A BALK is an illegal act by the pitcher with a runner or runners on base, entitling all runners to advance one base.

Imagine a fanatical discussion on the history of the balk rule and its many ramifications. There may have been one, but no inking of it has ever been found. Yet a form of the rule has existed since the Knickerbocker rules of 1845. Spectators and players alike were as confused by it then, as most are now. The current rule book dwells at several different junctures on all the movements a pitcher can make—or fail to make—that constitute a balk. Rather than treat each juncture separately, let’s try to abridge our subject by doing a short overview.

We start by saying that the first balk rule in 1845 was created for the same purpose each new version of it has served in the years since. Which is simply to prevent a pitcher from unfairly deceiving a batter or a baserunner so as to keep either or both off balance by enticing the batter to show his hand as to whether a sacrifice bunt or hit-and-run play is in the offing and by curtailing base stealing.

Forty years later, the first season that overhand pitching was universally legalized, the term had already begun to acquire its present meaning. A balk in 1885 occurred in any of the following instances according to then Rule 29:

(1) If the Pitcher, when about to deliver the ball to the bat, while standing within the lines of his position, makes any one of the series of motions he habitually makes in so delivering the ball to the bat, without delivering it. (2) If the ball is held by the Pitcher so long as to delay the game unnecessarily; or, (3) If delivered to the bat by the Pitcher when any part of his person is upon the ground outside the lines of his position.

The second type of violation was a matter of the umpire’s judgment, whereas the third referred to the boundaries of the pitcher’s box, which in 1885 was a 4 x 6 foot rectangle.

In 1893, the first year that the pitcher’s plate was established at its present distance from home plate, a pitcher was judged to have committed a balk if he did any of the following:

1. Made a motion to deliver the ball to the bat without delivering it;

2. Delivered the ball to the bat while his pivot foot was not in contact with the pitcher’s plate;

3. Made a motion to deliver the ball to the bat without having his pivot foot in contact with the pitcher’s plate; or

4. Held the ball so long as to delay the game unnecessarily.

Before the 1898 season, three more ways for a pitcher to balk were added:

5. Standing in position and making a motion to pitch without having the ball in his possession;

6. Making any motion a pitcher habitually makes to deliver the ball to a batter without immediately delivering it; or

7. Feigning a throw to a base and then not resuming his legal pitching position and pausing momentarily before delivering the ball to the bat.

Contingency 6 might seem unnecessary, since even if a pitcher somehow managed to delude a batter into swinging at a phantom pitch, it could not be counted as a strike. Generally, the ploy was not an effort to dupe the batter, however, but a baserunner for the purpose of getting him to stroll off the bag and then nailing him on the hidden ball trick. Before 1898, a pitcher could pantomime his entire delivery routine without having the ball in his possession. Further restrictions on what a pitcher could do while one of his infielders tried to pull off a hidden ball play were imposed in 1920, bringing the rule closer to 6.02 (a) (7) and 6.02 (a) (9), mandating that a balk be called whenever a pitcher stands empty-handed on or astride the rubber.

But though the 1898 balk amendments took a giant step toward the present rule, there was still one more important stride to be made. It was taken in 1899, when for the first time a balk was assessed if a pitcher threw to a base in an attempt to pick off a runner without first stepping toward that base. Prior to then, pitchers had been free to do just about anything they wished in trying to hold runners close to their bases, including suddenly snapping a throw to a base while looking elsewhere. Helped by the new balk rule, National League teams stole nearly 600 more bases in 1899 than they had the previous year, and the Baltimore Orioles set a modern single-season stolen base mark with 364 thefts. Before 1899, pitchers not only could fake throws to first, they could also twitch their pitching shoulders, swing their legs every which way, and utilize many other maneuvers that are now considered balks.

Until the 1954 season, the ball was dead as soon as a balk occurred. There were no exceptions. Regardless of what happened, the runner or runners on base moved up one rung, a ball was assessed if the pitch had been released, and that was that.

The old rule cost an offensive team on many occasions but none more dearly than in 1949, when it played a hand in deciding the National League pennant race. In a Saturday night game at St. Louis’s Sportsman’s Park on August 6, the Cardinals had Red Schoendienst aboard and cleanup hitter Nippy Jones at bat with two out in the bottom of the first against the New York Giants. On the mound for the Giants was lefty Adrian Zabala, one of the numerous players banned from Organized Baseball for five years after jumping to the Mexican League at the start of the 1946 season. The ban had been lifted by Commissioner Happy Chandler two months earlier, allowing Zabala to rejoin the Giants, for whom he had last pitched in 1945. During his forced vacation from the majors, he had acquired some bad habits while pitching in the outlaw Provincial League. Working out of the stretch with a runner on first, Zabala was caught in a balk by second-base umpire Jocko Conlan as he delivered the ball to the plate. Jones, not seeing the signal, concentrated only on the pitch and proceeded to belt it into the bleachers for an apparent two-run homer. However, the prevailing rule at the time canceled the four-bagger and allowed the runner to advance only from first to second. Forced to bat over, Jones flied out to end the inning.

Zabala was subsequently charged with two more balks that night, giving him three in the game to tie the then-existing single-game major-league record. But he was otherwise almost completely in command. The Cardinals managed to scratch out only one tally against him after being robbed of Jones’s two-run dinger, and lost the game, 3–1. Had that defeat wound up in the victory column instead, St. Louis would have finished the 1949 season in a tie with Brooklyn, forcing a best two-of-three pennant playoff.

In a final note of irony, Zabala won just two games in 1949 and never again pitched in the majors.

For all the attention lavished on fine-tuning the various references to balks in the rule book, we are still left to inquire if a pitcher can be charged with a balk if something totally out of his control occurs to interrupt his delivery with men on base. The perfect pitcher to ask would have been Stu Miller. In the first of two All-Star Games in 1961, on July 11 at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, Miller held a 3–1 lead for the National League stars in the top of the ninth when he ran afoul of the infamous “’Stick wind.” With runners on second and third, Miller all of a sudden felt himself being blown off the mound as he prepared to deliver the ball. After the second American League run came home on the balk, the tying tally crossed moments later when the gusting wind spun a roller out of third baseman Ken Boyer’s grasp.

The Americans went ahead, 4–3, with another wind-aided run in the top of the 10th, but then fell victim themselves to the elements. In the bottom of the frame, the NL rallied for two runs when the wind sabotaged Hoyt Wilhelm’s knuckleball and made it easy pickings for first Hank Aaron and Willie Mays and then Roberto Clemente, whose single drove home Mays from second with the winning run.

Despite committing the most famous balk in a midsummer classic and giving up three runs in the 1⅔ innings he worked in relief, Miller got credit for the victory.

The rule that a pitcher, following his stretch, must come to a complete stop before making his delivery was intended to prevent pitchers from quick-pitching in order to hold runners closer to their bases, but through the years it has meant chaos each time a campaign is waged to enforce it to the letter.

In 1950, when it was first expressly stated that a pitcher had to pause a full second after his stretch with a runner on base, 88 balks were called in the first two weeks of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League season after there had only been 54 balks in the two major leagues combined the previous year. Nonetheless, prior to expansion in 1961, the post-1893 record for the most balks in a season belonged to three pitchers with six apiece, last done by Vic Raschi in 1950. Another crackdown in the late 1970s saw Frank Tanana set a new American League single-season record for balks in 1978 with eight and Steve Carlton shatter the National League mark the following year by committing 11. In 1984, with enforcement of the complete-stop rule again more relaxed, Tanana tied for the AL lead in balks with just four and Carlton and Dwight Gooden shared the NL balk title with seven. Then, four years later, MLB moguls decided umpires were not uniformly calling balks and changed Rule 8.01 (b) from:

The pitcher, following his stretch, must (a) hold the ball in both hands in front of his body and (b) come to a complete stop; to:

The pitcher, following his stretch, must (a) hold the ball in both hands in front of his body, and (b) come to a single complete and discernible stop, with both feet on the ground.

The difference between the two rules is that the 1988 version replaced “complete stop” with “single complete and discernible stop, with both feet on the ground.” This slight change, designed to make balk calls uniform, instead kindled one of the most exasperating springs ever experienced by major league pitchers. Just six weeks after Opening Day in 1988, the Braves’ Rick Mahler perpetrated the 357th balk of that season, setting a new MLB record for most balks in an entire season, and it was only the middle of May! Not long afterward, Yankees skipper Billy Martin threatened to upset the applecart by having his pitchers come to a complete stop for five minutes between pitches. By the time the rule was once again relaxed after it threatened to make the game a travesty—junior circuit hurlers alone were assessed an all-time record 557 balks in 1988—A’s ace Dave Stewart had committed 16 balks, still the ML season record, and Rod Scurry of the Pirates racked up 11 in only 31⅓ innings, effectively destroying his bid to come back from a year in the minors after becoming involved with cocaine.

The culprit for the sudden balks explosion was thought without any evidence to support it to be then Commissioner Bart Giamatti, Pete Rose’s nemesis. Whether Giamatti, who banned Rose for gambling on baseball games, was the driving force that propelled balk totals through the roof in 1988 is still a matter of conjecture today, but all individual, team and league balks records set that season still stand and are highly unlikely to be seriously threatened in the near future.

A BASE ON BALLS is an award of first base granted to a batter who, during his time at bat, receives four pitches outside the strike zone or following a signal from the defensive team’s manager to the umpire that he intends to intentionally walk the batter. If the manager informs the umpire of this intention, the umpire shall award the batter first base as if the batter had received four pitches outside the strike zone.

Alexander Cartwright and his cohorts made no reference in their playing rules to a base on balls. The omission exists because until 1863 there was no such thing in baseball as a free trip to first base. To reach base, a player had to hit the ball, even if it took 50 pitches before he got one to his liking.

In the 1863 season, both balls and strikes were called for the first time, with a batter being granted his base after receiving three pitches that were adjudged balls. However, before an umpire was permitted to call a pitch a ball, he was first obliged to warn a pitcher an unspecified number of times for not delivering “fair” pitches or for delaying the game. In essence, far more than three pitches had to be delivered outside the strike zone before a batter received a walk.

In 1874, umpires were instructed to call a ball on every third unfair pitch delivered, meaning that nine balls in all were needed to draw a walk, though technically it came after three called balls. The rule was again amended five years later, allowing umpires to call every unfair pitch a ball until nine were reached. In 1880, a walk was pared to eight called balls and then to seven the following year.

The 1884 season saw the National League shrink the number of balls needed for a walk to six, but the American Association still required seven balls. In 1886, the AA dropped to six balls, only to have the NL again demand seven. The two leagues adopted a uniform code of rules in 1887, including a reduction to five balls. Finally, in 1889, the figure was set at four, where it has remained ever since.

In 1879, the last year that nine balls were required to walk, Charley Jones, at the time the game’s leading slugger, topped the National League with just 29 free passes, and there were only 508 walks issued throughout the loop. The league total more than doubled in 1881, when a walk came after six balls, and the figure continued to climb all during the 1880s—peaking in 1889—the first year that a batter could stroll to first base after only four called balls. That season, National League pitchers handed out 3,612 free tickets, 1,519 more than in 1888.

The BATTER’S BOX is the area within which the batter shall stand during his time at bat.

Cartwright et al also made no reference to batter’s boxes in their playing rules. In all forms of baseball prior to 1874, a batter had to stand with either his forward foot or his back foot on a line drawn across the center of the home-plate area. If a batter struck a pitch without having a foot on the line, the umpire simply called the resulting blow “no hit” and called the batter back to the plate. There was no other penalty.

The 1874 season introduced a 6 x 3 foot rectangular box for the hitter to occupy, thereafter known as the “batter’s box.” The dimensions were increased to the present 6 x 4 in 1886.

Unlike the early game, nowadays when a batter steps out of the box—causing a pitcher to pause in the middle of his delivery—the plate umpire will not call a balk. Instead, the arbiter will just signal that time is out and then resume the game as if the incident had not occurred. If in the umpire’s judgment the disruption was deliberate, he can take further action, including tossing the batter out of the game.

Before 1957, as a pitcher was about to deliver the ball, a batter was free to step out of the box and take his chances. The absence of an equivalent to current Rule 5.10 (f) opened the door to incidents like the one in Rule 5.10 (f) that occurred in a 1952 Western International League game. It also enabled a batter to try a ruse that is now regarded as unsportsmanlike conduct and may result in the transgressor being called out. With a runner on third base a batter in earlier times could drop his bat as the pitcher went into his windup in an effort to induce a run-scoring balk.

By the way, there is still nothing in the rule book to say that a player must have a bat in his hands as he awaits a pitch. Three is not even an edict that he has to be accompanied by a bat when he steps into the batter’s box.

A BUNT is a batted ball not swung at, but intentionally met with the bat and tapped slowly within the infield.

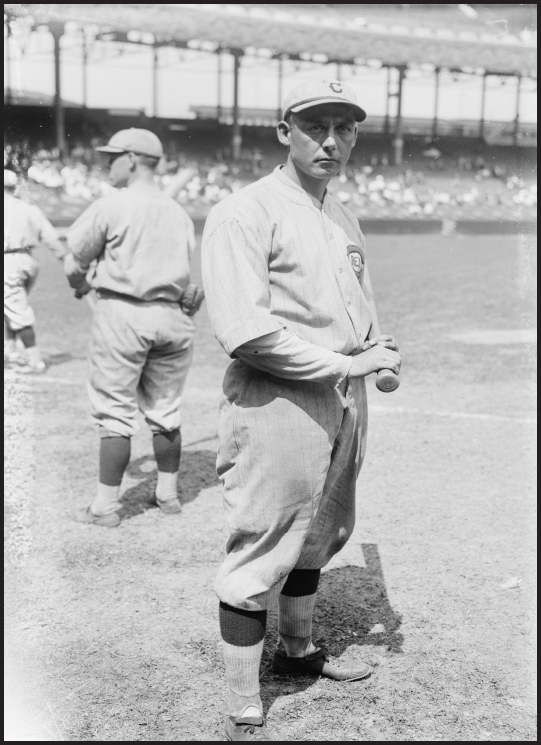

Hits that we now call bunts were originally known as “baby” hits. No one has a clue who coined the term “bunt.” It is even impossible to say for certain who laid down the first deliberate bunt. Some historians credit the gambit to Dickey Pearce, a stocky little shortstop active from the mid-1850s until 1877. A weak hitter even against underhand pitching, Pearce learned to bunt out of necessity, but whether he was the first to master the art will always be arguable.

A CATCH is the act of a fielder in getting secure possession in his hand or glove of a ball in flight and firmly holding it; providing he does not use his cap, protector, pocket or any other part of his uniform in getting possession. It is not a catch, however, if simultaneously or immediately following his contact with the ball, he collides with a player, or with a wall, or if he falls down, and as a result of such collision or falling, drops the ball. It is not a catch if a fielder touches a fly ball which then hits a member of the offensive team or an umpire and then is caught by another defensive player. In establishing the validity of the catch, the fielder shall hold the ball long enough to prove that he has complete control of the ball and that his release of the ball is voluntary and intentional. If the fielder has made the catch and drops the ball while in the act of making a throw following the catch, the ball shall be adjudged to have been caught.

(Catch) Comment: A catch is legal if the ball is finally held by any fielder, even though juggled, or held by another fielder before it touches the ground. Runners may leave their bases the instant the first fielder touches the ball. A fielder may reach over a fence, railing, rope or other line of demarcation to make a catch. He may jump on top of a railing, or canvas that may be in foul ground. No interference should be allowed when a fielder reaches over a fence, railing, rope or into a stand to catch a ball. He does so at his own risk.

If a fielder, attempting a catch at the edge of the dugout, is “held up” and kept from an apparent fall by a player or players of either team and the catch is made, it shall be allowed.

A runner was not permitted to tag up and try to advance on a caught fly ball until 1859. Until then, an “air” ball was dead as soon as it was caught and remained dead until it was back in the pitcher’s hands. But the 1859 amendment merely said that such balls were no longer dead. Four years later, the rule put into words that a baserunner had the right to advance after returning to his original base as soon as the ball had been “settled into the hands of a fielder.”

For many years the phrase “settled into the hands of a fielder” spelled trouble, especially for some umpires who took it to mean that a ball had to be firmly secured before a runner was free to tag up and advance. A number of outfielders became deft at juggling routine fly balls in order to hold a runner to his base while they jogged toward the infield until they were close enough to throw the runner out if he attempted to advance a base. Tommy McCarthy was supposedly a whiz at this trick when he patrolled the outfield with Hugh Duffy for the great Boston Beaneaters teams of the 1890s. But if McCarthy and other gardeners of his era were really so crafty, why was this apparent loophole not sealed up while they were still active (McCarthy, for one, finished in 1896)? In 1897, a rule at long last was created to thwart McCarthy et al, but only on balls that an umpire judged were juggled intentionally . . . not always easy to determine. In actuality, it was only in 1920 that the rule was finally altered to explicitly allow a runner to advance on a fly ball as soon as it touched a fielder, regardless of whether or not it was held secure. Meanwhile, two years earlier, a batting title was decided, owing largely to two umpires who were unfamiliar with the 1897 rule. But more about that in a moment.

Since the adoption of the 1920 amendment, on many occasions runners have advanced two and sometimes even three bases on a fly when an outfielder has juggled the ball or else fallen down or crashed into a wall after making a catch. At times a sacrifice fly has scored more than one run even though no errors or mishaps occurred on the play. Rocky Colavito, reputed to have one of the strongest arms in history, was once so victimized. Playing right field for Cleveland in the second game of a doubleheader with the Chicago White Sox on August 30, 1959, Colavito decided to showcase his arm in the top of the second inning on Barry Latman’s fly ball to deep right with John Romano on third and Al Smith on second. Knowing that Romano, a slow runner, would tag at third and try to score, Colavito put his all into a heave homeward and to his embarrassment saw the speedy Smith tally right behind Romano when his throw rainbowed and seemed to hang suspended in the air forever before it finally descended after both White Sox runners had crossed the plate.

As for the controversial batting title, it emanated from a game at Cincinnati on April 29, 1918, involving the Reds and the Cardinals. In The Complete Book of Forfeited and Successfully Protested Major League Games, Nemec and Miklich profile the key event, a deep fly ball to Reds center fielder Edd Roush in the top of the eighth inning of a 3–3 game with one out and Bert Niehoff of the Cards on third base. Niehoff tagged up at third, expecting to score the go-ahead run after Roush made the catch.

But the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that “just as [Roush] reached the ball he stumbled and fell to the ground. The sphere bounced out of his glove as he fell, but Edd twisted around and caught it in one hand as he hit the sward.”

Center fielder Edd Roush cost himself the 1918 National League batting crown when he caught a fly ball. Had he dropped it instead, as events played out for the remainder of the season he would have won the title.

Niehoff had left third base as soon as Roush touched the ball, and crossed the plate standing up. But Roush rose and threw the ball to second baseman Lee Magee, who fired it to third “where Heinie Groh was hollering for the ball. Groh tagged the bag and then appealed to umpire-in-chief [Hank] O’Day, who ruled that Neihoff had left third before the catch was completed and was thereupon the third out rather than the go-ahead run. The Enquirer said, “Hank’s decision on this play was a most unusual one, but eminently correct under the rules.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch was not so sure, especially after Cards skipper Jack Hendricks announced he was playing the game under protest when he failed to convince O’Day’s partner, [Bill] Byron, that Neihoff had every right to vacate third the instant the ball first touched Roush’s glove. It concluded: “It was a peculiar tangle, one that is now up to President [John] Tener to decide which is right, Manager Hendricks or Umpire Hank O’Day,” upon learning that Hendricks had made good on his threat and filed a formal protest immediately after the Reds tallied a run with two out in the bottom of the ninth off Cards starter Lee Meadows to win, 4–3.

On Sunday, May 12, Tener notified Cardinals president Branch Rickey that Hendricks’s protest had been allowed and the game of April 29 would have to be replayed in its entirety. Tener’s decision was based principally on O’Day’s frank admission that Neihoff had waited until the ball first touched Roush’s glove, but O’Day continued, wrongly, to maintain that “he should have remained on the sack until Roush entirely completed the catch.”

Plate umpire O’Day’s ignorance of the 1897 rule that favored the runner—even when a ball was not blatantly juggled intentionally (compounded by base umpire Byron’s ignorance of it as well)—is appalling coming from one umpire with over more than two decades of major-league service and another who was a future Hall of Famer. As for Roush, writer/researcher Tom Ruane discovered that his protested catch and assist on the inning-ending double play in essence cost him the NL batting title. He went 2-for-3 in the disallowed game. When it was replayed as the second game of a doubleheader on August 11, he got only one hit in four at-bats. Had the protested game not been thrown out, Roush would have finished with a .336 BA, one point ahead of the actual crown wearer, Brooklyn’s Zack Wheat, and five points ahead of Wheat if another protested game in 1918 (in which Wheat went 0-for-5) had not also been thrown out.

A considerably more famous debatable catch occurred seven years later in a World Series game. The rules as to what constitutes a legal catch make it clear that if an outfielder sees that a batted ball is headed for home run territory and catches it after jumping into the stands, it will still be a home run. If, however, he falls into the stands when jumping to make a catch, it will count as an out provided he catches and holds onto the ball. Any runners who are on base at the time will be allowed to advance one base.

The umpire can only make an educated guess sometimes whether an outfielder who disappears into the crowd in pursuit of a ball actually caught it. Probably the most classic example of an arbiter who was put in this unenviable spot came on October 10, 1925, during Game Three of the World Series between the Washington Senators and Pittsburgh Pirates, played at Washington’s Griffith Stadium—where temporary bleachers had been installed in right-center field to provide added seating. In the top of the eighth, with two out and the Senators ahead, 4–3, Pittsburgh catcher Earl Smith laced a long drive toward the temporary seats off Senators reliever Firpo Marberry. Washington right fielder Sam Rice (who had been moved from center to right earlier in the game) raced back for it, jumped to his limit, and toppled into the seats. For some 15 seconds Rice was lost to view, but at last he emerged from the crowd, holding the ball triumphantly over his head. Umpire Cy Rigler ruled it a catch, and thus began a furious argument. Eventually even Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss bowled through the crowd of players on the field to make his voice heard in the protest. Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountin Landis, in attendance, was at last persuaded to confer with Rice, hoping for clear directions, but Rice would only say, “The umpire said I caught it.”

In the end Rigler’s ruling stood for the lack of any contradictory evidence, and the Pirates lost the game, 4–3. Ironically, the game had earlier featured a sixth-inning home run by Washington’s Goose Goslin that bounced into the temporary stands. Rice lived nearly fifty more years without ever saying anything more definite about his play on Smith’s long drive than he had offered on October 10, 1924. It seemed that his epitaph would be: “The umpire said he caught it.” When Rice passed away, however, it emerged that he had left behind a letter to be opened upon his death. The letter averred that he had made the catch but provided no explanation for why he had refused to settle the issue while he was still alive.

A DOUBLEHEADER is two regularly scheduled or rescheduled games, played in immediate succession.

On September 9, 1876, the Hartford Blues and Cincinnati Red Stockings played two games against each other in the same day, the first such occurrence in National League history. But the pair of games was not a doubleheader in the strict sense.The first contest took place in the morning and then, after a dinner break, a second game was played in the afternoon. The first true major league doubleheader, wherein two games were played in immediate succession, came on September 25, 1882, when the Providence Grays split a pair at Worcester just four days before the Massachusetts club played its final game as a member of the National League. Worcester’s 4–3 win over Charley Radbourn in the first game of the September 25 twin bill was the last victory by a team representing that city in a major league.

Technically, purists insist the first doubleheader was a morning-afternoon affair that occurred at Boston on July 4, 1873, between the pennant-winning Red Stockings and the Elizabeth Resolutes, the weakest entry in the National Association that season. Amazingly, the New Jersey team—which left the loop a month later with a horrific 2–20 record—won the morning contest, 11–2, over Al Spalding, universally regarded as the top pitcher in the 1871–75 NA era.

As is still true in most minor leagues, the second game of a doubleheader was often scheduled for only seven innings in both major leagues prior to World War I. Much of the reason for the abbreviated second contest was because games in those days often did not start until mid-afternoon, making it a constant challenge to end before darkness. None of the parks as yet had lights, nor had Daylight Savings Time yet been imposed in the summer months. It need be mentioned that a number of seven-inning no-hitters that once were counted as complete-game no-nos are no longer listed among no-hit games because they went less than nine innings.

A FORCE PLAY is a play in which a runner legally loses his right to occupy a base by reason of the batter becoming a runner.

Even veteran umpires can be momentarily stymied as to whether a play is a force play. One such moment occurred in a June 28, 1998, interleague clash between the Mets and Yankees at Shea Stadium. With the game tied, 1–1, in the bottom of the ninth with one out, Carlos Baerga was on third and Brian McRae on first for the Mets. Baerga tagged up when pinch-hitter Luis Lopez skied a fly ball to Paul O’Neill in deep right. Recognizing that he had no chance to get the winning run at the plate, O’Neill simply lobbed the ball toward the infield after making the catch. But shortstop Derek Jeter noticed that McRae was almost standing on second base and winged the ball to Tino Martinez at first to double up McRae. The umpires then had to confer before ruling that Baerga’s winning run counted because, in their estimation, he crossed the plate before Jeter’s throw reached Martinez and McRae had not been retired on a force play. At the time there was no rule allowing video replay to confirm their decision.

If umpires are occasionally confused about this rule, players are even less informed on its complications. On June 10, 2010, in a night game at Minnesota’s Target Field between the Twins and Kansas City Royals, the home team had Denard Span on second and Nick Punto on third with one out in the bottom of the third inning when Joe Mauer hit a shot to deep center. Punto properly tagged up at third and started for home when Royals center fielder Mitch Maier caught the ball at the base of the fence. But Span, thinking the ball would hit the fence, took off at full tilt and was nearly at third when Punto glanced back and saw Maier make the catch. Punto yelled at Span to get back to second and then slowed to a jog upon realizing it was too late and that Span would be doubled off second for the third out. When Span was indeed doubled off, Punto was still a few yards short of the plate. Few in the park, least of all Punto, knew that he would have scored a run that counted had he crossed the plate before Span was retired. Even many sportswriters in attendance had to look up the rule later on after Kansas City won the game in 10 innings, 9–8.

Punto is somewhat unfairly singled out here; his mistake is a common one and often goes undetected by fellow players, sportswriters, managers, and broadcasters alike.

A FOUL BALL is a batted ball that settles on foul territory between home and first base, or between home and third base, or that bounds past first or third base on or over foul territory, or that first falls on foul territory beyond first or third base, or that, while on or over foul territory, touches the person of an umpire or player, or any object foreign to the natural ground.

A foul fly shall be judged according to the relative position of the ball and the foul line, including the foul pole, and not as to whether the infielder is on foul or fair territory at the time he touches the ball.

Prior to the twentieth century, a ball hit foul by a batter with less than two strikes was not deemed a strike. As a result, the American League record for the highest batting average was established in a season when the new loop did not yet recognize the foul strike rule. In 1901, while Nap Lajoie was hitting .426 to set an AL mark that looks unbreakable, the National League for the first time was counting any pitch fouled off by a batter with fewer than two strikes as a strike. The AL did not grudgingly follow suit until two years later. Hence Lajoie’s record—already suspect because the AL in 1901 was operating for the first time as a major league and many of its teams were stocked with marginal players—was further tainted by the fact that he was not charged, as were NL players that year, with a strike for hitting a foul ball.

In 1901, the AL outhit the NL by 10 points and upped the margin of difference to 16 points in 1902. The following year, the first in which both leagues counted foul balls as strikes, the NL outhit the AL by 14 points, seeming to support the argument that hitters had appeared to be superior in the AL during the previous two campaigns only because they were given the equivalent of an extra strike or two in many of their at-bats.

The history of the foul pole is a story unto itself. In the nineteenth century, although some parks had foul poles, there was no rule that one had to be equipped with them to help umpires determine whether a batted ball leaving the park was fair or foul. There was only this: “When a batted ball passes outside the grounds, the umpire shall declare it fair should it disappear within, or foul should it disappear outside of the range of the foul lines.”

Not until 1931 did the rule book say: “When a batted ball passes outside the playing field the umpire shall decide it fair or foul according to where it leaves the playing field.” By that time, there were foul poles in all major-league parks to help umpires gauge whether a ball was fair or foul as it left the park. Where it eventually landed was no longer of any relevance.

So how important are foul poles? In Pittsburgh’s final game of 1908, a makeup at Chicago on October 4 of an earlier tie game, the Pirates’ Ed Abbaticchio hit what appeared to some spectators to be a two-run homer in the top of the ninth into the right-field stands at Chicago’s West Side Park off a tiring Three Finger Brown to bring the Corsairs within one run of Chicago. But with no foul pole to guide him, Hank O’Day ruled the ball foul. Abbaticchio then struck out, Chicago won, 5–2, and the Cubs claimed the pennant three days later after winning a makeup contest for the famous Merkle tie game against the Giants by a one-game margin over the Pirates and the New York club. A female spectator later sued the Cubs for damages alleging that she was struck by Abbaticchio’s blast and swore the ball had been fair, citing the area she had occupied. But she made a hazy witness under interrogation and her claim was denied. Had it been true and ruled a home run on October 4, 1908, if Pittsburgh had won this game, Fred Merkle would be nothing more than a journeyman first baseman today and O’Day would have umpired his last game of the season and perhaps not reside now in the Hall of Fame, for Pittsburgh would have won the 1908 National League pennant with a 99–55 record.

An INNING is that portion of a game within which the teams alternate on offense and defense and in which there are three putouts for each team. Each team’s time at bat is a half-inning.

No one can answer who first brought the term “inning” to baseball. In his original playing rules, Alexander Cartwright made no mention of innings, calling a team’s stint at bat a “hand” and stipulating that even after one club achieved 21 runs or aces, a game could not end until an equal number of hands had been played. In Cartwright’s day, however, it was already common parlance to say a nine must be given its innings. The word inning is thought to have been borrowed from cricket and to signify a period of prosperity or luck. Certainly every team, from the dawn of baseball history, has looked to prosper when it took its turn at bat, but inning actually predates cricket and comes from the old English “innung,” which meant a taking in or a putting in.

INTERFERENCE

(a) Offensive interference is an act by the team at bat which interferes with, obstructs, impedes, hinders or confuses any fielder attempting to make a play.

(b) Defensive interference is an act by a fielder that hinders or prevents a batter from hitting a pitch.

(c) Umpire’s interference occurs

(1) when a plate umpire hinders, impedes or prevents a catcher’s throw attempting to prevent a stolen base or retire a runner on a pick-off play, or

(2) when a fair ball touches an umpire on fair territory before passing a fielder.

(d) Spectator interference occurs when a spectator (or an object thrown by the spectator) hinders a player’s attempt to make a play on a live ball, by going onto the playing field, or reaching out of the stands and over the playing field.

Of the four types of interference, spectator interference—especially on a fly ball—was the last to be specifically addressed in the rule book. This hazard did not appear there until 1954. That was the first season in which an umpire was licensed to declare a batter out on a foul or fair fly even when the ball was not caught, if in his judgment a fielder would have made the catch had a spectator not hindered the play. The key word here is judgment. Baltimore fans seated in the right field stands in Game One of the 1996 ALCS on October 9 at Yankee Stadium took vehement exception with right-field umpire Rich Garcia when Orioles gardener Tony Tarasco camped under Derek Jeter’s long fly to right in the bottom of the eighth inning and then watched helplessly as twelve-year-old Jeffrey Maier leaned over the outfield wall and spiked the ball into the stands. After seeing a postgame TV replay, Garcia acknowledged that he been wrong in awarding Jeter a home run to help give the Yankees a come-from-behind 5–4 victory, but AL president Gene Budig nonetheless denied Baltimore’s protest.

Seven years later, in Game Six of the NLCS on October 14, 2003, at Wrigley Field, Cubs loyalists nearly rioted when several spectators tried to snatch the Marlins’ Luis Castillo’s long foul fly down the left-field line in the top of the eighth inning that Cubs left fielder Moises Alou appeared to have lined up for a catch. Even though left-field umpire Mike Everitt ruled no fan interference, the blame after Alou failed to make the catch soon settled eternally on Chicagoan Steve Bartman when the Marlins rallied from a 3–0 deficit after Castillo reached on a walk and eventually won, 8–3, forcing a Game Seven. In both of these instances, the team that fell prey in front of millions of TV viewers to possible fan interference that was not then reviewable went on to lose the LCS and the pennant. For those of our readers who don’t yet know, the Cubs gave Bartman a World Series ring in 2016 after breaking the 108-year drought since their last world championship in 1908 and Bartman in turn broke his thirteen-year public silence since the incident.

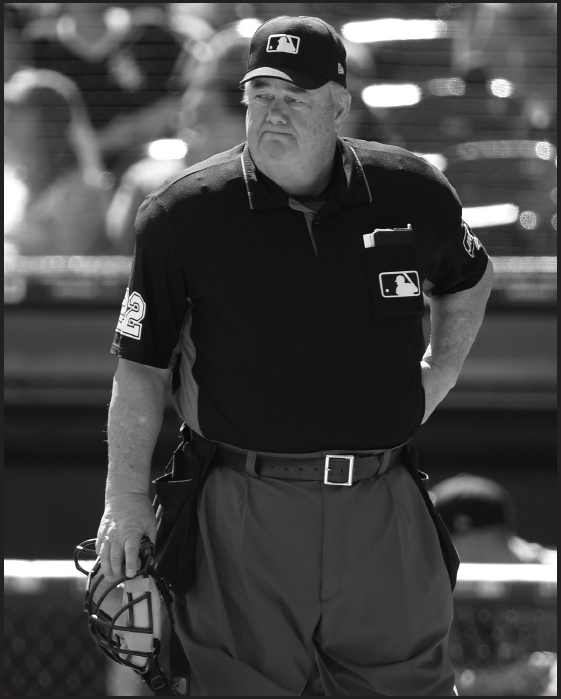

Joe West celebrated his record forty-first year in blue in 2019 and is second only to Bill Klem in the number of major league games he has officiated. In 2020, he in all likelihood will surpass Klem’s mark of 5,375 games.

Even though possible fan interference is reviewable now, events with game-changing and even postseason outcome implications still occur that are beyond the current scope of video review and may always be so.

A quintessential example came on October 17 2018, in Game Four of the ALCS at Houston. In the bottom of the first with a runner aboard and the Astros down, 2–0, Jose Altuve rifled a shot to deep right field that Boston right fielder Mookie Betts got in his sights at the base of the right field wall after a long chase. But when Betts leapt to make the catch, his glove was jostled by a spectator and the ball escaped his grasp and went into the stands for an apparent two-run homer. Right-field umpire Joe West promptly took the two runs off the board by ruling that Betts’s glove had been interfered with before it had crossed the railing above the wall. Houston fans in the immediate vicinity vigorously booed the call. A video review of the play was inconclusive because the view from the one camera angle in the right-field corner that would have clearly captured the location of Betts’s glove at the moment of spectator impact was blocked by other spectators who were on their feet to better observe the play. Consequently, West’s decision—even though many observers maintained he was poorly stationed to make the call—was perforce allowed to stand because there was insufficient evidence to overturn it. It would likewise have stood if he had ruled Altuve’s blast a home run. As it was, Houston lost the game, 8–6, and eventually the series, four games to one. As for West, he celebrated his record forty-first year in blue in 2019 and is second only to Bill Klem in the number of major-league games he has officiated. In 2020, he in all likelihood will surpass Klem’s mark of 5,375.

THE LEAGUE is a group of clubs whose teams play each other in a pre-arranged schedule under these rules [of baseball] for the league championship.

The first baseball teams to band together and play under the rules of the game—then in existence for a so-called “league championship”—were a group of sixteen New York clubs who gathered in 1857 to form the National Association of Base Ball Clubs. The fledgling loop played its games at the Fashion Race Course in Jamaica, New York, assessed spectators a 50-cent admission fee, and adopted the nine-inning format to replace the old first-team-to-score-21-runs-wins rule. All the players in the NABC were simon-pure amateurs, however, or at least that was the circuit’s claim; the notion of openly paying players to perform for one’s team was still more than a decade away from being popularly accepted.

The first all-professional league did not organize until 1871. Calling itself the National Association, it fielded nine teams and played its first game on May 4, 1871, with Cleveland (Forest Citys) facing Fort Wayne (Kekiongas) at Fort Wayne. The Fort Wayne club played just 19 championship contests before it folded, and no team played more than 33. By 1875, its last year of existence, the NA had swollen to fourteen teams, but only the top three—the Boston Red Stockings, Hartford Blues, and Philadelphia Athletics—played anywhere near a complete schedule. Rife with weak clubs, corrupt players, and lackadaisical team officials, the loop gave way the following season to a new circuit that christened itself the National League, and has remained alive under that name ever since.

A LIVE BALL is a ball which is in play.

BUT can more than one live ball be in play? Oh, yes. Throughout the rule book there is much discussion and many comments about what can happen while a ball is in play, but all of them skirt one of the umpire’s greatest nightmares: a situation in which there is more than one ball in play. Perhaps the most memorable occasion when this occurred came on June 30, 1959, in a game at Wrigley Field between the St. Louis Cardinals and Chicago Cubs. With one out in the fourth inning, Stan Musial of the Cardinals walked on a pitch that hit Cubs catcher Sammy Taylor and home-plate umpire Vic Delmore, and then skipped to the backstop.

Taylor thought the pitch had ticked Musial’s bat for strike two and began to argue with Delmore. When Musial saw that Taylor was otherwise absorbed, he rounded first and headed for second. Realizing what was afoot, Cubs third baseman Al Dark sped to the backstop to retrieve the ball. But before he could reach it, a batboy picked it up and flipped it to field announcer Pat Pieper. Surprised by the toss, Pieper muffed it and the ball bounded toward Dark, who scooped it up and flung it to shortstop Ernie Banks covering second base.

Taylor, meanwhile, had absently been given a second ball by Delmore as the two continued to argue. Cubs pitcher Bob Anderson, by then also part of the debate, grabbed the ball from Taylor when he saw Musial streaking for second and threw it over Banks’s head into center field. Musial, who had slid into the bag, picked himself up when he saw the wild heave thinking he had third base cold. But to Musial’s dismay, with almost the first step he took off second, Dark’s throw arrived at the bag, and before he could retreat Banks put the tag on him.

After a 10-minute delay while all four umpires—Delmore, Al Barlick, Bill Jackowski, and Shag Crawford—conferred, Musial was ruled out. The Cardinals lodged a protest, but it was withdrawn when they won the game, 4–1. We will never know what the ruling would have been had they lost.

The pitcher’s PIVOT FOOT is that foot which is in contact with the pitcher’s plate as he delivers the pitch.

Prior to the 1887 season, there was no such designation as a pitcher’s pivot foot and prior to 1893 there were no pitcher’s plates. As of 1887, the first season that the National League and American Association agreed to play by the same rules, the pitcher’s box was 5½ feet long (home to second) by 4 feet wide. Before delivering the ball, pitchers were required to have one foot on the back line of the pitcher’s box at all times, face the batter, hold the ball so the umpire could see it, and were allowed only one step or stride in their delivery. The pitching distance was now 55½ feet from the rear line of the pitcher’s box to the center of home base, but the front line was still 50 feet to the center of home base as it had been since 1881, thereby restricting a pitcher’s single stride forward to 5½ feet—a distance greater than most pitchers could manage with a single step. Hence most were no longer pitching 50 feet distant from the plate but as much as a foot or so more. Each corner of the pitcher’s box still retained either a 6-inch square iron plate or a stone marker.

In 1893, the pitcher’s box was abolished and replaced with a whitened rubber “pitcher’s plate,” that measured 12 inches (third to first) by 4 inches and lay even with the playing surface. The back of the pitcher’s plate was centered on an imaginary line drawn from the intersection of the third and first base foul lines to the center of second base. The new pitching distance of 60-feet, six inches was measured from the front of the pitcher’s plate to the intersection of the third and first base foul lines. The pitcher was required to keep his rear foot in contact with the rubber when he released the ball, but many hurlers found ways to fudge that requirement, especially when only one umpire was working the game. Some, like Pittsburgh’s Frank Killen, kicked dirt over the rubber, hiding it from view, and then pitched from several inches in front of it. Since the vast majority of games in the mid-1890s still had only one umpire, violations like Killen’s were seldom caught.

A QUICK RETURN pitch is one made with obvious intent to catch a batter off balance. It is an illegal pitch. Rule 6.02 (a) (5) Comment describes it in detail: A quick pitch is an illegal pitch. Umpires will judge a quick pitch as one delivered before the batter is reasonably set in the batter’s box. With runners on base the penalty is a balk; with no runners on base, it is a ball. The quick pitch is dangerous and should not be permitted.

Ever since 1887, when a pitcher first had to anchor his back foot before delivering the ball to the batter, there has been a rule of one sort or another against quick-pitching a batter, though it has not always been deemed a balk. In most cases, the pitch was disallowed. Babe Ruth once benefited enormously from such a judgment. In the final game of the 1928 World Series, the New York Yankees and St. Louis Cardinals were knotted at 1–1 in the top of the seventh when Ruth stepped into the box. Ruth already had one homer on the day, accounting for the Yankees’ only run. Lefty Bill Sherdel was on the hill for St. Louis. After getting two strikes on Ruth, Sherdel slipped a pitch past the Babe that everyone in St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park thought should have been a called third strike. But plate umpire Cy Pfirman, a National League official during the regular season, waved it off, saying it had been agreed before the Series that there would be no “quick returns”—pitches that were unacceptable in the American League but condoned by National League arbiters. Given a reprieve, Ruth clubbed a home run and Lou Gehrig followed with another four-bagger to put the game out of the Cardinals’ reach.

Quick pitching is seldom called by an umpire at the major-league level anymore, even though it’s been used on occasion in the past few years. But before the 1887 pitching rule change described earlier under Pivot Foot it was a staple of a number of prominent pitchers. Perhaps its leading exponent was southpaw Ed Morris—especially when he was caught by Fred Carroll. The pair were batterymates for seven seasons in the majors, beginning with Columbus of the American Association in 1884 and subsequently with Pittsburgh entries in three different leagues (the American Association, the National League, and the Players’ League). They mastered the quick pitch to a point where as soon as Morris’s delivery struck his mitt, Carroll would wing the ball back to Morris and the lefty would snag it barehanded and instantaneously fire it in again. In the days before advanced scouting, hitters seeing Morris for the first time were intimidated by this type of pitching. The two batterymates were also among the best of their time at holding runners; Morris had an excellent pickoff move (albeit no doubt an illegal one nowadays) and Carroll an extremely swift release on steal attempts.

In its early years, the National League put the batter at an even larger handicap to avoid being quick-pitched. Writer/researcher Richard Hershberger found the following discussion in the May 20, 1877, Chicago Tribune regarding an interlude the day before in a game between Chicago and St. Louis, which featured George Bradley and Cal McVey working the points for Chicago in its 7–1 win.

A question of rules arose yesterday which should not cause a moment’s doubt . . . It is well known that Bradley [pitcher] and McVey [catcher] have at times a trick of sending the ball back and forward with lightning rapidity . . . Yesterday they were putting [Jack] Remsen through this exercise, when he had two strikes in succession called and utterly losing his head he demanded “time” without alleging any reason, but clearly because he was being outwitted. The fact is, he didn’t know whether his head was under his arm or where it was, and he wanted to collect himself . . . The new clause of Sec. 7, Rule 2, which was introduced to cover such causes, is: “The umpire shall suspend play only for a valid reason, and is not empowered to do so for trivial causes at the request of a player.” It can hardly be said to come within this rule to stop play to throw the other side off their balance, or to give time to a rattled player to collect his thoughts. It is doubtful whether any excuse can be found for Remsen’s conduct in standing astride of the plate so as to stop the game until he got ready to have it go on again.

Unfortunately, little discussion of early-day quick pitch exponents can elsewhere be found.

A RETOUCH is the act of a runner in returning to a base as legally required.

This rule is seldom strictly enforced on a long foul ball down the line that, say, sends a runner on first base scampering almost to third before it is called foul so long as the runner passes in the neighborhood of second in returning to first. In any case, any missed base or failure to tag it is an appeal play by the defense; the umpire cannot initiate it. Nor can the team on defense initiate an appeal once the next pitch has been thrown. In the event a runner on any base does not tag his base of origin after a foul ball has been hit, he cannot be thrown out on an appeal in any case because the umpire-in-chief cannot put the ball in play again until every runner has properly tagged his base.

The STRIKE ZONE is that area over home plate the upper limit of which is a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants, and the lower level is a line at the hollow beneath the kneecap. The Strike Zone shall be determined from the batter’s stance as the batter is prepared to swing at a pitched ball.

In theory, the strike zone was changed in 1969 when it was reduced at its upper limit from the top of a batter’s shoulders to his armpits and at the lower limit from the bottom of a batter’s knees to the top of his knees. The truth, however, is that umpires subsequent to 1969 gradually shrank the upper limit of the strike zone until it became the beltline. To halt this practice, the Official Playing Rules Committee rewrote the definition of the strike zone prior to the 1988 season. But some older arbiters allegedly ignored it and still went by the pre-1988 strike-zone configuration, whereas others found it easier to picture the armpits as the upper limit rather than an imaginary midpoint between the beltline and the top of the shoulders. In 1995, the definition of the strike zone was again rewritten. Though umpires were strongly advised to adhere to it, some current players and managers still contend that too many umpires continued to fall into three groups: those that presume a pitch to be a strike unless there is a reason to call it a ball; those that presume a pitch to be a ball unless they deem it to be a strike; and the worst group of all, those that appear to have no regular approach at all to making ball-strike decisions. In recent years, however, to the displeasure of most umpires, electronic pitch-calling devices have been installed in many parks. Controversial as these devices are, their presence appears to have resulted in the strike zone becoming more uniform since, as we have already pointed out, they may otherwise one day strip this task from plate umpires.

Until the National Association came into existence in 1871, the strike zone was nebulous. Beginning in 1858, when the concept of calling strikes was first introduced, umpires were authorized to assess a strike on any pitch that was “within fair reach of the batter.” In 1871, the National Association adopted a rule that originated several years earlier, allowing a batter to request either “high” or “low” pitches. The strike zone for a high ball was between a batter’s waist and forward shoulder, whereas the low strike zone ranged from the waist to the forward knee. A batter was required to declare verbally his choice of pitches when he stepped up to the plate, and was not permitted to change his mind during his turn at bat. If a batter did not declare himself, the strike zone then became the entire area between the shoulder and the knee.

Quaint as the notion of a high and a low strike now seems, it endured for the first 16 seasons of professional play, from 1871 through the 1886 season. Prior to 1874, however, pitches in the wrong strike zone were not called balls but simply no pitches. In 1887, when the number of balls needed for a walk was pared to five and the number of strikes hiked to four, the high-low rule was eliminated. Confronting hitters with a strike zone double in size seemingly ought to have resulted in markedly lower batter averages, but quite the opposite occurred. Along with some major changes to the pitching rules, giving batters an extra strike and granting a walk after only five balls instead of six apparently more than compensated for the larger strike zone, at least in 1887.

By 1892, however, it was clear that a contrary adjustment was compulsory to restore a balance between hitters and pitchers, as the NL batting average that season plummeted to its 1880 level of .245. After considerable debate, the rules committee once again increased the pitching distance.

To compensate hurlers when the pitching distance was lengthened in 1893, groundskeepers followed an innovation that teams like the St. Louis Browns developed on the sly in the 1880s, claiming it quickened drainage of the infield after a rainstorm and began to raise the pitcher’s plate, centering it in a circular mound. There were no restrictions at first on how high a mound could be built. Teams like the New York Giants, with speedballers like Amos Rusie, consequently strove to have them tower above the batter, whereas clubs that were about to face Rusie in their home parks would shave their mounds the night before beginning a series with the Giants.

These sorts of shenanigans went on for a full decade since there was nothing in the rules to prevent it. Indeed there was nothing at all in the rules about mounds! Then, in 1904, all organized professional leagues adopted a rule that the “pitcher’s plate shall not be more than 15 inches higher than the baselines or the home plate . . . and the slope . . . shall be gradual.” The new rule was the first even to acknowledge that a pitcher’s plate did not have to be level with the surface of the playing field.

In the late 1960s, the game’s moguls faced a similar crisis that had forced their brethren to lengthen the pitching distance in 1893. After Carl Yastrzemski set an all-time nadir for a major-league batting leader when he won the American League hitting crown in 1968 with a .301 average, Bob Gibson topped the majors with a microscopic 1.12 ERA, and Cincinnati was the only major-league team to average as many as four and a half runs a game, one of the changes instigated in an effort to restore the balance between hitters and pitchers was to pare five inches off the mound and reduce its maximum height to ten inches.

Batting averages rose in 1969, but not nearly as much as they had in 1893 after the pitching distance was increased. Continued experimentation with the rules was necessary in order to procure more offense. Among the changes that eventually impacted on the balance between hitters and pitchers were reducing the strike zone and, in the American League at least, legislating that a hitter could be designated to bat in place of the pitcher.

To many observers, the strike zone seems to have expanded in recent years, but MLB authorities insist it has not (even though team and individual batting averages have shrunk to alarming proportions and strikeouts have soared). In actuality, by some accounts pitchers in 2019 put the ball in the strike zone less than 50 percent of the time, relying on their speed and free-swinging batters to chase pitches—particularly high and low ones—that are well out of the zone. Additionally, with two strikes on a batter, the number of pitches in the strike zone dropped below 40 percent. Whatever the truth of the matter is, it is a deeply disturbing reality that in 2018, for the first time in major-league history—in addition to there being a record number of batter strikeouts for the 13th straight season—the number of batter strikeouts (41,210) exceeded the number of base hits (41,019). It should also be duly noted that MLB conducted a novel experiment in the independent Atlantic League, its pet testing ground, in 2019. To coax pitchers back into the strike zone, particularly when the bases are empty, the Atlantic League allowed batters to run to first base and remain there if they reached it safely not just on a dropped third strike but on any mishandled or wild pitch regardless of the count.

A TAG is the action of a fielder in touching a base with his body while holding the ball securely and firmly in his hand or glove; or touching a runner with the ball, or with his hand or glove holding the ball (not including hanging laces alone) while holding the ball securely and firmly in his hand or glove. It is not a tag, however, if simultaneously or immediately following his touching a base or touching a runner, the fielder drops the ball. In establishing the validity of the tag, the fielder shall hold the ball long enough to prove that he has complete control of the ball. If the fielder has made a tag and drops the ball while in the act of making a throw following the tag, the tag shall be adjudged to have been made. In 2019, the following was added to the definition of Tag: “For purposes of this definition any jewelry being worn by a player (e.g., necklaces, bracelets, etc.) shall not constitute a part of the player’s body.” The same stipulation regarding jewelry worn by a player was added to the definition of Touch.

Again, we cannot be sure when the word “tag” became part of baseball lingo. In the infant forms of baseball, a fielder did not retire a runner by tagging him with the ball or tagging a base before he reached it but by hitting or “soaking” him with a thrown ball. This barbaric method had vanished by the time the Cartwright rules were adopted, but the idea of requiring a fielder to tag a runner was not embraced until 1848. Prior to that season, it had been possible to nail a runner at any base—including home—simply by tagging it before he got there. Runners in the pre-1848 era were tagged only when they clashed between bases with a fielder who happened to have the ball. As of the 1848 campaign, however, it became necessary to tag a runner coming into a base on any play except a force out.

A WILD PITCH is one so high, so low, or so wide of the plate that it cannot be handled with ordinary effort by the catcher.

Many games have been decided by a wild pitch. Perhaps the most renowned instance in postseason history came in decisive Game Five of the 1972 NLDS (when LCS’s were still best-of-five affairs) on October 11 at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium. The Reds entered the bottom of the ninth trailing the Pirates, 3–2, with relief ace Dave Giusti on the mound. After Johnny Bench led off the frame with a homer to tie the game, Giusti surrendered two more hits before giving way to Bob Moose, normally a starter. Moose retired Cesar Geronimo and Darrel Chaney, bringing up Hal McRae, who was batting for Reds reliever Clay Carroll. Moose unleashed a pitch in the dirt that eluded Pittsburgh catcher Manny Sanguillen, allowing George Foster to score the pennant-winning run from third base. It is still the only occasion in MLB history when a team trailed in the bottom of the ninth in a decisive winner-take-all postseason game and won it on a wild pitch.

Note that the final game of the 1886 World’s Series between the National League champion Chicago White Stockings and the American Association champion St. Louis Browns was also decided by Curt Welch’s purported “$15,000 Slide” (he actually scored standing up) in the bottom of the 10th inning after Chicago’s John Clarkson delivered a wild pitch with Welch on third to give St. Louis a 4–3 victory in Game Six of the Series. But it was neither a decisive winner-take-all game (as St. Louis was leading three games to two at the time), Nor was St. Louis behind when it took its final at bats.

WRENCHES IN THE WORKS

A term that is not yet in the rule book but ought to be. MLB contends that the game is healthier than it’s ever been, but attendance has been on a steady downward trend for several years and was at its lowest since 2003 in 2019. Instead, fans are following the game more and more on their cellphones or staying home to watch it on TV, where they get replays of almost every moment of interest they may have missed. And what are major league owners doing to bring people back to the parks? They are raising ticket and parking prices, constantly trading favorite players or letting them become free agents, tinkering with the rules after decades of almost no changes, and either eliminating, truncating, or discouraging former staples like the intentional walk, the squeeze bunt, the hidden ball trick, and the hit-and-run that have generated excitement and surprise ever since the dawn of major league ball. In addition, this decline also came when MLB players hit more home runs than ever before, with two clubs (the Minnesota Twins and New York Yankees) becoming the first clubs to ever hit 300+ dingers in a single season. If the game thought that the long ball would solve all its problems, attendance totals said otherwise.

And the players? Who wouldn’t be the first to reject a three-year offer of $18 mil per annum from a perennial contender whom you’ve served loyally for a year or two to grab a five-year contract for $20 mil per annum from a team that hasn’t sniffed postseason play in over a decade?

In 2018, the Gallup Poll concluded that the 9 percent of Americans who mentioned baseball as their favorite sport to watch was the lowest percentage for the sport since Gallup first asked the question in 1937. Americans named baseball as the most popular sport in 1948 and 1960, but football claimed the top spot in 1972 and has been progressively the public’s favorite ever since, currently by nearly a 5-to-1 margin over baseball even though its popularity, too, is slipping due to issues unrelated to the rules, style or tempo in which the game itself is played. In fact, according to data compiled by the Sports Business Journal in 2016, baseball has the oldest average player age of any of the major American sports.

Former New York Mets second baseman Wally Backman, the manager of the independent Atlantic League’s Long Island Ducks—MLB’s preferred petri dish—bemoaned in 2019 the many ways the game has departed from the style in which it was played while he was still active. At the same time, Backman, guaranteed by nature to introduce a cataclysmic element in any major-league team that would ever dare to hire him as its dugout chieftain, acknowledges a new generation has taken over the game. “If you don’t want to do it,” he proposes, “then you just get out of the game. Because things are going to change—that’s obvious.”

Backman understates the situation: Things have already changed. And skeptics have already connected the dots. To rekindle fan interest after the toxic 1994–95 strike, baseball moguls chose to ignore the herculean stats being posted by strongly suspected PED users. To win back the many fans whom the PED users soured on the game, MLB has introduced a ball that brings the same thrill, and even more often than the gigantic home run totals the PED users produced. Only it’s the ball that’s been ’roided now that the PED users have been weeded out to a large extent, and the public isn’t buying.

On August 10–11, 2019, the Wall Street Journal ran an article entitled “Juiced Ball Hits Triple-A.” The article categorically stated that, as promised in April 2019, the two Triple-A leagues—the International League and the Pacific Coast League—have switched to the same baseballs now used in the major leagues, unlike the less expensive balls used in the other minor leagues. The two top minor leagues were set on a pace to hit an astounding 2,100 more home runs combined than in 2018.

The official major-league ball is manufactured in Costa Rica and has higher specifications than minor-league balls. It also is constructed of slightly different materials than the minor-league ball. Minor-league baseballs are made in China and cost around half as much as the major-league balls, albeit their price is likely to go up owing to new tariff laws. the Wall Street Journal article confirmed that the current major-league baseballs have less air resistance and are more aerodynamic than the previous baseballs used.

Bob Nightengale wrote in USA Today on August 19, 2019: “The game is still played with the pitchers’ mound 60-feet, 6 inches from home plate, the bases 90 feet apart, three outs per half inning and nine innings in a regulation game. Those are about the only constants resembling the game of baseball as we once knew it.” Nightengale went on to cite the similar viewpoints held by former Cubs manager Joe Maddon (recently hired by the Angels) and longtime big-league fixture Lou Pinella among the several disgruntled baseball lifers he interviewed. He furthermore quoted Hall of Fame pitcher Goose Gossage as having said, “I can’t watch these games anymore. It’s not baseball. It’s unwatchable. A lot of the strategy of the game, the beauty of the game, it’s all gone. It’s like a video game now. It’s home run derby with their [expletive] launch angle every night.”

Don Malcolm, the provocative creator of The Big Bad Baseball Annual, recommends countering the game’s “escalating malaise” either by fixing the ball (extremely unlikely) or installing screens in all major- league parks, making home runs from “foul line to power alley distances achievable only with three or four times the present loft.” To his mind, the ideal configuration for the extra-base hit paradigm per game for each team is 1.7 doubles, 0.5 triples, and only, 0.9 home runs. If put to a vote among lifelong fans from all walks, a surprisingly high number may agree with Malcolm’s quotients, but among major-league players probably only pitchers, who are in the minority, would concur.

Baseball historian and critic Ev Cope observes that baseball is no longer “chess on grass” but “has become another sport of brute force—on the mound and at the plate. If ‘Inside Baseball’ is not yet dead, it is in intensive care.” Cope thinks this may simply represent “how American society has evolved. We seem to be more aggressive and not be as patient as we used to be, nor as sentimental. That proof is clearly evident in our or 3Ms: Media, Movies, and Music.”

Is all of this lamenting about the disappearance of so many treasured features of the pre-modern game even necessary, much less constructive? After all, every other major sport in America has undergone massive rule and equipment changes—including free agency—since baseball magnates shaved the mound to its present height in 1969, and none are the worse for it in the eyes of most of their ardent followers. Who is to say that in another few years the pitching distance won’t have altered, batters will no longer be able to get credit for an out-of-the-park home run (only a double) if they’ve previously struck out during the game, batters won’t automatically be deemed to have “fouled out” of a game when they whiff for a fourth time, and spectators won’t be able to place bets at their seats as to what a batter will do on every pitch?

Just too crazymaking? Maybe not.

Our only unequivocal assertion is that by 2025 a new edition of The Official Rules of Baseball Illustrated will be vastly different than this one.