Chapter 9. Costa Rica

Support to agriculture

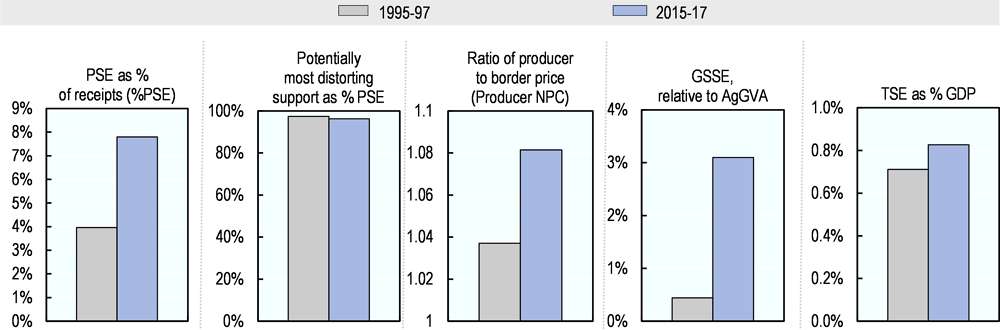

Costa Rica’s support to farmers was 8% of gross farm receipts (%PSE) in 2015-17. While this is less than a half of the OECD average, the support is almost entirely (96%) based on Market Price Support (MPS), one of the most production and trade distorting forms of support. Products with the highest MPS include rice, poultry, pig meat and sugar. The remaining 4% of support is provided mainly through input subsidies for fixed capital formation and payments for environmental services. Support to farmers (PSE) was the largest component of the Total Support Estimate (TSE) to agriculture in 2015-17 accounting for 82% of the total; the remaining 18% was based financing general services to the sector (GSSE). However, expenditures on GSSE accounted for 85% of budgetary expenditure to agricultures in 2015-17.

Main policy changes

The fundamental parameters of agricultural policy remained unchanged, the policy objectives continue to emphasise agricultural productivity and inclusiveness by focusing in the development of small-scale agriculture. Besides the price support policies, agricultural policy is mainly focused on general services to the sector such as: agricultural knowledge and innovation system, particularly on extension services; on inspection and control; and on the development and maintenance of infrastructure, particularly on irrigation. Some minor budgetary payments are provided directly to farmers as fixed capital formation subsidies and payments for environmental services.

In 2016/2017, the government began to reform the extension services (under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock-MAG), with the ambition to better link these services with the Innovation and Transfer of Agricultural Technology (INTA), the agricultural R&D institution. The National Irrigation and Drainage Service institution (SENARA) revised and changed the water pricing system and now applies a variable rate based on water availability and costs of maintaining the irrigation system.

An executive Decree 40059-MAG-MINAE-S was implemented in 2017, on Technical Regulation (RTCR) No. 484:2016. This document establishes the regulations, principles and procedures for the registration, use and control of synthetic pesticides in agriculture, and of other agricultural inputs (SEPSA, 2018).

In February 2017, the government ended an anti-dumping investigation on imports of unrefined crystal white sugar from Brazil, and decided to impose an anti-dumping measure of 6.82%, which was adjusted to 3.67%. The government also authorized the duty-free import of 6 294 metric tonnes of black beans and red beans, valid for 9 months running from September 2017 to June 2018. Another authorization was for duty-free imports of 2 602 metric tonnes of white corn. A safeguard for imports of brown rice was established in 2017. During 2017, the negotiation of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the Central American Republics and Korea was finalised. The FTA was signed in February 2018. In 2015, Costa Rica has decided to ban imports of fresh avocados from Mexico, with the aim to protect itself against the sunblotch disease (G/SPS/N/CRI/160 and G/SPS/N/CRI/162) (COMEX, 2018). The two parties continue their consultations under the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism.

Assessment and recommendations

-

Costa Rica’s producer support is still predominantly provided through border protection namely for rice, poultry, pig meat, milk and sugar. This support continues to distort both domestic markets and trade, constrains competition and, hence, productivity and competitiveness. The government should develop and communicate a strategy on how to phase out market price support to ensure a smooth transition.

-

As more than 80% of the government budgetary allocations are directed to general services, ensuring and improving efficiency of these services is fundamental. Extension services are a core function for the agricultural sector, but capacity constraints and misallocated resources reduce their effectiveness.

-

Major investments are required to improve the sector’s infrastructure, both to enhance productivity (e.g. through irrigation and drainage) and to facilitate the access to markets (e.g. through transportation, distribution, cold-chain facilities etc.).

-

Complex responsibilities and weak co-ordination among the institutions challenge the implementation of public measures and impede effective service provision to the agricultural sector. Reducing bureaucracy and improving institutional co-ordination is therefore important to ensure that support programmes are implemented in a more efficient manner.

-

Small-scale producers suffer from poor access to credit and financial tools. In addition, stringent requirements impede small-scale farms from taking advantage of available credit sources, and private commercial banks lack incentives to provide loans to small-scale farmers. While care needs to be taken to avoid moral hazard, existing credit programmes provided by the development banking system and agricultural organisations could be expanded as a first step to improve the financial infrastructure for smallholders in particular.

-

Under the framework of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the country commits to a maximum of emissions of 9 374 000 net tonnes of CO2 equivalent by 2030. The commitment implies a reduction of GHG emissions of 44%, compared to a Business as Usual (BAU) scenario. Costa Rica also has developed some agricultural sector-specific targets to help achieve the country commitments on emissions.

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Support to farmers, as measured by the %PSE has increased from 4% in 1995-97 to 8% in 2015-17, remaining well below the OECD average. Potentially most production and trade distorting support, in the form of market price support (MPS), continues to dominate and represented 96% of the PSE in 2015-17, little below its 1995-97 level. Border protection and price interventions resulted in producer prices that were 8% higher than international prices in 2015-17, on average. Around 85% of budgetary spending is on general services to the sector (GSSE). This support was equivalent to 3.1% of agricultural value added in 2015-17, a significant increase relative to 1995-97. Total support (TSE) has been increasing over time and reached 1.1% of GDP in 2015-17 (Figure 9.1). Around 87% of the total support was provided in the form of support directly to farms, while support to general services represented the remaining 13%. The level of farm support decreased by 3% in 2017, mainly due to the decrease in MPS. This decrease was due to a combination of slightly higher world prices in USD for some products and a weaker local currency (Figure 9.2). Single Commodity Transfers (SCT) represented, on average, 97% of the total PSE and are particularly important for rice (61% of gross farm receipts), poultry (35%), sugar (30%) and pig meat (31%) (Figure 9.3).

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Source: OECD (2018), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database). http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Contextual information

Costa Rica is a small country with a population of 5 million in 2016. The country’s long democratic tradition and political stability have underpinned its important economic progress – including the development of its agricultural sector. Agriculture still plays a relatively strong role in the economy, contributing 5.4% to the country’s GDP and employing 12.2% of its work force. Costa Rica has a dualism in its agricultural sector where export oriented farms coexist with smallholders producing mostly for own consumption. Costa Rica has achieved higher standards of living and lower poverty rates than other countries in the region, with a per capita income of USD 16 642 (PPP). However, inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, has increased to reach 0.48 in 2015 (WDI, 2018).

The economy has grown by around 4.2% per year since 1995, exceeding the average growth of a number of other economies in the region. Inflation has significantly declined, from 23% in 1995 to 1.6% in 2017. Unemployment, on the contrary has increased form 5% in 1995 to 8.5% in 2017. Costa Rica has developed a successful and dynamic agricultural export sector in recent decades. The country is a net exporter agro-food, with a share of agro-food exports in total exports of 45% in 2016. Almost half of Costa Rica’s agricultural exports are primary crops for final consumption, such as bananas, coffee and pineapples. The country is also an important exporter of processed products for final consumption such as pineapple juice. Almost a half of agro-food imports are processed products for final consumption.

Source: OECD statistical databases.

During the 1980s and 1990s, structural change in the agricultural sector induced rapid growth in Total Factor Productivity (TFP). However, TFP growth has decreased over the last decade and was lower than the world average. Area expansion into less productive land, ongoing farm fragmentation and limited financial and physical infrastructure were among the key contributing factors to this decline. However, thanks to increased use of primary factors and intermediate inputs, output growth has been about the global average during 2005-14. Agriculture is the main user of water resources with a share of 73% of water abstractions. Chile has a relatively high share of GHG emissions from agriculture. Environmental regulations have led to the reforestation of large parts of the country, and 25% of Costa Rican territory is now under some form of environmental protection.

Note: Primary factors comprise labour, land, livestock and machinery.

Source: USDA Economic Research Service Agricultural Productivity database. Available at: www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/international-agricultural-productivity/documentation-and-methods.aspx#excel.

|

|

Costa Rica |

International comparison |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1991-2000 |

2005-2014 |

1991-2000 |

2005-2014 |

|

|

|

|

World |

|

|

TFP annual growth rate (%) |

3.09% |

1.36% |

1.60% |

1.63% |

|

|

|

OECD average |

||

|

Environmental indicators |

1995 |

2016* |

1995 |

2016* |

|

Nitrogen balance, kg/ha |

.. |

.. |

33 |

30 |

|

Phosphorus balance, kg/ha |

.. |

.. |

3.7 |

2.4 |

|

Agriculture share of total energy use (%) |

3.9 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

|

Agriculture share of GHG emissions (%) |

48 |

38 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

|

Share of irrigated land in AA (%) |

.. |

8.8 |

- |

- |

|

Share of agriculture in water abstractions (%) |

.. |

73 |

45 |

43 |

|

Water stress indicator |

0.3 |

1.5 |

10 |

10 |

|

Source: USDA Economic Research Service. OECD statistical databases, UN Comtrade, World Development Indicators and national data. |

||||

Description of policy developments

Main policy instruments

Costa Rica’s agricultural policy priorities are articulated in three main strategic plans: i) a long-term strategy for the agricultural sector (2010-21); ii) a short-term strategy for the agricultural sector (2015-18); and iii) the corresponding National Development Plan 2015-2018 (NDP). Costa Rica’s current strategies define two overarching objectives for the agricultural sector: to reduce poverty and to increase productivity growth. To achieve these objectives, the short-term strategy prioritises five policy guidelines (or “pillars”): i) food security and sovereignty; ii) the creation of opportunities for rural youth; iii) rural territorial development; iv) adaptation to and mitigation of climate change; and v) the strengthening of the export-oriented sector. Several specific goals for increasing productivity through yield-targets have been set for some staple crops, such as rice, beans, potatoes, and milk (OECD, 2017).

The agricultural sector benefits from a government commitment to poverty reduction, agriculture and rural development, and from the provision of a range of general services for agriculture, including extension services, research and development (R&D), and plant and animal health services, with emphasis on environmental protection. For example, around 85% of total expenditures allocated to agriculture are provided through general services. However, Costa Rica maintains important border measures, in particular tariffs to several agricultural products (rice, poultry, pig meat, milk, sugar, etc.), and maintains a minimum reference price for rice. This protection generates market price support, which is by far the largest component of support to farms in Costa Rica. The country also provides minor subsidies through credit to famers at preferential interest rates, payments for environmental protection, and subsidies for fixed capital formation mostly directed to smallholders.

Under the framework of the COP21, the country commits to maximum emissions of 9 374 000 net tonnes of CO2 equivalent by 2030, with a proposed trajectory of emissions of 1.73 net tonnes per capita by the same year. The commitment implies a reduction of GHG emissions of 44%, compared to a Business as Usual (BAU) scenario, and represents a reduction of GHG emissions of 25% compared to the 2012 emissions.

To achieve these commitments under the COP21, Costa Rica has the following sector-specific targets: 1) create a low emissions agricultural sector by the identification, promotion and transfer of low emissions production technologies by 2030; 2) manage the Low Carbon Sinks (land use, reforestation, avoidance of deforestation) through the integration of rural development agenda with the Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation strategy (REDD Strategy) by 2030; 3) consolidate Carbon Price Systems (tax-market-compensation systems) consistent with country goals by 2030; 4) by 2030, consolidate the Payment for Ecosystem Services Programme PPSA with mechanisms of compensation for results, with the recognition of ecosystem services, and with the recognition of the agricultural sector as a provider of environmental benefits in cases of mitigation measures in the farm; 5) support the commercialization of agricultural products with low carbon footprint; 6) promotion of the increase in the use of wood in construction processes; 7) develop the National Adaptation Plan by 2018; 8) by 2026, improve the adaptation capacity of agricultural producers; 9) by 2026, to improve Community-based Adaptation through the Green and Inclusive Development Program, with the application of sustainable production systems in rural territories with lower human development indexes, and vulnerable to climate change; 10) by 2030 to consolidate adaptation based on ecosystems; 11) by 2030, to increase forest coverage to 60% of the national territory; 12) by 2030, to consolidate the Biological Corridor System; 13) by 2030, to consolidate the National System of Conservation Areas of Costa Rica (SINAC).

Domestic policy developments in 2017-18

The fundamental parameters of agricultural policy remained unchanged, the policy objectives continue to emphasise agricultural productivity and inclusiveness by focusing in the development of small-scale agriculture.

An executive Decree 40059-MAG-MINAE-S was implemented in 2017, on Technical Regulation (RTCR) No. 484:2016. This document establishes the regulations, principles and procedures for the registration, use and control of synthetic pesticides in agriculture, and of other agricultural inputs (SEPSA, 2018).

In 2016/2017, the government began to reform the extension services (under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock-MAG), with the ambition to better link these services with the Innovation and Transfer of Agricultural Technology (INTA), the agricultural R&D’s institution.

The National Irrigation and Drainage Service institution (SENARA) revised and changed the water pricing system from a fixed-rate fee per hectare and year to a variable rate based on water availability and costs of maintaining the irrigation system. The application of the new tariff aims at increasing the efficiency in the use of water (SEPSA, 2018).

Trade policy developments in 2017-18

In February 2017, the government ended an anti-dumping investigation on imports of sugar from Brazil, and decided to impose an anti-dumping measure of 6.82%. In view of the appeals filed before the resolution, the government adjusted the measure to 3.67%. The government also authorized duty-free imports of beans, at a volume of up to 6 294 metric tonnes of black beans in bulk and red beans. The import authorization is valid for 9 months running from September 2017 to June 2018. In addition, it authorized duty-free imports of 2 602 metric tonnes of white corn.

A special safeguard (SAS) for imports of brown rice was established in 2017 that ended in December of the same year. The safeguard was activated by volume and is imposed on imports of brown rice, with an additional 11.67% duty to the import tariff. This measure will not apply to imports from United States, Central America (except Panama), Chile and Mexico. During 2017, the negotiation of the Free Trade Agreement between the Central American Republics and Korea was finalised. The FTA was signed in February 2018 (COMEX, 2018).

In 2015, Costa Rica has decided to ban imports of fresh avocados from Mexico, with the aim to protect itself against the sunblotch disease (G/SPS/N/CRI/160 and G/SPS/N/CRI/162) (COMEX, 2018). The two parties continue their consultations under the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism.

References

COMEX (2018), Estadísticas COMEX, http://sistemas.procomer.go.cr/estadisticas/inicio.aspx.

OECD (2017), Agricultural Policies in Costa Rica, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264269125-en.

SEPSA (2018), “Annual report on agricultural policies”, Government report prepared for the OECD, San José, Costa Rica.

WDI (2018), World Development Indicators, World Bank Group, http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators.