Chapter 12 Go Sam, Go

“I need to know who’s willing to fight fire,” Gord said. “You know, it’s not if we get a call, it’s when we get a call.” Samantha Smolen, or Sam, as she is usually called, didn’t hesitate at all. “I’m super keen,” she said. For five years, Sam had worked as a forest technician for Gord Chipman of Alkali Resource Management. She had surveyed forests, planned tree harvesting, supervised planting and managed cone picking. Though she had never fought fires before, she had taken her S-100 training, a basic course in fire suppression and safety. She was eager to apply what she had learned and at age thirty-two was ready for some adventure.

Sam told me about her July 7 meeting with Gord as we spoke in a small café in North Vancouver. A blond woman with a warm smile, she had gone to school at Handsworth, a high school my kids had also attended, and graduated from UBC with a B.Sc. in Natural Resource Conservation. She was taking additional courses there to qualify as a registered professional forester.

In early July, Gord already had the usual number of crews available on standby to fight fires. But because the summer of 2017 had all the signs of being exceptionally hot and dry, he was pretty sure BC Wildfire would want to hire more than the regular workers. Normal logging operations were shut down due to the hazardous conditions, so he called a meeting of his dozen forest technicians in Alkali Lake to see if any of them might be interested in helping out on the fires.

There was only one difficulty for Sam. She had arranged to visit Vancouver for a few days, so she couldn’t begin right away. Gord agreed to let her start after her trip. But once she got down to the coast, she realized fires were erupting all over the province. “I was visiting family,” Sam recalled, “and I was worried about my friends in Alkali. I was starting to freak out because I felt like I needed to get back there to help. So my roommate said, ‘Well if you want to go, I’ll drive you back.’” Generally the trip would take about seven hours, but by July 8, several highways leading to the Cariboo-Chilcotin were closed due to the fires: Highway 97, Highway 97C, Highway 1 and Highway 99. Still, in her years up north, Sam had become acquainted with the ways, the network of dirt roads of varying degrees of drivability that criss-cross the backcountry. She and her friend got through, but it took them twelve hours.

Sam arrived in Williams Lake late on Sunday, July 9, but she went to see her office administrator anyway. She got her Nomex, the de rigueur clothing for firefighters, and was assigned to a crew. Glen Chelsea was the crew boss; Dave Dan, Jason Walch and Brett Harry were the other members of the team. Sam was the only woman in the group and the only non-Indigenous person. Being in a minority position like that didn’t bother her one bit. She praised the fellows she worked with: “They were great guys.” However, she did recall one of the problems of being a woman in a male environment: “It was pretty funny at first being the only girl. I was laughing ’cause we have to roll up the hoses a certain way and I could barely bend in these pants.” (Eventually, she got a pair of Nomex more suited to a female form.) The guys teased her, but she got their respect for her skills with a compass and GPS points, which she had acquired as a forest technician. When Gord wanted her to return to regular duties after her first fourteen-day tour on the fires, Glen told her he had complained: “Gord, no, you’re not taking her. If you take her, I’m leaving.” Gord let her do a second tour with Glen.

On July 10, a co-worker took Sam and the rest of her crew to Riske Creek, a small ranching and logging community in the rolling grasslands fifty kilometres west of Williams Lake, along Highway 20. There they met up with Gord, who had brought five more crews with him. For three days, until the BC Wildfire Service could get one of its incident commanders on-site, he also helped coordinate the activities of the logging companies supplying heavy equipment.

Riske Creek dates back to the 1860s, when L.W. Riske, a Polish immigrant, established a flour mill and sawmill in the area. The community sprawls; houses are a good distance apart from one another. But it is also tight-knit; many of the ninety residents know each other very well. One local rancher joked with me that as he had lived in Riske Creek for a mere thirty years, he was still considered a newcomer.

From July 7 on, when multiple lightning strikes hit the Chilcotin, the locals had been active in their own defense. Working long, gruelling days, they had constructed ten kilometres of firebreaks. “It was amazing how much guard they built just trying to get in front of the fire, trying to cap it off,” Gord said to me. “But the fire kept jumping these guards, no matter how many they put down. It was so dry the fire would burn right across the guards. There was so much wind. The embers were the biggest issue. They just kept on blowing across the guards and then started another fire.”

“At first, things were disorganized,” Sam said. “The government ministry guys, the red shirts, weren’t there yet. We didn’t do a whole lot that first day. Gord went up a few times in the helicopter to check things out. I was a little bit nervous because I had never done it before. But I felt prepared.” Once they got their bearings, Sam and her teammates were able to make headway. Using hoses and hand tools, they were “blacklining”—pushing the fires back about thirty metres from roadways and making wider guards. But on July 15, the winds picked up again. They were working on the road leading to the Riske Creek transfer station when the fire jumped the buffer zone the crew had created, as well as the road itself. Sam had never seen anything like it. She was astonished by how easily the trees caught fire and then crashed around them, scattering sparks as they fell. The crew retreated to Highway 20, and then the members were radioed instructions to go to a house in danger of succumbing.

When she came to the white house with blue trim in a grove of trees, Sam recalled, “You could just see the flames. Your adrenaline is pumping and you want to stop the fire from burning down this house. I showed up and someone said, ‘Are you doing anything?’ And I said, ‘No.’ He said, ‘Grab this hose.’ So I just grabbed it and everyone around was kind of busy or frantic or whatever and I crawled under a fence and started putting out the fire. No one was helping me. It was one-and-a-half-inch hose. We were taking turns rushing in around the house. It was so smoky and the guy was bombing water ’round the house with the helicopter. We had danger tree fallers as well, who were falling some trees and cutting them into smaller pieces to mitigate the spread.”

Blake Chipman was on the water tender that was supplying Sam’s hose. He was Gord Chipman’s father, and had thirty years of experience in the woods, as a logger and firefighter. The BC Wildfire Service had hired him in the springtime. “We’re usually on standby from morning ’til night. When a fire happens, they call us and we go,” he explained in a phone interview. He remembered Sam vividly. “I’m on top of my truck with a pump. And this is basically a big fire. When she went below the road, there was raging flames within fifteen to twenty feet of her. And she actually put that fire out. She just did her job. And if she wouldn’t have got it there, then it would’ve continued on. A good, hard-working woman. Some of the other crews were quite disappointing actually. Fighting fire, you think everybody would try and, you know, do the best job they can. Yeah, but it wasn’t the case sometimes. A lot of times it was just a lot of sitting around and people weren’t really interested in working. It was hard to light a fire under them,” he said and chuckled.

Sam said three contract crews from Alkali Lake and two from the Toosey First Nation in Riske Creek were deployed to save the house. Despite this effort, the fire was quickly becoming unmanageable. The winds were strong and the fire was “basically all around us,” Sam said.

“That fire was actually casting the fire ahead of itself by about a hundred yards,” Blake recalled. “It was throwing balls of fire the size of the hood of your vehicle. The trees were about 120 feet tall and the flames were thirty to forty feet higher than the trees.41 My dog was in the truck and I had to roll up the windows so he wouldn’t burn up because there was a lot of embers and shit flying around. Oh yeah, it was quite drastic there.”

By then, Shelly Harnden had taken over as the incident commander for the Riske Creek fire. She decided the firefighters had better retreat and go back to the Old School in Riske Creek, an adult training centre, which the BC Wildfire Service was using as a base. “When we left that house,” Sam said, “the fire was on both sides of the highway at one point.” She was driving and as soon as she saw the flames ahead of her, she looked at Glen, her supervisor, questioningly. He said, “Just go, Sam, just go.” She stayed in the middle of the road to keep the maximum distance between the vehicle and the fire. She wasn’t too worried, “But you’d want to go fast,” she pointed out. While she was waiting with the other firefighters at the base to receive directions, Sam learned that both Williams Lake and Alkali Lake were being evacuated and that it was now too dangerous for her crew to be in Riske Creek. “But there was no instruction like ‘Come back at this time,’ or, you know, ‘Check in with this person or with me or whoever.’ There was nothing. It was just like, ‘I don’t know. Just go.’

“We sat in the traffic trying to get into town while everyone was trying to get out. I don’t know if ‘scared’ is necessarily the right word, but I was very anxious,” Sam said. The steady stream of cars heading out of Williams Lake and the departure of thousands of people were strong signals that the town was not safe. “But I didn’t know whether I was supposed to be leaving town with everyone or staying. I was just kind of following my gut and staying in town.”

When Sam got back to her place, it was 9:00 or 9:30 p.m. Her roommates were gone and the families of her crew members had been evacuated. Sam said, “I asked my crew, ‘Well, why don’t you guys just stay with me? I’ve got beds and bedrooms.’ So they stayed. Actually one of the guys put his gear in the wash.”

“I texted Gord, my boss, saying, ‘Hey Gord, I’ve got my crew with me at my place. Can you tell me what’s going on?’ I’m kind of stressed. I don’t know what to do—if I should be leaving or if I can stay. Nobody told me that.” Sam had got used to operating within a chain of command, being guided by clear instructions. But she didn’t have any and she found the situation disturbing. “I texted Gord, saying, ‘We’re ready to go,’ thinking he would give us some direction in the morning. But he texts me back, or calls me back, and says, ‘Are you sure you’re ready to go?’ And I’m like, ‘Yes, we’re ready to go.’ Then he asks, ‘Can you be up at Slater Mountain in half an hour or an hour?’

“I told my crew boss and he’s like, ‘We’ll be there.’ He made my buddy take his gear out of the wash and put it on wet. When we drove up it was 11:00 at night.” Slater Mountain is at the north end of Williams Lake, north of the sawmills. When sparks jumped the Fraser River, the mills were at high risk of catching fire and igniting Williams Lake. The Alkali crew’s assignment was simple to describe: “Put out any fires caused by the sparks and prevent the flames from spreading to the mills.” But it wasn’t so easy to execute.

“We got up there,” Sam recalled. “It was pitch black and we couldn’t see anything except the red glow of the fire. The wind was howling. We could hear a machine bulldozing trees over to make a guard. Not even cutting them and throwing them aside or anything, just plowing them over. They had two guys on the radio. The line locator was out there on foot with a GPS, hanging boundary for the guy in the machine right behind him. We couldn’t see a single thing except for the trees moving and falling down, the headlights of the machine and the glow of the fire. We could hear the wind roaring and they wanted us go out there and put out any sparks. I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, I don’t want to get out of the vehicle. This is not safe.’”

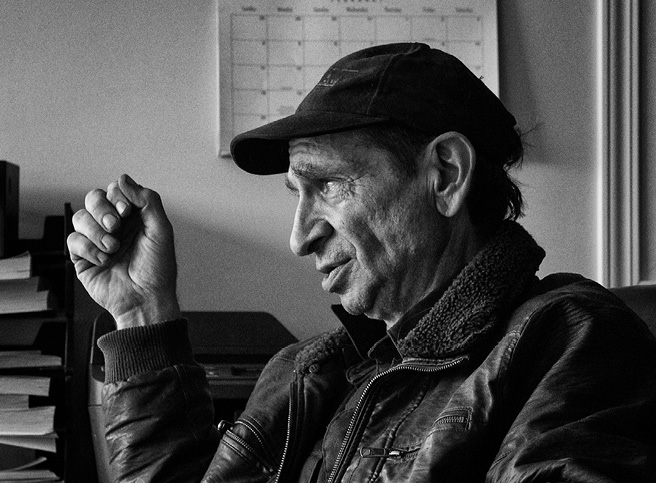

Lee Todd, the president of Eldorado Log Hauling, is a friend of Gord Chipman’s and together they had organized the operation. I talked to Lee at his company office on the lower slopes of Slater Mountain and learned that he’d had a hardscrabble start in life. After leaving his home in Riske Creek at fourteen, he’d hitchhiked to Vancouver, where he’d spent one winter living in a cardboard box. Eventually, he moved to Williams Lake, built a thriving business and appreciated the chances he’d had. “I love this town,” he said. “It’s vibrant, a very good town.” He told me that in 2017, after working all summer on the fires, he was diagnosed with cancer and went through a gruelling eight months of chemo. Despite that, his zeal for the subject of fires was undiminished.

On July 15, Lee’s wife phoned him to say that an A-Star helicopter had landed on their property, just a few kilometres away from his business, higher on the mountain. “So I go roaring up in my truck,” Lee remembered. A BC Wildfire official emerged from the chopper and said, “Lee, run like hell, you’ve got twenty minutes and then you’re toast.”

“I’m thinking he’s one of the higher echelons, he should know his stuff, so I get the wife down here and my motorhome and got my valuable belongings out of our house.” But Lee could not resist having a look at the fire himself. He has been fighting fires ever since he was a teenager, so forty-six or forty-seven years. He jumped in the helicopter that he used for his business. “I went up and, excuse my language, but for fuck’s sake! You know, when they’d seen it, it was probably a cat 5 or 6. I could see it from here—a mushroom atomic bomb. It was uncontrollable, with the wind in the afternoon. Only a fool would have been endangering people’s lives by putting them on the smoke in front of that fire. I’m not that stupid. But as soon as I saw it, I thought, ‘Man it’s 4:00 or 5:00 in the afternoon. It’s going to start to cool off. It’s going to crest the mountain and then it’s slightly downhill to my place. There’s a two-hundred-metre fireguard power line right behind my place. I can stop that fire. That’s not a problem.”

Lee phoned the Cariboo Fire Centre and said, “Come and help me. We can stop that fire. There’s no need to let the whole north end of town burn up. They said I was a fool and an idiot to go up there. I said, ‘Well no, I’m not. I’m telling you that that fire is quite stoppable and it’s just about peaked at cat 6 and it’ll be like a cat 2 or 3 in a few hours. Come and help me.’ They said, ‘No, you are on your own.’ I said, ‘Okay, I’m on my own and fuck you.’ Excuse me, I get crude sometimes, maybe a little too passionate.

“I wasn’t putting people in danger,” Lee insisted. He phoned a few friends who said they would be there as soon as possible. Pretty soon he had four Cats and then Gord Chipman brought two crews from Alkali. This is why Sam found herself on spark watch on the top of Slater Mountain in the early hours of the morning on July 16.

Sam was not easily put off her game, but she admitted: “I was a little bit scared.” She and the rest of the firefighters from Alkali Lake waited until the machines were done knocking trees over, and then they looked for flare-ups and systematically put them out. “These fires were quite small, about the size of a campfire,” said Sam. The crew members were able to refill their backpacks and keep going with the help of Lee Todd’s old 6 × 6 army truck, a heavy off-road vehicle with three axles and six wheels, carrying a six-thousand-gallon water tank.

While the Alkali crews were putting out sparks, Lee and the other Cat operators built a five-kilometre guard tying into the Soda Creek Road near Blocks R Us, a landscape supply company. They worked fourteen hours straight. Lee is convinced that if they had arrived even one hour later than they did, they wouldn’t have been able to stop the fire. “This whole end of town would have been burnt,” he told me. “There’s a huge disconnection between the Fire Centre and us as a people. Together no fire could beat us. But there’s this thing about them-against-us and us-against-them which is totally unconstructive.”

George Abbott and Maureen Chapman wrote a detailed government report about the fires of 2017 that contains recommendations about a host of different issues. In it, they acknowledged the contribution of people like Lee, who worked to limit the spread of wildfires threatening their communities. They proposed that BC develop partnerships with key community members “to provide increased response capacity.”42

As the sky lightened, Sam could see something of the lay of the land. Through the smoke she was able to discern a farm with horses, cattle, a donkey—and peacocks. Sam met George Keener, the owner, who had lived there for many years in a small ninety-year-old cabin. He was very grateful for the help he had received, and he told Sam, “You’re always welcome here. Come up any time and I’ll make you a cup of coffee and something to eat.” That the cabin survived was something of a miracle. When Lee had arrived first with his friends, its roof was already on fire and he wasn’t at all sure they could save it.

Bridgitte Pinchbeck, the office administrator at Eldorado Logging, laid on a big pancake breakfast for the firefighters at the company office, where a small base had been set up. “Gord came down,” Sam told me. “He had a big smile and he’s like, ‘You guys saved Williams Lake.’ I don’t know if it’s true or not, but the moment when he said that felt really good. Gord doesn’t dish out a whole lot of compliments.” Sam and the rest of the crew had not slept for twenty-four hours and they were exhausted. But still they were able to muster one more burst of energy. “We were all like, ‘High fives,’” Sam said.

Gord told the crew to take some time off and come back at 8:00 in the evening for another session of night ops. When they came back, the donkey treated Sam like an old friend and began following her around. This time, the fires they were putting out were a little larger than the night before, but definitely containable. Sam spent another couple of hours on spark duty, but then Gord called her and said, “Okay, change of plans. You’re going back out to Riske Creek. So go home. Go to sleep. Sleep as much as you possibly can and just get out there.”

“We went back and slept as long as we could. Then we showed up at Riske Creek and everyone out there started yelling at us. ‘Where were you? What have you been doing?’ And the other crew bosses and guys that I work with started saying, ‘You were supposed to be here at this time,’ and I told them, ‘Nobody told us that. Actually our boss told us to come here when we had enough sleep. I’m sorry, but we were working all night, you know.’ We were like, ‘Well, we saved Williams Lake. We were busy.’”

Back in town, Lee was still having arguments with the BC Wildfire Service. Three days after the fire arrived on Slater Mountain, Lee said, an incident commander showed up and told him he was taking over the fire.

“I said, ‘Fine. Are you going to have a night shift watching sparks?’ The guy blew up. He said, ‘I’m a fire behaviour specialist and in my opinion that fire is not likely to cross that guard you built.’”

Then it was Lee’s turn to explode: “For the sake of two kids it would cost us eight hundred dollars to run up and down there all night, you’d risk a whole fucking town and five hundred houses?’ So I put two of my kids there, actually four of them, two girls and two guys and two quads with water, water on the back, running up and down there all night, just keeping an eye out because the only danger was a spark crossing. They watched every night.”

When I talked to Williams Lake mayor Walt Cobb about the log piles north of the city, which never did catch on fire, he said, “We’re so fortunate. Two kilometres from the city boundaries, the wind changed or whatever. God was looking after us, I guess. The fire basically just stopped.” He wasn’t aware that human intervention may also have played a role.

Blake Chipman said that Gord and Lee “didn’t wait for any slaps on the back about it and they still to this day don’t care about that. They just did what they had to do at that time. Basically what they cared about is saving what they could.” It was important to realize that “they were all experienced people,” Blake said. “They were not just a bunch of hillbillies grabbing ahold of a garden hose. They knew what they were doing. They got around very close to the edge of the fire and then ran a water truck. They stopped all the hot spots from jumping their fireguard and by morning it was under control.”

Sam didn’t get to bask in glory during her final stint at Riske Creek either. “It was a lot of infrastructure protection. We were putting out the little smouldering ground fires. And then doing patrol along the highway, sniffing out the smoke and, you know, turning the soil, and making sure it’s really out.” The house that Sam left on July 15 had survived. “When we went back, we were really surprised that the house was there. It burned all around. It is just so weird the way fire works. You know, one house may burn down and then the neighbour’s won’t.”

Sam and I had been talking for over an hour in the café. We were about to leave but Sam had one more thought she wanted to share. She had actually enjoyed the firefights, she said. “It was exciting and I felt like I was making a difference and helping. Once you get to the end, and you’re just on patrol and doing mop-up, then it’s like, ‘Okay, I’ll go back and do my other work.’” (After her second tour on the fires, Sam returned to her regular job.) As an inexperienced firefighter, Sam recalled, “I was always at the bottom of the barrel, but happily it was a good experience.”