Chapter 1

The Individualist

Steve Jobs as Howard Roark, the man who reinvented four whole industries just because it was so cool

“I don’t intend to build in order to serve or help anyone. I don’t intend to build in order to have clients. I intend to have clients in order to build.”

“How do you propose to force your ideas on them?”

“I don’t propose to force or be forced. Those who want me will come to me.”

—The Fountainhead

Who is Howard Roark?

In The Fountainhead, Howard Roark is a courageous young architect. Ayn Rand presents him from beginning to end as her ideal man, the complete individualist who lives by his own standards and for his own sake, whose work is an end in itself simply because he loves doing it, and who is utterly indifferent to the opinions of anyone else.

Roark’s architecture is boldly original, inspired by his own personal vision. To succeed, he must rebel against the conventions of his era. His architecture of individual inspiration must compete against expectations that architecture should borrow from collectively established classical precedents. At the same time, he has to overcome terrible setbacks at the hands of enemies who want to destroy him, because he symbolizes the individual versus the collective.

His worst enemy is Ellsworth Toohey, an architecture critic for the tabloid newspaper the Daily Banner with a web of connections in the arts, high society, government, and unions. He is a madman seeking to rule the world through collectivism, starting by corrupting its intellectual and moral standards. He uses his influence to promote the careers of incompetent architects, and he directly thwarts Roark’s career with various ruses engineered to discredit him.

In a typical story, the conflict between Roark and Toohey would end in a fistfight atop an unfinished skyscraper designed by Roark, with Toohey plunging to his death, to Roark’s great satisfaction. But Roark is such an utter individualist, he has no interest in defeating Toohey. In one of the book’s most memorable scenes, at a low point when Toohey has nearly destroyed Roark’s career, the two of them meet by chance. Ever the collectivist who can’t resist defining himself through others, Toohey asks Roark to tell him honestly what he thinks of him. Roark, the man who lives entirely by his own opinion of himself, simply says, “But I don’t think of you.”

Roark triumphs over all opposition, and goes on to build the tallest skyscraper in New York. All the struggles are forgotten, mere distractions incapable of impacting a true individualist. At the end, Roark is the end—an end in himself, as each of us is.

When Steve Jobs took the stage in October 2001, he was a man resurrected, returned home from a classic hero’s journey, still true to his singular vision, but battle-hardened from 12 years wandering the business wilderness as a castoff from the tribe he founded. He was grayer and leaner, yet still sharp-edged like tempered steel emerging from the fire, himself the sword the journeying hero forges in the great myths.

Or more exactly, here was Howard Roark—Ayn Rand’s brilliant and rebellious architect hero from The Fountainhead—returning to the city to erect a stunning skyscraper embodying his own epoch-making vision, after being forced to labor in a granite quarry merely to survive.

Here was the intransigent individualist who invented a worldwide culture of personal computing, and was unceremoniously ousted from the seat of his creation by collective forces bent on harnessing and diffusing his disruptive vision through committees and opaque corporate processes. Along the way, he had a brush with financial death and went on to revolutionize a second industry—only to be recalled to rescue his original creation from the brink of collapse. Jobs was back to lead the rebirth of Apple Computer, clear the debris left by the collective that had ousted him, and rebuild his masterwork on the solid foundations of his individual vision, as he first had 17 years before.

He was close-cropped, scruffy, and dressed in his now-signature black mock turtleneck and jeans; gone were the suit coat, button-down shirt, bow tie, and boyish mop of hair from his 1984 inaugural Macintosh presentation. Gone, too, were the thematic Chariots of Fire music and talking computer gimmicks amid a cheering auditorium packed with thousands of devotees. Instead, Jobs cast a deep resonating spell of low-key personal charisma—the kind that captures and holds an audience rapt with a mere whisper.

The new uniform was deliberate. On one level, Jobs was subordinating his corporeal body to his visionary creations by shedding props and presentational artifice to allow a clearer focus on the product of his mind. The question was not “What would Steve wear?” but “What revolutionary new idea will he present today?” It was also symbolic of his simplified approach to Apple upon his return as interim CEO in 1997, when he quickly pared the growing number of foundering product groups from 15 down to a focused three1 while slashing inefficient overhead, laying off employees, and repopulating his board of directors with handpicked replacements, including Larry Ellison of Oracle and former Apple sales head Bill Campbell, then CEO of Intuit.2

In his signature presentation style, Jobs began his homecoming pitch to a small assembly of attendees at an Apple Music event. With a relaxed and unhurried ease he spoke of the market, competition, underlying technology, and the recipe for success in leveraging the Apple brand. In a seamless and nearly undetectable transition to aesthetics, he then began describing the design and usability of an entirely new-breed model of music accessibility. As he built to a crescendo, the audience was salivating in suspense. “Durable. Beautiful. And this is what the front looks like. Boom!” he exclaimed. “That’s iPod. And I happen to have one in my pocket.”

Yet the moment had even deeper meaning than the introduction of a cool new product. It was evidence of how Jobs’s entire existence symbolized right and left brains harmonized—analytics and creativity coexisting in a symbiotic blend of productive energy focused on the output of human creation instead of the cumbersome tools used to hammer those ideas into reality. He had spent a lifetime transcending the chasm between silicon-based technology and carbon-based humans. The world called that the “user interface.” To Jobs, it was a barrier, a gap, and his vision was to make that gap seem nonexistent. And now he was doing it again, with a revolutionary product of his unique mind that would transform the popular culture of the world.

He once called the personal computer (PC) “the equivalent of a bicycle to our minds” as a metaphor for human ingenuity’s ability to leverage our physical capabilities beyond anything in the natural world.3 A person on foot is quickly outpaced by most of the animal kingdom, he would explain. When that same person conceives and designs a set of wheels connected by gears and pedals, he or she becomes the most efficiently self-mobile creature on earth. But just as a bicycle without a rider is a mere hunk of metal, a computer can amplify the intellect only when a human mind is powering it. This interface between mind and machine is where Steve Jobs lives.

According to Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, “He was never driven by a vision of a better world; he was driven by a vision of himself as a person whose decisions guide the world. He wanted to build a device that moved the world forward, that would take people further. He wanted to build a reality that wasn’t there. He wanted to be one of the important ones. He either likes what he’s looking at or he doesn’t. He’s not concerned with what contribution he’s making. He wants to astound himself, for himself.”4

Ayn Rand‘s first great novel, The Fountainhead, was built around such a man, a supreme individualist—or “egoist” in Rand’s terms—Howard Roark. In the words of Roark, “I can find the joy only if I do my work in the best way possible to me. But the best is a matter of standards—and I set my own standards. I inherit nothing. I stand at the end of no tradition. I may, perhaps, stand at the beginning of one.”

He’s been referred to as a charismatic boy wonder, the Alpha Adolescent, a cultural phenomenon, a consumer technology impresario, an adroit chief executive, a cultural revolutionary, a man with three faces, a zealot, the enfant terrible, an arbiter of popular culture, a temperamental micromanager. Yet he is simply an individual—an individual who dares to shape the world in accord with what Roark would call his “unborrowed vision” and his “independent judgment.”

Like Rand herself, Jobs dares to judge the world in binary terms, in what Rand would call the Aristotelian mode of determining either-or. Products, in his view, are either “insanely great” or “shit.” One is either dying from cancer or “cured.” Subordinates are either geniuses or “bozos,” either indispensable or irrelevant.5 And like Rand’s iconic individualist Roark, Jobs works for his own reward and satisfaction in his own unbending terms. He returned to lead Apple, accepting a salary of only $1, saying, “The only purpose for me in building a company is so that it can make products.”6 And like Roark, Jobs doesn’t rely on the opinions of others to define his own views. He has the self-confidence to know that all great ideas throughout history have sprung from the intellect of a single individual. “The mind is an attribute of the individual. There is no such thing as a collective brain,” said Howard Roark.

Jobs doesn’t see himself creating something new as much as he is discovering what others can’t see. Like the myth of Prometheus and his discovery of fire, Steve is constantly surprising the world by meeting the needs and desires that people never knew they had. Comparing Jobs with Polaroid inventor Dr. Edwin Land, former Apple CEO John Sculley said, “Both of them had this ability not to invent products but to discover products. Both of them said these products have always existed—it’s just that no one has ever seen them before. We were the ones who discovered them. The Polaroid camera always existed, and the Macintosh always existed—it’s a matter of discovery.”7

Yet for Jobs such discoveries are, of necessity, the discovery of himself. “If I asked someone who had only used a personal calculator what a Macintosh should be like, they couldn’t have told me,” Jobs once explained. “There was no way to do consumer research on it, so I had to go and create it, and then show it to people, and say now what do you think?”8 Apple marketing chief Mike Murray observed, “Steve did his market research by looking into the mirror every morning.”9

Anyone who has ever been curious enough to disassemble an iPod quickly realizes it looks the way it does on the outside because of what’s inside. The economy of space, the use of materials both durable and stylish, the most leading-edge components of the day, the physical layout, and the user interface are all unique to the end function—making software manifest in the physical world while simultaneously making it invisible to the user. In short, Apple products look a certain way because they have to.

According to Sculley, “Steve’s brilliance is his ability to see something and then understand it and then figure out how to put it into the context of his design methodology—everything is design. He’s a minimalist and constantly reducing things to their simplest level. It’s not simplistic. It’s simplified. Steve is a systems designer. He simplifies complexity.”10

Or in describing Howard Roark’s architectural design mentor Henry Cameron, “He said only that the form of a building must follow its function; that the structure of a building is the key to its beauty; that new methods of construction demand new forms; that he wished to build as he wished and for that reason only.”

Jobs has spent a lifetime living by Roark’s own singular rulebook not as the designer of buildings, but as the architect of a new approach to technology. Or in Roark’s words, “The purpose, the site, the material determine the shape. Nothing can be reasonable or beautiful unless it’s made by one central idea, and the idea sets every detail. . . . Its integrity is to follow its own truth, its one single theme, and to serve its own single purpose. A man doesn’t borrow pieces of his body. A building doesn’t borrow hunks of its soul. Its maker gives it the soul.”

Steve Jobs was born on February 24, 1955, in San Francisco, California. His mother was an unmarried graduate student who gave him up for adoption to Paul and Clara Jobs, the couple Steve would always consider his true parents even after reconnecting with his genetic lineage later in life. The adoption almost fell through. Steve’s biological mother initially refused to sign the adoption papers, insisting that her son be adopted by college graduates. Clara had never graduated from college. Paul wasn’t even a high school graduate. Steve’s mother eventually relented when the Jobses promised her they’d send Steve to college.11

Paul, the no-nonsense son of a Midwestern farmer, had dropped out of high school and enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II, where he mastered the trade of engine mechanics. With his crew cut and tattoos, Paul exuded a hearty and productive blue-collar pride. Possessing an innate mechanical aptitude, Paul loved to tinker with cars. He would buy old junkers and then spend weeks fixing them up to resell at a profit. He was known as a tough negotiator.12

It was an ironically concrete beginning for an abstract intellect like Steve’s, but that solid family foundation rooted him in an ethic of hard work and personal responsibility. His father’s pursuit of profit through hard-nosed entrepreneurship and productive value-added clearly rubbed off on young Steve, who would grow to become an astute and tough-minded deal maker himself. Despite little formal education of his own, Paul also encouraged his son’s curiosity and interest in the new field of electronics.

Like many gifted kids, Steve was a rambunctious child who quickly became bored with tedious schoolwork geared toward the middle of the student bell curve. Under the wing of an insightful teacher who recognized Steve’s talent, he skipped fifth grade altogether but soon found himself a young brainiac at a rough-and-tumble middle school in lower-middle-class Mountain View, California, with a greater focus on preventing fistfights than cultivating the mind. At age 11, Steve patently refused to go to school and held his ground with his parents.13 As a result of what would become his trademark persistence in eliminating obstacles in the way of his vision, his family finally relented and relocated in order to enroll Steve in the more upscale, academically focused Cupertino Middle School.

Steve was growing up in the heart of what would become known as Silicon Valley, already in the late 1960s a vibrant epicenter of electronics companies springing up to service NASA’s Apollo space program. It was a fresh field fertilized by new silicon transistor and integrated circuit technology that fostered entrepreneurial zeal and new business rules. The Jobses’ new neighborhood was populated with engineers who filled their garages with workbenches and spare electronics parts. Age and appearance didn’t matter to these technological tinkerers, and they welcomed the opportunity to share information and hardware with an eager and inquisitive kid like Steve when he came around to check out their latest projects.

Conversely, Steve never seemed intimidated by adults despite his youth and inexperience. Once, while working on an electronics project, he realized he was short on parts. Undeterred, he picked up the Palo Alto phone book and cold-called Bill Hewlett, one of the founders of Hewlett-Packard (HP). Bill answered the phone and chatted with Steve affably for a while, then ended up supplying the parts needed to complete Steve’s project. It was a determination and gumption that would become a Steve Jobs hallmark. Once he set his sights on an objective, he would wade right in, go for the top decision maker, and persist relentlessly until he succeeded.

It was in the garage of Steve’s school buddy and fellow “wirehead” Bill Fernandez where he met Steve Wozniak, the son of an engineer at Lockheed’s Missiles and Space Division in Sunnyvale. Five years Jobs’s senior, “Woz,” as he had been known since grade school, was a brilliant technician and avid prankster who had been kicked out of the University of Colorado after hacking the university’s computer system. By the time he and Jobs met, Woz and Fernandez had already built their own personal computer from surplus parts in Woz’s garage. It was rudimentary at best—a raw circuit board flashing lights in response to user-thrown switches and hardwired logic circuits—but it was a device Woz created on his own a full five years before comparable home hobby computer kits became commercially available. Woz had the technical genius, and Jobs had the vision and hustle. It was an auspicious meeting that would eventually transform their lives, and the world.

With the end of high school fast approaching, Jobs set his sights on the liberal arts mecca of Reed College in Portland, Oregon. He seemed to embrace the counterculture of the early 1970s—a belief in individuality and a refusal to accept established convention or be intimidated by it. “Steve had a very inquiring mind that was enormously attractive,” remembers Jack Dudman, Reed College’s dean of students at the time. “You wouldn’t get away with bland statements. He refused to accept automatically received truths. He wanted to examine everything himself.”14

Jobs’s drive applied only to subjects he cared about, however. After only one semester at Reed, he found himself failing out of his core freshman classes. Like Howard Roark, who got himself expelled from architecture school, he found that traditional academics offered no value to his internal vision. So in characteristic Jobs style, he dropped out of school and got a refund of his tuition. Instead of returning home, however, he stayed on campus attending classes of his own choosing for free while living in vacant dorm rooms. One of his most notable classes he audited during this time was calligraphy. It was a fascinating window into functional art that Jobs credits with inspiring the first typefaces for the iconic Macintosh computer he would later invent.

Back home as a college dropout in the summer of 1974, Steve saw an employment advertisement for video game maker Atari. According to Atari’s chief engineer, Al Alcorn, a human resources rep came to him one day to tell him that some rumpled-looking hippie wouldn’t leave the building until they hired him. Jobs’s sheer force of will and determination brings to mind Howard Roark’s meeting with architect Henry Cameron for his first job. Cameron was known as a mean son of a bitch, but Roark was as fearless with him as Jobs was with Alcorn:

“I should like to work for you,” Roark said quietly. The voice said “I should like to work for you.” The tone of the voice said “I’m going to work for you.”

“I don’t know why I hired him,” remembers Alcorn, “except that he was determined to have the job and there was some spark. I really saw the spark in that man, some inner energy, and attitude that he was going to get it done. And he had a vision, too. You know, the definition of a visionary is ‘someone with an inner vision not supported by external facts.’ He had those great ideas without much to back them up. Except that he believed in them.”15

At Atari, Jobs would work nights on a variety of projects and was a quick study. When a problem came up in Germany, Alcorn gave Jobs a quick primer and sent him there. Jobs solved the problem in Germany in two hours and then made his way to India for a prenegotiated spiritual sabbatical of sorts.

Jobs was still exploring, trying to find some hidden truth or resolve some inner conflict born of his adopted heritage or unique brand of intellect. After tramping around the subcontinent, contracting scabies, lice, and dysentery, he found the experience more raw and disturbing than enlightening. “It was one of the first times that I started to realize that maybe Thomas Edison did a lot more to improve the world than Karl Marx and Neem Kairolie Baba put together,” Jobs recalls.16

Back at Atari, Jobs returned to the business of computer electronics with renewed vigor. Even now, it was apparent that he was technically astute, but no engineering genius. His value lay in his creative vision and his persistence. Around Steve, it seemed anything was possible. It was a trait some employees would refer to as the Jobs “reality distortion field.”17 When asked to estimate the time required for him to complete a project, Jobs would quote a schedule of days and weeks instead of months and years. It was an intensity of work focus he would carry for the rest of his career.

He also renewed his friendship with Woz, who was then working at Hewlett-Packard. Jobs would sneak Woz in at night to work on projects for him in return for free playtime on the latest Atari video games. In one 48-hour stretch, Woz designed the game Break-Out with unprecedented economy, using a surprisingly small number of chips. Jobs paid Woz a fraction of the commission for doing essentially all of the work. Some critics would later claim this as typical of his approach to business: taking credit for others’ creations. Yet it’s a bit like confusing the architect with the bricklayer. One creates the vision, while the other solves problems to fit the vision. Without the driving force of the uncompromising visionary—imagining the project to begin with, then harnessing the resources and securing the deals—no nascent idea would see the commercial light of day.

Howard Roark explains it perfectly: “An architect uses steel, glass, concrete, produced by others. But the materials remain just so much steel, glass and concrete until he touches them. What he does with them is his individual product and his individual property. This is the only pattern for proper co-operation among men.”

At the time, powerful mainframe computers were still the exclusive domain of governments, universities, and large corporations. Usage time was so precious it had to be purchased by the hour. But with the increasing availability of electronic components and know-how, hobbyists began tinkering like early ham radio operators. In 1975 a group of local enthusiasts formed the Homebrew Club to split the cost of pricey computer kits, share information, and collaborate on ideas. With his acumen in acquiring components, his father’s lessons in deal making, and Wozniak’s brilliant engineering talent, Jobs was eager to play the next business angle and profit from the emerging field.

Woz had just developed a prototype computer board with the ability to drive a color television display. Inspired, Jobs saw the commercial potential for an inexpensive home computer that did far more than the rudimentary Altair featured on the cover of Popular Electronics as the first “personal” computer, which did little more than light up a string of bulbs in response to binary arithmetic hand coded into the machine through a series of throw switches. Recognizing the need for a marketing angle, Steve dubbed Woz’s machine the “Apple” in honor of a hippie apple farm retreat he had visited in Oregon.

Sensing commercial potential, on April Fools’ Day in 1976 he and Woz incorporated Apple Computer. To buy their first batch of parts, they scraped together $1,500 in part by hawking Woz’s expensive HP calculator and Job’s VW bus.18 Then it was time to hustle, which was what Jobs did best.

Paul Terrell had recently started the Byte Shop, which would become the first chain of retail computer stores. A frequent attendee at Homebrew Club meetings, Terrell was in search of new products to stock his fledgling store shelves. Impressed with Woz’s creation during a Homebrew demo, he arranged for Jobs to supply 50 fully assembled computer boards at $500 a pop. Despite his young age and apparent lack of credentials, Jobs managed to cajole a local parts supplier into extending him a 30-day line of credit after the supplier confirmed the order with Terrell. Scruffy youth was no concern in the Valley in those days. Business was business.

Terrell commissioned a local cabinetmaker to build a wooden case to house the board for display purposes. An early print ad touts the Apple-I as “The First Low Cost Microcomputer System with a Video Terminal and 8k Bytes of Ram on a Single PC Card.” Selling at a retail price of $666.66, the headline benefits read, “You Don’t Need an Expensive Teletype” and “No More Switches, No More Lights.”19 By the end of the year, the two Steves had delivered 150 Apple-I’s for $75,000 in revenue. They were on their way.

Over Labor Day weekend Jobs and Woz were offered booth space at the very first national microcomputer show, called Personal Computing 76, in Atlantic City. At the time, it was still anyone’s guess whether the embryonic personal computer could survive in a world dominated by industrial-strength mainframes and hungry corporate giants—and if it did survive, which firms would take the lead. Big names in electronics like Commodore, Texas Instruments, and RadioShack’s parent Tandy were all on the prowl for ways to enter this new market. Among the personal computers displayed were the Altair (running a version of the BASIC computer language coded by Bill Gates at Microsoft—himself an embryonic Randian hero, as we document in Chapter 5, “The Persecuted Titan”) alongside Processor Technology’s Sol, a self-contained unit in a sleek metal case with integrated keyboard. The Apple-I looked like a crude and amateurish cigar box by comparison.

The show lit a fire in Jobs’s brain as he started to understand the marketing and competitive value of an integrated finished product targeted to a mainstream consumer, versus a collection of components and boards geared toward basement hobbyists. He returned to the workshop with a vision that would leapfrog the competition in function and sizzle. Literally working from their garage, the tiny Apple team created the launching pad for a technological revolution—the Apple II, the first personal computer worthy of the name.

While Woz completed the functional prototype, Jobs focused on design, marketing, and financing. Jobs demanded that the Apple II’s exterior case look like an integrated KLH stereo—a popular offering at the time among young adults. No detail was too trivial. To reduce ambient noise, he decided to kill the standard cooling fan and “conned”20 Rod Holt from Atari into designing a brand-new kind of power supply by promising him $200 a day, an amount the cash-strapped Jobs was in no position to pay at the time.

His relentless quest for the perfect new product even penetrated into the innards of his creation that no user would ever see—almost a metaphor for his own personal internal ethic of minimalist utility. In one instance he decreed that every solder connection be done in a precise, attractive straight line that gave the Apple II’s circuit board a surprisingly sharp aesthetic. It’s an extraordinary perspective given the nascent state of the industry born from raw silicon components and homemade kits.

Such singular focus and intelligence would cause him problems later in his career. Like Howard Roark, Jobs’s uncompromising demands—while right and true to his own individualist vision—made him seem arrogant and inflexible to the more collectively minded around him. According to biographer Pilar Quezzaire, “Jobs’ fiery personality and extreme self-confidence tends to leave employees and colleagues fearful as well as awe-struck.”21

On the business side, he persuaded Frank Burge from ad agency giant Regis McKenna to take Apple’s account by badgering him three or four times a day after repeated rejections—until the major executive bent to the will of the 20-something entrepreneur. Then Jobs recruited retired Intel executive Mike Markkula as chairman to provide additional financing and business experience, after convincing him they could change the world by putting computers into homes and small businesses. In turn, Markkula brought in Mike “Scotty” Scott, an executive at National Semiconductor, as Apple’s president.

To introduce the Apple II, Markkula spent $5,000 for a flashy booth and front-door position at the West Coast Computer Faire in 1977. Jobs’s custom plastic cases arrived at the last minute with cosmetic flaws and no time to reship, so he put together a crew to sand, scrape, and paint them the night before. On opening day, people crowded the booth unable to believe these small, sleek boxes could be responsible for the color images displayed on the big TV monitor. Jobs had to routinely throw back the booth draping to prove there was no secret mainframe hidden from view. Curious engineers asked to pop the hood and were amazed by Woz’s cutting-edge design that fit an unprecedented 62 chips on a compact motherboard that looked as sleek as its function. Soon they had 300 orders.

The next few years were tough on Jobs. The business grew under the professional leadership he himself had recruited, but despite his founder’s status, Markkula and Scott marginalized the youthful Jobs, leaving him with little true authority and the belittling title of vice president of research and development. Longing for a project he could put his imprint on, he envisioned a brand-new computing paradigm, having been inspired by a trip to the secretive Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC).

In exchange for allowing Xerox to buy 100,000 shares of pre–initial public offering (IPO) Apple, Xerox agreed to open the kimono on some advanced computer research it was conducting. What Jobs saw at PARC changed the face and culture of computing forever. Among the developments were a fully functional prototype computer called the Xerox Star sporting a graphical user interface (GUI), with overlapping “windows,” pictorial icons representing programs or commands, a pointing device for user input—now known as the familiar “mouse”—and a fast, silent laser printer that beautifully rendered on paper what you could see on the screen. While these innovations are commonplace today, in the late 1970s era of command-line prompts, green-screen monitors, complicated keyboard-based hexadecimal machine code inputs, and rattling impact printers, PARC’s technology was breathtaking. Yet within the bureaucracy of Xerox, precisely nothing was being done to develop its commercial potential. Jobs immediately grasped the possibilities and set to work revolutionizing the personal computer he himself had just invented a few scant years earlier.

The idea was to include every advanced technology and feature he could think of in a compact form that would be so revolutionary it “would put a dent in the universe.”22 Jobs’s brainchild would be known as Lisa, named after the daughter he fathered with a past girlfriend. But the professional computer scientists now filling the ranks at Apple balked at his hubris. Markkula and Scott would soon reorganize the company, pulling Jobs from the Lisa project and handing it over to a cabal of uninspired engineers under even less inspiring leadership. As consolation, Jobs would be given the strictly symbolic title of chairman of the board. Eventually, the Lisa would become an overpriced disaster—the product of design by a mediocre collective, not Jobs’s individual vision. It would leave Jobs with an even greater appreciation of what he did best: inspiring—and infuriating—small groups of extraordinarily talented individuals to create astoundingly original products under seemingly impossible and uncompromising terms.

Despite Lisa’s false start, by 1980 Apple Computer was on a tear. The biggest kid on the PC block, Apple had sold over 250,000 personal computers since 1977. With over 1,000 employees and facilities across the globe, it continued moving nearly 20,000 computers per month and would rack up $300 million in annual sales that fiscal year alone. At a typical hardware cost of $2,500 (or over $6,000 in today’s dollars) Apple computers cost twice as much as competitive offerings from Commodore and Tandy, yet eclipsed their sales volume handily (IBM hadn’t even entered the PC market yet). It is a testament to Jobs’s insistence on usability and sleek design that Apple had tens of thousands of users willingly paying for a premium brand.23 It was a precursor to the business model Apple would employ with the iPod, iPhone, and iPad.

Apple Computer Corporation went public on December 12, 1980, selling 5 million shares at $22 each, raising $110 million for the company. The offering was oversubscribed even though it wasn’t available in 20 states, including the normally IPO-friendly Massachusetts, because the stock was deemed “too risky” by government regulators.24 At the end of the first trading day, Apple had a market capitalization of over $1.5 billion. The 25-year-old Jobs held over $200 million.

In early 1981, still sidelined, Steve was casting about for a new idea when he remembered an experimental project envisioned by a computer scientist named Jef Raskin who was working on the fringes of Apple. His concept was to make an all-in-one self-contained computer that presented itself to the customer as an appliance, like a toaster. No add-on components would be required, and the machine would instantly boot up without any arcane commands or cumbersome software to load. He dubbed it the Macintosh.

Jobs had originally blackballed Raskin’s idea back when Jobs was still leading the Lisa team, viewing it as a conflict with his own project. Now, a project to call his own that would compete with and beat the Lisa was just what he was looking for. According to biographers Jeffrey Young and William Simon,

Steve no longer had to subjugate his outlaw spirit to the corporate process, rewarded with little but his unceremonious booting off the Lisa project; here was the kind of dedication he understood, the kind he loved. These were crusaders like himself who thrived on the impossible. Steve would inspire this little-noticed team in a corner of a forgotten building. He would show them all—Scotty, Markkula, the whole company, the entire world—that he could lead them to produce a remarkable computer. . . . He set off with guns blazing to make the Macintosh the world’s next groundbreaking computer.25

It was an internal struggle to reassert himself at Apple, but Jobs also saw it as a race to beat IBM and preserve a place for creative innovation in PCs in the face of an oncoming corporate behemoth. He drove his team with high demands, but also with whimsy and irreverence, carving out their own separate office space for the best talent, instilling a desire for hard work and long hours that would establish each member as part of an elite club that he often referred to as his “pirates.”

By this time, Scott—whom Jobs had recruited as Apple’s president—had worn out his welcome and then some. His abrasive personality did him no favors among the creative technical teams, and after ordering a brutal series of layoffs in an event known as “Black Wednesday,” his days at Apple were numbered. Markkula returned from vacation and asked for Scott’s resignation. The board spent months searching for a replacement.

It was not to be Jobs. He felt he was capable of running the company, but he was the only one who thought so. If the board wouldn’t let him run the company, at least he could find someone he could work with. John Sculley of PepsiCo seemed like an inspired choice. While considered a technological lightweight, he knew about running a consumer products company and could help support Apple Computer’s efforts to position itself as a name-brand product instead of a hobbyist’s box of components. Jobs met with Sculley in New York in March 1983 and posed the now legendary query: “Are you going to sell sugar water the rest of your life when you could be doing something really important?” Sculley joined Apple as CEO shortly thereafter.

While Jobs and his pirates were feverishly working to make their Macintosh user-friendly and aesthetically pleasing, Bill Gates and his brilliant but pedantic programmers at Microsoft, working on IBM’s competing operating system, concentrated on power and technical fine points. According to Sculley, “The legendary statement about Microsoft, which is mostly true, is that they get it right the third time. Microsoft’s philosophy is to get it out there and fix it later. Steve would never do that. He doesn’t get anything out there until it is perfected.”26 And perfected it was, or as near as Jobs could make it, after a series of delays from the initial time line.

To promote the Macintosh launch, Jobs commissioned film director Ridley Scott of Alien and Blade Runner fame to create an ad to run during the 1984 Super Bowl. It would be a million-dollar bet, significant if not unprecedented in the early 1980s—and it would prove to be one of the most famous and enduring TV ads in history. It depicted a stark Orwellian future filled with drab marching clones brainwashed by a black-and-white projection on a vast screen of “Big Brother” espousing a collectivist ideology. A blonde female athlete bursts through the crowd in vibrant color chased by a jackbooted Gestapo squad, only to hurl a flying hammer into the screen, shattering the collectivist image in a burst of individualist light. The tagline: “On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’”

The ad was brilliant. It was unlike anything anyone had seen before. And the Apple board hated it. It was as if Jobs had become Howard Roark himself in the scene from The Fountainhead in which he sits in front of the architectural committee of a bank discussing his design for its new headquarters building. It was just too “stark,” too “radical.” It wouldn’t “please the public.” In Jobs’s case, perhaps the board objected to the commercial precisely for what Ayn Rand would have loved about it: its portrayal of the victory of the individual versus the collective. Indeed, for Jobs this is what the personal computer was all about: the empowerment of the individual user.

The board ordered Jobs to sell back the advertising time, but it was too late. The ad ran only once, on January 22, 1984, but it was so unique, so stunningly original—just so cool—that stations across the country replayed it on the evening news, generating the first instance of the “viral” buzz, as well as the Super Bowl ad frenzy now commonly sought by advertisers. It was a fundamental innovation in the way mass marketing was done—not just for computers, but for everything—and it was Jobs who did it.

Macintosh sales were brisk in early 1984, but slowed down later in the year. By the time of its first anniversary in 1985, 275,000 Macs had been purchased—an impressive number, but still short of Jobs’s 500,000 forecast, and not enough to meet critical revenue goals. Part of the problem was that there were few third-party software programs available for the machine, and the ones that did exist had difficulty running on the Mac’s scant 128K of memory. Jobs’s vision, it seems, was ahead of the technological capabilities of the day.

Internal friction erupted within the company as financial stresses increased. Jobs was chairman of the board above CEO Sculley, while simultaneously working under him as head of the Macintosh division. It was a dysfunctional structure that a weak-kneed, conformist board would ignore until it was too late.

For his part, Jobs felt he could run the company himself and, as its co-founder, railed against his powerful vision being overruled and stymied by a stodgy collectivist bureaucracy. In turn, Sculley came to liken Jobs to Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. In Odyssey, his memoir of this period, he called Jobs “a zealot, his vision so pure that he couldn’t accommodate that vision to the imperfections of the world.”27

“Apple was supposed to become a wonderful consumer products company,” Sculley wrote. “This was a lunatic plan. High tech could not be designed and sold as a consumer product.”28 As it would turn out, Sculley was dead wrong.

Soon an outright power struggle emerged, with various camps simultaneously trying to shift blame and secure their position. Marketing chief Mike Murray circulated a memo to the executive team under the heading “DO NOT CIRCULATE, COPY, OR SHARE,” lambasting Steve for “espousing vision . . . at the clear expense of corporate survival.” Then in April, early investor and taciturn board member Arthur Rock sensed weakness and instigated a boardroom coup. Citing poor financial performance, Rock, who was more interested in funding social causes than Jobs’s brand of youthful dreams, challenged CEO Sculley to take decisive action. Feeling the noose around his own neck, Sculley sacrificed Jobs, removing him as head of the Macintosh division. The ensuing reorganization consolidated operations and left Jobs conspicuously absent from the organization chart. Sculley refused to acknowledge Jobs or even mention his name at the company-wide meeting to announce the new structure.

In September 1985, relieved of his daily responsibilities at Apple, Jobs tendered his resignation from the board. “The company’s recent reorganization left me with no work to do and no access even to regular management reports,” he wrote. “I am but 30 and want still to contribute and achieve.”29 In the same spirit as Rand’s greatest hero, John Galt, Jobs led a strike of the mind against Apple, hiring away some of its top talent to join him in a new independent venture. The board was furious and contemplated legal action in a petty attempt at restricting Jobs from competing with them at their own game. But Jobs’s mind would not be enslaved.

The press at the time presaged the coming decade of Apple’s struggles without Jobs and the brains that Jobs took with him when he left. A New York Times article in September 1985 predicted, “Apple, while having a solid management, still might miss Mr. Jobs. The company is weak in top engineering talent to guide product development. Moreover, more traditional managers like Mr. Sculley have often proved no more adept at running technology companies than the original entrepreneurs. Some analysts and former employees are worried that Apple is losing its spark and becoming stodgy, a process some refer to as ‘Scullification.’” They would prove to be dead right.

The ensuing years for Jobs turned out to be like Roark’s time designing mere gas stations instead of great skyscrapers, and ultimately working as a day laborer in a granite quarry. Kept by the world from the work he loved, Jobs would live true to his own integrity, designing and building in areas where he saw value for his own sake. When they were ready to call him back on his own terms, he would be ready.

Jobs formed a company called NeXT to create the next-generation personal computer packed with all of the latest ideas that he felt restricted from pursuing within Apple’s corporate confines. The device would use a powerful new Motorola chip, optical magnetic drives, a new breed of operating system called NeXTSTEP, and brilliant anti-aliased graphics, all housed in a 1 × 1 × 1-foot magnesium cube. He would target the higher education market with a computer powerful enough to run complex genetic research simulations while being simple enough for students to use in their dorm rooms.

With investments from Ross Perot and Japan’s Canon, Jobs built out a lavish corporate headquarters, spending $1 million on a floating staircase designed by I. M. Pei and $100,000 for a logo from legendary graphic designer Paul Rand. He created a futuristic manufacturing facility filled with laser-guided robotics that outnumbered humans two to one.30 But ultimately, the amazing design and operating system for the cube failed to overcome its hefty $10,000 price tag. While the computer did sell an estimated 50,000 units over four years,31 it was a disappointing showing in an industry moving tens of millions of computers per year. Without the deep pockets of a public company and brand reputation in an increasingly mature market, NeXT had an uphill battle.

Meanwhile, always on the lookout for new ideas, he made a trip north to see George Lucas and his Lucasfilm-ILM operation in San Rafael, California. What he saw there stunned him. Here was a group of the most talented graphic artists in the world quietly creating groundbreaking digital images and film sequences on some of the most sophisticated computer systems he’d ever seen. “It was a Xerox PARC moment,” according to biographers.32

Even more stunning was that Lucas, in need of immediate liquidity in the aftermath of his recent divorce, was eager to sell the entire operation lock, stock, and barrel for $30 million. Jobs was salivating, but his shrewd negotiating sense detected blood in the water, so he decided to wait Lucas out in hopes of a better deal. With such a unique asset, finding a willing suitor on short notice would be next to impossible. Jobs ended up buying the company for $10 million in 1986 and christened it Pixar.

Hearkening back to the early days of Apple, the company initially focused on selling hardware dubbed the Pixar Image Computer. The device was powerful, but found limited application mostly for complex image analysis in government intelligence services and medical markets. Disney Studios was also a customer. Though Uncle Walt’s team still prided itself on traditional hand-drawn animation, it was slowly adopting computers to automate certain tedious coloring processes. It was the beginning of a relationship that would prove fortuitous for both companies in the coming years.

With Pixar in financial trouble from slack hardware sales, former Disney animator and then Pixar executive producer John Lasseter began creating computer-animated commercials for outside companies, generating a trickle of much-needed revenue. In 1988, Pixar also began licensing a software product it had developed earlier, called RenderMan, which allowed animators to quickly and easily refine complex 3-D scenes with appropriate shading and lighting. It remains the most widely used rendering standard in the industry today.

Advertising animation and software generated critical cash flow to keep Pixar on life support, but the company was still hemorrhaging $1 million per month. NeXT wasn’t faring any better, and between the two Jobs spent tens of millions from his own pocket just to keep the companies alive. A man who was once one of the wealthiest people in the country now saw his fortune dwindling to perilously low levels.

Despite heart-wrenching cutbacks at Pixar and a bottom-line temptation to close down the animation group altogether, Jobs personally funded the cash outlay to develop a short film to be shown at the SIGGRAPH computer graphics conference in 1988. It was a critical decision that would change the face of moviemaking forever. It was also the kind of move that a play-it-safe bureaucratic CEO would never have made. But an individualist like Jobs could make it, just because he thought the animated short called Tin Toy was so cool. It was indeed cool. It would go on to win an Oscar and eventually become the basis for the blockbuster Disney collaboration Toy Story.

The late 1980s and early 1990s would spark an epiphany of sorts for Jobs, with curious parallels between NeXT and Pixar. Jobs began to realize that the hardware he had focused so much effort on since the early days at Apple would eventually become a “sedimentary layer”33 in the evolution of technology upon which others would build. His metamorphosis was to grasp a paradigm that transcended hardware and software. He began to see how technology unlocked a unique experience even more lasting than the computers or software used to create them. Chips and programs lived short lives in the relentless march of technological progress. Music and stories endured for generations.

In his transition toward this experiential model, Jobs sold the Pixar Image Computer hardware division to Vicom systems in 199034 and retained fewer than 100 employees to focus on animation. Then in 1993, he withdrew NeXT from the hardware businesses and renamed the company NeXT Software to continue meeting a growing demand for their innovative object-oriented NeXTSTEP operating system.

NeXT hardware was never a commercial success, but it was a notable influence in the history and lore of computing. Tim Berners-Lee created the first Web browser in 1990 on a NeXT machine, claiming, “I could do in a couple of months what would take more like a year on other platforms, because on the NeXT, a lot of it was done for me already. There was an application builder to make all the menus as quickly as you could dream them up.”35 John Carmack of id Software used a NeXT machine to develop the video game Doom—the landmark “first-person shooter.”36 It was the object-oriented NeXTSTEP operating system that would prove to be the crown jewel in Jobs’s kingdom, and his passport back to Apple.

Meanwhile, Pixar was struggling to stay afloat, but saw a potential lifeline through an increasing dialogue with Disney. In an attempt to break its string of mediocre films, for the first time ever Disney was thinking about using an outside company to produce a computer-animated feature, but was meeting internal resistance. In their fight against obsolescence, Disney’s old-school pen-and-inksters claimed computer animation couldn’t possibly live up to Disney’s standard of quality. But some early—and secret—computer animation collaboration with Pixar on such classics as Beauty and the Beast built a level of trust among the Disney executives that it could indeed be done.

Although in 1991 his company was running out of oxygen, Jobs negotiated with Disney a deal for not one, but three feature movies. Disney would pay for production and give a slice of the net from the films back to Pixar. In turn, Pixar would retain all rights to technology and its secret creative sauce. And in a negotiating flourish that was pure Jobs—and must have been very difficult for Disney to swallow—the agreement permitted Pixar’s animated logo to be displayed with equal prominence alongside Disney’s famous image of Cinderella’s castle at the beginning of each film.

Based on the Tin Toy short, Disney approved the script for Toy Story in mid-1993, clearing the way for production. But months later, Disney’s head of feature films, Jeffrey Katzenberg, wasn’t satisfied with the character development. On November 17, Pixar received formal notice that Disney was shutting down production.

The dawn of 1994 brought dark days for Jobs. Exactly a decade after the glittering launch of the Macintosh, he was at his personal and professional nadir. He had fallen from grace at Apple and been trounced in the press over problems at NeXT, and now his personal investment in Pixar was sinking beneath the waves while Disney sailed off on the horizon. Jobs was depressed and withdrawn. It seemed to him that his previous success as a boy wonder might just have been a fluke.

But he refused to give up or give in. Learning the ways of fickle Hollywood executives, he shrugged off Disney’s blow and picked himself off the mat to fight again. After challenging his writers to recraft the script, he repitched it to Disney. Katzenberg liked the approach and unfroze the project. Then came a moment when Jobs wondered if he was a victor or a fool. With all the resources poured into the film, he figured it would need to gross $100 million at the box office just for Pixar to break even—more than any other Disney feature in recent history. At one point during the ordeal he confided, “If I knew in 1986 how much it was going to cost to keep Pixar going, I doubt if I would have bought the company.”

Toy Story opened in November 1995 to rave reviews and a weekend box office take of $29 million—nearly equal to the full cost of production. The movie would eventually gross over $350 million worldwide with an additional $100 million in video sales. Sensing good advance buzz, Jobs had timed Pixar’s IPO to coincide with the movie’s release, going public on November 29, 1995, at $22. Shares quickly shot up to $44.50 during the first hour in trading. Jobs had invested a total of $60 million in the company and nurtured it for nine years. He was suddenly worth over $1 billion.37

Unbelievably, some employees took him to task for being greedy and not allocating more of his 80 percent share in the firm to his workers. At least one former executive, cut from the cloth of Ayn Rand herself, disagreed. “We live in a world where everyone says, ‘It’s unfair—somebody got more than me.’”38 Employees negotiated their stock options up front and were fortunate that the company even survived through lean years on the strength of Jobs’s checkbook. “Can you really blame Steve if he didn’t feel like giving them more stock than they had agreed on when they were hired?”39 Like Roark, Jobs neither gives nor asks for charity. As Roark puts it, “I am not an altruist. I do not contribute gifts of this nature.”

With future films A Bug’s Life, Toy Story 2 and 3, Monsters Inc., and many others, Pixar would rack up billions in earnings and earn the title of the most successful movie studio of all time. More important, Jobs had transformed an entire industry through his audacity and stalwart belief—both in the technologies he thought were cool and in himself. Computers would enter the mainstream of visual entertainment as a vehicle to tell enduring stories. And Jobs wasn’t done yet.

By 1995, Apple was on the ropes and struggling to stay standing. Customers were flocking to the latest generation of improved Microsoft Windows software and it looked like Apple might become a footnote in the annals of computer history. Sculley had been forced out in 1993 after Apple’s market share shriveled from 20 percent to a measly 8 percent under his watch. Turnaround expert Gil Amelio was installed to right the ship. He recognized that cost cutting would go only so far and began to push for a new operating system to first defend and then rebuild Apple’s market share. Increasingly convinced that the foundering in-house team was incapable of developing a solution in time, he cast about for a third-party alternative.

After analyzing the field of players, including several conversations with Bill Gates at Microsoft, Amelio decided that NeXTSTEP might be his salvation and began negotiating with a surprised but amenable Jobs on buying his company outright. Apple eventually paid $325 million in cash to the investors and 1.5 million shares of Apple stock, which went to Steve Jobs.40 Steve was also retained as a strategic adviser to Apple. NeXTSTEP would become the basis for the Mac OS X operating system and the company’s path back to profitability. But it was too little, too late for Amelio.

In mid-1997, Apple’s market share had fallen to 3 percent and the company reported a quarterly loss of $708 million. Amelio was ousted and Jobs was installed as interim president and CEO. He would work for the princely salary of $1. According to long-gone CEO Sculley, “I’m actually convinced that if Steve hadn’t come back when he did—if they had waited another six months—Apple would have been history. It would have been gone, absolutely gone.”41

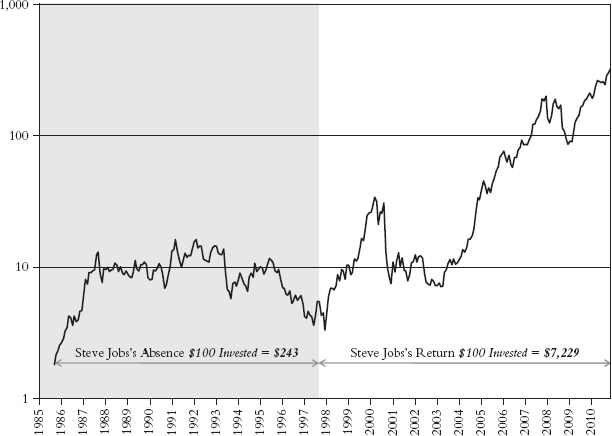

Apple’s stock price would seem to agree with Sculley—as we show in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Apple (AAPL) Stock Price

Back at Apple, Jobs quickly focused on revitalizing the business. He killed the foundering Apple Newton, a clunky handheld device that was widely lampooned, including a hilarious sequence in the popular comic Doonesbury.

In August 1998, Jobs introduced the iMac, an all-in-one unit encased in a translucent turquoise plastic shell harkening back to the days of the original Macintosh. Critics called it technically unimpressive and predicted it would be hampered by its overreliance on the universal serial bus (USB) for connectivity to peripherals. Once again, the traditionalist critics were wrong. While a nascent technology at the time, USB would become truly universal, allowing standardized connectivity of keyboards, mouses, printers, and portable memory across PCs and Macs alike. The look of the iMac itself would become a design icon of the late 1990s.

At $1,299 a pop, the iMac received over 150,000 preorders and went on to sell 278,000 units in the following six weeks.42 Strong sales were reported for both first-time computer buyers and those switching from a Windows-based PC. In October, Jobs reported the first profitable fiscal year since 1995. As one Wall Street analyst remarked, “Steve pulled the rabbit out of the hat over the past year. Apple was in disarray. It was at the gate of extinction. Now we have a company turnaround.” The results would catapult Apple back into the mainstream computer market from nearly perishing roadside as an also-ran.

With the company stabilized and on the road to recovery, some CEOs might rest on their laurels and collect a fat bonus. But not Steve Jobs. He doesn’t see himself so much as a business executive as an artist always taking new creative risks. In a Fortune interview he explained, “If you look at the artists, if they get really good, it always occurs to them at some point that they can do this one thing for the rest of their lives, and they can be really successful to the outside world but not really be successful to themselves. That’s the moment that an artist really decides who he or she is. If they keep on risking failure, they’re still artists. Dylan and Picasso were always risking failure.”43

By the end of the decade, music companies were struggling to confront a changing technological landscape. Clinging to old-school models of physical distribution channels, they were helpless in the face of a burgeoning network of Internet connectivity. In the past, music buyers might dub a copy or two of their favorite songs to give to friends. Now the same music buyers could “rip” a CD into a digital file and share it with a worldwide network of millions with the click of a mouse. Why buy a CD when you could get the music for free through file-sharing services like Napster?

For Jobs, music held a special place in his heart, along with respect for intellectual property. He could see the problems emerging in the music industry and was appalled at the spastic response by the record companies. On one hand, they attempted to crack down on criminal pirates—often a kid in a dorm room who was just enthusiastic about music and was listening to emerging artists. On the other hand, they offered restrictive subscription services on a pay-by-the-month model. Jobs saw a middle path and set out to change the landscape.

As he explained to Rolling Stone, he set up meetings with record executives. First, he made it clear that he respected the primacy of intellectual property rights—what individualist wouldn’t? “If copyright dies, if patents die, if the protection of intellectual property is eroded, then people will stop investing. That hurts everyone. People need to have the incentive so that if they invest and succeed, they can make a fair profit. But on another level entirely, it’s just wrong to steal. Or let’s put it this way: It is corrosive to one’s character to steal. We want to provide a legal alternative.”44

Next, he demolished their digital business model. “We told them the music subscription services they were pushing were going to fail. Music Net was gonna fail, Pressplay was gonna fail,” Jobs would say. “Here’s why: People don’t want to buy their music as a subscription. They bought 45s, then they bought LPs, they bought cassettes, they bought 8-tracks, then they bought CDs. They’re going to want to buy downloads. The subscription model of buying music is bankrupt. I think you could make available the Second Coming in a subscription model, and it might not be successful.”45

Finally, Jobs described the middle path. He would offer an Apple music store. It would be safe from viruses; it would be fast; and it would be high-quality, inexpensive, flexible, and, best of all, legal. In a way only Jobs’s mind could synthesize, he struck an elegant balance between artists’ rights and customer usability. Once you bought a song, you owned it. You could burn it onto a CD; you could play it directly from your computer or portable device. You could even share it with a few friends. But the embedded technology would prevent mass distribution and wide-scale pirating. At $0.99 per song, it was affordable—an impulse item—yet artists were compensated for their work. It was brilliant.

And in some ways it took a figure as big and trusted as Jobs to move the industry seized in paralysis as it faced the technological future. Only he had the clout, the appreciation, and the respect to pull an entire industry toward a visionary future. By the end of the decade, Apple iTunes would be selling over a quarter of all music in the United States. Jobs again had rescued and transformed a moribund industry—just because it was cool.

What does the future hold for Steve Jobs? His problems with his health are well-known, but as of this writing he’s been able to cheat death as brilliantly as he’s been able to overcome technology and business challenges throughout his life.

Someday death will come to him, as it must to all of us. What he’s built for the world will make him an immortal figure in the history of technology and business. But he’s immortal in another sense, in the way that all self-motivated and self-consistent people are—that they don’t die a little bit every day by compromising themselves, that during their lifetimes they truly live.

What a fellow artist said of Howard Roark in The Fountainhead might have been said of Steve Jobs: “I often think he’s the only one of us to achieve immortality. I don’t mean in the sense of fame, and I don’t mean he won’t die someday. But he’s living it. I think he is what the conception really means.”