Chapter Four

In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to Andrew Jackson, a young political leader in Tennessee. He told Jackson that the government should encourage Native American people to sell their forests and become farmers, like the whites.

Three decades later, Andrew Jackson was president. Under his leadership, the government forced thousands of Indians off their land. Farming offered no protection—even Native people who were farmers were removed from land that white Americans desired. Jackson’s relationship with the Native Americans, however, had begun long before he became president. His own fortunes were tied to what happened to the Indians.

Jackson Against the Indians

Andrew Jackson moved from North Carolina to Nashville, Tennessee, in 1787. In Tennessee he practiced law, opened stores, and became a land speculator—someone who buys a lot of land and hopes to sell it for a profit. For example, Jackson paid $100 for 2,500 acres of land along the Mississippi River and immediately sold half of it for $312. Years later he sold the rest of the land for $5,000. The land had once belonged to the Chickasaw people, but Jackson had negotiated a treaty with these Native Americans and opened it to white settlement.

Jackson also had a triumphant military career in wars against the Indians. With the rank of general he led American troops into battle with the Creek people, whom he called “savage bloodhounds” and “blood thirsty barbarians.” When Jackson learned that hostile Creek had killed more than two hundred whites at Fort Mims, near what is now Mobile, Alabama, he vowed revenge.

On March 27, 1814, Jackson took his revenge in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. At a bend in Alabama’s Tallapoosa River, Jackson and his troops surrounded eight hundred Creek and killed most of them, including women and children. Afterward his soldiers made bridle reins out of strips of skin taken from the corpses, and Jackson sent clothing worn by the dead warriors to the ladies of Tennessee. He told his troops:

These fiends . . . will no longer murder our women and children, or disturb the quiet of our borders . . . They have disappeared from the face of the Earth. In their places a new generation will arise who will know their duties better.

Honored as a hero of the Indian wars, Jackson was elected president in 1828. He supported the state governments of Mississippi and Georgia, which wanted to abolish Indian tribal units and let whites settle on lands that the tribes had been farming. The tribes’ ownership of those lands had been guaranteed by treaties with the federal, or national, government—but the states were breaking the treaties.

As Jackson watched the treaties being broken, he claimed he was helpless to do anything about it. This was not true. Authority over the Indians lay with the federal government, not the states, and in 1832 the US Supreme Court ruled that states had no power to make laws that affected Indian territories. Jackson simply refused to uphold the court’s decision. Behind the scenes, in fact, he was working to have the Indians removed from their land.

The states’ goal in breaking the treaties was to end the authority of the tribal chiefs, turning them into ordinary citizens who must follow the laws of the whites rather than their own laws. The chiefs could then be bullied, bribed, or persuaded to move off their lands, and the rest of the Indians would follow. All Jackson had to do was stay out of the way.

In Jackson’s view, Indians could not survive within white society. His solution was to set aside a territory west of the Mississippi River “to be guaranteed to the Indian tribes as long as they shall occupy it . . . as long as the grass grows, or water runs.” Jackson advised the Indians to move west. Beyond the borders of white society, they would be free to live in peace under their own governments.

Jackson spoke of himself as a good father, wanting only the best for his “red children.” Taking the attitude that his position was both legal and morally right, he uprooted seventy thousand Native Americans from their homes and ordered soldiers to move them west of the Mississippi. The removal of the Indians, like the importing of African slaves to work as plantation laborers, helped turn the American South into a cotton kingdom. The major cotton-growing states—Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana—were carved out of Indian Territory.

The Choctaw Become “Wanderers in a Strange Land”

The Choctaw of Mississippi were a farming people long before the arrival of whites. They grew corn, beans, squash, pumpkins, and watermelons, and they shared their food freely with tribe members and with neighboring communities that suffered from crop failures.

By the early nineteenth century, many Choctaw had turned to raising cows and pigs in enclosed farms, in the manner of white farmers. Some Choctaw grew cotton to sell, and some owned black slaves. The government did not treat the farming Choctaw in the same way it treated white planters, however. Farming Choctaw suffered the same fate as the rest of their people.

In 1830 the Mississippi state government ended the legal identity of the Choctaw Nation and its ability to govern itself. This meant that individual Choctaw now had to obey state authority. Nine months later, officials from the federal government met with the Choctaw at Dancing Rabbit Creek to negotiate a treaty that would turn their lands over to the government and remove them to the west.

The Choctaw turned down the offer, saying, “It is the voice of a very large majority of the people here present not to sell the land of their forefathers.” Thinking that the meeting was over, many Choctaw left. But the federal officials refused to accept no for an answer. They bluntly told the remaining chiefs that the Choctaw must be removed from Mississippi, or they would feel the weight of state law. If they resisted, they would be destroyed by federal forces. Under this threat, the chiefs finally signed the treaty.

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek gave more than ten million acres of Choctaw land to the federal government. Not all Choctaw had to migrate to the lands west of the Mississippi River, however. Individuals and families could register with federal agents for a land grant in Mississippi, like any white settler. This made it look as if the program gave Choctaw a fair chance to succeed in white society as individual landowners.

In reality, the Choctaw never had a chance. As soon as an Indian acquired a land grant, a speculator loaned money to the Indian, with the title to the land as insurance for the loan. When the Indian was unable to make enough money to repay the loan, the speculator claimed ownership of the land. In other cases, white settlers simply moved onto Indian land and squatted there, refusing to move. The Indians who had claimed land grants and then lost them had to move west, along with the rest of the Choctaw.

A year after the treaty, thousands of Choctaw began their trek to the Indian Territory across the Mississippi River. On the way, many of them encountered terrible winter storms. French traveler Alexis de Toqueville witnessed the Choctaw crossing the great river and wrote of the conditions they faced:

It was then the middle of winter, and the cold was unusually severe; the snow had frozen hard upon the ground, and the river was drifting huge masses of ice. The Indians had their families with them, and they brought in their train [procession] the wounded and the sick, with children newly born and old men upon the verge of death.

Uprooted, many Choctaw felt bitter and angry. In his “Farewell Letter to the American People, 1832,” Choctaw Chief George W. Harkins explained why his people left their ancestral lands: “We were hedged in by two evils, and we chose that which we thought least.” The Choctaw had chosen to “suffer and be free” rather than remain under laws that would not let their voices be heard. But they left unwillingly, because their attachment to their native land was strong. “That cord is now broken,” Harkins declared, “and we must go forth as wanderers in a strange land!”

The Cherokee on the Trail of Tears

Like the Choctaw in Mississippi, the Cherokee in Georgia were removed from their lands “legally.” The Cherokee faced the same choice: leave or bow to white rule.

Under the leadership of Principal Chief John Ross, the Cherokee refused to abandon their homes and lands. They insisted that the federal government must honor the treaties it had made—treaties that had granted the Cherokee Nation ownership of its territory and the right to govern itself. Their appeals fell on deaf ears in Washington. President Jackson sent an official to negotiate a treaty for Cherokee removal.

Not all Cherokee agreed with Chief Ross that they should resist removal. A minority of them supported the idea of removal, and John Ridge, a leader among this group, signed a treaty saying that the Cherokee would leave their land in exchange for a payment of more than three million dollars.

For the treaty to take effect, it had to be ratified, or agreed to, by the entire tribe. The federal official scheduled a meeting for that purpose, but the Georgia militia prevented the Cherokee newspaper from publishing an announcement of the meeting. The militia also threw Chief Ross in jail. Only a tiny fraction of the Cherokee Nation attended the ratification meeting, and no tribal officers were present. Even some federal officials recognized that the treaty was a fraud. Still, President Jackson and the US Congress said it was legal.

The treaty set loose thousands of white settlers who seized the Cherokee lands and forced many Indians to abandon their homes. When the Cherokee refused to migrate, the federal government ordered the military to remove them by force. General Winfield Scott, with seven thousand troops, rounded up the Cherokee in a violent, cruel process, treating them as prisoners.

The Cherokee were marched west in the dead of the winter of 1838–1839. Like the migration of the Choctaw, the journey of the Cherokee brought dreadful suffering. One of the dispossessed Indians said, “Looks like maybe all be dead before we get to new Indian country, but always we keep marching on.” By the time the Cherokee reached the new Indian Territory west of the Mississippi, more than four thousand people—nearly a fourth of this exiled nation—had died on what the tribe still remembers as the Trail of Tears.

“What Shall We Do with the Indians?”

The Plains Indians, who lived west of the Mississippi River, also saw their way of life changed forever by the march of white settlement and civilization. The fate of one Plains tribe, the Pawnee, was similar to that of the Southern Indians.

Traditionally the Pawnee had lived by farming corn and hunting buffalo in central Nebraska and northern Kansas. The buffalo hunt was a sacred activity, and the number of animals killed was strictly limited to what the Pawnee were able to consume. Then, during the nineteenth century, the Pawnee began to take part in the fur trade. Hunting started to become a commercial activity. Contact with white traders also introduced new diseases like smallpox, which reduced the Pawnee population from ten thousand in 1830 to only four thousand in 1845.

By then, an even greater threat to the Pawnee had emerged. It was the railroad. In his 1831 message to Congress, President Jackson praised science for expanding man’s power over nature by linking the cities together with railroads. At that time the United States had just seventy-three miles of railroad track, but the network of railways would grow. Thirty years later in 1860 the United States would have 30,636 miles of track—more than the whole continent of Europe.

The railroad brought a new, modern era, one in which horses and Indians would have no place. “In a few years, like Indians, [horses] will be merely traditional,” declared a newspaper editorial in 1853. The railroads crisscrossed the Plains and reached toward the Pacific Coast, bringing the frontier to an end.

Another writer asked in 1867, “What shall we do with the Indians?” His answer was that the Indians must take their place in white society, under white laws, or be “exterminated.”

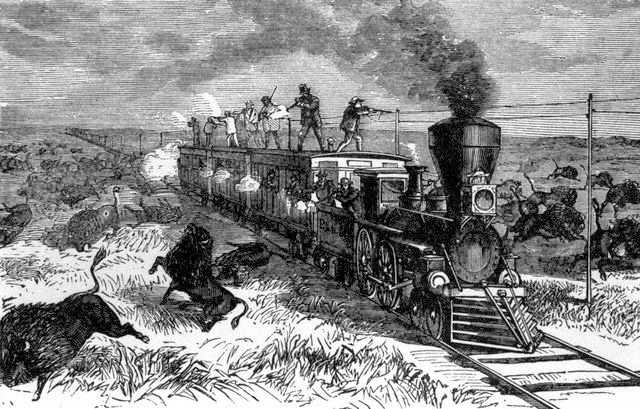

Whites hunting buffalo from a moving train, around 1870.

Railroad Politics

Behind the railroads were powerful corporations, deliberately planning the settlement of the West and the growth of their business interests. Railroad companies saw the Native Americans as obstacles. They lobbied the government for rights-of-way that would let them build tracks through what had been set aside as Indian land.

The railroad companies also pushed for passage of a law called the Indian Appropriation Act of March 3, 1871, which said “no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power, with whom the United States may contract by treaty.” As one lawyer for a railroad company pointed out, the Act destroyed the political existence of the tribes. It allowed the companies to build tracks across America, opening the West to new settlement. All this was seen by whites as the progress of civilization.

Indians saw it very differently. They watched the railroad carry white hunters to the Plains, turning the prairies into buffalo killing fields. They found carcasses rotting along the tracks, a trail of death for the animal that had been the main source of life for the Plains Indians. At the same time, white settlers complained that the Pawnee occupied some of the best land in the region. Settlers, their newspapers, and their leaders called on Washington to remove the Indians.

The Pawnee also found themselves under attack from the Sioux, a Plains people who had lived to the north. Pushed south by the white settlers moving into their lands and by the decline of the buffalo, the Sioux attacked the Pawnee, burned their crops, and stole their food. In 1873 the Sioux attacked a Pawnee hunting party at what came to be known as Massacre Canyon and killed more than a hundred of them.

Stunned by this tragedy, the Pawnee had to decide whether they should retreat to federal reservations for protection. In spite of the anguish of leaving their homeland, most felt they had no choice. They migrated to a reservation in Kansas.

The identity and existence of the Pawnee had depended on the boundlessness of their sky and earth. But now railroad tracks cut across their land like long gashes, and fences enclosed their grasslands where buffalo once roamed. Indians had become a minority on land they had occupied for thousands of years.

A Pawnee named Overtakes the Enemy said, “To do what they [whites] called civilizing us . . . was to destroy us. You know they thought that changing us, getting rid of our old ways and language and names would make us like white men. But why should we want to be like them, cheaters and greedy?” The world the Plains Indians had known was coming to an end.