Axl Rose felt at home on St. Mark’s Place in Manhattan’s East Village. He could feel the inspiration that drove his heroes, the Ramones and the New York Dolls, to create some of the most intense music he’d ever heard. Music that to this day—February 2, 1988—still spoke to the angry young man in him. Squalor, crime, and grime. Punk rockers, skinheads, and hippies hanging on for dear life. Homeless people, drag queens, junkies, and tourists. St. Mark’s was a low-key bohemian bazaar of countercultures clashing up against one another in the form of hard-to-find books, harder-to-find records, and imported porn. Studded belts, Dr. Martens boots, leather for days, and other edgy, irreverent fashion items unavailable to the rest of America like that CHARLIE DON’T SURF T-shirt hanging in the window of Trash and Vaudeville. The one with Manson’s 1969 mugshot—big and intense—emblazoned across the front. Axl thought it was killer, so he popped into the store and had the dude with the peroxide hair and Iggy Pop tattoo behind the counter grab it for him. Axl wouldn’t wear it onstage that night, though. No, he had his Thin Lizzy shirt teed up for that.

The show, later that evening at the Ritz, a couple blocks north of St. Mark’s, was being broadcast live on MTV, and Axl’s band, Guns N’ Roses was wired tight for maximum rock ’n’ roll. America took notice. When it aired, the show was watched by a relatively small audience of American teenagers, up way past their bedtimes. But the show was recorded on dusty VHS tapes and passed around high school corridors repeatedly over the coming months until the ferocity of Guns N’ Roses was recognized and salivated over en masse by high school kids everywhere.

Axl Rose came to life onscreen as a real-life version of The Breakfast Club’s Johnny Bender. He was the high school burnout who we all knew growing up. The one who doubled down on shop electives and wore ripped jeans out of necessity, not out of a sense of fashion. The guy who sported self-imposed cigarette burns on his muscular forearms and was rumored to have a Bud Man tattoo on his ass. This was the same dude who sat in the back of the classroom and simultaneously frightened and attracted the cheerleaders. Those same cheerleaders who wouldn’t give you the time of day. You saw this dude standing alone—quiet—at the edge of the keg party up off the train tracks. You left him alone because you heard the story about the time he busted the bottle of Michelob across the jock with the big mouth’s face, but inside you burned to know more about him. What made him tick? What made him so pissed? What made him so fucking cool?

Just like that kid, Axl was filled with contempt and untapped confidence. Onstage at the Ritz, you could feel his anger. It was something that had been building up inside since birth. It was coming out one way or another. Likely through violent rage or petty crime or both. But rock ’n’ roll saves. Otherwise Axl Rose would likely have been in jail on that night instead of blowing the minds of all in attendance as well as everyone watching at home on television and later on Memorex.

Onstage, Axl looked a little older than the millions of high school burnouts who would soon come to worship him and his band. He was essentially the same angry young man he was growing up back in Lafayette, Indiana, but at the Ritz, it was clear that his time had come. And he’d arrived with a murderer’s row of bandmates: Slash, the bronzed Mad Hatter Adonis; Izzy Stradlin with his “Ronnie Wood via Johnny Thunders” cool; Duff McKagan, eleven feet tall and oozing punk rock sex and excitement; and last, the wide-eyed ball of heavy metal puppy dog charisma, Steven Adler. A band that you could immediately tell never had a fuck to give. And their live show was flawless—even with the flaws, it was flawless. Songs like the Diddley-esque “Mr. Brownstone,” the jet-fueled “Nightrain,” and the showstopper “Rocket Queen” veer from brilliant to trainwreck and back again in the time it takes to suck a Marlboro red from first flame down to toxic filter.

GNR was from the street and for the street. Their lyrics represented a band living a hand-to-mouth life of rock ’n’ roll debauchery and all too willing to let themselves die in the pursuit of it. You couldn’t tell if they were creatively brave—risking it all in the service of making totally authentic rock ’n’ roll—or if they were just too stupid to know any better. Through it all, the band was impossibly cool. Every shot. Every pose. Every note (even the out-of-tune ones from Slash), every vocal (even the ones from Axl that run out of breath), all combined to somehow make them seem even cooler. If you tried, you couldn’t have created a more representative version of a rock ’n’ roll band than the one Axl Rose took to the Ritz stage on February 2, 1988. You wouldn’t know it from watching them, but that band, and the fuck-all attitude that propelled it, and more specifically its singer, had been a long time in the making.

Young Axl Rose, juvenile delinquent.

The crack from the back of the hand to his mouth came quick. It was unexpected. And it stung like a motherfucker. Young Axl could taste his blood bubbling up from his lip. The damage could have been worse, but luckily Axl’s dad didn’t wear rings. Jewelry was too ostentatious for a Pentecostal. So was Barry Manilow and his No. 1 hit, “Mandy,” which was what put Axl on the receiving end of another blow to the grill. Axl made the mistake of absentmindedly singing along to the song’s chorus with its lyrics that his dad somehow considered sexually suggestive. Axl seriously did not understand how he was related to this dude, his old man, this abusive, religious nutbag. But that was because Axl wasn’t actually related to him. He just didn’t know it yet. Then again, young Axl Rose didn’t know much beyond Led Zeppelin riffs, Elton John melodies, and pent-up rage for the man he thought was his father.

Soon, young Axl would learn that his father was really his stepfather and that his real father was never to be brought up. It was a discovery that did little to endear Axl to his stepdad, and thus the violence continued. It wasn’t reserved for just Axl, either. His stepdad threw his fists around to keep Axl’s mom in line as well. Axl saw it all as a little boy and a teenager: the beatings and the mental anguish.

By the time he was sixteen, rock ’n’ roll was his only salvation. That and his new friend Izzy. They vibed on the Stones, AC/DC, Aerosmith, and the new onslaught of British punk bands invading America: the Sex Pistols, Generation X, and the Clash.

They also bonded over beer, grass, and pills. And of course, the two of them, especially Axl, took every opportunity possible to fuck with the local authorities. Axl had a real hatred for the small-town, conservative, square-jawed local cops. To him, they were just an extension of the repression and bullshit rules imposed by his stepdad, except out on the street he could talk back and let loose the inner rage he carried. An arrest for disturbing the peace was worth it. He could never let loose on his stepdad like he could on the cops. Plus, the cops would have to catch him first. So Axl mouthed off to Lafayette’s Finest every chance he got, and the cops, in turn, found a special kind of satisfaction whenever they could bust his ass and throw him in jail. The result was a long string of juvenile arrests for petty crimes, public drunkenness, loitering, etc.

Fucking with the cops was always fun, but music was becoming the main focus for Axl. And for Izzy. They put a little band together and played when they could, but mostly they studied and listened to the masters whenever they got the chance.

Their latest obsession was the soundtrack album from the film Over the Edge, an adolescent crime drama set in the fictional suburb of “Granada” where the town’s kids, bored and tired of being neglected by their parents and other authority figures finally rebel, setting about to destroy and terrorize their town through a fiery crime spree. He could relate to the teenage wasteland/anti-authority vibe it portrayed. Just like the kids in Granada, Axl felt neglected, ignored, and oppressed, and was compelled to vent his unhappiness through violence. Plus, the movie’s soundtrack was the shit: Cheap Trick, Van Halen, the Cars, Jimi Hendrix, and even that ballad at the end, the one by Valerie Carter that played while the kids were bused off to juvenile hall—it was all right up Axl’s alley.

But Axl wouldn’t be shipped off to juvie. He’d soon be on a bus headed for a different kind of jungle altogether: Los Angeles, California.

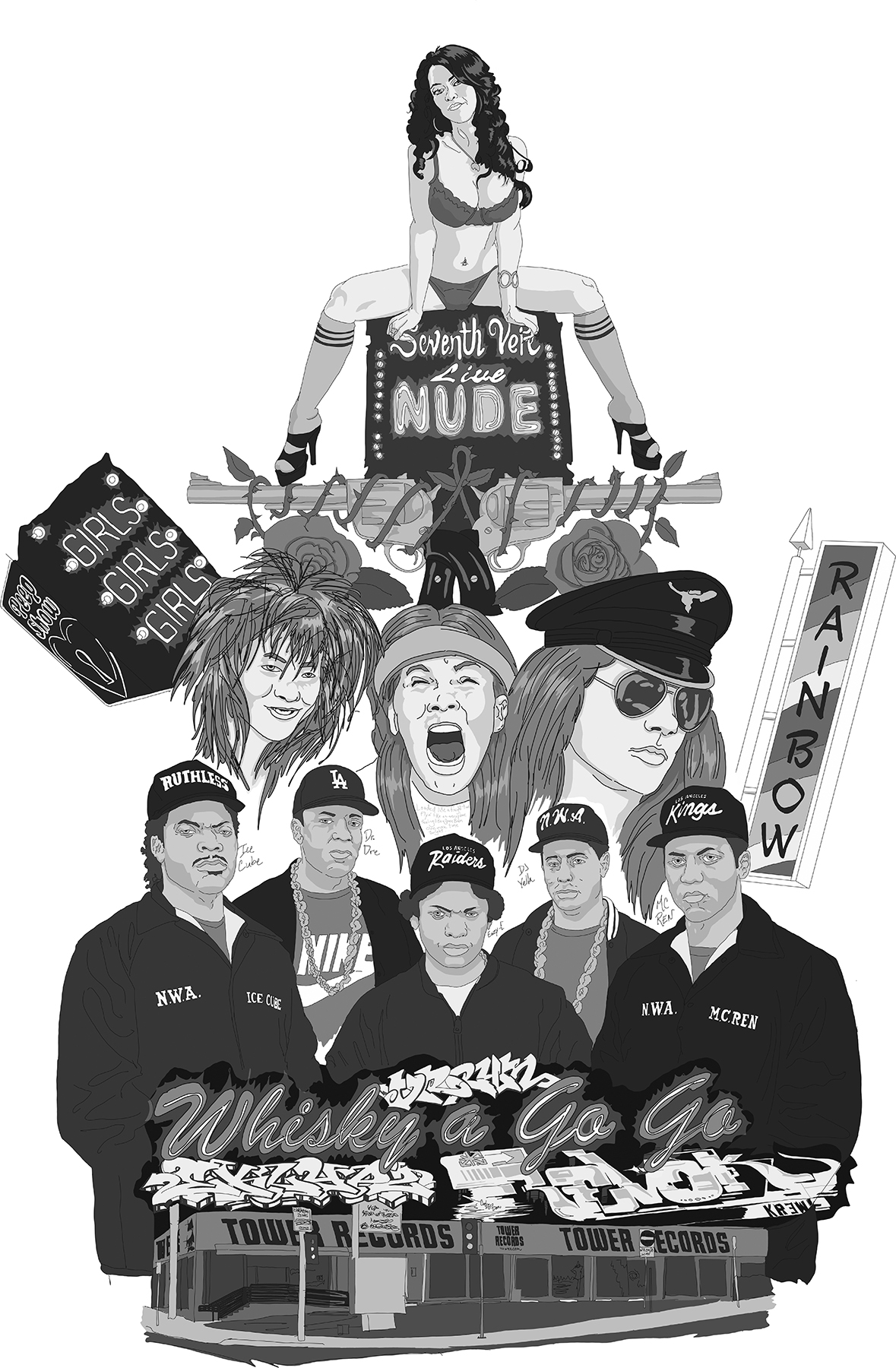

In the mid-1980s, on the side of Los Angeles where a mile-and-a-half stretch of Sunset Boulevard curves through West Hollywood and is known as “the Strip” or “Sunset Strip,” a new kind of heavy metal was doing everything it could to put LA on the musical map: glam metal.

Glam metal took its musical cues from British glam rock; the sounds of bands like Sweet, Slade, T-Rex, and Mott the Hoople traded on big, crunchy guitar riffs, deep-pocket grooves, sex-laden vocals, and hedonistic lyrics. British glam rock was a sophisticated kind of cool that owed much to David Bowie and Queen, but its American offshoot, glam metal, kept one foot planted in the concrete jungles of Iggy Pop and Alice Cooper while peacocking through the glitzed streets of Los Angeles. Fashion threaded the two styles together, but the U.S. version was more masculine, tougher, and a touch violent. LA glam bands like Mötley Crüe would meld the androgyny of Marc Bolan with the apocalyptic look of Mad Max. The result was something wildly unique and somehow representative of the violence tearing through the streets of Los Angeles at the time.

In 1985 violent crime in LA exploded to unprecedented levels due to the city’s heavy trafficking of crack cocaine. You couldn’t avoid the headlines if you tried, but glam metalheads did their best to ignore the harsh reality enveloping their city by setting up their own bacchanalia on Sunset, where every night they drank, drugged, and fucked away their worries to the sounds of the Strip’s hottest bands at the time: W.A.S.P., Ratt, Poison, and the aforementioned Mötley Crüe. There was no mistaking what LA’s new music scene was all about: debauchery. And their fans loved it. They showed up every night en masse, packing clubs like the Starwood and the Whisky a Go Go to get a glimpse of the hedonism up close and personal. Glam music was an escape from reality, unlike the music being made on the other end of town.

Down in South Central Los Angeles, where the effects of the crack epidemic were being felt most severely, rap music—up until that point mostly an East Coast export—was taking on a new identity, one that mirrored the harsh circumstances of Los Angeles street life. It would come to be known as “gangsta rap,” and where LA’s glam ran from reality, LA’s gangsta rap ran straight toward it and smacked it in its mouth with the butt of a Glock.

In Compton, about twenty miles south of the Strip in Hollywood, a local drug dealer named Eric Wright watched his cousin get shot and killed over a drug beef and decided it was time to find a new job. He took the quarter million in cash he had stashed from selling coke and invested it into the formation of a new record label with a music promoter named Jerry Heller. They called the label Ruthless Records, and Eric started calling himself “Eazy-E.” After releasing a record under his own name, Eazy formed the group N.W.A. with producer and rapper Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, MC Ren, and DJ Yella. N.W.A., along with the rapper Ice-T, would force America to pay attention to their neighborhoods that were being destroyed by drugs and violence. Streets where their neighbors clashed violently with police, who were supposedly there to protect them, frequently and oftentimes to deadly ends.

The beats these LA rappers made were bigger than anything from the East Coast and the lyrics they spat out were more direct, honest, and profane than anything anyone had heard in music before, anywhere.

And Axl Rose loved it. All of it. Mid-1980s LA music was as fraught with tension and manic energy as he was. It was bipolar. On one end, a low-down slap of unforgiving reality; a gut punch to authority. And on the other end, a high-flying, endless party; distraction via debauchery. He could appreciate the scene up on Sunset, but in his heart he knew that there wasn’t one band among them who could fuck with what he and his new bandmates were about to bring to the party.

Axl Rose, product of Los Angeles.

Once Axl Rose arrived in Hollywood from Lafayette, Indiana, the transformation from small-town delinquent to streetwalking cheetah was quick. After a few false starts and along with his hometown bud, Izzy, Axl formed Guns N’ Roses.

Out on the streets and in the clubs, the band quickly developed a reputation as the nastiest hard rock ’n’ roll band on the Sunset Strip. Let those other LA bands call themselves “glam.” Guns, or “GNR,” was going to stand out in the scene by separating themselves from the scene. They weren’t “glam,” they were “hard.” And they weren’t “metal,” they were “rock.” Hard rock. A simple but novel distinction to bring to the stage on the Strip. And offstage, Axl, Izzy, and their new bandmates, Slash, Duff, and Steven, lived the life authentically: They drank and drugged harder than Mötley Crüe. They fucked more strippers than Poison. They got into it with the LA County Sheriff’s Department whenever they could and were quick to brawl with posers, yuppies, squares, or whoever else got in their faces. They were the real deal.

And their songs were great. Totally authentic, and as such the band’s appeal was undeniable. They packed them in at the Troubadour, the Starwood, and the Whisky. In 1986 GNR signed to Geffen Records, despite fears from executives that the band would be dead before their record was even released. The thinking among Geffen employees was that if the drink and drugs didn’t get them, then they’d self-destruct via Axl’s wild temper.

The band was generally a mess. They were basically homeless. Guns N’ Roses squatted in their rehearsal space. A one-car-sized storage unit off Sunset Boulevard behind the Sunset Grill. They slept among their gear. There was no kitchen and no bathroom. But there was a constant party. When not rehearsing, which they did constantly, they’d get high and get drunk on Nightrain with the whores from down on Hollywood Boulevard, and party with members of Faster Pussycat, Redd Kross, and Thelonious Monster.

Soon young kids from the Valley started showing up to listen to the band rehearse. Steven and Slash would play nice for a bit and scam them out of their money under the guise of procuring drugs for them. Axl didn’t have time for such pretenses. He would just roll them for whatever cash he could get. Young women—valley girls and prostitutes alike—were subjected to a “Get Naked or Leave” policy. The fucking would spill out into the alley, and while little suburban valley boys realized their fantasies and got with the professionals from Hollywood and Vine, the guys in the band would empty their pants pockets for their cash and clean out the purses of the less-suspecting prostitutes.

Word on the strip spread: There was a party going on. And it was wild.

One time, Don Henley from the Eagles showed up. Impressed and horrified by the debauchery, Henley was moved to write “Sunset Grill,” a song he would include on his second solo album:

You see a lot more meanness in the city

It’s the kind that eats you up inside

Hard to come away with anything that feels like dignity.

Their party grew. The band was sounding great but still wasn’t making any money, so Izzy started slinging dope to bring in cash. People were talking; Guns N’ Roses were fucking nuts and their parties were awesome, plus they had great heroin. Eventually, even Izzy’s hero, Aerosmith guitarist Joe Perry, showed up to score.

There were too many scantily clad spandex prostitutes and groupies to count, and telling them apart from one another was becoming a real problem for Slash. When it came to women, Slash was largely indiscriminate, but he did like the good girls; they usually had apartments he could crash at, and those apartments had running water and toilets.

The party raged, and soon enough the West Hollywood sheriff’s deputies started coming around to restore order. Axl would give ’em lip, and the next thing you knew, he’d be bent over, face smashed sideways on the hood of a cruiser, his wrists cuffed behind him. They’d either haul him in or smack him around or sometimes both. It was just like the old days in Lafayette. Nothing had really changed, and why should it have? Axl was no less pissed off.

Violence followed the band wherever it went. Bar fights, alley fights; they were the rule, not the exception. Even jumping off the stage midset to crack a wiseacre in the grill was fast becoming just part of the gig for members of GNR with Axl at the helm. The band took no shit.

Ever.

On July 21, 1987, the band’s debut album, Appetite for Destruction, was released. Their star started to slowly rise, but growing fame didn’t curtail the band’s behavior. It only intensified it. Newfound celebrity and notoriety started to create a sense of isolation for Axl. A feeling that his lyrics for “Out ta Get Me” were a self-fulfilling prophecy:

Sometimes it’s easy to forget where you’re goin’

Sometimes it’s harder to leave

And every time you think you know just what you’re doin’

That’s when your troubles exceed.

Axl wrote it mainly about Lafayette, but increasingly it seemed to be about the people around him now. Wherever he went, he believed, they were trying to keep him down. Just like authority figures back home, nowadays the cops, the record label, the promoters, and increasingly the press were trying to bleed out of him what it was that made him special in the first place. To get him to tone it down. To conform to their bullshit.

It was making him paranoid. And causing very dramatic mood swings. The mood swings were always there, but when the band was starting out, they’d derail a rehearsal or a party. Maybe a show. But as the band grew, so did the stakes, and mood swings at this stage of Axl’s career were much harder for everyone to deal with.

In February 1988, just after their triumphant show at the Ritz in NYC, Guns N’ Roses embarked on their first headlining tour. It was a big deal. And Axl was a big mess. He was jankier than usual and emotionally volatile. Some believed it was because of his relationship with girlfriend Erin Everly (daughter of rock ’n’ roll royalty, Don Everly, one half of rock ’n’ roll pioneers the Everly Brothers), but it was more likely that Axl’s intensity was simply increasing in proportion to the growing stature of his band.

On February 12, for unspecified reasons, Axl blew off one of the band’s first headlining shows in Phoenix, Arizona. He went missing. No one knew where he was. The second show in Phoenix, the next night, was also canceled. The band was immediately bounced by promoters from an upcoming opening slot on the highly coveted David Lee Roth tour. Further, they were eliminated from consideration for the opening slot on the even more highly coveted Jimmy Page tour. Opportunities that would have exposed them to larger audiences. Axl’s bandmates were incensed. You don’t pull a no-show. Not in the music business. It’s a death sentence. A career killer. They contemplated kicking Axl out of the band for the offense. He had little contrition and less in the way of an excuse. He simply didn’t show. And he simply didn’t care if they wanted to kick him out of the band. Go ahead, he told them. Who are you going to get to replace me? He knew his place in the band was secure, but not without one major concession. Axl had to agree with his band, management, and label to undergo a psychiatric evaluation.

Axl submitted to tests at UCLA Medical Center. The doctors, in their evaluation, considered not only Axl’s present state of almost constant emotional volatility but also the oppressive childhood that he detailed for them along with his twenty arrests. He presented a clinical diagnosis of manic-depressive disease, or what is commonly referred to today as bipolar disorder.

It made sense to Axl. And the prescribed lithium helped at times, but there was little he could do to completely quell the beast within. The mood swings continued. Bandmates weren’t the only ones subjected to them. Fans and civilians weren’t immune from the swings in mood that would sometimes escalate to full-on violent outbursts.

Axl beat a businessman senseless in a hotel bar for calling him a “Bon Jovi look-alike.”

He nearly baited eighteen thousand fans into a full-scale riot at the Philadelphia Spectrum, fighting with the local cops patrolling the crowd because he thought they were harassing him before the show.

He was arrested for cracking his female neighbor over the head with a wine bottle because she complained about the noise.

The press took note. And bad press began popping up. So Axl added the media to his shit list. Second to the cops and third to his fucked-up stepdad, but prominently placed nonetheless. But nothing did more to undermine Axl Rose’s already low opinion of the press than the reaction to the events that took place during Guns N’ Roses’ set at the Donington Monsters of Rock festival.

Anticipation for GNR’s performance was peaked. Security was lax. Capacity was maxed. One hundred thousand rain-soaked bodies standing in the mud. Most of them drunk. The sun was buried behind dark, ominous clouds. The band knew something was wrong and began their set with trepidation. It mattered little. The crowd went apeshit. Barely into their second song, the audience lurched forward as one giant wave. Then a hole in the middle of the crowd opened up. Within seconds, bodies were sucked into an undertow of humanity. A massive mosh pit began. Izzy freaked out and stopped playing. The rest of the band followed suit. Axl tried his best from the front of the stage to chill the crowd out. Bodies began to be pulled out of the muddy melee, injured and in need of medical attention but alive. Once it looked as though order had been restored, the band kicked back into their set with “Paradise City,” and shit got real. The crowd’s moshing became violent and relentless. Thousands and thousands of people were worked into a fit, slamming wildly into each other to the sounds of the most dangerous band on the planet. The crowd swayed uncontrollably as one, and with a single false move it could overtake the stage or collapse in on itself at any moment. The band was frightened. They tried cooling things down with a new acoustic number, “Patience,” and then gave it one more shot with “Sweet Child o’ Mine,” but it was no use. The crowd was too intense. Too terrifying. After the tune, the band bailed. Axl spat into the mic before leaving the stage, “Have a great fucking day and try not to fucking kill yourselves.”

Little did he know, a few of them had already been killed. Later that night, in the hotel bar, the band was told that two of their fans at Donington had died. Trampled underfoot during their set. Both were so mangled they needed to be identified by the papers in their pockets and the tattoos on their bodies.

The press blamed the band. The story being printed and reprinted over and over was that GNR refused to stop playing despite the obvious danger in the air. Of course, Axl had stopped the show twice and eventually cut the entire set short. This was never reported. There was no advantage to the truth for the press. The story sold better if the dangerous junkies from Sunset Strip caught the blame.

None of this was lost on Axl. The deaths at Donington by themselves were hard enough to swallow. These were kids. Fans. And now they were dead and the press was blaming the band.

TWO DEAD AT DONINGTON, screamed the headlines. That was one more than Altamont.

His rage intensified. It seemed that whatever he did, authorities were out to get him. And the notoriety caused the band’s popularity to grow. And the more his own fame and celebrity grew, the more shit he seemed to have to take from the press, from the cops, from whoever.

He tried retreating into himself, but by now MTV had begun playing the band’s videos in heavy rotation, and their popularity skyrocketed. A new album was needed quickly to capitalize on their success, but a proper full length was impossible to put together with the band’s touring schedule (not to mention the near-debilitating heroin habits of Izzy, Slash, and Steven and the general growing dysfunction of the band as a unit). So it was decided that an EP called G N’ R Lies would be released as a stopgap. The concept was tabloid trash, a world that the band was becoming all too familiar with. The artwork was a National Enquirer–like cover that poked fun at the press and its growing fascination with the band. The music was a mix of covers and unreleased old and new tunes that the band had been working up live.

To Axl, G N’ R Lies scanned the world of celebrity decadence and tawdry gossip against a tough-talking, hard-living, unseen street reality. As a record, it was bipolar. Like his LA. Like him.

Axl saw himself as a voice for this reality. Just as he believed Eazy-E saw himself as a voice for his reality. So he was going to spare none of the details and none of the reality he’d come to learn and to live around in Los Angeles. On the song “One in a Million” he sang out:

Police and niggers, that’s right

Get outta my way.

When you first hear the N-word in the lyrics, there is a split second where your brain stops listening and you involuntarily ask yourself, “Did he really just say that?” and then, as if to answer your internal monologue, Axl immediately follows up the N-word with, “that’s right” as in, “Yeah, motherfucker. I just said that. So what?”

Understandably, the press lost its collective mind. Axl was quickly labeled a racist as well as a homophobe for the following lyric, also from “One in a Million”:

Immigrants and faggots

They make no sense to me.

The backlash was immediate. Radio refused to play the song. Billboard magazine excoriated the band. Certain promoters refused to market the record. Popular comedian Bobcat Goldthwait accused the band of writing the song just for the publicity. Vernon Reid, guitarist for Living Colour, a chart-topping African American rock band whose very existence (and success) challenged ideas around race in the music industry at the time, and fan of GNR, called Axl out publicly as well.

Axl claimed that the song was about a real-life experience he had at a bus station in Hollywood. It was reality and therefore, in his mind, worthy of documenting. However, the actual reality was that Axl was leveling a haymaker at the press, who he must have known would react intensely in response to his highly offensive lyrics. It was the sixteen-year-old in Lafayette lashing out but this time at a bigger strawman and under a much bigger spotlight.

But somehow, none of it mattered. The album was an immense seller.

Album sales weren’t negatively affected, but the intensity of the public backlash was almost unbearable for Axl. He grew more manic. And then more depressed. He doubled down on therapy and through analysis uncovered “recovered memories” of sexual abuse as a child. He claimed publicly that he had been sexually assaulted by his real father who had, as Axl was now able to remember, raped him as a two-year-old. With psychotherapy, Axl felt himself making progress, but toward what he didn’t exactly know. A torrent of pain, shame, and high-pitched anger raged inside of him stronger and more intensely than ever before, and he was about to blow.

Backstage at the Riverport Amphitheatre, in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1991, Guns N’ Roses cooled their jets. You could tell just by looking at them that they were one of the biggest rock ’n’ roll bands in the world. But the band Axl Rose had started back in Los Angeles six years earlier had begun to fade away. This band assembled before him, half-assedly working out its preshow jitters was a damaged, barely functioning version of its prefame self. Three years of hardcore drug and alcohol addiction and high-stress offstage drama had resulted in their current state.

Slash lived in constant fear of dying of AIDS. He believed there was a coming LA Metal AIDS epidemic and that if he or David Lee Roth caught it, then it was all over; the entire metal scene would be wiped out. His band members most definitely included. Slash was also desperately trying to kick heroin under threat from Axl to quit the band if he didn’t. He was chipping occasionally, but for the most part he’d had it under control ever since Axl, while opening for the Rolling Stones onstage at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, threatened to quit the band, saying to the audience, “Unless certain people in this band…get their shit together…these will be the last Guns N’ Roses shows you will fucking ever see. ’Cause I’m tired of too many people, in this organization DANCING WITH MISTER GODDAMNED BROWNSTONE!”

Unlike Slash, Izzy got the message. It was a combination of Axl’s threat and seeing his hero, Stones guitarist Keith Richards, up close and personal cheating death throughout middle age. What were the odds that a second Chuck Berry–obsessed guitarist in one of the world’s greatest rock ’n’ roll bands would also escape heroin’s mortal grip and live to see his forties? Izzy didn’t know the answer, but he knew his odds weren’t good. So he gave up dancing with every kind of intoxicant, but as a result he now barely interacted with his bandmates and elected to travel via his own tour bus with his smokeshow of a girlfriend rather than fly with the traveling party, including groupies, on the band’s chartered plane.

Steven Adler either refused or was simply unable to give up heroin, and he was unceremoniously kicked out of the band.

Duff, depressed from splitting with his wife, had retreated into his own bummed-out alcoholic nightmare while his new bandmates, drummer Matt Sorum and newly added keyboard player Dizzy Reed, did their best to fit into the highly dysfunctional band.

A band that was under immense pressure to deliver a follow-up album that would outperform their massively successful debut. The recording of said follow-up was wrought with tension. Axl’s bandmates seldom appeared in the studio at the same time as he did, for fear of running up against his violent mood swings and thus sandbagging whatever slogging progress they’d made up to that point. The album was recorded piecemeal and at times by remote committee. The exact opposite of Appetite for Destruction, which was a short, frenetic shotgun blast of a musical statement made by five guys living the same life, dealing with the same problems and trying to get to the same place at the same time. That simplicity of intent was gone now. Axl was trying to make a grand creative statement while various members of his band were at times trying to work around dysfunctions: addiction, newfound fame, and an increasingly volatile and uncompromising lead singer.

Said lead singer sat backstage and watched his rhythm guitar player bang out the riff to Chuck Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen” on his unplugged Telecaster. The strings eventually popped and snapped themselves into the chord progression for Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel”; the version that Izzy and Axl had used to steal the show out from under Tom Petty at MTV’s Video Music Awards a few years back. Axl loved Elvis. He was the King. And Axl saw in himself some of that same ordained royalty. But Elvis was a nice boy and Axl was anything but…and he knew it. He crossed his arms and subconsciously ran his hand over the VICTORY OR DEATH tattoo on his left biceps. The yellow-and-red regimental emblem was the same design that Elvis wore on his hat in G.I. Blues. Maybe the outcome of the slogan wasn’t so either/or, though. What if you could achieve both? Victory and death?

The pure rock ’n’ roll days of the Ritz show were long gone. These days, Guns N’ Roses were a worldwide phenom. The greatest rock ’n’ roll band on the planet. Guns N’ Roses were the real deal and very nearly coming apart at the seams because of it: victory and death.

Life at the moment for Axl and the rest of the band was tense, but backstage things were calm. While Izzy fingered his guitar, Slash—oblivious—fucked with the FM dial on a transistor radio and nursed a bottle of Jack Daniel’s. Duff mixed up his hundredth vodka cranberry, his head somewhere else entirely. Matt warmed up with a drum pad; an endless triple-stroke drum roll, eighth-note triplets, then sixteenth-note triplets that were both only slightly out of time with Izzy’s riff. Matt dropped the beat indiscriminately to sip cold domestic from a can. This being St. Louis, the domestic was Clydesdale piss from the brewery of Messrs. Anheuser and Busch. Dizzy was nowhere in sight, off somewhere chasing skirt, taking advantage of his new fame. Axl was quiet, sipping champagne.

Preshow jitters time was the one time the band could stand each other’s presence. They waited. Bonded by the incredibly rare reality they were about to go through together. Something very few people on the planet ever experience; the adoration of twenty thousand screaming fans who all want to either be you or fuck you. The exact type of rare experience that can bond you together and overcome even the deepest divisions.

Axl had “One in a Million” on his mind. It had been a while since they performed it. Who needed the headache? Axl took this as a defeat of sorts. Despite the controversy surrounding the song’s lyrics, it was still a good song. Axl toyed with the idea of sneaking it into the set that night, but the thought was short-lived. It was nearly showtime, the only time of day that mattered.

GNR took the stage to a packed and rabid house. By now the band had their stage show wired tight. Axl insisted they fly by the seat of their spandex and Levis without a set list to keep it fresh, but the band did rely on a handful of sequential songs guaranteed to drive audiences wild. “Welcome to the Jungle” and then a downshift into the anthemic ballad, “Civil War.” After that, a drum solo from Matt so Axl could suck on an oxygen mask backstage, then a guitar solo from Slash into the theme from The Godfather and finally into the barn-burning “Rocket Queen” to close the show.

The crowd recognized the song the instant the drums picked up. They knew this was the closer. Their last moments of the show to dig in and enjoy, to stay transported off in that place far away from the realities of the real world, from their shitty jobs, their parents, their schools. They pumped their fists, danced, sang along, and did their best to rage with their rock gods onstage in front of them. From the blinding stage lights Axl could only see them swaying en masse. Flashback to Donington. He ripped into the first verse.

He wondered about security. Upfront it was lax. To Axl, the security staff seemed more interested in the band than in protecting the crowd. Flashback to the Philly Spectrum. Fucking Pigs.

His anger shot up through his chest and into his throat. His breath quickened. The words to the second half of the verse came out rushed and erratic.

Axl homed in on a civilian in the first couple rows. Was that a fan or a member of the press snapping photos? The press were only allowed a certain amount of sanctioned pictures per show, and the band was to be captured during set times at the beginning of their set and from the confines of the camera well up in front of the stage only, not from within the audience. Oftentimes a performer will remove a piece of clothing after the allotted period of time, so that if a media outlet runs a photo of the performer without that scarf on, or without that leather jacket, then everybody knows that media outlet broke the rules. Axl boiled. Fucking press. Give them an inch and they take a goddamn mile. The press did whatever the hell they liked. Wrote whatever the hell they wanted. Spread whatever fucking rumors they felt like spreading. They had carte blanche to fuck with you just like the pigs in Philly. Just like the West Hollywood sheriff’s deputies and most definitely just like the hick cops back in Lafayette. They were all out to get him. To take advantage of him. Just like his father had done.

As he sang out the chorus, Axl focused on the dude in the audience taking pictures. Shit. It was worse than he thought. Dude wasn’t taking photos, he was videotaping! Axl got three lines deep before it all became too much to take. He stopped singing and screamed into the mic,

“HEY! Take that! Take that. NOW. Get that guy and take that!” Axl had stopped singing completely and was pointing at the dude with the camera imploring security to stop him. Axl could see now. Dude wasn’t a member of the press. He was a biker. Nobody did anything. Axl raged at the inaction. Here he was. Helpless again. The band, confused, continued the chorus behind him.

Fuck this, Axl thought. Press member, biker, whatever. It didn’t matter. When not one member of the venue’s security team moved to help him, Axl literally flew into action. He barked into the mic, “I’LL TAKE IT, GODDAMMIT” before slamming the mic down and diving headfirst into the audience to solve the problem himself. The band, almost on cue, resolved the chorus and began muddling through an instrumental version of the second verse while their singer went at it—wildly throwing punches in the first few rows. Axl, unaware of who he was fucking with, began manically flailing and seriously pissing off members of the Saddle Tramps motorcycle club. Local security knew where their bread was buttered and went at Axl instead of at the bikers. Axl resisted. Kicking, punching at everyone in sight. When it became clear that security wasn’t helping, GNR’s roadies entered the fray and pulled Axl back up onstage, but not before he landed a full-fisted punch in the grill of one of the crowd members who’d got up in his face.

Once he was back on stage Axl grabbed the mic, pissed, and quickening his pace toward the side of the stage, “Well! Thanks to the lame-ass security, I’m going home.” And with that he slammed the mic into the stage and stormed off. Slash leaned into a mic and added a casual, “We’re outta here.”

That was it. Show over.

The crowd was stunned. Confused. No one moved. No one knew what was going on. GNR’s roadies quickly went about breaking down the band’s gear. A clear signal that the show was definitely done. The party was over. Guns N’ Roses weren’t coming back. Beer cans began raining down on the stage from the audience. The boos started. At first a smattering and then the chorus of an angry mob. The roadies were pissed and rightly so. They began to taunt the audience, inciting them even more.

Drunk, angry, and violent, the audience turned on itself. The Saddle Tramps went alpha, erupting on anyone who got in their way while making their exit. A naked man ran around the floor frantically, blood pouring from a wound in his head. The police descended to restore order and were openly challenged by fans. Beatings commenced. Batons. Steel-toed kicks to the skull. A chant of “Fuck You, Pigs” rose up from the audience.

The crowd started ripping up the chairs from the floor. Pulling them apart and launching them to the stage. The cops reeled out the fire hose and attempted to use it to beat back the crowd, but the water pressure was so weak the audience began moving toward the water to cool off and thus toward the stage. One of the giant video screens on the side of the stage was pulled down. The massive sixty-ton sound and light rig lurched uncomfortably from side to side as idiotic fans swung from its cables. Riverport was about to make Donington look like a walk in the park until the cops broke out a tear gas–like substance and got hold of the situation.

In the end it was a bloody riot that Axl Rose’s deep well of anger had incited: sixty-five people badly injured, twenty-five of them police officers. Dozens arrested, and hundreds of thousands of dollars in property damage. Axl was eventually charged with four counts of assault and one for property damage. The jury found him guilty and the judge fined him $50,000. It was worth it, Axl thought. They all had it coming.

After he stormed offstage, the band’s road crew swept into action, endeavoring to get the band away without further incident or arrest. They exited out the back under a deluge of flying glass bottles from angry fans who had by now made their way around to the backside of the venue. The tour bus was too easy a mark. And the limos were out of the question, so all six band members dove into a nondescript passenger van and hid on the floor, out of sight from the gathering mob as they made their escape.

They were traveling together again. Just like the old days back in LA. Before the fame. Before the chaos and the pressure of success. Axl was too keyed up to reflect on the irony: that his anger and mood swings that had contributed so significantly to driving the band apart as of late, were the exact things bringing them together at this very moment en route from one gig to the next. Hoping, just as they had in the beginning, to escape arrest in time to get to the stage for the next show. With a roadie behind the wheel and the band members outstretched on the floor, the van raced through the streets of St. Louis.

It was a good half an hour before they raised themselves up off the van’s floor to look out of their windows, and it was lucky they did. Izzy watched as they passed a sign for Wentzville. Wentzville was where his hero, Chuck Berry, lived. Izzy knew enough rock ’n’ roll history to realize that Wentzville was west of St. Louis, Missouri. West. The dumbass roadie behind the wheel had them heading the opposite way they were supposed to be going. They needed to be driving toward Illinois and their next gig in Chicago, home of the blues and home to another one of Izzy’s heroes, the signifying Bo Diddley, and also home of Chess Records, where Chuck Berry made his greatest records.