Chapter 8. Colombia

Support to agriculture

Colombia’s level of support to farms was 13% of gross farm receipts in 2015-17, which is slightly below the OECD average. Level of support has been decreasing due to a depreciation of the Colombian Peso, the declining of producer prices, particularly after the increase of production of main agricultural products under the Colombia Siembra initiative. Market price support (MPS) is the main component of the PSE – accounting for more than 82%, over the period 2015-17. MPS is mostly stemming from the use of border measures for several agricultural products including rice, maize, poultry, milk, sugar, and pig meat. Budgetary transfers to farmers accounted for 18% of the PSE, and were mostly payments based on variable input use. Budgetary payments to general services to the sector as a whole (GSSE), have been relatively small, accounting on average for only 14% of the total support estimate (TSE). Budgetary allocations on these items include: agricultural research and knowledge transfer, infrastructure, particularly in irrigation, and farm restructuring.

Main policy changes

In 2017, support to stockholding of around 400 000 tonnes of rice was given to wholesalers with the capacity to store the grain. An income compensation payment was also given to cotton producers. Relieving financial constraints continues to be a priority and, in July 2017, the Law 1847 was approved, which provides debt rescheduling and debt relief for farmers. The implementation of this Law will take place in 2018. Budgetary transfers increased by 11% in 2017, and 16 new programmes were created, in the context of the Colombia Siembra initiative. Some programmes are on GSSE others are payments to individual farmers. For example, 12 programmes were on general services, 10 of which were directed on extension services. The other four programmes were given as support for equipment acquisition and the provision of services.

Access to land continued to be a priority and in 2017 around 3 000 land plots were formalised or legally registered under the auspices of the new ANT Agency. Efforts were taken to strengthening animal and plant health. The Colombian agency in charge of animal and plant health (ICA) established a number of new regional surveillance networks. Furthermore, a number of phytosanitary requirements to export fresh agricultural products was implemented. In December 2017, Congress also approved a law that created the National Agricultural Innovation System (SNIA), which includes both research and development, and extension services to farmers. The implementation of SNIA will take place in the coming years. In 2017, import tariffs on used agricultural machinery and equipment were removed for a period of two years. Tariffs on cotton and peanuts where also removed. Negotiations are ongoing with Japan and Turkey for the establishment of new trade agreements.

Assessment and recommendations

-

Colombia’s agricultural sector faces a wide series of structural and institutional challenges that hinder productivity and competitiveness. Underinvestment in public goods and services, poor land management, unsuccessful land tenure reforms (more than 40% of land ownership continues to be informal) and a long-running internal conflict closely linked to drug trafficking, have deeply affected the performance of the Colombian agricultural sector.

-

Comprehensive land access policy framework is necessary to stabilise the country and to promote rural development. Improved land rights contribute to long-term growth in the agriculture sector and contribute as well to promote rural development. Colombia faces the twin challenges of high concentration of land ownership and the under-exploitation of arable land. Upgrading of the cadastre system and accelerating the registration of land rights are crucial for the sector.

-

Critical areas such as infrastructure, agricultural research and development, and agricultural knowledge transfer and farm restructuring continue to receive limited support.

-

A systematic review and impact assessment of the wide array of policy instruments, and programmes to support agriculture would be important. The majority of current programmes cover very broad and different areas and are implemented through a bundle of policy instruments with unclear impact. The review should redefine and reorganise policy instruments based on evidence of costs and benefits.

-

Market price support (MPS) is the dominant form of support to producers. An assessment of the actual effects of the Price Band System should be undertaken to provide the basis for designing alternative policies that achieve the objectives set for the sub-sectors covered by the price band.

-

Improving strategic information collection on the agricultural sector is crucial for the good design of policies.

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Support to farmers (%PSE). Since the 1990s, Colombia has provided significant levels of support to its farmers. The %PSE for 2015-17 was 13.1% of gross farm receipts, but has declined to 9% in 2017. The share of potentially most distorting support is around 80% of the PSE, being linked to commodity market price support during (Figure 8.1). Effective prices received by farmers, on average, are estimated to be 12% higher than those observed in the world markets. Expenditures for general services were equivalent to 2.9% of the agricultural value added in 2015-17, larger than the 1.8% seen in 1995-97. Total support to agriculture represents 1.3% of GDP for the period 2015-17, exceeding the OECD average. The share of GSSE in TSE was 14% for 2015-17. The level of support in 2017 has declined due to a reduction of producer prices, following increasing production (Figure 8.2). The most important Single Commodities Transfers (SCTs) were benefitting rice (59% of commodity gross farm receipt), maize (47%), sugar (20%) and pig meat (25%) (Figure 8.3).

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database). http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database). http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en

Contextual information

Colombia has abundant agricultural land and fresh water, is very biodiverse and is rich in natural minerals and fossil fuels. Colombia is the fifth largest and the third most populous country in Latin America, with a surface of 1.1 million km2 and a population of 49 million people. It is the only South American country that borders both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Agriculture continues to be an important sector for the country – accounting for 16.1% of employment and 7.1% of GDP in 2016. Colombia has a dualistic distribution of land ownership where traditional subsistence smallholders co-exist with large-scale commercial farms. The sector makes a significant contribution to national exports, with agro-food exports accounting for 21.6% of all exports in 2016.

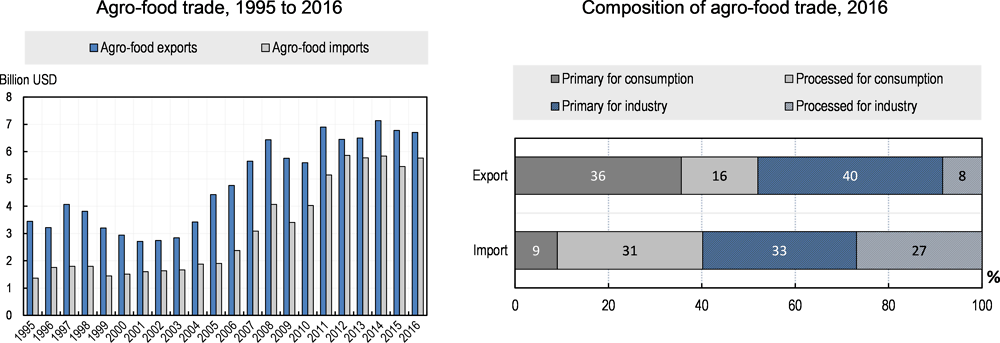

Colombia is a net exporter of agricultural and food products with a net surplus of USD 0.9 billion in 2016. Colombia’s exports of primary products are roughly equally split between those destined for final consumption (52%) and those that are sold as intermediate inputs (48%) for use in manufacturing sectors in foreign markets. Most of the exports (either final consumption goods or intermediates) are not processed prior to export. In contrast, the majority of agro-food imports (60%) are in the form of intermediates for further processing in the country.

Source: OECD statistical databases.

Low productivity undermines the sector’s competitiveness, largely driven by infrastructure deficiencies, unequal access to land and land use conflicts, as well as weak supply chains. The growth rate of the Total Factor Productivity (TFP) was only 0.7% over the period 2005-14, far below the world average. In terms of resource use, agriculture is also the main water user with a share of 60% total water use, above the OECD average. Furthermore, agriculture contributed in 2016 with 45% of GHG emissions.

Note: Primary factors comprise labour, land, livestock and machinery.

Source: USDA Economic Research Service Agricultural Productivity database. Available at: www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/international-agricultural-productivity/documentation-and-methods.aspx#excel.

|

|

Colombia |

International comparison |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1991-2000 |

2005-2014 |

1991-2000 |

2005-2014 |

|

|

|

|

World |

|

|

TFP annual growth rate (%) |

1.53% |

0.70% |

1.60% |

1.63% |

|

|

|

OECD average |

||

|

Environmental indicators |

1995 |

2016* |

1995 |

2016* |

|

Nitrogen balance, kg/ha |

.. |

.. |

33 |

30 |

|

Phosphorus balance, kg/ha |

.. |

.. |

3.7 |

2.4 |

|

Agriculture share of total energy use (%) |

6.6 |

6.9 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

|

Agriculture share of GHG emissions (%) |

44 |

45 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

|

Share of irrigated land in AA (%) |

.. |

0.9 |

- |

- |

|

Share of agriculture in water abstractions (%) |

.. |

60 |

45 |

43 |

|

Water stress indicator |

.. |

.. |

10 |

10 |

|

Source: USDA Economic Research Service. OECD statistical databases, UN Comtrade, World Development Indicators and national data. |

||||

Description of policy developments

Main policy instruments

Agricultural policy in Colombia is shaped by both the National Development Plan (PND) 2014-18 and Colombia Siembra initiative (2015). This initiative aims at raising agricultural production through an increase in the planted area (from idle land) and yields of several crops. To achieve this, resources have been redirected to key priorities such as financing, risk management, improvements on extension and technical assistance services, investments in general services, land acquisition and registration.

Market price support (MPS) continues to be the dominant form of support in the sector. MPS is provided through border protection with the use of the Andean Price Band System (SAFP). The SAFP applies to 13 commodities and their related first-stage processed products: rice, barley, yellow maize, white maize, soya beans, wheat, unrefined soya bean oil, unrefined palm oil, unrefined sugar, sugar, milk, chicken cuts and pig meat.

Furthermore, producer associations finance and administer the commodity Price Stabilisation Funds (FEP). Six commodities are covered by a fund: cotton, cocoa, palm oil, sugar, beef and milk. FEPs are funded through producer levies, but function as price-setting mechanisms that make, domestic producer prices higher than international prices. FEPs make payments to producers when the selling price of a product falls below a minimum (floor) price. When the sales price of a product is higher than an established maximum (ceiling) price, producers contribute to the FEPs. The ceiling and floor prices are established by a Council formed by stakeholders and the government, based on selected international prices for each product.

Input subsidies are another important policy measure, and dominate the budgetary transfers to producers. Several programmes provide different types of input support. For example, the Rural Development and Equity programme (DRE) has four components: 1) the Rural Capital Incentive (ICR); 2) the Special Credit Line (LEC); 3) the technical assistance support; and 4) the subsidies for land investments in drainage and irrigation. These components provide subsidies ranging from variable inputs like purchases of seed or renovation of crop plantations, to fixed capital formation such as subsidies for farm irrigation and drainage infrastructure, and on-farm services like subsidies for individual technical assistance as well as credit.

Colombia also makes use of a number of specific credit subsidies. Financing instruments relate to the access to credit (including subsidised credit interest rates), debt rescheduling and insurance programmes. The Financing Fund for the Agricultural Sector (FINAGRO) is a second-tier bank. Specific credit lines are available for: i) working capital and marketing; ii) investment; and iii) the normalisation of portfolios from which farmers have benefited from debt rescheduling and sporadic write-offs. FINAGRO also manages the Agricultural Guarantee Fund (FAG) that provides collateral to farmers, particularly smallholders. In terms of insurance, the government subsidises up to 80% of the premium, depending on the size of the farm, and whether the area to be insured has been financed with credit resources of FINAGRO.

Expenditures on general services include investments in agricultural research and transfer, inspection and control, animal and plant health, infrastructure (including farm restructuring), marketing and promotion.

Colombia has made the following commitments in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change: 1) Reduce the Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG) of the country, by 20% in relation to the projected emissions to the year 2030, with the year 2010 set as the baseline; 2) To foster adaptation in ten agricultural subsectors; 3) Six priority sectors of the economy will be implementing innovative adaptation actions; 4) Fifteen departments of the country will be participating in the agro-climatic technical tables and 1 million producers will receive agro-climatic information; 5) 100% of the national territory will have climate change plans; 6) Delimitation and protection of the 36 national areas; 7) The creation of the national system of adaptation indicators; 8) Priority basins will have management instruments with considerations of weather variability and climate change; 9) Inclusion of climate change considerations in projects of national and strategic interest; 10) Strengthening the public education strategy on climate change.

Domestic policy developments in 2017-18

Colombia Siembra continues to be the most important policy framework of the country. Around 176 000 new hectares were planted with agricultural crops in 2017. These hectares were coming mostly from idle land. The main crops planted were rice, palm oil, maize, fruit trees and beans.

In 2017, support to stockholding of around 400 000 tonnes of rice was given to wholesalers with the capacity to store the grain. The incentive responded to an overproduction in the country given the new idle land that is being used as a consequence of the Colombia Siembra framework and the Peace Agreement signed in 2016, as it provides the intrinsic security to investment on the land. An income compensation payment was also given to cotton producers. Relieving financial constraints continues to be a priority and, in 2017, more than 288 000 agricultural producers (of all scales of production) were granted loans through the FINAGRO agency. In July 2017, the Law 1847 was approved, which provides debt rescheduling and debt relief for farmers. The implementation of this Law will take place in 2018 for farmers with debts as of 2016, and the criteria of this implementation will be determined by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MADR).

Budgetary transfers increased by 11% in 2017, and 16 new programmes were created in 2017, in the context of the Colombia Siembra initiative. Twelve programmes were on general services, ten of which were on extension services. The other four programmes target individual farmers as different type of support for equipment acquisition and the provision of services.

Access to land continued to be a priority and, in 2017, more than 15 000 farmers were able to get access to land through subsidies for purchasing land and allocation of idle land by the National Land Agency (ANT), etc. Furthermore, around 3 000 land plots were formalised or legally registered under the auspices of the new ANT Agency. In 2017, the Access to Land Law was drafted and is currently being discussed in Congress; it aims at providing land to landless people that were affected by the internal conflict.

Efforts were taken to strengthening animal and plant health. In 2017 the Colombian Institute of Agriculture (ICA) agency in charge of animal and plant health, created 11 surveillance networks in 25 departments of the country. These networks monitor plague or disease outbreaks. Furthermore, 22 regulatory measures were issued on phytosanitary requirements to export fresh agricultural products.

In December 2017, Congress also approved a law that created the National Agricultural Innovation System (SNIA), including both research and development, and extension services to farmers. The implementation of SNIA will take place in the coming years.

Trade policy developments in 2017-18

On April 2017, the Superior Council of Fiscal Policy (CONFIS) removed tariffs on used (1- to 7-year old) agricultural machinery and equipment for a period of two years with the option to renew the measure for two more years. The targeted farming machinery includes ploughs, seeding and planting machines, manure spreaders, scrapers, and coffee sorting machines among others. CONFIS also reduced the cotton tariff to 0% for imports of 15 000 tonnes, classified under tariff subheading 5201003000 originated in countries with which Colombia has no current trade agreements (this until 31 December 2017). On 24 October 2016, tariff subheading 1202.42.00.00 (peanuts without roasting or cooking in another way, without peel, even broken) was removed from the soybean band.

Negotiations are ongoing with Japan and Turkey for the establishment of new trade agreements. In order to deepen the current conditions under the framework of the Pacific Alliance, the governments of Mexico, Chile, Peru and Colombia began negotiations in October 2017 as a block, with Singapore, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. The negotiations comprise deeper provisions on terms of market access, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and trade facilitation, among others.