50 The Administered World1

Horkheimer and Adorno first publicly introduced the term ‘administered world’ during a radio discussion with Eugen Kogon in 1950.2 The term became more widely known when it featured in the subtitle of Adorno’s collection Dissonanzen. Musik in der verwalteten Welt [Dissonances. Music in the Administered World], published in 1956. The notions associated with the term have deep roots in the previous evolution of critical theory. This concerns the theory of state capitalism developed by Friedrich Pollock and the concept of reason discussed especially in Horkheimer’s Eclipse of Reason but also in numerous essays written in the 1930s and 1940s. With his essay ‘Some Social Implications of Modern Technology’ of 1941, Herbert Marcuse also contributed to the genesis of the concept. In One-Dimensional Man, he arrived at conclusions similar to those of his colleagues: ‘The world tends to become the stuff of total administration’.3 The term is nevertheless associated primarily with Horkheimer and Adorno. In developed class societies, the crucial underlying notion suggests, ‘administration’ becomes a form of domination characterized by a formalizing, quantifying and categorizing mindset and an instrumental praxis. It proliferates across all sectors of society, from the sphere of production via the state bureaucracy to the culture industry, and also shapes the relationships of the individual to itself and to others. This form of administration creates an administered world.

Background in the Evolution of Critical Theory I: Planned Economies and State Capitalism

Already in the first essay with which Pollock staked his claim as one of the pioneers of emerging critical theory, published in 1932, he was concerned with ‘the colossal enterprises in industry, trade, and finance’.4 He was particularly interested in the incremental abrogation of market mechanisms reflected in the fact that states had to avoid the collapse of economic giants. The phrase ‘too big to fail’ may have been coined only in the crisis of 2008 but the concept had already been applied in 1929 and the years that followed. The need to create a new social order based on a planned economy engineered with the means of ‘total organization’ – rather than the partial organization characteristic of capitalism – resulted not from any inherent economic necessity but from the barbarous means and boundless profligacy required to maintain capitalism and develop it further.5 Planned economies depended on the ‘centralized direction of the economy’ and a unified ‘analysis of demand’.6 Moreover, it was predicated on ‘mass production in large enterprises’ and technological and organizational advancement. This included ‘the improvement of the means of communication, the development of statistical methods and technical mechanisms for their deployment, which only a decade ago would have seemed to amount to an inconceivable mechanization of bookkeeping’.7 Pollock did not suggest that within a planned economy every single enterprise had to be subjected to central tutelage. That it was ‘possible to fuse the principles of centralization and decentralization’ was the crucial point.8

Against the backdrop of the Great Depression, Pollock wondered about the degree to which it was possible to introduce elements of planning while maintaining capitalist relations of ownership.9 Was it possible, in other words, for the incremental replacement of the market by state intervention and the increasing significance of planning in the large enterprises to gel into a capitalist planned economy? To his mind, central planning and capitalist relations of property were, in principle, compatible. If ‘the power of disposal is ceded to the planning authorities’ then ownership of the means of production became ‘what in very many cases it already is today, that is, the guarantee of a more or less secure economic rent’.10 Pollock was nevertheless sceptical about the prospects of a capitalist planned economy. In no social order to date had ‘the receipt of rent at society’s expense with no discernible trade off at all been sustainable in the long run’.11

Once he developed the ideal-typical concept of state capitalism in 1941, Pollock dropped this questionable line of argument.12 This concept was designed to encompass the disappearance of the market economy and the assumption of its rationalized regulatory functions by the state planning bureaucracies, the ruling parties, and the large enterprises, on the one hand, and the preservation of the private ownership of productive wealth and the profit motif, on the other. According to this definition, the Soviet order at the time was not a form of state capitalism, nor, when it was expressly mentioned, was it subsumed under this category.13 With the advent of state capitalism, the ‘mechanics of laissez faire’ were replaced by ‘governmental command’. Political means took the place of economic ones.14 This notion of a ‘transition from a predominantly economic to an essentially political era’ paved the way for the racket theory subsequently propagated by Horkheimer.15 Given its contention that economic problems were replaced by administrative ones,16 the state capitalism concept paved the way for the theory of the ‘administered world’. Within the parameters of state capitalism, administration was defined as rational activity undertaken to implement the central plan. Its ideal was ‘scientific management’ and the principle of rationalization, which entails the economization of each and every individual activity in accordance with the principle of the most economical means, the capture of all resources with the most advanced means of data processing and, of course, the monitoring of all operations by management. The adversaries of the administered world are improvisation, muddling through, conjecture, disorder and waste.

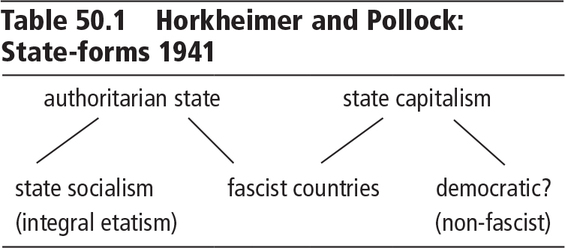

While Horkheimer did adopt the concept of state capitalism in the essays he wrote in the early 1940s, his fundamental point of reference was the ‘authoritarian state’, which, on his account, existed in two guises: as state capitalism and as state socialism or ‘integral etatism’.17 If one reads Pollock’s essay on state capitalism and Horkeimer’s discussion of the authoritarian state in conjunction, the following forms emerge:

While Horkheimer in large part accepted Pollock’s diagnosis – especially regarding the liquidation of the market economy, i.e., of the liberal phase of capitalism – his perspective was markedly more radical. No form of ‘democratic state capitalism’ featured in his account. The only hope lay in the resolute introduction of the council system.18 It alone might merit the epithet democratic. In authoritarian states, authority was exercised by the bureaucracy. The latter ‘regains the control of the economic mechanism which slipped away from the bourgeoisie under the rule of the pure profit principle’.19 That Horkheimer did not treat non-fascist forms of state capitalism in his discussion of the authoritarian state is hardly surprising. On the other hand, there can be little doubt that the diagnoses subsumed as characteristic of state capitalism were also meant to apply to those developed countries not run by one-party rule.

In Dialectic of Enlightenment, Adorno too adopted the theory of state capitalism. The notion of the administered world was clearly prefigured in the text. Human beings, so the argument went, were reduced to ‘mere objects of administration’. The latter ‘preforms every dimension of modern life including even language and perception … Alongside the capacity permanently to abolish any form of poverty, impoverishment in the form of the dichotomy between power and powerlessness is also growing beyond measure’.20

Background in the Evolution of Critical Theory II: The Concept of Reason

The principle of rationalization connects the notion of the administered world to a theme that was central to critical theory from its very inception, namely, that of reason. Already in his inaugural address as director of the Institute for Social Research of January 1931, Horkheimer identified the ‘nexus between specific existence and general reason’ as the central problem of interdisciplinary social research.21 This theme pervaded the Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung (later Studies in Philosophy and Social Science) from its first issue to its last and featured in many of Horkheimer’s as well as Marcuse’s essays. In ‘Philosophie und kritische Theorie (Philosophy and Critical Theory)’, Marcuse identified the concept of reason as the lasting legacy of the traditional philosophy drawn to a close by Hegel. It was the only category within philosophical thought through which it ‘remains connected to the fate of humanity’.22 His big Hegel book of 1941, Reason and Revolution, is also part of this story. Yet, while Marcuse’s emphasis ultimately lay mainly on the history of ideas, Horkheimer was much more clearly interested in the objective reality of reason. Needless to say, Horkheimer too depended on traditional and contemporary thought as a means of theoretical reflection upon reality. Even so, his focus was from the very beginning centred on the historically specific ‘interplay of humans in society’ as ‘the mode of their reason’s existence’.23 In this context, reason always had a twofold meaning: on the one hand, it referred to the general state of affairs, i.e., the institutions, which individuals, by pursuing their goals, reproduced – such as value, capital, the state; on the other hand, it designated the subjective position in relation to the objectivity of nature and society.

Both aspects were connected, but they were not identical and could be distinguished, to use Horkheimer’s terminology in Eclipse of Reason, as ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ reason. In modern society, social objectivity took on the guise of the ‘anonymous might of economic necessity’ to which people had to accommodate themselves.24 The subjective dimension resulted from the fact that ‘the most comprehensive accommodation of the subject to the reified authority of the economy … is the guise of reason in bourgeois reality’.25 Yet, that objectivity’s appearance as an anonymous and inherent necessity was an illusion. It actually reflected the vested interests of individuals or specific groups: ‘Production is not geared to the life of the generality as well as taking care of the needs of the individual; it is geared to the vested interest of the individual and also takes care, if need be, of the life of the generality’.26 As far as the concept of reason was concerned, the theory of state capitalism implied that the superficial mediation through functional necessities fell away and the vested interests of society became the direct object of accommodation. It was

no longer the objective laws of the market that prevailed in the activities of the entrepreneurs and precipitated the catastrophe. Rather, as resultants whose inevitability in no way falls short of the blindest price mechanisms, the conscious decisions of the managing directors execute the old law of value and thus the fate of capitalism. The rulers themselves believe in no objective necessity, even if they occasionally give that name to their machinations.… Only their subjects acknowledge the inviolable necessity of the development, which renders them yet more powerless with every decreed increase in their standard of living.27

In this new constellation, too, the concept of reason retained a critical and normative function. The difficulties of the concept ultimately originated in the fact ‘that the universality of reason cannot be anything else than the accord among the interests of all individuals alike whereas in reality society has been split up into groups with conflicting interests’.28 Matters were complicated by the insight that paved the way towards the Dialectic of Enlightenment: that an intricate, hitherto unresolved nexus existed between social domination, self-control and the domination of nature.29 The elimination of social domination that forms the utopian vision’s point of departure could be achieved only together with a reconciliation of living matter.30 The realization of reason, then, implied a new relationship not only among human beings but also between human beings and nature. Yet in modern class society the domination of nature was an imperative that had been automatized in the apparatuses of production and domination. Subjective reason, then, was not just the logic of the individual subjects in specific sets of social relations but also the logic of those relations themselves that had taken on a life of their own in the gigantic apparatuses of production. Only this made subjective reason ‘the concept of rationality that underlies our contemporary industrial culture’.31 Subjective reason could disembed itself from the twofold context of objective between reason and recognition of the wilfulness of nature and the realization of a true generality of social institutions.

Subjective reason that failed to do so was what Horkheimer, in Eclipse of Reason, termed instrumentalized reason, the guise of reason in the administered world whose crucial characteristic, as Adorno put it, was ‘the concentration of ever greater economic and social units to facilitate nescient and baleful sectional ends’.32 Whether the unquestioned ends that had taken on a life of their own were really as opaque as Adorno claimed is a moot point, however. The fundamental goal underlying those unquestioned and effectively unquestionable ends pursued by the apparatuses of production as well as educational institutions was, after all, still the production of abstract wealth and the exchange value of capital in its general guise as money. Educational institutions contributed to that goal not least by obscuring it. The valorization of value, profiteering, or growth, as it is euphemistically called, is in no way connected to any concrete form of objectified wealth.33 It would seem, alas, that Horkheimer and Adorno themselves, during the Cold War, were inclined to obscure this goal. Indeed, this may be the fundamental problem with the concept of the administered world – that it does not give the still constitutive role of the extended production of capital its due.

Administration as a Mindset and Form of Domination

The administration of the administered world is predicated on a mindset that emerged with modern science and first became social reality in the industrial application of technology in the capitalist factory. In Eclipse of Reason, Horkheimer portrayed this mindset as subjective reason developing a life of its own. Its characteristics were the principle of utility or instrumentalism and the classification and formalization of its objects. Its purpose was predetermined and supposed to be achieved ‘as completely as possible and with the least effort possible’.34 It was predicated on the application of legal norms, organizational targets and profit rates, which could not themselves be questioned with the means of instrumental reason. They were realized through the assessment of objects such as the inventory in an enterprise, the personnel, and individuals’ leisure activities. This assessment was predicated on taxonomies superimposed upon humans and goods. One draws by numbers, follows ‘abstract procedure’.35 The classificatory concepts had to allow mathematical regularities to be construed between the various data. Work processes had to be comprehensively parsed and the time requirements for each step measured and translated into a norm. In the meantime, university bureaucracies raise student data and distinguish funding sources in order to channel student streams and tailor them to targets. State bureaucracies raise data to assess claims, undertake surveillance or persecute. Commercial administrations chase data on consumer habits to facilitate more targeted advertising and arouse new cravings. Yet time and again all this effort comes up against new constraints. ‘Nothing in the administered world works seamlessly’.36 Registration and calculation turn out to be Sisyphean tasks. There are always cases that slip through the net, that precipitate the infamous need for yet more regulation, new laws and judgements, new classifications and ever more data. Today’s rationality of administration turns out to be dialectical: through its own dictates it produces the irrational elements that frustrate its calculations. The administered world turns out to be no less unbridled than the production of abstract wealth with which it is intertwined.

The utilization of data and calculations is not the only characteristic of administration as a mode of domination. To be sure, inefficient workers can be sacked and whoever seems suspicious when monitored is likely to be subjected to force. But an inherent nexus also exists between the administrative mindset and the domination of man and nature.37 This was a particular concern of Marcuse in One-Dimensional Man. This form of rationality subjugates by treating living matter that pursues its own goals as a mere object. It is interested exclusively in measurability and regularity within the registered parameters. The formation of modern science marked the decisive step in elevating the domination of nature to a principle. By denouncing the teleological dimension of the causa finalis as a form of obscurantism, one was justified in subjugating nature, as matter that had no inherent value of its own, to the ends of production. ‘The quantification of nature’, Marcuse wrote, ‘separated reality from all inherent ends and, consequently, separated the true from the good, science from ethics’.38 Inadvertently or not, by reducing deadened nature to mathematical regularities in its experiments, science was inherently connected to its technological application. Marcuse concluded ‘that the general direction in which it came to be applied was inherent in pure science even where no practical purposes were intended’.39 The application of this mindset to human beings in the fields of medicine, psychology and social engineering reduced individuals to mere objects, subsequent corrective measures designed to prevent human beings from ever being treated exclusively as objects or means notwithstanding. State and commercial bureaucracies may negotiate their goals but the basic relationship remained one of objectification and reification.40 The ideology of contract theory was unmasked for what it is when agreements could be coerced and refusal to comply carried sanctions. In the welfare state, too, the employees were subject to targets and evaluations. ‘In the medium of technology, man and nature become fungible objects of organization’, Marcuse wrote,41 and ‘this is the pure form of servitude: to exist as an instrument, as a thing’.42

The Pitfalls of a Superficial Critique of the Bureaucracy

Since the total rationalization of the administered world is a coercive function of power, a critique merely of the bureaucracy must fall short. When articulated by market liberals this critique primarily serves to weaken the legislature without being able or willing to democratize the bureaucracies (and it in any case focuses only on the state administration). In Adorno’s rather neat formulation, ‘the bureaucracy is the scape goat of the administered world’.43 On the one hand, the superficial critique of the bureaucracy fails to appreciate that a good administration, which combats corruption, can benefit society. ‘Like procedural law, the abstract procedure, which allows the bureaucrat to process each case automatically with “no respect of persons”, represents an element of justice, a guarantee, given its universal frame of reference, that arbitrariness, coincidence, and nepotism do not govern man’s fate’.44

On the other hand, the superficial critique of the bureaucracy fails to recognize that the bureaucracy is intricately connected to the mode of production. As Adorno described the process, ‘the technological work process has transcended the critical industrial sector … and proliferated life as a whole’.45 The ‘links of mediation’ that were at play here, alas, ‘have barely been exposed by research’.46 In the meantime, Harry Braverman’s study, Labor and Monopoly Capital, has filled in some of the blanks. Braverman has demonstrated compellingly how the growing significance of the office and the desire for it to function in accordance with scientific management standards follows from the evolution of the capitalist mode of production. Marx already referred to the ‘pettiest spiteful despotism’ of capital in the factory work process.47 Yet Taylorism perfected its execution of control – in the twofold sense of surveillance and domination. Taylorism was ‘the explicit verbalization of the capitalist mode of production’, a ‘science of work’, which ‘in reality is intended to be a science of the management of other’s work under capitalist conditions’.48 For Taylor, ‘scientific management’ hinged on ‘the dictation to the workers of the precise manner in which work is to be performed’.49 The experience and skill of the individual workers are thus devalued, the intellectual operations are delegated as far as possible to the planning and labour office in an attempt to create a knowledge monopoly, which can be utilized ‘to control each step of the labor process and its mode of execution’.50 With the growing need for coordination and monitoring, the demand for clerical work also increases. Bolstered yet further by the requirements of marketing and accountancy, clerical labour ‘begins to approach or surpass the labor used in producing the underlying commodity or service’.51 Crucial to Braverman’s account is the insight that the clerical work was organized in accordance with the same principles as production itself. ‘The purpose of the office is control over the enterprise, and the purpose of office management is control over the office’.52 These proven principles spread to the state bureaucracy, which, be it as tax, welfare, educational or military administrations, fulfil economic functions too and, in all of the developed industrial states, have expanded throughout the twentieth century. In the meantime, principles of scientific management have been enshrined through the state bureaucracy in areas of activity which until two or three decades ago were considered unsuited to those principles: university studies, research in the humanities and social sciences, the caring professions and social services. This trend can justly be subsumed under the concept of the administered world, provided one bears in mind the open-ended character of its totalizing momentum.

For Horkheimer and Adorno, this momentum amounted to advancing sociation and social integration.53 They subscribed to the Marxian theory that, as the domination of nature progressed, individual relations of dependency grounded organically in familial relationships or brute force were superseded by functional relations of dependency, which, like market relations, only emerged through individuals’ social activities.54 To the same degree as untreated nature disappeared or was declared inviolable and enclosed in nature reserves, social relationships were subjected to abstract norms, to the ‘alienation of the individual from itself and others’.55 This development continues as the capitalist production of value takes hold of ever new objects: communication and mobility, health and education, water provision and human genetics, animals and plants. For the reasons examined by Braverman, valorization and commodification, the transformation of the world into commodities, transpired hand in hand with the extension of the bureaucracy. As Adorno put it, ‘the integration of society has grown in the sense of an increasing sociation. The social net is woven more and more closely and there are fewer and fewer areas and spheres of so-called subjectivity that have not been seized directly and more or less comprehensively by society’.56

Self-Reification, AUTHORITARIANISM and the Atrophy of Responsibility

The administered world’s sense of totality is demonstrated with particular clarity by its imprint on the individual. The administration of human beings amounts to their objectification and reification. This mechanism is internalized, which leads to the self-reification of those compelled to accommodate themselves to the administered world. This was already the subject matter of Adorno’s aphorism ‘Novissimum Organon’ in Minima Moralia. As he put it in 1950, ‘everyone is their own clerical case worker, as it were’.57 In his essay of 1967, ‘Erziehung nach Auschwitz’ [Education after Auschwitz], he offered a condensed account of the kind of person calibrated for reification whom he also identified with the manipulative character previously introduced in The Authoritarian Personality. A manic dedication to organizational activity and efficiency, a fetish for technology, and emotional frigidity were among the characteristics of this kind of person. ‘People of this kind first make themselves resemble objects and then, if they can, others too’.58 Developments in the decades since have only confirmed the acuity of this diagnosis of self-reification. One engages in time management, learns to deal with one’s feelings, holds ‘emotional bank accounts’, and crafts the identity one needs in any given context. The term adaptation no longer refers merely to one aspect of the natural process of evolution or to one aspect of the socialization into human society that transpires instinctively through mimetic behaviour. Instead, it has taken centre stage and become a commandment and creed. One has to, and wants to, conform and this strategy boils down to a principled willingness to engage in self-reification and self-instrumentalization. ‘The process of adjustment has now become deliberate and therefore total’.59

Since human beings in the modern world are not merely the proverbial cogs in the machine but also subjects that bear responsibility for themselves in the market place, the desire of subjectivity for emotions and identification has to be taken into account. Consequently, the administered world is also the world of the cult of personality, of the principle of individuality. Preoccupation with oneself plays a considerable role. Yet the much vaunted act of taking care of oneself frequently seems lifeless – as Adorno put it, ‘the idea of a passionate human being today seems almost anachronistic’60 – and attaches itself to superficial issues, even when psychological concepts are invoked. For this phenomenon he coined the term pseudo-individualization.61 In the radio discussion in 1950, Horkheimer uttered a harsh critique of psychoanalysis, which applies with even greater justification today to its cognitive-behavioural competitors: ‘In psychoanalysis the process of administration is continued within the human being itself’.62 On the one hand, the rise of psychology and therapy demonstrated that for many, the process of adaptation was not, after all, as seamless as the functioning of the social machine would require. On the other hand, (psychoanalytic) therapy itself played an integral role in the process of alienation. In the form ‘in which it is currently practised’, Horkheimer argued, it implied ‘that human beings should feel well under the general pressure’.63

The totalized administration is also closely connected to the authoritarian character. While Horkheimer and Adorno occasionally felt compelled to relativize authoritarianism in their theoretical accounts of National Socialism, the suggestion that it is a matter of the past that has been pushed back and now leads a mere niche existence should be rejected. Man in the administered society is the authoritarian character.64 In the administered world, Horkheimer explained, human beings

always think in terms of those on top and those at the bottom. They immediately classify every person as belonging to a particular class, a particular political party, a particular country, a particular race. They think in terms of black and white. Black is the group, which is not one’s own; white is one’s own group with which everything is in order and as it should be. They feel a tremendous yearning to belong to one of these groups, which is then the good group. This results from the fact that their ego, their spontaneity, and their will power have become weak and limp and they can only get a sense of themselves when they think of themselves as a member of a strong community.65

The nexus between administration and the authoritarian characters lay not just in this mindset, however, but also in the hierarchical organization of bureaucracies. Max Weber had lent bureaucractic obedience the halo of morality:

When a superior authority insists on an order that he considers wrong, the honour of the civil servant lies in his ability to go against his own judgement and nevertheless carry out the order, under the responsibility of the superior, as conscientiously and precisely as though it did conform to his own conviction. Without this truly moral discipline and self-denial the entire apparatus would disintegrate.66

Historical experience has shown that this ‘honorable’ stance of the civil servants can facilitate the most atrocious crimes. Yet under less sinister circumstances, too, the division of labour in the social apparatuses promotes irresponsibleness and unscrupulousness. Anyone who has been involved with a social security office and has not become inured yet will be only too familiar with this tendency. Attempts to think beyond one’s own immediate remit are considered particularly counterproductive, even when the practised restraint places, say, the wellbeing of a child at risk or undermines arduous individuation processes.

The Administered World and the Culture Industry

Professionalized irresponsibleness also features in the cultural sphere. For Adorno this was exemplified by an incident that transpired early in 1952 when he protested against the republication of Heinrich Mann’s novel Professor Unrat under the title of the successful screen adaptation Der blaue Engel [The Blue Angel].67 From the material he was subsequently sent by the publisher it emerged that all parties involved had really been against the change of title. ‘Nobody is responsible’, he wrote.

This, in turn, reflects a much more fundamental phenomenon: the evaporation of guilt. The transfer of life to administration not only facilitates the perpetration of any number of atrocities without seeing oneself as a perpetrator. When an attempt is made, just for once, to hold an individual responsible, he can also make his excuses with utter subjective conviction. This effect ranges from seemingly negligible issues, like the changing of the title of a good novel into that of a bad film, all the way to outright atrocities.68

As already mentioned, the term administered world became more widely known because it featured in the subtitle of a collection of essays that Adorno published in 1956 as Dissonanzen. Musik in der verwalteten Welt. The thrust of the essays was twofold: they took issue with the ‘infantilized music’ in the Warsaw Pact states, on the one hand,69 and the culture industry in advanced capitalism, on the other. He criticized the social character of the choral and youth music movement of the 1950s, which hinged on the classification and hatred of deviation, on industriousness and on the hypostatization of community. The administered world demanded ‘functional music’ [Gebrauchsmusik], purposive and streamlined pieces.70 Horhkeimer and Adorno had already stressed the centrality of stereotypy to the administered arts and exposed its diversification – offering something for everyone – as a means of universal capture. The intensifying integration and socialization of relationships at the heart of capitalist development was particularly palpable in the culture industry. Human imagination was shaped by the dream factories, film and television foremost among them. Somebody who read a book was called upon to reproduce its imagery with his or her own imagination and thus in an individual way. If one watched a screen adaptation one was not only relieved of the imaginative labour but the images attained such force that they inevitably superimposed themselves upon the individual imagination. Subjectivity in the administered world was fundamentally characterized by the atrophy of spontaneity. It endangered the authentic production of art, which had to be wrested from the culture industry. ‘The current paralysis of musical forces’, Adorno wrote, ‘represents the paralysis of all forms of free initiative in the administered world, which is unwilling to tolerate anything outside of itself that is not integrated at least as an oppositional variant’.71 Indeed, the very way in which institutions used the term culture already bore the imprint of the culture industry:

He who says culture, also says administration […] The subsumption of phenomena as diverse as philosophy and religion, science and art, ways of living and mores and, not least, the objective spirit of an age under the one term of culture already betrays in advance the administrative glance, which collects, classifies, assesses, and organizes everything from above.72

Theoretical Precursors I: Marx and Engels

In terms of the concept’s theoretical antecedents, Marx and Engels form the first and principal point of reference for the notion of the administered world. Horkheimer in particular took up the thesis that administration would play an ever greater role and inverted its polarity.73 The need for a ‘board’ that ‘keeps the books and accounts for a society producing in common’ was already registered by Marx in the Grundrisse.74 This board was supposed to certify entitlements and engage in acts of distribution that could not be re-circulated in the primitive form of money, in other words, that were personalized and could be redeemed only by the board. Even ‘after the abolition of the capitalist mode of production but while maintaining social production’, a passage in the third volume of Das Kapital contended, ‘the determination of value continues to transpire predominantly in such a way that the regulation of labour time and the distribution of social labour among the various spheres of production and, not least, the bookkeeping that records all this, become more essential than ever’.75

On this point, Engels agreed with his friend Marx: ‘The rule over people will be replaced by the administration of objects and the direction of production processes’.76 Neither did the notion that capitalism would evolve via joint stock companies and trusts into state capitalism which would be the next preliminary step towards a socialist resolution of the conflict between the forces and relations of production diverge substantially from Marx’s thought processes.77 Not that this is a flawless line of argument, but one certainly cannot attribute it exclusively to Engels and then, looking back over the most horrendous decades of the twentieth century, shake one’s head in disbelief. And yet, even from the perspective of 1940, this construct seems irredeemably naïve. In ‘Autoritärer Staat’, Horkheimer quoted Engels’s developmental scheme – which ended with the state ‘taking over the direction of production’ – in some detail.78 What Engels had failed to see was the possibility that such a state, having become not only the ‘ideational’ but the actual ‘embodiment of the country’s entire capital’,79 could draw on repression and the loyalty of the masses to function as an authoritarian state.

The prospects Engels construed seem hopelessly naïve and utopian today:

The capitalist mode of production pushes more and more towards the transferral of the large socialized means of production into state ownership and thus itself shows the way towards the execution of the revolution. The proletariat will seize state power and transfer the means of production, initially, into state ownership. Yet in so doing it will dissipate as the proletariat and annul all distinctions and antagonisms of class and thus also the state qua state.… The intervention of state power into social relations will become superfluous in one sphere after another and gradually cease of its own accord.… The state is not ‘abolished’, it withers away.80

The forces of production would lie ‘in the hands of the associated producers’, and ‘the social anarchy of production’ that was characteristic of capitalism would be replaced by ‘a planned social regulation of production according to the needs of all and of each individual’.81

The decisive question, which Engels failed to raise, was that of how one could prevent the administration of objects from becoming the pretext for the domination of people. Its urgency was demonstrated by the development of the Russian Revolution. State socialism became, in the words of Horkheimer, the ‘most consistent form of authoritarian state’.82 Nevertheless, Horkheimer was not oblivious to the fact that integral etatism also held a promise for ‘the millions at the bottom’.83 ‘Wherever else in Europe tendencies towards integral etatism are stirring there is a prospect that this time it will not become entangled in bureaucratic domination again’, he wrote.84 Decisive were the actions of the masses themselves: ‘The radical change that will put an end to domination will reach as far as the will of those who are liberated’.85 Everything depended on the actualization of a true democracy in the form of a council system. ‘In a new society only the uncompromising independence of the non-delegates will prevent the administration from turning into domination’.86 In the radio discussion with Adorno and Kogon in 1950, Horkheimer still noted that ‘people today are in the grasp of the bureaucracy, but they need not be’.87

In the course of the Cold War, Horkheimer abandoned such hopes. He now considered ‘the tendency towards absolute administration’ and integration inescapable and irrevocable,88 and dropped the notion of ‘self-governance’, which had also been the critical vanishing point of Marcuse’s concept of bureaucracy.89 ‘As long as its development is not disrupted by catastrophes’, Horkheimer explained in 1971, ‘society, following its inherent logic, gravitates towards a state in which administration gains ever more significance at the expense of individual spontaneity so that production and the tasks it depends on are no longer reliant upon “free enterprise” but effectively turn into automated processes’. Horkheimer now assumed ‘that the path leads inexorably to total administration’.90

Theoretical Precursors II: Max Weber

The significance of Max Weber for the concept of the administered world is generally overstated. At its core, the concept drew on other sources and it predated the critical theorists’ serious engagement of Weber’s conceptualization of bureaucracy, which only occurred in earnest in the 1960s. To be sure, they too could not simply ignore Weber’s theories. Adorno and Horkheimer praised the renowned sociologist’s erudition and intellectual force. The designation ‘Weber-Marxism’ is nevertheless misleading. It was apparently coined by Jürgen Habermas and has variously been repeated since.91 Weber-Marxism is a wooden iron that forcibly conflates mutually contradictory elements without allowing their contradictions to be articulated or resolved. On the one hand, Weber’s endeavour presupposed theoretical Marxism and he owed important impulses to it. Not least, Marx had pointed to protestant Christianity as the form of religion best suited to the capitalist mode of production.92 Yet Weber also sought to create a counterweight to Marxism and maintained a polemical relationship to it.93 On the other hand, the engagement of Weber by Horkheimer and Adorno, and the same holds true of Marcuse, was fundamentally critical in nature. For one thing, in connection with his studies of protestant ethics they defended the Marxian positions Weber had opposed. They denied that the religious ideas of the Reformation played a ‘principal role in the emergence of the bourgeois world’. These ideas had not, in and of themselves, been original. Rather, ‘their momentous proliferation from the pulpit can be understood only in connection with the economically determined rise of the bourgeoisie’.94

Yet their critical discussion did not hinge merely on the defence of Marx against Weber. It also concerned the core of Weber’s theory, his concept of rationality. They did give Weber credit for having predicted the increasing bureaucratization ‘with great precision’.95 Yet for Adorno, Weber’s concept of rationality stood on its head, making him a ‘trusty mouthpiece of his class’.96 Weber’s rationality was defined in utilitarian terms. It hinged on the ‘technically most adequate means’ without any examination of the objective rationality of the ends.97 An objectively rational end, for Adorno, would be to maintain and secure the lives of ‘the socialized subjects in accordance with their unfettered potential’.98 Yet in fact, the more the rationality of means was refined and extended, the more life was impoverished and threatened. Provided everything ran ‘normally’, individual subjective interests were governed by rationality, yet the whole was uncontrollable and crisis-ridden, a game played without a safety net and at the risk of annihilation. ‘The rationality of ends and means at the individual level’, Adorno noted, ‘not only does not balance out the irrationality of the whole but … actually reinforces it’. Society as a whole continued to be at the mercy of a blind interplay of forces.99

Little is gained by responding to Adorno’s (or Marcuse’s) critique of Weber with a reference to the fact that Weber also deployed a second concept of rationality. To be sure, to the utilitarian, formal rationality he also juxtaposed a material rationality. Yet on closer inspection, it too turns out to be a matter of subjective discretion. The distinction between material and formal rationality comes nowhere close to the concept of an objective or substantive reason whose frame of reference must be society in its entirety, i.e., the true generality. According to Weber, material rationality is a rationality of values. It makes claims of an ethical, power-political or some other kind.100 Yet it is impossible to account for the legitimacy of the values in question. When Weber refers to a rationality of values he is concerned with the immanent systematic consistency of values. These criteria can also be applied to values one does not share.101 Within this scheme, partisanship for alternative values – equality vs. class interests, say, or veracity vs. national supremacy – is ultimately not subject to a rational decision.

Weber’s distinction between formal and material rationality, along with the notion of a rationality of values, falls into the realm of subjective reason, then. Of equal concern is his relationship to irrationality. Weber was blind to the irrationality, which, as the Critical Theorists demonstrated in connection with the authoritarianism of leading Reformation figures, inhered in the bourgeois spirit from its inception.102 Moreover, his rationality of ends was not only compatible with irrationality but itself characterized by a measure of irrationality. It is this nexus that renders the relationship between reason and irrationality dialectical, and it is its non-dialectical character that sets Weber’s conceptualization markedly apart from that of the critical theorists who insisted that ‘bureaucracy … is irrational’.103 This statement, which referred to the tendency of individual functions to take on a life of their own and the self-multiplication of the need for regulation, can also be generalized. If one takes the basis of economic calculation into consideration, the rationality of ends, applied to the economic realm, is irrational. As things stand, the economic handling of use values presupposes their transformation into exchange values. Yet in the exchange relationship between commodities, the relationships between those who work also appear as those between objects. Weber’s concept of rationality, Adorno argued, was naïve because he did not touch on the crucial concern: ‘in the world we inhabit, relationships between human beings, due to the structure of the exchange process’ were ‘reflected back to us, as though they were the characteristics of objects’.104

Marcuse presented a detailed critique of Weber’s concept of bureaucracy at the 15th Congress of German Sociologists in 1964. According to Habermas, he made quite an impression.105 Building on the insight that Weber’s formal rationality was itself characterized by traits of domination (see the section ‘Administration as a Mindset’, above), Marcuse focused on the contention that a bureaucracy that proceeds rationally remains dependent on an irrational power that utilizes it. The ‘bureaucracy submits to an extra- and meta-bureaucratic power … When rationality is embodied in the administration and exclusively there then this legislative power must be irrational. Weber’s concept of reason culminates in the irrational concept of charisma’.106 That said, Weber had at least recognized the risk ‘that the rational bureaucratic apparatus of administration, by virtue of its rationality, submits to an alien authority’.107 Just as the progressing domination of nature was subordinate to capital as the self-valorizing value, state (and other) bureaucracies needed a leader. ‘Disastrously’, Adorno explained in the radio discussion with Horkheimer and Kogon, ‘irrationality is rationalized’.108 Or, as he put it elsewhere, ‘rationality … falls into irrationality’s sphere of influence’.109

Habermas and the ‘Colonization of the Lifeworld’

Jürgen Habermas adopted but also contained the notion of the administered world in his concept of the ‘colonization of the lifeworld’.110 As is well known, the concept of the lifeworld was introduced by Husserl in the context of his reflections upon the Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften [Crisis of the European Sciences]. Habermas appropriated the term in order to construe theoretically a field of action within which communicative action could reside. Communicative action that transpired in the lifeworld was oriented towards common understanding and sought forms of consent that, in the modern world at least, were rationally motivated, i.e., based on arguments grounded in normative regularity, factual veracity and emotional genuineness. Any form of action oriented towards common understanding transpired in what is assumed to be a shared situation. The entirety of assumed commonalities, underlying convictions or notions that go without saying, formed the lifeworld. It was the reservoir that fed the definitions of the situation. These underlying convictions formed ‘patterns of interpretation, value and expression’ to which Habermas assigned the terms culture and language. They were not, in the first instance, thematic and could not be designated knowledge because knowledge ‘stands in internal relation to validity claims and can therefore be criticized’.111 Yet it could also transpire that the assumption of commonalities was incorrect. In that case, the definitions of the situation themselves were problematized in communicative action.

The fundamental problem with Habermas’s social theory springs from the fact that he wants to anchor communicative action and the lifeworld as its practical locus in a specific social sphere that is distinct on principle from the economic and administrative spheres. In the latter, action was strategic and instrumental, and common underlying assumptions and thought patterns that could turn out to be mutually contradictory did not seem to exist. Conversely, it is something of a stretch to imagine that gainful employment as an activity, though supposedly not communicative, belongs to the lifeworld. As ‘performance’ it certainly belongs to the functional context of the economic system.112 Since Habermas does not explicate the distinction between action and performance, one might think of the Marxian distinction between the labour process and the valorization process. Yet one of the presumptions underlying Habermas’s theory of communicative action was that Marx’s theory of value was incorrect.113 According to Habermas’s colonization theory, the lifeworld (understood in the sense outlined above) was embroiled in defensive action against the intrusion of dictates from the economic and administrative subsystems that have taken on a life of their own.114 Their imperatives, according to Habermas, were monetization and bureaucratization. By colonization he meant ‘the penetration of forms of economic and administrative rationality into areas of action that resist being converted over to the media of money and power because they are specialized in cultural transmission, social integration, and child rearing, and remain dependent on mutual understanding as a mechanism for coordinating action’.115 The core site of this colonization Habermas saw in the modern welfare state, which guaranteed freedom, on the one hand, but also had an individualizing and atomizing effect, on the other.116 Habermas also focused on the commercialization of leisure (‘mass consumption’) and the juridification of relationships within families and schools.

The fundamental problem with this concept resides in the notion that monetization and bureaucratization supposedly confront a lifeworld in which, as Habermas himself reflected and is all too evident from the reality around us, the economic and administrative principles, their ‘steering media’, throughout modern history have been firmly grounded all along.117 In Misère de la philosophie [The Poverty of Philosophy], published in 1847, Marx already pointed to the fact that ‘things, which until then had only been imparted but never exchanged, given but never sold, acquired but never bought: virtue, love, conviction, knowledge, conscience etc. … all became objects of trade’.118 This makes it difficult to argue that juridification and monetization emerged only with the welfare state and thus impinged on the lifeworld from the outside. In fact, these processes asserting modern economic principles have been at work from the outset and shape the attitudes of those they impact. In this context, monetization and juridification are intertwined. As Habermas acknowledged, the power of the economic subsystem over social services, the familiar economization of the social, was implemented by the administration in legal form.119 Yet in all spheres the economization of the social transpired in at least two phases, which could be identified with the Marxian concepts of formal and real subsumption to the exchange value.120 The economization of welfare consists not merely in the fact that one now needs to pay for services which are needed regularly, like medical or care services. This has been the case for some time and merely reflects the professionalization of the services. Decisive in the process of economization is the ingress of typically administrative forms of action into the fundamental work processes and their analysis, planning, streamlining and documentation. These are all processes that since the beginning of the twentieth century have constituted the phenomenon of economic rationalization and are well known from large industrial enterprises and their production sites and open-plan offices.

That said, Habermas’s social theory – the only influential approach in recent decades, apart from systems theory – can be understood as an attempt to establish the modern lifeworld as an independent sphere geared to rational agreement and capable of resisting the impositions of administration and commerce, though without questioning them in principle. His approach is plausible insofar as those impositions of monetization and regulation are indeed experienced by the subjects in their everyday lives as something coming from the outside. Yet the distinction, on principle, between the spheres of the capitalist economy, on the one hand, and state administration, on the other, each with their inviolable right, complemented by the lifeworld as a distinct sphere constituted by its own principle of rational agreement, is theoretically questionable.

Thinking with and beyond the Concept: Bauman and Foucault

Two concepts, developed after the death of the critical theorists, seem to confirm the theory of the administered world but also highlight certain weaknesses. In his Dialectic of Modernity, Zygmunt Bauman, while offering a deficient, apparently second-hand account of The Authoritarian Personality,121 comes fairly close to the critical theorists’ approach. According to Bauman, the Holocaust was ‘a by-product of the modern drive to a fully designed, fully controlled world’.122 Something similar could occur whenever democracy was abolished and replaced by ‘an almost total monopoly of the political state’.123 For Bauman, the ‘pronounced supremacy of political over economic and social power, of the state over the society’ was the decisive factor.124 The similarities to the concept of the authoritarian state are obvious. Given this supremacy of the state, the instrumental rationality inherent in the modern bureaucracy and the lack of moral responsibility, reflection and impetus fostered by the functional division of labour could take unrestrained effect. Bauman illustrated this by citing an expert on gas vans. ‘The bureaucratic mode of action, as it has been developed in the course of the modernizing process’, Bauman wrote,

contains all the technical elements which proved necessary in the execution of genocidal tasks.… Bureaucracy is programmed to seek the optimal solution. It is programmed to measure the optimum in such terms as would not distinguish between one human object and another, or between human and inhuman objects. What matters is the efficiency and lowering of costs of their processing.125

Here too the affinity to the critique of one-sided rationality formulated by Horkheimer, Adorno and Marcuse is obvious.

What distinguished Bauman’s approach from that of critical theory is the absence of a teleological scheme. The authoritarian or totalitarian state features not as the necessary outcome of an inexorable development but as a constant threat that can be counteracted. This corresponds to the historical experience of the post-war era. An additional concern for Bauman was the cooperation of the victims as exemplified by the actions of the Jewish Councils in the ghettos. Above and beyond the distressing example of the Jewish Councils, this behaviour constituted an element of modern sociation illustrated by today’s neoliberal welfare legislation with its ‘integration agreements’, or the ‘target agreements’ in contemporary universities.

Precisely because of its extremity, the Holocaust revealed aspects of the bureaucratic oppression which otherwise might have remained unnoticed.… Most prominent among these aspects is the ability of modern, rational, bureaucratically organized power to induce actions functionally indispensable to its purposes while jarringly at odds with the vital interests of the actors.126

The critical theorists did not return to this dimension of administrative domination in the post-war era.

In the late 1970s, Michel Foucault focused on the ideas of German ordoliberalism and sought to ground them in a history of ‘governmental rationality’ that he pursued back into the eighteenth century. We need not concern ourselves with the wilfulness of his historical derivation and its blind spots, or even his oddly flat discussion of administration.127 For our discussion here, the crucial point is that Foucault focused on the market economy, which, according to Horkheimer, Pollock and Adorno should no longer have existed. Although prices were deregulated in West Germany between 1948 and 1953,128 Horkheimer, Pollock and even Adorno, though he was more careful in his formulations,129 maintained their position that the market economy had come to an end, and refused to re-examine their diagnosis of the 1930s and 1940s in the light of new developments. There can be little doubt that this mistaken but presumably convenient conviction obstructed the further development of critical theory. While the cultural liberalization from the 1960s onwards caught those who were convinced that the trajectory towards the authoritarian state was inexorable unawares, forms of market-conform individualization against the backdrop of the welfare state were simply no longer taken into consideration. This is all the more remarkable, given that Foucault’s theory of the ‘entrepreneur of himself’130 was already anticipated in Dialectic of Enlightenment:

The more universally the modern industrial system demands of everyone that they serve it, the more all those who do not belong to the ocean of white trash … turn into wee experts, becoming employees who need to fend for themselves. As qualified labour the independence of the entrepreneur, which no longer exists, spreads to everyone admitted as a producer … and forms their character.131

That the concept of the administered world requires some adjustment should not detract from its continued heuristic and explanatory functionality. Technological developments have increased the potential for the unfolding of the trinity of registration, calculation and domination further than was remotely conceivable in the middle of the twentieth century. This holds true for labour processes within which digitization has opened up new areas of standardization and control.132 It also holds true for people’s private lives, in which the tyranny of the norm is established by the welfare bureaucracy and the culture industry. The latter relies primarily on self-help literature, the function of stars and film characters as role models, and the streamlining of the major news outlets. And it holds true, not least, for state security apparatuses, especially for the secret service, with their dystopian capacities for surveillance. In the hand of authoritarian governments they facilitate comprehensive control, intimidation and punishment.

Notes

1. This contribution is a revised and updated version of my essay, ‘Erfassen, berechnen, beherrschen: Die verwaltete Welt’, in Ulrich Ruschig, Hans-Ernst Schiller (eds.), Staat und Politik bei Horkheimer und Adorno (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2014), 129–49.

2. Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Eugen Kogon, ‘Die verwaltete Welt oder: Die Krisis des Individuums’, in Max Horkheimer, Gesammelte Schriften vol. 13 (Frankfurt: Fischer, 1989), 121–42.

3. Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man (Boston: Beacon Press, 1964), 169. See also Herbert Marcuse, ‘Das Veralten der Psychoanalyse’ [1963/68], in Schriften vol. 8 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1984), 60–78. Though he did not use the term ‘administered world’ in this text, his account and critique of the phenomena in question were very similar to those of Horkheimer and Adorno.

4. Friedrich Pollock, ‘Die gegenwärtige Lage des Kapitalismus und die Aussichten einer planwirtschaftlichen Neuordnung’, in Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 1, 1–2 (1932), 8–27, here 11.

5. Ibid., 17.

6. Ibid., 20.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid., 24.

9. Ibid., 18, 26–7.

10. Ibid., 26.

11. Ibid., 27.

12. See Friedrich Pollock, ‘State Capitalism’, in Studies in Philosophy and Social Science 9, 2 (1941), 200–25, here 209.

13. Ibid., 221, note 1, and passim.

14. Ibid., 207.

15. Ibid. See Kai Lindemann, ‘Der Racketbegriff als Herrschaftskritik’, in Ruschig, Schiller, Staat und Politik, 104–28, and Gerhard Scheit’s contribution in this Handbook.

16. Pollock, ‘State Capitalism’, 217.

17. Max Horkheimer, ‘Autoritärer Staat’ [1940/1942], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 5 (Frankfurt: Fischer, 1987), 293–319, here 300.

18. Ibid., 297, 304.

19. Ibid., 310–11.

20. Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Dialektik der Aufklärung (Frankfurt: Fischer, 1969), 45. During the Cold War, Horkheimer revised his assessment of the Soviet Union. If in 1941 the Soviet order was classified as a form of state socialism or integral etatism quite distinct from (authoritarian or non-authoritarian) state capitalism, by 1959 it too was subsumed under the category of state capitalism: ‘In Russia, however, that state capitalist state of affairs reigns which dictates that, given internal and external pressures, industrialization must transpire more quickly and the people must be made to function with more brutal means than was the case even in England in the early liberal era’ (Max Horkheimer, ‘Philosophie als Kulturkritik’, in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 7 [Frankfurt: Fischer, 1985], 81–103, here 91). This line of argument hardly seems plausible, given that there was no private ownership of the means of production in the Soviet Union. Horkheimer’s pro-Western partisanship coexisted with this contention that a ‘convergence of the two mutually hostile worlds’ was in the process of evolving (Ibid., 92).

21. Max Horkheimer, ‘Die gegenwärtige Lage der Sozialforschung und die Aufgaben eines Instituts für Sozialforschung’, in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 3 (Frankfurt: Fischer, 1988), 20–35, here 32.

22. Herbert Marcuse, ‘Philosophie und kritische Theorie’, in Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 6, 3 (1937), 631–47, here 632.

23. Max Horkheimer, ‘Traditionelle und kritische Theorie’, in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 4 (Frankfurt: Fischer, 1988), 162–216, here 177.

24. Max Horkheimer, ‘Autorität und Familie’ [1936], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 3, 336–417, here 377.

25. Ibid., 372–3.

26. Horkheimer, ‘Traditionelle und kritische Theorie’, 187.

27. Horkheimer, Adorno, Dialektik der Aufklärung, 44–5.

28. Max Horkheimer, ‘The End of Reason’, in Studies in Philosophy and Social Science 9, 3 (1941/42), 366–88, here 370.

29. See Hans-Ernst Schiller, Das Individuum im Widerspruch. Zur Theoriegeschichte des modernen Individualismus (Berlin: Frank & Timme, 2006), 204–9.

30. See Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialektik der Aufklärung, 44–5.

31. Max Horkheimer, Eclipse of Reason (New York: Oxford University Press, 1947), v.

32. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Individuum und Organisation’ [1953], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 8 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1972), 440–56, here 446.

33. See Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Werke [MEW] vol. 23, 166–8.

34. Adorno, ‘Individuum’, 441.

35. Ibid., 447.

36. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Marginalien zu Theorie und Praxis’ [1969], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 10.2 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1977), 759–82, here 772.

37. The German term for administration, Verwaltung, and the term administration, which is also used in German as a Latinate loanword, are directly connected to the concept of ruling/domination. The German term is derived from the Common Germanic ‘walten’, which means ‘to dominate, to be strong’. The term administration draws on the Latin verb ministrare, which means ‘to serve’. One should surely refrain from drawing ethno-psychological conclusions from the fact that the Germanic term perceives of the power relationship from above and the Latinate term from below. The etymology of the term Verwaltung nevertheless goes rather well with the German authoritarian state.

38. Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man, 146.

39. Ibid.

40. The concept of reification at stake here is not the same as ‘Versachlichung’ that is used by Marx in Das Kapital (see MEW vol. 25, 838).

41. Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man, 168.

42. Ibid., 33.

43. Adorno, ‘Individuum’, 446.

44. Ibid., 447.

45. Ibid., 450.

46. Ibid. ‘Bureaucratic domination is inseparable from progressing industrialization; it transfers the optimized performance capacity of the industrial enterprise to society as a whole’ (Herbert Marcuse, ‘Industrialisierung und Kapitalismus im Werk Max Webers’, in Schriften vol. 8, 79–99, here 90–1).

47. MEW vol. 23, 674.

48. Harry Braverman, Labor and Monopoly Capital. The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century [1974] (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1998), 60, 62[emphasis in the original].

49. Ibid., 62 [emphasis in the original].

50. Ibid., 82 [emphasis in the original].

51. Ibid., 209.

52. Ibid., 211.

53. See Per Jepsen, Adornos kritische Theorie der Selbstbestimmung (Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2012), 111, 134, 143. Jepsen identifies the administered world as the key concept underlying the notion of a ‘comprehensive social integration of the individuals’.

54. See MEW vol. 42, 89–98.

55. Ibid., 95.

56. Theodor W. Adorno, Philosophische Elemente einer Theorie der Gesellschaft [1964], Nachgelassene Schriften vol. IV.12 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2008), 106.

57. Adorno, Horkheimer, Kogon, ‘Die verwaltete Welt’, 124.

58. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Erziehung nach Auschwitz’ [1966/67], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 10.2, 674–90, here 684.

59. Horkheimer, Eclipse of Reason, 95.

60. Adorno, Horkheimer, Kogon, ‘Die verwaltete Welt’, 129.

61. Ibid., 134.

62. Ibid., 130.

63. Ibid., 132. For a more differentiated account, see Hans-Ernst Schiller, Freud-Kritik von links. Bloch, Fromm, Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuse (Springe: zu Klampen, 2017), 9–10, 243–4.

64. See Adorno, Horkheimer, Kogon, ‘Die verwaltete Welt’, 136.

65. Ibid., 137.

66. Max Weber, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft [1922] (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 51972), 833.

67. See Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Ein Titel’, in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 11 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1974), 654–657.

68. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Unrat und Engel’, ibid., 658–60, here 659.

69. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Die gegängelte Musik’ [1953], in Dissonanzen. Musik in der verwalteten Welt (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1982), 46–61.

70. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Kritik des Musikanten’ [1954], ibid., 62–101, here 70.

71. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Das Altern der neuen Musik’ [1954], ibid., 136–59.

72. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Kultur und Verwaltung’ [1960], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 8, 122–46, here 122.

73. Ulrich Ruschig, ‘Weiterdenken in marxistischer Tradition: Die Lehre vom autoritären Staat’, in Ruschig, Schiller, Staat und Politik, 73–103.

74. MEW vol. 42, 89.

75. MEW vol. 25, 859.

76. MEW vol. 19, 224. Even Adorno maintained that ‘a rational, transparent, truly free society could no more do without administration than it could without the division of labor more generally’ (Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Gesellschaft’ [1965], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 8, 9–19, here 17).

77. See MEW vol. 25, 452.

78. MEW vol. 19, 221.

79. Ibid., 222.

80. Ibid., 223–4. Emphasis in the original.

81. Ibid., 223.

82. Horkheimer, ‘Autoritärer Staat’, 300.

83. Ibid., 303.

84. Ibid., 301.

85. Ibid., 303.

86. Ibid., 313.

87. Adorno, Horkheimer, Kogon, ‘Die verwaltete Welt’, 122.

88. Max Horkheimer, ‘Verwaltete Welt. Gespräch mit Otmar Hersche’ [1970], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 7, 363–84, here 377.

89. Herbert Marcuse, ‘Some Social Implications of Modern Technology’, in Studies in Philosophy and Social Science 9, 3 (1941/42), 414–39, here 432.

90. Max Horkheimer, ‘Zur Zukunft der kritischen Theorie. Gespräch mit Claus Grossner’ [1971], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 7, 419–34, here 420–1.

91. Jürgen Habermas, ‘Drei Thesen zur Wirkungsgeschichte der Frankfurter Schule’, in Axel Honneth, Albrecht Wellmer (eds.), Die Frankfurter Schule und die Folgen (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1986), 8–12, here 9.

92. MEW vol. 23, 93.

93. See Adorno, Philosophische Elemente, 20; ‘Marginalien’, 776. For a critical assessment of Weber’s analysis of the ‘spirit of capitalism’, see Heinz Steinert, Max Webers unwiderlegbare Fehlkonstruktion. Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus (Frankfurt: Campus, 2010).

94. Max Horkheimer, ‘Egoismus und Freiheitsbewegung’ [1936], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 4, 9–88, here 44.

95. Adorno, Philosophische Elemente, 21.

96. Adorno, ‘Marginalien’, 775.

97. Adorno, Philosophische Elemente, 21.

98. Adorno, ‘Marginalien’, 775.

99. Adorno, Philosophische Elemente, 201.

100. Weber, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 45.

101. Max Weber, Wissenschaft als Beruf [1919] (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1995), 37–8.

102. See Horkheimer, ‘Egoismus und Freiheitsbewegung’, 59; Herbert Marcuse, ‘Ideengeschichtlicher Teil’, in Max Horkheimer (ed.), Studien über Autorität und Familie (Paris: Alcan, 1936), 136–228; Erich Fromm, Escape from Freedom (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1941), chapter 3.

103. Adorno, ‘Marginalien’, 776.

104. Theodor W. Adorno, Philosophie und Soziologie [1960], Nachgelassene Schriften vol. IV.6 (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2011), 99.

105. Jürgen Habermas, ‘Jüdische Philosophen und Soziologen als Rückkehrer in der frühen Bundesrepublik. Eine Erinnerung’, in Im Sog der Technokratie (Berlin: Suhrkamp 2013), 13–26, here 25–6.

106. Marcuse, ‘Industrialisierung und Kapitalismus’, 92.

107. Ibid., 94.

108. Adorno, Horkheimer, Kogon, ‘Die verwaltete Welt’, 127.

109. Adorno, ‘Individuum’, 445.

110. Jürgen Habermas, The Theory of Communicative Action vol. 2 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1987), 322.

111. Ibid., 400.

112. Ibid., 335.

113. See ibid., 202, 338–43; Hans-Ernst Schiller, ‘Zurück zu Marx mit Habermas. Eine Aktualisierung’, in An unsichtbarer Kette. Stationen kritischer Theorie (Lüneburg: zu Klampen, 1993), 152–81, here 154–5.

114. Habermas, Theory, 356.

115. Ibid., 322.

116. Ibid., 347–51.

117. Ibid., 343.

118. MEW vol. 4, 69.

119. Habermas, Theory, 342.

120. MEW vol. 23, 533.

121. Zygmunt Bauman, Modernity and the Holocaust (Cambridge: Polity, 1989), 152–3.

122. Ibid., 93.

123. Ibid., 113.

124. Ibid., 112 [emphasis in the original].

125. Ibid., 104.

126. Ibid., 122 [emphasis in the original].

127. Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 107–10.

128. Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 80, 87.

129. Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Theorie der Halbbildung’ [1959], in Gesammelte Schriften vol. 8, 93–121, here 117.

130. Foucault, Birth of Biopolitics, 226.

131. Horkheimer, Adorno, Dialektik der Aufklärung, 115.

132. See Matthias Martin Becker, Automatisierung und Ausbeutung. Was wird aus der Arbeit im digitalen Kapitalismus? (Wien: Promedia, 2017).