COME IN, PLEASE. ST P OUT O THE RAIN.

It had been raining for three straight days, and even the regular customers were staying away. On Thursday, Thomas had the idea of posting a sign on the doors of the museum. By Friday, several letters had blurred away, and the others were running toward the bottom of the page as though attempting a getaway. By Saturday afternoon, the note had turned to a sodden piece of pulp and, driven by the winds into the gutter, was carted away on the underside of a busy man’s leather-soled shoe.

Thomas was bored.

It was only April 20, and he had already read all the books Mr. Dumfrey had bought him for his birthday on April 2, including The Probability of Everything, which was nearly a thousand pages long, and A Short History of Math, which was even longer. So he spent the morning in the attic, playing DeathTrap, a game of his own invention. It was like chess, except that instead of using a checkerboard, it relied on the patterns of a threadbare Persian rug, and instead of pawns, bishops, and knights, the pieces were various things pilfered from the exhibits over the years: a baby kangaroo’s foot, which could only jump spaces; a dented Roman coin that could only be spun or flipped; an old shark’s jaw that didn’t move but conquered pieces that came too close by swallowing them; a scorpion tail that paralyzed other players so they lost a turn; an armadillo toe that could be used by any player, depending on who was in possession of the armadillo shell.

As usual, Thomas had no one to play with, so he had to do both sides.

He flipped the coin and sighed when it landed faceup. That meant he had to move the Egyptian scorpion tail back three swirls in the carpet.

“You should take the armadillo toe.”

Thomas looked up. Philippa, the mentalist, was sprawled across a daybed, watching him.

“What?” he asked. He and Philippa were both twelve, but her dark, almond-shaped eyes, her straight fringe of black bangs, and her sharply pointed chin made her appear much older.

Philippa sighed. “If you move the scorpion there”—she pointed—“you can take the armadillo. Tail takes toe, right?”

Thomas saw that she was right and felt annoyed. “I didn’t know you were playing,” he said. He had grown up with Philippa, but they had never been close.

Philippa shrugged and picked up her book—Mystics, Mind Readers, and Magic, which Thomas had also read and found exceedingly stupid—then rolled onto her back. When she wasn’t looking, Thomas swiped at the armadillo toe with the scorpion’s, sending it skittering off the rug.

He had won again. It would be more exciting if he hadn’t also lost.

He stood up, feeling restless. It was uncommonly quiet, the kind of day that made him feel lazy. Sam was sitting in one of several armchairs in the common area, his hair mostly concealing his face, as it had been ever since he’d discovered his first pimple. An issue of his favorite magazine, Pet World, was open in his lap.

Monsieur Cabillaud, the children’s tutor, was snoring. Having exhausted himself earlier that day in an argument with Philippa over who was to blame for the Thirty Years’ War, he had promptly taken a nap on the sofa with a textbook covering his tiny head.

Phoebe, the fat lady, had retreated to her bedroom. Smalls, the giant, was working on his latest poem and had spent the whole morning repeating “the swallows fly like shadows across the sky” and “like shadows the swallows fly across the sky” and “across the sky, like shadows, swallows fly” and shaking his head.

Danny, the dwarf, had gone next door for a drink. Hugo, the elephant man, was working on a crossword puzzle in the corner. Betty, the bearded lady, was carefully combing and braiding her beard. Goldini, the magician, had been puzzling all afternoon over a new trick but so far had succeeded only in vanishing three quarters somewhere under the sofa cushions. Rain lashed against the large windows, and the glass seemed to be slowly melting into liquid.

The radio was reporting news of another washed-out baseball game. Then the advertisements came on.

“Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls . . . step right up and don’t be shy! Down at Dumfrey’s Dime Museum is a world of wonder, of wondrous weirdness . . .”

“Turn it down, please,” Philippa said primly. “I’m reading.”

Just to spite her, Thomas stood and turned the radio up a few notches, even though he’d heard the ad a million times at least.

“. . . our brand-new exhibit, guaranteed to knock your socks off and spin your head around in its socket! New York’s only shrunken head! Straight from the Amazon! Delivered only yesterday!”

“Pippa’s right, Thomas,” Betty trilled in her sweet voice. “I’ve had enough talk of that silly head. Uglier than sin, if you ask me!” She swept her long brown beard over one shoulder serenely, stood, and switched off the radio.

In quick succession, like an echo, bells on every floor of the museum began to ding. That meant someone was at the doors.

“I’ll get it!” Thomas said. He didn’t bother with the stairs but threw himself into the air duct, whose cover he kept loose for this reason.

Unlike some of the other performers—Danny, Betty, Andrew—Thomas looked completely normal. He was a little short for his age and a little skinny, too. He had a smattering of freckles across his nose, which was stubby, and straw-colored hair that never managed to lie flat. He had vivid green eyes that were, more often than not, trained on a book about mathematics, science, or engineering.

But he wasn’t normal—far from it. Thomas could bend his nose to his toes. He could flex his spine like an anaconda. He could squeeze himself into a space no larger than a child’s suitcase. His bones and joints seemed to be formed of putty.

Now Thomas shimmied down the narrow duct, counting the floors, and sprang free of the grate in the lobby, completely unconscious of the fact that he was sporting a small mass of lint on his head.

Mr. Dumfrey was already opening the doors, saying, “No need for all that fuss, Thomas. I have it.”

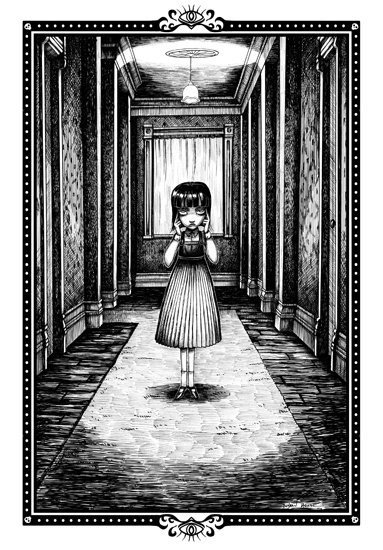

Just then, Thomas had the strangest sensation that reality had hit a snag, as though he were watching a play and one of the actors had skipped several lines. Afterward, he was to remember that moment for a very long time: the thin girl standing on the stoop in the rain, with the narrow face and wild curtain of dark hair, and the scar that stretched from her right eyebrow to her right ear, dressed in clothes three times too big for her and clutching a rucksack in one hand; and Mr. Dumfrey, his large, kind face so pale, it looked as though his head had been replaced with a pile of bread dough.

“It can’t be,” he gasped.

The girl frowned. “I heard an ad on the radio. You got a head here, don’t you?”

Dumfrey recovered somewhat. He swallowed loudly. “We have the only shrunken head in all of New York City,” he said grandly. “And the finest collection of freaks, wonders, and curiosities in the world.”

The girl sniffed and looked around the dingy lobby, where Andrew, the alligator boy (who was actually pushing seventy-five and walked with a cane), was playing solitaire behind the admissions desk, and several buckets had been set up to catch the rain where it was dribbling through a leaky window. “You looking for another act?”

“That depends,” Dumfrey said. Thomas noticed he was still gripping the doors, as though worried he might fall over. “What sort of act?”

Thomas did not see the girl reach into her pocket. He saw only the glint of metal in her hand, before, with quick, fluid grace, she rounded on him. He felt a wind whip past him, heard the thud of something on the plaster wall behind him.

Two high points of color had appeared in Dumfrey’s cheeks. He stood, eyes glittering, staring at a spot directly behind Thomas’s head.

Thomas turned.

Embedded in the wall, practically to its hilt, was an evil-looking knife, staked directly in the middle of a small ball of lint.

“You’re hired,” Mr. Dumfrey rasped.

The girl smiled.