Phil Spector’s nasally voice sang through the crackle of the Pac Bell telephone line. On the other end, sixteen-year-old Annette Kleinbard, the singer in his group the Teddy Bears, was unimpressed. But Phil was undeterred. He hung up and beat a hasty retreat to his bedroom at 726 North Hayworth in Los Angeles’s Fairfax neighborhood, slammed the door shut so his overbearing mom would get the picture and leave him alone. He proceeded to bat the song’s chords around the neck of his Gibson acoustic guitar while the melody to the song he was trying to finish writing banged around in his brain. Finally, exhausted and having made little progress, he passed out on his fully made bed, completely clothed, guitar at his side.

The dream was intense.

It’s raining. Hard like it always is in the dream. And it’s Phil at his dad’s grave. It’s the funeral all over again but it isn’t 1949, it’s present day, 1958, and Phil is no longer a nine-year-old. He’s eighteen. As he is in real life, but unlike in real life, in his dream Phil is already a success. He’s dressed for the part of an earth-shaking music man. His style is part hepcat, part greaser. The funeral guests all know who he is, but he can’t make out their faces. Some approach him, but Phil’s bodyguards—yes, bodyguards—keep them away.

He’s staring at his father’s headstone. His mother is seated next to him. She leans over and whispers to him that she will never forgive Phil for what his father did—sucked on the end of a carbon monoxide–filled hose until the lights went out in the Bronx. The words stung. So did the grief. It overwhelmed him at times. The grief put him on an emotional wave of extremes: one moment higher than the Hollywood hills, and the next lower than the rats that scurried shamefully over the New York City street corners he spent his early childhood on. Phil held focus on the headstone and concentrated. He tried hard to make out the inscription;

TO KNOW HIM WAS TO LOVE HIM.

Phil shot up, awake, in his bed. Sweat covering his body. So much sweat that he thought for a second he’d pissed himself. No matter. He grabbed his guitar and strummed the chords to the song he was trying to impress Annette with:

Open D major. Then the trusty A7. He walked his finger up to the B minor chord, picking out the bass notes in the process. Then to the G.

Again.

And then he started singing the same line he’d sang to Annette over the phone but substituted the word was with is, shifting the tense from the past to the present and thus completely altering the song’s sentiment. It was no longer a mixed-up kid’s dark lament of a dead parent, it was relatable teenage heartache.

“To Know Him Is to Love Him,” well, that’s saying something. We all knew him, Phil thought. Or at least the girls at Fairfax High knew him. He was the guy in the hall with the letter jacket and the big smile. Kinda boring. Totally sweet. Always there when you needed him.

Phil filled in some lines over the chord progression:

To know, know, know him is to love, love, love him

Just to see him smile, makes my life worthwhile.

The chorus wasn’t for Phil or his dad. It was for them, those girls. It was all they were going to focus on, anyway.

He knew what those kids wanted: He had been studying them from the outside, looking in. Ever since his mother uprooted young Phil and his elder sister, Shirley, from the Bronx to California, he hadn’t fit in. You can take the boy out of the Bronx, but you can’t take the Bronx out of the boy, especially the Bronx accent, which in Phil’s case was filtered through an especially nasally voice. It’s never easy being the new kid, but when you’re the new kid, and your voice is the type that whatever bully coined the term pipsqueak had in mind, then it’s especially difficult. So Phil didn’t contribute. Didn’t speak up all that often. Instead, he observed, like any great writer. But Phil’s time to share his observations with his peers eventually came, and he shared through song. He would let teenage America have that chorus to themselves. It was his gift.

The verses on the other hand. They were all his:

Everyone says there’ll come a day when I’ll walk alongside of him

Yes, just to know him is to love him.

Phil was speaking to his dad. It was his way of not letting his dad leave. For everyone else it was a pop song. And it was perfect for its day, sentimental like the Pat Boone and Perry Como hits that reached back to the postwar cultural safety net that parents could easily fall into but imbued with the rock ’n’ roll backseat teenage yearning of the Everly Brothers and Ricky Nelson that made kids want to jump out of their PF Flyers. Phil, still just a kid himself, focused on the yearning part. More specifically, he focused on his lust as he lip-synced the song’s lyrics and avoided eye contact with the buxomy blond dancers swaying in the audience in front of him on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand.

Phil on guitar, beside Annette singing, was a boy brimming with lust. Since the release of “To Know Him Is to Love Him” and its chart-climbing success, the world had opened up to Phil. He sang the backups, eagerly anticipating the postshow party where he’d get up close and personal with the Bandstand dancers despite the fact that physically, he was a far cry from the Troy Donahue type he’d written about in his No. 1 single. Yes, No. 1. Suicidal grief masquerading as unrequited teenage love rocketed Phil Spector’s Teddy Bears to the top of the charts, but he still cut a diminutive figure on top of the bandstand. Five foot five, barely taller than Annette, and a square-looking haircut that wanted to be a rock ’n’ roll pompadour but instead looked like a boyish flattop, largely because of his rapidly thinning hair. He was more nerd without a fashion sense than rebel without a cause. And his outfit, more Canter’s busboy than James Dean; a lame boxy-white blazer that Phil clearly had trouble filling out, along with a flattened Western-style bow tie. Hardly the television debut of the next Elvis Presley, whose physical presence and prowess was so impressive that Phil was compelled to take the name of his group from Elvis’s recent hit “Teddy Bear” despite the fact that Elvis—unlike Phil—couldn’t write his own songs.

But Phil Spector could write his own songs. And he’d write lots after “To Know Him Is to Love Him.” Many of them would become the most culturally consequential pop songs in history and would make Phil Spector more money than he’d ever be able to spend in one lifetime. He would become a millionaire by the time he was twenty-two. And because he had made all of this money himself, he reasoned that doing everything himself was the move. Writing the songs wasn’t enough; he had to produce them as well. And since he couldn’t trust the songs he had written and produced to any old record label, he started his own company, Philles Records, after cutting his teeth as a staff producer at Dune Records. He started the label with fellow producer Lester Sill, but Phil would buy out Sill within a year. Partners were dead notes. Phil would rather bet on himself, play the open chords.

Phil was shouting over the sound of the jet’s turbo compressors and completely ignoring the flight’s stewardess. He was trying to make a point to his favorite Beatle. “Look, John, baby, you’re gonna be all right. We don’t all carry guns, okay? Besides, Kennedy couldn’t keep his little Irish schmeckel in his pants and everyone knew it, okay? You brought your wife and your baby with you. You’re gonna be fine. As long as Paul learns all the words to ‘The Yellow Rose of Texas.’”

Phil kept fast-talking John, denying him a chance to laugh at the joke.

“I’m just teasing you, Johnny baby. Don’t look at me like that. I’m telling you, you’re gonna be fine in the States. And you’re gonna be safe. Just keep your little schmeckel in Cynthia’s purse.”

“Who said anything about it being little, Phil?” John deadpanned.

Phil Spector, the so-called “first tycoon of teen” roared over the sounds of the Boeing 707 en route from London’s Heathrow airport to the recently named John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City on February 7, 1964.

He stopped and spoke to John as he paced up and down the aisles. The Beatles would later dub Phil “the man who walked to America” because he paced so much on that plane ride.

Ringo was giddy. Grab-assing with the stewardesses. George was quiet. Up front talking to the pilot. Paul was in all seriousness trying to learn “The Yellow Rose of Texas” on John’s acoustic, and John, per usual, was tense. Phil’s pacing probably didn’t help. The Beatles’ skyrocketing success in the States on the heels of Kennedy’s assassination had him worried about his band’s first trip to the United States.

So it was left to Phil Spector, the producer and songwriter of the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby,” the earth-shattering smash hit that rattled the creative cages of the most successful musicians on both sides of the pond, to convince John Lennon—one-quarter of arguably the most popular group on the planet—to cool out and get ready to enjoy himself in America. If nothing else, Phil’s own nervous energy served as a barometer for John. At least he wasn’t as high-strung as Phil.

John was listening, though. He respected Phil. Phil was smart. His talent was immense and obvious.

It’s no stretch to say that Phil Spector was a genius. One of those rare talents that created something completely new, almost out of thin air. Phil Spector’s recording style was something that had never been heard before in popular music, or anywhere else for that matter. It was a “wall of sound,” and Phil held the patent. Drawing on the massive lush orchestral sounds of classical music and funneled through the reality of having to record in tight studio confines, the result was a dense and layered sound that was exhilarating coming out of the tiny jukebox and car stereo speakers of the day.

Phil took it one step further and invented “groups” out of thin air to suit the sounds he was creating. Normally, to that point anyway, a professional songwriter would write a song. Then the song’s publisher, the record label, the hired producer, and to some extent the songwriter would find a singer or a group that was either a known commodity with an audience or a new star on the come-up whose future they were investing in. That song would then be given to the singer to record with the producer and eventually released through the record label.

What Phil did was cut everyone out of the equation. He was the first producer of note to also write the songs. And he would not be slowed or deterred by the complications of finding or working with existing stars. To Phil Spector, making music, making hits, wasn’t necessarily about the singer or the song. It was about the producer. The man who could pull the track together and craft it into a hit by any means necessary. When a singer or a group couldn’t be found in short order, Phil would just invent one. Literally. Out of thin air. We have this great song I wrote but no group to record it? Doesn’t matter—pull some backing singers in from the session down the hall, slap a name on them, something like “Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans,” get the song on tape, then wax, then ship it, get it played on radio, and voila—a top-ten hit. Oh, there’s another song, “He’s a Rebel,” being recorded over at Liberty Records and it’s got real potential but someone else wrote it? The demo sounds perfect for the Crystals, the girl group I’ve been riding up the charts with lately. The Crystals need to record it before Liberty makes it a hit first. Oh the Crystals are in LA and can’t get to NYC anytime soon for the session? Just as well. The song is a beast. The melody likely isn’t one the Crystals will be able to handle in the studio anyway. Okay, no sweat. I’ll get my girl, Darlene Love, and her group, the Blossoms, to record it on the quick. Darlene is in town and she can sing anything. Fuck Liberty. We’ll get it released before them. And you know what? Forget about the Blossoms. They’re not rocketing out of my stable of stars as quickly as the Crystals, so even though the Blossoms recorded the tune, let’s credit it to the Crystals because they’re more popular and have a better chance at success and because I’m the producer and I know what’s best and voila—a No. 1 hit.

It’s hard to argue with success. Phil’s unconventional approach to talent and recording made him the most successful pop music producer on the planet. Between 1961 and 1966 he charted more than twenty top-forty hits with acts like the aforementioned Crystals, the Righteous Brothers, and the Ronettes.

The Ronettes, for Phil, were his greatest creation, and their smash hit “Be My Baby” made him in the eyes of many of his contemporaries. Not only was it a hit upon its release in 1963, its sound was groundbreaking. If ever there was a recording to define the “wall of sound,” it was “Be My Baby.” The recording relied on a mass of instrumentation: the biggest of beats with multiple guitars, pianos, and horns all layered on top of one another, and Phil’s favorite new young female singer, Ronnie Spector, sailing over the top of it all with her sultry vocals.

The song hit No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 and was unavoidable in 1963. The Beatles were obsessed. As were the Rolling Stones, whom Phil and the Ronettes had just wrapped up a headlining tour with—the Stones opening for them—back in the UK. Phil, with his knack for being in the right place at the right time, found his way onto the Beatles’ first flight to America, Pan Am 101, and did his best to convince his new friend John that not all Americans were gun-crazed lunatics.

But Phil was himself a gun-crazed American. A couple years earlier, back in Philly after the Bandstand taping, Phil hit a public bathroom in the bus terminal. He was still in his stage duds looking very much out of place while relieving himself into one of those long, low, trough-like public urinals. From behind him, four street toughs bellowed out insults.

“Nice jacket,” Tough No. 1 muttered.

“What are you, some type of Cowboy Shrimp?” Tough No. 2 asked. The rest laughed.

Phil, still facing the urinal, his penis in hand, turned his head over his right shoulder to assess just how deep the shit that he was about to be in was.

“Got something to say, Cowboy Shrimp?”

Phil said nothing. Just turned his head back to the wall. His urine reversed its course back up into his bladder. Phil was frozen with fear.

“I’m talking to you, Cowboy Shrimp. Don’t ignore me!”

Phil kept quiet and tried to casually zip himself up. When he was done he turned around, kept his head down, and tried to briskly walk by them. Tough No. 1 threw his beefy shoulder into Phil, nearly knocking him off his feet and into Tough No. 2.

Tough No. 2: “You trying to start something, Cowboy Shrimp?”

Phil’s eyes darted toward the exit door. He made a hasty break for it but it was no use. The four toughs were on him immediately. They threw him to the ground and laid a beating on him he’d never forget. Phil’s anger at the situation was so intense he was nearly immune to the physical pain of the beating: the aching ribs from their kicks, the splintering headache from the round of punches his head endured. He made the decision right then and there: Never again would he go anywhere without protection.

They called it a “Peacemaker” but Phil never knew why. It was a violent instrument, the .45 Colt, a single-action revolver originally designed for standard military service back in the nineteenth century. The Peacemaker would come to be known as the “gun that won the West,” but to Phil Spector, it just looked cool. Like something the Lone Ranger would use. It was Phil’s first gun. He took it with him everywhere.

He gave John a look. “Hey, John, get a load of this.” Phil, now in the seat on the Boeing next to John, hunched over and reached into his carry-on, pulling up by the walnut grip his fully loaded, blued .45 Colt. He kept himself hunched over with his hand still holding the gun in the bag, just high enough to give his favorite Beatle a real glimpse at his added security.

“Fuck, Phil. See, all you Americans are crazy.”

“Nah, just careful.”

John slid easily into his well-rehearsed John Wayne impersonation and replied back to Phil in his deepest Duke baritone, “Now you put that away before little Ringo sees it and gets even more excited.”

Phil put the gun back into his bag and got up to pace again, but it wouldn’t be the last time Phil would flash his steel to a musician.

Leonard Cohen, Dee Dee Ramone, and once again John Lennon would all—in later years—claim that Spector pulled his gun on them. But their stories were child’s play compared to the tales of horror later told by the women in Phil Spector’s life.

Phil Spector showing John Lennon his gun, on the Beatles’ first flight to America.

“Listen to that! The Righteous Brothers!!! ‘You Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’.’ Hear that? Hear that voice? Listen to how big it is. Listen to how up front it is in the mix. Wait for it…Wait! There. The strings in the back. They’re there but they don’t take away from Bill’s voice. You know why? Because Bill could lay it on. THICK. And because Bobby wasn’t piping along with him and stepping on the vocal. Bobby was the sidecar. Bill was the tumbler. Rollin’ and tumblin’, baby. Listen to his voice effortlessly roll over the mix. Not even that orchestral percussion could step on it. Bill Medley had it. I had to sideline Bobby Hatfield. Bobby never forgave me. The song made him very rich, but still I’m the bad guy. What did he care, anyway? I made him more money with that song than he’d ever make in his life, and you know why? Because it didn’t need a tenor. It wasn’t a duet. It needed that big baritone that Bill had and that Bobby didn’t. That deep, lonesome voice that sounds like it’s whispering to you on a long, quiet drive; that is anchored by deep, swirling, emotional turmoil that the orchestra behind it is stewing up. IT WASN’T A FUCKING DUET, BOBBY! I’M SORRY! Now take your check and go to the bank!”

Phil Spector was on a rant. His little voice echoed through the vast corridors of his 8,600-square-foot residence, a dwelling with the appointed name of the Pyrenees Castle, overlooking the working-class town of Alhambra, California, like a monster in waiting. The sixty-nine-year-old producer was roaming through the enormous dwelling, alone save for servants tucked away for the night. Phil was keeping company with the dead, talking aloud to the ghost of his old friend, John Lennon. He knew Lennon was there with him as he spoke glowingly about their mutual childhood obsession, the King.

“Elvis’s version wasn’t bad but it wasn’t as good, either. Elvis had that voice, too, John. You knew it. Well, I’m telling you, I KNOW it! Such a voice. He was a great singer. You have no idea how great he really was. I can’t tell you why he was so great, but he was. He was sensational. He could do anything with that voice. I would have loved to have recorded him but the Colonel never would have allowed it. You know, ask some people who knew him, they’ll tell you, when Elvis went in a room with Colonel Parker he was one way, when he came out he was another. The Colonel hypnotized him. That’s the truth, too, I can tell you six or seven people who believe it who are not jive-ass people. I mean, he actually changed. You’d talk to Elvis and he’d be, ‘Yes, yes, yes!’ and then he’d go into that room with the Colonel and when he’d come out he’d be all, ‘No, no, no.’ Now, nobody can con you like that.

“Except the press, John. When the institutions line up against you, they can finish you. The LA County District Attorney’s office; they haven’t convicted anyone since Manson. Not O.J. Not Robert Blake. They’re gunning for me. You know what I’m talking about, right? Because you had it worse off. You had Nixon coming at you. Pissed off that he wasn’t a Kennedy and pissed off that you weren’t an American. Cons. All of them. Nixon, the Kennedys, the institutions, the authorities, and the press. Especially the press! They’re conning the public now. Telling ’em I killed that girl. Bullshit!”

Spittle was gathering at the corners of Phil’s mouth. He sipped his crème de menthe from a chalice and sat down at the white piano, an exact replica of the one he’d recorded John’s “Imagine” on. He plunked a few notes randomly and softly mumbled out a few words from “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’”:

It makes me just feel like cryin’

Cause baby, something beautiful’s dying.

The emotion of the lyrics was too much. He stood up and began pacing again to collect himself, turning his attention again to John.

“John, let me show you something. Look at my hands. I’m an old man. I couldn’t have done it. That girl. Special? No, she wasn’t special. There are thousands like her in LA. She could have been anybody. She was anybody. And what a mouth on her. She was drunk and loud and yeah, she wanted a ride home. Brought a bottle of tequila along with her. Then she wants to see the castle. It’d been a long night, but what do I do? I say, ‘Yeah, come see the castle,’ sure. And I thought I could score a piece of ass like I hadn’t in a while, not that I didn’t have opportunities.”

Phil fell into the plush of one of his many armchairs. Sat and sunk his small, slippered feet into the shag of the burgundy carpet. He poured out more of the syrupy green liqueur, picked up a framed photograph of Lennon, and raised his chalice to toast him.

“To you, my friend.” He sipped and breathed out slowly, loosening the stiffness in his neck.

“You want the truth, John? We get here, me and this girl, and I think, ‘Let’s take things to the next level, baby.’ Did we? Wouldn’t you like to know, John, you horny fuck. Maybe we did, maybe we didn’t. I’ll leave it at that. Anyway, then she’s checking out all of my stuff. My records. My carousel horse. My Lawrence of Arabia digs. Wandering around from room to room. Maybe she gets into my gun room? Maybe she reaches into her purse? All I know is suddenly she’s blown her fucking head off, right in my house. BOOM! In my castle. Right in that chair. She had no fucking right.”

Phil’s head felt light. He set the photo down where he could see it and placed his fingers at his temples, resting his elbows on the desk. The chair where it happened, a Louis XIV pushed up against the mirrored wall, had been replaced with a new one, covered in ivory damask. Clean. Like nothing happened.

Phil continued. He couldn’t help himself. John was a captive audience. “Blood? Sure, there was blood, John. You of all people know about blood. And so I get a little woozy over seeing her like that and go outside and call to my driver. THEY say I said, ‘I think I just killed somebody.’ C’mon…

“‘What, boss?’ My driver wants to know. I tell him, ‘I think I HAVE TO CALL somebody.’ Which I have to repeat three fucking times. Good guy, Adriano, but pretty much zero Inglés. So I yell, ‘I think I have to CALL SOMEBODY!’ And I go back inside, close the door, draw the drapes. I put some records on and wait. It’s maybe four, five in the morning. The sky is getting light when the cops get here. They’re waiting out there for a while and who the fuck knows why? Did they think they’d intimidate me? And then, BAM, they’re in here and they throw me to the ground, John. They break my septum. Would you look at my fucking septum? And I tell them I didn’t kill this stupid bitch and they must think I’m resisting because they Taser the fuck out of me. I pass out. Look at me. I weigh 130 pounds. Do I look like someone who has to be Tasered, and by a dozen giant cops, no less?”

Phil paced about, patted his hand against his wig, a mod cut, combed forward, the color of a new penny.

“Marta? Estas en la cocina? Mi amor? Por favor, tráeme otra botella, for fuck’s sake. I know you love me, baby. Everybody loves me. They want to be me but they lack courage. I can be anything I want. A fucking UN translator. Marta, dónde estás? I know Spanish. I love the Latin beat. I understand the Latin beat. Where the fuck is Marta?”

Phil shuffled over to the piano. Sat down. Exhausted. Distracted. He rubbed the two cigarette burns that he’d imagined Lennon had made with a pair of forgotten Gitanes. Removed his wire-framed, lavender-tinted glasses. Pinched the bridge of his nose. Looked down at the keys, a row of perfect pearly ivory. Teeth. Her top front teeth had been blown clear out of her head. Her face caved in. Phil caved into himself with shame.

“Let me ask you something, John? Why would I shoot her? Why would I, Philip Harvey Spector, shoot that girl? I had no motive. I…Had…No…Motive.

“Even your guy had a motive. That fat Chapman fuck. He thought you were a sellout, and you know what? He was right! And Kennedy’s guys, they had motive, too. But me? No motive. Sin motivo!”

Ronnie Spector driving around town with a dummy version of her jealous, possessive, psychotic husband, Phil.

But Phil Spector did have a motive. Fear. Fear of being left alone. Everyone he loved, it seemed, eventually left him.

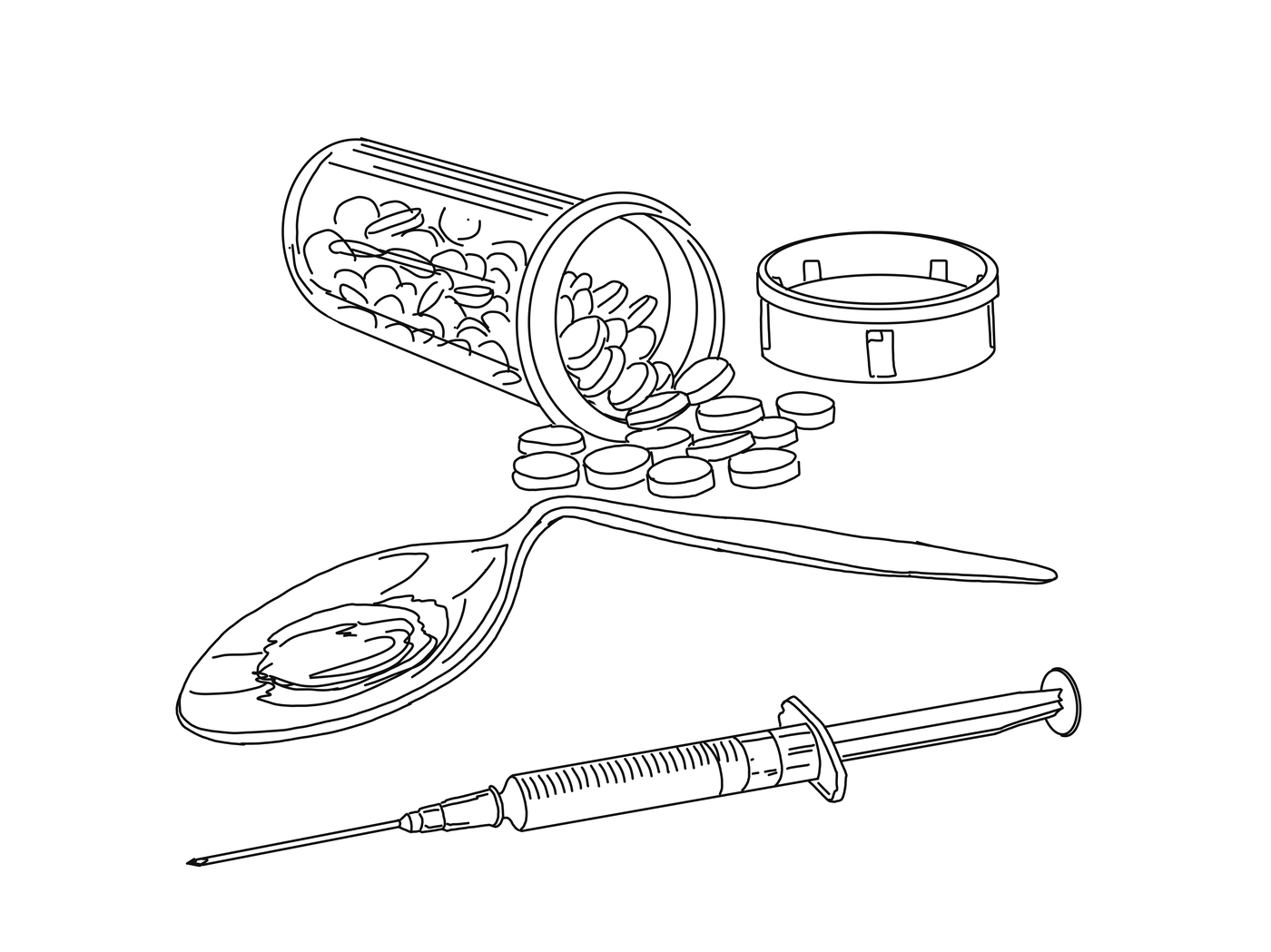

First, his good friend Lenny Bruce left him. Dead. Overdosed at forty.

Then there was Ronnie. That one hurt really bad. He fell in love with her while her star was in ascent. She was just in high school when Phil produced her singing “Be My Baby.” Phil didn’t need convincing. He was ready and willing to accept the invitation of the song’s title. That voice: unabashed New York City, baby. And those hips. Ronnie was perfect for Phil, but there was the problem of one Mrs. Annette Spector, Phil’s wife, a singer whom he had also produced in a group called the Spectors Three, which were basically a way less successful version of the Teddy Bears. But Ronnie wasn’t Annette. Ronnie was special. And worth the headache of busting up his marriage for. Phil threw himself into making Ronnie a star. He took her nickname, “Ronnie,” and turned it into a group name: the Ronettes. He threw her sister and her cousin up onstage next to her so it actually looked like a group. Voila. Write a hit. Record the hit. Release the hit. Again, voila. Star. Next? Marry her so she can’t up and leave you. So that’s what Phil did. He and Ronnie hitched up in 1968, the year after he had divorced Annette. Phil was quick to assert control in his second marriage, just like in the recording studio. The next year, the couple adopted a son—which Phil insisted Ronnie pretend she had given birth to. In Phil’s estimation, it was more of a sign of success to be biological parents, so they sent out birth announcements, inferring that Ronnie had given birth. Unlike Phil’s controlling nature in the studio, his controlling nature in the marriage did not yield successful results. Phil kept Ronnie locked up in their mansion for months at a time, refusing to let her out of his sight. When he did allow her to leave—for a maximum of twenty minutes at a time—he made her drive around with a life-sized dummy of Phil, complete with his signature cigarette hanging from his lips. Ronnie found an escape via alcohol, but where most habitual alcohol abuse can be a false escape, for Ronnie it was real: Phil put her in a sanitarium after every time she got drunk, which to her was a newfound freedom. She would drink to the depths of drunkenness every other month just to gain extended stays outside of the mansion. One time when Phil came to the sanitarium to collect Ronnie, she told him she wanted a divorce. He persuaded her to reconsider with a surprise gift: a pair of six-year-old twin boys he had adopted. No way was she going to leave him after that kind of pressure, he figured. Just six months later, when Ronnie could no longer take the psychological torture, she escaped barefoot and broke with her mother, under the ruse of “going for a walk” after Phil had shown her mom the coffin he kept in his basement. The one he said her daughter would end up in if she ever tried leaving.

And then there was John Lennon. He left Phil too. But that was different. A gun-crazed lunatic took him away, despite Phil’s early assurances to the contrary.

And those weren’t the only ones who tried leaving Phil Spector. Phil thought about them all, sitting in court on trial for the murder of Lana Clarkson. They brought up Ronnie, sure, but now they were laying it on thick for the jury. Trotting out testimony after testimony from every other wide-eyed cocktail waitress and rock ’n’ roll wannabe who’d crossed paths with Phil in the last twenty years.

First there was the photographer, Stephanie Jennings, who testified that after the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductions in New York back in 1994, Phil, who had a suite down the hall from her at the Carlyle Hotel, rang her up in her room and asked her to join him. She refused. Phil insisted. She was adamant. A few minutes later, Phil was outside her room with a gun and a chair. He wedged the chair against her hotel room doorknob, effectively locking her in and repeatedly yelled to her, “You ain’t going nowhere.” Stephanie called 911 and the cops came. Phil talked his way out of it and the incident was squashed.

Then there was the cocktail waitress, Melissa Grosvenor, who went back to Phil’s castle with him after a Beverly Hills dinner. When she later told him she wanted to go home, Phil pulled out his gun, held it hard against her temple, and said, “If you try to leave I’m going to kill you.” She did as she was told and stayed put. The next morning she split. Never to return to Phil despite his constant phone calls. When she failed to call him back, Phil left a message telling her, “I’ve got machine guns and I know where you live.”

Phil Spector was mad. A genius, yes, but mad. The prosecution said so as they deftly strung together a narrative depicting a brilliant mind who had a penchant for violence and a strong dislike for women who tried leaving him. The narrative culminated with the murder of Lana Clarkson, a talented B-movie actress turned cocktail waitress who’d gone home with Phil Spector one night. She died in Phil’s foyer, with her leopard print purse on her shoulder, where she’d been sitting in his Louis XIV chair just moments before her death in the familiar position of someone waiting to leave. The jury wasn’t entirely buying it. They weren’t convinced one way or another. Phil’s high-priced defense team succeeded in planting reasonable doubt in the minds of some of the jurors, resulting in a mistrial. But when he was tried again, Phil would be convicted. Nineteen years to life.

Behind bars, Phil kept company with his ghosts. Sometimes Lenny visited but mostly John. John was loyal like that.

“Look, John. I’m gonna tell you something. She kissed that fucking gun like she was in love with it. I have no idea why. How would I know? I’d only met her that night and I felt kind of sorry for her, but she had a sense of humor and I thought what the hell, John, we all gotta laugh, right?

“But was it worth it? Hell no. She died, John. AT MY HOUSE! She got blood everywhere. Blood on my favorite white coat. John, it was a fucking mess. Then it’s four, five months for the coroner to decide it’s a homicide? So they charge me. Then they send me to jail because this bitch blows herself away in my house?

“There was no case, John. I’m telling you. It was a suicide. Probably an accidental fucking suicide. Maybe an on-fucking-purpose suicide. But a goddamn suicide nonetheless.

“The jury, that first time. Couldn’t come to a consensus. Deadlocked. Mistrial. Then the next jury comes back guilty. You know why? The press! Robert Fucking Blake. FUCKING O. J. SIMPSON, JOHN! They needed their celebrity conviction. Me. I’m him. That’s who. Not some other guy. But really, that original jury had it on the first take. No one gets it on the first take. Not even you. Not even Elvis. But I gotta hand it to them. They got it. You know why? Because it wasn’t a homicide. It was just some depressed washed-up actress, fucked up on Vicodin, drunk, swinging around a bottle of Cuervo, who somehow gets my gun. A gun that turns out to be from Texas. I don’t know how, John, okay? Look, she kissed the gun. She was making a kind of joke about it, like she was giving it fucking head or something and she accidentally fired it. There’s no way I could have fired that gun. Look at that. Look at my hands shake! I can’t even hold my fucking dick, let alone a gun. I wouldn’t have put the gun in her mouth. I didn’t want her gone, John.

“I wanted her to stay. I never want them to leave. But they all leave! All of them. Lenny, you, Ronnie…all of them. My old man, even. That hump couldn’t stick around at least until I was out of short pants? No, he has to suck down on a gas hose. The pain is so bad? Being a father? Being a husband? Being a man? He can’t take it so he takes it out on the arches and just up and leaves. Kills himself. John…John? Where did you go, don’t leave, John. Come back. JOHN. Listen. The guards let me have this little record player. I’ve got some Elvis records we can listen to. John…John! Don’t leave!”