Chapter 11 Evacuate, evacuate!

“The fire centre is evacuating …” The Cariboo Fire Centre’s radio dispatcher broadcast the news at 3:00 p.m. on July 7. Trevor Briggs and his Blackwater Unit of firefighters based in Quesnel heard the report as they were on their way to Williams Lake to help the local fire department. Coming south on Highway 97 had been apocalyptic. Trevor wrote, “After driving by the Green Mountain fire, we saw multiple lightning strikes—all of which were instantly turning into smoke columns due to severe fire weather, some of which merged together as we drove by. Nearing McLeese Lake, halfway to our destination, we could see clearly out west toward Nazko and the Chilcotin, and it was just a scene of massive smoke column after massive smoke column. At this point, we knew it was going to be a long summer and a crazy few days ahead for us and the affected communities.”37

Fire and ice. That’s the story of lightning, according to “fulminologists,” who study the subject. Collisions between ice crystals in the middle of a storm cloud create friction, which in turn produces electrical charges. Lighter particles rise to the top of the cloud and acquire a positive charge while heavier ones sink to the bottom and become negatively charged. The electrical charges keep building until a giant spark—lightning—occurs. The amount of energy released from the rubbing of these ice crystals is astonishing. In a fraction of a second, lightning heats the air around it to 30,000°C—five times hotter than the surface of the sun. When it hits a tree, it can cause the water in the cells beneath the bark to boil instantly and explode. On July 7, thousands of lightning bolts struck the Cariboo and Chilcotin, discharging billions of joules of energy. No wonder flames erupted all over in the tinder-dry forests and grasslands. (It was so arid that some cowboys in the Chilcotin removed their horses’ shoes, for fear they would strike a rock and emit sparks.)

Several fires were burning in and around Williams Lake when Trevor arrived: at Spokin Lake to the east, at 150 Mile House to the south and in the north near the community of Wildwood and Williams Lake Airport. A pine-beetle-ravaged forest around the airport was ablaze and threatening the Cariboo Fire Centre. This was a $7 million building38 just commissioned in March 2017. Jessica Mack, a spokesperson for the centre, told me in an email that twenty-five staff members, whose jurisdiction covered 10.3 million hectares,39 had all been ordered to leave. Also at risk on the tarmac and waiting to be deployed were six helicopters out of thirty that the centre had hired for operations, as well as a “bird dog” for air traffic control and two air tankers for dropping fire retardant. Bird dog planes are used to guide the flight of the water bombers and direct them where to drop their payloads, performing an essential coordination function, like the air traffic controllers at an airport.

Trevor and his unit were first sent to work around Wildwood. In total, twenty-seven firefighters were on the ground either there or at the airport. In the evening, Trevor and his group were called to conduct a controlled burn around the airport. Conditions were good; the winds had calmed down. While an operator in a dozer was creating a fireguard, Trevor helped by conducting planned ignitions. He worked until the early morning, when half of the crew at the airport, including him, were allowed to catch a few hours of sleep. The other half continued to extend the fireguard.

When day dawned, Trevor and the firefighters who had been allowed to rest returned to the airport to relieve their colleagues. “The guard line was nicely done,” Trevor wrote. But there was a problem with the berm, a ridge of dirt built to help control the spread of rolling embers. On one side of the firebreak was green, unburned land; on the other, burned or partially burned ground. The berm was on the scorched side instead of on the green side. After that was fixed, the crew increased the size of the buffer by spraying the green land with water and by burning off the remaining fuel on the other side. These operations were successful enough to allow the staff at the fire centre to return to work. The fire overran a section of runway at the northern end of the airport and two hangars were destroyed, but none of the aircraft were damaged—they survived to fight another day.

But the Sugar Cane fire to the southeast of Williams Lake and the Wildwood fire to the northeast were still burning. They were approaching each other in a pincer-like action. At 2:00 p.m. on July 9, an evacuation order was issued for Fox Mountain and the Soda Creek area. The Sugar Cane fire was just two kilometres away from Brian McNaughton’s house. He lives on Fox Mountain about ten minutes north of the city and is the general manager of the Federation of BC Woodlot Associations. Knowledgeable about forests and fires, he was vividly aware of the hazards near his own house. He told me, “Across the street, there was a lot of dead material. The understorey had been killed by spruce budworm seven or eight years before. For some reason we have copious amounts of green lichen. So we had the makings of ladder fuels and a holocaust.” Brian and his wife left their house and went to stay at his sister’s place in Williams Lake.

The Wildwood and Sugar Cane fires merged. That blaze and another one, the White Lake fire to the northwest of Williams Lake, were growing aggressively. On July 10 at 6:22 p.m., a city-wide evacuation alert was issued for Williams Lake. Walt Cobb, serving his ninth year as mayor, was monitoring the situation closely. To add to his difficulties, Williams Lake had more people in town than it normally would. Two evacuation centres, one set up by the Cariboo Regional District and one organized by the town itself, had welcomed evacuees from 100 Mile and from the fires to the west in the Chilcotin. Fortunately, the horses being sheltered on the stampede grounds were already being moved out.

To prepare for the possibility that everyone might have to leave Williams Lake, Walt said, “We evacuated the elderly and anybody with respiratory issues.” The hospital took its patients out, most of them to Prince George. And the RCMP sent 175 more officers to Williams Lake in case the extra police presence was needed. Walt recalled, “We had the community divided into twelve different sections so that if in fact we needed to evacuate we wouldn’t create a traffic jam. We had muster points for people who couldn’t drive or didn’t have vehicles. The plan was for everyone to go north on Highway 97 to Prince George.”

By July 15, the White Lake fire to the northwest of Williams Lake had burgeoned to thirty-eight hundred hectares. About 3:30 in the afternoon, Walt got a message from the fire centre to be prepared because the fire had jumped the Fraser River at the Rudy Johnson Bridge. He recalled, “We watched it for a bit and then it started moving toward Williams Lake at about forty klicks. So it was coming fast. We got the word: ‘Evacuate, evacuate.’” At 4:59 p.m., Walt signed the papers ordering an evacuation of the town.40 “We phoned the buses, told them to go to the muster stations, phoned the RCMP, told them to get everything lined up, and start getting ready to direct traffic.”

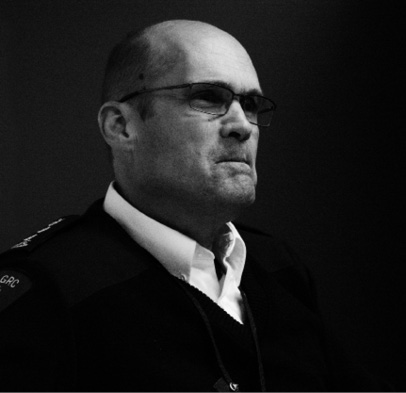

Superintendent Michel Legault was doing a tour in Williams Lake as an RCMP Bronze Commander. Later I spoke to him in Chilliwack, where he was the Officer in Charge, Pacific Region Training Centre. A brawny, dark-haired man with a moustache and a Québécois accent, he said, “The first part of the evacuation went really well. The challenge was we had a planned escape route north, and when the evacuation order was given, the north highway was cut off by fire. So now we had to switch all of our thought processes.” Evacuees had to go south to 100 Mile House, then east along Highway 24 to Little Fort, and then south again on Highway 5, where they could register at the Sandman evacuation centre in Kamloops. But this meant the evacuees would have to pass through the evacuation zone around 100 Mile House. Michel said, “We were putting people in an area where we were not supposed to send them, in a sense, so we needed to make sure that all of our area that was under order was well guarded. We didn’t want people to say, ‘I’m just going to turn here, park, wait this out.’ We couldn’t do that. So we deployed along the south highway. We monitored the traffic and we had people on Highway 24. We had people all the way down, midway to Highway 5, because we needed to tell them to go south to Kamloops, not north to Prince George.”

At 5:30 p.m., Michel called Staff Sergeant Svend Nielsen at the detachment in 100 Mile House and said, “Williams Lake is being evacuated.”

“Which way are they going?” Svend asked.

“They’re going to be in your area in forty-five minutes.”

“All righty then.”

Svend told his officers to drop everything they were doing. “We have forty-five minutes to close down the area and make sure no one stops anywhere.” Svend was able to get some help. Michel had asked his superior, Chief Superintendent Dave Attfield, for assistance and he had been able to secure the K Division Tactical Unit from Alberta with forty officers and a dozen vehicles. These officers, who are specially trained to deal with a variety of emergency situations, had arrived in the region on July 13 and were able to help patrol the exit route.

The evacuation of Williams Lake had ripple effects across the Interior of BC. In the tiny hamlet of Little Fort, Pam Jim, who together with her husband, Kam, owns Jim’s Food Market, was also notified about what was happening. “We got a call from emergency services telling us that Williams Lake was being evacuated and asking us if we could remain open,” she said. “We made the decision to stay open twenty-four hours because there were five thousand people coming down.”

Brian McNaughton and his wife, who had previously gone to Williams Lake for safety, were evacuated for a second time. “We were originally told the highway was only going to open north so I made some contact with friends up north and said, ‘We’ll see you in a few hours,’ and then we were told that they couldn’t open that route. We had to go south. So we cancelled those plans and I called my niece and said, ‘Guess what? I’m coming for a visit—and bringing some in-laws.’” In two cars, Brian and his wife, together with his sister and her husband, followed the long, slow queue going out of Williams Lake. They were headed for Kamloops.

At 6:15 p.m., Svend (wearing what he called his “ritual shorts and t-shirt”) and the officer in charge of the tactical unit from Alberta stopped the first vehicle that approached the detachment office. They explained to the driver that he had to wait a few minutes before proceeding along Highway 97 because a tactical team was coming to make sure that everyone got safely through to Highway 5 and out. Moments later the team arrived, got ahead of the evacuees in their vehicles and soon that lengthy line began snaking forward again.

Back in Williams Lake, Michel got a call from the BC Wildfire Service at 7:30, telling him that it was now safe for vehicles to go north. The window lasted about two hours and it allowed the RCMP to divert traffic to Prince George, taking some of the pressure off the southern escape route. At 9:30, Michel, who had more or less been pinned to his desk in the command centre in the basement of the Williams Lake City Hall since the evacuation order had been issued, decided he needed a breath of fresh air. This would be metaphorical fresh air, since it was still smoky outside. When he emerged into the parking lot and looked north, the deep red glow in the sky disturbed him.

There were several sawmills at the northern edge of Williams Lake, and Michel had heard worst-case scenarios. If the log piles caught, a firestorm that generated its own wind could pick up embers and burning debris and blow them onto the town. If that happened, no one could stop the inferno. Williams Lake could not be saved. The two largest mills and those of most concern were West Fraser Timber and Tolko Industries. Lying between them and the White Lake fire were three breaks: the first guard was one kilometre north of the mills, the second was at the three-kilometre mark and the third at the five-kilometre mark. Just over a kilometre south of a smaller mill was Columeetza Secondary School, which the RCMP was using to house the 175 officers who had come from out of town to work in Williams Lake. Since the wind was from the northwest, this put the school in the line of fire. Michel sent a couple of officers to look at the mills and see how many logs were stacked up in the yards. He wanted to know how much of a risk he was facing. “You’ve got about six thousand logs,” they reported back. That’s not possible, he thought. Having seen the mills, he was expecting a much larger number. He sent his officers to look again. But this time he asked a younger staff member, who was from Williams Lake and familiar with the local geography, to go along. The second report was more in line with what Michel was thinking: sixty-six thousand logs. There were thirty thousand at each of the two largest mills and six thousand at a smaller one. He also learned that thirty fire engines were hosing down the logs. But instead of alleviating his anxiety, this information only emphasized how serious the danger was. (Later, when I visited Williams Lake to do some research, I was stunned by the size of the log piles at the north end of town. I had never seen so much cut timber in my life. Some of the piles were ten metres high, twelve rows deep and a city block long. I could see why Michel would have been concerned.)

Michel phoned Glen Burgess, the fire official I’d met in Kamloops. He did tours as an incident commander in several places and at this point was in Williams Lake.

“Where are all your firefighters sleeping?” he asked.

“They’re at the airport,”

“Why are they at the airport?”

“Because it’s the safest place we’re going to have right now. We’ve burnt around the airport.”

At 10:00 p.m., Michel decided to move his officers to the airport too—their cots, their clothes, everything. “I did have a conversation with my command group at that time and I said, ‘This is not going to be a consensus-concept decision. I’m not taking a chance. I’m just telling you we’re going to move forward, unless you have a major objection or a different scenario where you want us to move somewhere else.’ Everybody was like, ‘No, we’re all in. That’s the right thing to do.’” A couple officers from the logistics team went up ahead and assessed the situation. One of them told Michel he had space for sixty officers in the terminal.

Michel asked, “What else is there?”

“We have hangars, but there are planes in them.”

“Well you’re moving planes, so cut the locks, get in, open up so that we have a space. We’ll pay the repairs, everything that needs to be done after the fact, but right now I need to put people there so they can sleep because they need to go back to work tomorrow.”

Michel told his command group that he would be staying the night at City Hall. He also said, “You know, I’m not asking you to stay. I’m okay with you going.” All four said, “No, no, we’re okay.” They remained behind while everyone else moved. Michel explained, “Where we were was the best place for us to monitor, to get information. I had already asked our technical group to move half of our command centre to the airport so that if we were to go there, it was ready for us. But it wasn’t set up. If I was going there right away, I had very limited communications, very limited access to everything that was required for us to make proper decisions.” He added, “We had set ourselves up a route and we knew that the vehicles were there ready to go if it really hit the fan.” He also continued to track what the fire was doing.

However, as Superintendent Dave Attfield reminded me, “In this case, you had dynamic fire behaviour, which was changeable and unpredictable.” In other words, it was challenging to say what would happen. I met Dave at the BC RCMP Headquarters in Surrey. He was the Gold Commander during the fires, responsible for all areas in BC in which major fires had erupted. His regular post is Chief Deputy Criminal Operations Officer for Core Policing. Superintendent John Brewer, who was a Silver Commander during the fires, was also at the meeting.

John saw Michel’s decision this way: “He was acting in the best tradition of the RCMP, saying ‘I may die tonight but I’ll make sure that my members get out.’” John is a member of the Lower Similkameen Indian Band and is normally responsible for a number of portfolios, including First Nations Policing. He said, “Thinking about that still gives me chills. He slept right at City Hall knowing that was ground zero if it ever went.” John, who served in Afghanistan in 2010 as a NATO Senior Police Advisor, added, “Outside of Afghanistan, that evacuation was one of the hardest nights I had ever had. We stayed up all night here too.”

The steady stream of traffic out of Williams Lake continued. As night fell, people on the road could see a string of lights ahead of them and a dark red glow behind. They had no idea whether they would see their homes again. Ten thousand people left the city in seven thousand vehicles. The convoy took nine and a half hours to pass through 100 Mile House. It was a gear-laden exodus. Brian McNaughton said, “We’d recognize a husband with a pickup pulling a fifth wheel and the wife in the next pickup pulling the horse trailer and the oldest child driving the third vehicle.” Svend told me that an RCMP officer from Port Moody, who was off-duty, filmed the whole procession—“every single car.” Later Svend watched the first four or five minutes of the video. “But I stopped. It just got to be too much.”

The evacuation went surprisingly smoothly, especially considering the number of vehicles on the road. “People were extremely polite,” Brian said. “I didn’t even see a hint of road rage. We didn’t pass anybody and nobody passed us all the way from Williams Lake right through to Little Fort.” One woman fell asleep at the wheel and slid off the highway. But she was not seriously injured.

At Little Fort, the RCMP was stopping traffic from going west on Highway 24 so the evacuees coming east could occupy both lanes. Pam Jim told me that, despite this arrangement, the vehicles were bumper-to-bumper, towing trailers on the steep hill leading down from McDonald Summit into the village: “People were hauling loads of quads. There was a snowmobile in a twelve-foot boat on a trailer. Chickens were in a house-type cage on a Suburban.”

Jim’s Food Market was founded by Kam Jim’s grandfather in 1919. A Cariboo institution, it was close to celebrating its one hundredth anniversary. The Jims had deep roots in their small but historic community, which got its start in the 1840s as a stopping point on the Hudson’s Bay Company Brigade Trail. As Pam watched the train of vehicles passing by, she began to think about the people in them. They were under stress and didn’t always know where they were headed. Many had been evacuated just before suppertime and didn’t get any food. They had been on the road for seven hours and were tired and hungry. Pam told me, “Jenny and Wyatt [her daughter and her boyfriend] and I started making some sandwiches for them. Some of them just about cried when they got that sandwich. They’d ask, ‘Do I have to pay?’ and I said, ‘No you don’t. Take a sandwich.’ They didn’t even ask what was on them. We started running out of bread. So we made wraps. Then we ran out of energy and food about 2:30 or 3:00 a.m. We gave away a couple hundred easy.”

Pam closed her kitchen, but she wasn’t able to go to bed just yet. The gas station was almost out of fuel. When she called Husky to deliver more, she was told no drivers were available because they had all worked the maximum amount of overtime permitted. She called the RCMP, who called Husky, who then agreed to send a delivery from Kamloops. It arrived at 4 a.m., just before the pumps ran dry. “I gave the driver coffee, whatever he wanted,” Pam said. “I was so appreciative of him.” And then she finally turned in.

By 3:00 a.m., the winds had calmed down. As Michel recalled, “We were told that the fire had basically changed direction at one of the breaks. If my memory serves me well, I think it was the three-kilometre break. It actually stopped. But it also had crossed Highway 97, which cut our highway access to the north again.” Still, the situation seemed more stable, so Michel decided to pay a visit to the Williams Lake Airport. It was like a refugee camp: “I had people sleeping underneath the wings of planes on the tarmac. I had some people on couches, some people in chairs and some people on the floor. People pretty much everywhere.”

Half an hour later, when he was satisfied that his members were all okay, he returned to the command centre. At least the immediate threat to Williams Lake had gone down a notch. Michel told the officers at the command post that they could catch some sleep—but not a lot of sleep, mind you. Michel was back on his computer at 5:00 a.m., updating his superiors on the latest developments.

At 7:00, Michel did his normal morning briefing with the people coming off shift and those who were coming on. “I updated them on the evacuation and told them what an awesome job they had done. I told them very clearly, ‘You know, my goal over the next twenty-four hours is basically to get you shelter, food, a place to have a shower and a place to do your normal daily functions.’”

However, it wasn’t as easy as it might sound. “We had a moment of reckoning,” Dave Attfield told me. The RCMP had been relying on the Cariboo Bethel Church to provide three meals a day for about three hundred officers. A dozen volunteers had been cooking up a storm, starting with a dinner on July 12. (They had help. The pastor, Jeremy Vogt, told me that the Cariboo Community Church, a sister organization, made bag lunches. Local grocery stores, Safeway, Save-On Foods and Wholesale Club donated food or sold it to the church at wholesale prices. People in the community brought baking. One woman brought six pecan pies.) On July 15, volunteers at the church served breakfast and lunch and were just about to dish up a Mexican-style enchilada casserole when they were evacuated along with everyone else. They scrambled to put things away and left as quickly as they could.

The RCMP had some military-style ready-to-eat meals, but the supplies would only last until July 17. And on that day, they would be marginal: “We had a breakfast and half a lunch for all our members,” John recalled. Dave wrote in his briefing notes to his superiors in Ottawa, “We have lost the ability to feed our members.” He immediately received an emergency procurement contract worth about $1 million. This would allow him to establish a field kitchen that could supply meals and boxed lunches for thirty days. It would also let him purchase more military rations to use until the kitchen was running.

It took several phone calls to locate a supplier who had a stock of military rations on hand, but eventually one was found—in the US. “They were palletizing them and putting them on a plane out of Chicago,” John said. “It was landing at six o’clock in the morning at Vancouver airport. So I had two members there in vehicles as soon as that plane landed. ‘You get out there and start loading,’ I said.” When one of the young corporals that John charged with the duty got to the airport, he discovered a hitch. “He phoned me,” John recalled. “He said, ‘Sir, the delivery has to go through customs. It has to be inspected. We can’t do anything. It’s going to take almost a day,’ I’m like, ‘I don’t care how you get it. At gun point,’ I said. ‘I’m good with that.’ It was a verbal stare-down with customs to get it through because nobody understood just how close we were to running out of food. Even though there’s a grocery in Williams Lake, it had been evacuated. You’d have to have pretty exceptional circumstances for the RCMP to kick in a door and start looting for food. It worked out pretty well for us. We made it through, but we were a meal and a half away from not being able to feed, it was that close.”

The winds died down and the threat to Williams Lake abated. Michel arranged for two local hotels to accommodate his officers. Of course, the hotel staff had been evacuated. “We became innkeepers,” Michel said. A mobile kitchen in Alberta’s oil patch was shipped to Williams Lake. Food was procured as well and on July 20, the officers were finally able to enjoy a hot, freshly cooked meal. Michel left Williams Lake the next day. His first week-long tour on the fires was over. He came back, however, after the evacuation order for Williams Lake was downgraded to an alert on July 27 and the community was welcoming its residents back. “That was a good feeling,” he said.

Brian McNaughton and his wife first heard about the evacuation order for Williams Lake being rescinded on social media, while they were staying at his niece’s place in Kamloops. “My wife said, ‘We’ll just kind of tidy up and we’ll leave tomorrow morning,’” Brian recalled. “I said, ‘We’re out of here.’” They packed up and a few hours later were home again: “Turning the corner and then turning in the driveway and seeing the house still standing was surreal. I had in my mind I was going to come back to brown lawn and everything shrivelled. I had two tomato plants that didn’t get watered for three weeks and survived. My wife had plants all over the deck and one plant died but the lion’s share survived. Still, the nerve ends are raw. If you watch a lot of catastrophes in the world—you know, hurricanes in Florida—you go, ‘Oh those poor people.’ But now I watch the people in Burns Lake and I know exactly what they’re going through and it sends shivers down your spine. You look around and you go, ‘It could happen to me again.’ It’s a very raw emotion. I don’t think there’s anyone that goes through this who doesn’t experience lingering effects.”