not. The party then had a group dinner at a local restaurant owned by expatriate Australian Alan Davis and his Vietnamese wife Anh, during which Tony White showed a compilation video from all his 8-mm film that he took during his tour of duty in Viet Nam. It created a terrific atmosphere—and the bar owner’s wife, who came from near Binh Ba, recalled some of the incidents on the film footage and said it brought tears to her eyes when she recognised the Army doctors doing their Medcaps. It was a memorable evening all round.

Long Son Island

Not far north up the road from the port city of Vung Tau is Long Son Island. The island is about seven kilometres long from east to west, three kilometres wide from north to south, with a large hilly complex on the eastern end. During the war it was totally isolated, except by boat; today a causeway at the eastern end connects the island to the mainland. Near the causeway is a village, and a hamlet is located at the far western end. Apart from some industrial estate development near the causeway, the island has not changed very dramatically since 5 RAR conducted Operation Hayman between 8 and 12 November 1966, a search and clear operation designed to flush any lurking enemy out of the hilly, scrubby areas into the more open lowland areas where they could more easily be rounded up. During the operation, Australian SAS patrols stood by in inflatable boats to intercept enemy soldiers fleeing the sweep. The insertion was not without incident, as Ron Shambrook recalled:

We flew into the top of this hill and it was a marginal LZ because the gradient of this hill was very poor; too steep. And anyway the first four choppers landed and they indicated that they were getting some small arms fire. I came in in the second group of four, and so our attention to detail was good at that stage, because nothing rivets your attention more than a little bit of lead flying through the air, but there was none when we landed. Anyway the fourth lift came in and one of the pilots over-corrected and thrashed the plane to bits by running the rotors into the hill. I thought we were being mortared; it made an awful lot of noise and I didn’t know what was happening there for a moment.19

In 2005, the 5 RAR group returned to Long Son Island and after some good observation and deduction were able to determine which helicopter pad they had flown into halfway up the hillside—it was virtually unchanged. Having kept their operational maps, the veteran infantrymen were able to locate almost exactly where they had fought and where various incidents occurred. Ted Heffernan had conducted a Medcap in the local village on Long Son Island, and located a monastery close to where he had helped the villagers during the offensive operations being conducted about two kilometres away. Wandering around the small village, Ted was able to recognise buildings and the area where he had worked during Operation Hayman. When he returned to the group he was beaming from ear to ear and telling all and sundry what he had found. The tour bus filled with smiles.

The Horseshoe

The Horseshoe was an almost circular hill about eight kilometres south-east of Nui Dat—which was still within artillery range—and less than one kilometre north of a large village called Dat Do. It was a prominent feature that allowed observation over a large area of the flat countryside: with binoculars it was possible to see almost anything that moved to the east of Dat Do village, making it an excellent vantage point and information-gathering site.

A permanent fire support base was established on The Horseshoe, normally comprising a rifle company, a section or more of 81-mm mortars and three armoured personnel carriers (APCs), providing a ready reaction force to rapidly assist any troops in trouble or to set up quick roadblocks to intercept suspicious traffic. It was also well defended with Claymore mines, barbed wire and fighting bays dug into the rocky soil.

The Horseshoe was established in 1967 by a rifle company from 5 RAR and commanded by Paul Greenhalgh, whose previous company had been positioned on top of Nui Dat hill. Paul was a rare breed—an unmarried major—but had become engaged to future wife Wendy, who was a school teacher working at RMC Duntroon teaching dependants’ kids. He didn’t especially relish being sent to establish the fire support base at The Horseshoe—and it wasn’t always known by that name, as Paul explained:

Well actually the Horseshoe feature wasn’t given a name when we were sent out there. It was just a volcanic crater—but I will say it now, being a student of military history, General Christian de Castries had named all of his outposts [at Dien Bien Phu] after his mistresses. I called it Fort Wendy.20

But digging into the hard granite rock was not easy and before long expletives were being directed at the name of the outpost. Paul decided that he wouldn’t have his fiancée’s name slurred anymore and so it became known as The Horseshoe. In 2005, the woman after whom this rocky outcrop had once been named stood next to the feature and remarked modestly about how she felt upon finally seeing it:

I’m glad actually it [the name] only lasted two days. It would have been quite weird to have a place in Viet Nam named after you . . . It was great that Paul had it for two days, but it was much better that it went on to be called The Horseshoe.21

Fred Pfitzner, who bounced from one company to another filling in shortfalls as a company second-in-command (2IC)—at one stage he was in Charlie Company for only 24 hours before being reassigned—took up the story of The Horseshoe:

I became known as ‘Fred the Wandering Jew’. I didn’t know where they were going to send me and the next thing they said was, ‘Well we are building The Horseshoe, the 2IC has gone off home on the advance party and you are it.’ So I went and did that with Paul Greenhalgh and we built The Horseshoe. That was good; I enjoyed my time in Delta Company.22

On my last four trips, including the 2005 5 RAR pilgrimage, I have been unable to gain access to The Horseshoe owing to blasting at what is now a quarry site. The northern half of the feature has been dug out, and if quarrying continues at the present rate, within five years the hill will most probably be unrecognisable to veterans.

An Nhut

For the 5 RAR group one of the principal reasons for coming on the pilgrimage was to return to the scene of a dreadful mine incident that occurred during Operation Beaumauris between 12 and 14 February 1967. A cordon and search was being conducted of the hamlet of An Nhut, which is ten kilometres east of Ba Ria. Charlie Company had its headquarters decimated when the OC, Major Don Bourne, the company 2IC Captain Bob Milligan and the artillery forward observer Captain Peter Williams were all killed. Six other soldiers were wounded by the blast. The battalion had only nine weeks to go before they returned to Australia.

The village of An Nhut has only grown a little since the war, and the rice-paddy area where the mine incident occurred is still basically as it was 40 years ago. Roger Wainwright had a photograph that was taken just before the explosion, and when his group went to the site in 2005 they were able to stand within five metres of where those men were killed. In a moving tribute, Roger laid a floral offering at the spot. Under a cloudless sky in searing heat everyone observed a few minutes’ silence to remember those who lost their lives or were wounded on that terrible day.

Roger was a platoon commander in the ill-fated Charlie Company. Determined to get to An Nhut, he had ensured that the tour company could and would take his group there during their pilgrimage. He explained why it was so important to him and the others:

It was a significant moment in our company as well as the battalion. To lose three people like that—and let’s not forget the six wounded, of which a couple had to come home. I got to know the family, the widow of Don Bourne and his four children. I’d phoned them just about a month ago [September 2005] and spoke to one of the sons and said I was coming over here, and asked would you like us to lay something on the spot if we could find it. And they said to me, ‘If you can just take a photograph of the position.’ We achieved that. And apart from the rice paddies being green as against dry and brown at the time, it’s exactly the same shot.23

There are moments during pilgrimages when incidents like An Nhut will sweep over veterans and create a melancholy. It cannot be avoided, nor should it be. John Taske was a good friend of Charlie Company’s 2IC Bob Milligan, and sadly recalled:

I went over to his tent [the night before] and he was telling me all about how he’d finally made up his mind—coming up on the ship he’d kept talking about this girl and whether he should get married and stuff like that. And then he’d told me that he was getting engaged and he was just so full of joy at going home. And then, to hear a couple of days later that he’d bought it, was pretty sad.24

The Long Hai Hills

The Long Hai Hills are a cluster of relatively high hills in the south-eastern corner of Ba Ria–Vung Tau Province, sitting about twenty kilometres to the south of the 1 ATF base at Nui Dat and running down to the coast. During the war, with its thick vegetation and steep slopes strewn with granite boulders, it was a formidable piece of terrain that was easy to defend and very difficult to attack. It was an ideal sanctuary as the approaches were open and flat, and any encroaching movement could be easily detected, especially in the dry season. The massive boulders and natural caves and crevices afforded excellent concealment and protection from direct and indirect fire.

The Long Hai Hills were never a good place to get to, as Paul Greenhalgh recalled: ‘You were always buggered! You were looking at your toes as you were climbing hills. Fatigue when we got up to the top . . . It was extremely wearying and tiresome.’25

The Long Hai Hills were also known as the Minh Dam Secret Zone, after a Viet Minh base there named after the local guerrilla leader, Minh, and his deputy, Dam. The Secret Zone had been a guerrilla stronghold since the First Indochina War and remained active against ARVN and Australian troops during the entire Viet Nam War. It was never conquered and was considered a notorious ‘badland’ as it was difficult to manoeuvre, and mines and booby traps were prolific. Whenever enemy troops needed a place to rest, refit or recover they would use the Minh Dam Secret Zone as their sanctuary.

Derrill De Heer had to work down in the ‘badlands’ on occasion and sometimes flew over them when he was working the Psyops Unit. When asked what made him apprehensive he responded emphatically, ‘Flying over the Long Hai broadcasting or dropping leaflets from a low height. I was shot at a number of times. The aircraft was not allowed to retaliate as we wanted them to surrender.’26

Peter Isaacs didn’t relish working in the area either, adding: ‘The Long Hai Hills had bad memories for us at the end of our tour.’27 As they did for rifleman Bill Kromwyk: ‘6 RAR took a lot of casualties there actually. Yes that always worried me, I used to hate being in that area.’28

Fred Pfitzner was intrigued by his visit to the Long Hais in 2005:

Getting up into that area I found quite fascinating because every time we’d try to get up there we got bloodied. No matter whether it was a unit like 5 RAR on its first tour, or 4 RAR on its last. If you went up there you were going to get clobbered. So when you get up into it you can see what a fiendishly difficult area it would have been to get into and maintain any sort of presence.29

Most tour groups visiting the province are offered the option of going up into the Long Hai Hills. A lookout right on the eastern tip of the range offers spectacular views up and down the coast, and near the lookout is a small monastery that is home to Cao Dai monks. There is also a small museum and cafe run by an ex-D 445 Battalion lieutenant, Hoang Ngan, which has been operating for approximately eight years.

The area has allegedly been cleared of mines and booby traps, but one should nevertheless exercise caution and avoid moving off the well-defined tracks. The Long Hais had ordnance of all kinds dumped on it during both Indochina wars, and there are undoubtedly still many undiscovered and unexploded munitions in the hills. When the natural gas pipeline was being laid through supposedly cleared areas several years ago, in excess of 100 unexploded ordnance items were reportedly found.

I have visited the area on three occasions and each time former Lieutenant Hoang welcomed me as a comrade in arms. It can be disconcerting at first to stand in front of a former foe and shake his hand knowing that at one stage you were both possibly trying to kill each other. However, the warmth and hospitality shown by former enemy soldiers is not uncommon, and Australian soldiers are met with open arms and with disarming frankness.

The 5 RAR pilgrimage group had not encountered a former Viet Cong soldier before, and afterwards were individually asked how they felt about meeting Mr Hoang. Ben Morris replied simply, ‘That’s the time the hating stopped. Just meeting him; he’s a human being . . . He welcomed us.’ Of the hundreds of Viet Nam veterans that I’ve spoken to over the last three decades, very few hold or feel any ‘hatred’ towards their former foe. Fred Pfitzner put it thus:

They were doing what they had to do, and we were doing what we had to do. I mean, there’s a universal brotherhood of infantry. You all suffer the same way. And how they got in there [to the Long Hais] with large bodies of troops and managed to secure them away from observation, the air strikes, and artillery. How they managed to feed and water them. How they managed to fix them up medically when they needed it. I’ve got nothing but admiration for them. And even at the time, I thought, you know, these blokes are no dills. They know what they’re doing.30

Roger Wainwright was similarly philosophical. ‘I think we’ve got to respect what our foes were doing at the time,’ he remarked. After reflecting that both he and Mr Hoang had been of the same rank, he added: I think the fact is that war overall is a nasty thing, and the suffering occurs to both sides. And to meet them in more friendly circumstances all those years later is interesting. And, you can’t say there is any malice remaining in this day and age. It was great to meet him. I would have liked to have had a longer chat with him.31

As a doctor, Tony White didn’t physically go up into the Long Hais during the war, but certainly had to deal with the result of Allied operations in the foothills. ‘My main link with the area was the Operation Renmark mine incident, and of course we couldn’t get within cooee of that.’32 Operation Renmark was conducted in the Long Hai Hills between 18 and 22 February 1967, and 22 February was another black day for the 5th Battalion. Three infantry soldiers and two cavalry crewmen were killed, and another nine men were wounded, when their armoured personnel carrier ran over a mine most probably constructed from a large unexploded aerial bomb. Four Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant John Carruthers, was leading a mounted advance and had struck the mine.

During the immediate commotion and commencement of the casualty evacuation phase and reorganisation of the company, an M-16 ‘Jumping Jack’ mine was triggered—and within four minutes of the initial incident many more men were seriously wounded. Captain Tony White was the RMO of 5 RAR and was flown in by Sioux helicopter, to be greeted with an atmosphere of deep shock and fear. Captain Peter Isaacs notified Task Force Headquarters and within minutes an Iroquois Dustoff chopper was overhead, awaiting the preparation of a landing zone at the point of the explosions. The scene was horrendous, with a total of 31 wounded.

Another excruciating problem for Tony was determining who would be treated first of the large group of casualties, several of whom were in danger of imminent death. Fortunately the 36th US Evacuation Hospital at Vung Tau was only five minutes away by Iroquois, and the more severely wounded cases were on operating tables within 25 minutes of being wounded. Major Bruce McQualter was still just conscious when Tony arrived, and urged him to treat the 4 Platoon casualties first. Shortly afterwards Bruce lost consciousness. Lieutenant Carruthers was also seriously wounded, and despite severe head and body injuries, each man held on to life with great tenacity. Lieutenant Carruthers died on 24 February, and Major McQualter at 5 a.m. on 5 March.33

Even after having to deal with the incredible trauma and horrific injuries inflicted by the former enemy, Tony White expressed these feelings after meeting Mr Hoang:

No ill feelings at all. No, I feel that was then. He was a 17-year-old who went in there and he was defending his country. We were on our side doing our duty, and it just highlighted the absurdity of the whole exercise. And many deaths and a lot of people knocked around mentally and physically.34

Binh Ba

Binh Ba, seven kilometres north of Nui Dat, was—and still is today—a rubber plantation workers’ village and very picturesque. The houses are built in orderly rows, and most have concrete walls, tiled roofs, and wooden doors and window shutters. While there are trees and shrubs between and at the rear of houses, the front is usually well mown. It has a properly laid out road system, and the eastern edge of the village is next to the former Route 2 roadway.

This village was cordoned and searched by 5 RAR very early in their tour of duty, and many following battalions based their modus operandi on how 5 RAR went about their business. Roger Wainwright recalled that first cordon of the village and what he remembered most:

I suppose the approach to it by night into the position as we did with all of those cordons. It was pretty much the very first one that we did, and of the absolute vital necessity of linking up at night time with other companies so that you don’t have clashes with other platoons. And walking at night with toggle ropes.35

Today the village has grown somewhat, but is still essentially a community of local rubber plantation workers. Entry is restricted at times—on my last two visits I have been denied access to the village, but I have not been able to ascertain exactly why. The day the 5 RAR group arrived, entry was again restricted and it was bucketing rain. The group was not given a permit to enter the area from the Vietnamese government. Battle sites are declared ‘sensitive areas’ and permits must be obtained through the government tourist agencies or arrest and detention can result. People were allowed off the bus and looked across at the village. The veterans peered through the pelting tropical downpour at where they had once formed a perimeter around the village and flushed out dozens of Viet Cong soldiers and sympathisers. Adjutant and assistant operations officer Peter Isaacs commented ruefully, ‘Binh Ba was unrecognisable apart from the water tower, and the airstrip is invisible from the road. There was no sign of the Regional Forces post we constructed.’36

Roger Wainwright was also disappointed he couldn’t get into the village in 2005 because, ‘After we did the initial cordon and search of Binh Ba, our company lived there for almost two months, and that is probably why we never finished digging in at Nui Dat.’37

Aviator Peter Rogers was also interested in visiting the village because he had been involved in the Battle at Binh Ba as part of Operation Hammer from 6 to 8 June 1969. ‘It was a colossal stoush while I was there,’ he reflected.38 The road heading north up from the old Task Force base at Nui Dat was once an arterial road between isolated villages, right up to the next province capital of Bien Hoa. But since the war, the growth of the populated areas has been staggering. As Peter observed, ‘I couldn’t recognise the place. It is all ribbon development now.’ Peter was saddened that he couldn’t identify where the former airstrip had been located, north-west of Binh Ba, because two aviator friends were shot down and killed near there just after he finished his tour of duty.39

The tour group travelled from Binh Ba west across the area that was formerly known to Australians as the Hat Dich region. During the war it was a large tract of primary and secondary jungle; now a highway runs through it, supporting ribbon development, small towns, coffee and pepper plantations and market gardens. Fred Pfitzner said he couldn’t believe it: ‘I was gobsmacked at the development—it is bloody good to see it.’40

Xuyen Moc

Twenty kilometres due east of the Nui Dat base, but some 35 kilometres by gravel road, was the town of Xuyen Moc (pronounced ‘Swen Mok’). It was a settlement that swelled from a rapid influx of Catholics who left North Viet Nam once the country had been divided in 1954.41

During the American War, the isolated town was subjected to constant harassment by the Viet Cong, who felt secure in attacking the local populace given the long reaction time required to deploy a large combat force to restore order and repel their forays. The road leading out to the town via the provincial capital of Ba Ria and the district capital of Long Dien was often mined, and subject to frequent motor vehicle ambushes. In 1966, 5 RAR was given the task of clearing the road and establishing a presence in Xuyen Moc. As Fred Pfitzner observed on the logistics of even getting there, ‘To actually have got out to Xuyen Moc required a special operation every time it was ever done.’42 After the war, the resettled North Vietnamese Catholics paid the price for not buckling to Viet Cong pressure: the town was the very last in the province to receive electricity.

Dr Ted Heffernan conducted Medcaps at Xuyen Moc, and when he returned in 2005 he was absolutely thrilled to see the town and the people again. When the group alighted from their bus near a large Catholic school at Binh Gia they were mobbed by young children in bright blue school uniforms. Chaos reigned as the school kids gathered around, and some were rather bemused when staring at the heavily scarred, one-legged and black-eye-patched Peter Isaacs, who replied rather earnestly to an enquiry from an inquisitive child that he was in fact a pirate. Show and tell would have been something to eavesdrop on the next day.

Wendy Greenhalgh participated in a romp with several tour members and dozens of school kids and said later, ‘Everybody was so happy—and I thought, God, why couldn’t it always have been like that?’43