3.00: Equipment and Uniforms

This is one of the few rules in the manual that has changed little since the first rule books were written. In the 1840s, balls differed substantially in both size and weight, depending on which team provided the game ball and where that team’s strength lay. A hard-hitting club was likely to furnish a tightly wound ball on the smaller side, whereas a nine that thrived on its defensive work, all of which at the time was performed barehanded, would select a heavier and softer ball.

In 1854, all organized clubs adopted the rule that balls must weigh between 5 and 5½ ounces and be between 2¾ and 3½ inches in diameter. The size and weight of ball changed twice more in the next thirteen years before the sphere settled on its present dimensions in 1868, as stipulated in Rule 1.09.

In 1879, the Spalding ball became the National League’s official ball, but the American League chose the Spalding-made Reach ball at its inception in 1900. The discrepancy ended in 1977, when both leagues began using Rawlings balls. Other aspirant major leagues used brands of balls that in most cases have long since disappeared from the market.

The National Association, the National League’s forerunner, used many different balls during its five-year run, from 1871 to 1875. When the American Association first surfaced in 1882 as a challenger to the National League, it chose as its official ball one made by the Mahn Sporting Goods Company of Boston. After using the Mahn ball for just one season, the AA abandoned it in favor of the Reach ball, which remained the official AA ball until the league ceased operation following the 1891 season.

In 1884, its sole year as a major league, the Union Association employed the Wright & Ditson ball, designed and manufactured by George Wright, the game’s first great shortstop and part-owner of the Boston Unions franchise. The Reach and Spalding balls in 1884 were quite similar, but the Wright & Ditson ball was a “hitter’s” ball, chosen in the expectation that fans would be drawn more to high-scoring games than a pitchers’ duel.

The official sphere of the Players’ League during the 1890 season, its lone campaign, was the Keefe ball, devised by Hall of Fame pitcher Tim Keefe, who hurled that year for the New York PL entry, and operated a sporting goods store in lower Manhattan in partnership with former teammate Buck Becannon. Like the Union Association’s Wright & Ditson ball in 1884, the Keefe ball was considerably livelier than its counterparts and throughout the early 1890s leftover Keefe balls would occasionally be slipped into a National League game at key moments when the home team—which was responsible for furnishing the balls—had the meat part of its batting order due up.

In 1914–15, the Federal League—the last serious threat to the two established major-league circuits—utilized a ball made by the Victor Sporting Goods Company, who were at the time one of the leaders in the business after it formed in 1898. It later merged with Wright & Ditson.

Before we leave the rule on balls, we call attention to the phrase “white horsehide.” Many readers will remember that in 1973, Oakland A’s owner Charlie Finley had his defending world champions experiment with orange balls in spring training exhibition games. But unlike many of Finley’s controversial innovations, this one died a quick death.

The last time a team played with balls that were a color other than white in a regulation major-league contest was in 1939, when Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail tried dandelion yellow balls in two games, one against the St. Louis Cardinals and one against the Chicago Cubs. The Dodgers first used MacPhail’s yellow balls in the first game of a Tuesday doubleheader with the Cardinals on August 2, 1938, at Ebbets Field, but met resistance from the other National League teams, especially after they won, 6–2, behind pitcher Freddie Fitzsimmons (who threw a complete game).

Until 1893, bats were permitted which had one flat side, making it easier for hitters to execute “baby hits” (bunts) and also to deliberately slap pitches not to their liking foul. First adopted by the National League in 1885, the flat bat was incorporated by the American Association when both leagues began using the same rule book in 1887. Even after being deprived of this advantage, many hitters—especially Willie Keeler, a leading exponent of the flat-sided bat—flourished in 1893 when the pitching distance was lengthened. As was true that year for hurlers who now had to tailor their deliveries to the increased distance, some batsmen were unable to adapt to bats that were entirely round and were soon out of the majors.

Harry Taylor.

The major leagues have, on occasion, authorized bats that were not all of a piece. During the 1954 season, for instance, laminated bats were allowed on an experimental basis. Bats made of metal, in whole or in part, have never been permitted in the professional game. . . and pitchers can only pray they never will be.

During his relatively brief career, Harry Taylor used a bat that was one of a kind and employed it in ways the likes of which have not been seen since. Later a renowned jurist, Taylor was active in the majors only four years (1890–93), but at the turn of the twentieth century he served as chief counsel for the players in their first attempt to form a union. Amazingly versatile, he made his ML debut with the Louisville Colonels in 1890 (at second base) after leading the New York State League in batting the previous year while playing shortstop for Elmira. When he left the majors after spending the 1893 season with the original Baltimore Orioles under Ned Hanlon, he was regarded as the best fielding first baseman in the game (and also had found time to catch, play the outfield, and serve in six games at third base). Offensively, Taylor had little power—as witness a career slugging average just 37 points higher than his .283 career batting average—but was an excellent baserunner and superb bunter with a technique that many tried to emulate but none ever mastered. Taylor used a bat made of soft wood, legal at the time, and would spin it at the last second as a pitch came plateward so that the ball would carom off the handle rather than the barrel and die just a few feet from the plate, forcing the surprised catcher to make the play rather than the charging pitcher or third baseman. But he also had another trick up his sleeve which exasperated pitchers nearly as much. Taylor was “double-jointed” and deluded umpires into calling pitches he swung at foul balls because his joints would “crackle on the swing,” making a sound like a foul tip, which as yet was not a strike. Most importantly, he was a respected field leader.

Beyond any doubt, the most famous violation in major-league history of Rule 3.02 (c) was the “Pine Tar Incident” in 1983, which began on July 24 at Yankee Stadium in a game between the New York Yankees and the Kansas City Royals, but echoed deep into the offseason and did not culminate until late that December when Commissioner Bowie Kuhn fined the Yankees $250,000 for “certain public statements” made by owner George Steinbrenner about the way American League president Lee MacPhail handled the situation.

The controversy was ignited by Kansas City third baseman George Brett’s two-run homer off Yankees reliever Goose Gossage with two out in the ninth inning, putting the Royals ahead, 5–4. As Brett started for the dugout after circling the bases, Yankees manager Billy Martin asked the umpires to check Brett’s bat for excessive pine tar. Like many players, Brett used pine tar on his bat handle to improve his grip and prevent blisters. But Martin, after being tipped off by third baseman Graig Nettles, contended the application extended beyond the allowed 18 inches from the end of the handle. Plate umpire Tim McClelland looked at the bat, then consulted with his three associates, and the onus fell on crew chief Joe Brinkman.

When Brinkman measured the pine tar on Brett’s bat handle against the 17-inch width of home plate, he discovered the substance exceeded the 18-inch limit by an inch or so. Whereupon the umpires ruled Brett out for using an illegal bat, to nullifying his home run and ending the game with the score reverting to 4–3, New York. Livid with rage, Brett raced back onto the field and had to be physically restrained from taking on the entire umpiring crew. While the argument raged around home plate, Royals pitcher Gaylord Perry furtively snatched Brett’s bat. Before he could make off with it, however, he was intercepted by a uniformed guard, who saw to it that the bat was taken to the umpires’ dressing room.

The Royals lodged an official protest with commissioner MacPhail. Four days later, MacPhail announced he was upholding the protest, marking the first time in his ten years as American League president that he had overturned an umpire’s decision. The commissioner contended the fault lay not with his umpires, however, but with the rule, which needed to be rewritten to make it clear that a bat coated with excessive pine tar was not the same as a doctored bat—one that had been altered to improve the distance factor or to cause an unusual reaction on a batted ball (a corked bat, for instance).

With the protest espoused, the score once again became 5–4, Royals, with two out in the top of the ninth. When MacPhail ruled the game had to be finished at Yankee Stadium on August 18, an open date for both teams, Steinbrenner at first said he’d rather forfeit. The completion of the game eventually took place as ordered by MacPhail in a near-empty ballpark, but not before there was attempt by Yankees fans to get a court injunction barring the game and a last-ditch effort by Billy Martin to have Brett declared out.

As soon as the two clubs took the field on August 18, Martin had his infielders try appeals at first and second base. When the umpires—not the same crew who had worked the original game—gave the safe sign, Martin filed a protest with crew chief Dave Phillips, contending that the four umpires could not know that Brett had touched all the bases on his home-run tour since none of them were in Yankee Stadium on July 24. But Martin’s argument had been anticipated. Phillips whipped out a notarized letter signed by Brinkman’s crew stating that Brett and U. L. Washington, the runner who had scored ahead of him, had both touched all the bases.

The game took only twelve minutes to complete, as the Yankees meekly went down in order in the bottom of the ninth to seal the 5–4 Royals victory. However, the various court actions that the Yankees launched to have the result quashed were only just beginning. In the end, none of them came to much, but over the winter the Official Playing Rules Committee clarified the so-called “pine tar rule” to stipulate, as per the note in Rule 1.10 (c), that, “a violation of the 18-inch limit shall call for the bat’s ejection but not for nullification of any play that results from its use.”

Ironically, the Yankees were themselves once victimized by Rule 3.02 (c) [formerly Rule 1.10 (c)] before it was rewritten in such a way as to avert incidents similar to the Brett debacle. In a 1975 game, on July 19 against the Minnesota Twins at Metropolitan Stadium, Yankees catcher Thurman Munson singled in the first inning to drive home a run, but was called out by plate umpire Art Frantz when an inspection of his bat, instigated by Twins manager Frank Quilici, disclosed that the pine tar on it overstepped the 18-inch limit. Billy Martin no doubt was aware of Frantz’s ruling eight years earlier when he requested that Brett’s bat be checked.

A question frequently asked by fans unfamiliar with the history of uniforms is: Why have the New York Yankees retired the numbers of all their immortals, such as Ruth, Gehrig, Mantle, and DiMaggio, whereas the Detroit Tigers have never retired Ty Cobb’s number? The answer has nothing to do with Cobb’s lack of popularity. Rather, it is that Cobb never wore a number during his playing days. Nor for that matter did Walter Johnson, Tris Speaker, Eddie Collins, Honus Wagner, or numerous other stars of Cobb’s era.

Although major-league teams as far back as the 1880s wore numbered uniforms on occasion, the experiment always failed, in part because few players fancied bearing a number on their backs like convicts. Not until 1929, when the Cleveland Indians and New York Yankees both adopted wearing numbers on the backs of their uniform blouses, did a team put numbers on its uniforms and keep them there. On May 13, 1929, at Cleveland’s League Park, fans were treated for the first time to the spectacle of every player wearing a numbered uniform, and received a further treat when the Indians won, 4–3, behind Willis Hudlin. Two years later, the American League made numbered uniforms mandatory, but the National League did not follow suit until a year later. Meanwhile, Ty Cobb retired in 1928 before the rule was put into place.

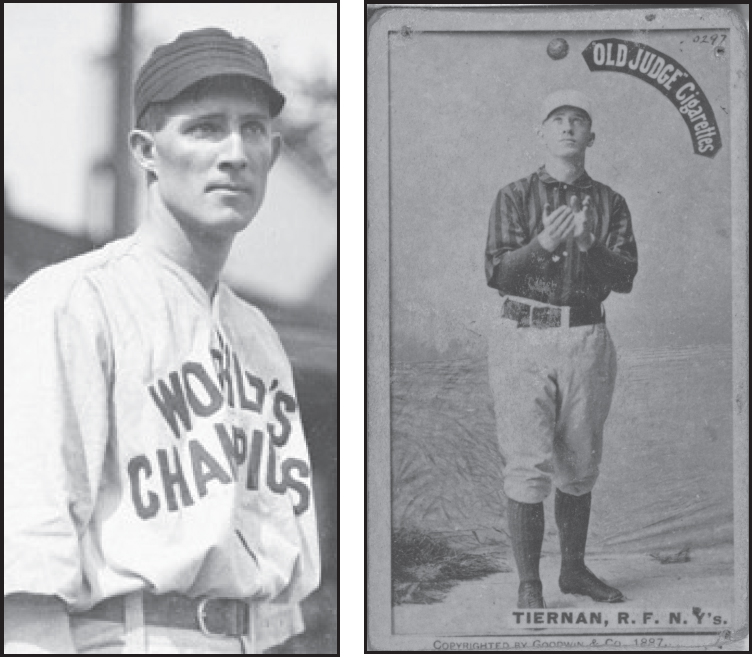

How, then, did fans go about telling players apart without them wearing numbered uniforms? In truth, they often didn’t—not even with a scorecard that listed that particular day’s lineups. Changes were oftentimes made at the last minute, and in the early days went unannounced to the general audience. New York Giants bleacher fans in the late 1890s had especial trouble telling Cy Seymour (left) and Mike Tiernan apart, and would often go through an entire game uncertain which one was playing left field, as both were left-handed, clean shaven, and roughly the same height and build.

It has always been customary for all the players on a professional team to wear identical uniforms, but not until 1899 was there a rule that every player on a team’s bench had to wear a uniform that exactly matched those of his teammates in both color and style. Prior to then, it had been an unwritten rule that many clubs violated—particularly when on the road and forced to pick up a last-minute substitute. To curtail expenses, teams sometimes took to the road with as few as ten players—the minimum a club could dress at the time—and then hired local amateurs from the city they were visiting when disabling injuries occurred. Often these major-league “temps” were outfitted with makeshift uniforms. In some instances a temp was even allowed to wear the uniform of his amateur club, supplemented by the cap of his major-league team for the day, and on at least one occasion a substitute played in street clothes. In an American Association game at St. Louis on May 10, 1885, John Coleman, a pitcher-outfielder who had not suited up that day, left the bench to replace Bobby Mathews in right field for the Philadelphia Athletics. Mathews had begun the game in the box but switched to right when he hurt his hand. Coleman replaced him in the sixth inning after Browns manager Charlie Comiskey acceded to the A’s request for an injury substitution.

In 1882, its first season as a rival major league, the American Association violated the uniform dress code custom for a very different reason, and the National League quickly followed suit. AA teams strove to be as gaudy in their attire as possible. At the opening of the inaugural season, clubs wore silk uniform blouses in as many different colors as there were positions on the diamond. The champion Cincinnati Red Stockings infield dressed as follows: First baseman Dan Stearns wore a candy-striped blouse, Hick Carpenter at third chose all white, and the two keystoners—second sacker Bid McPhee and shortstop Chick Fulmer—showcased purple and yellow-striped and maroon blouses, respectively. The National League, fearing that this innovation, bizarre as it seemed, might be received positively by the public, also voted to adopt color-coded uniforms at its annual meeting on December 9. 1881. The uniform experiment ended swiftly in both leagues after a string of comical on-field incidents made it apparent that fans and players alike were too often confused as to who was friend and who was foe.

The rule that all players must be wearing uniforms of exactly the same color harmed the Cleveland Indians in a 1949 game against the Boston Red Sox on September 20 at Fenway Park. Tribe ace Bob Lemon had a no-hitter going midway through the contest. It was a hot day, and before each pitch Lemon fell into the pattern of tweaking the red bill of his cap to rub the perspiration off his fingers. Observing that Lemon’s gestures were causing the bill’s color to fade as the game progressed, Red Sox manager Joe McCarthy claimed that it was no longer the same color as the cap bills worn by the rest of the Indians and therefore was not regulation. To avoid a rhubarb that would only further break his rhythm, as was McCarthy’s intention, Lemon obligingly changed caps, but the damage was already done. The Red Sox proceeded to knock him out of the box with five runs in the sixth inning. The following day Lemon, ever able to find humor in the game, appeared on the field in pregame practice wearing a fedora.

In the 2005 ALCS, fans had occasion to note that the strictures implied in stipulation (c) of Rule 3.03, as in stipulation (d) of 3.03 (see below), have been relaxed in recent years. Though the TV broadcasting crew made much of the fact that, in Game Two, Los Angeles Angels lefty Jarrod Washburn wore an undershirt with a red left sleeve and the right sleeve cut off at the armpit, an apparent violation of Rule 3.03 (c), White Sox manager Ozzie Guillen never lodged a protest. Since then the rules on uniform uniformity have grown even more permissive. In Game Three of the ALDS at Cleveland between the Astros and Indians on October 9, 2018, Indians third baseman Josh Donaldson wore the sleeve of a polka dot undergarment on his left arm the entire game without provoking comment from anyone. Earlier that season, in a July 4 game at Chavez Ravine, several members of the Pirates (but not all) wore polka dot undergarments, but no Dodgers took issue with it. In fact, polka dot undergarments have become commonplace with some teams. Similarly, players have begun stepping up their demands to wear shoes and cleats in the colors and designs of their choice.

Another long-standing custom that for many years was not formalized into a rule implored a team to possess two different uniforms; one to wear at home and the other while on the road. This practice first became an actual rule in 1904. Prior to then, it had been customary since the early 1880s for the home team to dress in white and the visitors in gray (or some other darker hue). Not until 1911 did it become mandatory, however, for the home team to wear white uniforms and the visitors dark uniforms as a way for fans, players, and umpires alike to distinguish more easily the players on one club from the other. In recent years, “may” has become the operative word in Rule 3.03 (d). Many major-league teams in the mid-1990s began wearing dark uniform tops at home, and some of the teams using dark tops at home also wore them on the road. The result is that, on occasion, the easiest way for a fan quickly to distinguish between the home and road team today, when both are wearing nearly identical dark tops (usually black), is to observe the uniform pants, which remain white for home teams and gray for road teams. The socks can also be a distinguishing feature—but not in all cases, since many players now, rather than the traditional knickers style, wear long uniform pants that cover their socks.

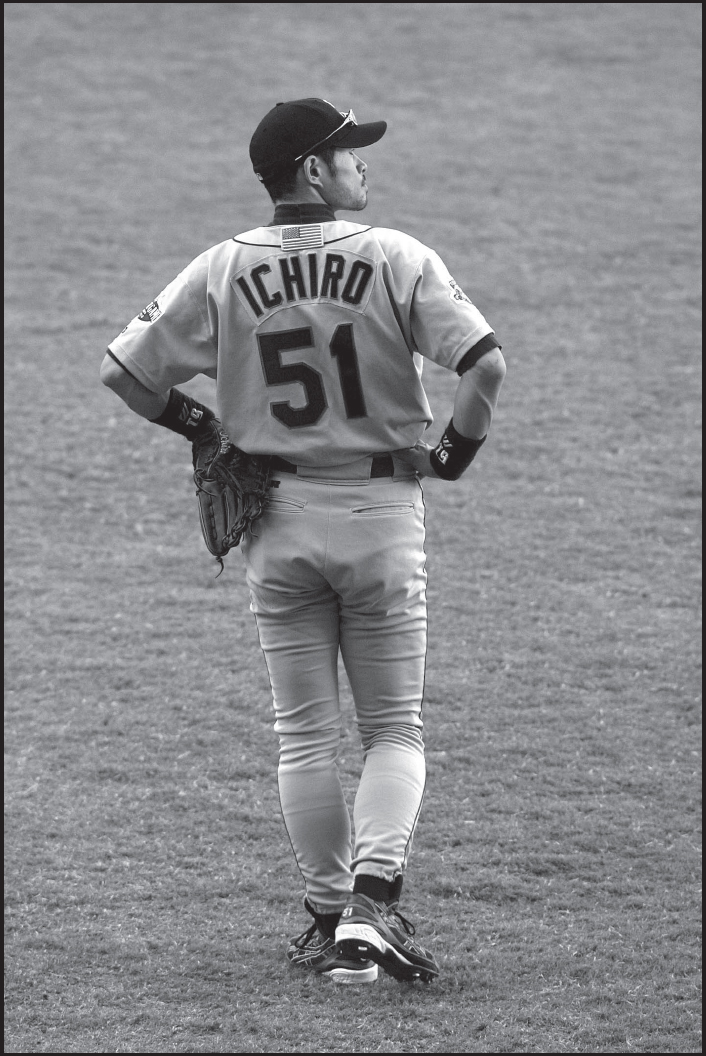

Special dispensation has to be granted from the commissioner’s office for a player to wear any name other than his surname on his jersey. The most recent player to be granted this privilege was Ichiro Suzuki, seen above.

Putting a player’s name on the back of his uniform jersey has been part of baseball for over half a century. It originated in 1960 by Bill Veeck while he owned the White Sox as a way of creating extra revenue by selling replica jerseys. Many of the smaller market teams still do it—especially when playing at home—but some of the wealthier clubs do not, although they encourage their souvenir shops to peddle jerseys with the names of their players on them. The Yankees are currently the only club that refuses to put names on both their home and road jerseys (though if you go to a store you can easily purchase a shirt or jersey with a player’s name, both past and present).

Rule 3.03 (e) is comparatively new to the manual and was formerly Rule 1.11 (c). When the entire rule book was rewritten prior to the 1950 season, it was spelled out for the first time that a pitcher could not wear a garment with ragged, frayed, or slit sleeves, but long before then umpires had begun making pitchers shed offending garments, albeit on an arbitrary basis. One who escaped punishment for many years was Dazzy Vance, whose blazing fastball was rendered all the more effective by the tattered right undershirt sleeve he flourished over the vehement protests of rival batsmen.

Cleveland Indians hurler Johnny Allen was not so fortunate. Long known for his monumental temper tantrums, Allen faced the Boston Red Sox in Fenway Park on June 7, 1938, with umpire Bill McGowan behind the plate. Allen and McGowan had crossed swords before, so the stage was set for sparks to fly as soon as Allen began to complain about McGowan’s decisions on pitches.

In the second inning, McGowan stopped play, strolled out to the mound, and told Allen he would have to cut off the part of his sweatshirt sleeve where he had cut diamond-shaped holes for ventilation, which made the sleeve wave whenever he delivered a pitch, a distraction to the batter. Allen refused to either remove the shirt or shorten the offending sleeve, and when he was confronted again in the top of the third inning, he stalked off the mound and vanished into the Cleveland clubhouse. Indians manager Ozzie Vitt promptly took him out of the game and fined him $250.

The offending shirt became a cause célèbre. When Cleveland owner Alva Bradley learned of the incident, he bought the shirt from Allen for $250—in effect paying the fine for his pitcher—and had it mounted in a glass showcase of the Higbee Company, a Cleveland department store. Bradley contended that the Higbee Company, and not he, had purchased the shirt, which may technically have been true. Bradley’s brother, Chuck, was the president of the Higbee Company at the time. By then the entire country knew the tale of Allen’s frayed temper and tattered sleeve. His shirt was eventually placed in the Hall of Fame as a reminder of one of the game’s wooliest episodes.

In the early days it was recommended but not mandatory that a player wear spikes attached to his shoes. Interestingly, most players then wore shoes of the same high-top design that is now the rage in baseball gear. Later all clubs made wearing spikes mandatory. The last player on record to be fined for not wearing spikes on his shoes was Pete Browning when he was with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1891. Browning hated to slide and lived in fear of having his spikes catch when he did so. He nonetheless stole his share of bases.

Players have never been permitted to wear golf or track spikes for obvious reasons: No second baseman or shortstop would ever have stood in to take a throw at the keystone sack on a steal attempt if a Ty Cobb or a Rickey Henderson had come into the bag with track spikes flying.

During the 1976 season, several players—including Dan Ford of the Minnesota Twins and Matt Alexander of the Oakland As—briefly wore spikes similar to those on golf shoes before a rival manager spotted the violation and protested to umpires, forcing the offending players to change to shoes with regulation spikes.

Without the comparatively recent addition of this rule addendum, one can readily imagine that the uniform jerseys of some of today’s players would resemble the uniform blouses of five-star generals. Rule 3.09 similarly applies to all playing equipment including gloves, bats, the bases, the pitching rubber, and both the pitcher’s toe plate and home plate.

In a sense, it was Hoyt Wilhelm—and other knuckleballers of his ilk—who generated a rule limiting the size of a catcher’s mitt. To help Gus Triandos and his other catchers handle Wilhelm while he was with the Orioles from 1958 to 1962, Baltimore manager Paul Richards had an elephantine mitt constructed that resembled the gigantic mockery of the catcher’s mitt that Al Schacht, the Clown Prince of baseball during the 1920s and 1930s, utilized in his comedy act. Even with the oversized mitt, Triandos still set all sorts of modern records for passed balls. On May 4, 1960, he became the first backstop in American League history to let three pitches get by him in a single inning. Less than a week later, Triandos’s backup receiver with the Orioles, Joe Ginsberg, tied his record. In 1962, another Baltimore catcher, Charlie Lau, fell victim three times in a single inning to the butterfly pitch.

After the 1964 season, the rules committee limited the size of a catcher’s mitt—not that the lack of a restriction had ever seemed to offer much help to Triandos and the other receivers who had to cope with Wilhelm. In 1965, the first year the new rule was in effect, Wilhelm, by then with the White Sox, contributed heavily to the 33 passed balls Sox catcher J. C. Martin committed to set a post-1900 major-league season record. But Martin is only tied for 221st on the all-time list. In the nineteenth century, until the pitching distance was increased in 1893, the 1891 season was the only one in which no catcher had at least 50 passed balls.

The 1895 season was the first that addressed gloves. As late as 1938, first basemen could still use a glove of any size or shape they wished. Detroit first baseman Hank Greenberg brought this custom to a halt when he concocted a glove with a web that looked like a fishing net. Prior to the 1939 season, a rule was inserted that a first baseman’s glove could no longer be more than 12 inches from top to bottom and no more than eight inches across the palm and connected by leather lacing of no more than four inches from thumb to palm. The “Trapper” model, which first appeared in 1941 and quickly became the standard glove for the first base position, was circumspectly designed to conform to the new rule.

Michael “Doc” Kennedy was the last known professional player other than a pitcher to play barehanded. He began his career as a catcher with a Memphis club in 1876, spent a short time in the majors, and finished in 1901 at age forty-seven as a gloveless minor-league first baseman with Buffalo of the Eastern League, although he may have worn a glove that season in the few games he caught.

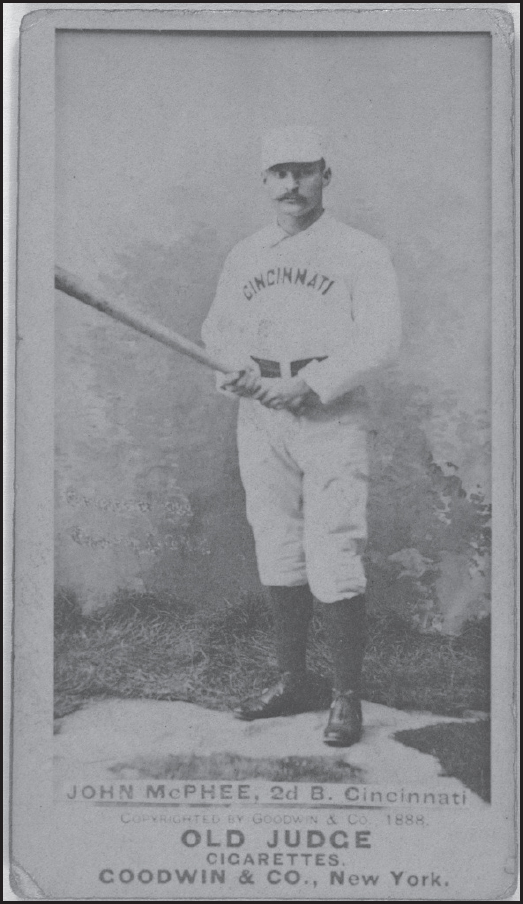

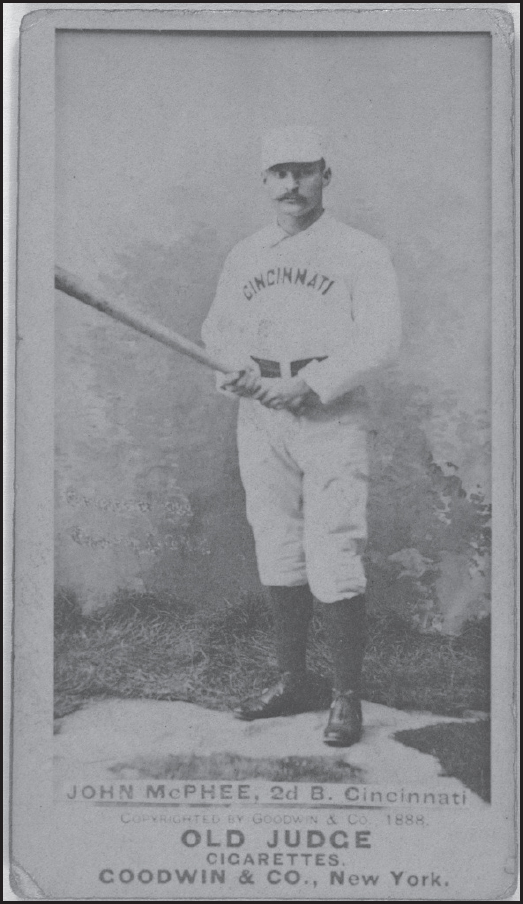

Prior to 1895, the rules said nothing about the size and shape of fielders’ gloves for the simple reason that for many years no self-respecting player would stoop to wearing a glove in the field. By the mid-1870s many catchers had begun using protective mittens while behind the bat and a few players, such as Al Spalding, also sported gloves that were employed more to protect their hands than to aid in catching the ball. However, gloves did not become a standard item of equipment until the late 1880s—even then a number of players disdained fielding a ball with anything but their bare flesh. The last two bare-handed major leaguers of note were second baseman Bid McPhee and third sacker Jerry Denny. Both balked at the notion of using a glove until the 1890s. Indeed, McPhee did not first wear a glove in the field until April 18, 1895, in an Opening Day game against the Cleveland Spiders.

Bid McPhee, the best second baseman in Cincinnati Reds history prior to Joe Morgan and the last documented major leaguer to play without a glove. Largely because he spent a significant portion of his career in the rebel American Association, McPhee was forced to wait until 2000 before being selected for the Hall of Fame.

Meanwhile, other players had long since recognized the advantages a glove could provide. When some began designing contraptions the size of manhole covers, a rule was devised in 1895 limiting fielders to gloves that could not be over 10 ounces in weight or more than 14 inches in circumference around the palm of the hand. Catchers and first basemen were exempted from any restrictions on the size or weight of their gloves, but were made to switch to a smaller glove if they played another position. For years afterward, however, it was still common practice for a former catcher like Lave Cross to use a modified catcher’s mitt to play the infield—especially third base—as long as his mitt did not exceed the proscribed 10-ounce weight and 14 inches in circumference.

Of the six appendices regarding helmet requirements and usage, several were long overdue when they were added—tragically long overdue. Among them is 3.08 (e) requiring all base coaches to wear protective helmets. It followed the stunning death of Tulsa Drillers first-base coach Mike Coolbaugh on July 22, 2007, after being struck while in his coach’s box by a line drive off the bat of Drillers catcher Tino Sanchez in the ninth inning of a Texas League game against the Arkansas Travelers. Sanchez’s blow struck Coolbaugh in the neck and destroyed his left vertabral artery, causing so severe a brain hemorrhage that he was virtually killed on impact. It is uncertain that even a standard protective helmet would have served as an adequate preventative measure in this instance.

The 1971 season was the first when it became mandatory for batters to wear protective helmets, but most had adopted them long before then. In 1941, the Brooklyn Dodgers became the first team to wear plastic headguards after Pete Reiser, Joe Medwick, and several of the team’s other stars were beaned. By 1957, the American League had recognized the need for protective headgear and made it obligatory. Batters had the option, though, of using plastic wafers in their caps, which offered less protection than a helmet—particularly one with ear flaps—but were more comfortable. The 1971 rule contained a codicil that permitted veteran players who preferred plastic wafers to helmets to use wafers for the remainder of their careers. Former catcher Bob Montgomery (1970–79) was among those who declined to wear a helmet, and has claimed that he was the last to bat in a major-league game without one.

Game photos from the 1960s reflect that some batters began wearing helmets on the bases even before the mandatory rule to wear them while batting was instigated. But curiously, the mandatory rule to wear them on the bases was not adopted until 2010.

Only someone under the age of seventy could ask if there is any truth to the tale that players in the old days were permitted to leave their gloves on the playing field while their team was at bat. But then many who are not yet senior citizens might consider 1953 the old days. That was the final season in which players on all levels could leave their gloves in the field when they came in to bat. The last players permitted to do so were the eight members of the New York Yankees who discarded them before they came to bat in the bottom of the ninth inning in Game Six of the 1953 World Series. The game at that point was tied 3–3, and saw the Yankees score the run that gave them the game, 4–3, and clinched the Series over Brooklyn, four games to two. Among the eight were seven of the usual suspects on the 1953 Yankees such as Mickey Mantle, Phil Rizzuto, and Gil McDougald, plus the one name that is guaranteed to win you a bar bet against even the most rabid Yankees’ fan you are likely to meet in your lifetime: first baseman Don Bollweg.

The popular custom was for outfielders to deposit their gloves near their positions, infielders to spread theirs around the edge of the outfield grass, pitchers to disgard theirs in foul territory, and catchers to haul their fielding tools into the dugout. Many players also left their sunglasses in the field, folded inside their gloves.

A thrown or batted ball that struck a glove left on the field was in play, and if a fielder tripped on a glove while chasing a hit, it was considered an occupational hazard. Everyone wondered how an umpire would rule if a fielder, while diving for a line drive, caught it with an opponent’s glove after somehow getting his bare hand entangled in it. But this unlikely event never happened (at least to our knowledge). What often did happen was that teammates or opponents of squeamish players would tuck rubber snakes and such in their gloves while they were left unattended and then wait for their owners to shriek when the repellent discovery was made.

Probably no one alive today ever witnessed a major-league game in which a batted ball or a player was affected by a glove lying on the field. Some fifty years earlier, however, on September 28, 1905, in a game that was instrumental in deciding the American League pennant, the Philadelphia A’s edged the Chicago White Sox, 3–2, when Topsy Hartsel scored the winning run from second base after Harry Davis’s single to short left field struck Hartsel’s glove, which he had left on the outfield grass when he came in to bat.

Rule 3.10 (originally Rule 3.14) was implemented in part for general safety, as by the mid-1950s improvements in design had created gloves with deeper pockets and fortified with webbing so intricate as to be a potential menace to fielders. No actual incidents were cited for this sudden change. After the new rule was adopted, some players, out of habit, continued to leave their gloves on the field until an umpire admonished them. Once in a while, before a glove was ordered removed, it would be allowed to remain on the field for a time, perhaps as a lorn reminder of a vestigial custom of the game whose passing most did not even know to mourn until long after the fact.

This rule was devised prior to the 2017 season after the New York Mets challenged the Dodgers’ use of a laser system to aid in positioning their outfielders in a game at the Mets’ Citi Field. The Dodgers argued that they had routinely made physical markings in the Dodger Stadium outfield and had offered opposing teams the same courtesy. Mets manager Terry Collins complained, “You just don’t go paint somebody else’s field.” Note that the new rule bans the use of physical markings but does not explicitly ban the use of lasers.

The illegal use of electronic devices in baseball suddenly became front-page news in January 2020 when the Houston Astros were punished for using a video camera positioned in center field of their home park during the 2017 season—their lone championship to date—to steal catchers’ signs. Team personnel, led by skipper A. J. Hinch and bench coach Alex Cora, watched the feed in a hallway between the clubhouse and dugout and then relayed what kind of pitch was coming by hitting a trash can with a bat. Houston’s proscribed use of electronics to steal catchers’ signs, though suspected, was not exposed in all its glory until former Astros hurler Mike Fiers told his Oakland teammates about it in 2019.

The investigation into the charge resulted in the Astros being heavily fined and stripped of their first- and second-round draft choices in 2020 and 2021. In addition, Houston general manager Jeff Luhnow and manager A. J. Hinch were suspended from baseball for a year and later fired by the club. Cora was also suspended for a year, and then bounced from his managerial post with the Red Sox; while Carlos Beltran, a key member of the 2017 Astros’ sign-stealing crew who retired after the season and had signed to manage the Mets in 2020, agreed with the club to part ways soon after the scandal broke. No active players were penalized because investigators and the MLB Players Association struck a bargain early in the process that granted immunity in exchange for honest testimony. It was widely believed that MLB was quick to make such a generous offer largely because it did not think it could win subsequent grievances with any players it attempted to discipline.

Whether the Astros profited significantly from their crime against the game is debatable. In both 2017 and 2018, their offensive numbers and won-lost records were better on the road than at home. Although they did better at home than on the road in 2019, the club dropped the seven-game World Series to the Washington Nationals after losing all four in their home park while winning each of their three road games by lopsided margins.

Sign stealing in baseball is as old as the first team to be detected giving its players “secret” signals. It is perfectly legal—except when it utilizes systems or techniques that MLB has formally banned. Few pundits imagine the Astros have been alone in recent years in working to gain an illegal edge, just as few believe that none of the current plaque owners in the Hall of Fame used PEDs. Rogers Hornsby once acknowledged that he’d cheated, or somebody on his team had cheated in almost every single game he’d been in, and other great players have made similar admissions. So, then, why were the Astros dealt with so harshly? One school of thought is the dark cloud that currently looms over their entire organization first started forming in the early 2010s when they were believed to be tanking year after year to gather top draft picks and accrue added money to spend on signing amateur free agents who were not part of the draft. True or not, they are at present the face of modern technology’s advantageous usage in sports at its worst.