The first thing Blumfield said after my apology was that he wanted me to take the MMPI test again and actually answer the questions. All of them.

I told him that I’d be happy to do so after they reduced the medication I was on.

No, Blumfield insisted. Test first, then he’d talk with Dr. Chang.

Once again, the test felt like a daylong trip to the dentist. It was awful, and I let everyone know how miserable I was while taking it. I really wanted to tear it to shreds and stuff it down the toilet. But I didn’t. I made myself keep going.

The next afternoon Blumfield and I were in the midst of our regular afternoon session when he got a page to the nurses’ station. He put my file down on his desk and excused himself.

Lying on top of the open file was a neatly typed “Report of Consultation,” dated after my second blowup in his office.

I turned it around and began reading.

Two decades later I’d walk back into Timken Mercy, take the elevator to the records room in the basement, and open up the file containing all my paperwork, nurses’ logs, and reports from my stay at Timken Mercy. I was surprised that they still existed, having been retrieved from a warehouse a few weeks after I’d requested to see them. The file jacket said that I had also requested to see these records three years after being released from the hospital, but I have no memory of doing so, or why.

Once the file was open, the first thing I noticed was the “Report of Consultation.” Seeing its slightly yellow pages took me back to a vivid memory of sneaking a peek at it that afternoon in Blumfield’s office, absorbing every word as quickly as I could.

INTERVIEW AND BEHAVIOR: This patient presented a bespectacled and tall male, of average build, with clear skin and an odd haircut that is similar to that worn by some subcultural “punk” musicians and their followers.… Anger was not expressed in a healthy, direct way. The patient is very combative.… Much conflict between family and acquaintances over his odd behavior and atypical life style.

Dynamically, this patient has a veneer of socialization that is constructed upon a morass of confused emotions and instinctual drives. He subconsciously realizes this; that his emotional underpinnings are tumultuous and very tenuously balanced within himself. He also feels that he has been irreparably damaged and the pain from this, when at a conscious level, becomes unbearably painful. Although his thinking is yet essentially intact, it too is starting to show signs of deterioration. For example, there is a clear paranoid tendency beginning to develop.

When Blumfield walked back into his office and noticed that I was reading the report, he made no effort to stop me.

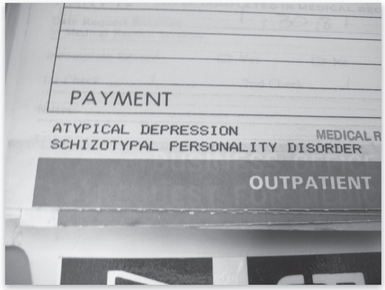

At the bottom was his diagnosis: schizotypal personality disorder. I pointed to it and looked at him, as if asking what it meant. Blumfield opened a book on his desk, spun it around, and moved it toward me.

Schizotypal personality disorder: “a pervasive pattern of social and interpersonal deficits marked by acute discomfort with, and reduced capacity for, close relationships as well as by cognitive or perceptual distortions and eccentricities of behavior, beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts.”

It went on to describe a bunch of symptoms and indicators: odd behavior or appearance, poor rapport with others, a tendency to social withdrawal, odd beliefs or magical thinking, suspiciousness or paranoid ideas, and about a dozen others. Some didn’t fit, most did. As I read through the entry, I couldn’t decide what idea was worse: that someone thought of me this way or that it might be true.

“Do you have any questions?” Blumfield asked.

“So, this is based on your opinion?”

“My assessment, yes,” he said. “Plus the tests you’ve taken.”

I remember wondering to myself why he would let me read it. Was it to humble me? Test me? Teach me something? Whatever he was trying to accomplish, it probably worked. After what felt like an hour of processing this in my head, I finally spoke up.

“So where does that leave me?”

“What do you mean?” Blumfield said.

“Where do I end up?”

“There are a few different directions,” he said. “Some continue into schizophrenia; others find that they can manage quite well with medication and therapy.”

“How do I know where I’m heading?” I said.

“Well, I think a lot of that depends on your treatment—and you have some hand in how that evolves,” he said. “Many people who aggressively deal with this live very normal, happy lives.”

“I was watching TV once and there was a report on about a guy who had his nuts blown off in Vietnam,” I said. “I mean, they didn’t say ‘nuts’ on TV or anything, but it was pretty obvious what they were implying.”

“Okay,” Blumfield said. “I’m not sure I’m following you.”

“Well, he lived in a wheelchair and had no balls,” I said. “I mean, he adopted a kid and was married to this woman with big tits and huge hair, but there was a pall over everything: that he couldn’t walk and had no balls.”

“What is your point?” he asked.

“I guess that all depends on what you define as a ‘normal’ and ‘happy’ life, huh? I mean, this guy had all this stuff that was supposed to make him happy, but you could tell that all he really wanted was his balls back.”

Blumfield just smiled, then lowered his head to write some notes, probably something like “Has trouble expressing abstract concepts and ideas.” In truth, I had no idea what “happy” and “normal” were, and I doubted I’d recognize either if I found it, let alone be able to express it. And I was positive that whatever would constitute “happy” and “normal” in my life would make no sense to anyone else.

I could hear some guitar chords reverberate from down the hall in the dayroom.

It was Jesus H. Christ singing David Bowie’s “Young Americans.”

For thirty minutes every day Jesus H. Christ was allowed to play his guitar. He wasn’t allowed to keep it in his room or play unsupervised. But for a half hour a day, the nurses would let him set up in front of their station and play. Jesus H. Christ knew a lot of songs.

“Would you mind terribly if we picked this up later?” I asked Blumfield.

“Tell me where you’re at. What are you feeling right now?” he asked me.

Over the several days he’d been allowed to do it, Jesus H. Christ’s thirty-minute strumming had slowly evolved into unsanctioned sing-alongs. I loved the sing-alongs. There is something about singing in a group that brings you a kind of peace and release that little else can equal.

Stan was also surprisingly well versed in song lyrics. Silas would stand in front of everyone, pretending to conduct the 5B chorus. The sing-alongs were probably the most joyful parts of every day. Patients who hadn’t responded to or acknowledged anything since they arrived would suddenly perk up and sing along with “Folsom Prison Blues” or “Let It Be.” Nothing brings people together like the shared love of a song. Our sing-alongs were made even sweeter because we knew that anything we enjoyed doing this much would eventually, and irrepealably, become forbidden. Some doctor or nurse would come up with a reason that singing together would cause a disturbance and suggest some other activity, like checkers or watching TV, and that would be the end of it.

“I guess right now I’m feeling a lot of things,” I said. “But I guess more than anything I feel like I want to go sing with Jesus H. Christ.”

Blumfield put down his pen and extended his arm toward the hallway.

I was already singing as I ran toward the dayroom.

My therapy sessions continued almost every day, as well as my occupational therapy, moderated study group, and group therapy. In each, I basically learned to tell the counselors and therapists what they wanted to hear. It wasn’t like I was lying to them, but I simply learned to convey things in the way they could understand, almost like speaking in another language.

The only time I really expressed myself was during Laura’s visits. She came every day or two, and we just sat in a corner by ourselves. By this time, our conversations were less about gossip from the ward and more about untwisting the mess of knots I’d tied through my life. Laura rarely gave advice. Instead, she’d just ask questions about the way I felt and constantly probe by asking me to explain what I meant in deeper detail. She really, never once, pushed or suggested I do anything, but she would quietly nod with approval when she heard things she liked. I learned to live for those nods.

After ten days in 5B, I was moved to 4B. For the most part, I behaved myself, with the notable exception of secretly forcing myself to throw up all my medications. One morning I had woken up to an orderly who wanted me to swallow nine pills—plus a stool softener. Fuck it, I said. No way.

This led to a mini-conference with the nursing staff, then a hallway consult with Dr. Chang, then everyone marching into my room to tell me that I needed to take these pills. If I did not, there would be serious ramifications for my Progress Plan.

Fine.

I took the pills just as I was told.

Then, a few minutes later, I walked into the bathroom, stuck my finger down my throat, and threw them all up again. I repeated this for three days.

Of course, eventually I was discovered; Dr. Chang ordered that I had to take all my medications in the presence of a staff member, then sit by the nurses’ station for thirty minutes. Basically, now even my digestion was a supervised activity.

Sitting by the nurses’ station kind of felt like wearing a dunce cap in the corner of the classroom. All the 4B residents wanted to know what I’d done and why I was sitting there. After a while, I started to notice how that chair was kind of a perfect vantage point. Jesus H. Christ’s new medication had made him calm and no longer interested in screaming and running around naked at night. Therefore, he, too, had made his way downstairs and was now happy escorting his very pregnant girlfriend and his parents around 4B, showing off all the wonderful new features like doors on the bathrooms and leather stamping tools in the occupational therapy room (excellent for customizing the wallets and belts we were instructed to make). There was a blond guy who looked like a roadie for Lynyrd Skynyrd, who’d sit in front of a window rubbing his lower lip for at least three hours. A woman in the corner of the dayroom would start to look very upset, get up and sit in a different chair, and seem fine for another few minutes until she got distressed and moved again. Some dude was playing with himself while watching The Price Is Right. Stan was flirting with a woman who’d been brought in a few days earlier. To be honest, the residents of 4B weren’t that much better off than the residents of 5B—in fact many of them had been on 5B when I arrived—but 4B had a more relaxed vibe, a feeling that things were a bit more under control, less frantic, panicked, and harsh, as well as mildly less depressing.

I kept wondering to myself what these people’s lives would hold. They, like me, were just a few days from getting tossed back into the world. What would happen to them? How would they cope? How long would it be before one of them was back here? Or somewhere worse?

One day, as I digested my meds, I saw a girl named Sarah smiling at me from across the dayroom. She was sitting at a table with a tray in front of her. The natives of 4B had gone into quite a flutter when she arrived. The waves of people, specifically men, who paraded over to wherever she was dwindled a tiny bit when word spread that she was seventeen. Simply because she was the subject of so much ward gossip, I’d pretty much avoided her. It seemed that the only people more gossiped about than Sarah were the men who went over to talk to her.

I looked away for a moment, then looked back. She was still looking at me and smiling.

What the hell, I thought.

As I approached I could see that food on the tray in front of her was barely touched. Her arms were spread out away from her and lying on the table, making the mounds of gauze and pads wrapping her wrists even harder to ignore. She seemed like she was in pain whenever she tried to move them.

“What’s the matter?” I asked. “Is the chicken casserole so delicious it’s blowing your mind?”

She laughed. “No, it’s still just kinda slow going with this,” she said, rolling her palms up. I could see some seepage coming through the bandages. “I asked the orderly to help me, but I guess he got busy. They keep fucking with my meds.”

“Amen to that,” I said, sitting down next to her and picking up her spoon.

I scooped up a small bite on the spoon, brought it up to her mouth, then slowly swung it over to mine. Just before it reached my mouth, I gave her a look of faux shock.

“Oh, did you want this?” I asked.

She laughed again.

I brought the spoon up to her mouth. She backed away slightly and looked into my eyes, then slowly opened her mouth and took in the bite. We just sat there silently for a few minutes. Me scooping up spoonfuls and feeding them to her. Her smiling between bites.

“Hey! Hey!” we heard some staff person yell from the nurses’ station. “What are you doing? You aren’t permitted to feed another patient!! Stop that right now! Stop!”

“In about thirty seconds they are going to force this spoon out of my hands,” I said softly, continuing to serve her while I spoke. “And if they forget to feed you at breakfast, I’ll be back.”

“Put that down!”

As I expected, an orderly grabbed my hand and took the spoon, while a nurse quickly looked over Sarah.

There was some yelling back and forth, and the scene ended with me walking back to my room before they had a chance to order me there. I didn’t act out or throw a fit. It was the first time in years I’d made an effort toward anything that wasn’t meant to fuck things up. It was the first time in years that I’d stood up for someone other than myself.

“Well … you ready to go?” Laura asked.

I thought for a moment.

“No,” I said. “I doubt it.”

Both of us sat there, looking toward the door, neither of us sure what we were supposed to do next.

If there is one thing I’d learned about hospitals, it’s that they aren’t interested in healing you. They are interested in stabilizing you, and then everyone is supposed to move on. They go to stabilize some more people, and you go off to do whatever you do. Healing, if it happens at all, is done on your own, long after the hospital has submitted your final insurance paperwork.

While I was in Timken Mercy, I often expected that when I was discharged I would walk out to a bright sunny day and simply skip off into my newly retooled and absolutely perfect life. The reality was far different. After twenty-two days of almost constant confinement in the mental ward, I was what could loosely be defined as “stable,” but that’s about it.

I’d been allowed outside the ward on two occasions. Once, I was given a one-hour pass to walk around in the hospital’s garden with my mother. The second trip was a six-hour “day visit” back to my parents’ house. My brother was away from the house all day, and my father barely spoke to me. Basically I spent the entire visit listening to my records and walking around the backyard alone.

Dr. Chang had decided to try out a new drug mixture for the day of my visit home, which had left me barely able to stand. He’d finally cut back on the number of pills he was prescribing. I was now down to three pills, three times a day. But they must have been horse tranquilizers or something, as within an hour of taking them, I could barely spell my name.

In hindsight, I can see that numbing me up before sending me back into my real world might not have been all that bad an idea. Before going into the hospital, I’d managed to turn my life into a huge shell game. It wasn’t until I went into the hospital that my family really figured out the extent of what was going on. For example, no one was aware that in the few weeks before I was admitted to the hospital, I’d written all over all the posters and artwork I had hanging on my bedroom walls. After covering them with ramblings, I’d slashed them to shreds yet left them hanging. I’d also scorched a ventriloquist doll and then hung the charred remains from the ceiling light fixture with an improvised noose. Those surprised by these discoveries initially included me, as I had, at first, no recollection of doing any of these things. Though once I was reminded of them, I knew I had done them. It is one of the strangest memory experiences I’ve ever had, then or since, almost as if my mind has erased any detail of these acts yet somehow managed to hang on to the utter certainty that they were my own.

My parents had decided to move me out of the attic into a room across the hall from their bedroom. I was pretty livid when my mother told me, but even I realized I was lucky to have a place to go to after leaving the hospital. T.J. Maxx was going to let me have my job back, which I equally didn’t deserve but was grateful for. It wasn’t really an act of compassion on their part—they were probably just happy to have someone to do the cleanup work.

At the ward there really was no big goodbye. With the exception of Jesus H. Christ, most of my original 5B brethren had already gone, tossed back into the chaos of the lives they’d left. No exchanged addresses or phone numbers. Our time together was simply over. The only person I ever saw again was Silas, when I went down to the courthouse to pay a parking ticket a few weeks later. Despite our having been roommates for most of our time at Timken Mercy, Silas pretended he didn’t remember who I was.

I was set up to see both Blumfield and Dr. Chang again within a week, so they didn’t feel the need for a goodbye either. The nurse simply told me that I was free to go home whenever I chose. Since both my parents were at work, I asked Laura to borrow a car and come pick me up.

We were sitting on my bed talking when she suddenly looked at me.

“Wait, do we even need to be here?”

“I don’t know, I guess not,” I said.

When we stepped outside, the sun was bright, blindingly bright. It would disguise what lay in front of me. Broken relationships that would take years to heal. Questions I wasn’t ready to answer. The previous twenty-two days hadn’t really solved anything. All my problems and issues were still out there, waiting patiently for me. The only real question was whether I was now any better prepared to deal with them.

As we got up and started toward the door, one of the nurses ran up to me.

“I almost missed you,” she said. “You got a package this morning. We didn’t want you to leave without it.”

The package had been opened and checked for contraband, like all incoming packages were. I reached inside the open envelope and fished out a piece of paper.

“Hear you are getting out,” it said. “Thought we’d send you a little something to celebrate.” It was signed by Phil and Ben. I reached inside the envelope to pull out the present they’d sent me.

It was a single-serving box of Cap’n Crunch.

She came back on my first night home from the hospital. I saw a flash of Her in a dream. As soon as I saw Her, I was awake, and stayed that way for the rest of the night, upright in my bed in my new bedroom, shivering, staring into the dark stillness, waiting to hear another noise or for the door from the attic to open.

I don’t think I ever really expected that She’d stay away forever, but the Little Girl dreams I began to have seemed different. Sometimes I was blind, my head was covered, or my eyes could not open, and the scenes of the Little Girl dream would play out around me, though I couldn’t see them. The new abbreviated ones terrified me just as much as every other Little Girl dream I’d had. As long as She remained upstairs, I figured I could deal with it—just hold on and bear it. If She started showing up in other places again, I had no idea what I’d do. That would definitely be a big problem.

The deal my parents offered was pretty simple. I could stay at their house until we determined what was best long-term. During that time, I could borrow my mom’s car to go to work and a limited number of activities. I had to sign my paycheck over to my parents, who would, in turn, give me an allowance. Even if I wasn’t using the car, I had to let my parents know where I was going when I left the house and when I’d be back. I also needed to keep myself out of any flavor of trouble.

For some reason, which I was thankful for yet didn’t understand, my parents were open to planning a move up to Kent State’s main campus in the fall so I could take another stab at classes. I’d start out on academic probation, but by some miracle or legal requirement, Kent agreed to give me another chance. Given what I’d been through, it was a risky move, but I think everyone, including my parents, realized that if I stayed in Canton, I’d just end up in the same cycle. I needed a change of scenery, a chance to be around different people. Plus, when I moved up to Kent, I’d be out of their house. Though they would never have said this out loud, I imagine that they were happy to see me be somewhere else for a while. Most of all, the idea of moving to Kent was a goal, something to aspire to and work for. In a life still filled with smoldering embers from my efforts to torch it, I was happy to have anything to look forward to.

“Dude, they told us you had bronchitis, but I knew it was bullshit,” Todd said, trying to make conversation as I swept up in the Housewares Department Saturday night. “Nobody goes into the hospital with bronchitis for weeks and comes out alive, man. I figured you got busted and went to jail.”

I told Todd there really wasn’t a whole lot of difference between the hospital and jail.

“So, did you nail some crazy bitches while you were in there?” he asked.

I just shook my head.

Todd kept following me as I brushed the dust balls toward the stockroom doors.

“Oh, and by the way, if you need anything to help you reacclimate to society, just let me know, I can set you up,” he said.

I told him no thank you, I had plenty of drugs at home that I was trying hard to avoid taking as it was.

“If you ever want to unload any of that stuff, that works, too,” he said.

After Todd went back to the Housewares Department, I saw Annette standing by the women’s fitting room. She leaned to her left and said, “Okay. What’s the password?”

She leaned to the right. “You got it.”

To the left. “Got what?”

To the right. “The password.”

I think this new Purple Rain dialogue was her attempt to cheer me up. Though I’d been back at work for a week or so, it was the first time we’d been scheduled together. While I was given a job, I was back in Receiving—sweeping, mopping, and taking out trash. Despite assurances from the managers that my “medical situation” had been kept in confidence, it was quite clear that word of where I’d been and why had spread throughout the store. I’m pretty sure it was the managers themselves who did the gossiping, as no one else would have had any idea where I was. Now even some of the regular shoplifters seemed to have gotten word.

I really wasn’t concerned with who knew what, but watching everyone try to cheer me up all the time quickly got old. I mean, what else would you do for a depressed and suicidal drug-abusing co-worker but bring a smile to his face by reenacting a scene from Purple Rain that wasn’t all that funny to begin with?

Annette leaned to the right. “The password is what?”

“Exactly,” she answered herself, forgetting to lean in the other direction.

“The password is exactly?” she said, realizing her mistake, and then leaning to the left briefly, before leaning to the right.

She burst out in laughter when she finished. I applauded for her.

“That was great,” I said. “What did you do, write down all the parts during the movie?”

“Yeah, I took shorthand,” she said sheepishly, instantly realizing that it sounded a bit weird.

“Well, good for you,” I said. “That was very nice.”

Nice. I was trying to be nice. In a strange moment of synergy, both Laura and Blumfield had given me the exact same advice, on the same day, about dealing with people.

“Okay, so you say that when you talk with people, you assume that they judge you or don’t like you or have other negative impressions of you,” Blumfield summarized.

“That’s correct,” I said.

His real-world office was filled with even more crap—piles of books, files, stuffed bookshelves, and yellowing photographs. Why would one person need all this, I wondered, let alone be able to find it or use it when he needed it?

“When someone comes up to talk to you, they not only want to express an idea or feeling, they want to express it to you,” Blumfield said. “That means that you have value to them. They are interested in having you hear their thoughts, and they value your opinion. I think that’s implicit in the gesture.”

“The other day when I was sweeping up in the Men’s Department a woman kept staring at me,” I said. “I asked her if I could help her with anything, and she told me that she prayed for my soul.”

“Did you ask her why she wanted to pray for you?”

“No, I didn’t have to,” I said. “She told me I was going to hell.”

“Why did she feel you were going to hell?”

“Because I was wearing earrings.”

“Earrings?” Blumfield repeated.

“Yeah, so I asked her about this,” I said. “She just looked me up and down and said, ‘Yes, those faggot earrings.’ ”

“I’m not sure what that story means to our conversation,” he said.

“I don’t think she was very interested in my opinions,” I said. “I don’t think she felt I had value, implicit or otherwise.”

“Eric, you probably interacted with a hundred different people that day,” he said. “And you are allowing your experiences with one to determine how you react to everyone. Doesn’t that strike you as unfair to the dozens of other people who do think you have value and find pleasure in sharing their thoughts and experiences with you? I think you’ll find that when you stop assuming a defensive position that you’ll be pleasantly surprised by what you find.

“You are such a compassionate and curious person by nature, Eric. You spend a lot of time and energy fighting against it, trying not to be compassionate. Just be with them, acknowledge their interest in you, and let your natural curiosities go.”

Laura’s fourteen-word version of the same speech, delivered while sharing a Frosty in a Wendy’s parking lot later that night: “Just don’t be a dick. Listen to people and realize they are trying, too.”

Despite thousands of dollars spent on counseling and medication and hospitals and tests, the best therapy I received happened late at night, in parking lots, cheap restaurants, and driving around town with Laura.

Just don’t be a dick.

I don’t think there was ever a time that the staff of Timken Mercy was convinced that I could live without doing drugs. They really didn’t know what advice to give me. One counselor suggested that I attend NA meetings after I left, if for no other reason than to learn from other people’s experiences. (I never went.) Another stressed that I needed to avoid any narcotic, powerful stimulant, or mind-altering substance for life, or I’d just end up back in the hospital again. But it was actually Blumfield who, kind of off the cuff, came up with the solution that I’ve tried to live by ever since. He suggested that if I could enjoy something without it making me high, fine. If it was impossible to enjoy something without becoming inebriated, then avoid it. In other words, it is pretty difficult to “enjoy” pot or pills without feeling something. But a beer or two beers? Shouldn’t be a problem, he suggested; don’t think of it as a problem. But I was still scared to test myself. My challenge was just keeping it to those two beers. No one other than myself had any faith that I could actually pull it off. Except Laura.

She decided that we should put Blumfield’s theory to the test on one of the first nights I was allowed out. We went to the College Bowl, just a few blocks away from my parents’ house, and ordered a draft.

The bartender sat it down in front of me. It was golden and cold and looked perfect. We stared at it for a few moments. It was the first alcohol I’d seen in over a month.

“Should I drink it?” I asked Laura.

“Sure, why not. What’s the worst that can happen, right?”

I picked up the draft and downed the whole thing in about six seconds.

Pause.

“How do you feel?”

“I feel good,” I said.

“Do you feel any different?”

“No.”

“Are you angry?”

“No.”

“Are you sad and upset?”

“No.”

“Do you see any dead children?”

“That isn’t funny,” I said.

“Great,” she said, grabbing my arm and pulling me toward the door. “Let’s go.”

We had a new hangout spot: a gravel pad surrounding a natural-gas well hidden across the street from the Sportsmen’s Shooting Center, way out of town on State Street. It was one of those large pumps that looked like a giant bobbing bird toy. One of the pieces of advice I’d been given when I left the hospital was to find new routines and avoid places and people that always led to trouble. Lake O’Dea was a great place, but it was time to move on. Laura seemed to like the gas well. We never actually saw it move or pump anything. It seemed to have been randomly plopped down in the middle of an open field. The gravel path leading from the road curved off behind a ditch and small mound, making it easy to pull in and be completely hidden from the view of passersby. We’d often lay a blanket on the gravel and stare up at the sky, sit around and talk and smoke cigarettes, or just sit in the car and listen to music. There was no one around, or any reason for anyone to be around, for a long while in either direction.

Increasingly, it wasn’t just my future we might talk about.

Laura had always been a stellar student and had great grades. There was no doubt she could go just about anywhere she wanted for college, yet she wouldn’t commit herself to anything. She would wonder aloud whether she should go to school or stay home for a bit and save money. Maybe she’d go somewhere far away to school, or maybe she’d go to one of the Kent campuses. Who knew?

As time went on, I found her lack of clear decisions increasingly hard to believe, and I’m sure it was evident in my tone. By now, in June, every time I’d bring up the subject, she seemed visibly uncomfortable.

“Who knows, I guess I’m going to have to figure something out soon, huh?” she’d say. “Hey, what are you doing on Saturday? Wanna go see Rocky Horror?”

The Rocky Horror Picture Show is something that people rooted in the modern world of YouTube and Twitter can never appreciate. It isn’t that things like The Rocky Horror Picture Show couldn’t happen today, it’s that they can happen too easily. Viral videos, photos, and websites become sensations, get millions of hits, and are forgotten in the course of a week. We have no patience for organic phenomena today. There was no email or Internet when Rocky Horror became what it was, no cell phones, no VCRs or downloads, either. It took years to formulate and spread, one person at a time, until it had morphed into a Saturday-night ritual for freaks and weirdos across the entire country. Instead of building organically over years, today something like Rocky Horror could spread in hours, if not minutes, and burn out almost as quickly.

I’m always surprised by the number of people who think the audience participation and gags in Rocky Horror were always meant to be there. They weren’t. It is a horrocious film. All the talking back to the screen and throwing stuff and squirt guns were always a way to make fun of this terrible movie.

The closest place that showed The Rocky Horror Picture Show was a dive movie theater in downtown Cuyahoga Falls, which was an absolute ghost town late on a Saturday night.

I had never seen Rocky Horror before but knew a group of older kids who had all gone a bunch of times when I was still too young to get in. I’d picked up on all the routines and audience antics vicariously through them. I also had a copy of the soundtrack album, so I knew all the songs already.

All of this led to me hitting the ground running. I did a lot of ritualized screaming, singing, and dancing on my very first viewing. Laura seemed to have a lot of fun, though she wasn’t nearly as enthusiastic about it as I was. Participation, especially group participation, really wasn’t normally her thing. For me, it was probably the most I’d ever smiled in any ninety-minute period in my life. It was being in a place with a bunch of people, being ridiculous and loud and having fun. The sense of joy and freedom was infectious. The people there didn’t give a fuck if anyone understood them or not—they got one another. They were a group of people sharing some unbridled joy over something that they all had in common but the rest of the world didn’t get at all. There was a clear sense of purpose—to have fun and let go.

A guy in full makeup and wearing a corset, fishnet hose, and insane pumps had been sitting next to us all evening, jumping up and down with us every time. After Riff Raff sent Dr. Frank-N-Furter to say hello to oblivion and the movie ended, he turned to us and extended his hand.

“Hi, I’m Jamie,” he said. “You’re new, right? Well, a bunch of us get together every week afterward at the shit-stain diner down the street for breakfast. You two bitches are welcome to come if you like.”

“This is my Vikki,” Jamie said later as we joined the group for our first diner visit.

“I’m his fag hag,” she chimed in.

“Vikki works at the dirty-book store,” Jamie said hurriedly. “If you’re ever in the mood to spend a quiet intimate evening with a large black rubber penis, Vikki is your connection.”

Vikki waved her hands whenever she burst out in laughter, which seemed to happen several times a minute. Having an awful job myself, I tried to bond with Vikki over her work.

“It really isn’t that bad,” she said. “I keep the tissues stocked and make change. Then I just read the rest of the night.”

I asked if the patrons ever tried to hit on her.

She laughed and waved. “Yeah, I really don’t think I’m what they’re looking for, if you know what I mean.”

When Vikki wasn’t laughing at everything Jamie said, she spent most of her time talking with a rather stern androgynous woman named Val who she sat with during the movie showings. Val seemed to take her Rocky Horror very seriously, acting out routines, doing dances, and singing with almost military precision. She would almost crack a smile every time Vikki burst out in laughter but otherwise sat there looking rather drill-sergeant-ish.

Throughout the diner, people would periodically switch places around the big table to converse with different others. Since we were new, many people came to sit with us and learn who we were. Even though we’d only just met these people, they immediately welcomed us as family. They were a collection of eccentrics, outcasts, homosexuals, degenerates, dramaclub officers, attention whores, and oddballs. All were square pegs wrapped in some flamboyant combination of leather, fishnet, sequins, odd hats, and tons of makeup. Laura and I never dressed up for any of our Rocky Horror excursions but still fit in pretty well, mostly because our everyday attire wasn’t that far off of what they wore on Saturday nights. Compared with the normal clientele in a late-night diner, our group seemed as if it had been beamed down from some futuristic other planet (one with a considerable investment in hairspray and eyeliner). They had nasty mouths and were funny and alive. They all seemed to have a chip on their shoulder or some baggage from years of trying to find a home in the real world. Here were the only people in Ohio who were weirder than I was.

So started a kind of ritual. Almost every Saturday night Laura and I would figure out who could get a car, then we’d drive up to Cuyahoga Falls and get to the theater for the midnight show. Afterward, we’d all head down the street to the all-night diner for breakfast.

We’d sit and drink coffee and order just enough bad food to keep from getting kicked out. The diner staff seemed to genuinely dislike us, always giving us reminders that we were the reason they hated their jobs. We talked about deep stuff and silly stuff. It was a venue to entertain one another and a forum to discuss things the rest of the world wouldn’t understand. None of us seemed particularly concerned about what went on in the others’ lives the rest of the week, but on early Sunday mornings, we would become best friends, chatting until near dawn. At some point the whole culture around the movie became almost trivial. Eventually I’d find myself kinda bored and antsy during the movie. The real attraction was hanging out at the diner afterward.

I’d been up late listening to music and reading when I heard a click come from the hallway. I looked up to see the attic door slowly open halfway and stop. After a few seconds, my stomach started to heave.

This is it, I thought to myself. At any moment, She is going to walk out beyond that doorway and corner me in this room. You’d think by now, years after this started and after my hospital stay, that I could feel fairly certain that She wasn’t coming. That, of course, is how rational people would think. But every time I’d get it in my head that She was coming—perhaps I’d just woken from a dream or heard a strange noise—it seemed imminent and unstoppable.

I tried calling out. “I’m going to close my eyes,” I said. “And if there is a ghost here, I will see it when I open them again.”

Nothing.

It happened again the next day while I was getting ready to go to work. Just a subtle click from the door latch. The door opened about a foot, then stopped. This time I rushed toward the door and swung it wide.

There was nothing there.

“If you have something to say, say it!” I yelled up the stairs. “If there is something you need to do to me, then do it. Quit fucking around!”

It happened a third time, in the middle of the night. I was lying in bed half awake when I heard the click again, then a quiet creak of the door. I sat up in my bed and looked around the corner through the doorway. The door was open about a foot. I quickly got up, closed it, then ran back to my bed and spent the next hour staring at the door to my room, waiting for Her to walk through.

Since I’d left Timken Mercy, I hadn’t told Laura or anyone else about seeing Little Girl again in my dreams. I think Laura, along with everyone who knew about Her, assumed that I had hallucinated Her or made Her up. To them, Little Girl was something left in the past. Admitting I was seeing Her was admitting that I had not left the hospital magically transformed. It was admitting that my troubles were far from over.

One night Laura and I headed out to the gas well. I was bitching about my parents and T.J. Maxx and rules and prescription drugs and anything else that I felt was oppressing me.

“Why are you so concerned with bending yourself in knots to please all these people?” she blurted out in the middle of one of my tirades.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I guess I just want to do the right thing. Right? Isn’t that what I’m supposed to be doing?”

“Fuck the right thing,” she said. “You need to spend less time worrying about what’s right and start thinking more about what’s true.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” I said.

“It means be true to yourself and you can’t go wrong,” she said. “If you worry about doing the right thing all the time, you’ll just try to make everyone happy, and that’s impossible. Just find out what is true and real; then you’ll know what to do.”

“Oh, come on. From you, that is the biggest crock of shit I’ve ever heard,” I said.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, how can you be so pious about truth when you never give anybody the truth? I mean, what do you do when we aren’t hanging out? What is your life like? Who are your friends? What is the fucking deal with you and college for this fall? We’ve spent half our free nights together for the past year and a half, and I couldn’t answer one of those questions. Why? Because you keep everything hidden.”

Pause.

“You aren’t truthful,” I continued. “All you are is evasive and vague.”

“You wouldn’t understand,” she said.

“Try me,” I said.

“Actually, I wanted to let you know … I’m leaving in a few weeks.”

“Where?”

“Baruch College … City University of New York.”

“New York? You are going to New York City?”

“Yeah.”

I couldn’t tell if I was shocked or angry or both. Deciding to go to college in New York City was not something you did on a few days’ notice. It was apparent to me that she had been planning this for months yet had chosen to keep it a secret. Whether she’d kept quiet because she was unsure what she wanted to do or because she was afraid to tell me didn’t matter. It was lame. I wanted her to know that.

“Really? Who do you know in New York City?”

“I don’t know anyone in New York City.”

I decided to fill her in on New York City (a place that I had not been to either). I talked about crime and grit and danger and the loneliness of being in a city with millions of strangers. She never said a word. She didn’t argue back. She just sat there and took it from me.

“I’m sorry you are so disappointed” was the only thing she said.

Laura gathered her things and started back toward the car, silently informing me that it was time to take her home.

We spent most of the drive not saying anything. As we turned off Route 62 toward her house, I said softly, “I guess I’m hurt that you’re leaving. But I’m more upset that you didn’t tell me.”

“Um, less than a month ago you were hanging out with a guy who thought he was Jesus,” she said. “I figured this could wait.”

I wanted to ask her why she hadn’t brought it up the month before that—or the month before that—but let it go. I was tired. I needed to get back to my parents’ house. I didn’t want to make it into a fight or act like an asshole. Saving the conversation for another night meant another day or two of pretending like I’d heard her wrong. Another day or two of pretending it wasn’t real.

A few days later Laura showed up at my front door unannounced in the middle of the afternoon. No mention of where she had been, why she was stopping by, or how she’d gotten there. No car, no friend dropping her off. No reason to be anywhere near my house.

“What are you up to?” she asked when I answered the door.

“Just stuff,” I answered.

“Can stuff wait for a bit while we go do something?”

Since neither of us had a car, we just walked to the park up the street from my house and sat on the swings.

The day after Laura’s announcement, I had had a talk with my parents. Moving to Kent was no longer an aspiration; it had to be a reality. I didn’t care what I had to do to make it happen. Cut my hair, go to church, wash the cars every day, wear a tie, sing hymns around the house—done. I would do it. If she was leaving, I figured, then I was, too. It’s harder to be left behind when you’re running away as well.

Sitting on the swing, I told her about my Kent plans, still slipping in occasional but regular passive-aggressive snipes at New York and the idea of her moving there for school. Taking the subway was dangerous. You couldn’t trust anyone. In New York there were cockroaches the size of your foot. She really never had much to say in response. She just didn’t let it bother her; she let me get it off my chest.

“I have a gift for you,” she said with a coy smile.

“A gift?”

“Yeah, something from me to you,” she said, reaching into her bag and pulling out one of her notebooks. Inside the front cover was a torn piece of paper, which she picked up, looked at for a moment, then handed to me.

It was a piece of blue-lined graph paper, probably three inches square. On it she’d written in thin pencil:

Teacher

bring me to heaven

or leave me alone.

Why make me work so hard

when everything’s spread around

open, like forest’s poison oak turned red

empty sleeping bags hanging from a dead branch.

I looked at it for a moment.

I asked her where it came from. She just stared with a slight smile emerging at the corners of her mouth.

“You don’t know?” I asked.

She puckered her lips slightly.

I continued with more questions: Did she write it? Who else wrote it? What was it called? What does it mean? Who was the Teacher? Who was taking whom to heaven? What did that part mean? I dissected the poem with questions, but Laura just stood there staring back at me, giving no indication that she planned to answer anything. She just let her smile grow slightly larger with each question.

“I don’t want to seem ungrateful, but I don’t get it,” I said. “Why are you giving me some mysterious poem, yet not telling me what it is or who wrote it or what it means?”

“Just think about it for a while,” she said. “You’ll eventually figure it out.”

Laura seemed to struggle a bit, not wanting to give anything away.

“It could be about us, I guess,” she finally blurted out. “Well,” she quickly continued, as if to pedal back. “It’s from me to you. Let’s leave it at that.”

I read it over again.

“How is this about us?” I asked. “I mean, who is who in this, and who is doing what, with what, where?”

“Just think about it for a while,” she repeated.

“Is this some kind of joke or something?” I asked. “Are you serious about this?”

She paused.

“No, it isn’t a joke,” she said.

As we sat on the swing set talking for another hour or so, I was doing exactly as she suggested. In fact, I did little else but think about the Mystery Poem. As Laura talked about some book she had just finished, I was trying to decipher what she was trying to tell me, and why now.

After she went home, I pulled out the Mystery Poem and read it again.

Part of me wondered if the protagonist’s asking to “bring me to heaven” was her way of telling me that she cared about me—or wanted to. Part of me wondered if “or leave me alone” was her way of telling me that she was giving up, tired of waiting for me to become something I wasn’t. Part of me wondered if “why make me work so hard” was her way of telling me she believed in me, but waiting for me to get my shit together was hard. Part of me wondered if this was her way of telling me she was frustrated. Perhaps the reference to empty sleeping bags on a dead branch indicated what she felt the future held for her—or me—if either of us stayed here in Canton. Maybe she was using the poem to say she loved me. Maybe she didn’t want to be friends anymore. Maybe she was trying to tell me all these things. As I pondered each, I ran through our entire history together, trying to find a way to make connections. The words of the Mystery Poem seemed like they could potentially express any or all or none of these.

I folded up the Mystery Poem and put it into my pocket.