Chapter 8

The Sellout

Alan Greenspan as Robert Stadler, the libertarian who became an economic czar

“Of any one person, of any single guilt for the evil which is now destroying the world—his was the heaviest guilt. He had the mind to know better. His was the only name of honor and achievement, used to sanction the rule of the looters. He was the man who delivered science into the service of the looters’ guns.”

—Atlas Shrugged

Who is Robert Stadler?

In Atlas Shrugged, Dr. Robert Stadler is a brilliant scientist who sells out to collectivism—and ends up destroying himself.

As a professor of physics at Patrick Henry University, he is mentor to John Galt and two of Atlas Shrugged’s other primary heroes, Francisco d’Anconia and Ragnar Danneskjöld. But in his single-minded quest to pursue pure science, he becomes head of the State Science Institute, a government-funded think tank.

Galt abandons his studies with Stadler the moment he endorses the Institute. Galt says, “He’s the man who sold his soul. We don’t intend to reclaim him.”

Throughout Atlas Shrugged, the power of the Institute and the prestige of Stadler’s name are used to exploit and expropriate the industrialists struggling to keep the economy afloat. Ultimately, scientific theories that Stadler thought were mere abstractions are used by the Institute to create a weapon of mass destruction designed to control the increasingly restive public. At the book’s climax, Stadler seizes control of the weapon and inadvertently detonates it, resulting both in widespread destruction of what’s left of America’s industrial infrastructure, and in Stadler’s own agonizing death.

Courtroom scenes figure prominently in two of Ayn Rand’s greatest novels, The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged. They are where great men and great ideas are publicly vindicated. It’s ironic that the most spectacularly successful of Rand’s inner circle, Alan Greenspan, widely hailed as the greatest central banker who ever lived, would be put on trial along with Rand’s ideas—and neither would be vindicated.

The trial was a hearing of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, convened in October 2008 to investigate the banking crisis that swept the world in the wake of Lehman Brothers’ collapse. The prosecutor was committee chair Henry Waxman, the crusading ultraliberal representative from Beverly Hills. Looking down at Greenspan from an elevated rostrum designed to intimidate witnesses, with his buckteeth, flaring nostrils, jug-handle ears, and bald head, Waxman looked like a cross between Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera and Mortimer Snerd.

Waxman pounded Greenspan with pointed questions about the apparent failure of the Federal Reserve under Greenspan’s tenure to regulate the banks that collapsed. This was a dangerous matter for Greenspan, for whom there had always been serious tension between the demands of his role as Fed chairman—the most powerful regulator in the world—and his history as an intimate of Ayn Rand, who was so opposed to business regulation that, in Atlas Shrugged, she describes a wise judge drafting a constitutional amendment to prohibit it outright.

The toughest moment for Greenspan was surely when Waxman said, “Dr. Greenspan, Paul Krugman, the Princeton professor of economics who just won a Nobel Prize”—and whom we met in Chapter 2, “The Mad Collectivist”—“wrote a column in 2006 as the subprime mortgage crisis started to emerge. He said, ‘If anyone is to blame for the current situation, it’s Mr. Greenspan. . . .’ So do you have any personal responsibility for the financial crisis?”1

Looking up at Waxman from the witness table, his enormous, wet, soulful eyes peering through his trademark goggles, looking for all the world like an aging Woody Allen miscast in some great tragic drama, Greenspan said a lot of words but didn’t exactly come out and answer “yes.” No surprise that. He’d become famous over nearly two decades as Fed chair for his inscrutable oracular comments.

So Waxman just kept at him: “You feel that your ideology pushed you to make decisions that you wish you had not made?” “Do you think that was a mistake on your part?” “My question for you is simple—were you wrong?”

But it didn’t matter, really, because Greenspan had already confessed before the hearing even began. In a column for the Financial Times seven months earlier, he had written, “Those of us who look to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholder equity have to be in a state of shocked disbelief.”2

To Waxman, he added, “I found a flaw in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works. . . . That’s precisely the reason I was shocked, because I had been going for 40 years or more with very considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well.”3

For Greenspan, just as for Rand, self-interest was indeed “the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works,” or at least how it ought to work. For Rand, it was embodied in her controversial slogan, “the virtue of selfishness.” Greenspan said it decades ago in his own words, in 1963, in an essay for Rand’s Objectivist Newsletter:4

It is precisely the “greed” of the businessman, or, more appropriately, his profit-seeking, which is the unexcelled protector of the consumer.

For Greenspan to repudiate self-interest is tantamount to repudiating Rand—after having been her close friend, colleague, and partner in arms for 22 years, right up until the day she died on Greenspan’s birthday in 1982.

To some it seemed that he had repudiated her already, in 1975, when he became chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, betraying her vision of strictly limited government, joining the ranks of the bureaucrats, central planners, and regulators. In that same 1963 essay he had written:5

There is nothing to guarantee the superior judgment, knowledge, and integrity of an inspector or a bureaucrat—and the deadly consequences of trusting him with arbitrary power are obvious.

Those consequences became painfully obvious to Greenspan himself, after years at the very pinnacle of bureaucratic power as chairman of the Federal Reserve, blamed by Waxman and many others for failing to prevent—or perhaps even for causing—a world-historical global banking meltdown.

But Rand didn’t feel betrayed when Greenspan went to the White House in 1975. In fact, she went with him, as a photo of Greenspan being sworn in by President Gerald Ford at the White House attests (see Figure 8.1). The little lady with Ford’s arm around her is Greenspan’s mother, Rose. The little lady next to Greenspan is Ayn Rand.

Figure 8.1 Alan Greenspan Is Sworn In as Chairman of the Counsel of Economic Advisers, 1975. (Left to right) Rose Greenspan, President Gerald R. Ford, Alan Greenspan, Ayn Rand, Frank O’Connor

Source: Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum

So apparently Rand, said to be quick to excommunicate acolytes who deviated from her philosophy, didn’t object to Greenspan’s new role. In fact, she was proud—for Greenspan, and for herself. For the press, she described Greenspan as “my disciple,” and “my man in Washington.”6

So it’s difficult for us to say that Greenspan is a Randian villain (Rand didn’t think so herself), though it’s tempting simply because as Fed chair he became the most prominent and powerful regulator in the world. Perhaps in reality he was a Randian hero, a double agent, covertly promoting the ethic of self-interest and its political corollary, laissez-faire capitalism, from within the very center of government power.

If Alan Greenspan were a Randian villain, though, he would be Dr. Robert Stadler from Atlas Shrugged. Stadler was a great physicist, and one of the two mentors of Rand’s greatest hero, John Galt. He betrays Galt by doing just what Greenspan did: leaving the private sector and going to work for the government.

Galt calls Stadler “the man who sold his soul.” He says of him, and scientists like him who work for the government, that they “sell their intelligence into cynical servitude to force . . . they are the damned on this earth, theirs is the guilt beyond forgiveness.”

At the climax of Atlas Shrugged, Stadler’s scientific research is co-opted by the government to create a weapon of mass destruction designed to control the civilian population. Amid the chaos of the collapse of the American economy, the weapon is triggered accidentally with Stadler present, and he is killed.

Rand writes, “Nothing remained alive among the ruins—except, for some minutes longer, a huddle of torn flesh and screaming pain that had once been a great mind.”

Getting publicly humiliated by Henry Waxman is bad, but it’s not that bad.

Alan Greenspan first met Ayn Rand in 1952. He was introduced through his new bride Joan Mitchell, who was connected to Rand through their mutual friend Barbara Branden.

Greenspan attended a meeting of “The Collective,” the intellectual salon that gathered at Rand’s New York apartment to discuss philosophy, politics, and—most important—the ideas of Ayn Rand. Greenspan, who philosophically styled himself a logical positivist, postulated to Rand that there are no moral absolutes. Here’s how Greenspan recalls the ensuing debate in his memoirs:7

Ayn Rand pounced. “How can that be?” she asked.

“Because to be truly rational, you can’t hold a position without significant empirical evidence,” I explained.

“How can that be,” she repeated. “Don’t you exist?”

“I . . . can’t be sure,” I admitted.

“Would you be willing to say you don’t exist?”

“I might . . .”

“And by the way, who exactly is making that statement?”

Checkmate! For the young Greenspan, this kind of intellectual jousting was extremely exciting. But at first Rand wasn’t sure about Greenspan. She nicknamed him “the undertaker,” because of his dark suits and somber demeanor. She asked her protégé Nathaniel Branden, the husband of Joan Mitchell’s friend, “How can you stand talking to him? . . . A logical positivist? I’m not even certain it’s moral to deal with him at all.”8

Months later, after relentlessly chipping away at Greenspan’s logical positivism, Branden convinced Greenspan that he did, indeed, exist. He told Rand, “Guess who exists. . . . You’ll have to stop calling Alan ‘the undertaker’ now.”9

Branden and his wife Barbara took it upon themselves to see to Greenspan’s “conversion” to Rand’s philosophy. The first step in the conversion would prove to be a fateful one. One day Barbara reported to Branden, “Guess what. I got him to admit that banks should be operated entirely privately. . . . I sold him on the merits of a completely unregulated banking system.”10

Greenspan became a regular member of Rand’s salon, and was granted the privilege of reading Atlas Shrugged right as it came off of Rand’s typewriter. He was enthralled, finding Rand’s arguments “radiantly exact.”11

The Collective was in some ways a difficult group, full of interpersonal drama, with all members subject from time to time to harsh judgment by Rand for any perceived infraction of her philosophy. Greenspan came in for his share of criticism. Observing Greenspan’s relentless networking (which would one day serve him so well in Washington), she asked, “Do you think Alan might basically be a social climber?”12 She was skeptical of his involvement in the business world, once saying “A.G. is too ‘worldly,’ too impressed by success. The trouble with A.G. is, he thinks Henry Luce is important.”13

But Greenspan had a special status in Rand’s salon. One member recalls, “He kept somewhat aloof from everybody. He was older and smarter.”14 Another says Greenspan was Rand’s “special pet.”15 Contradicting her worries about his being too “worldly,” Rand herself said, “What I like about A.G. is basically that he has his feet on the ground. I love his love for life on earth.”16

After Atlas Shrugged was published, Ayn Rand became a full-fledged literary celebrity. Branden franchised Rand and her ideas into a lecture series and a newsletter, and Greenspan participated in both. At what became known as the Nathaniel Branden Institute (NBI), Greenspan taught a course called “The Economics of a Free Society.”17 He contributed to The Objectivist Newsletter, and its successor publication, The Objectivist, on topics such as business regulation, antitrust, and the gold standard. Some of these writings were eventually republished in a series of anthologies designed to ride on the coattails of Rand’s literary popularity, alongside essays by Rand, Branden, and other members of The Collective.

At the same time, Greenspan was becoming a considerable business success. When he first met Rand he was working at the National Industrial Conference Board. Bond trader William Townsend invited Greenspan to join him in forming an independent economics consulting firm. According to Branden, Greenspan hesitated to take the plunge. Branden urged him on, saying, “Take the leap. You can do it. . . . You just don’t appreciate how good you are.” Townsend Greenspan & Company hit the big time quickly, signing up a glittering constellation of Fortune 500 companies as clients. Several years on, Townsend died, leaving Greenspan in control of the company, and a wealthy man. Again according to Branden, Greenspan later thanked him, saying, “You believed in me.”18 For all that, Greenspan mentions Branden only once in his autobiography, and then only in passing.19

Greenspan’s involvement in politics began as a spectator in the 1950s, as he watched Arthur Burns, his faculty adviser in the PhD program at Columbia University, become chair of the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) under President Eisenhower. Rand was suspicious of Greenspan’s relationship with Burns. She loathed Eisenhower, seeing him as what we would now call a RINO—a Republican in Name Only.20

The path of Burns’s career in many ways eerily presages Greenspan’s, starting with the CEA and ending with the chairmanship of the Fed. It was also a cautionary tale for Greenspan. In his academic career Burns was a fierce defender of free markets, but when he joined government he seemed to become a Keynesian—following the doctrine of John Maynard Keynes, the British economist—advocating government stimulus and government control. Perhaps it was a pragmatic compromise, accepting the world as it is and sticking up for free markets to the extent possible. But as Fed chief, Burns is widely regarded as having caved in to political pressures from President Nixon, overly loosening monetary policy, and unleashing the catastrophic inflation of the mid-1970s and early 1980s.

Accounts differ as to exactly how Greenspan’s personal participation in politics began. Some biographers attribute his joining Richard M. Nixon’s campaign for the presidency in 1967 to a chance meeting with Leonard Garment, an old chum of Greenspan’s from his youthful days as a jazz musician, who would several years later become infamous as Nixon’s lawyer during the Watergate scandal.21 Greenspan himself says it started through his friendship with Martin Anderson, a Columbia economics professor whom he had met at an NBI lecture, who at the time was the Nixon campaign’s chief domestic policy adviser.22 Anderson had become a friend of Ayn Rand—he even contributed a book review to an edition of The Objectivist Newsletter—but he was never a member of The Collective’s inner sanctum.

Greenspan was impressed by Nixon’s mind, writing that “he and Bill Clinton were by far the smartest presidents I’ve worked with.”23 But he saw Nixon’s darker side, too: the bigotry, the paranoia, the stream of expletives that “would have made Tony Soprano blush.”24 So Greenspan chose not to accept an offer of a full-time position in the Nixon administration after the election. Smart choice. Not only did he mostly avoid having his reputation damaged by the Watergate scandal, but he also avoided association with a sequence of Nixon’s economic policy decisions that utterly flew in the face of free markets—most notorious, Nixon’s imposition of wage and price controls and the suspension of gold convertibility in 1971.

Then, in 1974, in the depths of a horrible inflationary recession, during an Arab oil embargo, and at the peak of the Watergate scandal, it all changed.

Greenspan got a call from Treasury Secretary William Simon asking him to become chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. He said no. He got another call from White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig. Again, no. The next call came from Greenspan’s old friend Arthur Burns, by then Fed chairman. Greenspan remembers, “My old mentor puffed on his pipe and played to my guilt.”25 This time it was yes. “But I told myself I’d take an apartment on a month-to-month lease, and figuratively, at least, keep my suitcase packed by the door.”26 The same day as Greenspan’s Senate confirmation hearing, Nixon announced his resignation.

So Greenspan became CEA chair under new president Gerald Ford, and was sworn in at the White House with his mother, Ayn Rand, and Rand’s husband, Frank O’Connor, in attendance (again, see Figure 8.1). Three weeks later, at Greenspan’s first CEA meeting, an economist present said that the cure for inflation “applies alike for Bolsheviks and devoted supporters of Ayn Rand, if there are any present.” Greenspan chimed in, “There’s at least one.”27

Rand didn’t damn Greenspan for going to Washington as John Galt damned Dr. Robert Stadler. She loved it. It was a difficult time in her life—she was beginning a long struggle with lung cancer—and as Barbara Branden put it, “Alan Greenspan’s success was one of Ayn’s rare sources of pleasure. . . . Ayn was delighted with his accomplishments, and delighted that he spoke openly and proudly of his admiration for her, for her work, for her philosophy.”28

Sometimes Ayn was outright thrilled with what Greenspan could do in government. While Nixon was still president, Greenspan participated in a commission that led to the abolition of the military draft, a goal near and dear to Rand’s libertarian heart. In this effort Greenspan worked closely with Milton Friedman, whom we’ll meet in Chapter 9, “The Economist of Liberty.”

Rand was over the moon, as it were, when Greenspan arranged for her to attend the blast-off of Apollo 11.29 But she bickered with him about heading a commission under President Reagan that ended up bolstering Social Security, a program Rand loathed. At a dinner in a New York club, she dressed him down so violently about it that people stopped and stared.30 But in the end, she said, “I am a philosopher, not an economist. . . . Alan doesn’t consult with me on these matters.”31

Greenspan got to be both philosopher and economist when he was appointed chairman of the Federal Reserve by President Ronald Reagan in August 1987.

Rand, who died in 1982, didn’t live to see it. But it was a moment of supreme irony, and not only because the libertarian Rand-ite Greenspan was assuming the role of the nation’s most powerful regulator. More, it was because the Fed is charged with providing the nation with arbitrary amounts of paper money, completely free from the strictures of the gold standard, or any other standard. Yet in a 1963 article for The Objectivist Newsletter, Greenspan had written that “gold and economic freedom are inseparable, that the gold standard is an instrument of laissez faire, and that each implies and requires the other.”32

In the same article, he wrote, “In the absence of the gold standard, there is no way to protect savings from confiscation through inflation.”33 Yet that’s just what Greenspan set out to do as Fed chair: to protect savings from inflation in the absence of a gold standard.

Or did he? If you look at the data the right way, it almost seems that Greenspan implemented a covert gold standard for the Fed during the first half of his long tenure as chair.

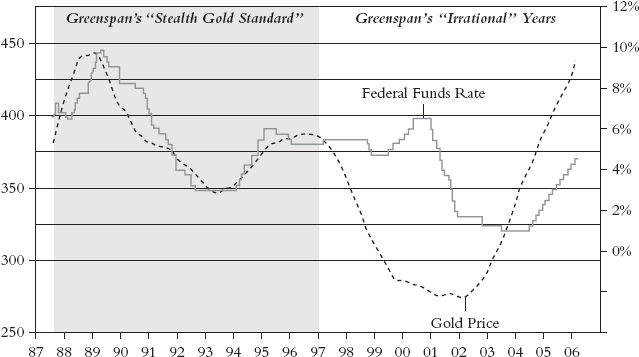

Consider Figure 8.2. It shows the federal funds rate—the short-term interest rate that is set by the Fed, its major instrument of policy—compared to the price of gold (dashed line). Do you notice anything strange? In the first half of the chart, up through most of 1996, every time the gold price rose, Greenspan raised the interest rate (light gray line). Every time the gold price fell, Greenspan lowered the interest rate. He didn’t respond to every little wiggle in the volatile gold price; that’s why we show the two-year moving-average price, a way to smooth out the short-term volatility and look at the durable price trend. But when gold made major moves, so did the interest rate.

Figure 8.2 Greenspan’s Stealth Gold Standard versus His Irrational Years. (Left axis) Gold Price, Two-Year Moving Average; (right axis) Federal Funds Rate

Source: Federal Reserve, Reuters, author’s calculations

Why would this be? The reason is simple. When the gold price measured in dollars rises, it’s telling the central bank that the value of the dollar is falling; that is, there is a risk of inflation. So raise interest rates to stop inflation. When the gold price measured in dollars falls, it’s telling the central bank that the value of the dollar is rising; that is, there is a risk of deflation. So lower interest rates to stop deflation. There’s no gold being physically bought, sold, stored, or moved in this setup. Yet gold is determining monetary policy. It is truly a gold standard, albeit not an overt one.

Why did it have to be only a stealth gold standard? Why not tell the world? Because while for the ordinary man on the street gold is still a superlative symbol of lasting value, in the rarefied air of academic economics it has become a symbol of outmoded and unsophisticated thinking. That epitome of economic snobbery John Maynard Keynes dubbed it “the barbarous relic,” and urged the world’s nations to abandon the gold standard in the Great Depression. The nickname stuck. While in reality every central bank in the world still hoards gold in its vaults, it’s not something respectable economists talk about as a part of modern monetary policy.

Dr. Robert Stadler put it simply enough in Atlas Shrugged: “If we want to accomplish anything, we have to deceive them into letting us accomplish it. Or force them.”

Greenspan’s stealth gold standard worked brilliantly for all the years in which it was applied. They were years of admirable economic stability. Yes, there was a recession in the middle of those years. But it was short and mild, and the stealth gold standard kept the Fed from overreacting to it. Certainly there were none of the bubbles during those years that would come to plague the U.S. economy afterward.

What of the stock market crash in October 1987? You can’t blame that on Greenspan or his stealth gold standard—it occurred just two months after he showed up at the Fed. On the contrary, here was another case in which Greenspan admirably didn’t overreact, perhaps thanks to the stealth gold standard. The conventional wisdom about the crash is that Greenspan miraculously rescued the world economy from its aftereffects. Some applaud Greenspan as a savior; others criticize him for putting in place after the crash the so-called Greenspan put—the implicit guarantee, the moral hazard, that supposedly led to the bubbles of the late 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s. But the reality is that Greenspan did essentially nothing after the crash. He issued a statement saying, “The Federal Reserve, consistent with its responsibilities as the nation’s central bank, affirmed its readiness to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system.”34 Just 29 little words. No bailouts. No nationalizations. No bazookas. No helicopter drops of money.

A central banker who does nothing—except watch the gold price. Maybe Greenspan was a Randian hero after all, a double agent for libertarianism in the very bastion of regulatory power.

Maybe it was true what Greenspan told U.S. Representative Ron Paul, the only libertarian member of Congress, when Paul asked him whether as Fed chair he would now add a disclaimer to his Objectivist Newsletter article on gold and economic freedom. Greenspan told Paul, “I reread this article recently—and I wouldn’t change a single word.”35

But then something changed in late 1996. For no known reason, Greenspan went off his stealth gold standard. As the price of gold fell, for the first time he didn’t lower interest rates. Instead, he raised them.

The stealth gold standard ended at exactly the same moment as Greenspan gave his famous speech warning of “irrational exuberance”—December 5, 1996. Speaking after two excellent years for the stock market, in which the Standard & Poor’s 500 had risen 37.6 percent in 1995 and then another 23.5 percent so far in 1996, Greenspan said,

[H]ow do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions . . . ? And how do we factor that assessment into monetary policy? . . . the sharp stock market break of 1987 had few negative consequences for the economy. But we should not underestimate or become complacent about the complexity of the interactions of asset markets and the economy.36

After that, Greenspan kept rates where he raised them in early 1997. Gold continued to fall, which under the stealth gold standard should have signaled to Greenspan that deflationary pressures were building, and that rates should be lowered to relieve them.

By 1998, those deflationary pressures started to weigh on the world’s most fragile debtors: the fast-growing Asian nations that had borrowed vast sums of dollars to build out their commodity-based economies. In the deflation Greenspan had triggered, the prices of commodities fell along with the price of gold, and at the same time debt service in dollars became intolerable. It was much like what happened to debtors around the world in the deflation of the Great Depression of the 1930s. The result was the so-called Asian flu, a contagion of currency devaluations and debt defaults that swept Asia from Thailand to Russia.

In the United States, the highly leveraged hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) got caught in the undertow of Asian and Russian defaults and devaluations. With all the top Wall Street firms exposed to LTCM, it was a systemic crisis. In response, Greenspan finally lowered interest rates—which his stealth gold standard would have had him do years before—and the pressure was relieved.

At the same time, the Fed organized a rescue of Long-Term Capital Management. We say “organized,” because that’s all the Fed did; it didn’t spend a dime of its own money bailing out LTCM. All it did was get all of LTCM’s shareholders in one room at the New York branch of the Federal Reserve, and convince them that the only way to save Wall Street was to have all of them kick in extra money to LTCM. It was the opposite of a bailout—it was a bail-in.

When the smoke cleared, Greenspan got credit for expertly averting a global crisis—yes, the same one he himself caused by going off his own stealth gold standard. Greenspan was featured on the cover of Time as the chairman of the Committee to Save the World, and people started calling him the maestro.

And the legend of the Greenspan put grew. Ask anyone on Wall Street how the LTCM crisis was resolved, and chances are good you’ll be told—wrongly—that the Greenspan Fed bailed it out.

With his laurels polished to the point of gleaming, Greenspan didn’t learn from his mistake. As irrational exuberance kicked into high gear and the dot-com stock market went hyperbolic at the end of the decade, Greenspan started raising rates again, taking them to new highs—even as gold kept falling.

He spoke of the “new economy,” yet he kept raising rates. It was as though he was now on a stealth Nasdaq standard instead of a stealth gold standard. But try as he might, he couldn’t burst the bubble. He says now, in frustration, that he had “raised the spectre of ‘irrational exuberance’ in 1996—only to watch the dot-com boom, after a one-day stumble, continue to inflate for four more years, unrestrained by a cumulative increase of 350 basis points in the federal funds rate from 1994 to 2000.”37

After the dot-com bubble burst in early 2000 (probably more from its own unsustainable silliness than anything Greenspan had done to burst it), the deflationary consequences of abandoning the stealth gold standard took on deadly new dimensions.

Coming out of the brief recession of 2001, inflation fell to the lowest levels in 40 years. It had dipped in mid-1998, and Greenspan had seen the consequences in Asia, Russia, and Wall Street. Now it was lower still. It was not negative—not actual outright deflation. But for Greenspan, knowing in his heart of hearts that he’d been erring versus his own stealth gold standard on the side of deflation, it was scary.

So Greenspan panicked. He went from keeping rates too high for too long to keeping rates too low for too long. He lowered interest rates to a mere 1 percent in mid-2003, a level not seen since the Depression. And he kept them there for an entire year, what the Fed kept announcing to the market, all the while, would be a “considerable period.” Then when the Fed finally started raising rates, it announced that its rate-hiking regime would be “measured.” Starting in mid-2004, the Fed began a series of regular, timid, 0.25 percent rate hikes at every Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting. Rates didn’t even get back up to a mere 3 percent until mid-2005.

Greenspan denies this,38 but many scholars now believe that keeping rates so low for so long was what triggered the boom in excessive mortgage lending in the United States and around the world—the boom that became a bubble, the bubble that became a bust, and the bust that became a global banking crisis and the Great Recession.

Among Greenspan’s sharpest critics on this is John Taylor, the Stanford University economics professor famed in monetary policy circles for positing the Taylor rule for setting interest rates. Taylor delivered his critique in the summer of 2007, just when the first tremors of the mortgage bust were beginning to be felt—when no one had any idea it would lead to a global crisis. At the Fed’s prestigious annual Jackson Hole research symposium, Taylor argued:

During the period from 2003 to 2006 the federal funds rate was well below what experience during the previous two decades of good economic macroeconomic performance . . . would have predicted. Policy rule guidelines showed this clearly. There have been other periods . . . where the federal funds rate veered off the typical policy rule responses . . . but this was the biggest deviation. . . .

With low money market rates, housing finance was very cheap and attractive—especially variable rate mortgages with the teasers that many lenders offered. Housing starts jumped to a 25 year high by the end of 2003 and remained high until the sharp decline began in early 2006. . . .

As the short term interest rate returned to normal levels, housing demand rapidly fell bringing down both construction and housing price inflation. Delinquency and foreclosure rates then rose sharply, ultimately leading to the meltdown in the subprime market. . . .39

While the Fed’s too-low rates fueled the mortgage and housing bubbles, the Fed as banking regulator did little to rein in abusive lending practices or excessively leveraged capital commitments by banks. It’s not like Greenspan didn’t know there were bad guys out there—and perhaps stupid guys, too. In the wake of Enron and other financial scandals in the early 2000s, he had spoken of “infectious greed”40—a phrase that became almost as canonical as “irrational exuberance.”

Why did corporate governance checks and balances that served us reasonably well in the past break down? . . . An infectious greed seemed to grip much of our business community. Our historical guardians of financial information were overwhelmed.

And it’s not like he couldn’t see housing prices get out of control. As Greenspan now protests, “I expressed my concerns before the Federal Open Market Committee that ‘. . . our extraordinary housing boom . . . financed by very large increases in mortgage debt—cannot continue indefinitely.’”41

Furthermore, it’s not like he didn’t know that the quasi-government lending agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were overleveraged and corrupt. He used his bully pulpit as Fed chair to attack them repeatedly and call for sweeping reform.

So when he says now that he is “shocked” by the failure of self-interest to rein in the banks all by itself, one thinks of the police captain in Casablanca who was “shocked—shocked!—to find that gambling is going on in here.” Yet the Greenspan Fed essentially did nothing about it.

Even if Greenspan were playing the Randian double-agent hero, trying to minimize the Fed’s regulatory footprint, there is one huge practical problem that such an idealistic strategy lethally overlooks. Greenspan forgot that the market expects the Fed to regulate the banking system, whether or not in Rand’s moral universe it ought to—especially the Greenspan Fed, in the hands of the maestro, the chairman of the Committee to Save the World, the man who always knows the right thing to do.

So why shouldn’t banks take highly leveraged off-balance-sheet risks based on mortgages that nobody in his or her right mind could have expected the borrower to repay? Greenspan’s not objecting—and he’s regulating this casino, isn’t he? Isn’t he?

So what’s a Randian hero double agent supposed to do? Well, as Dr. Robert Stadler asked in Atlas Shrugged, “But what can you do when you deal with people?”

Alan Greenspan politely refused our requests to be interviewed for this book, but he did agree to meet with us.

When we saw him in his Washington, D.C., office, we were struck by how terribly old and small and frail he is, this giant who bestrode the global economy for two decades. His large eyes still bloomed with intelligence at age 84, and his rapid-fire repartee revealed a mind still operating with enormous power. Yet when we grasped his hand to greet him, it seemed for a moment that his whole arm would come off at the shoulder.

It was more than just the physical exhaustion of age. There was also something about him that spoke of resignation, disappointment, even shame. And why not? What must it cost a man, after a record 18-year run as chairman of the Federal Reserve, seeing nearly two decades of unprecedented global growth, able to master every crisis along the way, celebrated as the greatest central banker of all time, and on the cover of Time as the chairman of the Committee to Save the World, to be blamed for the banking crisis that triggered the greatest global recession since the 1930s.

For Greenspan, it’s more than just having presided over the greatest global boom/bust cycle in history, having gone from adulation as the man who saved the world to vilification as the man who destroyed it. For Greenspan, this titanic fall from grace is all the more humiliating because it takes place squarely in the long shadow of Ayn Rand.

As Greenspan proudly told us when we met, he spent 30 years as a close friend of Rand, right up until the day she died in 1982. When we asked him whether in his confrontation with Henry Waxman he’d intended to recant his Randian beliefs in the supremacy of free markets, he told us absolutely not.

His despair, he told us, is not that his and Rand’s ideas turned out to be wrong. Rather, it’s that the world has abandoned them. Coming out of the Great Recession, he sees the United States having crossed a fateful threshold, a point of no return, at which we’ve taken on too great a government debt, and at the same time made too great a commitment to government control of the economy. He told us that we won’t recognize America 20 years from now, and that we won’t like what we see.

We asked him to inscribe our copy of Rand’s anthology Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal (a first edition already bearing Rand’s signature), in which is reprinted his article on gold and economic freedom. He told us that he thinks every idea in the book—his own and Rand’s—has stood the test of time.

We left feeling that Alan Greenspan is no villain. In his own way, he is indeed a hero—not a Randian hero, but rather a tragic one.