29 TWENTY YEARS AFTER NATALIE WOOD’S death, as I was writing the last chapters of Natasha (the title of the first edition of this book), I felt a sense of urgency to get the pages into print. For more than four years, I had been the keeper of Natalie Wood’s deepest, darkest secrets—her crippling fears, harrowing superstitions, terrible incidents from her past that few knew of. Natalie never disclosed her history of trauma, except through her fragile vulnerability and in her tender, old-soul eyes.

As I plumbed her past, Natalie’s demons and their origins revealed themselves to me as if released from a genie’s lamp. Family violence. An alcoholic father. A pathological attachment to her Svengali stage mother. Psychological abuse as a child star. Paranoias. Phobias. A bedroom of storybook dolls she believed were alive and spoke to her. Pimped at fifteen to Frank Sinatra. Forced to return an engagement ring to her high school sweetheart, who tried to kill himself afterward. Exploited into a sexual liaison as a teenager with forty-two-year-old director Nicholas Ray to prove that she could play a “bad” girl in Rebel Without a Cause.

The secret that was buried deepest in Natalie’s closet of skeletons was the shocking end of her fairy-tale first marriage to bobby-socks idol Robert Wagner. To protect Wagner’s image, Natalie publicly took the fall for their sudden divorce in 1961. She never refuted fan-magazine gossip that her marriage to Wagner imploded over an alleged affair she had with her costar Warren Beatty while filming Splendor in the Grass. In time, the gossip, patently false, was reported as fact. Only a trusted few knew Natalie’s account. I was told by three of Natalie’s close friends, by her mother’s best friend, and her sister Lana that Natalie came upon R.J. in their Beverly Hills mansion in flagrante with a man. Lana recalled Natalie’s arriving in hysterics at their parents’ house, her hand bleeding, and shutting herself in her old bedroom. Natalie woke up in a hospital after taking an overdose of sleeping pills, dazed and in shock. That was as much as I wrote. But there is more to that story, too.

The fallout from a lifetime of psychological damage and abuse led Natalie to multiple suicide attempts, daily psychoanalysis, and a fear of being alone at night so primal and deep-seated that she regressed to her child self. Her greatest fear, I discovered, derived from a prophecy told to her superstitious Russian mother by a Gypsy—namely, that she would die in dark water.

I also discovered that Natalie Wood’s drowning was not an accident.

Homicide detectives in the L.A. Sheriff’s Department keep what they call a “murder book,” the official record of a homicide investigation. I was given access to Natalie Wood’s murder book. There I found the buried clues to what really happened on the last weekend of her life. As the evidence slowly, painstakingly mounted, it became disturbingly clear to me that not only was Natalie’s death not an accident, but the ensuing investigation was almost nonexistent.

As a self-described dutiful child, Natalie was trained by her mother to keep silent, to not rock the boat. As she got older, she kept her silence, often to protect others, as was Natalie’s way. During her life, in death, even after her death, no one, that I could see, had ever protected Natalie. Certainly not her mother, the directors who exploited her, the studio executives who looked the other way, the men who abused her, or the sheriff’s detectives and coroner’s examiners investigating her drowning in 1981. In the archive of forgotten facts, hidden truths, and concealed evidence about Natalie Wood, what is most shocking is Robert Wagner’s role in her drowning. The man whom Natalie Wood married not once but twice, who would often say, with glass raised, “She takes my breath away,” refused to allow a search for two and a half hours when Natalie went missing from their boat in the waters off Catalina Island.

Of all Natalie Wood’s secrets that I held in 2001, that secret was the reason for my urgency: I had come to realize the unimaginably horrible reason that she had drowned, and I needed to make public the dark and twisted facts of her drowning and its aftermath. I had uncovered the facts using the Sheriff’s murder book, put them together, and strung them in a row like lights on a Christmas tree, revealing the full horror of that strange, doomed night. It would not change the outcome of Natalie Wood’s drowning, but it would be evident, after Natasha, that she did not cause her own death because she was drunk from wine and champagne, as the coroner Thomas Noguchi stated. People would come to see, as I had, that Natalie Wood’s drowning was not an accident.

To understand what happened to Natalie that last night in all of its dark Russian drama, people needed to know Natalie Wood’s complete story—from her birth, as Natasha Zakharenko, prophesied, before conception, to become a world-famous beauty by a Gypsy in Harbin, to her death at forty-three, which Natalie had a premonition would be in dark water, as the same Gypsy had predicted.

Natalie Wood, tragically, was gone, and I could not bring her back, but I could tell her story. Through Natasha, Natalie would have a voice.

This is the rest of that story.

30 LESS THAN TWO WEEKS AFTER Natalie Wood drowned, the L.A. Sheriff’s Department, the office in charge of homicide investigations, ruled her death an accident. The case was closed on December 11, 1981. The official cause of death on Natalie Wood’s death certificate was “Accidental Drowning,” based on the autopsy findings filed by the L.A. Coroner’s Office.

I was predisposed to believe the same.

Who alive then had not been moved by the tragic breaking news on the Sunday after Thanksgiving in 1981? All of the major television networks interrupted their holiday programming to report that actress Natalie Wood’s body had been discovered floating in the ocean off Catalina Island, where she and Robert Wagner were spending the weekend on their boat with friends. Only later was it mentioned that actor Christopher Walken was their sole guest. Newsreel footage taken early that morning showed Wagner braced against the wind in a black, double-breasted peacoat with the collar turned up, looking dazed. That haunting image remains frozen in my mind to this day.

When I first took a biographer’s interest in Natalie Wood in 1997, it was her life, not her death, that intrigued me. In the sixteen years since she died, there had been occasional articles about her drowning but little about Natalie Wood, whose life had the drama of a Shakespearean tragedy, eclipsed only by her sudden, horrible death. It still seemed unimaginable to me, then, that her drowning was anything but an accident.

After years of rooting around in Natalie’s past, when I more closely examined her drowning, I found red flags everywhere. The Wagners’ deckhand, Dennis Davern, a footnote in news accounts of her death, had given a few stories to tabloids, at least one of them for the money, and he had aligned with a friend, Marti Rulli, to write a book. Davern’s accounts all included troubling insinuations about Robert Wagner’s role in Natalie’s disappearance from the Splendour. The details were vague, strange, and disturbing: There was a jealous tension from R.J. toward Natalie and Walken that weekend; Natalie requested to return to L.A.; R.J. directed Davern to take Natalie to a motel; R.J. smashed a wine bottle on the second night; the dinghy was unaccountably missing; R.J. instructed Davern not to search for Natalie as they drank for over two hours before R.J. radioed for help.

Both Davern and his spokesperson, Marti Rulli, came across as opportunistic. But Davern was one of only three people on the boat with Natalie that night—attention had to be paid. The more I uncovered about the official investigation of Natalie’s accidental drowning, the more Davern’s unsettling stories had the ring of truth.

To begin, there were gaping holes in coroner Thomas Noguchi’s findings. At a press conference on December 1, 1981, just two days after Natalie Wood’s body was discovered, Noguchi announced the autopsy results, stating that her cause of death was “a tragic accident while slightly intoxicated.” But he went on to mention an unexplained “scrape type of bruise on her left cheek” that may have rendered her temporarily unconscious before she hit the water. Noguchi’s theory was that Natalie was trying to get into the dinghy and must have scraped her face on the side of the boat. “Based on the available evidence and information,” Noguchi said tellingly (emphasis mine), “it appears that Miss Wood slipped when attempting to board the dinghy and accidentally fell into the water. She was unable to re-board the dinghy or the yacht and tragically perished.”

Noguchi’s conclusion was riddled with qualifiers and implausibility. For his theory to be true, Natalie had to have untied the inflatable dinghy herself, which he alleged. I had come to know, from interviews with those close to her and from Natalie’s statements through the years, that she would not have untied the dinghy. Her close friend Peggy Griffin had impressed on me what a stickler Natalie was for boat safety—it was raining, it was pitch black, and she was found wearing only socks, not deck shoes. It was hardly a time that Natalie would go to the rear deck to untie an eight-foot dinghy. Besides, there was a deckhand to do it for her. What’s more, with her terror of dark water, Natalie would not have stepped into a dinghy alone at night. The night before, in Avalon, she had been afraid to get into the dinghy even with her husband and Christopher Walken. On top of that, she never took the dinghy out alone. According to Davern, Natalie did not even know how to operate it.

What an aide of Noguchi did disclose, to great gasps from reporters, who sniffed scandal, was a “heated” argument between Robert Wagner and Christopher Walken before Natalie disappeared, a tip given to Noguchi’s office by a sheriff’s investigator. The argument was disturbing enough that Noguchi told the assembled press that he believed Natalie wanted to get off the boat. Noguchi also mentioned “recreational drinking” by the Wagner party and told reporters he estimated that Natalie had had seven to eight drinks, chivalrously describing her as “slightly intoxicated.”

From this thin, unsupported premise—Noguchi’s feeling that Natalie wanted to get off the boat and into the dinghy—Coroner Noguchi officially concluded, “It is unfortunate that wine and champagne caused a tragic accident.”

When asked by one of the reporters why Natalie Wood would leave the boat in a nightgown, Noguchi replied, “We are going to investigate that.” He intended to do a “psychological autopsy” on Natalie to learn why she felt she had to separate herself from her husband and Christopher Walken.

After this disclosure, Noguchi was almost instantly fired and removed from office by the Board of Supervisors—under pressure, he and his lawyer told me, from Frank Sinatra. “I represented Dr. Noguchi then,” said Godfrey Isaac, “and Frank Sinatra got very upset. The letter from Frank Sinatra to the Board of Supervisors is really what triggered them demoting Tom. And [revealing] that argument was the trigger of the removal of Tom from the Coroner’s office.”

Frank Sinatra’s strong-arm tactics with the coroner’s office were not surprising. The director Henry Jaglom had told me how Sinatra kept Natalie under surveillance by his “goons” when Jaglom took her out in her midtwenties; a protective, and proprietary, interest that began, I had learned, when Natalie was fifteen.

Two years after I wrote Natasha, Frank Sinatra’s right-hand man of fifteen years, George Jacobs, wrote a memoir called Mr. S: My Life with Frank Sinatra. Jacobs, who worked for Sinatra from 1953 to 1968, was a silent accomplice to his boss’s sexual assignations. “One affair that, unlike the others, was conducted in top secret was with Natalie Wood,” Jacobs wrote in 2003, “because she was a minor at the time, either fifteen or sixteen, though she didn’t act like it.” According to Jacobs, “Sinatra adored this tiny beauty, but he didn’t want to go the way of Charlie Chaplin or Errol Flynn, or later, Roman Polanski.” Jacobs mixed the drinks, he said, when Natalie’s “insanely ambitious Russian mother” brought her to Sinatra’s apartment for a cocktail in 1954 and “pushed her on Frank, who needed no pushing.” Sinatra told Jacobs that he had been “taken by” Natalie since Miracle on 34th Street, a film she made when she was eight. Sinatra’s procurer, Natalie’s mother, Maria Gurdin, “had her kid all dolled up,” recalled Jacobs, “total jailbait, in a form-fitting black party dress, and Mr. S went for it in a big way.”

Frank Sinatra’s MO with teenage Natalie was like a playbook for aspiring Humbert Humberts. “Nothing dirty-old-mannish,” his valet boasted, “he was never like that. He played them cuts from his upcoming album, provided career suggestions.” That was the quid pro quo for Maria Gurdin. After cocktails, Sinatra arranged for Natalie to return regularly, alone, for “singing lessons.” “Mr. S would send me away when she was there,” recalled Jacobs. “ ‘I don’t want you to testify,’ he joked. He wanted to be ‘In Like Flynn,’ but he didn’t want to be ruined for it.” When I discovered and wrote about Natalie’s teen interludes with Sinatra, it seemed implicit that Sinatra was intimate with her. His right-hand man appeared to have all but spelled it out.

George Jacobs observed what I too found. “Mr. S truly cherished her, and whatever went on in private, he was also a father to her more than her own father, very protective.” Jacobs’s insight, gleaned from years of observing Sinatra with Natalie in his home, sheds even more light on how disturbing their affair was. The thirty-eight-year-old Sinatra’s “seduction” of fifteen-year-old Natalie Wood, tragically, would have been both child molestation and statutory rape. Scott Marlowe told me he had observed signs that she’d been molested. “How do I say this delicately?” he asked. “She was very, very experienced for a very young girl. She knew too much. More than a kid that age should know. She just knew about all the men’s body parts. And about what to do, how to please, or how to get herself…loved. She knew all those little things. And it was very sad. I was aware of it from the beginning.”

Post-autopsy, in late 1981, Sinatra was furious that L.A. coroner Thomas Noguchi made public that Natalie had had too much to drink the night she drowned, and that the Wagner party was drinking “recreationally.” Sinatra was even more enraged that Noguchi disclosed at a press conference that his great friend R.J. had had a heated altercation with Christopher Walken before Natalie disappeared from the boat. To shield R.J. from further scrutiny, Sinatra pressured the L.A. Board of Supervisors to fire Noguchi in a scathing letter insisting that coroners “should be seen and not heard.”

Ironically, in his blind loyalty to R.J., Frank Sinatra betrayed his “cherished” Natalie. By his own description, R.J. had made a career from the favors and good graces of famous friends, names he liked to drop, like Fred Astaire, Clifton Webb, and “Spence” Tracy. According to George Jacobs, R.J. ingratiated himself with Sinatra so deeply that Sinatra “always gave him ‘a pass.’ ” By precipitating Noguchi’s firing, Sinatra shut down the coroner’s psychological autopsy, an in-depth investigation into why Natalie may have wanted to separate herself from her husband and Walken. It would have been the last, best hope for any of Natalie’s truths to be known in an official investigation of her death.

Noguchi’s unsupported conclusion of an accidental drowning, a finding that was still a work in progress, became Natalie Wood’s official cause of death because of Frank Sinatra’s influence. The secrets, phobias, betrayals, and terrors in the night that Natalie Wood hid so successfully from the public, crucial to decoding how and why she drowned, also remained hidden from the Sheriff’s Department’s lead investigator, Duane Rasure.

When I interviewed Rasure in October 1999, I was stunned by his incompetence. An amiable cowboy who had retired to Arizona from the sheriff’s office, Rasure was more invested in his hobby—redeeming the reputation of General George Custer—than he ever was in solving Natalie Wood’s drowning. He meticulously read aloud, verbatim, the notebook he made during his investigation of Natalie Wood’s death. I listened, at times incredulously, interrupting to ask questions.

Remarkably, Rasure seemed unaware of his deficiencies in investigating Natalie’s drowning or his almost complete lack of knowledge of the facts. As the lead homicide detective, it fell to Rasure to question key witnesses, most notably Robert Wagner. The interview took place a few hours after Natalie’s body was found mysteriously floating, facedown, in the ocean in a flannel nightgown, socks, and no underwear, far from the isthmus where their boat, the Splendour, was moored.

Robert Wagner was on his way off the island. Rasure met him for the interview at a heliport on Catalina, where a private helicopter had been arranged by the Sheriff’s Department to fly him to Santa Monica.

“I can remember this very vividly,” Rasure bragged, “because, you know, this guy’s a famous movie star and here I am, nobody. I’ve met a few movie stars in my business, but something this major, and I’m gonna work this thing, and I’m tuned on! I can remember him coming in the helicopter aero office, and I said, ‘I want to interview you in here.’ I got a hot cup of coffee in a Styrofoam cup. I handed it, like, do you want some? And he took it from me, and he sat there, we’re sitting side by side, he’s to my left, and I’m gently doing this, I mean not coming on like a detective. I’m just coming on like, ‘Tell me what’s happened.’ ”

After five minutes, Wagner cut off the interview. Recalling the moment, Rasure said proudly, “I got everything that I needed.” It apparently hadn’t occurred to Rasure to ask Robert Wagner, the last person to see Natalie Wood alive, how, when, where, or why she left the boat.

“She was a boat person, you know?” Rasure commented to me, repeating what he said Wagner had told him, still unaware of how incorrect it was. “She could drive a Zodiac, and quite often she or Wagner went out alone on this boat, so she knew what she was doing.”

At some point in our conversation, Rasure mentioned the possible existence of a murder book, the file of all the evidence in a homicide investigation, including a summary of the case, all interviews, investigative reports, field and lab reports, photographs, and printouts.

I needed to see Natalie Wood’s murder book.

31 ON A TIP FROM THE genial Rasure, I dropped his name to an LAPD detective, Louis Danoff, with the nickname “Sweet Lou,” and persuaded him to let me see the murder book for the Wood investigation, which did, in fact, exist. Within a week, I met Sweet Lou at a Sheriff’s Department office on the outskirts of downtown. My mother, who was in Los Angeles for Thanksgiving, came along, a camera tucked into her purse.

Sweet Lou escorted both of us to a small spare room. Inside were a long table and several chairs. I set up my laptop on the table and Sweet Lou returned with one or two boxes he identified as Natalie Wood’s murder book. Then he left the room and closed the door.

Uncertain how long I would have, what I was permitted to see, or whether I could document it, I began to enter the contents of the murder book into my laptop as quickly as I could type. I asked my mother to take photographs. We both kept an eye on the door, anxious that Sweet Lou might return with restrictions. Neither of us said anything. We both got the sense that we were looking at something that was not meant to be seen.

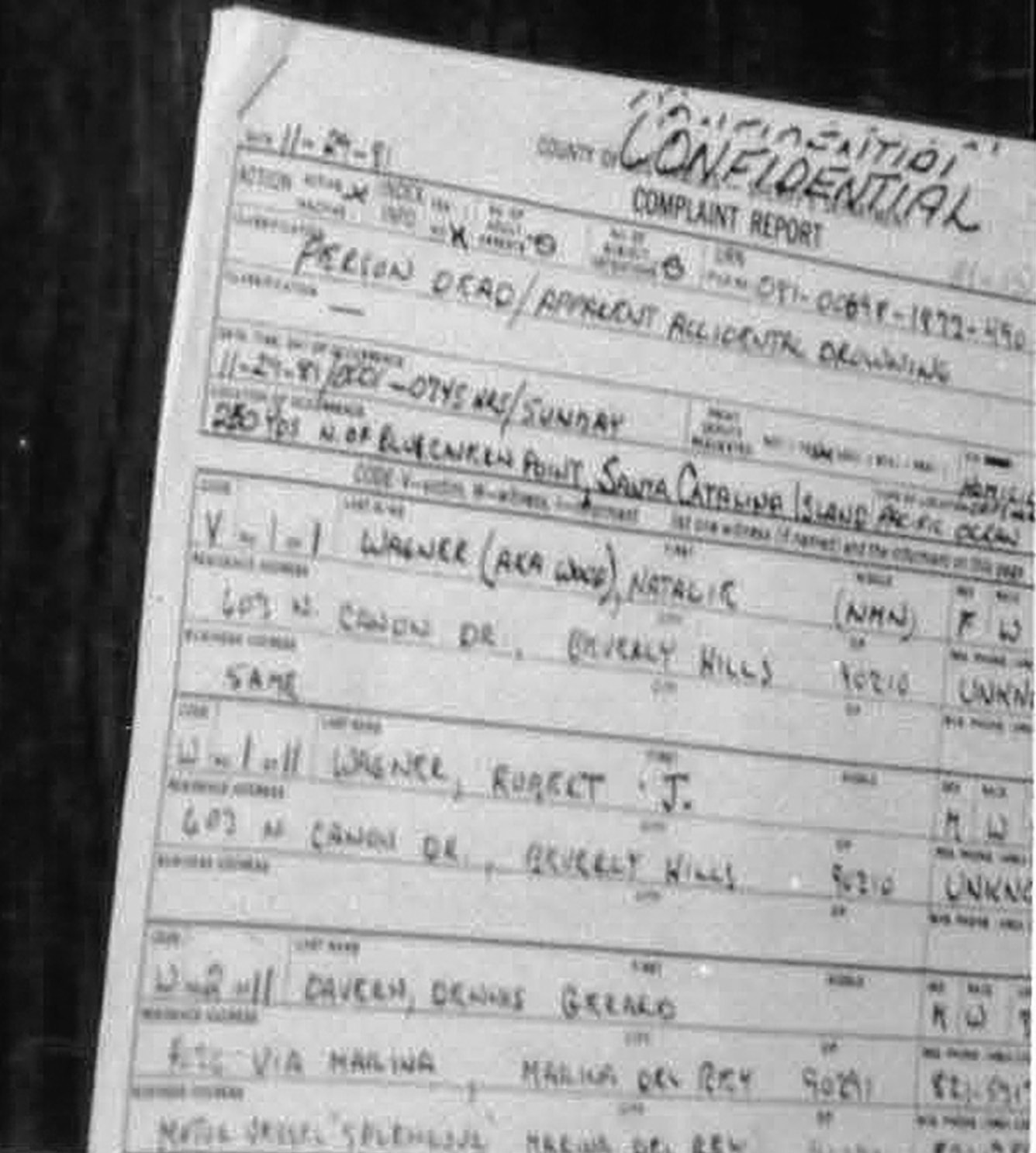

The first item I pulled from a box was a complaint report dated November 29, 1981. “CONFIDENTIAL” was handwritten at the top of every page in urgent black capitals. R. W. Kroll, a deputy in Avalon who was the first sheriff’s officer to respond to the call about Natalie Wood and the first investigator aboard the Splendour, had prepared the complaint report. He was no longer alive, I later discovered. In his report, Kroll wrote: “PERSON DEAD/APPARENT ACCIDENTAL DROWNING.” What immediately got my attention was the word apparent. Kroll, the first investigator on the scene, appeared, from his report, to question Natalie Wood’s suggested cause of death. In his complaint report, he designated it as only an “apparent” accidental drowning. He classified it as “homicide.”

Kroll, whose name I had never seen in any accounts of Natalie Wood’s death, arrived at the Splendour before six A.M., when Natalie Wood was still missing. His confidential report noted a broken wine bottle in the salon that Wagner told him must have fallen, but Wagner had smashed it as Davern would reveal in his unsettling stories to tabloids in 1985. Wagner is quoted in a 2004 biography and his 2008 memoir saying he shattered the wine bottle.

In his report, Kroll recounted his interviews with Wagner, Davern, and several other witnesses, noting the times. He had also helped to retrieve Natalie Wood’s body from the ocean at 7:44 A.M. and accompanied her body to the USC marine lab on the isthmus. Kroll wrote that he saw bruises on Natalie’s arms and legs, and that the bridge of her nose was lacerated. Kroll made a special note in his report that he stayed with Natalie Wood’s body until she was positively identified at 8:30 A.M.—by Dennis Davern. Robert Wagner had sent a deckhand to identify Natalie, the woman he said he loved so much she took his breath away.

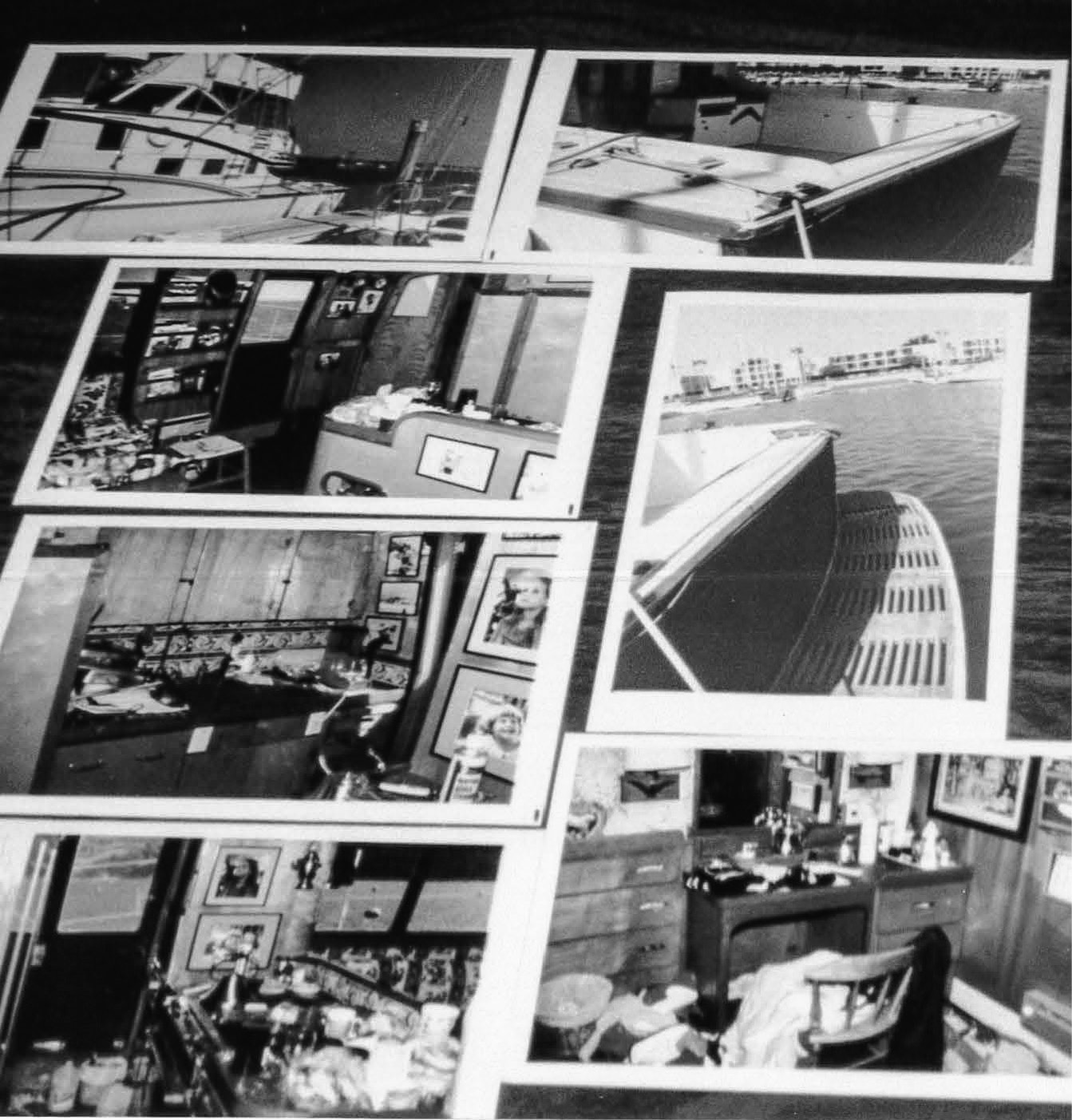

Photo from the murder book by Suzanne Finstad.

The report was spellbinding. And deeply disturbing.

Kroll’s confidential report, along with unexamined clues in the investigators’ “homicide books” (the case notes written by Rasure and his partner), including the argument between R.J. and Walken that Sinatra tried to squelch, recast the events of Natalie Wood’s mysterious last night as something more sinister than a tragic misstep by a “tipsy” Natalie, as Noguchi ruled.

Inside the same box were also color photographs, four by six inches, taken after Natalie’s body was found. Photographs of the Splendour, of a swim step, an outside deck, interior rooms. There were close-ups of trash cans holding empty liquor bottles, discarded beer cans, discarded wine bottles. A wineglass half-full. A photograph of Natalie’s vanity and dressing table showing clothes strewn everywhere, including the floor. Her purse was also on the floor. The scenes inside the Splendour, captured by a police photographer, were of chaos.

My mother, a teacher with a master’s degree in counseling, who had been quietly and carefully reviewing all the items I set aside after I documented them on my laptop, paused with a grave expression on her face; she interrupted the eerie silence in the room to exclaim, “Suzanne, this was not an accident.” It was more than an intuition. From the photos of the boat, what she had read, and what she felt, she believed that Robert Wagner was responsible for Natalie’s death, that all three men on the boat were culpable, and that they were all concealing it.

My conclusion, after I read the scant homicide notebook of Rasure’s partner Roy Hamilton, reread Rasure’s comically inept notes, and reviewed the other items in the murder book, was no less dramatic: There was no investigation of Natalie Wood’s death.

It was a sham.

The two lead detectives, as was made obvious by the murder book, had ignored potential witnesses, left leads dangling, and their interviews, what few they did, had been short and shallow. Rasure had told me that he was satisfied that Natalie Wood’s death was an accident in five days. On the fourth day, December 1, 1981, the same day as the autopsy results of accidental drowning were announced, Rasure issued a statement that he was “tying up loose ends.” According to the murder book reports, that was before he had even scheduled his follow-up interviews with Wagner, Walken, and Davern.

The lead detective’s homicide investigation of Natalie’s death was as inept as his five-minute interrogation of Robert Wagner, the key witness in a murky chain of circumstances that Rasure was too enamored by Wagner, “a famous movie star,” to dig in any deeper.

Before I left the sheriff’s office, I typed notes in my laptop for every scrap of paper in the murder book, even the scribblings on pages torn from vintage pink “While You Were Out” telephone note pads, where I found a return number and a brief message for investigators from Marilyn Wayne, who I recalled had been on a boat near the Splendour. I copied every page of Detective Roy Hamilton’s homicide notebook, Rasure’s notebook, and of course, Deputy Kroll’s confidential, unseen, and elucidating complaint report.

Clues first ignored, then embalmed in the murder book, helped me piece together a puzzle of twenty years. Using names, addresses, phone numbers, witnesses, and potential witnesses from 1981 that I gathered from the boxes provided by Sweet Lou Danoff, I followed leads the detectives hadn’t. One person was dead, but I was given the notes he made the night Natalie drowned. Another vital witness, now employed on a ship in Mexico, called me from a phone booth on shore. I found Marilyn Wayne’s son in Asia.

By the end of this odyssey, I had tracked down literally every person I could find associated with Natalie Wood’s last weekend. I interviewed the waitresses at Doug’s Harbor Reef who served Natalie, R.J., Walken, and Davern dinner and a multitude of drinks the night before she turned up dead, and they all had telling memories. Diners at nearby tables had stories too. A little girl, whose hair Natalie had braided in the bathroom, provided a key to her emotional state. Marilyn Wayne, who said that Sheriff’s investigators never followed up on her call, told me that she heard a woman crying for help that night in the ocean near the Splendour and that she heard two men mocking her. Wayne’s son, and her then-fiancé John Payne, on the boat with her that night, corroborated her recollections. The host at the restaurant who heard R.J.’s first, slurred radio call at 1:30 A.M. revealed that R.J. told him not to call anyone else to help search for Natalie, specifically not the coast guard. I discovered that the harbormaster, at 3:30 A.M., had to demand that Robert Wagner let him call the coast guard to help find Natalie. The lifeguard who pulled Natalie’s body out of the sea at 7:35 A.M. told me he could have saved her if it had been even an hour sooner. I even found the widow of Deputy Kroll, the Sheriff’s investigator from Avalon, whose initial report appeared to question whether Natalie Wood’s drowning was an accident. She remembered how troubled Kroll was when the case was closed and ruled an accident.

By threading all of this together, and more, I was able to create a virtual diary of Natalie’s last weekend in Natasha. The results were illuminating, harrowing, and deeply disillusioning.

32 AS I WAS WRITING THE final chapter of Natasha, in 2001, I got an urgent call from Lana Wood. She knew, she said, how her sister had drowned. For nine years, she had kept silent about a phone call she’d received in 1992 from R.J.’s deckhand, Dennis Davern, who was “obviously drinking.” Although Davern had provided bits and pieces of the nightmarish story of what he saw and heard on the Splendour to magazines and tabloids—bits and pieces that fit the hideous chain of facts and events of that weekend that I had uncovered and linked together—he had never revealed its ugly climax. Now he seemed compelled to tell Natalie’s sister. That year, Davern had married and become a father. He and his wife named their daughter Natasha. Natalie, it appeared, was weighing on Dennis Davern’s conscience.

Lana explained her sudden, emphatic call to me saying simply, “It’s time.” Natalie had been gone for twenty years. It was time, she said, to reveal what had really happened to her, and Lana wanted to reveal it in Natasha.

So I included Davern’s account of a volatile fight between R.J. and Natalie that he’d told Lana he’d heard, and then seen, before Natalie went off the boat. It was a fight that I already knew about from nearby boater Warren Archer’s ignored statement in the murder book that he’d heard R.J. and Natalie fighting shortly before 11 P.M. The campgrounds maintenance man, Paul Wintler, told me he’d heard about the fight from R.J. around 2 A.M. when he took R.J. ashore ostensibly to look for Natalie.

Davern told Lana in his phone call to her in 1992 that he heard a violent altercation between R.J. and Natalie in the main stateroom, directly below the bridge where he was. R.J. left the stateroom through a double-door to the rear deck, visible from the bridge. Davern told Lana that he got a glimpse of Natalie, in her nightgown on the rear deck, arguing with R.J. As the fight escalated, Natalie went overboard, Davern told Lana, and as he began to panic, R.J. told him, “Leave her there, teach her a lesson.”

Lana said that Davern told her that he saw Wagner push Natalie overboard. Since then, he has refuted that story. “Natalie came back up on deck to continue the fight with R.J.,” Lana related to me. Davern, she said, was still on the bridge, directly over the main stateroom, with a view to the rear deck. “Dennis said that it appeared to him as though R.J. shoved her away. She went overboard.”

What I did not include then was R.J.’s chilling “push” that Lana said was part of Davern’s intense, intoxicated call to her in 1992. In 2001, Davern denied the “push” to Lana and to me, saying that he did not see the actual moment that Natalie went overboard. Still, it was heart-stopping. Whether or not R.J. actually shoved Natalie off the boat, Davern’s eyewitness account as told to Lana that Wagner knew that Natalie, who couldn’t swim, was in the water, makes his refusal to let anyone look for her for two and a half hours macabre, if not second-degree murder.

Several months later, when Natasha was in galleys, an extraordinary coincidence occurred. My brother, Dr. Rick Finstad, then a dentist in Houston, telephoned me to say that a patient of his had been dating Dennis Davern at the time Natalie Wood drowned. “I asked her if he had told her anything about that evening,” he said, still dumbfounded by the strange coincidence. “At first she was reluctant to say anything. After a tiny bit of prompting she divulged some remarkable information.”

His patient, a woman I’ll call Linda Christy to protect her privacy, agreed to talk to me. Christy, an accountant, told me that in 1981, she was the office manager of Amen Wardy, a boutique in Newport Beach, where Natalie liked to shop. Christy met Dennis Davern when he accompanied Natalie to the boutique after a sail on the Splendour. “He thought the world of Natalie. He’d say, ‘Every woman should be like Natalie.’ ” Christy and Davern began to date in the summer of 1981, “whenever [they] were in each other’s orbit.” Interestingly, she said that Davern “was not a heavy drinker” on their dates.

In the days after Natalie Wood drowned, Christy got several panicked phone calls from Davern. He sounded “pretty shaken up,” she recalled, “very strange.” He was determined to deliver a message to Christy about the drowning. “He told me, ‘Don’t believe anything you read or see in print about what happened. Don’t believe anything that comes out. It’s not real.’ ” Christy said, “Everything became very hush-hush and he was very cryptic. He said, ‘Everyone’s been paid off, bribed off, threatened off. What you’re going to be seeing about this—it’s all a lie.’ ”

During this tense, dramatic call, Davern told Christy about the fight between R.J. and Natalie, just as he later described it to Lana in 1992. “Dennis told me there was a fight going on like you wouldn’t believe and R.J. was confronting her. Natalie and Walken were having an affair or something and it came to blows that night. That’s what this whole thing was about. Dennis said he was getting real scared about the fight. It got pretty out of control…there was concern about who else could be around who could be hearing this—the fight—going on. This is what I was told within a couple of days of it happening.”

Davern told Linda Christy that “he was there” when Natalie went off the boat. “Dennis knows what happened. I don’t know if he saw her go overboard. Dennis said that he was under orders from R.J. not to assist Natalie when she was in the water already.” She distinctly recalled what “bad shape” he was in. “He was scared about what’s gonna happen: Is R.J. gonna try to put this back on him? That somehow this was Dennis’s fault? He was afraid of R.J.”

Christy chose not to go to the police after Natalie drowned to report Davern’s horror story. “It was just a very strange feeling,” she said. “It felt like I was privy to information I didn’t need.”

That was the tragedy: Friends, like Sinatra, were blindly loyal to R.J.; investigators, such as Rasure, were starstruck; Davern was frightened; and the rest, people like Linda Christy, didn’t want to get involved.

No one protected Natalie Wood. Even in death.

33 ROBERT WAGNER WAS NOT AN advocate of Natasha. His early refusal to be interviewed in response to my meticulously researched biography—despite my written requests and recommendations from friends of his (including a call from former CBS president Bud Grant)—was the first hint of the threat that the truth posed to him.

Natalie Wood’s older half-sister, Olga Viripaeff, apprised me of his more devious tactics to discredit my work. Olga mentioned that the writer Gavin Lambert, a friend of R.J.’s, had called her; he’d told Olga that R.J. was paying him to write a biography of Natalie. Lambert later complained to me that he didn’t want to do the book, that it was a “favor” to R.J. Wagner’s strategy was not difficult to decipher. He could control the content of Lambert’s book to try to repudiate Natasha and no one would know that Robert Wagner was Lambert’s silent partner. The next time I phoned Olga with a follow-up question from earlier interviews, she said R.J. had “ordered” her not to talk to me.

All of this occurred before I had even started to investigate Natalie Wood’s death, when I assumed—hoped—that her drowning was a horrible accident.

A month after Natasha was published, Robert Wagner appeared on Larry King Live. King had canceled my appearance to promote the book, under pressure, I was told by a Live staff member and by my publicist, from his close friend Robert Wagner. During the interview with Wagner, King almost immediately brought up “the Natalie Wood episode,” asking his friend R.J., “What did you make of the book that came out…did you read it?” “You know, Larry, I didn’t read it,” replied Wagner. “I didn’t read the book. The woman had approached me on doing the book. I’m sorry, she did not approach me on doing the book or my representatives.”

After this contradictory falsehood, Wagner defamed me, saying, incoherently, “This book is—you know, this woman has fabricated, you know, those things that are all these things….And there’s absolutely nothing you can do about it.”

After briefly wondering how Robert Wagner knew I “fabricated” anything if he had never read my book, I hired a Beverly Hills lawyer to send Wagner’s attorney Leo Ziffren (brother of R.J.’s lawyer “fixer” Paul Ziffren) a strongly worded “cease and desist” letter; then I wrote to Larry King refuting Wagner’s defamatory statements, and I moved on.

Still, the incident disturbed me. I dedicated four years of my life to researching Natalie Wood and interviewed more than four hundred people, the majority recorded on tape, documented in forty-four pages of annotations. Based on his lawyer’s correspondence with my publisher, and comments made to me by Natalie’s sister and half-sister, Wagner seemed more obsessed with the line in Natasha in which Natalie flees the house after finding him with a man than the implications about his role in her death.

For months, I had debated whether to disclose the secret of R.J.’s affair, and if so, whether to reveal that Wagner’s lover was a man. In the end, I followed the advice of actor-director Robert Redford, Natalie’s close friend, whom I interviewed. Redford’s suggestion was that of a director: “Ask yourself, how important is it to the story you’re telling?”

By that guideline, the secret was crucial. Walking in on her husband’s affair, in their own home, nearly undid Natalie. The fact that R.J.’s lover was a man, and that Natalie actually saw them being physically intimate, was a shock that almost cost her her life and traumatized Natalie for the remainder of it. I also wanted to clear Natalie’s name from scandal over an affair with Beatty that I was certain she had never had, a scandal I believed Natalie bore to protect R.J. at a time, 1961, when an affair with a man would have damaged his career. Wagner, with his virulent denials of homosexuality in 2001, seemed, to me, like a man who doth protest too much.

About that time, I received what Natalie’s mystical Russian mother might have called “a message from the other side.”

The improbable medium, Ruby Jackman, was an elderly retired office cleaner in Central California who enjoyed reading medical journals. Ruby contacted Lana Wood that fall to tell her she might have an unpublished autobiography by Natalie Wood. In the early eighties, a celebrity diet doctor asked Ruby to help clean out his office. To thank her, he gave Ruby his old medical journals. Inside the journals were one hundred or so loose pages, both typed and handwritten, from what Ruby believed was the manuscript for Natalie’s autobiography.

Ruby had been guarding the pages for twenty years. When she heard about Natasha in 2001, Ruby decided to call Lana because she wanted to know if the manuscript she found was authentic. Lana asked me to go with her to Jackman’s trailer park to examine the pages. With such a bizarre premise, neither of us expected to find a lost autobiography by Natalie. But we decided we’d enjoy the road trip.

Lana and I sat with Ruby around a cozy colonial table, where she had laid out the pages for us to read. The typed cover page, dated July 29, 1966, was addressed to Peter Wyden from Natalie Wood. It was almost immediately obvious to both of us that Natalie had written the pages. A third of the manuscript was entirely handwritten. There was no doubt that it was Natalie’s neat, distinctive handwriting. As we randomly chose pages to read from Natalie’s memoir, Lana burst into tears. Her sister, in that moment, had come to life again in her own voice.

This suddenly discovered memoir validated all that I had written, and all that I had intuited, in Natasha. Natalie touched upon the “demons” from her past, and her fear of being alone and its origin (“As a child I had been so overprotected & insulated that being alone seemed an awful threat to me”); how, as a child, she had “always done as [she] was told”; that she had “no real identity”; that she was “terrified of flying”; her romantic illusion from childhood of R.J. as a “magical Prince Charming”; her reliance on her analyst; her deep connection to The Little Prince; that she was “scared to death” of water.

In her own handwriting, Natalie confirmed that her divorce had nothing to do with Warren Beatty. “There was gossip & speculation that Warren was in some way responsible for the end of the marriage,” she wrote. “It is totally untrue.” She even confirmed the “rift” I disclosed that they had during Splendor, writing, “between takes, Warren and I went our separate way.”

Natalie also wrote about seeing Marilyn Monroe at a birthday party days before her apparent suicide and overhearing her despair at turning thirty-six. Natalie revealed the “enormous effect” it had on her, an intuition about her I had included in Natasha. More surreally, Natalie described her feelings in almost the same words. Lana, sitting next to me, whispered, “It’s almost as if you channeled Natalie.”

After we left Ruby Jackman’s, I did further research on Natalie’s memoir, missing for thirty-five years, which had mysteriously found its way to Lana and me. There it was, referenced in The Hollywood Reporter in my files. On July 5, 1966, the trade paper reported that Ladies’ Home Journal had asked Natalie to write a “life story” that summer. Peter Wyden, the name that appeared on the first page of the memoir we read at Ruby’s house, was an executive editor for Ladies’ Home Journal at the time. I faxed a few pages of the memoir to Anthony Costello, Natalie’s personal secretary in 1966. Not only did Costello remember Natalie writing her life story by hand that summer, he had typed the pages for her.

Natalie eventually backed out, fearing that by writing candidly about psychotherapy, her fears, and other personal problems, she would reveal more than society could handle in the sixties.

In her life story, Natalie also wrote of her love-hate relationship with the sea. Dark water was her terror. But her favorite painting, she wrote, was a seascape by Courbet she had bought at a New York gallery in 1966 while filming Penelope. It was hanging in her living room, and she would put it over the mantel in the family room of the house on Canon Drive in Beverly Hills, the home that she and R.J. purchased when they remarried.

“It is a simple work showing a tiny boat in a harbor at sunset,” she wrote. “Somehow that fragile craft facing an open strange sea reminds me of The Little Prince.”

Natalie’s poignant description of her favorite painting—a tiny, fragile craft, alone in a strange sea—eerily foreshadowed her own death.

34 THE MOST VALIDATING DISCOVERY IN the memoir was Natalie’s confirmation of the secret she kept about why her marriage to R.J. ended. Natalie wrote that she “wanted to set the record straight” about why she and R.J. divorced. “I have suffered in silence from gossip about my walking away from my marriage to go with Warren….but Warren had nothing to do with it. We began our relationship after, not before, my marriage ended.” The kindhearted Natalie continued to protect R.J., alluding to but not revealing the sexual betrayal that shattered her. “It is too painful for me to recall in print the incident that led to the final break-up,” she wrote. “It was more than a final straw, it was reality crushing the fragile web of romantic fantasies with sledgehammer force.”

She was more specific in another passage, stating exactly why she related to Daisy Clover, the character she played in Inside Daisy Clover. “Daisy becomes a movie star, falls in love with a handsome actor who is attracted to other men, and she discovers this flaw on her honeymoon. After her marriage and career go haywire, Daisy finds deep inside herself a resourceful and dependable human being.” Natalie, in effect, had outed R.J.

Natalie was alluding to the traumatic night at the Beverly mansion, her intended dream house with R.J., when she said that she opened a door, to look for him, and saw R.J. intertwined with a man. Or as her mother, Maria Gurdin, told her neighbor and closest friend, Jeanne Hyatt, the next morning, “She caught him in the act.” Lana was fifteen when Natalie arrived at the house that night in June of 1961, bleeding from a crystal glass she’d crushed in her hand and nearly berserk. Lana affirmed to me what Jeanne called “that horrid thing” that Natalie had seen.

“To hear that he could be that way is one thing,” Jeanne said to me, “but to see it in action is another.” Natalie, Lana told me, shut herself in her old bedroom. Their mother found her in a coma from an overdose of sleeping pills. “The poor little thing,” recalled Jeanne Hyatt, who heard every detail from Maria, “I would still say that she was in such shock over that, that she took the pills to go to sleep, not to commit suicide. Of course, in that state she could have overdosed without even realizing it.”

I first heard about the “secret,” or the real reason Natalie divorced R.J., from Robert Hyatt, Jeanne Hyatt’s son. He and Natalie were close friends as child actors on Miracle on 34th Street. They played teenage siblings on a TV series and shared confidences, like real siblings, ever after. Their mothers, Maria and Jeanne, were best friends, neighbors, and confidantes. Hyatt told me that he learned about the secret the night it happened, at his mother’s house.

The first time he told me, Hyatt turned off my tape recorder, wrote one line on a piece of paper, and slid the paper across the table. He’d printed, “NATALIE SAW WAGNER HAVING SEX WITH THE BUTLER.” When I asked him why he wrote it on a piece of paper, Hyatt told me he was afraid that Robert Wagner would “screw him around.” The same fear that half of Hollywood, and Dennis Davern, seemed to share.

After further reassurance, Hyatt said I could turn the recorder back on. “I just put down for you why,” he told me. “That’s what happened. That is what happened. I know that.” He went on to say, “I was awakened in the middle of the night with a phone call from Natalie’s mother. And she was freaking out. She called up to tell my mother, but I answered the phone, and it was late at night, so Marie just started telling me everything. Because she had been telling me for years when Natalie married Wagner that ‘no good will come of this, it will be trouble.’ And she was right. Twice.” The secret was so deeply buried, and so traumatizing, it was several years, Lana told me, before Natalie could discuss it with her.

“Why it didn’t totally destroy her—it was close, I’ll tell you,” Natalie’s closest childhood friend, Mary Ann Brooks, confided to me. “I didn’t think she was going to pull out of it….She never got over it. Never.” Mary Ann, one of the few Natalie trusted with the secret, told me that rumors about R.J.’s bisexuality “were flying” before they married. R.J. denied them. “Oh, Mary Ann,” she recalled Natalie telling her. “All these people are just jealous of us.”

After she found R.J. with the butler, Mary Ann recalled, “She went through, ‘It’s my fault. What’s wrong with me?’ I said, ‘Honey, you have to accept now. He lied to you.’ She even tried to protect him. I told her, ‘You’ve got to face what we’re talking about here.’ Her life was just a disaster. Catastrophic levels. Her whole world went—her private world, her professional world, everything. It was just like somebody dropped a bomb.”

After I wrote Natasha, supporting details emerged. Lana recalled that the butler was named Cavendish. Hedda Hopper mentioned Cavendish by name as the butler in an article about the newlywed Wagners, three years before Natalie found him with R.J. “He brings them breakfast in bed,” wrote Hopper. The Wagners’ butler, just as Robert Hyatt described him to me, was an older, English gentleman. Hyatt said his name was David Cavendish. A syndicated columnist writing about the Wagners’ marriage in 1958 also brought up David Cavendish, describing him, ironically, as Natalie and R.J.’s “English man-about-the-house.”

Lana told me recently that Cavendish lived with R.J. in a bachelor apartment on Durant in Beverly Hills before he married Natalie. “R.J. had him living with him as his ‘valet,’ his ‘man,’ ” Hyatt told me. “Natalie was questioning why he had that guy before they got married. She was trying to get rid of him.”

I even found movie magazines from the fifties with fan-girl articles about the young Robert Wagner that include a peculiar mention of his live-in butler. For a Photoplay article in 1953, the dapper twenty-three-year-old Bob Wagner posed for staged photographs outside his “first bachelor apartment,” an elegant Colonial fourplex. Per Photoplay, Bob’s friend, actor Dan Dailey, suggested he rent the apartment below his. Dailey, an older song-and-dance man from MGM musicals of the forties, lived in a one-bedroom with his “houseboy.”

Before Natasha was published, I was asked to be a co–executive producer on what became The Mystery of Natalie Wood, a three-hour television movie directed by Peter Bogdanovich. During pre-production, the rights were assigned to Von Zerneck Sertner Films, which made devastating script changes. Robert M. Sertner, the executive producer, deleted scenes showing Wagner’s affair and inserted new scenes of Natalie flirting with Beatty in front of R.J. to cuckold him while filming Splendor in the Grass, the false rumor fabricated by the press, which Natalie ignored to protect R.J.’s image and conceal his tryst.

Other major script changes bore no resemblance to Natasha or to the truth. In the final scene, an intoxicated Natalie goes up to the deck by herself in her nightgown. She hears a wine bottle rolling in the bottom of the rubber dinghy whose sound has been keeping her awake. Not only was this a scene that didn’t happen, but, as I wrote in Natasha, it had been proven that it couldn’t have happened. In the scene that was filmed, an inebriated Natalie tries to retrieve the wine bottle, steps into the dinghy, and drunkenly falls overboard to her death.

Yet again, Hollywood betrayed Natalie Wood.

That was when I asked to withdraw. Sertner, who changed the script to make Natalie the reason her marriage to R.J. ended and the cause of her own death, was, as it happened, a friend of Robert Wagner’s.

Perhaps the most on-point validation of R.J.’s secret, post Natasha, was in my own archive, a rediscovered interview done early in my research. The interview was with Irving Brecher, a screenwriter of classic films from the golden age of Hollywood. Brecher directed Wagner in Sail a Crooked Ship, the film that R.J. was completing when Natalie said she walked in on him with the English houseman. I listened to the tape again, twenty years later.

Throughout the interview, Brecher, who told me he liked Bob Wagner and enjoyed working with him on the film, seemed preoccupied with the Wagners’ marriage in 1961 and Natalie’s apparent unhappiness. Brecher kept circling back to something that was nagging at him. “And I’m just wondering,” he said thoughtfully, “whether, for any reason, Bob was involved in any homosexuality?” I told Brecher I had heard rumors he was bisexual. “Well, I think that you may be onto something,” he said. “And I’m not accusing him, but it’s quite possible.”

Brecher measured his words carefully. “I only saw one thing,” he told me. “And I—Jesus. It’s not an awful thing I saw. But once, I did see him with another actor, in a very—in a house, and I happened to walk in the room. And they weren’t doing anything serious, but one of them was fondling the other’s butt. When I say fondling, I mean a hand in the butt.” This happened, Brecher said, around June 1961—the same month that Natalie took an overdose of sleeping pills and went into a coma.

Brecher’s account suggests that R.J. took risks with his trysts. “It was in a private house,” Brecher recalled. “They were guests in the house for a few minutes on the way out to dinner.” The actor who was fondling or being fondled by Wagner was “reasonably” well-known, Brecher said, “but I’m not gonna mention it. Nothing was made of it, [so] there was no embarrassment.”

Still, the image had lingered in Brecher’s mind since 1961. Just as it had in Natalie’s.

As Robert Redford asked, how important is this to the story being told? Robert Wagner’s sexual betrayal of Natalie in their first marriage is the dark cloud that looms over the story of a long weekend that began with Natalie’s using Walken to provoke an already jealous, angry R.J. and ended with Natalie in the sea with no one to save her.

In a 2008 memoir, Pieces of My Heart, Robert Wagner revealed a violent, frightening dark side that was spinning out of control when he was in an earlier jealous love triangle over Natalie. Like Walken, R.J.’s 1961 rival was Natalie’s costar, a younger, more successful actor. She was separated from Wagner, devastated by his affair with a man, but she had not filed for divorce. “Then Warren came into the picture,” Wagner angrily recalled. “That summer, when I read about them as the hot young couple around town, I wanted to kill that son of a bitch. Life magazine was calling Beatty ‘the most exciting American male in movies.’ My last four or five pictures had been flops. I was hanging around outside his house with a gun, hoping he would walk out. I not only wanted to kill him, I was prepared to kill him. Everything was coming to an end—my marriage, my career, the life I had built. I remember thinking that if I couldn’t kill Beatty, maybe I should kill myself. It was either flip out or flip the page: I chose the latter.”

The parallels in 1961 to the night on the Splendour in 1981 were eerie. Wagner had been hearing gossip from the Brainstorm set that Natalie was having an affair with Walken. Walken was Hollywood’s new, brash leading man in 1981, an Academy Award winner two years earlier for The Deer Hunter. Wagner “sold soap,” as he derisively described his TV career. R.J.’s visceral response to that dynamic in 1961 had been to kill the rival who was threatening “the life [he] had built.”

More recently, Wagner offered an even more disturbing insight into his psyche. In a long video interview in 2011 with Alan K. Rode, the host of an annual Palm Springs film festival, he said that his favorite role was in the 1956 film noir A Kiss Before Dying. In the movie’s most famous scene, Wagner’s character, Bud, who has discovered his pregnant fiancé might be disinherited, lures her to the roof of a building, pushes her to her death, and tries to make it look like suicide.

The movie poster is of a young Robert Wagner as he pushes Joanne Woodward off a building. The poster was released July 20, 1956, the day of Natalie Wood’s first date with Robert Wagner, which was also Natalie’s eighteenth birthday.

Wagner first heard about the story three years earlier from his sister, who read it in a magazine. She told R.J. that he reminded her of Bud, a character described as a charming, amoral sociopath who would stop at nothing to get ahead. “That character, I never thought of him as a villain, really,” Wagner said in his strangely candid 2011 interview with Rode. “I mean, he was just tryin’ to keep it goin’, to get ahead. I never played him as a guy who was a killer or anything like that. He was in love with her and it was just too much pressure for him. I mean, he only had one way to get out.” R.J., then twenty-three and under contract to Fox, was so obsessed with playing Bud, he persuaded studio chief Darryl Zanuck to buy the film rights for him before the book was published and took it to producer Robert Jacks himself to set it up.

The film was notable for another reason. The dark, suave Robert Quarry, who would become a cult figure in the 1970s for his seductive film portrayals of the vampire Count Yorga, played one of Bud’s victims. Quarry, a distinguished stage actor, was several years older than Wagner. “R.J. was such a pretty boy that it was hard to take him seriously in those days,” Quarry said after a screening of A Kiss Before Dying, at the height of his fame as Count Yorga. In his last years, Quarry, who was gay, shared confidences with Tim Sullivan, a writer-producer-director-journalist who interviewed and befriended him. Quarry told Sullivan, “Everyone knew Wagner was a hypocrite. He’d play the dreamy straight boy for the teenage girls.” Quarry recalled to Sullivan how R.J. would stroll off the set, put his arm around whichever young actress the studio was promoting as his girlfriend, and pose for photographers like a man in love.

By the end of filming on A Kiss Before Dying, the actress would be Natalie Wood.

35 NATALIE WOOD’S DROWNING IS NO longer presumed to be an accident. The evidentiary timeline in Natasha—a harrowing, irrefutable account of Natalie’s last weekend, with almost minute-by-minute detail of her last night, assembled from buried evidence in the murder book, untapped leads, ignored witnesses, and the brief, strange, contradictory police statements of the three men on the Splendour—creates an unsavory portrait of the three others with her on the boat when she drowned.

No matter how Natalie got into the water, my research made clear to me and to Sheriff’s investigators I spoke with that Wagner’s subsequent behavior directly led to her death. Wagner’s edict to wait two and a half hours to look for her and four and a half hours to call the Coast Guard when he knew that Natalie was missing from the boat, that she could barely swim, and that she was terrified of dark water, in itself, is damning. “Wagner should have been held responsible a long time ago,” Kevin Lowe said to me a few years ago. In 2011, Lowe, a rangy, tell-it-like-it-is homicide veteran, was appointed lead investigator in the L.A. Sheriff’s Department’s much-publicized new investigation of Wood’s 1981 death. If the statute of limitations had not expired, Lowe said, Wagner would be arrested for manslaughter.

Now the only crime he can be prosecuted for is murder.

Wagner’s fate turns on Dennis Davern, the fidgety, erratic, and deeply damaged deckhand—the only apparent witness to a nightmare. As even his promoter and friend Marti Rulli observed to Lana in the nineties, “Dennis was the answer: drunken, lost, searching-for-answers-himself Dennis!” As a witness, Davern is as problematic now as when I wrote Natasha, for the same reasons: his credibility is tainted by a profit motive, differing stories, and evasion. So is Rulli’s.

Since 1985, Davern and Rulli had been trying to sell Davern’s dark, devastating story of Natalie’s last hours on the Splendour. After Natasha was published, Lana Wood and I urged Davern to go to authorities with his side of the story nine years after his drunken, soul-baring call to Lana. In his tentative way, Davern confirmed the gist of what Lana said he’d told her in 1992: that Natalie went overboard on the rear deck during a fight with R.J., that she was in the water, “and R.J. did nothing to pull her out. To teach her a lesson. And left her there to drown.”

During this call in 2001, Lana told Davern that this was his chance to clear things up, to say, “I know I was a witness, I should have done something, but I was frozen with fear.” Davern did not refute her, adding, “And saturated with Scotch.” “Yeah, and R.J. too,” replied Lana. “And you were with your boss. It was up to him to tell you what to do.” During the call, Lana begged Davern to tell investigators the truth about how Natalie drowned. “Not for money or fame, but because you care about her, that it’s been on your conscience…it would be an unburdening for you. That’s why I told Suzanne what you told me. I don’t want to cover it up anymore. I’m sick of it.” “Yeah,” agreed Davern, “you’re her sister.”

Instead, the mercurial Davern and his dogged co-writer Rulli reversed the admission he’d just made on the call and denied to Lana that he’d ever said he saw Natalie in the water or that R.J. had told him to leave her there. “The way I feel, to make things short and to the point—I’ve been wanting to do a book myself,” said Davern. “Guess I don’t know the right people.”

Davern and Rulli had a second reason to deny he’d said that he’d seen Natalie in the water or that R.J. had ordered him not to save her. The same reason he needed to retract R.J.’s murderous “shove.” Rulli had intimated it to me: “The details I have of exactly what Robert Wagner did would either put me or he in jail.” To tell Natalie’s sister that he saw R.J. shove Natalie overboard may have felt to Davern like the right thing to do in 1992, but giving that detail to the police was more problematic. “He told me he was worried about being considered an ‘accomplice,’ ” Lana wrote in an email to Marti in 2002.

In 1992, the year that Davern first called Lana, Davern and Rulli went on Now It Can Be Told to promote their hoped-for tell-all. When they thought the cameras were off, they debated, sotto voce, whether Davern should reveal “the push” on the air. “They were yelling and screaming at each other to get off the boat,” Davern says to Rulli. “Oh god, I don’t know whether I can tell them that or not.” She responds, “We have to say how she got in the water, Den, saying it right, but saying it to protect ourselves too.” “See, I don’t want to. He pushed her in.” Davern balks, saying, “I don’t wanna tell them.” Rulli leans in closer and says, “Don’t you tell them how she got into the water. We put that in the book and we’ll make billions from it.”

By 2009, Rulli had written a book about Davern’s life on the Splendour, which included Davern’s story of Natalie’s last night with enough sizzle to sell but without putting Davern at risk criminally by excluding the “bits and pieces” on how Natalie got in the water or how Davern followed R.J.’s orders not to get her out. After the book was published, Rulli used her marketing skills to publicize a petition to the L.A. Sheriff’s Department to reopen the investigation into Natalie Wood’s death because of the “new information” in a sworn statement by Davern—the statement Davern had withheld from the police so he could get a book deal. To give their petition and thereby their book maximum publicity, Rulli released the petition with Davern’s statement attached on the thirtieth anniversary of Natalie Wood’s death in 2011.

Rulli’s evidence in her petition to reopen the case consisted of Davern’s revised sworn statement and several pages of factual material that was first published in Natasha, including statements from Rulli, Marilyn Wayne, lifeguard Roger Smith, and Lana Wood, who referenced the timeline in Natasha.

The L.A. Sheriff’s Department officially reopened the investigation of Natalie Wood’s drowning in November 2011.

The two new lead investigators, Kevin Lowe and his congenial partner, Ralph Hernandez, met with me at my home a few weeks later to discuss their investigation and my findings. Both carried dog-eared copies of my book, with pages marked and lines highlighted. They told me that Natasha was the primer for the new inquiry into Natalie Wood’s death. The timeline that I had prepared was their blueprint for the byzantine events of Natalie’s last weekend. The two detectives asked to hear taped interviews I’d done since some of the key witnesses were no longer alive, including Dr. Choi, who conducted Natalie Wood’s autopsy. The notes I made of the original case file may be the only existing evidence left: The murder book, mysteriously, has since, I was told, gone missing.

Both Lowe and Hernandez have returned to listen to additional interview tapes, and they’ve requested more transcripts. When I asked what they thought of the original investigation by Rasure, Lowe said dryly, “What investigation?” Sometime after, I persuaded Linda Christy to give her critical statement to them about Davern’s phone calls a day or two after Natalie drowned. Since then, I’ve continued to discover new witnesses and direct them to Lowe and Hernandez, who stay in intermittent contact.

Christopher Walken was the first person to lawyer up after the case was reopened, and he has now spoken to the two new lead detectives. The only person on the Splendour that night who refuses to cooperate is Robert Wagner, the last person to see Natalie alive. Wagner’s only conversations with investigators about his wife’s drowning took place in 1981—the five minutes he spoke to Rasure the morning that Natalie’s body was found and their brief conversation a week or so later in Wagner’s bedroom, with Wagner in his bed, in his pajamas. Yet Wagner and his lawyers continue to issue public statements that Wagner is cooperating fully in the investigation of Natalie’s death and that he’s spoken to investigators.

“He’s a lying sack of shit,” Kevin Lowe said to me about Wagner, a year or so into the new investigation. Both Lowe and Hernandez would like to arrest Robert Wagner. The problem, they both say, is getting corroboration for Davern, the best and worst part of their case. In his sworn statement, Davern stopped short of telling Lowe and Hernandez what he confided to Linda Christy and Lana, the critical “push” by Wagner and R.J.’s orders to leave Natalie in the water. Although Davern hasn’t given police the more complete and incriminating story, Lowe and Hernandez are satisfied with the consistencies in his accounts of the fight on deck and other details.

In February of 2012, I sent Kevin Lowe an email asking, “Is there, by the way, an official ruling called ‘Death by Suspicious Circumstances’? If so, could Natalie’s death be ruled as such?” Five months later, in July, the Los Angeles coroner Dr. Lakshmanan Sathyavagiswaran issued a press release stating that he had changed the official cause of death on Natalie Wood’s death certificate from “Accidental Drowning” to “Drowning and Other Undetermined Factors” (emphasis mine). The decision to change a legendary movie star’s cause of death thirty years later was unprecedented.

The urgency I’d felt to finish Natasha had served its purpose.

When the coroner made public his supplemental report in 2013, Lowe shared with me his interpretation of the coroner’s findings, which had a Hitchcock twist. In his report, the coroner stated that he believed that Natalie Wood was unconscious when she entered the water, that she did not enter the water of her own volition, and that it was “unplanned.” In short, Lowe told me, Natalie Wood was “pushed.” The new coroner also remarked on the multiple bruises on her body, ignored in the previous autopsy report. He determined they were inflicted before Natalie entered the water. Ralph Hernandez said she looked like the victim of an assault.

The new coroner’s revised autopsy report raises the possibility that Natalie may have been struck unconscious on the boat and tossed overboard. If she was unconscious when she went into the ocean, the icy water may have revived Natalie, raising the grim possibility that she came back to consciousness as she was submerged in dark water, the terrifying death she had long feared.

Lowe told me the coroner’s new findings are “ballsy,” and “damaging” to Robert Wagner. “He said it was the right thing to do, as a man, and a doctor, and medical examiner.”

As for the hours that R.J. waited before calling for help and his misleading guidance to the two amateurs he had looking for Natalie at 1:30 A.M., Lowe said, “Obviously, Wagner didn’t want to find her.”

In 2013, R.J. began what was thought to be a second memoir to respond to the damning new findings that led to the change in Natalie’s official cause of death. R.J.’s tome, instead, was You Must Remember This: Life and Style in Hollywood’s Golden Age, more of the Old Hollywood anecdotes Wagner lived to tell.

What Wagner refuses to talk about, at least to investigators, is his wife Natalie’s death.

“Well, I already had, there wasn’t anything left to say,” he remarked to his pal Larry King on a 2014 tour to promote his new Hollywood book on Larry King Live. “When that accident happened, there were so many people on top of that, you know, at the time, you can’t believe it.”

Wagner’s only response was to smirk to a question from King about “the skipper,” Davern, who had given a long, unsettling interview on 48 Hours describing the violent fight between Natalie and R.J. he witnessed on the deck just before Natalie went overboard and drowned. “Well…he was rather transparent, you know?” R.J. told Larry King with a look of amusement. “He was rather transparent. I hadn’t seen him for a long time. And, you know, he wasn’t the captain of the boat, you know?”

In February of 2018, frustrated by the stalemate with Wagner, the Sheriff’s Department decided to try another tactic to impel him to talk. This time, the LASD held a news conference to update the public on the reopened investigation. John Corina, the spokesperson for Lowe and Hernandez, stated, “The original story that’s been told—that Wood took a dinghy into town and fell into the water—doesn’t add up. There was a rainstorm and rough waters the night Wood disappeared. She was one of four people on a large boat when she went into the water, but we believe he was alone with her on one part of the vessel.”

Natalie’s drowning, Corina announced, was now considered to be “a suspicious death.” Robert Wagner was named an official “Person of Interest.” Asked why, Corina seemed irritated. “Because he was the last one with Natalie Wood,” Corina responded, “and somehow she ends up in the water and drowns.”

He also referred to Wagner’s peculiar actions after Natalie went missing, the string of oddities I had painstakingly reconstructed in my book. “Some of the things we found that [Wagner] did afterwards, or didn’t do, in the boat, cause us to say, ‘This doesn’t make any sense,’ ” Corina said. “We’re at the end of the investigation. We’re at a standstill, so we thought we’d give it one more shot to the public.”

If Corina had hoped to smoke out Robert Wagner, he was disappointed.

R.J.’s only comment on Natalie’s whereabouts that night is in his 2008 memoir: “The last time I saw my wife she was fixing her hair at a little vanity in the bathroom while I was arguing with Chris Walken. I saw her shut the door. She was going to bed.”

Recently, I’ve found three new witnesses. One is a confidential source that I put in touch with Ralph Hernandez. The source had information that Christopher Walken said he heard the fight between R.J. and Natalie and that he told a friend not long after Natalie drowned that Wagner pushed her. Lana asked Lowe and Hernandez once about Walken’s new statement. “Ralph said the only way Chris’d talk to them is if it was never disclosed. After they spoke with him, they told me they had enough to charge R.J. So…”

The other two new witnesses were present at Natalie Wood’s autopsy. Vidal Herrera, whom I learned about from a documentary producer, took photographs of Natalie’s body for the Coroner’s Office. Herrera told us he observed significant wounds to Natalie’s head. Ralph Hernandez, who took his sworn statement, has seen the original photos and concurs that Natalie’s head wounds are “troubling.” Head wounds that may indicate that she was in a violent fight, and was pushed, or tossed, in the water while unconscious.

Because Davern omitted from his statement to police the “push” by Wagner that he and Rulli both acknowledged when they thought they were off-camera, Hernandez still lacks a witness to establish how Natalie got in the water or, in effect, who put her there. With that witness, the District Attorney’s office might agree to take the case against Wagner to a grand jury. According to Lana, the District Attorney told her that she wants a “smoking gun.”

Dr. Michael Franco may be able to provide a missing link. Franco, a family medicine specialist in Los Angeles, was an intern at the L.A. Coroner’s Office when Natalie Wood’s body was flown to Los Angeles County/USC Medical Center from Catalina. As a volunteer intern in 1981, he wasn’t listed as a coroner’s employee and therefore would not have been questioned. Franco observed what he is certain is critical physical evidence on Natalie’s body that establishes her death was a homicide.

For forty years, Franco has kept silent, not wanting to be pulled into a media circus. After decades of reflection, and my persuasion, he decided that coming forward was “the right thing to do.”

What Franco observed, and found suspicious, were the bruises on Natalie’s anterior thighs and shins, bruises he describes as “friction burns.” He told me what struck him as wrong: “I remember the striations were in the opposite direction of somebody trying to get onto a boat. It was almost like somebody being pushed off. And because of the significant amount of the bruising in the lower anterior thighs and shins, that’s what caught my attention. She would have had to have been pushed forcefully off, or there was a force that was pulling her off, or something. The amount of noticeable bruising to the thigh shouldn’t have been there.”

Franco took it up with Dr. Noguchi. “I mentioned to him the abrasions on Natalie. I told him I was having trouble understanding them. I said that they seemed to be in the opposite direction of what one would expect as to her cause of death. I remember when I told him who I was, he hesitantly stopped doing what he was doing, looked up at me, nodded his head, didn’t say anything, and then he continued doing what he’d been doing.

“What he said was, ‘Some things are best left unsaid.’ ”

Noguchi’s admission momentarily confused Franco: “I wasn’t sure what that meant initially, so, I stood there.” Noguchi, he came to believe, was acknowledging a cover-up in the Coroner’s Office. “However it was written up, that’s all you need to know,” Noguchi went on to say, according to Franco. Franco stood there, staring at him. “Again, he had his head down and wasn’t looking at me and he wasn’t saying anything. And I thought, This is my cue to step back. So, I played with that for the rest of my life.”

Ralph Hernandez wants to meet with Franco. “The Coroner botched the autopsy. For what reason I can’t prove why, but…” Hernandez continued, “We’ve got photos of her body and the bruises. We know they took tissue samples….The real question is why did they ignore them?”

Now Franco is ready to share what he saw with Hernandez. “Scientifically, with what I knew then, observed then, and intellectually looking at it…it just did not follow the water trail. There was just no reason why she would’ve had those abrasions in the direction they were. It would make sense that someone was pushing her down and wouldn’t let her stay on. The abrasions that stuck in my mind were on her anterior thighs and shins and anterior ankles. Friction burns. That observation is what I have to bring to the table.”

Franco “didn’t buy” the coroner’s cause of death. “Natalie Wood’s death wasn’t an accident. Somebody pushed her. I wasn’t following the case, so I didn’t know who all the players were. I wasn’t playing detective. I wasn’t interested in all that information. All I knew was what I saw. I knew this wasn’t a simple drowning. She had some abrasions that I could come to the conclusion that she was pushed off of whatever it was she was holding on to. There’s no reason to have those unless you’re being pushed off a surface. And they were deeper than just a simple slip-off because there is some back and forth.”

There’s another possibility. What if Wagner dropped the dinghy to make it look like Natalie had gone ashore, which was the story he gave to police? Davern said he heard the dinghy being dropped into the water after the horrible fight he’d overheard on the rear deck and that he saw R.J. somewhere near the dinghy. The next time Davern saw him, he was sweating, looked like he’d been in a struggle, and said the dinghy was gone.

The last words that Davern heard him say to Natalie were, “Get off my fucking boat!” In his revised police statement, Davern says that R.J. refused to let him turn on searchlights to look for Natalie.

The striations that Franco saw on her body at the autopsy are consistent with the possibility that Natalie tried to hoist herself onto the dinghy from the water. “Someone,” Franco says, “was pushing her down and wouldn’t let her stay on.”

Franco believes that the L.A. Coroner’s Office covered up the true cause of Natalie Wood’s death. “Whatever they decided wasn’t going to be questioned.”

Allan Abbott, of Abbott & Hast Mortuary, handled transportation for Westwood Mortuary, the morticians who embalmed Natalie Wood’s body. He bore witness, literally, to a cover-up, reported in his 2016 book. “Natalie,” Abbott wrote, “was dressed in a huge fur coat, and was covered in bruises from where she had ‘hit the rocks’…they chose the coat so the bruising wouldn’t be visible with an open casket.”

Lana Wood now refers to Natalie’s death as “a murder.” She seethes thinking about Guy McElwaine, the powerful Hollywood agent who represented her sister. A few days after Natalie drowned, McElwaine dropped by to see Lana. He’d just been to R.J.’s house, and said that R.J. told him what happened that night on the boat. “I would tell you, but I don’t trust you,” McElwaine told Lana. “What do you mean?” she asked. “Well,” replied McElwaine, “someday you’re gonna say something, and I don’t want R.J. hurt. Nobody needs to be hurt anymore.”

What about Natalie? In the memoir she began but ultimately deemed too revealing to publish, Natalie wrote, “Daisy Clover faced every major crisis alone. There was nobody to pull her out of trouble. I felt there was a lot of me in Daisy.”

Natalie had no one to protect her, in life or in death, and struggled alone in the dark sea, like the tiny, brave sailboat in her favorite painting, living out her worst nightmare, with no one responding to her calls for help.

All three men on the boat with Natalie Wood that night should be held accountable for her drowning. She went off the Splendour after a fight with R.J. so heated that it could be heard on other boats, yet hours passed before anyone with Natalie called for help. That chilling fact, and their silence afterward, twines Wagner, Davern, and Walken in a Chekhovian tragedy with no resolution short of a confession.