Chapter Fifteen

America’s racial, ethnic, and religious minorities had helped fight the country’s enemies in Europe and the Pacific during World War II. Now they faced a different battle at home: the battle against discrimination. Out of the war came calls for change. In the decades after the war, a cascade of presidential decisions and new laws changed conditions for America’s racial and ethnic minorities, moving the nation closer to social justice for all.

One of the first changes took place in 1948. Three years after the war ended, the US armed services were still segregated by race. That was unacceptable to a black civil rights activist and labor leader named A. Philip Randolph, who had been calling for an end to discrimination in the military.

Randolph met with President Harry Truman to push for equal rights and equal treatment for blacks and whites in the nation’s military. Pointing out the unfairness of letting blacks fight without granting them equality, Randolph declared, “Negroes are in no mood to shoulder guns for democracy abroad, while they are denied democracy here at home.” Facing the possibility of a large protest march by African Americans, Truman issued an executive order requiring equal treatment and opportunity for everyone in the armed services.

Japanese Americans Raise their Voices

Like other Japanese who were living in California before the World War II, Kajiro and Kohide Oyama had spent the war as prisoners in one of the US government’s internment camps.

When the Oyamas were released from the camp, they returned to California and asked the courts to overturn the state’s Alien Land Law of 1913, which prevented them from owning property in their own names because, as non-white immigrants, they could not become citizens. The Oyamas had owned land in the name of their young American-born citizen son, but while the Oyama family was being held in the internment camp, the state had tried to seize the property.

The Oyamas took their case all the way to the US Supreme Court. In 1948 the Court decided that California had acted illegally in trying to take over the Oyamas’ land. Justice Frank Murphy described California’s Alien Land Law as “outright racial discrimination.” This paved the way for California’s state supreme court to declare the Alien Land Law unconstitutional in 1952.

By that time the United States had passed another major milestone in its multicultural history. In 1952, under pressure from lobbying groups that included Japanese American war veterans, Congress did away with the part of the Naturalization Act of 1790 that said only “white” immigrants could become US citizens. Now immigrants of any skin color could seek citizenship.

By 1965, about 46,000 Japanese immigrants had taken their citizenship oaths. Many were elderly and had lived in the United States as noncitizens for decades. One of them, Kioka Nieda, rejoiced in poetry:

Going steadily to study English,

Even through the rain at night,

I thus attain,

Late in life,

American citizenship.

For Japanese Americans, one more ghost still had to be laid to rest—the memory of the mass internment during World War II. For years many Japanese Americans carried that burden in silence. By the 1970s, however, the third generation wanted to break the silence. They asked their elders to tell them of their experiences during the war, and they organized pilgrimages to the camps.

Japanese Americans began asking for congressional hearings to make their voices heard. As a result of the hearings, in 1988 Congress passed a bill that officially apologized for the internments and awarded $20,000 to each survivor. When President Ronald Reagan signed the bill into law, he admitted that the US government had committed a serious wrong. Reagan pointed out that Japanese Americans had remained “utterly loyal” during the war and called the internment “a sad chapter in American history.”

Protest in the Barrios

The winds of protest also swept through the nation’s Mexican American neighborhoods, or barrios. After the war, Hispanics felt more than ever stung by discrimination when restaurants, stores, and other businesses refused to serve them on an equal basis with white customers. “We knew this was totally unfair,” said Juana Caudillo, who had spent the war years in a job related to national defense, “because we had worked hard to win the war.”

Mexican Americans who had served in the war were determined to be victorious over discrimination at home. They founded a civil rights organization called the GI Forum in Corpus Christi, Texas, in 1948. Membership grew rapidly. Within a year the GI Forum had more than a hundred chapters in twenty-three states. In addition to organizing a boycott of a company that discriminated against Hispanics in employment, members of the GI Forum called for bilingual education, with classes taught in both English and Spanish.

The war had changed Mexican Americans, turning some into activists. When a veteran named Cesar Chavez returned from the battle against fascism, he dedicated himself to the struggle of farm workers. His mission was to combat prejudice and win decent wages for Mexican American agricultural laborers, the people who picked the nation’s crops of grapes and lettuce in California and many other states.

Women shared the Mexican American desire for change. As one of them explained:

When our young men came home from the war, they didn’t want to be treated as second-class citizens any more. We women didn’t want to turn the clock back either regarding the social positions of women before the war. The war had provided us the unique chance to be socially and economically independent, and we didn’t want to give up this experience simply because the war ended. We, too, wanted to be first-class citizens in our communities.

Determined to fight discrimination, Mexican Americans wanted to end the practice of segregated education, which meant putting students of different races into separate schools or classrooms. In 1946, in the case of Mendez v. Westminster School District of Orange County, the US Circuit Court of Southern California ruled that segregating Mexican children in school violated their right to equal protection under the law, as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. This victory went beyond the Mexican American community. It led California to repeal a law under which school districts had segregated Chinese, Japanese, and Indian children.

The Civil Rights Movement Begins

The Mendez case paved the way for a historic US Supreme Court decision in 1954. In the case known as Brown v. Board of Education, the court ruled that racial separation in schools was unconstitutional. The decision applied to all public schools in the nation. Segregation, or racial separation, would be replaced by integration, the mixing of races on an equal footing.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had presented the argument against segregation to the Supreme Court justices. The group greeted the ruling as a victory for all of the American people, and as a sign that the United States deserved to be the leader of the free world. Thurgood Marshall, a lawyer for the NAACP who later became a Supreme Court justice himself, had been certain that after the bravery and patriotism that African American and Japanese American soldiers had shown in World War II, Americans would have to respect the country’s black and Asian citizens as the equals of whites.

But although the Supreme Court had made racial integration in schools the law of the land, integration remained largely a court ruling on paper. Years would pass before the nation’s school districts would put it fully into action. In the meantime, pressure for change would come not from the courts but from a people’s movement for civil rights.

That movement was born in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, when an African American woman named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus to a white man. She was arrested. Parks was not the first African American to challenge segregation on public buses in the South. Others, including teenagers, were also protesting discrimination in this way. Parks’s arrest, however, triggered a large protest: a boycott in which the city’s black population refused to ride the buses.

A young black minister named Martin Luther King, Jr. organized the protest. King had seen that although about half of the residents of Montgomery were black, most were limited to working as domestic servants or common laborers, and all were walled in by segregation in schools and on buses. His inspiring leadership of the bus boycott helped make him a leader in the civil rights movement that was taking shape across the South.

“I Have a Dream”

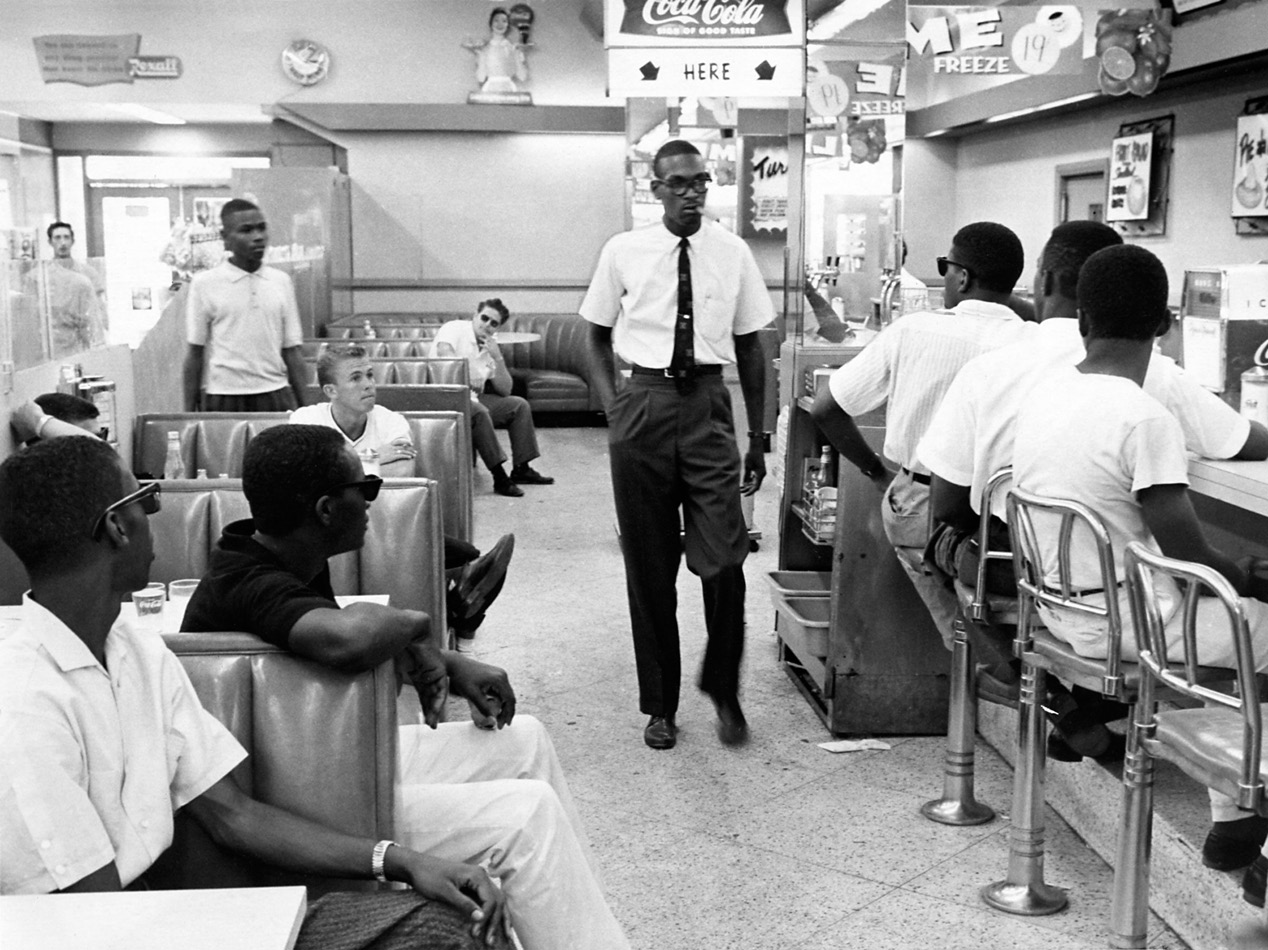

The civil rights movement challenged segregation through direct action. Confrontations occurred in Greensboro, North Carolina, when black students sat at a drugstore lunch counter that had a “whites only” policy. Under the leadership of a group called the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), similar sit-ins took place in dozens of cities and towns.

These actions did not just end segregation at lunch counters. They brought an enormous growth in pride and self-respect among the young people who participated. “I myself desegregated a lunch counter, not somebody else, not some big man, some powerful man, but me, little me,” said one black student. “I walked the picket line and I sat in and the walls of segregation crumbled. Now all people can eat there.”

“Freedom rides” soon followed, organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). In these acts of civil disobedience, black and white civil rights supporters defiantly rode together in buses into Southern bus terminals. There they were sometimes yanked from the buses and brutally beaten by racist white mobs in front of television cameras. Medgar Evers, the leading black civil rights activist in Mississippi, was murdered in 1963.

Sit-in at a whites-only lunch counter in

St. Petersburg, Florida, around 1960.

The summer of that year brought the famous March on Washington. Two hundred thousand people gathered in the nation’s capital to demand equality for all. The crowd massed near the Lincoln Memorial, which honored the president who had delivered the Gettysburg Address a century earlier, and who had freed the slaves with his Emancipation Proclamation. There Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke to the marchers, the nation, and the world, sharing his vision of freedom in America:

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. . . ., I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. . . . I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal. . . .

Blacks and Jews

Joachim Prinz also spoke at the March on Washington. Prinz was a rabbi—a leader of a Jewish congregation—who had survived the death camps of Nazi Germany. He told the crowd that the most urgent problem of racial injustice was not hatred or prejudice. It was silence. Onlookers who witness injustice and do nothing, Prinz warned, are morally guilty, for they allow injustice to continue.

Freedom riders make a test trip into Mississippi, 1961.

Prinz’s presence at the March on Washington showed the alliance that existed between African Americans and Jews in a civil rights movement that was racially mixed. Marchers and protesters sang, “Black and white together, we shall overcome someday,” and indeed, whites were involved in the movement. More than half of them were Jews. In addition to taking part in events such as the freedom rides, Jewish civil rights supporters provided financial aid and legal services to the NAACP, SNCC, CORE, and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Three civil rights workers working to register black voters were murdered in Mississippi in the summer of 1964. James Chaney was African American; Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were Jewish American.

Some Jewish Americans joined the crusade for justice for African Americans because they remembered the persecution and violence they or their parents had experienced in Russia. They saw that racism and anti-Semitism were much alike, and that both blacks and Jews had much to gain by ending discrimination.

The black-Jewish alliance fell apart, however, when the focus of the civil rights movement shifted from the lunch counters and bus stations of the South to the cities of the North. Economic and class divisions existed between Jews and northern urban blacks.

Jews owned about 30 percent of the stores in black communities such as Harlem in New York City and Watts in Los Angeles. During race riots, blacks looted those stores along with others. Many ghetto blacks also noticed that their landlords were Jewish, and they questioned whether blacks could work with Jews when Jewish property owners were exploiting black tenants.

At a deeper level, the split between African and Jewish Americans reflected differing visions of equality. The civil rights movement had begun as a struggle for black equality through integration. Success meant equal treatment for the races, first at schools, lunch counters, and bus stations, then in equal opportunity for voting and jobs.

Starting in the mid-1960s, though, young militant blacks like Stokely Carmichael and Malcolm X raised the call of Black Power. They believed that blacks, united by race, should determine their own fate. There was no place for whites, including Jews, in this movement for black liberation.

But the civil rights movement, made up of blacks and whites together, had won important victories. In 1964 and 1965, Congress passed laws and President Lyndon Johnson signed executive orders that outlawed discrimination in public accommodations (such as hotels and buses); established a commission to promote equal employment opportunity; removed obstacles such as literacy tests that were designed to prevent blacks from voting; and required companies that worked for the federal government to make special efforts to hire minorities. The result of these changes was a different America, one in which discrimination was no longer woven into law and habit.

Economic Inequality

The civil rights movement, however, could not overcome all of the problems faced by African Americans. Laws and court orders could end discrimination, but they could not end poverty. African Americans had won the right to sit at a lunch counter and order a hamburger—but many did not have the money to do it. And while the law now made it illegal for employers to show racial discrimination in hiring, salaries, or promotions, blacks saw that jobs for them were scarce.

Riots in Watts in 1965 highlighted the anger and frustration that many blacks felt. Malcolm X, born Malcolm Little, expressed this frustration when, after firsthand experience of ghetto life, drugs, crime, and prison, he said, “I don’t see any American dream. I see an American nightmare.”

The nightmare continued, and so did the violence. Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965, two years after President Kennedy was slain by an assassin’s bullet. Race riots exploded throughout the late 1960s in cities such as Detroit, Chicago, and Newark. The year 1968 brought two more shocking assassinations: Martin Luther King, Jr., the foremost symbol of the civil rights movement, and Robert F. Kennedy (brother of the president), who as attorney general of the United States had been a strong supporter of civil rights. Bombings were also carried out in the late 1960s and early 1970s by a group called the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), a violent offshoot of the student antiwar and civil rights movements.

Meanwhile, the civil rights movement had hit the walls of an inequality that was based on economics as well as on race. Beginning in the 1960s, black America became deeply splintered into two classes. The middle class experienced gains in education and income, while the “underclass” was mired in poverty and unemployment.

Plants and offices had migrated to the suburbs, putting jobs out of reach for many urban blacks. Factories closed as manufacturing jobs were moved offshore to other countries. This further reduced employment opportunities for black workers, who had been heavily concentrated in the automobile, rubber, and steel industries. Many of the jobs that remained available were low-wage service jobs, such as working in fast-food restaurants, that led nowhere.

Economic inequality made America’s inner cities into explosive places. One of the worst explosions erupted in Los Angeles in April of 1992, after four white police officers who had violently beaten a black man named Rodney King were found not guilty of the charges against them. Racial rage engulfed the city. Thousands of fires burned out of control, looting was widespread, and losses totaled $800 million.

Out of the fires, however, came an awareness of multicultural connectedness. Social critic Richard Rodriguez said, “The Rodney King riots were appropriately multicultural in this multicultural capital of America.”

Pointing out that the riots revealed tension between African Americans and Korean store owners, and that many of the looters who had been arrested were Hispanic, Rodriguez concluded, “Here was a race riot that had no border, a race riot without nationality. And, for the first time, everyone in the city realized—if only in fear—that they were related to one another.”

In 2008 the United States reached another multicultural milestone when, for the first time, the American people elected a nonwhite president: Barack Hussein Obama, the Hawaiian-born son of a white American mother and a black father from the African nation of Kenya. In spite of this sign of progress, race remained a thorny issue in national life, and economic inequality continued to plague a larger share of blacks than whites. At the same time, an economic downturn for the nation and the world meant shrinking opportunities for millions of people of all races.