Chapter Five

Native Americans lived outside of white society’s borders. African Americans, though, lived among whites. In the South they lived on plantations. In the North they lived in ghettos. One black man who knew both these worlds was David Walker.

Born in North Carolina in 1785, Walker was the son of a slave father and a free mother. He inherited his mother’s status and was free. Still, the sight of people who shared his skin color being defined as property filled him with rage against the cruelty and injustice of slavery. Somehow Walker learned to read and write. He studied history and thought about the question of why blacks in America were in such a terrible condition.

Walker continued to reflect on this question after he moved north to Boston, where he sold old clothes. Freedom in Northern society, he realized, was only a pretense. In reality, Northern blacks were treated as inferior, allowed to do only menial jobs such as cleaning white men’s shoes.

Slavery, Walker believed, could be destroyed only through violence. In 1829 he published Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World, in which he said, “Masters want us for their slaves and think nothing of murdering us. . . .” He added that if enslaved blacks ever rose up against their oppressors, it would be “kill or be killed.” Lawmakers in the South prevented Walker’s book from being widely distributed. In the North, even white abolitionists who opposed slavery criticized its strong language. But what Walker had presented was a disturbing view of the condition of blacks in America. They were slaves in the South and outcasts in the North.

Northern Freedom?

In 1860 there were 225,000 African Americans in the Northern states. They were “free,” because the North had abolished slavery after the American Revolution. Still, they were the targets of poisonous racism.

Everywhere blacks experienced discrimination and segregation. They were barred from most hotels and restaurants. In theaters and churches they had to sit in separate sections, always in the back. Black children usually attended separate, inferior schools. Told that their presence in white neighborhoods would lower property values, blacks found themselves trapped in crowded, dirty slums. They were excluded from good jobs—in the 1850s nearly 90 percent of working blacks in New York had menial jobs. “No one will employ me; white boys won’t work with me . . .” a young African American man complained.

Blacks were also limited in their right to vote. In New York, for example, a white man could qualify to vote in a number of ways: by owning property, paying taxes, serving in the militia, or working on the highways. A black man was required to own property in order to vote. Pennsylvania went further. In 1838 it limited the vote to white males only.

In addition, African Americans suffered from attacks by whites. Time and again in Northern cities, white mobs invaded black communities, killing people, and destroying their homes and churches. Philadelphia, the “city of brotherly love,” was the scene of several bloody riots against blacks. In 1834, for example, whites on the rampage forced blacks to flee the city.

Society’s widespread view was that blacks were inferior to whites. Blacks were called childlike, lazy and stupid, or prone to criminal behavior. Interracial relationships were feared as a threat to white racial purity. Indiana and Illinois outlawed interracial marriage, and even where it was legal, it was strongly disapproved of. All in all, for blacks the North was not the Promised Land. They were not slaves, but they were hardly free.

On Southern Plantations

Meanwhile, in the South in 1860, four million African Americans were slaves. They accounted for 35 percent of the total population of the region. The majority of them worked on plantations, large farms with more than twenty slaves.

A slave described the routine of a workday:

The hands are required to be in the cotton field as soon as it is light in the morning, and, with the exception of ten or fifteen minutes, which is given to them at noon to swallow their allowance of cold bacon, they are not permitted to be a moment idle until it is too dark to see, and when the moon is full, they oftentimes labor until the midnight.

To manage their enslaved labor force, masters used various methods of discipline and control. They sometimes used kindness, but they also believed that strict discipline was essential and that they had to make their slaves fear them. Senator James Hammond of South Carolina, who owned more than three hundred slaves, explained, “We have to rely more and more on the power of fear. We are determined to continue Masters, and to do so we have to draw the rein tighter and tighter day by day.” Physical punishment was common.

Masters also used psychological control, trying to brainwash slaves into believing that they were racially inferior and suited for bondage. Kept illiterate and ignorant, they were told that they could not take care of themselves.

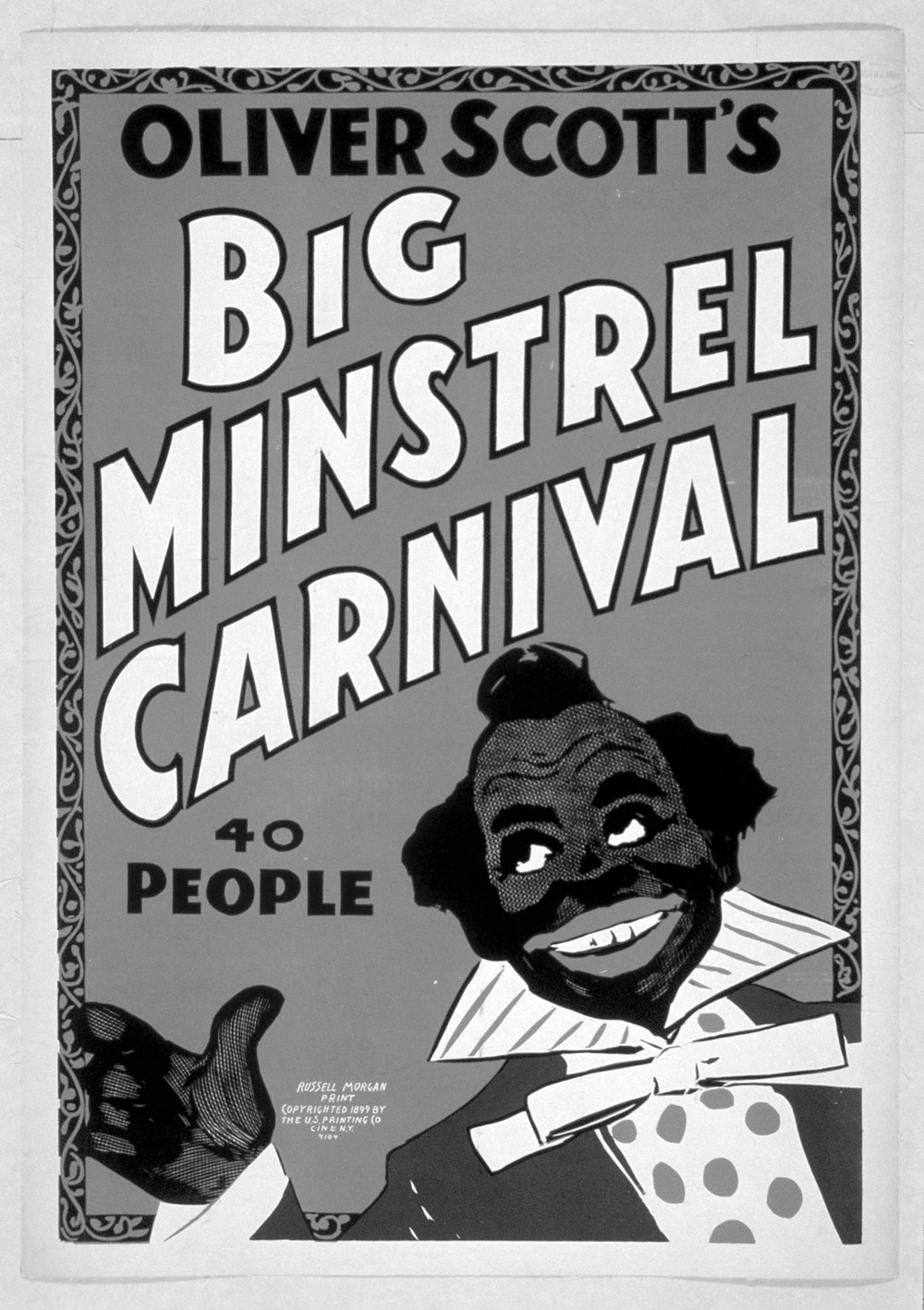

White Southerners held two contrasting images of the African Americans as slaves. In one view, the slaves were childlike, irresponsible, affectionate, lazy, and happy. Together these qualities made up a personality that came to be called the “Sambo”—the smiling slave who loved his or her master.

The image of the smiling slave had special meaning for slaveholders. The world disapproved of American slavery, which made slaveholders want to prove that it was really a good thing. If owners could show their enslaved workers as happy and satisfied, and that slaves needed the protection of their masters, then perhaps they could defend themselves against those who called slavery immoral.

But there was another, darker view of slaves throughout the South. In this view, blacks were savages, barbarians who could turn violently against their masters at any moment. Slaveholders were terrified of black revolts and uprisings. One slaveholder in Louisiana recalled times when every master went to bed with a gun at his side.

Slave uprisings did occur. In 1832 in Virginia, an enslaved man named Nat Turner led seventy other slaves in a violent rebellion that lasted two days and left almost sixty whites dead. Turner admitted that he had no reason to complain of the treatment he had received from his master. The revolt, he said, was sparked by a religious vision. He had seen black and white spirits fighting, and a voice told him to rise up against his enemies with their own weapons.

Before the revolt, Turner had seemed humble, obedient, and well behaved. He may have fit the image of “Sambo,” the happy slave. For slave owners, viewing their slaves as Sambos comforted their troubled consciences, and also reassured them that their slaves were under control. But slaves who behaved like Sambos might have been acting, playing the role of loyal slaves in order to get favors or to survive, while keeping their inner selves hidden. Nat Turner’s rebellion made whites nervous because it showed that even a seemingly “good” slave could be planning their destruction.

The “Sambo” figure in this 1899 poster represents

a white fantasy of African Americans.

African Americans in Southern Cities

Not all slaves lived and worked on plantations. In 1860 there were 70,000 urban slaves in the South, laboring in cloth mills, iron furnaces, and tobacco factories. Many had been “hired out” by their masters to work as wage earners. The masters received weekly payments from the slaves’ employers or from the slaves themselves. One slave in Savannah, Georgia, used the hiring-out system to his own advantage. First he bought his own time from his master at $250 a year, paying in monthly installments. Then he hired seven or eight slaves to work for him.

Hiring-out weakened the slave system. No longer under the direct supervision of their masters, slaves could feel the loosening of the reins. They were taking care of themselves and enjoying a taste of independence. By associating with free laborers, both black and white, they learned what it meant to be free. It would take a devastating war, however, to finally cut the reins that bound the enslaved blacks of the South.

Frederick Douglass: From Slave to Reformer

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery on the Maryland plantation of Thomas Auld around 1818. His mother was a black slave. His father was a white man, possibly Auld. Douglass spent his earliest years in the cabin of his black grandparents, where he was protected from what he later called “the bloody scenes that often occurred on the plantation.”

As a young boy, Douglass was placed in the home of Hugh Auld, his master’s brother, who lived in Baltimore. At first things went well. Auld’s wife, Sophia, seemed like a mother to the young slave. When Douglass developed a strong desire to learn to read, she gave him lessons. The boy learned quickly, and Sophia was proud of his progress—until she told her husband about it.

Hugh Auld angrily banned any more reading lessons, telling Sophia that education would spoil a slave. Her husband’s fury had a damaging effect on Sophia, who not only stopped teaching Douglass but also snatched his book away if she happened to catch him reading. Still, he read whenever he could, and he managed to acquire a few books. He even got spelling lessons from white playmates.

The urban slavery of Baltimore was not as strict and punitive as plantation slavery. It was in Baltimore that Douglass saw that not all blacks were slaves. The sight of free blacks filled him with the desire for escape and freedom. When Douglass was sixteen, however, Thomas Auld sent him to work for a poor farmer named Covey, who was known as a slave breaker. Covey’s instructions were to break Douglass’s spirit and turn him into an obedient slave. Kicked, beaten, and whipped, Douglass refused to break. On the day when he fought back and stood up to the brutal overseer, Douglass felt that he was a freeman in spirit, even though he remained a slave.

Douglass made several attempts to escape to the free states. Finally, in 1838, with the help of friends, he succeeded in making his way by ferry, train, and steamboat to Philadelphia, and from there to the house of an abolitionist, or antislavery activist, in New York. Douglass joined the abolitionist cause. Until his death in 1895 he was a spokesman against slavery and racism. Blacks, Douglass believed, were Americans. He predicted that they would eventually be blended and absorbed into the American people.

The Civil War Brings Freedom

The Civil War was started by the planter class of the South. Although this elite group made up only 5 percent of the Southern white population, it dominated the politics of the region. Defending their right to profit from slavery, the planter class took their states out of the Union in 1861. President Abraham Lincoln, however, refused to let them break up the United States. The result was the long and bitter Civil War between the Union, or Northern states, and the Confederacy, the Southern states that had broken away.

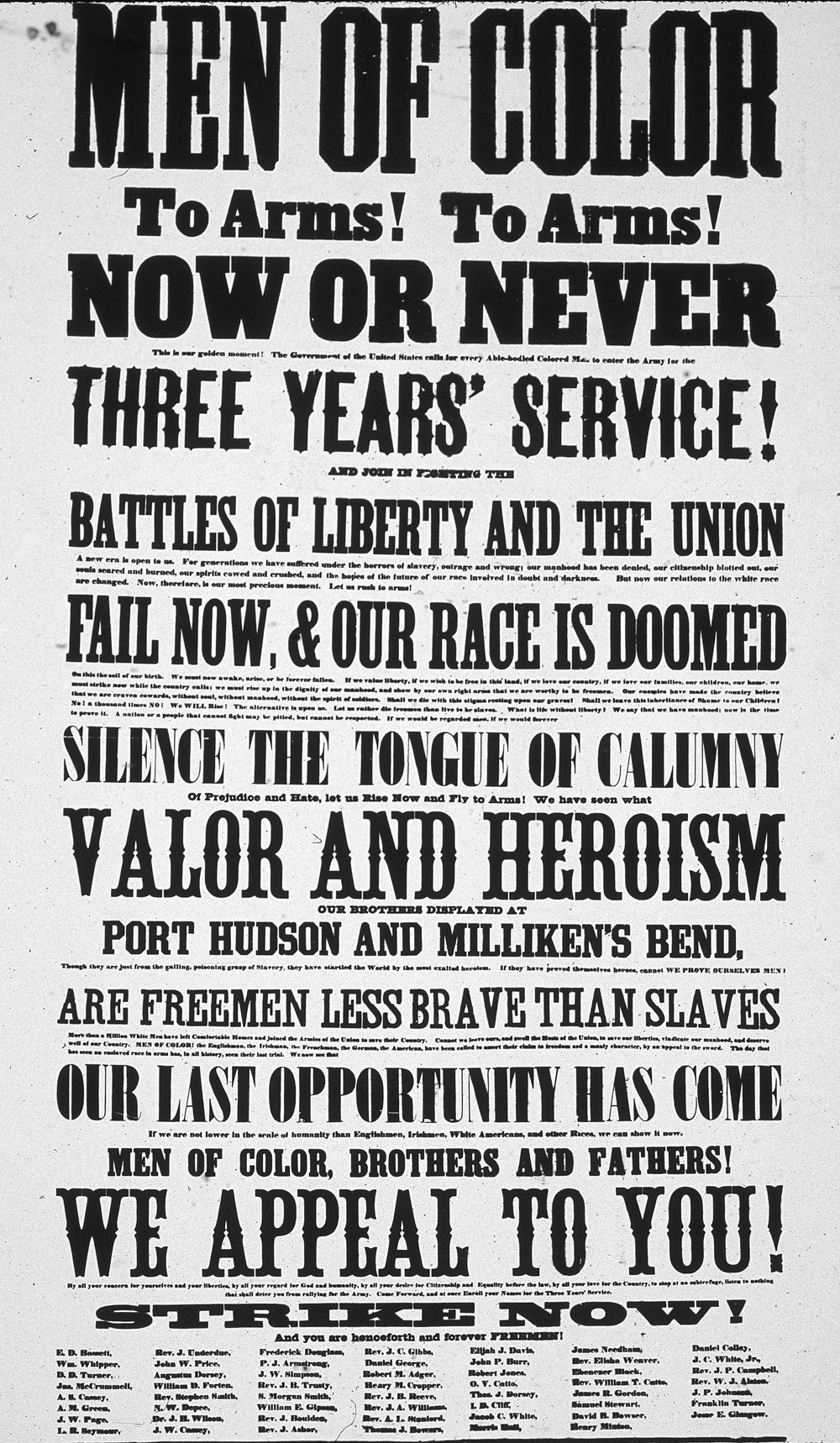

Union army recruitment poster, around 1860.

At first Lincoln refused to let the Northern army enlist African Americans as soldiers, partly because he feared that whites would refuse to fight in an army that had black soldiers. Then, in the spring of 1863, the Union faced a manpower shortage and was at risk of losing the war. Lincoln gave his generals permission to enlist black men.

A total of 186,000 blacks served in the Union army. By war’s end, a third of them would be dead or missing in action. But without the help of African American soldiers, as Lincoln said, the war would have been lost.

The war not only preserved the United States unbroken, it also abolished slavery. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 freed the slaves, and the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified to the US Constitution in 1865, ended the institution of slavery.

Although some slaves mourned the deaths of their masters, or worried about how they would live once they were freed, most excitedly embraced their freedom. Thousands of slaves had deserted their masters during the fighting, running off to the Union camps as soon as they heard that Union troops were in the area. White slave-owners were shocked that their faithful “Sambos” would leave them. One woman complained, “They left without even a good-bye.”

African Americans in the “New South”

After the Civil War, African Americans were free—but now they had to make their way in a society that had been drastically overturned. The freedmen, as former slaves were called, wanted schools and the right to vote, but most of all they wanted land, so that they could support themselves and their families.

A few leading Northern politicians understood the need to give land to the freed slaves. They wanted to break up the estates of Confederate planters and distribute them to the freedmen. Most politicians opposed this idea, however, and it never became law.

During the war, forty thousand blacks had been granted land by a military order from William T. Sherman, a Union general. He set aside large sections of Georgia and South Carolina for black people, who were given titles to forty acres each. Although the titles would not be final until Congress approved the order, the blacks thought they owned the land. But Andrew Johnson, who became president after Lincoln was assassinated, pardoned the Southern planters, who then began to reclaim their former lands and force their former slaves to work for them. When some blacks said they were prepared to defend their acres with guns, federal troops seized the land, tore up the blacks’ title papers, and restored the land to the planters.

This ended the possibility of real freedom. As one Union general told Congress, “I believe it is the policy of the majority of farm owners to prevent Negroes from becoming landholders. They desire to keep the Negroes landless, and as nearly in a condition of slavery as it is possible for them to do.”

Blacks in the South, no longer slaves but unable to get land of their own, became wage earners or sharecroppers, agricultural laborers who worked the land of their former masters in exchange for a part of the crop. Forced to buy goods from stores owned by the planters, they found themselves in a vicious economic cycle, making barely enough to pay their debts, never enough to buy land.

Meanwhile, a “New South” was emerging. The cotton kingdom was becoming industrialized. New factories and textile mills sprang up. African Americans became an important source of industrial labor, working in sawmills, mining coal, and building railroads. In 1880, 41 percent of the industrial workers in Birmingham, Alabama, were black. Thirty years later, blacks made up 39 percent of all steelworkers in the South.

Yet during the era of Southern rebuilding, known as Reconstruction, African Americans steadily lost freedoms. Discrimination flourished. New state laws across the South—referred to as Jim Crow laws, after a character in minstrel shows—supported segregation by defining the “Negro’s place” in trains, theaters, hospitals, and restaurants. These laws were the basis for racial segregation. White politicians found ways to disqualify blacks from voting. Antiblack violence—including hundreds of lynchings each year—forced African Americans to be cautious about seeking their rights. By the end of the nineteenth century, the possibility of real progress for blacks was sadly remote.